Abstract

The purpose of this review is to identify knowledge about the influence of chronic disease on major life changing decisions (MLCDs). This review was carried out in three stages: identification of key search terms; selection of databases and searching parameters; and evaluation of references. Only two articles matched the main search term ‘major life changing decisions’. No article reviewed or measured the influence of chronic disease on major life changing decisions. However, 76 articles and various sections of seven books were identified that provided insight into this area and these are reviewed in detail. This literature review has brought together previously scattered information on chronic disease impact on important patient life decisions. These include decisions related to having children, marriage and divorce, job and career choice, social life, holidays, travelling and education. Lifestyle decisions viewed by patients as major decisions are also documented. The influence of cancer on life decisions is discussed, as are affected life decisions of other family members. Very little information is available about the long-term impact of chronic disease on patients' lives and methodology to assess long-term impact is incomplete. This review points to a novel dimension to health-related outcome research, the impact of chronic disease on major life changing decisions, and its possible implication for patients' future health.

Introduction

The health sciences literature is replete with information related to the current impact of different diseases on patients' quality of life (QoL) and is mainly focused on the traditional health-related quality of life (HRQoL) domains (physical, social and psychological). In contrast, very little is known about the long-term impact of chronic diseases on patients' lives, for example the influence of chronic diseases on major life changing decisions (MLCDs) such as in relation to career choice, having children, marriage, divorce, early retirement and moving abroad. Through this literature review we introduce and explore this new concept and highlight its importance in a patient-centred healthcare system.

Methods

The search strategy was carefully formulated to retrieve appropriate publications and to reduce the chances of missing important relevant information. It involved three stages:

Stage 1: Identification of key search terms – The key search terms were selected to gain a broad perspective and to ensure a wide coverage of the literature. The terms included life changing decision, long-term impact and QoL. The main key term ‘life changing decisions’ was combined with: influence, chronic disease, family, decisions and over time (Table 1).

Stage 2: Selection of databases and searching parameters – OvidSP MEDLINE(R) database was selected for the initial comprehensive literature search. Searching limits were kept general in order to get more information from a broader perspective. The search was limited to original articles, and abstracts published in English. A separate questionnaire and item search was also carried out of the ‘Compendium of Quality of Life instruments’.1,2 Data resources searched are listed in Table 2.

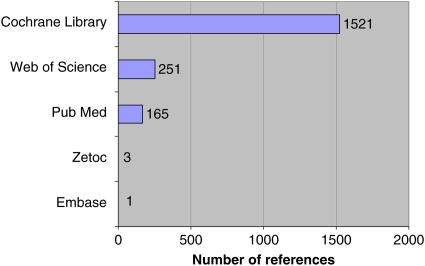

Stage 3: Searching results and evaluation of references – A review of published studies and articles was conducted. The aim and methodology of each study given in the abstract of the article identified was read to determine its relevance. Articles were then retrieved from the main database. A total of 4251 articles were retrieved from the OvidSP MEDLINE (R) database for close inspection to identify any study with potential relevance to our research concept. Articles were obtained with a number of combinations of different selected key terms such as ‘life changing decisions’ and ‘patient decisions’ (Table 1). A total of 3397 articles were identified from a separate search using a combination of quality of life and different descriptors of studies such as prospective study, long-term study, qualitative study, longitudinal study, cohort study and follow-up study. When the term ‘life changing decisions’ was entered in the Cardiff University Metalib resources (Figure 1) 1941 articles were retrieved. Only two articles matched the exact term ‘major life changing decisions’.

Table 1.

Search results of different individual and combined terms

| Single or combined terms used in searches | Retrieved references (n) |

|---|---|

| Life changing decisions | 2 |

| Patient decisions | 93 |

| Personal decisions | 45 |

| Family decisions | 52 |

| Change in lifestyle | 115 |

| Patient fear | 95 |

| Patient opinions | 73 |

| Patient suggestions | 12 |

| Patient views | 133 |

| Patient recommendations | 39 |

| Patient experiences | 480 |

| Patient account | 249 |

| Patient perceptions | 711 |

| Patient feelings | 19 |

| Patient adaptations | 1 |

| Patient diary | 93 |

| Influence on Quality of Life | 368 |

| Long illness | 44 |

| Living with disease | 95 |

| Coping with disease | 74 |

| Quality of Life over time | 70 |

| Long-term impact | 1255 |

| Quality of Life, long-term impact and disease: combined search | 60 |

| Disease, influence, impact, family and decisions: combined search | 73 |

Table 2.

