Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to assess patient interest in intensive meditation training for chronic symptoms.

Design and setting

This was a cross-sectional anonymous survey among six chronic disease clinics in Baltimore including Chronic Kidney Disease, Crohn's Disease, Headache, Renal Transplant Recipients, General Rheumatology, and lupus clinic.

Subjects

Subjects were 1119 consecutive patients registering for their appointments at these clinics.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures were 6-month pain, global symptomatology, four-item perceived stress scale, use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies, and attitudes toward use of meditation for managing symptoms. We then gave a scripted description of an intensive, 10-day meditation training retreat. Patient interest in attending such a retreat was assessed.

Results

Seventy-seven percent (77%) of patients approached completed the survey. Fifty-three percent (53%) of patients reported moderate to severe pain over the past 6 months. Eighty percent (80%) reported use of some CAM therapy in the past. Thirty-five percent (35%) thought that learning meditation would improve their health, and 49% thought it would reduce stress. Overall, 39% reported interest in attending the intensive 10-day meditation retreat. Among those reporting moderate to severe pain or stress, the percentages were higher (48% and 59%). In a univariate analysis, higher education, nonworking/disabled status, female gender, higher stress, higher pain, higher symptomatology, and any CAM use were all associated with a greater odds of being moderately to very interested in an intensive 10-day meditation retreat. A multivariate model that included prior use of CAM therapies as predictors of interest in the program fit the data significantly better than a model not including CAM therapies (p = 0.0013).

Conclusions

Over 50% of patients followed in chronic disease clinics complain of moderate to severe pain. Patients with persistent pain or stress are more likely to be interested in intensive meditation.

Introduction

For many medical conditions, the use of medications and allopathic therapies often has limited effectiveness in alleviating patient symptoms, such as pain. Chronic pain affects over 50 million Americans, and those 50 years and older are twice as likely to be diagnosed with it.1 As a consequence of the challenges of managing chronic pain, many patients seek, in addition to their physician's treatment, complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies to further reduce their pain.2,3

Use of CAM therapies has been increasing over the past several years.4–6 The reasons for this are not entirely clear, but appear to include various factors such as a desire among a subset of the population to use “natural” therapies, improve health and well-being, gain greater control over health, increased awareness of CAM therapies, lack of adequate insurance to pay for allopathic care, and persistent pain and symptoms that are refractory to conventional allopathic care.2–5,7–9

While some CAM therapies have been in use for centuries, the benefits of such therapies are not clearly understood in Western medical practice as research in this area is still nascent. To date, a number of studies have shown that yoga, massage, and acupuncture have shown an ability to mitigate pain or nonpain symptoms.10–15 However, the effect sizes of these benefits have been modest, and none appear to eradicate pain completely.

Within the Western scientific community, even less is understood about meditation.16,17 A recent comprehensive review concluded that due to a paucity of well-designed studies, firm conclusions on the effects of meditation could not be assessed.16 Intensive meditation practices have also not been assessed in rigorous randomized designs.

There are many types of meditation, differentiated by the type of mental activity that is practiced and how central religion is to the technique. The most common forms of meditation studied in the West have involved relatively little individual effort and training.18,19 However, in some traditional Eastern approaches, meditation requires significant investment of time and training to gain proficiency in the practice. To this end, individuals often prioritize the practice over other responsibilities to dedicate themselves to the theory and applications of meditation. Clinical trials to date have not assessed the effectiveness of these intensive meditation approaches.

Vipassana meditation is a secular form of “mindfulness meditation” in which the student learns to observe him/herself systematically and dispassionately.20,21 To learn the technique, strong emphasis is placed on practice, and students are typically asked to spend 10 days initially at a retreat learning and practicing. Given the promising results of “low dose” meditation techniques toward treating pain, we sought to assess the interest in and feasibility of conducting a study of Vipassana meditation among patients suffering from chronic symptoms.22–26

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Six (6) chronic disease clinics in eight sites were identified at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine or Johns Hopkins–affiliated sites, and their directors were approached for permission to conduct the survey. In five of the clinics, all consecutive patients were given the survey upon registering for their appointment. In the general rheumatology clinic, the surveys were placed in a visible box as they entered with a sign asking them to take a survey and return it to the front desk. At all other clinic sites, the surveys were handed to the patients as they registered for their appointment. The Crohn's clinic was limited to Crohn's patients who were receiving infliximab infusions.

