Abstract

Evaluating interventions that reduce HIV stigma may help to craft effective stigma-reduction programs. This study evaluates the effects of a community popular opinion leader HIV/STI intervention on stigma in urban, coastal Peru. Mixed effects modeling was used to analyze data on 3,049 participants from the Peru site of the NIHM collaborative trial. Analyses looked at differences between the comparison and intervention groups on a stigma index from baseline to 12- and 24-month follow-up. Sub-analyses were conducted on heterosexual-identified men (esquineros), homosexual-identified men (homosexuales), and socially marginalized women (movidas). Compared to participants in the comparison group, intervention participants reported lower levels of stigma at 12- and 24-month follow-up. Similar results were found within esquineros and homosexuales. No significant differences were found within movidas. Findings suggest that interventions designed to normalize HIV prevention behaviors and HIV communication can reduce HIV-related stigma and change community norms.

Keywords: Stigma, HIV prevention, Popular opinion leader intervention, Peru

Introduction

HIV-related stigma can reduce people’s willingness to engage in HIV prevention, testing, and treatment [1, 2]. Stigma has been associated with decreases in HIV prevention behaviors, including attendance of HIV-related educational meetings and counseling sessions [3], preventive or risk reduction sexual behaviors [2], and participation in programs to prevent mother-to-child transmission [4, 5]. Stigma has also been linked to a reduction in quality of life among people with HIV [6–8]. For example, the discovery of a positive test result may lead to the loss of family ties, friendship, employment and housing, dismissal from school, denial of health/life insurance and health care, and being perceived as an immoral individual [8–13]. Over the more than two decades that the HIV epidemic has spread, we have been able to make advancements in knowledge about HIV prevention and transmission, epidemiology, and treatment. However, HIV-related stigma continues to be a serious problem and negatively impact the lives of both infected and uninfected individuals [14, 15].

Longitudinal interventions designed to change behavioral norms and tailored to cultural and situational differences may reduce stigma [16, 17]. Attempts to reduce HIV-related stigma have primarily focused on changing health providers’ or the general population’s perceptions about HIV to increase understanding about people living with HIV. For example, Brown et al. found that stigma can be reduced through the following intervention aims: providing students with information about HIV through advertisements and lectures, providing counseling and support groups to praise positive attitudes about HIV, increasing contact between health providers and people infected with HIV, and through psychological techniques such as imagery and hypothetical contact with people with HIV [17]. While many of these interventions appear to decrease stigma, they were conducted on small populations and could not assess whether these effects endure over time. Interventions designed to normalize HIV prevention behaviors and increase conversations about HIV prevention might also be effective in reducing stigma. Further, tailoring an intervention to a specific culture, region, and social class may improve the success of an intervention in reducing HIV-related stigma [18, 19].

HIV stigma is particularly high is Peru, making it an important area of focus for reducing stigma [20, 21]. Rates of HIV have been increasing in Peru, especially among men who have sex with men (MSM), and reducing stigma may help to improve testing and prevention adherence [22]. Recent research in Peru has focused on three stigmatized groups at disproportionately high risk for sexually transmitted infection: heterosexual-identified men who are permanently or temporarily unemployed (esquineros), homosexual-identified men (homosexuales), and socially marginalized women who are often single mothers who spend time, drink alcohol and have sex with socially marginalized men (movidas) [23–26]. Reducing HIV-related stigma in these groups and within the general Peruvian populations could potentially increase HIV testing, prevention and treatment [27].

The following study looks at the effects of an intervention designed to increase HIV prevention messages and conversations about HIV to improve rates of HIV testing and decrease sexual risk behaviors in Peru. This analysis focuses on the intervention’s effect on HIV-related stigma.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Participants were from the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial [28]. The 2-year trial was based on the theory of diffusion of innovations [29] and involved recruiting and training popular, well-respected individuals to deliver HIV/STD prevention messages to their peers within the context of casual conversations.

