Abstract

Background: This study explores effects of instrumental music on the hormonal system (as indicated by serum cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone), the immune system (as indicated by immunoglobulin A) and sedative drug requirements during surgery (elective total hip joint replacement under spinal anesthesia with light sedation). This is the first study investigating this issue with a double-blind design using instrumental music. Methodology/Principal Findings: Patients (n = 40) were randomly assigned either to a music group (listening to instrumental music), or to a control group (listening to a non-musical placebo stimulus). Both groups listened to the auditory stimulus about 2 h before, and during the entire intra-operative period (during the intra-operative light sedation, subjects were able to respond lethargically to verbal commands). Results indicate that, during surgery, patients of the music group had a lower propofol consumption, and lower cortisol levels, compared to the control group. Conclusion/Significance: Our data show that listening to music during surgery under regional anesthesia has effects on cortisol levels (reflecting stress-reducing effects) and reduces sedative requirements to reach light sedation.

Keywords: emotion, music, hormones, immunology, anesthesia, cortisol, IgA, ACTH

Introduction

Music is capable of evoking strong positive emotions, and of elevating the mood of individuals (reviewed in Juslin and Västfjäll, 2008; Koelsch, 2010; Koelsch et al., 2010). These effects can potentially be used in clinical settings, in which negative emotions such as pain and anxiety often reduce an individual's subjective well-being, and call for the application of anxiolytic, analgesic, and anesthetic drugs. Music has been reported to reduce stress before (e.g., Wang et al., 2002; Cooke et al., 2005; Bringman et al., 2009), during (e.g., Chan et al., 2003; Uedo et al., 2004; Bechtold et al., 2006; Rudin et al., 2007), and after (Cepeda et al., 2006) medical procedures including surgery, angiography, and colonoscopy. Correspondingly, five patient studies suggest that listening to music reduces cortisol levels before (Miluk-Kolasa et al., 1994; Leardi et al., 2007), during (Schneider et al., 2001; Uedo et al., 2004; Leardi et al., 2007), and after (Nilsson et al., 2005) such procedures. Related to the lower stress levels of patients listening to music, a number of studies reported that sedative requirements are reduced in patients undergoing surgery under regional anesthesia combined with sedation, both for midazolam (Lepage et al., 2001; Ganidagli et al., 2005; Harikumar et al., 2006) and propofol (Koch et al., 1998; Ayoub et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2005). Similar effects have been reported for (analgo-)sedated patients treated on intensive care units (Conrad et al., 2007). The stress- and pain-reducing effects of music are presumably due to its capability to engage perceptual, emotional, and cognitive processes (reviewed in Koelsch and Siebel, 2005; Koelsch, 2010) that (a) interfere with the perception of the noise of the operating theater, (b) consume attentional resources, and (c) evoke feelings of pleasure which interact with pain and unpleasant affects related to the surgical procedure.

However, despite their merits, previous studies on stress-reducing effects of music during surgical procedures were either not blinded (Miluk-Kolasa et al., 1994; Lepage et al., 2001; Schneider et al., 2001; Uedo et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2005; Leardi et al., 2007), or no control stimulus was used in the control group (hence control subjects were partly exposed to the potentially stressful theater noise; Miluk-Kolasa et al., 1994; Koch et al., 1998; Lepage et al., 2001; Schneider et al., 2001; Uedo et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2005; Conrad et al., 2007; Leardi et al., 2007), or different types of anesthesia were used (Leardi et al., 2007), or the musical stimulus contained lyrics (hence, effects could have been in part due to comforting effects of the lyrics; Miluk-Kolasa et al., 1994; Lepage et al., 2001; Schneider et al., 2001; Fukui and Yamashita, 2003; Ayoub et al., 2005; Ganidagli et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2005; Harikumar et al., 2006; Leardi et al., 2007). The present study takes these methodological issues into account, with the aim to further test possible beneficial effects of listening to music on perioperative stress levels, and on sedative drug requirements.

As physiological indices of subjective stress we measured cortisol levels, and levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH); these endocrinological measures reflect hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis activity and increase under physiological and psychological stress, although such stress is not the only antecedence for a rise of cortisol and ACTH levels (see, e.g., the circadian variation of these hormones; Dantzer et al., 2008). Cortisol (a corticosteroid hormone that is crucial for glucose metabolism, inflammation suppression, and stress adaptation) is the biochemical that has been investigated most frequently with regard to music (for a review see Quiroga Murcia et al., in press). Notably, out of numerous studies that investigated cortisol levels in response to music (Quiroga Murcia et al., in press), only eight studies used control group designs (VanderArk and Ely, 1992; Brownley et al., 1995; Möckel et al., 1995; McKinney et al., 1997a; Grape et al., 2003; West et al., 2004; Nater et al., 2006; LeRoux et al., 2007). Except one study (which did not observe effects of music listening on cortisol levels; see reference Nater et al., 2006), these studies showed cortisol reductions as an effect of listening to (pleasant) music with small (Cohen's d = 0.31 in the study by VanderArk and Ely, 1992) to medium effect sizes (Cohen's d = 0.62 in the study by McKinney et al., 1997a).

Fewer studies investigated effects of music listening on ACTH levels, with inconsistent results, namely increase (Gerra et al., 1998), decrease (Oyama et al., 1983), or no change (Evers and Suhr, 2000; Migneault et al., 2004; Conrad et al., 2007) of ACTH levels. Two of these studies (Evers and Suhr, 2000; Migneault et al., 2004) investigated effects of music listening on ACTH levels during intra-operative periods, and although these studies did not find changes of ACTH levels, we obtained ACTH values to investigate possible post-operative effects on this measure.

In addition to such hormonal effects, stress levels also affect immune system activity (Dantzer et al., 2008); one of these effects is a transient increase of immunoglobulin A (IgA, an immune-systemic antibody) in response to an increase in HPA-axis activity (Hucklebridge et al., 1998). Effects of music listening on serum IgA concentrations were so far only investigated under general anesthesia (Nilsson et al., 2005), and statistically not significant. Nevertheless, four non-clinical studies suggest effects of music listening on salivary IgA concentrations in awake, healthy individuals (McCraty et al., 1996; Charnetski et al., 1998; Hucklebridge et al., 2000; Kreutz et al., 2004). Therefore, a supplementary aim of the present study was to further investigate possible effects of music listening on serum IgA levels as one index of immune system activity.