Measures

The survey was anonymous and collected the following information: average pain over the past 6 months using the Numerical Rating Scale-11 (NRS-11),27 Global Symptomatology, the four-item Perceived Stress Scale,28 use of various CAM therapies listed in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) 2007 supplement, attitudes toward meditation, number of medications, and chronicity of disease. We assessed Global Symptomatology by asking patients “Despite treatment for your health problems, how symptomatic are you in terms of your sense of not being well, discomfort, fatigue, or any other symptoms?” Responses were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all symptomatic” to “extremely symptomatic.” After assessing these variables, we briefly described the 10-day meditation training in the following way: “Learning meditation can require a significant amount of personal training to be effective. Some people have more time than others to devote to this type of personal project. One type of training begins with a 10-day retreat that helps you get started. The retreat is about a 2-hour drive from Baltimore. During the retreat you would train for 10 hours each day. The first day begins with a seminar that introduces you to the concepts and technique of meditation. Then the group practices meditation (wearing comfortable clothes and seated in a comfortable position) in hour-long blocks while listening to prerecorded voice guidance. At the close of each day there is another seminar discussing the steps for how to train the next day. After the training, you could get together weekly with others to practice meditation for an hour or two. It does not involve or replace religion.” Participants were then asked how interested they would be in attending an intensive meditation retreat on a 4-point Likert scale (very interested to definitely not interested).

Moderate to severe pain was coded as those who reported 5 or more on the NRS-11. The Perceived Stress Scale adds up the responses from the four items and moderate to severe stress was categorized as 10 or more on the four-item Perceived Stress Scale (range 0–16). Outcomes were computed using simple proportions.

Data analysis

We used logistic regression to first identify demographic and self-reported health variables associated with interest in an intensive meditation retreat in a univariate analysis. An initial multivariate model was formed by stepwise addition of variables that were significant (p < 0.05) in a univariate model, keeping only those variables that were also significant in the multivariate model. A second multivariate model was assessed by adding all the CAM variables that had at least 10% or more prevalence of use in the dataset. This second model was compared to the first using a likelihood ratio test. The final multivariate logistic regression model included the following variables: education, working status, gender, stress, and 6-month pain. It also adjusted for the following CAM variables: Use of acupuncture, natural herbs, prayer, chiropractic, massage, special diet, vitamins, yoga, meditation, guided imagery, breathing techniques, and relaxation techniques.

The study received approval from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Results

Among 1119 surveys handed out, we had an overall 77% response rate, with greater than 90% response in all but one clinic (Table 1). Seventy-one percent (71%) of the respondents were women, 72% had completed at least some college, and 60% stated they had their condition for more than 5 years (Table 2).

Table 1.

Response Rates of Clinics

| Clinic | Actual completed | Total surveys distributed | Response rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic kidney disease | 74 | 76 | 0.97 |

| Crohn's | 58 | 63 | 0.92 |

| Headache | 337 | 360 | 0.94 |

| Renal transplant recipients | 136 | 151 | 0.90 |

| Rheumatology | 153 | 357 | 0.43 |

| Lupus | 107 | 112 | 0.96 |

| Total | 865 | 1119 | 0.77 |

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Percent |

|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD) | 47 (15) |

| Female | 71 |

| Some college or more | 72 |

| Had medical condition for more than 5 yrs | 60 |

| Ever used a CAM therapy | 80 |

| Taking 6+ medicines | 46 |

| No prior experience with meditation, yoga, or structured relaxation training | 54 |

| Mean pain severity (past 24 hrs, 0–10 scale) | 3.6 |

| Mean pain severity (past 6 months, 0–10 scale) | 4.7 |

| Mean perceived stress score (0–16)a | 5.7 |

0 represents lowest stress.

SD, standard deviation; CAM, complementary and alternative medicine.

