Abstract

Medulloblastoma (MB) is the most common malignant brain tumor of children. To identify the genetic alterations in this tumor type, we searched for copy number alterations using high density microarrays and sequenced all known protein-coding genes and miRNA genes using Sanger sequencing in a set of 22 MBs. We found that, on average, each tumor had 11 gene alterations, 5 to 10-fold fewer than in the adult solid tumors that have been sequenced to date. In addition to alterations in the Hedgehog and Wnt pathways, our analysis led to the discovery of genes not previously known to be altered in MBs. Most notably, inactivating mutations of the histone-lysine N-methyltransferase genes MLL2 or MLL3 were identified in 16% of MB patients. These results demonstrate key differences between the genetic landscapes of adult and childhood cancers, highlight dysregulation of developmental pathways as an important mechanism underlying MBs, and identify a role for a specific type of histone methylation in human tumorigenesis.

MBs originate in the cerebellum, have a propensity to disseminate throughout the central nervous system, and are diagnosed in approximately 1 in 200,000 children less than 15 years old each year (1). Although aggressive multimodal therapy has improved the prognosis for children with MB, a significant proportion of patients are currently incurable (2). Moreover, survivors often suffer significant treatment-related morbidities, including neurocognitive deficits related to radiation therapy. New insights into the pathogenesis of these tumors are therefore sorely needed. Gene-based research has identified two subgroups of MBs, one associated with mutated genes within the Hedgehog pathway and the other associated with altered Wnt pathway genes (3, 4). Amplifications of MYC and the transcription factor OTX2 (5–7), mutations in TP53 (8), and a number of chromosomal alterations have also been identified in MBs. These discoveries have helped define the pathogenesis of MB and have improved our ability to identify patients who might benefit from therapies targeting these pathways. However, most MB patients do not have alterations in these genes and the compendium of genetic alterations causing MB is unknown.

The determination of the human genome sequence and improvements in sequencing and bioinformatic technologies have recently permitted genome-wide analyses of human cancers. To date, the sequences of all protein-encoding genes have been reported in over eighty human cancers (9–20), representing a variety of adult tumors. In this study, we provide a comprehensive sequence analysis of a solid tumor of childhood. Our data point to a major genetic difference between adult and childhood solid tumors and provide new information to guide further research on this disease.

Sequencing Strategy

In the first stage of our analysis, called the Discovery Screen,457,814 primers (table S1) were used to amplify and sequence 225,752 protein coding exons, adjacent intronic splice donor and acceptor sites, and miRNA genes in 22 pediatric MB samples (17 samples extracted directly from primary tumors, 4 samples passaged in nude mice as xenografts, and 1 cell line; tables S2 and S3). Seven metastatic MBs were selected for inclusion in the Discovery Screen to ensure that high-stage tumors were well-represented in the study. One matched normal blood sample was sequenced as a control. These analyses corresponded to 50,191 transcripts representing at least 21,039 protein encoding genes present in the Ensembl, CCDS and Ref Seq databases and 715 microRNA genes from the miR Base database. A total of 404,438 primers were described in our previous publications and an additional 53,376 primers were newly designed to amplify technically-challenging genomic regions, miRNAs, or newly discovered Ensembl genes (table S1). The data were assembled for each amplified region and evaluated using stringent quality control criteria, resulting in the successful amplification and sequencing of 96%of targeted amplicons and 95% of targeted bases in the 22 tumors. A total of 735 Mb of tumor sequence data were generated in this manner.

Following automated and manual curation of the sequence traces, regions containing potential sequence alterations (single base mutations and small insertions and deletions) not present in the reference genome or single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) databases were re-amplified in both the tumor and matched normal tissue DNA and analyzed either through sequencing by synthesis on an Illumina GAII instrument or by conventional Sanger sequencing (21). This process allowed us to confirm the presence of the mutation in the tumor sample and determine whether the alteration was somatic (i.e. tumor-specific). Additionally, mutations identified in the four xenograft samples were confirmed to be present in the corresponding primary tumors.