The present investigation used a standardized, randomized, double-blinded design in which a music group was presented with instrumental music, whereas the control group was presented with a relaxing auditory control stimulus (the sound of braking waves; a control group was measured to control for placebo effects). We measured (a) cortisol and ACTH as indices of HPA-axis activity, (b) IgA as a marker of immunofunction, and (c) sedative drug requirements (as indexed by propofol consumption and target concentration). Measurements were obtained in both groups before, during, and after surgery under spinal anesthesia. We hypothesized that music listening would have stress-reducing effects, and that such effects would be reflected in lower HPA-axis activity (i.e., in lower cortisol and ACTH levels), as well as in a decrease of sedative requirements (i.e., in lower requirements of propofol to achieve the targeted level of sedation). Moreover, due to the relation between HPA-axis activity and immune system activity (Hucklebridge et al., 1998; Dantzer et al., 2008), we hypothesized that immunofunction (as indicated by IgA levels) would differ between the music and the control group.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Sixty-one patients were initially assessed for participation in the study. Eight patients did not meet the inclusion criteria and three declined to take part. Fifty participants were randomly assigned to a music group (n = 26) and a control group (n = 24). In 10 of these 50 participants (six participants from the music group and four participants from the control group), the experiment was aborted because of a deviation of >30 min from the time-line of the study protocol (see Figure 1). Finally, 20 individuals of each group were included in the study (music group: 13 females, age range 43–92 years, mean age 67 years; control group: 12 females, age range 51–83 years, mean age 65 years). Subjects were measured between February 2006 and April 2007 at the Clinic of the University of Leipzig. Both groups did not differ with regard to body weight, age, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scores (see Table 1A); ASA scores represent classifications of the state of health before surgery, an ASA score of 1 indicates that the patient is normal and healthy, a score of 3 indicates that the patient has severe systemic disease.

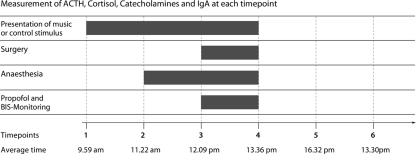

Figure 1.

Illustration of the six different time points (vertical lines) at which serum samples were obtained [the average time in the bottom row indicates the time of the day, averaged across all subjects; SEM was less than 25 min for each of the time points (TP)]. The auditory stimulation commenced at TP 1; TP 2 was immediately before applying spinal anesthesia, and TP 3 directly after skin incision. TP 4 was before skin closure; TP 5 was 3 h, and TP 6 was 24 h, after the end of surgery.

Table 1.

A: Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics. Means (with SD in parentheses) of weight (in years), age (in kg), and ASA scores, separately for each group. The outermost right column shows the T-values of independent-samples T-tests. B: Experimental variables related to the sedation of the subjects. Means (with SD in parentheses) of propofol consumption, propofol concentration, bispectral index (BIS), and BIS-value relative to propofol concentration (100–BIS-value/concentration), separately for each group.

| Control group | Music group | Test-statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A: DEMOGRAPHIC AND CLINICAL DATA | |||

| Weight (kg) | 81 (12.3) | 76 (14.5) | T(38) = 1.1 |

| Age (years) | 65 (9.2) | 67 (12.3) | T(38) = 0.6 |

| ASA | 2.2 (0.4) | 2.3 (0.5) | T(38) = 0.7 |

| B: EXPERIMENTAL VARIABLES | |||

| Propofol consumption (mg/kg/h) | 2.65 (0.59) | 2.22.94 | T(38) = 1.73, d = 0.56 |

| Propofol concentration (μg/ml) | 1.23 (0.27) | 1.05 (0.45) | T(38) = 1.57, d = 0.5 |

| BIS | 80 (4.0) | 77 (5.0) | T(38) = 1.62, d = 0.68 |

| 100–BIS/concentration | 16.9 (4.4) | 25.0 (12.2) | T(38) = 2.82, d = 0.91 |

The outermost right column shows the T-values of independent-samples T-tests, and values indicating Cohen's d.

Inclusion criteria were normal hearing (according to self report and the patient's file), ASA scores ranging from 1 to 3, and primary elective total hip joint replacement under spinal anesthesia. Exclusion criteria were presence of psychiatric disorder, professional musicianship, or intake of medication or drugs influencing the hypothalamo-hypohyseal or the sympathetic nervous system. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant at least 24 h before the commencement of the experiment; the study was approved by the local ethics committee of the University of Leipzig, and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Sample size was determined based on the intra-operative cortisol levels reported in (Leardi et al., 2007) which yield a minimum sample size of 15 per group (α level = 5%, β level = 50%). Participants were recruited and measured over a course of 14 months.

Stimuli

The musical stimulus was a selection of 15 joyful instrumental pieces from different styles and genres from the last four centuries [J. S. Bach BWV 1049/1, D. Brubeck Quartet “Take Five,” O'Stravaganza “Jig Della Inquietude,” Illapu “Las Obreras,” N. Paganini Op.6/3, J. Richman “Egyptian Reggae,” F. Kreisler “Liebesfreud,” Anonymous “Entree–Courante” (CD-ASIN B0000247QD), L. Armstrong “Indiana,” J. S. Bach BWV 1066/6, Irish Jig (anonymus), Shantel “Bucovina,” M. Bruch Op. 26/4]. Mean beats per minute (BMP) of pieces was 107 (range = 66–162). The stimuli had a total duration of 47 min, and had been rated as happy and pleasant in previous functional neuroimaging studies (Koelsch et al., 2006a, 2007). The control stimulus consisted of the noise of breaking sea waves (during the de-briefing, participants reported that they perceived this acoustic stimulus as relaxing and pleasant, see also below). Music and control stimuli were matched for duration and loudness.