The study included 20 barrios, or neighborhoods, that were matched on sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevalence based on overall STI prevalence and randomized to intervention or comparison condition. The sample included Peruvian men and women (i.e., esquineros, homosexuales, and movidas) aged 18–40 years old from Lima, Chiclayo, and Trujillo, who frequented social venues in their barrios at least twice a week. In the 10 barrios randomized to the intervention, peer-nominated leaders from within the esquinero, movida, and homosexual populations were recruited and trained as community popular opinion leaders (CPOLs). Individuals nominated by their peers were approached and trained as CPOLs. CPOLs were people who were part of the three populations of interest (esquineros, movidas, and homosexuales) and were recruited with equal percentages of CPOLs in each of the three groups. CPOLs were men and women who lived within these populations and were well respected by others in the community so that others would listen to their advice. CPOLs underwent four training sessions over a one-month period prior to the implementation of the trial in the field, included role playing, education regarding HIV and STI transmission and risk, and skills training regarding how to deliver messages of prevention to their peers. Once in the field they were tasked with delivering prevention messages to their peers at the venues of social interaction were they were recruited. The comparison group used standard methods of HIV prevention, testing, and treatment services. No additional services were provided to the comparison group. The intervention began after the completion of the baseline assessment and lasted until the termination of the study at 24 months. The intervention was designed to work at the community level. Detailed study methodology is available in previous manuscripts [28].

Data Collection

Data collection occurred at baseline and at 12- and 24- month follow-up. At each assessment, trained study personnel read the questionnaire to participants and entered their responses into a computer using the computer administered personal interview (CAPI) method. Questionnaire items included demographic variables, sexual risk behaviors, and perceptions of stigma.

Measures

Measures included demographic variables, history of HIV testing, and five stigma items (1–5 rating, 1 = strongly agree with statement, indicating high stigma; 5 = strongly disagree, indicating low stigma). The stigma items were designed to broadly measure stigma. One of the items was reverse coded on the questionnaire and recoded for the present analysis. One item in the stigma scale was tailored for the Peru site [28] (see Table 1 for list of items).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants at baseline in urban, coastal Peru

| Comparison (N = 1,722) | Intervention (N = 1,327) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD) | 24.3 (5.5) | 24.1 (5.6) | 0.35 |

| Years of education (mean, SD) | 9.4 (2.3) | 9.2 (2.4) | 0.03 |

| Gender | 0.01 | ||

| Male | 91.5% | 88.6% | |

| Female | 8.5% | 11.4% | |

| Regional background | 0.54 | ||

| Coast (not Lima) | 57.4% | 57.6% | |

| Highlands | 5.4% | 6.3% | |

| Jungle | 1.6% | 2.2% | |

| Metropolitan Lima | 25.6% | 24.7% | |

| Lima (other) | 10.0% | 9.2% | |

| Marital status | 0.18 | ||

| Married/live with partner | 24.0% | 25.6% | |

| Never married/single | 71.6% | 68.7% | |

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 4.4% | 5.7% | |

| Tested for HIV previously | 0.93 | ||

| Yes | 28.0% | 27.8% | |

| No | 72.0% | 72.2% | |

| Returned for results | 0.26 | ||

| Yes | 86.5% | 83.7% | |

| No | 13.5% | 16.3% | |

| Regularly earn money | <0.01 | ||

| Yes | 85.5% | 78.5% | |

| No | 14.5% | 21.6% | |

| Self-rated health | 0.16 | ||

| Excellent | 5.3% | 7.1% | |

| Good | 28.3% | 27.9% | |

| Fair | 62.3% | 63.3% | |

| Poor | 4.2% | 1.7% | |

| Risk group | 0.02 | ||

| Esquineros | 74.5% | 73.6% | |

| Homosexuales | 17.0% | 15.0% | |

| Movidas | 8.5% | 11.4% | |

| # of episodes of genital discharge in previous 6 months (mean, SD) | 0.32 (3.7) | 0.40 (2.4) | 0.49 |

| Stigma items | |||

| “An HIV positive person must have done something inappropriate and deserves to be punished” | <0.01 | ||