Analysis of sequence and copy number alterations

A total of 225 somatic mutations were identified in this manner (Table 1 and table S4). Of these, 199 (88%) were point mutations and the remainder were small insertions, duplications or deletions, ranging from 1 to 48b pin length. Of the point mutations, 148(74%) were predicted to result in non-synonymous changes, 42(21%) were predicted to be synonymous, and 9(5%) were located at canonical splice site residues that were likely to alter normal splicing. 36 of the 225(16%) somatic mutations were predicted to prematurely truncate the encoded protein, either through newly generated nonsense mutations or through insertions, duplications or deletions leading to a change in reading frame. The mutation spectrum observed for MB was similar to those seen in pancreatic, colorectal, glial and other malignancies (22), with 5′-CG to 5′-TA transitions observed more commonly than other substitutions (Table 1). Such transitions are generally associated with endogenous processes, such as deamination of 5-methylcytosine residues, rather than exposure to exogenous carcinogens (23).

Table 1.

Summary of somatic sequence mutations in five tumor types.

| Medulloblastoma* | Pancreas# | Glioblastoma† | Colorectal‡ | Breast‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of samples analyzed | 22 | 24 | 21 | 11 | 11 |

| Number of mutated genes | 218 | 1007 | 685 | 769 | 1026 |

| Number of non-silent mutations | 183 | 1163 | 748 | 849 | 1112 |

| Missense§ | 130 (71.0) | 974 (83.7) | 622 (83.2) | 722 (85) | 909 (81.7) |

| Nonsense§ | 18 (9.8) | 60 (5.2) | 43 (5.7) | 48 (5.7) | 64 (5.8) |

| Insertion§ | 5 (2.7) | 4 (0.3) | 3 (0.4) | 4 (0.5) | 5 (0.4) |

| Deletion§ | 14 (7.7) | 43 (3.7) | 46 (6.1) | 27 (3.2) | 78 (7.0) |

| Duplication§ | 7 (3.8) | 31 (2.7) | 7 (0.9) | 18 (2.1) | 3 (0.3) |

| Splice site or UTR§ | 9 (4.9) | 51 (4.4) | 27 (3.6) | 30 (3.5) | 53 (4.8) |

| Average number of non-silent mutations per sample | 8 | 48 | 36 | 77 | 101 |

| Observed/expected number of nonsense alterations^ | 2.48 | 1.18 | 1.00 | 1.25 | 1.37 |

| Total number of substitutions** | 199 | 1486 | 937 | 893 | 1157 |

| Substitutions at C:G base pairs | |||||

| C:G to T:A†† | 109 (54.8) | 798 (53.8) | 601 (64.1) | 534 (59.8) | 422 (36.5) |

| C:G to G:C†† | 12 (6.0) | 142 (9.6) | 67 (7.2) | 61 (6.8) | 325 (28.1) |

| C:G to A:T†† | 41 (20.6) | 246 (16.6) | 114 (12.1) | 130 (14.6) | 175 (15.1) |

| Substitutions at T:A base pairs | |||||

| T:A to C:G†† | 19 (9.5) | 142 (9.6) | 87 (9.3) | 69 (7.7) | 102 (8.8) |

| T:A to G:C†† | 14 (7.0) | 79 (5.3) | 24 (2.6) | 59 (6.6) | 57 (4.9) |

| T:A to A:T†† | 4 (2.0) | 77 (5.2) | 44 (4.7) | 40 (4.5) | 76 (6.6) |

| Substitutions at specific dinucleotides | |||||

| 5′-CpG-3′†† | 85 (42.7) | 563 (37.9) | 404 (43.1) | 427 (47.8) | 195 (16.9) |

| 5′-TpC-3′†† | 14 (7.0) | 218 (14.7) | 102 (10.9) | 99 (11.1) | 395 (34.1) |

Based on 22 tumors analyzed in the current study

Based on 24 tumors analyzed in (18).

Based on 21 nonhypermutable tumors analyzed in (19).

Numbers in parentheses refer to percentage of total non-silent mutations.

Ratio of observed to expected nonsense alterations is dependent on mutation spectra in each tumor type (21).

Includes synonymous as well as nonsynonymous point mutations identified in the indicated study.

