Abstract

Anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (ED1) is characterized by hypotrichosis, reduced number of sweat glands, and incisior anodontia in human, mouse, and cattle. In affected humans and mice, mutations in the ED1 gene coding for ectodysplasin 1 are found. Ectodysplasin 1 is a novel trimeric transmembrane protein with an extracellular TNF-like signaling domain that is believed to be involved in the formation of hair follicles and tooth buds during fetal development. We report the construction of a 480-kb BAC contig harboring the complete bovine ED1 gene on BTA Xq22–Xq24. Physical mapping and sequence analysis of the coding parts of the ED1 gene revealed that a large genomic region including exon 3 of the ED1 gene is deleted in cattle with anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia in a family of German Holstein cattle with three affected maternal half sibs.

[The sequence data described in this paper have been submitted to the EMBL nucleotide database under accession nos. AJ300468, AJ300469, and AJ278907.]

Many inherited disorders of domestic animals, which are analogous to human hereditary diseases, have been reported, and these are believed to be valuable for research on the human diseases (Patterson et al. 1988). More than 300 known inherited diseases in cattle (Nicholas 1998) are similar to human diseases, for example, leukocyte adhesion deficiency (Shuster et al. 1992) and deficiency of uridine monophosphate synthase (Schwenger et al. 1993). The investigation of affected cattle as potential animal models of human genetic disorders will provide useful information regarding pathogenesis of rare human diseases with identical molecular basis.

Cattle with X-linked anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (ED1 also called EDA or XLHED) are characterized by hypotrichosis, a reduced number of sweat glands, and tooth abnormalities such as missing incisors and missing or defective molars (Wijeratne et al. 1988; Drögemüller et al. 2000a; MIA000543). Anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia is also known in human (MIM305100) and mouse. Mutations in the ED1 gene have been shown to be responsible for human X-linked anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia 1 (Kere et al. 1996; Monreal et al. 1998) as well as for the phenotype of the Tabby mouse mutant (Srivastava et al. 1997).

The giant ∼300-kb ectodysplasin 1 gene ED1 has not yet been characterized completely. To identify the human ED1 gene, Srivastava et al. (1996) fine mapped the translocation breakpoint in a X-linked ED1 patient with a t(X;1)(q13.1;p36.3) translocation and Kere et al. (1996) described the positional cloning of the gene, consisting of two exons, which is expressed in keratinocytes, hair follicles, sweat glands, and in other adult and fetal tissues. Analysis of ED1 patients with no apparent mutations in the two ED1 exons described by Kere et al. (1996) led to the discovery of seven new exons at the 3′-end of the ED1 gene (Monreal et al. 1998). A total of eight different alternative splice forms were reported (Bayés et al. 1998). The longest transcript was termed ED1-A1 and codes for a 391-amino acid transmembrane protein, ectodysplasin 1. Another transcript called ED1-A2 differs from ED1-A1 by the absence of six nucleotides encoded by exon 8. The ectodysplasin 1 isoforms ED1-A1 and ED1-A2 represent transmembrane proteins with an intracellular N terminus. The extracellular part of these two isoforms contains a collagen-like Gly-X-Y repeat that mediates trimerization and a TNF-like signaling domain at the C terminus. These findings suggested that ectodysplasin 1 is involved in the early epithelial-mesenchymal interaction that regulates ectodermal appendage formation (Ezer et al. 1999). The two isoforms differ by the presence or absence of the two amino acids 308E and 309V located in the TNF domain. Interestingly, ED1-A1 and ED1-A2 bind to two different receptors, that is, ED1-A1 binds to downless (DL), also called ED1R, whereas ED1-A2 binds to a receptor termed XEDAR (Yan et al. 2000). The transcripts for ED1-A1 and EDA-A2 consist of exons 1 and 3–9 of the ED1 gene. Six other transcripts that have been detected utilize different portions of exons 1 and 2 and code for truncated proteins, which lack the collagenous domain and the TNF domain. However, the biological significance of the shorter isoforms remains unclear.