List of data resources searched

| 1. Ovid Medline |

| 2. Google Scholar |

| 3. Cardiff University electronic journals portal |

| 4. Cardiff University Electronic Metalib resources: Cochrane Library (Wiley), Embase, Excerpta Medica (Ovid), PubMed, Web of Science, Zetoc |

Figure 1.

Metalib resources result for the term ‘life changing decisions’

Quality of Life instruments search

An extensive search was carried out in the ‘Compendium of Quality of Life instruments’.1,2 This compendium describes over 150 questionnaires, profiles and inventories and covers general, disease specific, group specific and economic specific instruments. The purpose of the compendium search was to investigate in detail whether any questionnaire, profile or inventory has included the term ‘life changing decision’ for the assessment of disease impact on patients' lives. The search did not reveal any questionnaire, profile or inventory that has included any item, domain, indicator or descriptor to cover the impact of illness on important life changing decisions.

Results

In the literature search, only two articles matched the term ‘major life changing decisions’. These were related to psychology3 and to neuroeconomics.4 In the first article Bauer et al.3 examined the personal stories of life changing decisions in relation to personality and wellbeing and discussed the concepts of ‘crystallization of desire (approaching to a desired future) and crystallization of discontent (escaping an undesired past)’. In the second article Berns et al.4 explained life changing decisions as an example of intertemporal choice. Intertemporal choice is a study of preferences, value allocation and decisions with consequences that play out over time. Life changing decisions related to education, marriage, fertility and how much food to eat, spending, investment, relationships and crime are some examples of intertemporal choices which contain trade-offs. Both studies were unrelated to the concept of health and life decisions.

Health and major life changing decisions

Life is about choices and decisions play an important role. Life choices may become limited and undesirable due to negative stressful life events, and in this situation any decision could be life changing. The diagnosis of a chronic disease is a negative life changing event in physical, psychological and social terms5, 6 and the initial news of a life-threatening condition is often devastating for patients7. King et al.8 suggested that ‘Major life changes, by definition, require individuals to come to terms with a new set of life circumstances. Some life changes involve irrevocable alterations in our lives, requiring us to redefine the very meaning of our existence, to seek out new sources of purpose, and to reassess our priorities.’ The diagnosis or onset of disease, however, is not a decision that a patient takes. Very little information is available about what constitutes a major life changing decision or how chronic disease can influence life changing decisions.

What can we learn from the available literature?

Our extensive review has not revealed any specific research evaluating health-related life changing decisions. Several studies9–14 referred to disease as ‘life changing’ or as a ‘major life changing event or experience’ but remained focused on disease evaluation, treatment, patient education and quality of life. A few studies described how chronic disease might impact on important life decisions.

Having children

Reproductive choices are very important life decisions and disease may influence an individuals' choice to have children. Kadir et al.15 suggested that the decision to have children is a complex one, even in the absence of disease. They conducted a survey of women with haemophilia to assess their experiences in pregnancy and their attitudes towards their reproductive choices. They found that age and emotional, social and financial factors were the main influences in planning pregnancy. Twenty-two of 160 women reported that the decision about their first pregnancy, and 13 of 132 women reported that the decision about subsequent pregnancies was influenced by counselling and the results of prenatal diagnostic tests. The following question was also asked to all women, whether they had ‘ever made a conscious decision not to have children/any more children’. Fifty-four percent of women reported that having haemophilia was a major factor in this decision; 44% of women did not want to transfer haemophilia to their child, 6% had previous experience of haemophilia in the family, and 27% reported personal, social, financial and medical reasons for this decision.15 This questionnaire survey revealed individuals' priorities in different life situations, such as the prime example of disease influence on having children. Various studies suggest that the decision to have genetic testing could be a life changing decision and may impact on family planning, interpersonal relationships, social, financial and employment aspects.16–18 The decisions of parents about how to proceed after the antenatal diagnosis of congenital problems is important and difficult to make, as the decision may change their lives forever.19

