Abstract

Somitogenesis is controlled by cyclic genes such as Notch effectors and by the wave front established by morphogens such as Fgf8, but the precise mechanism of how these factors are coordinated remains to be determined. Here, we show that effectors of Notch and Fgf pathways oscillate in different dynamics and that oscillations in Notch signaling generate alternating phase shift, thereby periodically segregating a group of synchronized cells, whereas oscillations in Fgf signaling released these synchronized cells for somitogenesis at the same time. These results suggest that Notch oscillators define the prospective somite region, while Fgf oscillators regulate the pace of segmentation.

Keywords: somitogenesis, oscillation, Notch, Fgf, Mesp2, clock and wave front model

Somite formation occurs periodically by segmentation and maturation of a block of cells in the anterior presomitic mesoderm (PSM) (Dequéant and Pourquié 2008). It is thought that the pace of segmentation depends on the clock controlled by cyclic genes such as Notch signaling molecules, while the timing of maturation depends on the wave front established by morphogens such as Fgf8 (Dubrulle et al. 2001; Sawada et al. 2001; Lewis et al. 2009). However, Notch signaling oscillations become slower than the pace of segmentation as the oscillations are propagated anteriorly (Palmeirim et al. 1997; Giudicelli et al. 2007), raising the question of whether such a slowing oscillator regulates the segmentation pace. Furthermore, Fgf signaling seems to sweep back at a steady speed as the PSM grows (Dubrulle and Pourquié 2004; Aulehla and Pourquié 2010), raising another question of whether the release from Fgf signaling occurs at different times between the anterior and posterior cells even in the same prospective somites.

In the mouse PSM, Hes7 is expressed in an oscillatory manner and induces oscillatory expression of Lunatic fringe (Lfng), a modulator of Notch signaling (Bessho et al. 2001; Dale et al. 2003; Serth et al. 2003). Lfng oscillations in turn lead to cyclic formation of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) (Huppert et al. 2005; Morimoto et al. 2005), an active form of Notch, which then periodically induces expression of Mesp2, an essential gene for the segmentation and rostro–caudal patterning of each somite (Saga et al. 1997). Mesp2 expression depends on NICD and Tbx6 and occurs after the release from Fgf and Wnt signaling in the whole S-1 region, a group of cells that forms a prospective somite (Evrard et al. 1998; Zhang and Gridley 1998; Aulehla et al. 2008; Oginuma et al. 2008, 2010). High-resolution in situ hybridization demonstrated that S-1 cells synchronously exhibit nuclear dots of Mesp2 signals, indicating synchronous initiation of Mesp2 transcription in the whole S-1 region (Oginuma et al. 2008, 2010). In Lfng-null mice, which have segmentation defects (Evrard et al. 1998; Zhang and Gridley 1998), Mesp2 expression becomes randomized in S-1 cells, displaying a salt-and-pepper pattern (Oginuma et al. 2010). These results suggest that synchronous Mesp2 expression in S-1 cells is important for somite formation. However, how slowing Notch signaling oscillators and steadily regressing Fgf and Wnt signaling regulate periodic and synchronous Mesp2 expression in S-1 cells remains to be determined.

Here we found that Notch and Fgf signaling effectors oscillate with different dynamics and that oscillations in Notch signaling periodically segregate a group of synchronized cells, whereas oscillations in Fgf signaling release these synchronized cells for somitogenesis at the same time. These results suggest that Notch oscillators define the prospective somite region, while Fgf oscillators regulate the pace of segmentation, thereby linking the clock and the wave front.