Ectodysplasin 1 is highly homologous to the protein mutated in the Tabby mouse. Ferguson et al. (1997) identified a candidate cDNA for the the murine equivalent of ED1 by phenotype analysis and syntenic mapping. Srivastava et al. (1997) cloned the mouse tabby gene (ta) and found it to be homologous to the ED1 gene. They showed that the gene is expressed in developing teeth and epidermis and found no expression in corresponding tissues from Tabby mice.

We investigated a family of German Holstein cattle with X-chromosomal recessive inheritance of the disease (O. Distl, pers. comm.). IBD mapping with X-chromosomal microsatellite markers narrowed the candidate region to the interval between BMS417 and BMS2798 on the proximal part of Xq (Sonstegard et al. 1997; O. Distl, pers. comm.). Candidate genes within this region were derived by comparative mapping from syntenic regions on the human and murine X-chromosomes, respectively (Band et al. 2000). The strongest candidate that could be found was the ED1 gene coding for ectodysplasin 1. Therefore, we isolated bovine BAC clones containing all eight exons of the ∼300-kb ED1 gene that contribute to the longest splice forms ED1-A1 and ED1-A2. One of the BAC clones was used to establish the chromosomal location of the bovine ED1 gene within the candidate region on BTA Xq22–Xq24 by physical mapping (Kuiper et al. 2001). Analysis of one of the BAC clones revealed a CA dinucleotide repeat sequence located in intron 4 of the ED1 gene and linkage mapping of this novel ED1 microsatellite confirmed the gene localization in the identified genetic interval (Drögemüller et al. 2000b). To elucidate the genomic structure of the ED1 gene, we cloned the bovine ED1 gene and sequenced the coding parts with flanking regions. In addition to the genomic sequence of the ED1 gene, we present evidence that bovine anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia is caused by deletion of exon 3 of the bovine ED1 gene.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

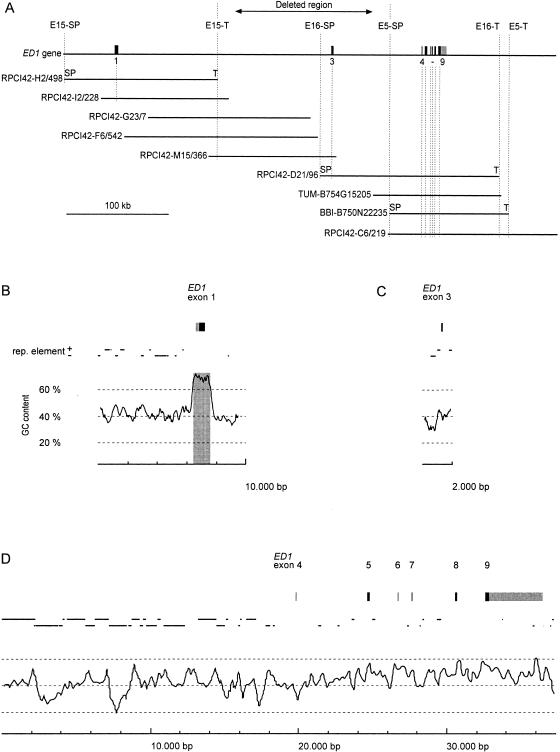

Cloning of the Bovine ED1 Gene

To isolate the bovine ED1 gene, we screened genomic BAC libraries (Zhu et al. 1999; Warren et al. 2000) with radioactively labeled probes. The probes consisted of a human cDNA clone containing exon 1 of the ED1 gene and two bovine PCR products containing parts of exons 3 and 9 of the ED1 gene. Heterologous primers for these PCR products were designed from the human ED1 sequence (GenBank accession no. AF040628). This led to the isolation of nine overlapping BAC clones spanning ∼480 kb of the bovine genomic DNA sequence. The contig contained the complete bovine ED1 gene. Partial sequence analysis of this 480-kb contig revealed the presence of eight ED1 exons with the entire ORF of the ED1-A1 and ED1-A2 isoforms. A 9596-bp fragment from the BAC RPCI42-H2/498 containing the first exon, a 2015-bp fragment from BAC RPCI42-D21/96 containing exon no. 3, and a 37331-bp fragment from BAC BBI-B750N22235 containing exons 4–9 were sequenced and submitted to the EMBL database (accession nos. AJ300468, AJ300469, AJ278907). The numbering of the exons was performed in accordance with the nomenclature of Bayes et al. (1998). The positions of the isolated clones and ED1 exons are illustrated in Figure 1. A 1500-bp-spanning CpG island was detected at the 5′-end of the ED1 gene. The overall GC content of the reported sequence is 43.9%. Repetitive sequences make up 41.4% of the 48942 bp that were determined. The distribution of the GC content and repetitive elements along the sequence is illustrated in Figure 1B–D.