Breast cancer is a life-threatening condition and deciding to have children after breast cancer is an important life changing decision for mothers. In 1994, Dow20 carried out a study to identify the reasons why young women decided to become pregnant after breast cancer, to describe helpful behaviours in decision-making and to explore the meaning of having children after breast cancer. In this qualitative research, 16 women took part in semi-structured interviews. The participants were interviewed after breast cancer treatment and were asked to share their experiences following an open-ended question about breast cancer and subsequent pregnancy. Three main themes were identified that influenced having children after breast cancer treatment: having children as a cherished goal; a desire for sense of normalcy; and reconnection with others. Participants expressed a range of concerns about pregnancy (having a normal pregnancy, having a healthy infant, disease recurrence and concerns related to breastfeeding) and having children (recurrence and death, being hypervigilant, restructured living one day at a time, maternal concern). This research also highlighted in some patients that a longstanding desire for having children was interrupted by the diagnosis of breast cancer. Before the diagnosis, breast cancer participants were in control; however, after breast cancer, they lost control of their lives. The behaviour of their spouse and family, healthcare providers and other breast cancer survivors were identified as critical factors in decision-making.20 These findings suggest that a patient's personal efforts, professional help and the process of sharing experiences could be helpful to the person making life changing decisions influenced by a recent health event. This area was also discussed in another study, where newly diagnosed patients with HIV chose not to become pregnant.21

Anderson and Martin22 presented the narratives of one couple (a cancer survivor and her husband), who lived through the life changing events following a cancer diagnosis. The narratives are very moving and give insight into how a chronic life-threatening condition can change a patient's life. It is also evident that after the diagnosis, the patient's priorities changed and was preparing herself for the future. It is not clear whether the patient took any life changing decision, but words used by the patient in her story, such as ‘I thought I was dying’, ‘I had no control over what was happening to me’, ‘I was still worried about my future’ and ‘It was dehumanizing and very lonely’ indicate that the disease and its treatment have a physical impact and result in emotional fluctuation, fear and uncertainty which may influence a patient's priorities in life and may also change their family and social role and identity.

Marriage and divorce

Physical health and marital dissatisfaction have a direct effect on each other.23 Health, mental wellbeing and its associations with marriage, relationships and family have been widely discussed in the literature, and any change in circumstances due to health may impact on the quality of life of family members and relationships. For example, if poor health causes a break-up in a relationship then divorce (as a stressful life event) may lead to poor health.24–27 Wilson and Waddoups28 carried out a study to investigate how health impacts on the breakup of a marriage. Data were used from the four 2-year periods of the Health and Retirement Study (1992, 1994, 1996 and 1998). In 1992, 4241 couples aged 51–61 years entered into this study. The health mismatch hypothesis was tested by using different spousal health combinations and separation was used as an indicator of marital dissolution. Marital dissolution was not observed from a life course perspective or from the perspective of health influence on separation. However, the study still suggests that the poor health of a spouse at a young age may cause marriage break-up over time. There is information concerning the impact of disease on marriage, marital adjustment and marital quality;29–32 however, it is not clear whether chronic disease influenced patients' decisions to get married or prevented them becoming involved in any relationship.

Seidler and Kimball33 suggest that patients with chronic skin disease may learn to cope over time but their important decisions early in life may have long-lasting impact on their quality of life. Seidler and Kimball used the Research Patient Data Repository (RPDR) database and cross-sectional analysis to determine any link between key ages or age ranges and social disconnection. Religious non-affiliation (for loss of social network), divorce (for loss of interpersonal connection) and use of Medicaid (for disconnection in the work place) were used as surrogate evaluative measures for the assessment of social connectivity among psoriasis patients. They found that divorce rates in psoriasis patients were higher in the age groups 29–31 years (1.3% vs. 1.7%; P < 0.05) and 32–34 years (2.3% vs. 1.1%; P < 0.001) than corresponding rates in the general population. Seidler and Kimball33 highlighted the importance of the association of disease and age groups with the important life decision to divorce, but it is not clear whether psoriasis specifically had an influence on the patients' decision to get divorced or whether psoriasis contributed to the partners' decision to get divorced.