Results and Discussion

Oscillations in Notch and Fgf pathways show different dynamics

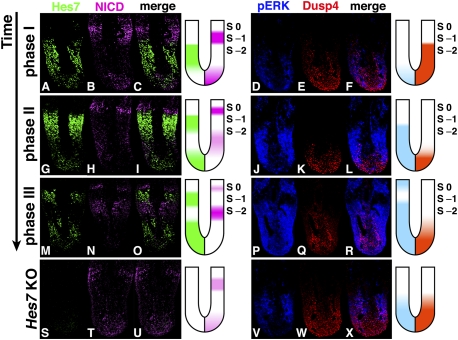

To understand the dynamics of oscillators, we first examined the spatiotemporal relationship between Hes7 and NICD by immunohistochemistry. When Hes7 protein was expressed in the middle PSM (Fig. 1A,C), NICD was expressed in S-1 and the posterior PSM (phase I) (Fig. 1B,C). During this phase, Hes7 protein was also expressed by subsets of cells in the posterior end of the PSM (Fig. 1A,C). When Hes7 protein expression moved to the anterior PSM, NICD expression in the posterior PSM and S-1 also moved anteriorly (phase II) (Figure 1G–I). Hes7 expression further moved to S-1, and new Hes7 protein expression was initiated in the posterior PSM (phase III) (Fig. 1M–O). During this phase, NICD expression moved to S0 and S-2 (Fig. 1N,O). Thus, NICD and Hes7 protein were expressed in a mutually exclusive manner during all three phases, except for the posterior end of the PSM. In addition, both the Hes7 and NICD expression domains were narrowed as they moved anteriorly, and formed two regions with alternating phase shifts: Hes7+NICD− (S-1) and Hes7−NICD+ (S-2) (Fig. 1M–O). In Hes7-null mice, NICD was expressed steadily in the PSM (Fig. 1S–U), indicating that dynamic NICD expression depends on Hes7.

Figure 1.

Dynamic expression of Notch and Fgf signaling molecules in the PSM. Immunostaining of the PSM sections of E10.5 wild-type (A–F, phase I, n = 4; G–L, phase II, n = 5; M–R, phase III, n = 4), and Hes7 knockout (KO) (S–X, n = 8) embryos. Each row shows the same embryo. Double-staining of Hes7 and NICD and of pERK and Dusp4 was performed in the same sections. NICD and pERK oscillations showed different dynamics between each other in the wild type. Hes7-null mice showed a single pattern of NICD, pERK, and Dusp4 expression, indicating that NICD, pERK, and Dusp4 oscillations depend on Hes7.

We next examined the spatiotemporal profiles of Fgf signaling molecules. Hes7 induces oscillatory expression of Dusp4, an inhibitor of Fgf signaling (Niwa et al. 2007), which in turn leads to cyclic formation of the Fgf effector phosphorylated ERK (pERK) (Sawada et al. 2001; Delfini et al. 2005; Niwa et al. 2007). During phase I, Dusp4 was expressed in the posterior to middle PSM, while pERK expression was low (Fig. 1D–F). During phase II, Dusp4 expression was down-regulated, while pERK expression was up-regulated in the posterior to middle PSM (Fig. 1J–L). During phase III, Dusp4 expression was somewhat up-regulated, while pERK expression was further up-regulated in the posterior to S-2 region and also appeared in S0 (Fig. 1P–R). Thus, pERK expression occurred in an oscillatory manner in the posterior to S-2 region. Hes7-null mice showed a single pattern of pERK and Dusp4 expression (Fig. 1V–X), indicating that pERK and Dusp4 oscillations depend on Hes7. These results indicated that Hes7-dependent NICD and pERK oscillations showed different dynamics between each other: NICD oscillation displayed a band propagation pattern from the posterior to S0, while pERK oscillation displayed an on–off pattern in the posterior to S-2.

Notch signaling is required for segregation of synchronized regions

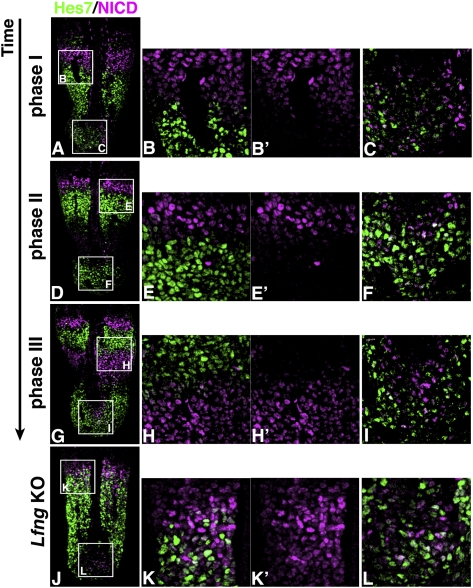

The expression patterns were further examined at a single-cell level. NICD and Hes7 protein expression were clearly separated in the middle to anterior PSM (Fig. 2A,B,B′,D,E,E′,G,H,H′). In contrast, in the posterior end of the PSM, NICD+ cells and Hes7+ cells were intermingled, and subsets of cells even coexpressed NICD and Hes7 in all three phases (Fig. 2A,C,D,F,G,I). Thus, synchronization and segregation of Hes7 and NICD oscillations were not complete in the posterior end but became evident in the middle to anterior regions.