Figure 1.

(A) Genomic structure of the bovine ED1 gene. Exons are numbered according to the nomenclature of Bayés et al. (1998). The positions of the isolated BAC clones are represented by horizontal bars in the lower part. The deleted genomic region in ED1-affected cattle is marked by an arrow. Vertical broken lines indicate STS loci used for physical mapping of the BAC contig. (B,C,D) Exons of the ED1 gene are shown as boxes. Untranslated regions are shown in gray, whereas protein-coding parts are shown in black. The positions and orientations of repetitive elements (SINE, LINE, LTR) are indicated by solid lines. In the lower part of the figure, the GC content is shown. A 300-bp window size was used for the calculation of the GC content. The shaded box highlights a CpG island in the region of the promotor and exon 1 of the bovine ED1 gene.

Analysis of the Genomic Structure of the Bovine ED1 Gene

Exon/intron boundaries of the bovine ED1 gene were determined by comparison of the bovine genomic DNA sequence with the human ED1 cDNA sequence. In addition, a bovine cDNA fragment containing all junctions between the exons was generated by RT–PCR, sequenced, and used for comparison with the genomic sequence. From these analyses it became clear that the bovine ED1 gene consists of eight exons separated by seven introns. These exons correspond to the human exons 1 and 3–9. The bovine ED1 gene spans ∼320 kb, of which >200 kb are contained in the first intron and >75 kb in the second intron. According to a draft sequence of the Human Genome Project, the size of the human ED1 intron 1 is ∼340 kb (Genbank accession no. NI011838). All splice donor/splice acceptor sites conform to the GT/AG rule. The exon/intron junctions in the protein coding region of the ED1 gene are well conserved between human and cattle. The DNA sequences at the exon/intron boundaries are summarized in Table 1. To test whether sequences homologous to the human ED1 exon 2 are present in the bovine ED1 gene, we hybridized DNA from the nine BAC clones with a human exon 2 PCR product as probe, but no hybridization signal was observed. PCR with heterologous primers derived from human exon 2 sequences on the bovine BAC clones or on bovine genomic DNA also did not result in a specific amplification. With the exception of the missing exon 2, the observed genomic organization of the ED1 gene in cattle was very similar to the human ED1 gene (Bayés et al. 1998) and the mouse ta gene (Srivastava et al. 1997).

Table 1.

Exon-Intron Junctions of the Bovine ED1 Gene

| Exon size | 5′ Intron/Exon…Exon/Intron 3′ | Intron size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | (bp) | No. | (bp) | Phase | |

| 1 | 685 | AGCACC…CACCAGgtgagtcact | 1 | >200 kb | 0 |

| 3 | 106 | tatttttcagATGGCC…CAGATGgtaagtctgc | 3 | >75 kb | 1 |

| 4 | 24 | tttttaatagGTCCTG…AAAAGGgtaagtcaat | 4 | 4786 | 1 |

| 5 | 180 | catctttcagGAAAGA…CTTCTGgtgagttcct | 5 | 1890 | 1 |

| 6 | 35 | tattttgcagGTGCTG…AACCAGgttggctggg | 6 | 895 | 0 |

| 7 | 52 | atcctcccagCCAGCC…AGAATGgtaagagtca | 7 | 2864 | 1 |

| 8 | 131 | tcatactgagATCTTT…AGTCAGGTAGAAgtgagtacgg | 8 | 1891 | 0 |

| Exon 8 a (125 bp) Exon 8 b (6 bp) | |||||

| 9 | >3861 | tctcccccagGTATAC…GCAAATAAAGCTTTTTC | |||

Exon sequences are shown in uppercase letters, and intron sequences in lowercase letters. Untranslated regions are shown in italics. The conserved GT/AG exon/intron-junctions are shown in bold type.