| Strongly disagree/disagree | 72.4% | 67.3% | |

| Strongly agree/agree/indifferent, not sure | 27.6% | 32.7% | |

| “I believe that people with HIV should be isolated” | <0.01 | ||

| Strongly disagree/disagree | 72.0% | 67.0% | |

| Strongly agree/agree/indifferent, not sure | 28.0% | 33.0% | |

| “There is security in someone with HIV taking care of the children of others” | <0.01 | ||

| Strongly disagree/disagree | 24.4% | 30.3% | |

| Strongly agree/agree/indifferent, not sure | 75.6% | 69.7% | |

| “I do not want to be friends with someone who has AIDS” | 0.47 | ||

| Strongly disagree/disagree | 78.9% | 79.0% | |

| Strongly agree/agree/indifferent, not sure | 22.1% | 21.0% | |

| “Everyone in this country should get an HIV test and everyone who is positive should have a tattoo in order to be recognized” | <0.01 | ||

| Strongly disagree/disagree | 69.90% | 63.1% | |

| Strongly agree/agree/indifferent, not sure | 30.1% | 36.9% | |

All scientific and research procedures were overseen by the UCLA Human Subjects Protection Committee, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia ethics committee and the RTI Institutional Review Board. Participants signed an informed consent prior at the baseline assessment.

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square tests were used to test independence of group assignment on demographic variables and stigma items. We used two-sample t-tests to compare mean differences in age and years of education.

The five stigma items were recoded into dichotomous variables (items where participants strongly agreed, somewhat agreed, or were indifferent/unsure were coded as high stigma; items where participants strongly disagreed or disagreed were coded as low stigma). The stigma items were entered into a stigma index (alpha = 0.55) based on the sum of the recoded five items (higher score indicates greater stigma). In each of the five items, 0 = no stigma, 1 = stigma. The index therefore ranged from 0 to 5 (0 = no/low stigma, 5 = high stigma). The stigma index value was a conservative measure because for each item that indicated stigma (originally ranked 1–5), the item was coded as “stigma” if the response was strongly agree/agree/not sure, or “no stigma” if the response was strongly disagree/disagree. We conducted sensitivity analysis and ran the analysis using the dichotomized scale as well as the sum of the 5-point scale. We found that the results were consistent and robust and therefore decided to keep the dichotomized scale to aid in interpretability.

Mixed effects modeling was used to assess the impact of the intervention on stigma from baseline to 24-month follow-up, controlling for age, education, gender, and income. Additional items from the questionnaire were entered as covariates into the models if we found significant baseline differences between groups or if they were theoretically or empirically identified as potential confounders. These mixed effects models were also conducted within the three subgroups, esquineros, homosexuales, and movidas. Analyses were conducted using Stata software version 10.1 (Stata Corporation College Station, TX).

Results

Study Sample

The 252 CPOLs from the intervention group were excluded from the analysis. The baseline sample included 3049 (comparison, n = 1,722; intervention, n = 1,327) participants. Of the 3,049 participants, 3,023 (99%) completed the stigma items. Table 1 shows significant baseline differences between the comparison and treatment groups on demographic and stigma items. Differences were found based on gender (greater percentage of men within the comparison group), income (greater percentage of participants in the comparison group regularly earn money), risk group (i.e., esquineros, homosexuales, and movidas), education (those in the comparison group had slightly more years of education), and four of the five stigma items. For all stigma items, the majority of participants in both comparison and treatment groups did not endorse stigmatizing views about people with HIV.

Attrition

The 252 CPOLs from the intervention group were not included in this analysis and therefore the number of participants in the comparison group is greater than the number of participants in the intervention group. Of the 3,049 total participants, 2,655 (87.1%) (intervention, n = 1,110, comparison, n = 1,545) completed the 12-month assessment and 2,448 (80.3%) (intervention, n = 1,033, comparison, n = 1,415) completed the 24-month assessment.