Figure 2.

Lfng-dependent synchronization and segregation of Hes7 and NICD expression. (A–I) Immunostaining of Hes7 and NICD in the PSM sections of E10.5 wild-type embryos (A,D,G). Boxed regions are enlarged in B, C, E, F, H, and I. (B,B′,E,E′,H,H′) Note that, in the anterior regions, Hes7 and NICD expression were well segregated, and that expression of each factor was well synchronized between neighboring cells. (C,F,I) In contrast, in the posterior end, Hes7- and NICD-expressing cells were intermingled, and many cells coexpressed Hes7 and NICD, indicating that Hes7 and NICD expression are not synchronized or segregated (n = 16). (J–L) Immunostaining of the PSM section of an E10.5 Lfng-null embryo. Hes7 and NICD expression are not well segregated in the anterior (K) and posterior (L) regions (n = 5).

We next asked how the synchronization is regulated in the PSM. It was proposed previously that Notch signaling is involved in synchronization of oscillations in zebrafish (Jiang et al. 2000; Horikawa et al. 2006; Riedel-Kruse et al. 2007). To address this issue, we examined Lfng-null mice, where oscillations in Notch signaling are disrupted (Morimoto et al. 2005). In the posterior end of the PSM of Lfng-null mice, Hes7- and NICD-expressing cells were intermingled, and some cells coexpressed Hes7 and NICD (Fig. 2J,L). Thus, the expression pattern was not significantly affected compared with the wild type in the posterior end of the PSM (Fig. 2C,F,I,L). However, Hes7 and NICD expression domains were not clearly segregated in either the S0 or S-1 region of Lfng-null mice (Fig. 2J,K,K′): Hes7+ cells and NICD+ cells were scattered throughout the PSM and were intermingled with each other (Fig. 2J,K). Some cells even coexpressed Hes7 and NICD, similar to what occurred in the posterior end of the PSM (Fig. 2J–L). These results indicated that Lfng regulates synchronization and segregation of Hes7 and NICD oscillations, thereby forming alternating phase-shifting regions: S-1 and S-2. It was shown previously that, in Lfng-null mice, NICD expression is nonoscillatory (Morimoto et al. 2005), whereas another study indicated that it is oscillatory (Ferjentsik et al. 2009). This discrepancy remains to be clarified, but our results indicated that synchronized NICD oscillation was severely impaired in Lfng-null mice (Fig. 2J–L).

We further analyzed the oscillation dynamics by time-lapse imaging with Hes7 promoter-driven UbLuc reporter mice (Masamizu et al. 2006; Takashima et al. 2011). In the wild type, the reporter expression oscillated with high amplitudes (Supplemental Movie S1), and, from this imaging, the spatiotemporal profiles were produced (Supplemental Figs. S1, S2A,G). In Hes7-null mice, the reporter expression did not oscillate, leading to severe segmentation defects (Supplemental Fig. S2C,F,G; Supplemental Movie S3). In Lfng-null mice, the reporter expression oscillated with the same periodicity as that of the control but showed ambiguous and broader patterns (Supplemental Fig. S2B,G; Supplemental Movie S2). Uncx4.1 expression was also ambiguously segmented in these mice compared with the control (Supplemental Fig. S2D,E). These results indicated that Lfng is required for narrowing and clear segregation of the Hes7+ and NICD+ domains, leading to robust oscillatory expression of Hes7 and NICD.

pERK oscillations release the whole S-1 region for differentiation at the same time