Numbers in parentheses refer to percentage of total substitutions

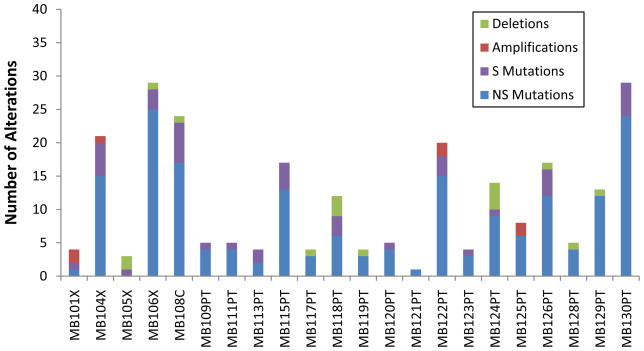

The distribution of somatic mutations among the 22 MBs is illustrated in Fig. 1. Two key differences were observed in this cancer as compared to the typical adult solid tumor. First, the average number of non-silent (NS) somatic mutations (non-synonymous mis sense, nonsense, indels, or splice site alterations) per MB patient was only 8.3, which is 5 to 10-fold less than the average number of alterations detected in the previously studied solid tumor types (Table 1). Second, the proportion of nonsense mutations was over two fold higher than expected given the mutation spectra observed in this tumor type (P<1 × 10−4, χ-squared test), and the relative fraction of nonsense, insertion, and duplication alterations was higher in MBs than in any of the adult solid tumors analyzed (Table 1)(21).

Fig. 1. Number of genetic alterations detected through sequencing and copy number analyses in each of the 22 cancers.

NS, non-silent mutations (including non-synonymous alterations, insertions, duplications, deletions, and splice site changes); S, silent mutations; Deletions, gene-containing regions absent in tumor samples; Amplifications, gene-containing regions focally amplified at levels > 10 copies per nucleus (21).

We evaluated copy number alterations using Illumina SNP arrays containing ~1 million probes in a set of 23 MBs, including all Discovery Screen samples. Using stringent criteria for focal amplifications and homozygous deletions, we identified 78 and 125 of these alterations, respectively, in these tumors (tables S5 and S6)(21). High level amplifications indicate an activated oncogene within the affected region, whereas homozygous deletions may signal inactivation of a tumor suppressor gene. The total number of copy number changes affecting coding genes in each tumor is plotted in Fig. 1. Similar to the point mutation data, we found considerably fewer amplifications (an average of 0.4 per tumor) and homozygous deletions (an average of 0.8 per tumor) affecting coding genes than observed in adult solid tumors (which average 1.6 amplifications and 1.9 homozygous deletions)(18, 19, 24).

We next evaluated a subset of the mutated genes in an additional 66 primary MBs, including both pediatric and adult tumors (tables S2 and S3). This “Prevalence Screen” comprised sequence analysis of the coding exons of all genes that were either found to be mutated twice or more in the Discovery Screen or were mutated once in the Discovery Screen and had previously been reported to be mutated in other tumor types. Non-silent somatic mutations were identified in 7 of these 15 genes (table S4). In the Prevalence Screen, the non-silent mutation frequency was calculated to be 9.5 mutations per Mb, far higher than the rate found in the Discovery Screen (0.24 mutations per Mb; P<0.001, Fisher’s exact test). The ratio of NS to S mutations in the Prevalence Screen was 24 to 1, which is over 4-fold higher than the 4.4 to 1 ratio determined in the Discovery Screen (P<0.01, Fisher’s exact test). In addition, 23 of the 50 Prevalence Screen mutations (46%) were nonsense alterations or insertions or deletions that were expected to truncate the encoded protein. These data suggest that the genes selected for the Prevalence Screen were enriched for functionally important genes.

