John Bostock (1772–1846) was an avid contributor to the Medical and Chirurgical Society's Medico-Chirurgical Transactions. His paper read to the Society on 16 March 1819 on summer catarrh was the first description of hay fever.

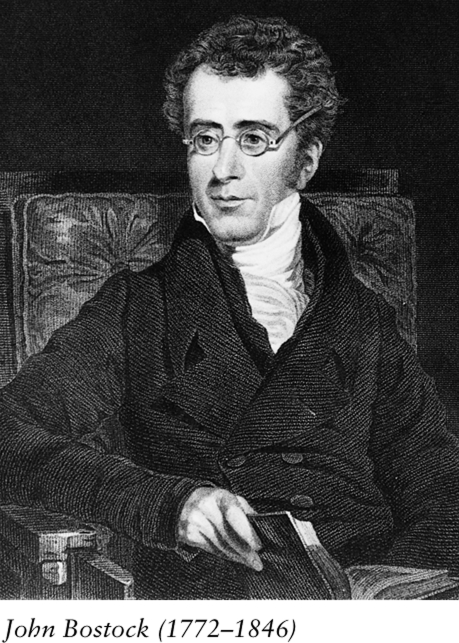

Bostock was born in Liverpool. His father, John Bostock, was also a physician. In 1792, the younger Bostock attended Joseph Priestley's course of lectures on chemistry at Hackney College in Middlesex. On his return to Liverpool he studied as an apothecary before going to study medicine in Edinburgh in 1794. At that time the joint professors of chemistry were Thomas Hope and Joseph Black, whose lectures he attended. Joseph Black had been William Cullen's pupil and successor and had discovered fixed air (i.e. carbon dioxide) and the principles of latent heat and specific heat. He was an engaging lecturer, and Bostock may have been strongly influenced by him. John Robison, in his preface to Black's lectures, published in 1803, wrote:

His personal appearance and manner were those of a gentleman, and peculiarly pleasing. His voice in lecturing was low but fine; and his articulation so distinct that he was perfectly well heard by an audience consisting of several hundreds. His discourse was so plain and perspicuous, his illustrations by experiment so apposite, that his sentiments on any subject never could be mistaken, even by the most illiterate; and his instructions were so clear of all hypothesis or conjecture, that the hearer rested on his conclusions with a confidence scarcely exceeded in matters of his own experience.

Bostock graduated MD in 1798, with a thesis on the secretion of bile, titled ‘Dissertatio physiologica inauguralis quædam de secretione in genere et præcipue de formatione fellis complectens’. He returned to Liverpool, where he became a physician to the General Dispensary. There he started to earn a reputation through his local activities, particularly his part in the foundation of the botanic gardens and the Fever Hospital, and his writings. In Remarks on the Nomenclature of the New London Pharmacopoeia (1810) he criticized the pharmacopoeia's terminology and proposed terminology based on structured chemical and botanical terms.

In 1817 Bostock gave up the practice of medicine and moved to London to further his scientific career. He became Lecturer in Chemistry at Guy's Hospital and later worked with Richard Bright and Thomas Addison. He studied the chemical composition of body fluids, especially urine in health and disease, and described how urea disappeared from the urine as it accumulated in the blood and how albumin appeared in the urine as it disappeared from the blood.

On 16 March 1819 Bostock presented an interesting case to the Medical and Chirurgical Society: ‘Case of a periodical affection of the eyes and chest’, the first recorded description of what he later called ‘catarrhus aestivus’ or summer catarrh, and which soon became known as hay fever.

The patient, whom Bostock identified as ‘JB’, was aged 46 and was ‘of a spare and rather delicate habit, but capable of considerable exertion, and has no hereditary or constitutional affection, except various stomach complaints, probably connected with, or depending upon, a tendency to gout’. From about the age of 8 and in about the beginning or middle of June each year JB suffered the following symptoms: a sensation of heat and fullness in the eyes, first along the edges of the lids, and especially in the inner angles, but after some time over the whole of the eyeball; a slight degree of redness in the eyes and a discharge of tears; worsening of this state until there was intense itching and smarting, inflammation, and discharge of a very copious thick mucous fluid. To these symptoms were added sneezing, tightness of the chest and difficulty in breathing, with irritation of the fauces and trachea.

He had had no relief from these symptoms by the use of bleeding, purging, blisters, spare diet, bark (i.e. quinine in Peruvian bark) and various other tonics, steel (i.e. medicinal iron), opium, mercury, cold bathing, digitalis, and a number of topical applications to the eyes. However, confining himself to the house reduced the symptoms. Bostock identified precipitating factors, including ‘a close moist heat, also a bright glare of light, dust or other substances touching the eyes, and any circumstance which increases the temperature’.

JB was of course Bostock himself. During the next nine years he collected another 28 cases or so, which he described in another communication to the Society, on 22 April 1828, in an article entitled ‘Of the catarrhus aestivus or summer catarrh’.

Bostock noted that this condition had not been previously described, except perhaps by William Heberden (1710–1801) in a passage that was brought to his attention by Dr M Hall: ‘I have known [catarrh] return in four or five persons annually in the months of April, May, June, or July, and last a month, with great violence’, a reference that may not be to hay fever at all. However, Bostock was unable to conclude that the disease was a new one and thought that it was merely a modification of ‘the common catarrh’. The term ‘catarrh’ was highly non-specific. From a Greek word, katarheein, meaning to run down, it referred to any profuse discharge from the nose and eyes, such as generally accompanies a cold. However, it could be qualified and its meaning changed. For example, ‘epidemic catarrh’ and ‘Russian catarrh’ were terms that were used to describe what we now call influenza, and ‘suffocative catarrh’ was another term for asthma. Nevertheless, it seems that Bostock thought that hay fever was just another form of what we might call a summer cold.

On the other hand, he was aware that there was a possible connection with grasses: ‘With respect to what is termed the exciting cause of the disease, since the attention of the public has been turned to the subject, an idea has very generally prevailed, that it is produced by the effluvium from new hay, and it has hence obtained the popular name of the hay fever’. All in all, the evidence does suggest that hay fever did not exist, or was at least very uncommon, before the 19th century; the presence of pollutants in the air after the start of the industrial revolution may have played a part in its emergence (see Ronald Finn in the Lancet 1992; 340: 1453–5).

Bostock wrote the first textbook of physiology in the English language, Elementary System of Physiology, in three volumes, during 1824–1827. He became a Council Member of the Royal Society in 1829 and its Vice-President in 1832, President of the Geological Society in 1826, and Treasurer of the Medico-Chirurgical Society of London. He also served on the Councils of the Linnean, Zoological, and Horticultural Societies and of the Royal Society of Literature. He died of cholera on 6 August 1846 at his London home, 22 Upper Bedford Place.

Eponyms associated with John Bostock

Bostock catarrh, Bostock disease: allergic rhinitis, hay fever

Selected bibliography by John Bostock

Essay on Respiration (1804)

Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia (1807)

Remarks on the Nomenclature of the New London Pharmacopoeia (1810)

An Account of the History and Present State of Galvanism (1818)

Elementary System of Physiology (three volumes) (1824–1827)

A Sketch of the History of Medicine from its Origin to the Commencement of the 19th Century (1835)

DECLARATIONS

Competing interests

None declared

Funding

None

Ethical approval

Not applicable

Guarantor

MR

Contributorship

Both authors contributed equally

Acknowledgements

This paper was originally published as Chapter 6 of Doctoring History by Manoj Ramachandran and Jeffrey K Aronson, published by the Royal Society of Medicine Press in 2010