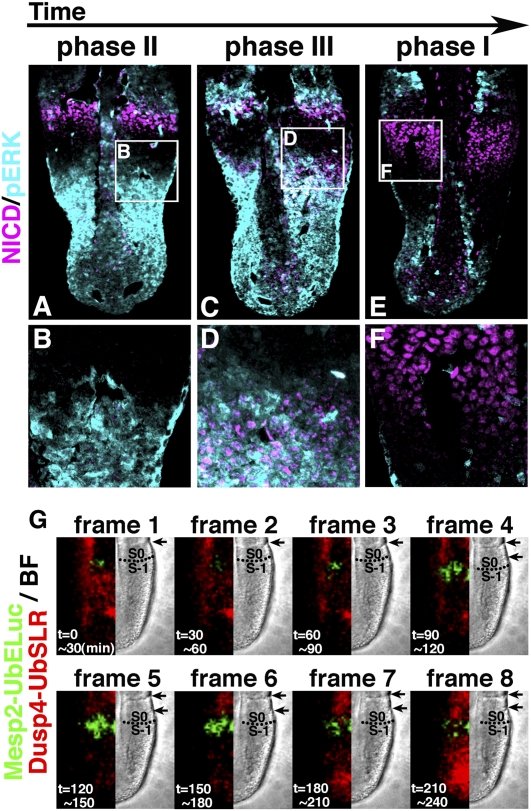

We next examined the relationship between NICD and pERK. During phases II and III, the posterior NICD expression moved from the middle to S-2 region, while pERK was expressed from the posterior to S-2 region (Fig. 3A–D), indicating that the posterior NICD domain was covered by the pERK domain. However, during phase I, when S-2 became S-1 after segmentation, pERK expression was down-regulated and the whole NICD domain in S-1 was freed from pERK (Fig. 3E,F). It was reported previously that Mesp2 expression is synchronously initiated in S-1 cells during this period (Oginuma et al. 2008, 2010). Because Mesp2 expression is known to be repressed by Fgf signaling (Oginuma et al. 2008), the time when the NICD domain in S-1 is freed from pERK is likely to coincide with the onset of Mesp2 expression.

Figure 3.

Phase shifting between NICD and pERK oscillations and onset of Mesp2 expression. (A–F) Immunostaining of Hes7 and pERK in the PSM sections of E10.5 wild-type embryos (A, n = 5; C, n = 6; E, n = 4). Boxed regions are enlarged in B, D, and F. (G) Time-lapse imaging of Dusp4-UbSLR (red) and Mesp2-UbEluc (green) reporter expression in the E10.5 PSM (n = 3). Note the spatiotemporal coincidence of Dusp4 disappearance and Mesp2 onset (just below the broken line in frame 4).

To directly test this idea, we performed time-lapse imaging of Mesp2 expression and Fgf–ERK signaling activity by using red (SLR) and green (ELuc) luciferase reporters (Nakajima et al. 2004, 2010). Because both luciferase proteins are too stable to monitor oscillatory expression, they were destabilized by ubiquitination (UbSLR and UbELuc). Mesp2 transcription was monitored by Mesp2 promoter-driven UbELuc (Mesp2-UbEluc), while Fgf–ERK signaling activity was monitored by Dusp4 promoter-driven UbSLR (Dusp4-UbSLR). The expression from the Dusp4-UbSLR reporter closely mimicked pERK expression in the PSM (Supplemental Fig. S3A–E). Transgenic mice carrying the Mesp2-UbEluc and Dusp4-UbSLR reporters were generated, and explant cultures of the posterior half of embryos at embryonic day 10.5 (E10.5) were performed for red and green bioluminescence imaging (Fig. 3G; Supplemental Movie S4). During phases II and III, Fgf–ERK signaling (Fig. 3G, red) was active from the posterior to the S-2 region (Fig. 3G, frames 1–3), although the activity gradually decreased. After segmentation, Fgf–ERK signaling was mostly negative, and Mesp2 expression (Fig. 3G, green) was initiated in the S-1 region (Fig. 3G, frame 4, bottom arrow indicates a newly formed boundary, while a broken line shows a prospective boundary). During phase I, Mesp2 expression occurred in the whole S-1 region (Fig. 3G, frames 4–6). During phase II, Mesp2 expression was reduced to the rostral region of S-1, while Fgf–ERK signaling was gradually up-regulated (Fig. 3G, frames 7,8). These results showed that Mesp2 expression was initiated in the whole S-1 region just after being freed from Fgf–ERK signaling.