Frequent mutation of MLL2 and MLL3 in MB

Somatic mutations in tumor DNA can either provide a selective advantage to the tumor cell (driver mutations) or have no net effect on tumor growth (passenger mutations). A variety of methods are available to help distinguish whether a specific gene or individual mutation is likely to be a driver. At the gene level, the “passenger probability” score corresponds to a metric reflecting the frequency of mutations, including point mutations, indels, amplifications, and homozygous deletions, normalized for sequence context as well nucleotide composition and length of the gene. The lower the passenger probability score, the less likely it is that mutations in the specific gene represent passengers. Passenger probability scores of the candidate cancer genes (CAN-genes) identified in MB are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Medulloblastoma CAN-genes*

| Gene | Number of Mutations | Number of Amplifications | Number of Deletions | Passenger Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTCH1 | 22/88 | 0/23 | 0/23 | <0.001 |

| MLL2 | 12/88 | 0/23 | 0/23 | <0.001 |

| CTNNB1 | 11/88 | 0/23 | 0/23 | <0.001 |

| TP53 | 6/88 | 0/23 | 0/23 | <0.001 |

| MYC | 0/88 | 3/23 | 0/23 | <0.001 |

| PTEN | 3/88 | 0/23 | 0/23 | 0.008 |

| OTX2 | 0/88 | 2/23 | 0/23 | 0.015 |

| SMARCA4 | 3/88 | 0/23 | 0/23 | 0.104 |

| MLL3 | 3/88 | 0/23 | 0/23 | 0.104 |

CAN-genes were defined as those having at least two non-silent alterations in the samples analyzed. Passenger probabilities were calculated as described in (21). The denominators refer to the number of tumors evaluated: 88 tumors were sequenced for mutations and 23 tumors were analyzed for copy number alterations.

At the individual mutation level, the CHASM score is a metric reflecting the likelihood that a missense mutation alters the normal function of the respective protein and provides a selective advantage to the tumor cell (25). The CHASM score is based on 73 biochemical features, including conservation of the wild-type amino acid and the mutation’s predicted effects on secondary structure. The CHASM score for each mutation observed in this study and the associated P-value are listed in table S4. Nonsense mutations, as well as small insertions or deletions that disrupt the reading frame, are likely to disrupt function and are assigned a score of 0.001 in this table. Approximately 36%of the evaluated mutations in MB were predicted to disrupt gene function using this approach, a proportion higher than observed in the adult tumor types analyzed to date (21).

Finally, we evaluated the Discovery Screen mutational data (including both sequence and copy number alterations) at a higher “gene-set” level. There is now abundant evidence that alterations of driver genes can be productively organized according to the biochemical pathways and biological processes through which they act. The number of gene-sets that define these pathways and processes is much less than the number of genes and can provide clarity to lists of genes identified through mutational analyses. In the current study, we used a recently described approach that scores each gene-set at the patient rather than the gene level and is more powerful than conventional gene-oriented approaches (21, 26). The most statistically significant pathways and biologic processes highlighted by this gene-set analysis are depicted in table S7. Of these, two-the Hedgehog and Wnt signaling pathways -have been previously shown to play a critical role in MB development. In the Hedgehog pathway, PTCH1 was mutated in 15 of 88(17%) tumors, and in the Wnt pathway, CTNNB1 was mutated in 11 of 88(13%) tumors (table S4).