For the first exon, the putative transcription start site is shown instead of a splice acceptor; for the last exon, the polyadenylation signal is shown in bold italics instead of exon/intron junction. For exon 8, the internal alternative splice donor site is shown and the nucleotides corresponding to exon 8b are underlined.

The transcription start site of the bovine ED1 gene was tentatively assigned by sequence alignment with the human ED1 sequence (Pengue et al. 1999). The region immediately surrounding the transcription start site is highly conserved between human and cattle. The promoter of the bovine ED1 gene is GC rich with a GC content of 67.0% in the 300 nucleotides preceding the transcription start site (see also Fig. 1B). Like other GC-rich promoters, it does not contain a TATA box or a CAAT box.

Analysis of the Bovine ED1 cDNA Sequence

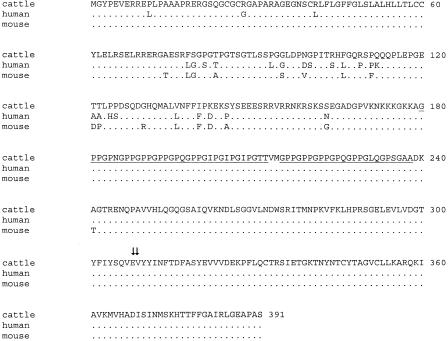

The bovine ED1 cDNA sequence is ∼5 kb long with an ORF including the stop codon of 1176 nucleotides (isoform ED1-A1) or 1170 nucleotides (isoform ED1-A2), respectively, and a 5′-UTR of 289 nucleotides. The 1176-bp ORF of ED1-A1 is 92% identical to the coding region of the human ED1-A1 and 91.2% to the murine Ta-A transcript. At the 3′-end, two canonical polyadenylation signals AATAAA are found within 755 bp. Depending on which polyadenylation signal is used, this would result in 3′-UTRs of 2.8 and 3.6 kb, respectively. The 3′-ends of human and mouse ED1 cDNA sequences also show two polyadenylation signals at homologous positions, and in these species, the second signal seems to be used preferentially (Srivastava et al. 1997; Bayés et al. 1998). The bovine ED1-A1 mRNA is predicted to encode a 391 amino acid protein that is 94.4% identical to the human and 95.4% identical to the mouse protein. Most amino acid exchanges are located at the N terminus, whereas the collagen-like domain and the TNF-like domain are extremely well conserved (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Alignment of the ectodysplasin 1 (ED1-A1) amino acid sequences of cattle, human, and mouse. The interrupted (Gly-X-Y)19 repeat is underlined. Arrows mark the amino acids 308E and 309V that are absent from the ED1-A2 isoform. Note the extremely high-sequence conservation of the proteins in the C-terminal region that harbors the TNF-like signaling domain.

RT–PCR from bovine skin and kidney mRNA by use of sense and antisense primers from exon 1 and 9 amplified transcripts corresponding to ED1-A1 and ED1-A2, which was verified by direct DNA sequencing of the RT–PCR products. Similar to the human ED1 sequence, the use of an additional internal splice donor in exon 8 produces ED1-A2, which lacks the 6-nucleotide designated exon 8b (Bayes et al. 1998). Sequencing of RT–PCR products with a forward primer from the end of exon 1 paired with different reverse primers from exons 3, 5, and 7 revealed no evidence for the existence of additional alternative splice forms. The isoforms ED1-A1 and ED1-A2 seem to represent the only physiological ED1 transcripts in the investigated tissues, as no other RT–PCR bands were detected after performing 35 PCR cycles. No bovine ED1 transcript corresponding to the original human 854-bp ED1 transcript encoding the isoform ED1-O (Kere et al. 1996) could be detected. This was confirmed by 3′-RACE experiments using nested forward primers in exon 1 paired with a (T)24V primer, in which no bands could be generated. This is another indication that exon 2, which is used in the human ED1-O transcript, is not conserved between human and cattle. Because of the very large size of intron 1, it might be possible that aberrant splicing at cryptic splice sites within the intron 1 sequence occurs and that the shorter splice forms detected by sensitive RT–PCR methods in other species correspond to such aberrant splicing events. Our results underline the significance of the ED1-A1 and ED1-A2 transcripts, which are expressed in both investigated tissues, that is, skin and kidney from adult cattle. The ED1 expression in kidney that was also reported in other species (Kere et al. 1996; Srivastava et al. 1997) suggests that the ectodysplasin 1 protein may serve additional functions other than the previously described signaling role in the development of ectodermal appendages.