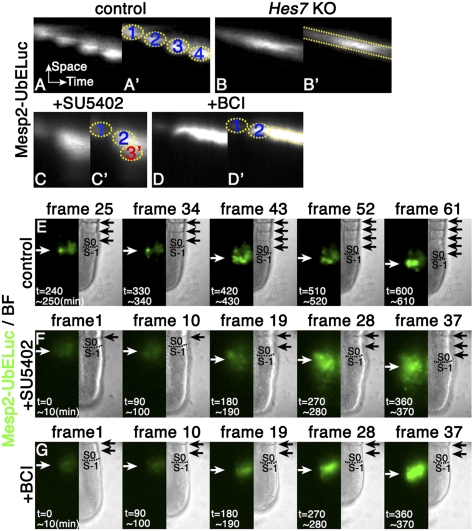

Fgf signaling is required for periodic expression of Mesp2

The above results indicated that oscillations in Notch signaling make a group of cells to express NICD synchronously, while oscillations of Fgf–ERK signaling release the NICD+ cells from inhibition, thereby enabling all of the S-1 cells to express Mesp2 at the same time. We next examined how Mesp2 expression is affected without oscillators. Time-lapse imaging analysis showed that, in the wild type, Mesp2 expression occurred periodically in S-1 (Fig. 4A,A′,E; Supplemental Fig. S4A), as reported previously (Saga et al. 1997). In Hes7-null mice, the pERK expression domain did not oscillate, but regressed at a steady speed (Fig. 1V–X), which was also confirmed by the time-lapse imaging of the Dusp4-UbSLR reporter expression (Supplemental Fig. S3F). In these mice, Mesp2 expression also did not occur periodically, but regressed at a steady speed (Fig. 4B,B′; Supplemental Fig. S4B). Thus, in Hes7-null mice, the onset of Mesp2 expression occurred at different times between the anterior and posterior cells even in the same prospective somites, raising the possibility that desynchronized onset of Mesp2 expression leads to segmentation and patterning defects. These results indicated that oscillations in Fgf–ERK signaling are required for periodic expression of Mesp2 in the whole S-1 region.

Figure 4.

Fgf signaling-dependent periodic expression of Mesp2. Time-lapse imaging of Mesp2 expression with Mesp2-UbEluc reporter mice. Mesp2 expression occurred periodically in the control (A,A′, n = 5), whereas it occurred steadily in Hes7 knockout (KO) (B,B′, n = 4) embryos. (C,C′) In explants treated with the Fgf inhibitor SU5402 (30 μM), Mesp2 expression occurred precociously (n = 3). (D,D′) In explants treated with the Dusp inhibitor BCI (2 μM), Mesp2 expression regressed steadily (n = 5). The filmstrips of A, C, and D are shown in E–G, respectively. Somite boundaries are indicated by black arrows. Prospective somite boundaries are shown by broken lines. Dominant positions of Mesp2 expression are indicated by white arrows.