Chronic disease can also influence the major life changing decisions of other family members. In a cross-sectional study Fine et al.34 asked a series of questions to parents of children suffering from inherited epidermolysis bullosa (EB) about the long-term impact of their child's illness on their marital life; 54–64% parents of children with dominant dystrophic EB (DDEB) and recessive dystrophic EB (RDEB) reported that they had decided not to have additional children; 88% of divorced couples with children affected by junctional EB (JEB), 50% of divorced couples with children affected by DDEB and 67% of divorced couples with children affected by RDEB reported that their child's disease was a major factor leading to their decision to divorce.

Job and career choice

In a 1-year follow-up study, Cvetkovski et al.35 concluded that occupational hand eczema in later life is associated with poor quality of life and lower socioeconomic status and results in patients taking prolonged sick leave, becoming unemployed or changing their job. One year is a relatively short period for follow-up to assess these changes, but in this study 50% of patients had changed their jobs during the 12 months, which suggests how chronic illness can change life significantly. The frequency of reported change of job due to hand eczema was higher than when previously assessed by Meding et al.36 in their 15 year follow-up study (1983–1998). They had found that 20 (3%) out of 706 patients from different employment backgrounds (medical and nursing work, cleaners, hairdressers, kitchen workers, painters and mechanics) reported change in their occupations because of their hand eczema, and 15 patients reported improvement after change in occupation. Eight percent of patients had reported change in their occupation before the initial 1983 examination. In terms of job change, both studies focused on occupational risk and did not discuss the nature or the consequences of the decision involved in relation to change in employment. It is obvious from both studies that chronic disease can influence a patient's decision related to selection of jobs or to change in occupation. Long-term illness can make it difficult for patients to remain in the same employment if their occupation is one of the major reasons for health deterioration. Choices become limited for patients and in some cases a change of job might result in financial loss. Patients might remain in the same employment and suffer because of socioeconomic reasons (family, better housing and children's education).

The effects of eczema ‘over the last few years’ on patients' quality of life were assessed in 92 eczema patients.37 Eighty percent of the patients reported effects on their family life. Working patients lost around £5000 (median estimated) over the previous year. Other impacts identified were effects on sexual relationships (57%), effects on choice of career (51%) and 52% reported effects on long-term personal friendships and relationships.37

In another study, Malcomson et al.38 conducted two qualitative focus group discussions to explore the impact of multiple sclerosis (MS) (n = 13, age 40–67 years, mean disease duration = 17 years) on patients' lives. Several patients reported changes to their employment circumstances along with other disease-related impacts (interpersonal and social life, stress, unpredictability, fear and impact on daily living). Despite the resulting loss in socioeconomic status, one patient made a decision to change from full-time to part-time employment and two patients gave up their paid jobs because of the impact (fatigue, lack of energy, decreased mobility and stress) of MS on their lives. The patients indicated that MS influenced their important decisions regarding employment and made them compromise (an undesirable objective) in the best way possible to accommodate their health needs and also take control of their resulting lifestyle changes.

Social life, holidays, travelling and education

Arnold et al.39 conducted six focus group (n = 48) discussions with women suffering from fibromyalgia to assess its impact on their lives. Participants raised a variety of disease-related (cognitive impairment, emotional, functional and quality of life impact) and symptom-related (pain, fatigue and sleep) issues. Socially, fibromyalgia patients feel that due to the unpredictable nature of the disease, they are unable to plan any event and are judged by co-workers and friends as unreliable, resulting in loss of friendship and their withdrawal from social engagements. The participants also reported that they failed to properly look after their own children and families. Not being able to go for family trips was reported as life changing by patients and lack of participation in household activities and decreased sexual intimacy had caused great strain on their personal relationships. This study indicated that not to take part in simple things, such as social activities, is viewed by some people as a life changing decision. Those affected might still take part in different activities but embarrassment and humiliation and the long-term nature of the disease might drag them towards complete isolation. Similarly, the constant strain of disease on personal relationships may lead to taking more serious life decisions, such as separation or divorce. The participants also reported that their disease not only made them change their job frequently but made them reduce their working hours. Half of the patients left their jobs because of their illness, which ultimately resulted in financial difficulties. Some patients reported that their conditions stopped them from pursuing higher education; this is a very difficult life decision to take with resulting consequences in some circumstances of low paid menial hard work and further health deterioration.39 Such patients may need more support and appropriate advice at those life stages when they have to take important life decisions regarding employment and education. Increased patient understanding seems necessary to reduce the inappropriate impact of the disease on decisions which determine the future course of life.