Procedure

Participants did not receive any pre-medication during the day of measurement. Participants were only informed that they would receive relaxing acoustical stimulation before, during, and shortly after surgery, and that the purpose for this stimulation was the reduction of operation theater noise. They were not informed that there were two different groups of subjects (presented either with music, or with the control stimulus), and they were not informed about whether they would be presented with music or with sea waves noise (participants were enrolled, and assigned to their groups, by Julian Fuermetz and Maximilian Hohenadel).

Approximately 2 h before the surgery, participants filled out the German version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Laux et al., 1981; Spielberger et al., 1970, for a study reporting reduced pre-operative STAI scores in response to music see references, Wang et al., 2002; Bringman et al., 2009). Then, an intravenous catheter was placed, and the first blood sample was drawn (to determine the base level of all measured serum parameters). Subsequently, occlusive headphones were attached and connected to an MP3 player. To guarantee that the experimenter did not know to which type of stimulus the subject was listening, two (optically identical) MP3 players were used: one with music and one with the control stimulus. For each participant, one of the two players was randomly chosen by an experimenter (Julian Fuermetz). For this reason, and because participants did not know whether they belonged to the control group or the experimental group, this study had a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled experimental design.

The MP3 player was then started by the experimenter, the volume was identical for all subjects (and about 70 dB SPL, which was experienced as a pleasant volume by all participants), and the collection of stimuli was looped (i.e., the collection was automatically repeated after the last musical piece, or control stimulus). Because the operation had an average duration of about 1.5 h (and each stimulus selection had a duration of about 47 min), stimuli were on average presented twice during the experiment.

Blood samples were obtained during six different time points (see Figure 1 for illustration): The first time point was about 2 h before commencement of surgery (as described above), the second was immediately before applying spinal anesthesia, the third directly after skin incision (usually about 30 min after application of spinal anesthesia), the fourth before skin closure, the fifth 3 h, and the sixth 24 h after the end of surgery. Blood samples were cooled as soon as possible at 4°C, then centrifuged, and then stored at −80°C. Average time of commencement of the experiment was 9.59 am, the experiment commenced on average 23 min earlier in the music group than in the control group, but this difference between groups was statistically not significant (p > 0.6). At time point 6 (i.e., 24 h after surgery), participants’ contentment with the surgical procedure was assessed using a 10-point visual analog scale (VAS).

Anesthesia and intra-operative sedation

After local anesthesia of the skin spinal anesthesia had been established using a 25 gage whiteacre needle and bupivacaine 0.5% (15 mg) as anesthetic. The level of puncture was L3/4 or L2/3. Once spinal anesthesia had been established, all patients were sedated via target-controlled-infusion of propofol using a Diprifusor infusion system (Becton Dickinson Infusion Systems, Brezins, France) to establish bispectral index (BIS) values between 70 and 80 during surgery (the BIS is an electrophysiological measure used to monitor depth of anesthesia). This level of sedation is associated with a lethargic response of the patients to their name spoken in normal tone (Modified Observers Assessment of Alertness and Sedation level 4; see also reference Chernik et al., 1990). BIS-values were assessed using the BIS-Monitor A-2000 XP (BIS-algorithm 3.4, Aspect Medical Systems, Natick, MA, USA); BIS-values indicate the level of sedation, with decreasing BIS-values correlating with an increase of the level of sedation (i.e., higher BIS-values reflect a more awake state, and lower BIS-values reflect a sedated, or anesthetized state). To achieve the desired BIS-values, the target concentration was modified during surgery. Blood pressure and heart rate were monitored continuously throughout the surgery.

Statistics and data analysis

Laboratory analysis

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (Biomerica), Cortisol (IBL), and IgA (Bethyl) were determined using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). ACTH values of time points 4 and 5 could not be obtained for one subject of the control group. Although adrenaline and noradrenaline were also included in the trial protocol approved by the ethics committee, we did not further analyze the data of these parameters, because >20% of the blood samples could not be cooled within the first 60 s after obtaining the sample, leading to too many missing values at intra-operative time points.

Data analysis

Group differences in propofol consumption and propofol concentration were tested using one-tailed independent-samples t-tests. Two-tailed independent-samples t-tests were used to test intra-operative differences between groups in mean arterial blood pressure, heart rate, and fluid consumption (i.e., consumption of Deltajonin© and Voluven©). Patients’ satisfaction with the procedure was measured using a VAS and compared between groups using a two-tailed independent-samples t-test.

Adrenocorticotropic hormone, cortisol, and IgA levels were compared between groups, separately for the pre-operative period, the intra-operative period, and the post-operative period.

Pre-operative period (time point 1, before commencing the auditory stimulation)

Each of the parameters (cortisol, ACTH, IgA) was compared between groups using a two-tailed, two-samples t-test (to guarantee that concentrations of these parameters did not differ between groups at the beginning of the experiments).

Intra-operative period (time points 2–4)

For each of the parameters a repeated measures MANOVA was calculated with factors group (music, control group), and time point (time points 2, 3, and 4). MANOVAs (instead of separate two-samples t-tests for each time point) were conducted to protect against false-positive results and to increase the signal-to-noise ratio of the endocrinological data collected during the intra-operative period.

Post-operative period (time points 5 and 6)

For each of the parameters, a repeated measures ANOVA was calculated with factors group (music, control group), and time point (time points 5 and 6).

All statistical values obtained for any of the multivariate ANOVAs were Greenhouse–Geisser corrected. Cohen's d was calculated using means and SD, according to the guidelines provided by Thalheimer and Cook (2002), with d ≥ 0.40 and <0.75 indicating a medium effect size, and d ≥ 0.75 and <1.1 indicating a large effect size.

Results

Stai scores

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory scores (obtained before the commencement of the experiment) were virtually identical for both groups, with regards to both STAI-state scores (music group: M = 40, control group: M = 39; p > 0.77), and STAI-trait scores (music group: M = 35, control group: M = 35; p = 1.0).