We further analyzed the effect of oscillations in Fgf–ERK signaling on Mesp2 expression. We first attempted continuous inactivation of Fgf signaling. However, in Fgfr1-null mice, oscillations of both Hes7 and Lfng are lost (Niwa et al. 2007), and therefore the observed defects could be due to loss of oscillations in both Notch and Fgf signaling. We and others showed previously that treatment with Fgf signaling inhibitors rapidly blocked Fgf signaling but only slowly affected Notch signaling (Niwa et al. 2007; Wahl et al. 2007). Thus, we examined the early effect of SU5402, an inhibitor of Fgf signaling, on Mesp2 expression. SU5402 treatment completely abolished the Dusp4-UbSLR reporter expression (Supplemental Fig. S3G), suggesting that Fgf–ERK activities were lost. Time-lapse imaging analysis demonstrated that, without Fgf–ERK activities, Mesp2 expression occurred continuously and prematurely (Fig. 4C,C′, the third signal appeared prematurely and was fused with the second), compared with the wild type (Fig. 4A,A′). In the wild type, Mesp2 expression was initiated in S-1 just after segmentation (Fig. 4E, control, frames 43,61), whereas, in SU5402-treated PSM, the new Mesp2 expression occurred prematurely in S-2 and the further posterior region before segmentation (Fig. 4F, +SU5402, frame 28, white arrow, note that the next segmentation is indicated by the lowest black arrow in frame 37). We next attempted continuous activation of Fgf signaling by treatment of the Dusp inhibitor BCI (Molina et al. 2009). BCI treatment led to steady expression of the Dusp4-UbSLR reporter (Supplemental Fig. S3H), suggesting that Fgf–ERK activities were steadily active. Time-lapse imaging analysis showed that Mesp2 expression was not periodic but regressed steadily in the presence of BCI (Fig. 4D,D′,G), suggesting that Mesp2 expression occurred in the anterior PSM after steady regression of Fgf–ERK activities. These results support the idea that Fgf–ERK-dependent oscillations regulate the periodic onset of Mesp2 expression in S-1.

It has been shown that Notch signaling is required for synchronization of oscillations between PSM cells in zebrafish (Jiang et al. 2000; Horikawa et al. 2006; Riedel-Kruse et al. 2007), and our study agreed with this idea but showed that Lfng is required for synchronization in mice. Hes7 and NICD oscillations become ∼1.5-fold slower in the anterior PSM than in the posterior, and it is likely that these slowing oscillations lead to narrowing and segregation of the synchronized regions (mathematical modeling; Supplemental Figs. S5–S8). If these oscillations do not slow in the anterior PSM, the somite sizes are likely to be severely impaired (mathematical modeling; Supplemental Fig. S9). Thus, the slowing oscillations in Notch signaling are important to define the prospective somite region. Oscillations in Fgf signaling then periodically free the NICD domain from inhibition, thereby inducing Mesp2 expression in the whole S-1 region at the same time (Fig. 5). These features agree well with the traditional concept of a “clock and wave front model” (Cooke and Zeeman 1976): Notch oscillators constitute the clock, while Fgf oscillators constitute the rippled wave front. Importantly, these oscillators are coupled by Hes7 in the posterior PSM but are phase-shifting in the anterior PSM. Our results indicated that Notch and Fgf oscillators regulate the periodicity in space and time, respectively, and that Hes7 integrates these oscillators, thereby linking the clock and the wave front.

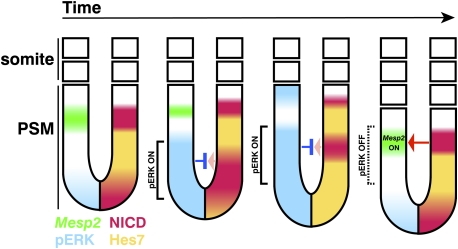

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of dynamic expression of Hes7, NICD, pERK, and Mesp2. (Left three panels) The posterior NICD domain moves anteriorly and narrows, while the pERK domain expands anteriorly, covering the NICD domain. (Right panel) After segmentation, pERK expression is down-regulated, and NICD now induces Mesp2 expression in the S-1 region. Thus, oscillations in Notch signaling periodically segregate a group of synchronized cells, and oscillations in Fgf signaling release these synchronized cells for somitogenesis at the same time.

Materials and methods

Immunohistochemistry

Whole-mount immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously (Bessho et al. 2003). Immunostaining was performed with 4-μm paraffin sections of E10.5 embryos as described previously with a minor modification (Morimoto et al. 2005). Antibodies against Hes7 (Bessho et al. 2003), Dusp4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), pERK, and NICD (Cell Signaling Technology) were used. High-power pictures were made by stacking several sequential confocal images (total, 5 μm).