Intervention Effects

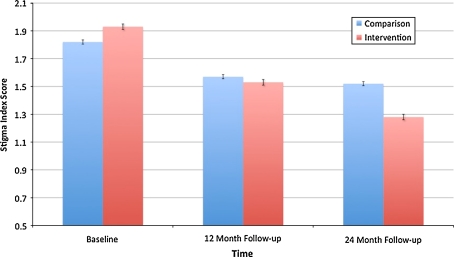

Table 2 shows the results of the intervention on stigma. Participants in the intervention showed a significant reduction in stigma from baseline to 12-month follow-up and baseline to 24-month follow-up. Main effects were found for time such that all participants showed significant reductions in stigma from baseline to 12-month follow-up and baseline to 24-month follow-up (see Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Analysis of stigma index ratings in urban, coastal Peru

| Coefficient | CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.02 | (−0.02, −0.01) | <0.01 |

| Years of education | −0.10 | (−0.12, −0.09) | <0.01 |

| Gender (male) | −0.09 | (−0.12, −0.09) | 0.12 |

| Regularly earn money | 0.02 | (−0.07, 0.12) | 0.64 |

| Time | |||

| Baseline | – | – | – |

| Baseline–12 month | −0.26 | (−0.32, −0.19) | <0.01 |

| Baseline–24 month | −0.31 | (−0.37, −0.24) | <0.01 |

| Intervention group | 0.08 | (−0.00, 0.17) | 0.06 |

| Time × intervention group | |||

| Baseline × intervention group | – | – | – |

| Baseline–12 month × intervention group | −0.13 | (−0.22, −0.03) | 0.01 |

| Baseline–24 month × intervention group | −0.33 | (−0.43, −0.23) | <0.01 |

CI Confidence interval

Fig. 1.

Stigma, 2003–2005 urban, coastal Peru

We also found differences between comparison and intervention groups within the three sub-groups. For esquineros, we found a significant decrease in stigma from baseline to 12-month and baseline to 24-month follow-up. A main effect for time was found such that reports of stigma decreased from baseline to 12-month and baseline to 24-month follow-up (Table 3). For homosexuales, we found a significant decrease in stigma from baseline to 24-month follow-up. No significant main effects were found for time (Table 4). For movidas, we found no significant differences in stigma between groups from baseline to either 12- or 24-month follow-up (Table 5). Main effects for time were found for time such that stigmatization decreased from baseline to 12- and baseline to 24-month follow-up.

Table 3.

Analysis of stigma index ratings among esquineros in urban, coastal Peru (N = 2,259)

| Coefficient | CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.01 | (−0.02, −0.00) | <0.01 |

| Years of education | −0.10 | (−0.11, −0.08) | <0.01 |

| Regularly earn money | 0.07 | (−0.05, 0.18) | 0.27 |

| Time | |||

| Baseline | – | – | – |

| Baseline–12 month | −0.25 | (−0.33, −0.18) | <0.01 |

| Baseline–24 month | −0.31 | (−0.39, −0.24) | <0.01 |

| Intervention group | 0.05 | (0.05, 0.15) | 0.37 |

| Time × intervention group | |||

| Baseline × intervention group | – | – | – |

| Baseline–12 month × intervention group | −0.15 | (−0.27, −0.03) | 0.01 |

| Baseline–24 month × intervention group | −0.31 | (−0.43, −0.19) | <0.01 |

CI Confidence interval

Table 4.

Analysis of stigma index ratings among homosexuales in urban, coastal Peru (N = 491)

| Coefficient | CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.01 | (−0.02, 0.01) | 0.43 |

| Years of education | −0.05 | (−0.08, −0.02) | <0.01 |

| Regularly earn money | 0.06 | (−0.14, 0.26) | 0.55 |

| Time | |||

| Baseline | – | – | – |

| Baseline–12 month | −0.13 | (0.26, 0.01) | 0.06 |

| Baseline–24 month | 0.13 | (−0.27, 0.01) | 0.07 |

| Intervention group | 0.15 | (−0.03, 0.33) | 0.11 |

| Time × intervention group | |||

| Baseline × intervention group | – | – | – |

| Baseline–12 month × intervention group | −0.03 | (−0.24, 0.18) | 0.79 |

| Baseline–24 month × intervention group | −0.41 | (−0.63, −0.19) | <0.01 |

Table 5.