Propofol

Patients of the music group tended to show a lower propofol consumption, and a lower propofol concentration compared to the control group (Table 1B; Figure 2). However, the mean BIS-value was nominally lower in the music group than in the control group (mean BIS-values of both groups were nevertheless within the range targeted by the anesthetist). Thus, subjects in the music group tended to be more deeply sedated despite nominally lower propofol concentrations. To test the difference in propofol consumption while controlling statistically for the levels of anesthesia (Leslie et al., 1995), we calculated for each subject a score of the BIS-value relative to the propofol concentration (100–BIS-value/concentration). These scores differed significantly between groups [T(38) = 2.82, p < 0.01, d = 0.91, indicating a large effect size].

Figure 2.

Average propofol consumption (left panel), target propofol concentration (middle panel), and propofol concentration relative to the BIS-value (100–BIS-value/concentration, right panel), separately for the two groups (control group, music group). Particularly in relation to the BIS-values, propofol requirement was significantly lower in the music compared to the control group. Error bars indicate SEM.

Cortisol

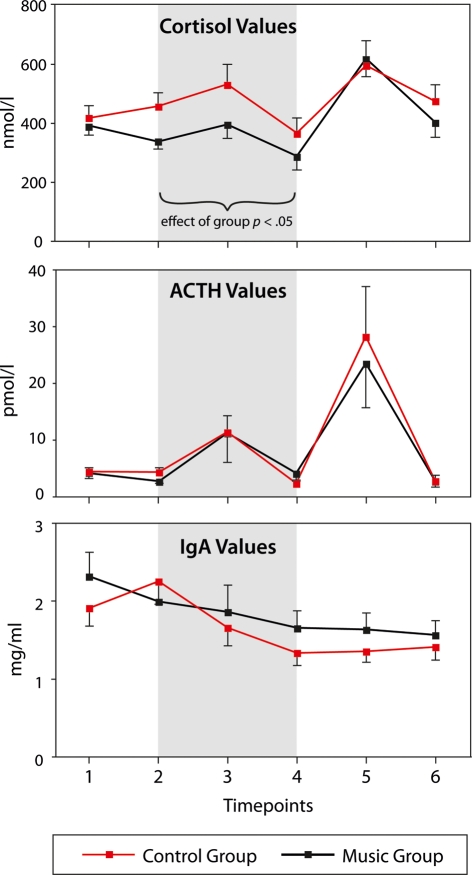

At time point 1 (i.e., before presenting the experimental stimulus), cortisol levels did not differ between groups (p = 0.61, see also Figure 3). At time points 2–4 (i.e., during the intra-operative period, see gray-shaded area in Figure 2), cortisol levels were lower in the music compared to the control group: A MANOVA (see Materials and Methods for details) on the cortisol values for the three inter-operative time points with factors group (music, control) and time point (three levels: spinal anesthesia, skin incision, skin closure) indicated an effect of group [F(1,38) = 4.3, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.1, observed power = 0.52), reflecting that cortisol levels were lower in the music than in the control group. Moreover, the MANOVA indicated an effect of time point [F(2,76) = 6.6, p = 0.002, η2 = 0.15, observed power = 0.9), reflecting that cortisol levels differed between the three time points. There was no two-way interaction (p > 0.7), indicating that the difference between groups persisted during the entire intra-operative period (see also Figure 3). At time points 5 and 6 (i.e., 3 and 2 h after the surgery), no differences in cortisol levels were observed between groups: A repeated measures ANOVA (see Materials and Methods for details) with factors group and time point (two levels: 3, 24 h after surgery) indicated an effect of time point [F(1,38) = 8.7, p = 0.005; reflecting that cortisol levels were higher 3 h than 24 h after the surgery, see also Figure 3), but no effect of group (p > 0.7).

Figure 3.

Cortisol, ACTH, and IgA values, separately for both groups (music group, control group) and the six different time points. Gray-shaded are indicate the intra-operative period. None of the parameters differed between groups at time point 1. During the intra-operative period, cortisol levels were lower in the music than in the control group. ACTH and IgA levels differed between time points, but not between groups. Error bars indicate SEM.

Adrenocorticotropic hormone

As cortisol levels, ACTH levels did not differ between groups at time point 1 (p > 0.9, see also Figure 3). During the intra-operative period, ACTH levels differed between time points, but not between groups. A MANOVA (see Materials and Methods for details) on the ACTH values for the three inter-operative time points with factors group and time point indicated an effect of time point [F(2,74) = 5.9, p < 0.02, η2 = 0.14, observed power = 0.7; note that the different degrees of freedom are due to missing ACTH values of time points 4 and 5 for one subject of the control group], but no effect of group (p > 0.95), and no two-way interaction (p > 0.6). Likewise, ACTH values differed between time points 5 and 6 (i.e., between the measurements obtained 3 and 24 h after the operation), but not between groups. A repeated measures ANOVA with factors group and time point (see Materials and Methods for details) indicated an effect of time point [F(1,38) = 15.9, p < 0.0001], but no effect of group (p > 0.7), and no two-way interaction (p > 0.7).

Immunoglobulin A

Similar to cortisol and ACTH levels, IgA levels did not significantly differ between groups at time point 1, again showing that groups did not differ from each other at baseline (music group: M = 2.34 mg/ml, SEM = 0.31; control group: M = 1.90 mg/ml, SEM = 0.24; p > 0.25, two-tailed independent-samples t-test). During the following time points, IgA levels generally decreased in both groups (except between time points 1 and 2, where IgA levels increased nominally in the control group, see Figure 3). A MANOVA (see Materials and Methods for details) for the three inter-operative time points with factors group and time point indicated an effect of time point [F(2,76) = 8.3, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.18, observed power = 0.95], but no effect of group (p > 0.7) and no two-way-interaction (p > 0.15).

During the post-operative period (time points 5 and 6, i.e., 3 and 24 h after the operation), no differences in IgA levels were observed between groups: A repeated measures ANOVA with factors group and time point (see Materials and Methods for details) indicated no main effects, neither of time point (p > 0.9), nor of group (p > 0.3).