Generation of luminescence reporter mice and PSM culture

Generation of UbLuc reporter mice and a culture condition were described previously (Bessho et al. 2001; Masamizu et al. 2006). For Mesp2-UbELuc and Dusp4-UbSLR mice, the regions from ATG to the stop codon of the Mesp2 and Dusp4 genomes were replaced with ubiquitinated green and red luciferase cDNAs by using BAC recombineering. The fragment containing 7.3 kb of the Mesp2 promoter or 8.2 kb of the Dusp4 promoter as well as 0.5 kb of the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) was retrieved into pBS vector. Genotypes were determined by PCR using the primers 5′-CAGAGTCTACCTCCGCCAACATC-3′ and 5′-CAGGTACTTGGAGTGAGACACCC-3′ for ELuc and 5′-TTCCACCACGCCTTCGGACTGTT-3′ and 5′-CACCTGGTAGCCCTTGTACTTGAT-3′ for SLR.

Time-lapse imaging of luminescence and image analysis

Time-lapse imaging of luminescence was captured as was described previously (Masamizu et al. 2006). We used ImageJ software for time-lapse imaging analysis. To make spatiotemporal profiles, we first applied a median filter to Hes7-UbLuc stack images and a spike-noise filter to Mesp2-UbELuc and Dusp4-UbSLR stack images to remove the cosmic rays. Then, we got the resliced stack images in the anterior–posterior axis with average or median values and arranged them from left to right in the temporal order. To obtain clear dynamic Dusp4-UbSLR expression in dual-color images, we showed only the modified values where minimal values were subtracted from filtered images in each position.

Acknowledgments

We thank Randy Johnson, Yoshihiro Nakajima, Masayuki Oginuma, and Yumiko Saga for mutant mice, other materials, and comments. We also thank Yukari Tateiwa for experimental support. This work was supported by the Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan. Y.N. was supported by Research Fellowships of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.2035311.

Supplemental material is available for this article.