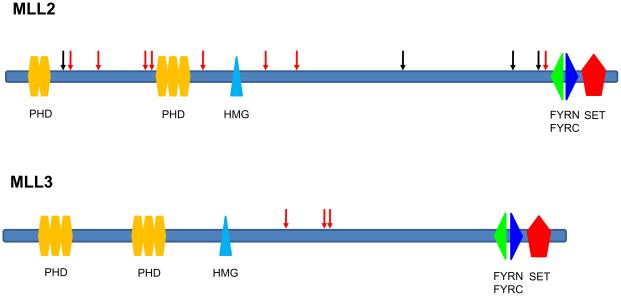

Remarkably, however, the pathways most highly enriched for genetic alterations had not previously been implicated in MB. These involved genes responsible for chromatin remodeling and transcriptional regulation, particularly the histone-lysine N-methyltransferase MLL2. Eighteen of the 88(20%) tumors harbored a mutation in a gene within these pathways or in a related gene member: the histone-lysine-N methyltransferases MLL2 (mutated in 12 tumors) and MLL3 (3 tumors); the SWI/SNF-related matrix-associated actin-dependent regulator of chromatin members SMARCA4 (3 tumors) and ARID1A (1 tumor); and the histone lysine demethylase KDM6B (1 tumor). The mutations in these genes could be clearly distinguished from passenger alterations. In MLL2, for example, 8 of the 12 mutations (67%) were predicted to truncate the encoded proteins as a result of nonsense mutations, out-of-frame indels, or splice site mutations. In contrast, only 32 of the 222 mutations (14%) not affecting core genes of the Hedgehog, Wnt, or MLL2-related pathways (PTCH1, CTNNB1, MLL2, MLL3, SMARCA4, ARID1A, and KDM6B) resulted in predicted protein truncations (p<0.001, Fisher’s exact test). The probability that by chance alone 11 of the 15 mutations in the two histone methyltransferase genes would cause truncations is very small (p<0.001, binomial test). All truncating mutations in MLL2 and MLL3 were predicted to result in protein products lacking the key methyltransferase domain (Fig. 2). These data not only provide strong evidence that these pathways are important to MBs, but they also show that MLL2 and MLL3 are, on the basis of genetic criteria, tumor suppressor genes that are inactivated by mutation.

Fig. 2. Somatic mutations in MLL2 and MLL3 genes.

Nonsense mutations and out of frame insertions and deletions are indicated as red arrows, while missense mutations are indicated as black arrows. Domains indicated include PHD, plant homeo domain finger, HMG, high mobility group box, FYRN, FY-rich N-terminal domain, FYRC, FY-rich C-terminal domain, SET, Su (var)3–9 Enhancer-of-zeste Trithorax methyltransferase domain.

Discussion

These data provide a comprehensive view of a solid tumor arising in children. The most impressive difference between this tumor type and those affecting adults is the number of genetic alterations observed. This result could not have been predicted on the basis of prior evidence (27). In fact, at the karyotypic level, the incidence of chromosomal changes in MBs is often described as high as that in adult solid tumors (reviewed in (27)).

What does the smaller number of mutations reveal about the tumorigenesis of MBs? Most mutations observed in adult tumors are predicted to be passenger alterations (19). Passenger mutations provide an evolutionary clock that precisely records the number of divisions that a cell has undergone during both normal development and tumor progression. Therefore, the cell division number is linearly related to the number of passenger mutations detected in a tumor (28). This concept is consistent with the positive correlation we identified between increasing patient age and the number of mutations found in their MBs. This relationship was observed for both the mutations detected in the exomes of the Discovery Screen tumors (r= 0.73, p<0.01) as well as the number of alterations observed in the subset of 15 genes analyzed in the Discovery and Prevalence Screen samples (r=0.32, p<0.01)(tables S8 and S9). Even if we assume that all but one of the mutations in each MB is a passenger, the number of passenger mutations in MBs is still substantially smaller than the number of passenger mutations in adult solid tumors (16–19), implying that a smaller number of cell divisions is required to reach clinically-detectable tumor size in MBs. These data therefore suggest that fewer driver mutations are required for MB tumorigenesis and that driver mutations in MB confer a greater selective advantage than those of adult solid tumors.

Previously, most insights into the molecular basis of MB emerged from the study of hereditary tumor syndromes (27), including Gorlin Syndrome, caused by germline mutations of PTCH1, Turcot Syndrome, caused by germline mutations of APC, and the Li-Fraumeni Syndrome, caused by germline mutations of TP53. In our study, we found both PTCH1 and TP53 to be somatically mutated in MBs (Tables 2 and S4), at frequencies similar to those observed in earlier studies. We also identified amplifications of MYC and OTX2, both previously implicated in MB (5–7).

The ability to investigate the sequence of all coding genes in MBs has also revealed mutated genes not previously implicated in MBs (table S4). Among these, MLL2 and MLL3 were of greatest interest, as the frequency of inactivating mutations unequivocally establishes the mas MB tumor suppressor genes. This genetic evidence is consistent with functional studies showing that knock-out of murine MLL3 results in ureteral epithelial cancers (29). These genes are large and have been reported in the COSMIC database to be altered in occasional cancers, but not at a sufficiently high frequency to distinguish them from passenger alterations (and with no evidence of a high fraction of inactivating mutations)(30). Interestingly, inactivating germline mutations of MLL2 have recently been identified as a cause of Kabuki syndrome, a multiple malformation disorder without known cancer predisposition (31).