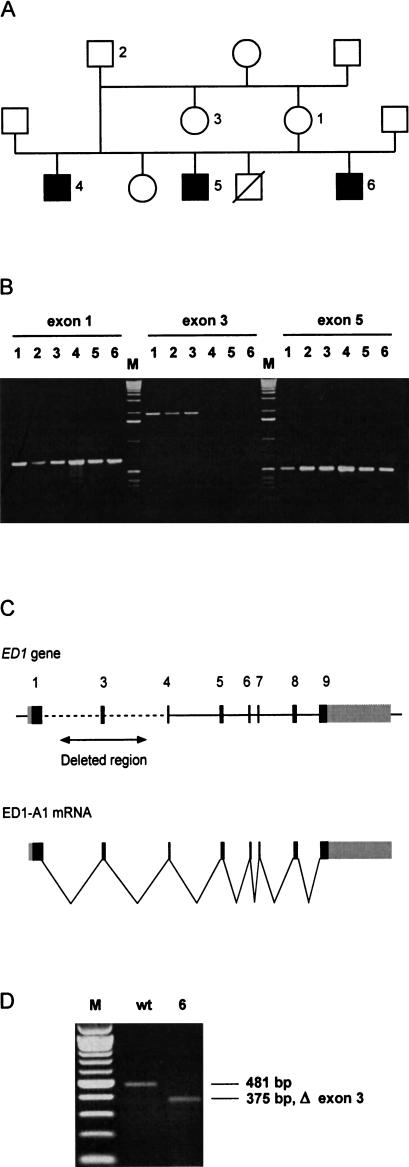

Mutation Analysis

On the basis of exon/intron boundaries, primers were designed to amplify and sequence each individual ED1 exon from six probands (Fig. 3). DNA samples from three affected calves and three healthy family members were amplified by PCR and screened for mutations by sequencing. Our experiments revealed that exon 3 could not be amplified from affected animals, indicating a deletion of this exon. Three different primer pairs flanking exon 3 were used to rule out any polymorphisms that affect only the primer binding sites. The deletion in the affected animals spanned a large genomic region of at least 2 kb, but might be up to 160 kb in size (Fig. 1A). All other ED1 exons were normal and did not show any alterations between affected and unaffected animals. PCR on 77 male unrelated control animals from three different breeds showed that this deletion is not present in healthy cattle. RT–PCR confirmed that the ED1 mRNA from affected animals lacked the 106-nucleotide exon 3 (Fig. 3D). The deletion produces a frameshift, leading to a truncated protein that lacks the collagen-like trimerization domain as well as the TNF-like signaling domain of the ectodysplasin A1 and A2 proteins. Therefore, it is highly plausible that the phenotype in the cattle with ectodermal dysplasia is caused by the deletion of exon 3 of the ED1 gene. In human and mouse, many different mutations within the ED1 gene are known that lead to comparable phenotypes. Although most human patients have point mutations within the ED1 gene, one report described a human patient who also had a deletion of exon 3 similar to the genetic lesion observed in the ED1 cattle of this study (Bayés et al. 1998). In these cases, apparently a similar mutation occurred independently in cattle and humans.

Figure 3.