Interestingly, the IgA levels declined over the course of the six time points: A linear regression with IgA levels as dependent, and time points as well as group as independent variables indicated a significant correlation between time points and IgA levels (adjusted R2 = 0.72; p < 0.001). This regression also indicated a tendency toward a difference in the regression models between groups (p = 0.082), reflecting that the decline in IgA levels was slightly less pronounced in the music compared to the control group.

Physiological parameters, fluid consumption, and patients’ satisfaction

No intra-operative differences between groups were measured in mean arterial blood pressure (music group: M = 86.1, SEM = 2.50; control group: M = 82.3, SEM = 2.27; p > 0.25) and heart rate (music group: M = 69.1, SEM = 2.17; control group: M = 70.4, SEM = 1.86; p > 0.6). Similarly, operative fluid consumption did not differ between groups, neither with regard to Deltajonin (p > 0.4) nor with regard to Voluven (p > 0.25).

When interviewed 24 h after the surgery, participants’ contentment with the surgical procedure (as assessed with a VAS, see Materials and Methods) did not differ between groups (music group: M = 8.7, SEM = 0.43; control group: M = 8.2, SEM = 0.46; p > 0.35). Moreover, when asked whether the auditory stimulus was perceived as pleasant or unpleasant (two-alternative forced choice) all participants from the control group, and 18 subjects from the music group, judged the experimental stimulus as pleasant.

Discussion

Both propofol consumption and propofol concentrations were about 15 percent lower in the music compared to the control group, even though BIS-values were nominally also lower in the music than in the control group (BIS-values reflect the depth of anesthesia, with lower values indicating deeper sedation levels). This demonstrates that listening to music reduces sedative requirements to reach light sedation under regional anesthesia.

In addition, cortisol levels were lower in the music group (compared to the control group) during the intra-operative period (i.e., during time points 2 to 4, see gray-shaded area in Figure 2). Because the day time of surgery was matched between music and control group, differences in circadian rhythm cannot account for the observed difference in intra-operative cortisol levels between groups (this is also reflected in virtually identical cortisol levels at time point 1, that is, before the onset of auditory stimulation). Besides serving normal metabolic and diurnal functions, the serum cortisol level also increases in response to psychological or physiological stress (e.g., Gerra et al., 2001). Notably, STAI scores were almost identical for both groups before the onset of the auditory stimulation, indicating that anxiety levels of the patients did not differ between groups before the commencement of the experiment (this is also corroborated by the cortisol levels which did not differ between groups at time point 1). Therefore, results indicate that the music had stress-reducing effects before and during surgery under regional anesthesia. This corroborates findings of previous studies investigating effects of music on salivary cortisol in clinical (Miluk-Kolasa et al., 1994; Schneider et al., 2001; Uedo et al., 2004; Nilsson et al., 2005; Leardi et al., 2007), and non-clinical samples (McCraty et al., 1996; Hucklebridge et al., 2000; Kreutz et al., 2004). Note that cortisol levels declined in the music group during the time period before application of anesthesia (whereas cortisol levels increased during this time period in the control group, see Figure 1), consistent with studies showing anxiety-reducing effects of music pre-surgically (Wang et al., 2002; Bringman et al., 2009). Thus, it appears that music prevented an anxiety-related increase in cortisol associated with the anticipation of the surgical procedure (and this difference in cortisol levels persisted the entire intra-operative period). Whether pre-operative music listening alone (i.e., without listening to music during the intra-operative period) is already sufficient to lead to similar cortisol reductions during surgery remains an open question.

Although cortisol plays an important role for adaptation to environmental challenges, patients usually report that they perceive the high pre- and intra-operative levels of stress, worry, and anxiety as markedly unpleasant. Hence, our observation of lower cortisol levels in the music group is taken here as beneficial effect, reflecting that participants were less stressed, anxious, and worried (see also, e.g., Uedo et al., 2004). The possible medical implications of different cortisol levels during surgery remain to be specified.

The present study considered a number of methodological issues necessary to pinpoint that the observed effects were due to a musical stimulus: (a) The present study used a randomized double-blinded experimental design, (b) only instrumental music was used (without lyrics, thus potential effects of lyrics could not contribute to the effects observed), (c) both the music group and the control group were presented with an auditory stimulus (thus, the theater noise was reduced in the same way in both groups), and (d) patients of both groups underwent the same surgical procedure. Thus, our data represent evidence for beneficial effects of music during surgery on stress levels (as indexed by the reduced cortisol levels in the music group) and on the requirements for anesthetic drugs (as indexed by the lower propofol consumption in the music group) in slightly sedated patients. This makes music an adjuvant treatment in a clinical setting, and supports previous findings suggesting that music listening can reduce cortisol levels (Miluk-Kolasa et al., 1994; Schneider et al., 2001; Uedo et al., 2004; Nilsson et al., 2005; Leardi et al., 2007) as well as sedative requirements (Koch et al., 1998; Lepage et al., 2001; Ayoub et al., 2005; Ganidagli et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2005; Harikumar et al., 2006).

The exact mechanisms underlying the observed effects of music listening on the stress levels remain to be specified. However, three mechanisms appear to be likely: First, up-regulation of activity within the mesolimbic dopaminergic system by the music (particularly by virtue of increased activity within the ventral tegmental area and the nucleus accumbens; Blood and Zatorre, 2001; Menon and Levitin, 2005; Koelsch et al., 2006a) with corresponding effects on the reactivity to stress and pain (Pani et al., 2000; Jääskeläinen et al., 2001). Second, down-regulation of activity of the central nucleus of the amygdala by the music (Blood and Zatorre, 2001; Koelsch et al., 2006a, 2008) with down-regulatory effects on (a) levels of fear and worries (LeDoux, 2000; Vollert et al., 2003), and (b) on activity of hypothalamic and brainstem nuclei involved in the generation of the endocrine (HPA-axis) and vegetative stress responses (Nieuwenhuys et al., 2007; such stress-related effects might also include modulations of beta-endorphin levels, McKinney et al., 1997b; Gerra et al., 1998; Vollert et al., 2003). Third, because musical information consumes cognitive (including attentional) resources (e.g., Koelsch and Siebel, 2005), participants of the music group might also have been more distracted from fearful and worrying thoughts, and from the perception of the surgical procedures (compared to participants of the control group).