The general role of genes controlling histone methylation has become increasingly recognized as a common feature of human cancers. For example, inactivating mutations of the histone H3K27 demethylase gene UTX have been observed in multiple myelomas, esophageal cancers and renal cell cancers (32). In addition, a small fraction of renal cell cancers contain mutations in the histone methyltransferase gene SETD2 and the histone demethylase gene JARID1C (33), and the histone methyltransferase gene EZH2 has been found to be mutated in non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (34). Most recently, frequent mutations of the chromatin remodeling gene ARID1A have been discovered in ovarian clear cell carcinomas (20, 35); of note, one ARID1A mutation was discovered in our MB patients (table S4). A link between histone methylation genes (although not MLL2 or MLL3) and MB has also previously been hypothesized based on the observation that copy number alterations affecting chromosomal regions containing histone methyltransferases or demethylases occur in a subset of MBs (36).

The mechanism (s) through which MLL genes contribute to tumorigenesis are not known but some clues can be gleaned from the literature. The MLL family of histone H3K4 trimethylases includes seven genes (MLL1, MLL2, MLL3, MLL4, MLL5, SET1A and SET1B) (37). MLL-family genes have been shown to regulate HOX gene expression (38, 39), and an attractive possibility is that they normally down-regulate OTX2, an MB oncogene (6, 7, 40). Another possibility is suggested by the observation that β-catenin brings MLL complexes to the enhancers of genes regulating the Wnt pathway, thereby activating their expression (41). A third possibility is that MLL family genes are important for transcriptional regulation of normal brain development and differentiation (42) and their disruption may lead to aberrant proliferation of precursor cells.

The identification of MLL2 and MLL3 as frequently-inactivated MB genes supports the concept that MB is fundamentally characterized by dysregulation of core developmental pathways (43). Although alterations of classic cancer genes (e.g. TP53, MYC, and PTEN) were also identified in these childhood tumors, our sequence analysis demonstrated that mutations of genes involved in normal developmental processes, such as MLL family genes and Hedgehog and Wnt pathway genes, were much more frequent. The fact that a relatively small number of somatic mutations is sufficient for MB pathogenesis as compared to adult solid tumors provides further evidence that the temporally-restricted subversion of normal cerebellar development is critical in the development of these tumors. This is consistent with the observation that the incidence of MB decreases significantly after childhood, with the tumors becoming quite rare after the age of 40 years (1). It will be interesting to determine if genetic alterations in developmental pathways are a key feature of all childhood malignancies.

The development of an improved classification system for MB that could be used to guide targeted risk-adapted therapy to patients is a primary goal of current MB research. The designation of specific histologic subtypes of MB has proven to be of some prognostic value. For example, large-cell/anaplastic MBs, which are aggressive tumors often associated with MYC amplification, carry a relatively poor prognosis (44), while desmoplastic MBs, which frequently have alterations of PTCH1 or other Hedgehog pathway genes (4), are more easily treatable. However, molecular studies have revealed that these histologic subtypes are biologically heterogeneous (3); in addition, most MBs are of the classic subtype and do not have defining molecular alterations. Our results add an additional layer of complexity to these classifications. Although activation of the Wnt and Hedgehog pathways are generally considered to define two MB subtypes (3), our data revealed that these groups overlap, as two adult MBs were found to contain mutations of both PTCH1 and CTNNB1 (tables S2 and S4). Similarly, MLL2/MLL3 mutations do not appear exclusive to any known subset of MBs: mutations were identified in both pediatric and adult MBs, and were found in all histologic subtypes (although they were most common in large-cell/anaplastic MBs)(Tables 3, S9, S10). In addition, the frequency of MLL2/MLL3 mutations was observed to be similar in PTCH1 or CTNNB1 mutated MBs (4/24, 17%) as compared to MBs without mutations in PTCH1 or CTNNB1 (10/64, 16%). Further studies of these genes in larger number of MBs that have been analyzed for pathologic subtypes will be needed to clarify the molecular classification of this tumor.

Table 3.

