Abstract

We report a case of a 59-year-old man with testicular germ cell tumor who showed new hypermetabolic lesions at the left axillary lymph nodes on a post-treatment positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan. The hypermetabolic lesions were found to be caused by an influenza vaccination 10 days prior to the PET-CT scan and disappeared without additional treatment. To date, he is alive with complete remission.

Keywords: False positive reactions, Positron-emission tomography, Vaccination

INTRODUCTION

Serum tumor markers and computed tomography (CT) are primarily used for patients with germ cell tumors to evaluate efficacy of therapy, residual disease, or disease progression. Additionally, 18F-fluoro-deoxyglucose (18F-FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET), which measures glucose metabolism, can provide the advantage of identifying and predicting the viability of residual tumors, which cannot be readily differentiated from non-viable tissue, such as necrotic or fibrotic tissue, in CT scans [1,2]. Here, we report a case showing false-positive hypermetabolic lesions caused by an influenza vaccination during evaluation of a post-chemotherapy PET-CT scan.

CASE REPORT

A 59-year-old man presented with a mediastinal mass on a chest roentgenogram. Chest CT demonstrated enlarged right hilar and paratracheal lymph nodes, which were hypermetabolic on whole body 18F-FDG PET-CT (Fig. 1). However, the PET-CT scan showed no other hypermetabolic lesion. Bronchoscopy revealed only extrinsic compression of the right bronchus with no endobronchial lesion. Thus, video-assisted thoracic surgery was performed for a biopsy of the paratracheal lymph nodes. The histology was consistent with seminoma, which was supported by immunostaining results: cytokeratin (+), placental alkaline phosphatase (+), alpha-fetoprotein (αFP) (-), beta-human choriogonadotropin (β-hCG) (-), leukocyte common antigen (-), and CD30 (-). Ultrasound of the testicles showed microlithiasis in the right testis and serum αFP and β-hCG were in the normal range. After being diagnosed with burned-out testicular seminoma with multiple mediastinal and hilar lymph node metastases, he received four cycles of chemotherapy, consisting of ifosfamide, cisplatin, and etoposide. After completion of chemotherapy, he underwent whole-body PET-CT to evaluate the response and residual masses. In the PET-CT scan, hypermetabolic lesions in right hilar and paratracheal lymph nodes disappeared, while new multiple hypermetabolic lesions appeared in enlarged left axillary lymph nodes (Fig. 2). In-depth questioning of the patient revealed that he received an influenza vaccination 10 days prior to the PET-CT scan in his left deltoid muscle, an area that drains to the left axillary lymph node chain, at a primary care office. We decided to perform a chest CT 3 weeks thereafter and the result revealed no lymphadenopathy in the left axillary area and no initial metastatic lymphadenopathy (Fig. 3). Since undergoing planned left radical orchiectomy, which showed microcalcification without evidence of the tumor, he is now being followed up regularly with no evidence of recurrence.

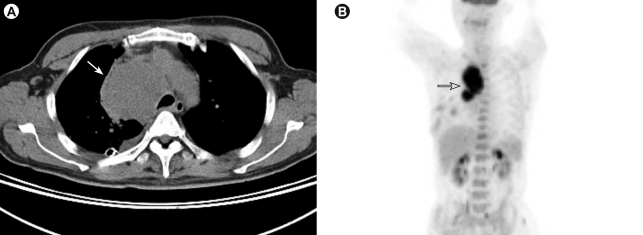

Figure 1.

Chest computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET) before treatment. Chest CT shows enlarged right hilar and paratracheal lymph nodes (A, solid arrow), which are hypermetabolic on 18F-fluoro-deoxyglucose-PET scans (B, empty arrow).

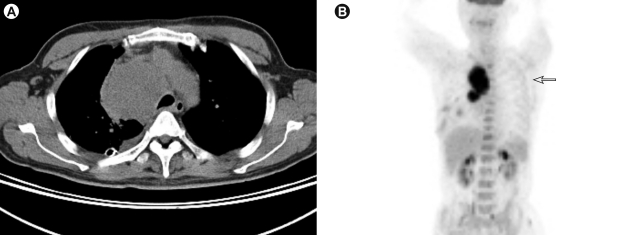

Figure 2.