Lifestyle decisions as major life changing decisions

Life decisions and their perceived value are subjective in nature. Some decisions perceived as major by some patients may seem very minor to an observer and more related to day-to-day activities/choices. However, individuals' specific circumstances, such as experiencing the onset of chronic disease, could make these daily decisions and choices more important for that individual and life changing. Huggins et al.40 surveyed young patients suffering from hydroa vacciniforme and suggested that both the type of chronic condition and the duration of disease (median age at onset 7 years) influenced the impact on quality of life. Concerning the Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) responses, 63.6% patients (n = 11, age 9–17 years) reported impact on going out, playing and hobbies, 54.5% reported impact on choice of clothing, and 36.4% reported impact on swimming and sports activities. On their Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) responses 75% adult patients (n = 4, age ≥18 years and over) reported that their skin condition influenced their choice of clothing. It is understandable that disease-related aesthetic reasons and embarrassment (50%) could play an important part in influencing patients to view simple decisions such as choice of clothing or swimming as ‘major decisions’ as they involve change in their lifestyle and image, which patients may feel to be wrongly perceived by others. In another study Hon et al.41 found that young girls with atopic dermatitis had more problems concerning clothes or shoes than boys, indicating the importance of gender on disease influence on specific aspects of patients' lives. Decisions about lifestyle, for example smoking, drinking and over-eating, may have serious consequences on health.42 Any decision to modify these habits may determine an individual's future health, reflecting the significance of lifestyle-related decisions. Similarly, other health-related decisions such as the decision over choice of treatment (whether surgery or medication) could be life changing for a patient.43–45

Are the long-term impacts of diseases being measured?

It is important to understand the long-term impacts of a chronic disease as these impacts may change over time. Understanding long-term impacts may assist clinicians in developing better management plans for patients.

Several studies have assessed the quality of life impact experienced by patients who had suffered from chronic diseases for a long period of time.46–54 However, these studies predominantly assessed current experiences and were not specifically designed to assess the long-term impact. Similarly, in follow-up studies the assessment of disease impact mainly compares current impacts, and the changes which have occurred in the level of current impact over a period of time.55–62 This may not reflect the different type of impacts that the patient has experienced over the intervening years. To record the true long-term impact, it would be necessary to ask patients how their illness has affected them over the full period of their illness. Such a holistic exploratory retrospective approach could provide a new insight into the nature of the long-term impacts faced by patients during different stages of their life including newly affected domains, such as health-related major life changing decisions.

Discussion

Some negative life events (e.g. chronic illness, accident, injury) may influence major life decisions such as marriage, divorce, job, education, having children, moving abroad, moving house and retirement. For example, a diagnosis of chronic illness may influence an important life decision related to employment, such as whether to carry on in full-time work or take a part-time job or retire early, which might be a good option from the perspective of health. Such a decision might seem simple but in fact may be very difficult to make because the consequences of the decision may result in financial difficulties, which may lead to other problems related to the patient's mortgage, lifestyle, family and relationships. This knock-on effect may lead to further health deterioration. Although studies included in this review were not designed to capture the influence of chronic diseases on major life changing decisions, some of their findings aid our understanding of this novel aspect of health-outcome research.

Kimball et al.63 reviewed the long-term impact of psoriasis and proposed the concept of ‘Cumulative Life Course Impairment’ (CLCI). This concept results from an interaction between ‘(a) the burden of stigmatization and physical and psychological co-morbidities and (b) coping strategies and external factors’.63 The concept of CLCI as described63 does not specifically address the impact of psoriasis on major life changing decisions. However, if a major life changing decision is influenced by psoriasis, this is likely to contribute to CLCI,64 and indeed it may be that influences on major life changing decision are of equal or greater importance than stigmatization and coping strategies in contributing to CLCI.

In other words, one negative life event, such as onset of a chronic disease, may influence decisions relating to several subsequent life events, such as choice over education, career, employment, marriage, housing, having children and moving abroad.