(A) ED1 cattle family used in this study. In this pedigree, a subset of the animals from a previous study is shown (Drögemüller et al. 2000a). (B) Identification of deletions within the ED1 gene in affected animals. ED1 exons were PCR amplified from animals 1–6 (Fig. 3A). PCR primers flanking exon 3 did not generate PCR products on the DNA of affected animals 4–6, indicating a deletion of this genomic region. (M) 1-kb ladder; (exon 1) 661-bp product, (exon 3) 2006-bp product, (exon 5) 535-bp product with M13-tagged PCR primers). (C) Genomic organization of the mammalian ED1 gene. ED1-A1 and ED1-A2 differ by the presence or absence of 6 nucleotides encoded by exon 8b. (D) RT–PCR amplification of ED1 mRNA. Skin RNA from one affected and one control animal was reverse transcribed and amplified by use of a forward primer located in exon 1 and a reverse primer located in exon 5. The RT–PCR product of the affected animal corresponds to an ED1 cDNA lacking the 106-bp exon 3. The identity of the RT–PCR products and the borders of the deletion were verified by DNA sequencing (M) 100-bp-ladder; (wt) wild type; (6) affected animal No. 6 from Fig. 3A).

In conclusion, we have cloned and characterized one of the largest known genes. The bovine ED1 DNA sequences will add to our understanding of the bovine genome, in which only very limited genomic DNA information is available. Furthermore, we character-ized the molecular defect underlying anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia in cattle. These ED1 animals could serve as a valuable model for the investigation of ectodysplasin signaling in development as well as for the analysis of human anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia.

METHODS

DNA Library Screening

A bovine genomic DNA library (Zhu et al. 1999) constructed in pBACe3.6 was screened according to standard protocols (Ausubel et al. 1995). A 603-bp 32P-labeled DNA fragment of exon 9, which was PCR amplified on bovine genomic DNA, was used as probe. Positive clones were provided by the Ressource Center/Primary Database of the German Human Genome Project (http://www.rzpd.de/). To isolate the missing 5′-end of the bovine ED1 gene, the bovine BAC library RPCI42 (Warren et al. 2000) was also screened. High-density BAC filters were probed simultaneously with two probes according to the RPCI protocols (http://www.chori.org/bacpac/) with a 32P-labeled insert of the IMAGE cDNA clone IMAGp998G234997 containing 0.5 kb, corresponding to exon 1 of the human ED1 gene and a 98-bp bovine DNA fragment of exon 3, which was derived by PCR with heterologous human primers on bovine genomic DNA.

DNA Sequence Analysis

Isolated BAC DNA was restricted with appropriate restriction enzymes, and the resulting fragments were subcloned into the polylinker of pGEM-4Z (Promega). Recombinant plasmid DNA was sequenced with the thermosequenase kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and a LI-COR 4200L automated sequencer. The plasmid clones were further subcloned with different restriction enzymes. After sequencing a collection of plasmid subclones, existing gaps were closed by a primer walking strategy until both strands were completely sequenced. Sequence data were analyzed with Sequencher 3.1.1 (GeneCodes). Further analyses were performed with the online tools of the European Bioinformatics Institute (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/) and the RepeatMasker searching tool for repetitive elements (A.F.A. Smit and P. Green, http://ftp.genome.washington.edu/RM/RepeatMasker.html).

PCR Amplification and Sequencing of ED1 Exons

PCR was performed in 25-μL reactions containing 50 ng of genomic bovine DNA, 100 μM dNTPs, 10 pmole of each primer, and 2.5 units of Taq polymerase in the reaction buffer supplied by the manufacturer (QIAGEN). After a 5-min initial denaturation at 94°C, 35 cycles of 30 sec at 94°C, 1 min at the annealing temperature of the specific primer pair, and 45 sec at 72°C were performed in a MJ Research thermocycler (Biozym). Primers were designed to amplify the complete coding sequence, and all exon/intron junctions. Primer sequences and annealing temperatures are given in Table 2. The amplified products were sequenced directly by use of IRD700-labeled internal primers or standard sequencing primers on M13-tagged PCR products.