Analysis of stigma index ratings among movidas in urban, coastal Peru (N = 297)

| Coefficient | CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.00 | (−0.1, 0.02) | 0.64 |

| Years of education | −0.11 | (−0.15, 0.07) | <0.01 |

| Regularly earn money | 0.04 | (−0.16, 0.24) | 0.67 |

| Time | |||

| Baseline | – | – | – |

| Baseline–12 month | −0.53 | (−0.74, −0.33) | <0.01 |

| Baseline–24 month | −0.58 | (−0.79, −0.37) | <0.01 |

| Intervention group | 0.11 | (−0.14, 0.37) | 0.39 |

| Time × intervention group | |||

| Baseline × intervention group | – | – | – |

| Baseline–12 month × intervention group | −0.02 | (−0.31, 0.27) | 0.88 |

| Baseline–24 month × intervention group | −0.2 | (−0.49, 0.10) | 0.19 |

Discussion

Results suggest that a community popular opinion intervention can reduce HIV-related stigma among esquineros, homoesexuales, and movidas living in three cities in urban, coastal Peru. Compared to people who lived in comparison communities, those who lived in communities with popular opinion leaders reported less HIV-related stigma over a 12- and 24-month period.

HIV-related stigma has been divided into various types of stigma, including enacted stigma/discrimination, fear of HIV transmission, negative judgments and beliefs about HIV, layered stigma (stigma toward marginalized groups), and potential stigma [12, 30]. People can become susceptible to stigmatization through a variety of situations, including going to get tested for HIV, receiving a positive diagnosis, receiving post-test counseling, or going on treatment [8, 31, 32]. For example, merely choosing to test for HIV signals to others that the tester may have contracted HIV or have participated in (stigmatized) behavior that could lead to HIV infection. The potential stigmatization associated with testing can lead people being tested to be perceived as generally immoral individuals who are more likely to lie, shoplift, cheat, and steal [12]. Actually receiving a positive diagnosis can result in further stigmatization, including the loss of family ties, friendship, employment and housing, dismissal from school, and denial of health/life insurance and health care [8–11, 13].

Approaches to reduce stigma should focus on addressing one or more of these situations that can lead to stigmatization. One common method for reducing stigma focuses on normalizing stigmatizing behaviors [33–35]. Increasing HIV testing rates, HIV prevention behaviors, and conversations about HIV risk behaviors, can increase awareness that these behaviors are socially common and acceptable. For example, opt-out HIV testing may be able to decrease stigma by making HIV testing a normative behavior [34, 36].

The current results are based on an intervention designed to normalize HIV prevention behaviors by having peer leaders deliver conversations and messages about HIV. While qualitative studies are being conducted to better understand how the intervention reduced stigma, it is possible that (1) the increase in conversations about HIV (in the intervention group) and (2) the requirement for HIV testing (within both the intervention and comparison communities) produced a shift in social norms that reduced HIV stigma. As intended by the intervention, there were a greater number of conversations about HIV within the intervention communities compared to comparison communities. HIV-related stigma may therefore have been reduced in the intervention communities as participants increased their conversations about HIV, and saw popular peers in their communities talking openly about HIV. HIV testing was conducted within both the intervention and comparison communities. This increased prevalence of testing within the intervention and comparison communities may have further reduced HIV-related stigma in the intervention communities, and might explain the main effect for reduced stigma over time as even the comparison community saw a slight reduction in stigma over time due to the increased testing within the communities (see Fig. 1).