Characteristics of medulloblastomas with mutations in MLL2-related genes*

| Tumor ID | MLL2 mutation | MLL3 mutation | SMARCA4 mutation | ARID1A mutation | KDM6B mutation | Patient age (years) | MB subtype | PTCH1 mutation | CTNNB1 mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MB104X | Nonsense | Nonsense | 8 | Classic | |||||

| MB108C | Missense | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| MB115PT | Missense | 5 | Classic | ||||||

| MB118PT | Frameshift | 9 | Classic | Yes | |||||

| MB124PT | Frameshift | 9 | Large cell/anaplastic | ||||||

| MB126PT | Missense | 11 | Large cell/anaplastic | ||||||

| MB127PT | Frameshift | 10 | Unknown | ||||||

| MB129PT | Nonsense | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| MB130PT | Frameshift | Unknown | Unknown | Yes | |||||

| MB135PT | Frameshift | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| MB205PT | Nonsense | 11 | Classic | ||||||

| MB216PT | Missense | 33 | Large cell/anaplastic | ||||||

| MB231PT | Missense | 18 | Classic | Yes | |||||

| MB245PT | Frameshift | 9 | Classic | ||||||

| MB246PT | Missense | Missense | 7 | Classic | Yes | ||||

| MB249PT | Nonsense | 10 | Classic | Yes | |||||

| MB251PT | Frameshift | 26 | Large cell/anaplastic | Yes | |||||

| MB253PT | Nonsense | 32 | Nodular/desmoplastic |

All genes reported in the table were determined to be wildtype unless otherwise indicated.

We conclude that each MB is driven by a small number of driver mutations, and in our cohort, the gene-set most highly enriched for alterations included MLL2. However, there are several limitations to our study. Though in a few cases we have identified two or three bona fide cancer genes that are mutated in individual MBs, other cases show no mutations of any known cancer gene, and only one alteration of any gene (Fig 1. and table S4). Several explanations for the relative absence of genetic alterations in occasional MBs can be offered. First, despite the use of classic Sanger sequencing, a small fraction of the exome cannot be examined, either because of a very high GC content or of homology to highly related genes. Second, it is possible that mutations in the non-coding regions of the genome could occur and these would not be detected. Third, copy-neutral genetic translocations, not evaluated in our study, could be present in those tumors with very few point mutations, amplifications, or homozygous deletions. Fourth, it is possible that low copy number gains or loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH) of specific regions containing histone-modifying genes could mimic the intragenic mutations that we observed (36). Finally, it is possible that heritable epigenetic alterations are responsible for initiating some MBs. The last explanation, involving covalent changes in chromatin proteins and DNA, is intriguing given the new data on MLL2 in this tumor type. It should thus be informative to characterize the methylation status of histones and DNA in MBs with and without MLL2/MLL3 gene alterations, as well as to determine the expression changes resulting from these gene mutations. These data highlight the important connection between genetic alterations in the cancer genome and epigenetic pathways and provide potentially new avenues for research and disease management in MB patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Janine Ptak, Natalie Silliman, Lisa Dobbyn, Melissa Whalen for technical assistance with sequencing analyses, and Melissa Ehinger, Diane Satterfield, Eric Lipp, David Lister and Margaret J. Dougherty for help with sample preparation and data collection. This project has been funded in part with Federal Funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. This work was supported by The Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research, Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation, the American Brain Tumor Association, the Brain Tumor Research Fund at Johns Hopkins, the Hoglund Foundation, the Ready or Not Foundation, Children’s Brain Tumor Foundation, The Pediatric Brain Tumor Foundation Institute, AACR Stand Up To Cancer-Dream Team Translational Cancer Research Grant, Johns Hopkins Sommer Scholar Program, NIH grants CA121113, CA096832, CA057345, CA118822, CA135877and GM074906-01A1/B7BSCW, NSF grant DBI 0845275, and DOD NDSEG Fellowship 32 CFR 168a. DWP is a Graham Cancer Research Scholar at Texas Children’s Cancer Center. Under licensing agreements between the Johns Hopkins University and Beckman Coulter, B.V., K.W.K., and V.E.V., are entitled to a share of royalties received by the university on sales of products related to research described in this paper. N.P., B.V., K.W.K. and V.E.V are a co-founders of Inostics and Personal Genome Diagnostics and are members of their Scientific Advisory Boards. N.P., B.V., K.W.K. and V.E.V. own Inostics and Personal Genome Diagnostics stock, which is subject to certain restrictions under University policy.