Chest computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET) after treatment. Chest CT and PET scans show disappearance of previous lesions, but new appearance of hypermetabolic enlarged axillary lymph nodes (A, solid arrow; B, empty arrow).

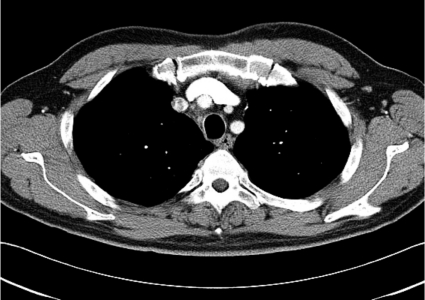

Figure 3.

Chest computed tomography 4 weeks after surveillance. Axillary lymphadenopathy disappeared (solid arrow).

DISCUSSION

The identification of viable tumor cells after systemic chemotherapy is very important in the management of testicular cancer to avoid both unnecessary surgical exploration and additional unnecessary chemotherapy or radiotherapy, which can increase short-term and long-term toxicities. However, after tumor markers, such as αFP and β-hCG, are found to be in the normal range, approximately 25-30% of patients with germ cell tumors will still be left with a residual mass, for which conventional imaging modalities-such as a CT scan-cannot differentiate viable tumors from fibrotic or necrotic tissue [1]. PET or PET-CT is useful in identifying the presence of viable tumors in post-treatment residual tumors with higher sensitivities and specificities than CT [2]. However, as with all modalities, PET or PET-CT has some limitations. False-negative results can occur with the presence of a mature teratoma or a very small tumor, or if early scans are performed within 10-14 days from commencement of chemotherapy [3-5]. Conversely, false-positive results can be found with the presence of inflammatory changes or infection [6,7]. Importantly, the recognition of a false-positive result is very important to avoid unnecessary surgical resection or other toxic treatment. Our patient showed very favorable radiologic and metabolic responses to chemotherapy, but also the new appearance of hypermetabolic lesions in an unusual site. Fortunately, careful history documentation revealed the vaccination before PET scanning, which might have caused inflammation, with local lymphocyte activation and proliferation for antigen processing. Additionally, we showed spontaneous regression using CT after a 3-week observation period. However, no definite time-course of node activation was confirmed. Waiting at least 4 weeks after vaccination could minimize false-positives from vaccine immunity to tumor involvement of lymph nodes [8].

In summary, we report the case of a man with testicular germ cell tumor whose response to treatment was complicated by false-positive findings on a PET-CT scan caused by vaccination or inflammation. Recently, although PET or PET-CT studies are widely used to predict the response to treatment in germ cell tumors as well as in lymphoma or lung cancer, precautions must be taken when interpreting the results of PET-CT scans, particularly when they are not clinically correlated.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Puc HS, Heelan R, Mazumdar M, et al. Management of residual mass in advanced seminoma: results and recommendations from the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:454–460. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.2.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Santis M, Becherer A, Bokemeyer C, et al. 2-18fluoro-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography is a reliable predictor for viable tumor in postchemotherapy seminoma: an update of the prospective multicentric SEMPET trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1034–1039. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugawara Y, Zasadny KR, Grossman HB, Francis IR, Clarke MF, Wahl RL. Germ cell tumor: differentiation of viable tumor, mature teratoma, and necrotic tissue with FDG PET and kinetic modeling. Radiology. 1999;211:249–256. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.1.r99ap16249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cremerius U, Effert PJ, Adam G, et al. FDG PET for detection and therapy control of metastatic germ cell tumor. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:815–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hain SF, O'Doherty MJ, Timothy AR, Leslie MD, Harper PG, Huddart RA. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the evaluation of germ cell tumours at relapse. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:863–869. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kline RM. PET scan hypermetabolism induced by influenza vaccination in a patient with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46:389. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iyengar S, Chin B, Margolick JB, Sabundayo BP, Schwartz DH. Anatomical loci of HIV-associated immune activation and association with viraemia. Lancet. 2003;362:945–950. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14363-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCool D, Buscombe JR, Hilson AJ. Influenza vaccine and FDG-PET. Lancet. 2003;362:2024. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)15034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]