This analysis has several limitations. Results from this Peruvian sample may be difficult to generalize to other populations. Stigma differs by culture and region and the present results from a popular opinion leader intervention may differ in other populations. However, we feel that these results can generalize to other similar populations from socially marginalized groups in Latin America because we sampled a diverse population (including women and men with multiple HIV risk behaviors, from three urban areas of Peru). While this analysis is one of the first to study HIV-related stigma in Peru (and in South America, in general), future research may explore how stigma differs within South American countries. Next, the stigma analysis presented is based on an index of five stigma items, and this may have contributed to the borderline reliability coefficient. While we feel that these five items are a good representation of perceptions of stigma, a greater number of stigma-related items would increase response reliability. While the current reliability (alpha = 0.55) is below the recommended value of 0.6 or 0.7, coefficients above 0.5 have been labeled as suitable and used in previous studies [37]. Future studies will be able to include additional stigma items and increase reliability. Finally, the intervention was designed to increase HIV-related communication in order to increase prevention behaviors. Although this study analyzes the effects of the intervention on stigma, stigma reduction was not a primary goal of the intervention and we do not know the exact mechanism by which the intervention reduced stigma. Although the study aims were not designed to directly reduce stigma, each of them may potentially affect social norms and perceptions of HIV-related stigma through increasing conversations about HIV and HIV testing. We believe that both increasing the number of HIV-related conversations as well as the communicating tailored HIV prevention messages helped to reduce stigma in the intervention communities. Future research can better determine the precise mechanism that led the intervention to reduce stigma.

Conclusion

Within a population of esquineros, homosexuales, and movidas, from three cities in Peru, an intervention designed using community popular opinion leaders to disseminate HIV prevention messages was able to reduce stigma compared to the comparison group. Findings suggest that interventions designed to normalize HIV prevention behaviors using conversations about HIV can decrease HIV-related stigma.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Institute of Mental Health.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Doherty T, Chopra M, Nkonki L, Jackson D, Greiner T. Effect of the HIV epidemic on infant feeding in South Africa: “when they see me coming with the tins they laugh at me”. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84(2):90–96. doi: 10.2471/BLT.04.019448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalichman S, Simbayi L. HIV testing attitudes, AIDS stigma, and voluntary HIV counselling and testing in a black township in Cape Town, South Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79(6):442–447. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.6.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell C, Nair Y, Maimane S, Sibiya Z. Understanding and Challenging HIV/AIDS Stigma. In: CfHAN, editor. HIVAN. Durban: University of Kwa-Zulu Natal; 2005.

- 4.Nyblade L, Field M. Community involvement in prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) initiatives. Women, communities and the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: issues and findings from community research in Botswana and Zambia. Washington: International Center for Research on Women; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bond V, Chase E, Aggleton P. Stigma, HIV/AIDS and prevention and mother-to-child transmission in Zambia. Eval Program Plann. 2002;25(4):347–356. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7189(02)00046-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carr RL, Gramling LF. Stigma: a health barrier for women with HIV/AIDS. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2004;15(5):30–39. doi: 10.1177/1055329003261981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Stigma and discrimination. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2006.