No differences between groups were observed in the post-operative period (i.e., when participants did not listen to music anymore). Note that both cortisol and ACTH considerably increased after surgery (see time point 5 in Figure 3, this measurement was performed 3 h post-operatively), hence future studies should further investigate whether music listening during the post-operative period can reduce post-operative stress reactions, a suggestion that has already been made by Nilsson et al. (2005); they suggested that application of music might help to reduce cortisol and pain during the post-operative period. Furthermore, ACTH levels did not show differences between groups (despite differences in cortisol levels). This was perhaps due to the different pharmacokinetics of ACTH and cortisol, particularly burstlike secretion and shorter in vivo half-life of ACTH (<10 min, compared to ∼90 min for cortisol; Morgane and Panksepp, 1980; Keenan and Veldhuis, 2003), which introduced considerably larger ACTH variance (compared to cortisol). Future studies on effects of music on ACTH levels should take this factor into account when calculating the sample sizes.

Immunoglobulin A levels did not show significant group differences, but a significant reduction in both groups during the intra-operative period, and a further decline after surgery (as indicated by the regression analysis). The regression analysis also suggested a tendency toward a group difference in the decline of IgA levels (which appeared to be less pronounced in the music group). Future studies could test whether the latter finding can be replicated. Our findings are in accordance with results from a previous study (Nilsson et al., 2005) in which music listening did not affect serum IgA levels during operations under general anesthesia, but in which serum IgA concentrations declined significantly during the course of the operation. IgA increases in acute stress situations (Gerra et al., 2001) and is lower under chronic stress conditions (Phillips et al., 2006). So far, the immuno-kinetics of serum IgA during surgery is not well understood. Perhaps the long latency of IgA secretion, and the long half-life of IgA (5 days) makes effects of severe acute stressors on IgA levels difficult to investigate.

In the present study, effects were observed during regional anesthesia (and under light sedation), that is, in a condition in which participants were consciously perceiving the music. We have previously reported (Heinke et al., 2004; Heinke and Koelsch, 2005; Koelsch et al., 2006b) that already deep sedation strongly affects the functioning of heteromodal (prefrontal) cortices involved in the processing of musical structure and meaning, and that, during unconsciousness (adequate anesthesia), frequency discrimination is abolished. Thus, it is likely that effects of music during general anesthesia are only very minimal (Szmuk et al., 2008), which is consistent with previous studies that found no differences on cortisol levels (Migneault et al., 2004).

We presented participants with pre-selected music because (a) we wanted to guarantee that no lyrics were contained in the stimuli, and (b) we wanted to use a collection of stimuli with a relatively homogenous emotional quality (joyful tunes). Some participants, however, reported that they would rather have listened exclusively to music of their preferred genres. Therefore, we assume that future research could optimize results by using different selections of stimuli according to individual preferences (such as a classic, folk, jazz, etc., programs).