Table 2.

Primer Sequences for the Amplification of ED1 Exons

| Primer (exon)a | Sequence (5′–3′) | Length | Tm (°C) | Product (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,F | AGA GGA GCT GCA CAT GAG | 18 | ||

| 1,R | TCG AAC TTG GCT CGA GGT G | 19 | 62°C | 661 |

| 3,F | ACT GTG GAA AAG TAA TGG C | 19 | ||

| 3,R | AAT CAT AAC TTA GCT AAT GGG | 21 | 53°C | 2006 |

| 4,F | TGC CAA TAA CCT GAC TCT C | 19 | ||

| 4,R | GAC AGA TAT TTC TCA TTC CC | 20 | 52°C | 332 |

| 5,F | CAC CTC TTT AAG AGC AGG | 18 | ||

| 5,R | CCA CTA GCA CCT CCT GGG | 18 | 60°C | 496 |

| 6,F | GCA TGC CCT CTG ACT GGC | 18 | ||

| 6,R | TCT CTG GCT AAA AGC AGC CCC TG | 23 | 60°C | 262 |

| 7,F | AAC TGG TGG CTG AAC AAG C | 19 | ||

| 7,R | TTA AGG CTG TGG GTA AGG GTG G | 22 | 60°C | 189 |

| 8,F | TGG GGG TTG TGT ACA G | 19 | ||

| 8,R | TCA GCC ATT GGC TGG TCT GGG C | 22 | 60°C | 323 |

| 9,F | ACT GGT CAC CAG GGA G | 19 | ||

| 9,R | GCA CAC GGA TCA GTG AGA GTG G | 22 | 60°C | 849 |

(F) forward, (R) reverse.

cDNA Synthesis, RT–PCR

TRIZOL reagent (Life Technologies) was used to extract total RNA from bovine skin and kidney according to the manufacturer's protocol. Aliqouts of 1 μg of total RNA were reverse transcribed into cDNA by use of 20 pmole (T)24V primer and Omniscript Reverse Transcriptase (QIAGEN) in 20-μL reactions. A total of 1 μL of the cDNA was used as template in a PCR reaction. PCR assays were performed as described above.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Klippert and S. Neander for expert technical assistance. We are grateful to Johannes Buitkamp, Ruedi Fries, Ross Miller, John Lewis Williams, and the BOREALIS project for providing bovine BAC clones. This study was supported by grants from the German Fonds of the Chemical Industry FCI and the German Research Council DFG (Le 1032/4–1) to T.L.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL Tosso.Leeb@tiho-hannover.de; FAX 49-511-9538582.

Article published on-line before print: Genome Res., 10.1101/gr.182501.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.182501.