It is obvious that the life decisions that a patient makes are normally intended to gain the desirable outcome of a better life. However, not every life decision turns out to be a positive or a correct decision. After the diagnosis of a chronic or life-threatening condition, acceptance is usually a great challenge for patients. Patients search all available avenues for a cure and may take a considerable time to realize that they might have to live with the condition for the rest of their lives. A change in attitude to acceptance may give a patient motivation for the future but life changing decisions and related choices may remain very limited due to the ongoing illness and other health-related factors, such as severity, depression or treatment. Therefore, the desired future outcome may not be as successful as it would be in disease-free individuals. Decisions at the right time about higher education and early career development or having children are important as part of the natural course of life and occur at different life stages, but the continuous long-term impact of chronic disease on patients' lives may influence these decisions. Patients might either decide differently or might delay their decision. This is where health providers and clinicians may play a very important role to warn patients at an early stage about the long-term consequences of chronic disease, which in turn not only might minimize the disease impact on patients lives, particularly on major life changing decisions, but also reduce the burden on the health system.

Conclusion

There is little specific information in the literature about the impact of chronic diseases on major life changing decisions. There is no defined measure to capture this vital information. Up to now the assessment of the long-term impacts of a disease has been based on the repeated evaluation of its current impacts on patients' lives, thereby, potentially missing major aspects of the impact. Important specific questions remain unanswered: what is the definition of a ‘major life changing decision’? How do patients take their life changing decisions while suffering from long-term health problems? To what extent do chronic diseases influence major life changing decisions? What influential factors are involved in life changing decision-making? How capable are patients to take appropriate life changing decisions? There is a need for strategies for healthcare providers to assist patients to take appropriate decisions and allow them to maximize their control over their lives.

The lack of knowledge in this area revealed by this review suggests new areas for research. In addition to both follow-up and prospective research techniques, exploratory retrospective research methodology is essential to understand the magnitude of the influence of chronic diseases on life changing decisions. This review has highlighted a novel dimension to health-related outcome research, the new domain of ‘major life changing decisions’. Encompassing this concept may make health-related quality of life estimation closer to reality. There is a need for multidisciplinary research to capture fundamental information for further conceptualization, to determine the definition of health-associated major life changing decisions, to create a suitable instrument for its measurement, to assess the feasibility of this new concept as a new measurable dimension and to assess its possible implications on patients' lives and on healthcare resources.

DECLARATIONS

Competing interests

AYF is joint copyright owner of the DLQI and CDLQI

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Centre for Socioeconomic Research, School of Pharmacy and the Department of Dermatology and Wound Healing, Cardiff University

Ethical approval

Not applicable

Guarantor

ZB

Contributorship

ZB wrote the initial draft; SS and AYF contributed extensively to its critical revisions and re-drafting