Pain, symptoms, and stress

Overall, 88% of patients reported at least some pain over the past 6 months and 85% reported at least some global symptomatology. Fifty-three percent (53%) reported moderate to severe pain over the past 6 months and 56% reported moderate to severe symptoms. Lupus, rheumatology, and headache clinics had the highest proportion of patients reporting moderate to severe pain (range 42%–77%) as well as the highest proportion of patients reporting moderate to severe global symptoms (50%–70%).

Overall only 12% reported moderate to severe stress. Two percent (2%) of renal transplant recipients reported having moderate to severe stress, while 16% of headache patients and 18% of Crohn's infliximab patients reported moderate to severe stress.

Use of CAM

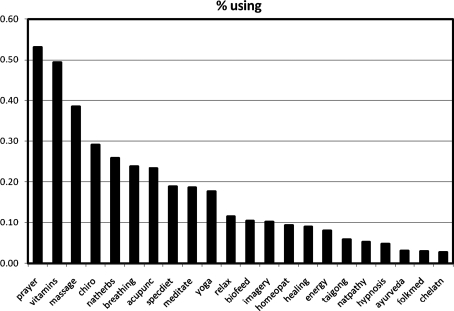

Among the 89% who answered the question, 80% reported using some type of CAM therapy in the past. The use of CAM ranged from 63% in chronic kidney disease to 88% in the lupus clinic. The most common CAM therapies employed were prayer (53%), vitamins (49%), and massage (39%) (Fig. 1). Nineteen percent (19%) stated they had meditated at some point. The use of all therapies was highly correlated; the pairwise correlations between each pair of therapies were highly significant (all p < 0.001).

FIG. 1.

Use of complementary and alternative medicine therapies.

Attitudes and interest in meditation

Overall, 35% of respondents thought that learning meditation would improve their health, and 49% thought it would reduce their stress. Forty-three percent (43%) were unsure of the effects of meditation on their health and 37% were unsure whether learning meditation would reduce their stress. After having had the intensive 10-day meditation retreat described to them, 39% reported being moderately to very interested in attending the retreat. Crohn's patients had the highest interest at 52%, then headache (45%), general rheumatology (39%), lupus (39%), renal transplant recipients (28%), and chronic kidney disease (11%). Among those reporting moderate to severe pain, symptoms, or stress, the percentages reporting interest in the retreat were high (48%, 49%, and 59%).

In a multivariate analysis, having at least some college education, being female, not working or being disabled, having higher stress, and having higher levels of 6-month pain were all associated with interest in attending the intensive training (Table 3). Higher quartiles of stress and 6-month pain had greater association with interest in attending intensive training as compared to the lowest quartile of those predictors when compared with a model excluding those variables using a likelihood ratio test (p < 0.001 and p = 0.001, respectively). There were no significant interactions between stress, pain, or gender.

Table 3.

Variables Associated with Interest in Intensive Meditation

| Variable | Univariate OR | Adjusted OR |

|---|---|---|

| Higher education | 2.7 (1.9–3.9) | 2.9 (1.9–4.3) |

| Nonworking/disabled status | 1.9 (1.3–2.7) | 1.7 (1.1–2.7) |

| Female gender | 2.0 (1.4–2.8) | 1.5 (1.0–2.2) |

| PSSa,b 2nd quartile | 1.7 (1.1–2.6) | 1.4 (0.9–2.3) |

| PSSa 3rd quartile | 3.5 (2.3–5.5) | 3.0 (1.8–4.8) |

| PSSa 4th quartile | 3.8 (2.4–6.0) | 2.3 (1.4–3.9) |

| 6-month paina,c 2nd quartile | 1.5 (1.0–2.3) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) |

| 6-month paina 3rd quartile | 2.5 (1.6–3.9) | 1.7 (1.0–2.7) |

| 6-month paina 4th quartile | 3.9 (2.5–5.9) | 2.4 (1.5–4.0) |

The 2nd, 3rd, and 4th quartile are each being compared to the lowest quartile.

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (0–16), 0 indicates lowest stress.

Six-month pain is on a 0–10 scale.

OR, odds ratio.