- 8.Chesney MA, Smith AW. Critical delays in HIV testing and care—the potential role of stigma. Am Behav Sci. 1999;42(7):1162–1174. doi: 10.1177/00027649921954822. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Folkman S, Chesney MA, Cooke M, Boccellari A, Collette L. Caregiver burden in HIV-positive and HIV-negative partners of men with AIDS. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62(4):746–756. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.62.4.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JD, Craft EA. Protecting one’s self from a stigmatized disease…once one has it. Deviant Behav. 2002;23:267–299. doi: 10.1080/016396202753561248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herek G. Illness, stigma, and AIDS. In: Costa PT Jr, VandenBos GR, editors. Psychological aspects of serious illness: chronic conditions, fatal diseases, and clinical care. Washington: APA; 1990. pp. 103–150. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young SD, Nussbaum AD, Monin B. Potential moral stigma and reactions to testing for sexually transmitted diseases: evidence for a disjunction fallacy. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2007;33(6):789–799. doi: 10.1177/0146167207301027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tross S, Hirsch DA. Psychological distress and neuropsychological complications of HIV infection and AIDS. Am Psychol Special Issue: Psychol AIDS. 1988;43(11):929–934. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.43.11.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herek GM, Capitanio JP, Widaman KF. HIV-related stigma and knowledge in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1991–1999. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(3):371–377. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.3.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lentine D, Hersey J, Iannacchione V, Laird G, McClamroch K, Thalji L. HIV-related knowledge and stigma—United States. MMWR. 2000;49(47):1062–1064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nyblade LC. Measuring HIV stigma: existing knowledge and gaps. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11(3):335–345. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown L, Macintyre K, Trujillo L. Interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: what have we learned? AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15(1):49–69. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.49.23844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiss MG, Ramakrishna J, Somma D. Health-related stigma: rethinking concepts and interventions. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11(3):277–287. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogden J, Nyblade L. Common at its core: HIV and AIDS-related stigma across contexts. Washington: International Center for Research on Women; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Konda K, Caceres CF, Coates TJ. Epidemiology, prevention and care of HIV in Peru. In: Celentano DD, Beyrer C, editors. Public health aspects of HIV/AIDS in low and middle income countries. New York: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clark JL, Konda KA, Segura ER, et al. Risk factors for the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men infected with HIV in Lima, Peru. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84(6):449–454. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.031310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clark JL, Long CM, Giron JM, et al. Partner notification for sexually transmitted diseases in Peru: knowledge, attitudes, and practices in a high-risk community. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(5):309–313. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000240289.84094.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caceres CF, Rosasco AM. The margin has many sides: diversity among gay and homosexually active men in Lima. Cult Health Sex. 1999;1(3):261–275. doi: 10.1080/136910599301012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caceres CF, Marin BV, Hudes ES, Reingold AL, Rosasco AM. Young people and the structure of sexual risks in Lima. AIDS. 1997;11(Supp 1):S67–S77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurst FP, Neff RT, Falta EM, et al. Incidence, predictors, and associated outcomes of prostatism after kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(2):329–336. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04370808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salazar X, Caceres C, Rosasco A, et al. Vulnerability and sexual risk: vagos and vaguitas in a low-income town in Peru. Cult Health Sex. 2005;7:375–387. doi: 10.1080/13691050500100849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark J, Long C, Giron M, et al. Partner notification and sexually transmitted infections in Peru: knowledge, attitudes, and practices in a high-risk community. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:309–313. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000240289.84094.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maiorana A, Kegeles S, Fernandez P, et al. Implementation and evaluation of an HIV/STD intervention in Peru. Eval Program Plann. 2007;30(1):82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogers E. Diffusion of innovations. 4. New York: Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nyblade L, MacQuarrie K. Can we measure HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination? Current knowledge about quantifying stigma in developing countries In: ICfRoW, editor. ICRW. Washington: USAID; 2006. http://www.policyproject.com/pubs/generalreport/Measure%20HIV%20Stigma.pdf.

- 31.Fortenberry JD, McFarlane M, Bleakley A, Bull S. Relationships of stigma and shame to gonorrhea and HIV screening. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(3):378–381. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.3.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myers T, Orr K, Locker D, Jackson E. Factors affecting gay and bisexual men’s decisions and intentions to seek HIV testing. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:701–704. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.83.5.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Basset M. Ensuring a public health impact of programs to reduce HIV transmission from mothers to infants: the place of voluntary counseling and testing. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(3):347–351. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Branson B, Handsfield H, Lampe M, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR. 2006;55(14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu Z, Sun X, Sullivan SG, Detels R. Public health: HIV testing in China. Science. 2006;312(5779):1475–1476. doi: 10.1126/science.1120682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Young SD, Monin B, Owens D. Opt-out testing for stigmatized diseases: a social psychological approach for understanding the potential effect of recommendations for routine HIV testing. Health Psychol. 2009;28(6):675–681. doi: 10.1037/a0016395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi C. Modern statistical analysis. Seoul: Bokdoo Co; 2000. [Google Scholar]