Acknowledgements

None

References

- 1.Salek MS Compendium of Quality of Life Instruments. Volumes 1–5. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salek MS Compendium of Quality of Life Instruments. Volumes 6–7. Haslemere: Euromed Communications, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer JJ, McAdams DP, Sakaeda AR Crystallization of desire and crystallization of discontent in narratives of life changing decisions. J Pers 2005;73:1181–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berns GS, Laibson D, Loewenstein G Intertemporal choice-toward an integrative framework. Trends Cogn Sci 2007;11:482–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnack JL, Chrisler JC The experience of chronic illness in women: a comparison between women with endometriosis and women with chronic migraine headaches. Women Health 2007;46:115–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nussbaum JF, Baringer D, Kundrat A Health, communication,, aging: cancer, older adults. Health Commun 2003;15:185–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevens PE, Hildebrandt E Life changing words: Women's responses to being diagnosed with HIV Infection. Adv Nurs Sci 2006;29:207–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King LA, Scollon CK, Ramsey C Stories of life transition: Subjective well-being and ego development in parents of children with Down syndrome. J Res Pers 2000;34:509–36 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller NC, Askew AE Tibia fracture. An overview of evaluation and treatment. Orthop Nurs 2007;26:216–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher GS, Emerson L, Firpo C, Ptak J, Wonn J, Bartolacci G Chronic pain and occupation: an exploration of the lived experience. Am J Occup Ther 2007;61:290–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher MA, Taylor GW, Shelton BJ, Debanne SM Sociodemographic characteristics and diabetes predict invalid self-reported non-smoking in a population-based study of U.S. adults. BMC Public Health 2007;7:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith M Efficacy of specialist versus non-specialist management of spinal cord injury within the UK. Spinal Cord 2002;40:6–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson-Smith G Prayer after stroke. Its relationships to quality of life. J Holist Nurs 2002;20:352–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cassidy B, Clarke A, Shahtahmasebi S Quality of life: information and learning resources in supporting people with severe life changing injuries to return to independence. Scientific World Journal 2004;4:536–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kadir RA, Sabin CA, Goldman E, Pollard D, Economides DL, Lee CA Reproductive choices of women in families with haemophilia. Haemophilia 2000;6:33–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith CO, Lipe HP, Bird TD Impact of presymptomatic genetic testing for hereditary ataxia and neuromuscular disorders. Arch Neurol 2004;61:875–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cameron LD, Muller C Psychosocial aspects of genetic testing. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2009;22:218–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim J, Macluran M, Price M, Bennett B, Butow P Short and long-term impact of receiving genetic mutation results in women at increased risk for hereditary breast cancer. J Genet Couns 2004;13:115–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rempel GR, Cender LM, Lynam MJ, Sandor GG, Farquharson D Parents' perspectives on decision making after antenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal 2004;33:64–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dow KH Having children after breast cancer. Cancer Pract 1994;2:407–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craft SM, Delaney RO, Bautista DT, Serovich JM Pregnancy decisions among women with HIV. AIDS Behav 2007;11:927–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson JO, Martin PG Narratives and healing: Exploring one family's stories of cancer survivorship. Health Commun 2003;15:133–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ganong LH, Coleman M Remarriage and health. Res Nurs Health 1991;14:205–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gove WR, Hughes M, Style CB Does marriage have a positive effect on the psychological well-being of the individual? J Health Soc Behav 1983;24:122–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rose CE, Mirowsky J, Goldsteen K The impact of the family on health: The decade in review. J Marriage Fam 1990;52:1059–78 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Renne KS Health and marital experience in an urban population. : DeBurger JE, Marriage today: Problems, issues, and alternatives. New York, NY: Shenkman, 1977:304–31 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albrecht SL, Babr HM, Goodman KL Divorce and Remarriage: Problems, Adaptations, and Adjustment. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson SE, Waddoups SL Good marriages gone bad: Health mismatches as a cause of later-life marital dissolution. Popul Res Policy Rev 2002;21:505–33 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burman B, Margolin G Analysis of the association between marital relationships and health problems: an interactional perspective. Psychol Bull 1992;112:39–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roth-Roemer S, Kurpius SER Beyond marital status: an examination of marital quality and well-being among women with rheumatoid arthritis. Womens Health 1996;2:195–205 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodwins SS The marital relationship and health in women with chronic fatigue and immune dysfunction syndrome: views of wives and husbands. Nurs Res 1997;46:138–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cannon CA, Cavanaugh JC, Delaware U Chronic illness in the context of marriage: a systems perspective of stress and coping in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Fam Syst Health 1998;16:401–18 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seidler EM, Kimball AB Socioeconomic disability in psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2009;161:1410–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fine JD, Johnson LB, Weiner M, Suchindran C Impact of inherited epidermolysis bullosa on parental interpersonal relationships, marital status and family size. Br J Dermatol 2005;152:1009–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cvetkovski RS, Zachariae