As univariate predictors, all CAM therapies other than folk medicine, chelation therapy, and t'ai chi/qigong were associated with an interest in attending the retreat. When comparing the overall model of the demographic predictors with CAM therapies compared to a model without CAM therapies using a likelihood ratio test, the model with CAM therapies was significantly more likely (p = 0.0013). Because CAM therapies are highly correlated, we have not interpreted the independent significance of each individual therapy.

Discussion

The results of this survey make four important points. First, persistent pain and symptoms are common among chronic disease populations who are receiving conventional care. Fifty-three percent (53%) had moderate to severe pain for the past 6 months and 56% complained of moderate to severe symptoms. Sixty percent (60%) of the sample had suffered from their condition for more than 5 years and appeared to have persistent symptoms despite the best efforts of their treating physicians. While each chronic disease population we surveyed has guidelines to direct treatment, there appears to be a ceiling on how effective the treatments are. Complicating this further is the fact that older individuals are more likely to be diagnosed with chronic pain, and emotions and psychology contribute heavily to the overall pain experience.1

Second, there was widespread use of CAM in this population, with 80% having used some form of CAM in the past. In line with other studies of CAM use, we also found that higher education and female gender were associated with greater interest in attending the meditation retreat.29 In another multicenter survey of 463 outpatients suffering from chronic pain, 52% reported use of CAM for relief of pain.2 The prevalence was even higher among an ambulatory internal medicine teaching clinic, in which 85% of patients reported using some form of CAM.7 The differences in prevalence of CAM use may in part be due to differences in the definition of CAM used. Prayer was considered a CAM therapy in the latter study. Irrespective of these differences, use of CAM was widespread, and is similar to the estimates we obtained in our survey. We also found that those who had higher stress or pain were more likely to be interested in attending the retreat. This is consistent with the hypothesis that patients are interested in alternative therapies partly to mitigate refractory pain.

Third, the potential intervention, for which we assessed interest, is quite demanding of one's time. Despite this, a large number of patients responded that they were interested in the 10-day meditation retreat. Thirty-nine percent (39%) of all patients reported that they were moderately to very interested in attending such an intensive intervention. Of these, 44% reported no experience with meditation, hypnosis, biofeedback, t'ai chi, qigong, imagery, relaxation techniques, or breathing techniques. Fourteen percent (14%) of those expressing interest reported having never used any CAM technique in the past. This indicates a significant openness to an intensive form of meditation.

Fourth, the data suggest that a fairly high percentage of the patients are desperate enough to want to invest a great deal of time and effort in their own recovery. This is a point worth emphasizing because it may have significance for many CAM approaches. Many patients value using less medication due to side-effects, desire to reduce their out-of-pocket expense on medication, desire more natural therapies, and desire self-empowering therapies.2–5,7–9 While we did not explicitly explore these issues in our survey, they may be an important undercurrent in the responses we received.

Strengths of this study include a large sample with a high response rate from a variety of chronic disease clinics and anonymous responses unlikely to have a response bias toward pleasing a physician. There are several limitations. Patients' responses to CAM are dependent on their knowledge of these therapies, which remains inconsistent in the West and may limit accuracy. For example, what is meditation may be perceived differently by different people. The cross-sectional nature of the data do not allow us to know whether people used CAM before their chronic disease was diagnosed or after. Finally, our description of the 10-day retreat was brief. While a more in-depth description of the retreat and explanation of the reasons for the intensity would take significantly longer, it may modify responses. The responses assume that the retreats would be available at convenient times throughout the year to accommodate individual schedules.