Conclusion

This study considered a number of methodological issues necessary to obtain substantiation of beneficial effects of music in a clinical setting according to the standards of evidence-based medicine: Our study used a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled experimental design, in which patients were randomly assigned either to a music group or to a control group. Both groups listened to a pleasant auditory stimulus (thus, the theater noise was pleasantly reduced in both groups), the music group listened to instrumental music (without lyrics), and patients of both groups underwent the same surgical procedure. Because patients of the music group had a lower propofol consumption, and lower cortisol levels (compared to the control group) during the intra-operative period, our data provide evidence that listening to music reduces sedative requirements to reach light sedation, and that music can exert stress-reducing effects during surgery under regional anesthesia. Music can be delivered to patients relatively easily, and reasonably well-priced; therefore our findings indicate that music can be used as an efficient, and efficacious adjuvant treatment to reduce stress in clinical settings.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Ayoub C. M., Rizk L. B., Yaacoub C. I., Gaal D., Kain Z. N. (2005). Music and ambient operating room noise in patients undergoing spinal anesthesia. Anesth. Analg. 100, 1316–1319 10.1213/01.ANE.0000153014.46893.9B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold M. L., Perez R. A., Puli S. R., Marshall J. B. (2006). Effect of music on patients undergoing outpatient colonoscopy. World J. Gastroenterol. 12, 7309–7312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blood A., Zatorre R. J. (2001). Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with activity in brain regions implicated in reward and emotion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 11818–11823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bringman H., Giesecke K., Thörne A., Bringman S. (2009). Relaxing music as pre-medication before surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 53, 759–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownley K. A., McMurray R. G., Hackney A. C. (1995). Effects of music on physiological and affective responses to graded treadmill exercise in trained and untrained runners. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 19, 193–201 10.1016/0167-8760(95)00007-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda M. S., Carr D. B., Lau J., Alvarez H. (2006). Music for pain relief. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2, 1–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan Y. M., Lee P. W., Ng T. Y., Ngan H. Y., Wong L. C. (2003). The use of music to reduce anxiety for patients undergoing colposcopy: a randomized trial. Gynecol. Oncol. 91, 213–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charnetski C. J., Brennan F. X., Jr., Harrison J. F. (1998). Effect of music and auditory stimuli on secretory immunoglobulin A (IgA). Percept. Mot. Skills 87, 1163–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernik D., Gillings D., Laine H., Hendler J., Silver J., Davidson A., Schwam E., Siegel J. (1990). Validity and reliability of the observer's assessment of alertness/sedation scale: study with intravenous midazolam. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 10, 244–251 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad C., Niess H., Jauch K. W., Bruns C. J., Hartl W., Welker L. (2007). Overture for growth hormone: requiem for interleukin-6? Crit. Care Med. 35, 2709–2713 10.1097/01.CCM.0000291648.99043.B9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke M., Chaboyer W., Schluter P., Hiratos M. (2005). The effect of music on preoperative anxiety in day surgery. J. Adv. Nurs. 52, 47–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R., O'Connor J. C., Freund G. G., Johnson R. W., Kelley K. W. (2008). From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 46–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers S., Suhr B. (2000). Changes of the neurotransmitter serotonin but not of hormones during short time music perception. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 250, 144–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui H., Yamashita M. (2003). The effects of music and visual stress on testosterone and cortisol in men and women. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 24, 173–180 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganidagli S., Cengiz M., Yanik M., Becerik C., Unal B. (2005). The effect of music on preoperative sedation and the bispectral index. Anesth. Analg. 101, 103–106 10.1213/01.ANE.0000150606.78987.3B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerra G., Zaimovic A., Franchini D., Palladino M., Giucastro G., Reali N., Maestri D., Caccavari R., Delsignore R., Brambilla F. (1998). Neuroendocrine responses of healthy volunteers to “techno-music”: relationships with personality traits and emotional state. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 28, 99–111 10.1016/S0167-8760(97)00071-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerra G., Zaimovic A., Mascetti G. G., Gardini S., Zambelli U., Timpano M., Raggi M. A., Brambilla F. (2001). Neuroendocrine responses to experimentally-induced psychological stress in healthy humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology 26, 91–107 10.1016/S0306-4530(00)00046-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grape C., Sandgren M., Hansson L. O., Ericson M., Theorell T. (2003). Does singing promote well-being? – an empirical study of professional and amateur singers during a singing lesson. Integr. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 38, 65–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harikumar R., Raj M., Paul A., Harish K., Kumar S. K., Sandesh K., Asharaf S., Thomas V. (2006). Listening to music decreases need for sedative medication during colonoscopy: a randomized, controlled trial. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 25, 3–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinke W., Kenntner R., Gunter T. C., Sammler D., Olthoff D., Koelsch S. (2004). Sequential effects of increasing propofol sedation on frontal and temporal cortices as indexed by auditory event-related potentials. Anesthesiology 100, 617–625 10.1097/00000542-200403000-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinke W., Koelsch S. (2005). The effects of anesthetics on brain activity and cognitive function. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 18, 625–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hucklebridge F., Clow A., Evans P. (1998). The relationship between salivary secretory immunoglobulin A and cortisol: neuroendocrine response to awakening and the diurnal cycle. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 31, 69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hucklebridge F., Lambert S., Clow A., Warburton D. M., Evans P. D., Sherwood N. (2000). Modulation of secretory immunoglobulin A in saliva: response to manipulation of mood. Biol. Psychol. 53, 25–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jääskeläinen S. K., Rinne J. O., Forssell H., Tenovuo O., Kaasinen V., Sonninen P., Bergman J. (2001). Role of the dopaminergic system in chronic pain – a fluorodopa-PET study. Pain 90, 257–260 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00409-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juslin P. N., Västfjäll D. (2008). Emotional responses to music: the need to consider underlying mechanisms. Behav. Brain Sci. 31, 559–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan D. M., Veldhuis J. D. (2003). Cortisol feedback state governs adrenocorticotropin secretory-burst shape, frequency, and mass in a dual-waveform construct: time of day-dependent regulation. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 285, R950–R961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M. E., Kain Z. N., Ayoub C., Rosenbaum S. H. (1998). The sedative and analgesic sparing effect of music. Anesthesiology 89, 300–306 10.1097/00000542-199808000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch S. (2010). Towards a neural basis of music-evoked emotions. Trends Cogn. Sci. 14, 131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch S., Fritz T., Schlaug G. (2008). Amygdala activity can be modulated by unexpected chord functions during music listening. Neuroreport 19, 1815–1819 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32831a8722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch S., Fritz T., von Cramon D. Y., Müller K., Friederici A. D. (2006a). Investigating emotion with music: an fMRI study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 27, 239–250 10.1002/hbm.20180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch S., Heinke W., Sammler D., Olthoff D. (2006b). Auditory processing during deep propofol sedation and recovery from un-consciousness. Clin. Neurophysiol. 117, 1746–1759 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch S., Offermanns K., Franzke P. (2010). Music in the treatment of affective disorders: an exploratory investigation of a new method for music-therapeutic research. Music Percept. 27, 307–316 10.1525/mp.2010.27.4.307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch S., Remppis A., Sammler D., Jentschke S., Mietchen D., Fritz T., Siebel W. A. (2007). A cardiac signature of emotionality. Eur. J. Neurosci. 26, 3328–3338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch S., Siebel W. A. (2005). Towards a neural basis of music perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9, 578–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutz G., Bongard S., Rohrmann S., Hodapp V., Grebe D. (2004). Effects of choir singing or listening on secretory immunoglobulin A, cortisol, and emotional state. J. Behav. Med. 27, 623–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laux L., Glanzmann P., Schaffner P., Spielberger C. D. (1981). Das State-Trait-Angstinventar (Testmappe mit Handanweisung, Fragebogen STAI-G Form X 1 und Fragebogen STAI-G Form X 2). Weinheim: Beltz [Google Scholar]