R, Jensen H, Olsen J, Johansen JD, Agner T Prognosis of occupational hand eczema: a follow-up study. Arch Dermatol 2006;142:305–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meding B, Wrangsjo K, Järvholm B Fifteen-year follow-up of hand eczema: persistence and consequences. Br J Dermatol 2005;152:975–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Finlay AY Measures of the effect of adult severe atopic eczema on quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1996;7:149–54 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malcomson KS, Lowe-Strong AS, Dunwoody L What can we learn from the personal insights of individuals living and coping with multiple sclerosis? Disabil Rehabil 2008;30:662–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arnold LM, Crofford LJ, Mease PJ, et al. Patient perspective on the impact of fibromyalgia. Patient Educ Couns 2008;73:114–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huggins RH, Leithauser LA, Eide MJ, Hexsel CL, Jacobsen G, Lim HW Quality of life assessment and disease experience of patient members of a web-based hydroa vacciniforme support group. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2009;25:209–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hon KLE, Leung TF, Wong KY, Chow CM, Chuh A, Ng PC Does age or gender influence quality of life in children with atopic dermatitis? Clin Exp Dermatol 2008;33:705–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wright P, Belt S, John C Helping people assess the health risks from lifestyle choices: Comparing a computer decision aid with customized printed alternative. Commun Med 2004;1:183–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mastaglia B, Kristjanson LJ Factors influencing women's decisions for choice of surgery for stage-I and stage-II breast cancer in Western Australia. J Adv Nurs 2001;35:836–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McHugh GA, Luker KA Influence on individuals with osteoarthritis in deciding to undergo a hip or knee joint replacement: A qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil 2009;31:1257–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Warren RB, Griffiths CEM Systemic therapies for psoriasis: methotrexate, retinoids, and cyclosporine. Clin Dermatol 2008;26:438–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Finlay AY, Coles EC The effect of severe psoriasis on the quality of life of 369 patients. Br J Dermatol 1995;132:236–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, Fleischer AB, Reboussin DM Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999;41:401–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krueger G, Koo J, Lebwohl M, Menter A, Stern RS, Rolstad T The Impact of Psoriasis on Quality of Life: Result of a 1998 National Psoriasis Foundation Patient-Membership Survey. Arch Dermatol 2001;137:280–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zachariae R, Zachariae H, Blomqvist K, et al. Self reported stress reactivity and psoriasis-related stress of Nordic psoriasis sufferers. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2004;18:27–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alonso J, Ferrer M, Gandek B, et al. Health-related Quality of Life associated with chronic conditions in eight countries: results from the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. Qual Life Res 2004;13:283–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ampon RD, Williamson M, Correll PK, Marks GB Impact of asthma on self-reported health status and Quality of Life: a population based study of Australians aged 18–64 Thorax 2005;60: 735–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saarni SL, Harkanen T, Sintonen H, et al. The impact of 29 chronic conditions on health-related Quality of Life: A general population survey in Finland using 15D and EQ-5D. Qual Life Res 2006;15:1403–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barnett M Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a phenomenological study of patients' experiences J Clin Nurs 2005;14:805–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hagren B, Pettersen IM, Severinsson E, Lutzen K, Clyne N Maintenance haemodialysis: patients' experiences of their life situation. J Clin Nurs 2005;14:294–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Husser EK, Roberto KA Older women with cardiovascular disease: perception of initial experience and long-term influences on daily life. J Women Aging 2009;21:3–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saha SK, Khan NZ, Ahmed AS, et al. Neurodevelopmental sequelae in pneumococcal meningitis in Bangladesh: a comprehensive follow-up study. Clin Infect Dis 2009;48:S90–S96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuriya B, Gladman DD, Ibanez D, Urowitz MB Quality of Life over time in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:181–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen H, Cohen P, Kasen S, Johnson JG, Berenson K, Gordon K Impact of adolescent mental disorders and physical illnesses on Quality of Life 17 years later. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006;160:93–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sillanpaa M, Haataja L, Shinnar S Perceived impact of childhood-onset epilepsy on Quality of Life as an adult. Epilepsia 2004;45:971–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huurre TM, Aro HM Long-term psychosocial effects of persistent chronic illness. A follow-up study of Finnish adolescents aged 16 to 32 years. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002;11:85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heald AH, Ghosh S, Bray S, et al. Long-term negative impact on quality of life in patients with successfully treated Cushing's disease. Clin Endocrinol 2004;61:458–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beattie PE, Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH, Ferguson J Characteristics and prognosis of idiopathic solar urticaria. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:1149–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kimball AB, Gieler U, Linder D, Sampogna F, Warren RB, Augustin M Psoriasis: is the impairment to a patient's life cumulative? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010;24:989–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bhatti ZU, Salek MS, Finlay AY Major Life Changing Decisions and Cumulative Life Course Impairment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011;25:245–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]