References

- Aulehla A, Pourquié O 2010. Signaling gradients during paraxial mesoderm development. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2: a000869 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aulehla A, Wiegraebe W, Baubet V, Wahl MB, Deng C, Taketo M, Lewandoski M, Pourquié O 2008. A β-catenin gradient links the clock and wavefront systems in mouse embryo segmentation. Nat Cell Biol 10: 186–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessho Y, Sakata R, Komatsu S, Shiota K, Yamada S, Kageyama R 2001. Dynamic expression and essential functions of Hes7 in somite segmentation. Genes Dev 15: 2642–2647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessho Y, Hirata H, Masamizu Y, Kageyama R 2003. Periodic repression by the bHLH factor Hes7 is an essential mechanism for the somite segmentation clock. Genes Dev 17: 1451–1456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke J, Zeeman EC 1976. A clock and wavefront model for control of the number of repeated structures during animal morphogenesis. J Theor Biol 58: 455–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale JK, Maroto M, Dequéant ML, Malapert P, McGrew M, Pourquié O 2003. Periodic notch inhibition by lunatic fringe underlies the chick segmentation clock. Nature 421: 275–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfini MC, Dubrulle J, Malapert P, Chal J, Pourquié O 2005. Control of the segmentation process by graded MAPK/ERK activation in the chick embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 11343–11348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dequéant ML, Pourquié O 2008. Segmental patterning of the vertebrate embryonic axis. Nat Rev Genet 9: 370–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubrulle J, Pourquié O 2004. fgf8 mRNA decay establishes a gradient that couples axial elongation to patterning in the vertebrate embryo. Nature 427: 419–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubrulle J, McGrew MJ, Pourquié O 2001. FGF signaling controls somite boundary position and regulates segmentation clock control of spatiotemporal Hox gene activation. Cell 106: 219–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evrard YA, Lun Y, Aulehla A, Gan L, Johnson RL 1998. lunatic fringe is an essential mediator of somite segmentation and patterning. Nature 394: 377–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferjentsik Z, Hayashi S, Dale JK, Bessho Y, Herreman A, De Strooper B, del Monte G, de la Pompa JL, Maroto M 2009. Notch is a critical component of the mouse somitogenesis oscillator and is essential for the formation of the somites. PLoS Genet 5: e1000662 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giudicelli F, Ozbudak EM, Wright GJ, Lewis J 2007. Setting the tempo in development: an investigation of the zebrafish somite clock mechanism. PLoS Biol 5: e150 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horikawa K, Ishimatsu K, Yoshimoto E, Kondo S, Takeda H 2006. Noise-resistant and synchronized oscillation of the segmentation clock. Nature 441: 719–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppert SS, Ilagan MX, De Strooper B, Kopan R 2005. Analysis of Notch function in presomitic mesoderm suggests a γ-secretase-independent role for presenilins in somite differentiation. Dev Cell 8: 677–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang YJ, Aerne BL, Smithers L, Haddon C, Ish-Horowicz D, Lewis J 2000. Notch signaling and the synchronization of the somite segmentation clock. Nature 408: 475–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J, Hanisch A, Holder M 2009. Notch signaling, the segmentation clock, and the patterning of vertebrate somites. J Biol 8: 44 doi: 10.1186/jbiol145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masamizu Y, Ohtsuka T, Takashima Y, Nagahara H, Takenaka Y, Yoshikawa K, Okamura H, Kageyama R 2006. Real-time imaging of the somite segmentation clock: revelation of unstable oscillators in the individual presomitic mesoderm cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 1313–1318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina G, Vogt A, Bakan A, Dai W, Queiroz de Oliveira P, Znosko W, Smithgall TE, Bahar I, Lazo JS, Day BW, et al. 2009. Zebrafish chemical screening reveals an inhibitor of Dusp6 that expands cardiac cell lineages. Nat Chem Biol 5: 680–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto M, Takahashi Y, Endo M, Saga Y 2005. The Mesp2 transcription factor establishes segmental borders by suppressing Notch activity. Nature 435: 354–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima Y, Kimura T, Suzuki C, Ohmiya Y 2004. Improved expression of novel red- and green-emitting luciferases of Phrixothrix railroad worms in mammalian cells. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 68: 948–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima Y, Yamazaki T, Nishii S, Noguchi T, Hoshino H, Niwa K, Viviani VR, Ohmiya Y 2010. Enhanced beetle luciferase for high-resolution bioluminescence imaging. PLoS ONE 5: e10011 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa Y, Masamizu Y, Liu T, Nakayama R, Deng CX, Kageyama R 2007. The initiation and propagation of Hes7 oscillation are cooperatively regulated by Fgf and notch signaling in the somite segmentation clock. Dev Cell 13: 298–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oginuma M, Niwa Y, Chapman DL, Saga Y 2008. Mesp2 and Tbx6 cooperatively create periodic patterns coupled with the clock machinery during mouse somitogenesis. Development 135: 2555–2562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oginuma M, Takahashi Y, Kitajima S, Kiso M, Kanno J, Kimura A, Saga Y 2010. The oscillation of Notch activation, but not its boundary, is required for somite border formation and rostral–caudal patterning within a somite. Development 137: 1515–1522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmeirim I, Henrique D, Ish-Horowicz D, Pourquié O 1997. Avian hairy gene expression identifies a molecular clock linked to vertebrate segmentation and somitogenesis. Cell 91: 639–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel-Kruse IH, Müller C, Oates AC 2007. Synchrony dynamics during initiation, failure, and rescue of the segmentation clock. Science 317: 1911–1915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saga Y, Hata N, Koseki H, Taketo MM 1997. Mesp2: a novel mouse gene expressed in the presegmented mesoderm and essential for segmentation initiation. Genes Dev 11: 1827–1839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada A, Shinya M, Jiang YJ, Kawakami A, Kuroiwa A, Takeda H 2001. Fgf/MAPK signaling is a crucial positional cue in somite boundary formation. Development 128: 4873–4880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serth K, Schuster-Gossler K, Cordes R, Gossler A 2003. Transcriptional oscillation of lunatic fringe is essential for somitogenesis. Genes Dev 17: 912–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima Y, Ohtsuka T, González A, Miyachi H, Kageyama R 2011. Intronic delay is essential for oscillatory expression in the segmentation clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 3300–3305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl MB, Deng C, Lewandoski M, Pourquié O 2007. FGF signaling acts upstream of the NOTCH and WNT signaling pathways to control segmentation clock oscillations in mouse somitogenesis. Development 134: 4033–4041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Gridley T 1998. Defects in somite formation in lunatic fringe-deficient mice. Nature 394: 374–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]