- Leardi S., Pietroletti R., Angeloni G., Necozione S., Ranalletta G., Del Gusto B. (2007). Randomized clinical trial examining the effect of music therapy in stress response to day surgery. Br. J. Surg. 94, 943–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux J. E. (2000). Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 23, 155–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepage C., Drolet P., Girard M., Grenier Y., DeGagné R. (2001). Music decreases sedative requirements during spinal anesthesia. Anesth. Analg. 93, 912–916 10.1097/00000539-200110000-00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeRoux F. H., Bouic P. J. D., Bester M. M. (2007). The effect of Bach's magnificat on emotions, immune, and endocrine parameters during physiotherapy treatment of patients with infectious lung conditions. J. Music Ther. 44, 156–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie K., Sessler D. I., Schroeder M., Walters K. (1995). Propofol blood concentration and the bispectral index predict suppression of learning during propofol/epidural anesthesia in volunteers. Anesth. Analg. 81, 1269–1274 10.1097/00000539-199512000-00025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCraty R., Atkinson M., Rein G. (1996). Music enhances the effect of positive emotional states on salivary IgA. Stress Med. 12, 167–175 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney C. H., Antoni M. H., Kumar M., Tims F. C., McCabe P. M. (1997a). Effects of guided imagery and music (GIM) therapy on mood and cortisol in healthy adults. Health Psychol. 16, 390–400 10.1037/0278-6133.16.4.390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney C. H., Tims F. C., Kumar A. M., Kumar M. (1997b). The effect of selected classical music and spontaneous imagery on plasma β-endorphin. J. Behav. Med. 20, 85–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon V., Levitin D. J. (2005). The rewards of music listening: response and physiological connectivity of the mesolimbic system. Neuroimage 28, 175–184 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.05.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migneault B., Girard F., Albert C., Chouinard P., Boudreault D., Provencher D., Todorov A., Ruel M., Girard D. C. (2004). The effect of music on the neurohormonal stress response to surgery under general anesthesia. Anesth. Analg. 98, 527–532 10.1213/01.ANE.0000096182.70239.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miluk-Kolasa B., Obminski Z., Stupnicki R., Golec L. (1994). Effects of music treatment on salivary cortisol in patients exposed to pre-surgical stress. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. 102, 118–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möckel M., Störk T., Vollert J., Röcker L., Danne O., Hochrein H., Eichstädt H., Frei U. (1995). Stressreduktion durch Musikhören: einfluss auf Stresshormone, Hämodynamik und psychisches Befinden bei Patienten mit arterieller Hypertonie und bei Gesunden [Stress reduction through listening to music: effects on stress hormones, haemodynamics and psychological state in patients with arterial hypertension and in healthy subjects]. Dtsh. Med. Wochenschr. 120, 745–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgane J. P., Panksepp J. (1980) “Physiology of the hypothalamus,” in Handbook of the Hypothalamus, eds Morgane J. P., Panksepp J. (New York: Dekker, University of Michigan; ), 680 [Google Scholar]

- Nater U. M., Abbruzzese E., Krebs M., Ehlert U. (2006). Sex differences in emotional and psychophysiological responses to musical stimuli. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 62, 300–308 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2006.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuys R., Voogd J., Van Huijzen C., van Huijzen C. (2007). The Human Central Nervous System, 4th Edn. Berlin: Springer; 17366645 [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson U., Unosson M., Rawal N. (2005). Stress reduction and analgesia in patients exposed to calming music postoperatively: a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Anesthesiol. 22, 96–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyama T., Hatano K., Sato Y., Kudo M., Spintge R., Droh R. (1983). “Endocrine effects of anxiolytic music in dental patients,” in Angst, Schmerz und Musik in der Anästhesie, eds Droh R., Spintge R. (Grenzach: Editiones Roche; ), 143–146 [Google Scholar]

- Pani L., Porcella A., Gessa G. L. (2000). The role of stress in the pathophysiology of the dopaminergic system. Mol. Psychiatry 5, 14–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips A. C., Carroll D., Evans P., Bosch J. A., Clow A., Hucklebridge F., Der G. (2006). Stressful life events are associated with low secretion rates of immunoglobulin A in saliva in the middle aged and elderly. Brain Behav. Immun. 20, 191–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiroga C., Kreutz G., Bongard S. (2011). “Endokrine und immunologische Wirkungen von Musik [Endocrine and immunological effects of music],” in Psychoneuroimmunologie und Psychotherapie, ed. Schubert C. (Stuttgart: Schattauer; ), 248–262 [Google Scholar]

- Rudin D., Kiss A., Wetz R. V., Sottile V. M. (2007). Music in the endoscopy suite: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Endoscopy 39, 507–510 10.1055/s-2007-966362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider N., Schedlowski M., Schürmeyer T. H., Becker H. (2001). Stress reduction through music in patients undergoing cerebral angiography. Neuroradiology 43, 472–476 10.1007/s002340000522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C. D., Gorsuch R. L., Lushene R. E. (1970). State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press [Google Scholar]

- Szmuk P., Aroyo N., Ezri T., Muzikant G., Weisenberg M., Sessler D. I. (2008). Listening to music during anesthesia does not reduce the sevoflurane concentration needed to maintain a constant bispectral index. Anesth. Analg. 107, 77–80 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181733e16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thalheimer W., Cook S. (2002). How to Calculate Effect Sizes from Published Research Articles: A Simplified Methodology. Available at: http://work-learning.com/effect_sizes.htm (accessed February 20, 2010).

- Uedo N., Ishikawa H., Morimoto K., Ishihara R., Narahara H., Akedo I., Ioka T., Kaji I., Fukuda S. (2004). Reduction in salivary cortisol level by music therapy during colonoscopic examination. Hepatogastroenterology 51, 451–453 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderArk S. D., Ely D. (1992). Biochemical and galvanic skin responses to music stimuli by college students in biology and music. Percept. Mot. Skills 74, 1079–1090 10.2466/PMS.74.4.1079-1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollert J. O., Störk T., Rose M., Möckel M. (2003). Music as adjuvant therapy for coronary heart disease. Therapeutic music lowers anxiety, stress and beta-endorphin concentrations in patients from a coronary sport group. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 128, 2712–2716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. M., Kulkarni L., Dolev J., Kain Z. N. (2002). Music and preoperative anxiety: a randomized, controlled study. Anesth. Analg. 94, 1489–1494 10.1097/00000539-200206000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West J., Otte C., Geher K., Johnson J., Mohr D. C. (2004). Effects of Hatha yoga and African dance on perceived stress, affect, and salivary cortisol. Ann. Behav. Med. 28, 114–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. W., Fan Y., Manyande A., Tian Y. K., Yin P. (2005). Effects of music on target-controlled infusion of propofol requirements during combined spinal-epidural anesthesia. Anesthesia 60, 990–994 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04299.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]