Footnotes

The terms of these arrangements are managed by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict-of-interest policies.

References and Notes

- 1.Giangaspero F, et al. In: WHO Classification of the Central Nervous System. Louis HODN, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, editors. WHO Press; Lyon: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polkinghorn WR, Tarbell NJ. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007 May;4:295. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Northcott PA, et al. J Clin Oncol. Sep 7; doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.4324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson MC, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Apr 20;24:1924. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.4974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bigner SH, et al. Cancer Res. 1990 Apr 15;50:2347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boon K, Eberhart CG, Riggi GJ. Cancer Res. 2005 Feb 1;65:703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di C, et al. Cancer Res. 2005 Feb 1;65:919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saylors RL, 3rd , et al. Cancer Res. 1991 Sep 1;51:4721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding L, et al. Nature. 2010 Apr 15;464:999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee W, et al. Nature. 2010 May 27;465:473. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mardis ER, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009 Sep 10;361:1058. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pleasance ED, et al. Nature. 2009 Jan 14;463:191. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pleasance ED, et al. Nature. 2010 Jan 14;463:184. doi: 10.1038/nature08629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah SP, et al. Nature. 2009 Oct 8;461:809. doi: 10.1038/nature08489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ley TJ, et al. Nature. 2008 Nov 6;456:66. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sjoblom T, et al. Science. 2006 Oct 13;314:268. doi: 10.1126/science.1133427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood LD, et al. Science. 2007 Nov 16;318:1108. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones S, et al. Science. 2008 Sep 26;321:1801. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parsons DW, et al. Science. 2008 Sep 26;321:1807. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones S, et al. Science. 2010 Oct 8;330:228. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 22.Greenman C, et al. Nature. 2007 Mar 8;446:153. doi: 10.1038/nature05610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soussi T, Beroud C. Hum Mutat. 2003 Mar;21:192. doi: 10.1002/humu.10189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leary RJ, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Oct 21;105:16224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808041105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carter H, et al. Cancer Res. 2009 Aug 15;69:6660. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boca SM, Velculescu VE, Vogelstein B, Parmigiani G. Genome Biology. 2010 doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-11-r112. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Northcott PA, Rutka JT, Taylor MD. Neurosurg Focus. 2010 Jan;28:E6. doi: 10.3171/2009.10.FOCUS09218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beerenwinkel N, et al. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007 Nov;3:e225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee J, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 May 26;106:8513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902873106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forbes SA, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010 Jan;38:D652. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ng SB, et al. Nat Genet. 2010 Sep;42:790. doi: 10.1038/ng.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Haaften G, et al. Nat Genet. 2009 May;41:521. doi: 10.1038/ng.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dalgliesh GL, et al. Nature. 2010 Jan 21;463:360. doi: 10.1038/nature08672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morin RD, et al. Nat Genet. 2010 Feb;42:181. doi: 10.1038/ng.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiegand KC, et al. N Engl J Med. 2010 Oct 14;363:1532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Northcott PA, et al. Nat Genet. 2009 Apr;41:465. doi: 10.1038/ng.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vermeulen M, Timmers HTM. Epigenomics. 2010 June;2:395. doi: 10.2217/epi.10.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ansari KI, Mandal SS. FEBS J. 2010 Apr;277:1790. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agger K, et al. Nature. 2007 Oct 11;449:731. doi: 10.1038/nature06145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adamson DC, et al. Cancer Res. 2010 Jan 1;70:181. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sierra J, Yoshida T, Joazeiro CA, Jones KA. Genes Dev. 2006 Mar 1;20:586. doi: 10.1101/gad.1385806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lim DA, et al. Nature. 2009 Mar 26;458:529. doi: 10.1038/nature07726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilbertson RJ, Ellison DW. Ann Rev Pathol. 2008;3:341. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eberhart CG, et al. Cancer. 2002 Jan 15;94:552. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.