Conclusions

The high level of interest and openness to intensive meditation training is promising. Vipassana meditation is a standardized method of learning meditation, is accessible in many centers across the world, and provides an advanced environment for students to begin an explicit training of self-awareness.20 Students learn to objectively observe themselves, and take their observations to subconscious levels as they progress. The focus is on cultivating a deep level of awareness while developing an objective dissociation from the valence of an experience in order to observe and understand the experience. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and transcendental meditation both train students for no more than about 20–30 hours over a 2-month period. To understand the complex interactions between mind and body, studying higher doses of meditation may be useful in future meditation research. Ambulatory patients appear open to such a training possibility.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by T32 HL007180, 1KL2RR025006-01, and the Society of General Internal Medicine Founders Award.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Gatchel RJ. Peng YB. Peters ML, et al. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: Scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:581–624. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg EI. Genao I. Chen I, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use by primary care patients with chronic pain. Pain Med. 2008;9:1065–1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Astin JA. Why patients use alternative medicine: Results of a national study. JAMA. 1998;279:1548–1553. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes PM. Bloom B. Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2009:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolsko PM. Eisenberg DM. Davis RB, et al. Insurance coverage, medical conditions, and visits to alternative medicine providers: Results of a national survey. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:281–287. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenberg DM. Davis RB. Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: Results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–1575. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhee SM. Garg VK. Hershey CO. Use of complementary and alternative medicines by ambulatory patients. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1004–1009. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.9.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saydah SH. Eberhardt MS. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among adults with chronic diseases: United States 2002. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12:805–812. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bausell RB. Lee WL. Berman BM. Demographic and health-related correlates to visits to complementary and alternative medical providers. Med Care. 2001;39:190–196. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200102000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherman KJ. Cherkin DC. Erro J, et al. Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:849–856. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-12-200512200-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garfinkel MS. Singhal A. Katz WA, et al. Yoga-based intervention for carpal tunnel syndrome: A randomized trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1601–1603. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cherkin DC. Eisenberg D. Sherman KJ, et al. Randomized trial comparing traditional Chinese medical acupuncture, therapeutic massage, and self-care education for chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1081–1088. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.8.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walach H. Guthlin C. Konig M. Efficacy of massage therapy in chronic pain: A pragmatic randomized trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2003;9:837–846. doi: 10.1089/107555303771952181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vickers AJ. Rees RW. Zollman CE, et al. Acupuncture of chronic headache disorders in primary care: Randomised controlled trial and economic analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(iii):1–35. doi: 10.3310/hta8480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birch S. Hesselink JK. Jonkman FA, et al. Clinical research on acupuncture. Part 1. What have reviews of the efficacy and safety of acupuncture told us so far? J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10:468–480. doi: 10.1089/1075553041323894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ospina MB. Bond K. Karkhaneh M, et al. Meditation practices for health: State of the research. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2007;155:1–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ospina MB. Bond K. Karkhaneh M, et al. Clinical trials of meditation practices in health care: Characteristics and quality. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14:1199–1213. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Astin JA. Shapiro SL. Eisenberg DM. Forys KL. Mind–body medicine: State of the science, implications for practice. J Am Board Family Pract Am Board Family Pract. 2003;16:131–147. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrows KA. Jacobs BP. Mind–body medicine: An introduction and review of the literature. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:11–31. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(03)00069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vipassana. www.dhamma.org. [May 1;2009 ]. www.dhamma.org

- 21.Hart W. The Art of Living: Vipassana Meditation as Taught by S.N. Goenka. Igatpuri, India: Vipassana Research Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morone NE. Greco CM. Weiner DK. Mindfulness meditation for the treatment of chronic low back pain in older adults: A randomized controlled pilot study. Pain. 2008;134:310–319. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kingston J. Chadwick P. Meron D. Skinner TC. A pilot randomized control trial investigating the effect of mindfulness practice on pain tolerance, psychological well-being, and physiological activity. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62:297–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Astin JA. Berman BM. Bausell B, et al. The efficacy of mindfulness meditation plus Qigong movement therapy in the treatment of fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2257–2262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaplan KH. Goldenberg DL. Galvin-Nadeau M. The impact of a meditation-based stress reduction program on fibromyalgia. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1993;15:284–289. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(93)90020-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ludwig DS. Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness in medicine. JAMA. 2008;300:1350–1352. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hartrick CT. Kovan JP. Shapiro S. The numeric rating scale for clinical pain measurement: A ratio measure? Pain Pract. 2003;3:310–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-7085.2003.03034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen S. Kamarck T. Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tindle HA. Davis RB. Phillips RS. Eisenberg DM. Trends in use of complementary and alternative medicine by US adults: 1997–2002. Altern Ther Health Med. 2005;11:42–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]