REFERENCES

- Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, NY: Wiley; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Band MR, Larson JH, Rebeiz M, Green CA, Heyen DW, Donovan J, Windish R, Steining C, Mahyuddin P, Womack JE, et al. An ordered comparative map of the cattle and human genomes. Genome Res. 2000;10:1359–1368. doi: 10.1101/gr.145900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayés M, Hartung AJ, Ezer S, Pispa J, Thesleff I, Srivastava AK, Kere J. The anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia gene (EDA) undergoes alternative splicing and encodes ectodysplasin-A with deletion mutations in collagenous repeats. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1661–1669. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.11.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drögemüller C, Neander S, Klippert H, Kuiper H, Kutschke L, Guionaud S, Ueberschär S, Scholz H, Distl O. Genetic analysis of congenital hypotrichosis with anodontia in cattle. Arch Anim Breed. 2000a;43:213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Drögemüller C, Distl O, Leeb T. Identification of a highly polymorphic microsatellite within the bovine ectodysplasin A (ED1) gene on BTA Xq22–24. Anim Genet. 2000b;31:416. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2052.2000.00693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezer S, Bayés M, Elomaa O, Schlessinger D, Kere J. Ectodysplasin is a collagenous trimeric type II membrane protein with a tumor necrosis factor-like domain and co-localizes with cytoskeletal structures at lateral and apical surfaces of cells. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2079–2086. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.11.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson BM, Brockdorff N, Formstone E, Ngyuen T, Kronmiller JE, Zonana J. Cloning of Tabby, the murine homolog of the human EDA gene: Evidence for a membrane-associated protein with a short collagenous domain. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1589–1594. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.9.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kere J, Srivastava AK, Montonen O, Zonana J, Thomas N, Ferguson B, Munoz F, Morgan D, Clarke A, Baybayan P, et al. X-linked anhidrotic (hypohidrotic) ectodermal dysplasia is caused by mutation in a novel transmembrane protein. Nat Genet. 1996;13:409–416. doi: 10.1038/ng0895-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper H, Kutschke L, Drögemüller C, Leeb T, Distl O. Assignment of the bovine ectodysplasin A gene (ED1) to bovine Xq22➞q24 by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2001;92:356–359. doi: 10.1159/000056932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monreal AW, Zonana J, Ferguson B. Identification of a new splice form of the EDA1 gene permits detection of nearly all X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia mutations. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:380–389. doi: 10.1086/301984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas FW. Genetic databases: Online catalogues of inherited disorders. Rev Sci Tech. 1998;17:346–350. doi: 10.20506/rst.17.1.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson DF, Haskins ME, Jezyk PF, Giger U, Meyers-Wallen VN, Aguirre G, Fyfe JC, Wolfe JH. Research on genetic diseases: Reciprocal benefits to animals and man. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1988;193:1131–1144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pengue G, Srivastava AK, Kere J, Schlessinger D, Durmowicz MC. Functional characterization of the promoter of the X-linked ectodermal dysplasia gene. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26477–26484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenger B, Schober S, Simon D. DUMPS cattle carry a point mutation in the uridine monophosphate synthase gene. Genomics. 1993;16:241–244. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuster DE, Kehrli ME, Ackermann MR, Gilbert RO. Identification and prevalence of a genetic defect that causes leukocyte adhesion deficiency in Holstein cattle. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:9225–9229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.9225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonstegard TS, Lopez-Corrales NL, Kappes SM, Stone RT, Ambady S, Ponce de Leon FA, Beattie CW. An integrated genetic and physical map of the bovine X chromosome. Mamm Genome. 1997;8:16–20. doi: 10.1007/s003359900339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava AK, Montonen O, Saarialho-Kere U, Chen E, Baybayan P, Pispa J, Limon J, Schlessinger D, Kere J. Fine mapping of the EDA gene: A translocation breakpoint is associated with a CpG island that is transcribed. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:126–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava AK, Pispa J, Hartung AJ, Du Y, Ezer S, Jenks T, Shimada T, Pekkanen M, Mikkola ML, Ko MSH, et al. The Tabby phenotype is caused by mutation in a mouse homologue of the EDA gene that reveals novel mouse and human exons and encodes a protein (ectodysplasin-A) with collagenous domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:13069–13074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren W, Smith TP, Rexroad CE, III, Fahrenkrug SC, Allison T, Shu CL, Catanese J, de Jong PJ. Construction and characterization of a new bovine bacterial artificial chromosome library with 10 genome-equivalent coverage. Mamm Genome. 2000;11:662–663. doi: 10.1007/s003350010126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijeratne WVS, O'Toole D, Wood L, Harkness JW. A genetic, pathological and virological study of congenital hypotrichosis and incisor anodontia in cattle. Vet Rec. 1988;122:149–152. doi: 10.1136/vr.122.7.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan M, Wang L-C, Hymowitz SG, Schilbach S, Lee J, Goddard A, de Vos AM, Gao W-Q, Dixit VM. Two-amino acid molecular switch in an epithelial morphogen that regulates binding to two distinct receptors. Science. 2000;290:523–527. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5491.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B, Smith JA, Tracey SM, Konfortov BA, Welzel K, Schalkwyk LC, Lehrach H, Kollers S, Masabanda J, Buitkamp J, et al. A 5x genome coverage bovine BAC library: Production, characterization, and distribution. Mamm Genome. 1999;10:706–709. doi: 10.1007/s003359901075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]