Abstract

The purpose of this review is to provide a better understanding for the LRP co-receptor mediated Wnt pathway signaling. Using proteomics we have also subdivided the LRP receptor family into six subfamilies, encompassing the twelve family members. This review includes a discussion of proteins containing a cystine-knot protein motif (i.e. Sclerostin, Dan, Sostdc1, Vwf, Norrin, Pdgf, Mucin) and discusses how this motif plays a role in mediating Wnt signaling through interactions with LRP.

Keywords: Wnt, Sclerostin, CCN, SOSTDC1, LRP, Mucin, DAN, Norrin, PDGF, VEGF, Cystine knot, Cystein domain, bone, CTGF, VWF, Wise, Ectodin, therapeutics, Slit

Introduction

Since its discovery nearly 30 years ago, Wnt signaling has been extensively studied for its diverse roles ranging from embryology; i.e. neuronal development & plasticity, bone development & formation, to causing diseases such as cancer(Johnson and Rajamannan, 2006; Coombs et al., 2008; Hoeppner et al., 2009). The name “Wnt” arose from the combination of the two homologous genes that were first identified in drosophila and vertebrates, namely, “wingless” and “Int”. Wingless (wg) was identified in 1980 by Nusslein-Volhard and Wieschaus as a Drosophila segment polarity gene, and their vertebrate homolog’s, INT genes, were identified in 1982 by Nusse et al (Nusslein-Volhard and Wieschaus, 1980; Nusse and Varmus, 1982).

Wnt proteins are a family of 19 conserved secreted glycoprotein’s, several of which also encode alternatively spliced isoforms, which play a critical role in all multicellular animals, including cell proliferation, migration, and morphology. Classically, Wnt proteins initiated signaling by interacting with Frizzled, a family of ten members each with seven transmembrane spanning domains. To add complexity to the pathway, Wnt has also been shown to interact with four alternate Wnt receptors; RYK (Derailed), ROR, Crypto, and LRP (Bafico et al., 2001; Forrester et al., 2004; Inoue et al., 2004; Lu et al., 2004). Derailed (RYK) and ROR are single transmembrane domain tyrosine kinase receptor. Crypto, also known as teratocarcinoma-derived growth factor 1 (TDGF-1), is a member of the EGF-CFC protein family (Salomon et al 2000). The LRP receptors belongs to the larger Low Density Lipoprotein (LDL) receptor subfamily, which are widely expressed scavengers. All of the above receptors; LRP, ROR, Crypto, and RYK are presumed to act as a tertiary complex with Wnt and Frizzled (Fzd) to influence the Wnt signaling pathway (http://www.stanford.edu/~rnusse/wntwindow.html). Signal specificity may be achieved through cell specific expression of different Fzd receptors, which are capable of forming homo- and heterooligomers or through association of Fzd receptors with different co-receptors (i.e. LRP) (Feldman and Pizzo, 1986; Gliemann et al., 1986; van Driel et al., 1987; Weisgraber and Shinto, 1991; Gong et al., 1996; Dann et al., 2001; Carron et al., 2003; Stiegler et al., 2009). Understanding how extracellular Wnt ligands interact with transmembrane receptors to modulate the intracellular signaling cascades is therefore of broad importance to biology and to human disease.

Three Wnt Signaling Cascades

There are three branches to the Wnt signaling pathway; 1) the beta-Catenin pathway (canonical pathway), 2) the planar cell polarity pathway (PCP; non-canonical), and 3) the Wnt/Ca+2 pathways. The Canonical pathway is the signaling pathway involved resulting in cancer, pattern formation, and osteogenesis to name but a few. It becomes active when Wnt ligand binds to Fzd and LRP to activate Dishevelled (Dsh) which is responsible for changing the amount of nuclear beta-Catenin. Dsh works to regulate the stability of proteins Axin, Gsk-3, and APC, which promotes the degradation of beta-Catenin (the beta-Catenin destruction complex). When Wnt activates Dsh, the beta-Catenin destruction complex is destabilized and beta-Catenin accumulates. It is thought that GSK-3 also plays a role in the formation of the Wnt, Fzd, LRP, Dsh, and Axin membrane receptor complex (Farr et al., 2000). This membrane complex leads to beta-Catenin accumulation in the nucleus where it can interact with the TCF/LEF family of transcription factors to control gene transcription (Brannon et al., 1997; Brunner et al., 1997).

The PCP pathway is distinct from the canonical Wnt pathway due to the lack of beta-Catenin involvement (Axelrod et al., 1998). Wnt signal’s through Fzd receptors to mediate asymmetric cytoskelatal organization and the polarization of cells. Within this pathway, Dsh triggers two independent pathways that are mediated through small G-proteins (GTPase) Rho or Rac. Rho requires Daam-1, whereas Rac is independent of Daam-1. Instead, Rac activates Jun Kinase (JNK) activity (Huelsken and Behrens, 2002; Habas and Dawid, 2005).

The Ca+2 pathway, not surprising, leads to the release of intracellular calcium (Arrazola et al., 2009). Here, Wnt binds Fzd and ROR, and the genes activated by this pathway are not well understood, but NFAT, PLC, PKC, all appear to be involved. This pathway is important for cell adhesion and movements during gastrulation (Habas and Dawid, 2005; Kohn and Moon, 2005). Adipogenesis, calcium homeostasis, and apoptosis are examples of processes regulated by non-canonical Wnt signaling.

Receptor - Ligand Presentation

The way in which a ligand is presented to its receptor has critical consequences to a ligand’s ability to transduce a signal. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) are major constituents of the extracellular matrix, which are implicated in the pathophysiology of diseases, including cancer, in which signals and tissue interactions malfunction (Selva and Perrimon, 2001; Nybakken and Perrimon, 2002). HSPGs, such as Glypicans and Syndicans, are soluble and membrane-intercalated proteins, which are composed of a core protein, decorated with covalently linked heparan sulfate (HS) chains (Bernfield et al., 1999). In Drosophila and mammalian systems, mutants that are completely deficient in HS sulfation have disrupted Wnt signaling (Reichsman et al., 1996; Lin et al., 1999; Toyoda et al., 2000; Dhoot et al., 2001). Since Wnt signaling is controlled by HS sulfation, the sheer presence of Wnt ligand is not sufficient to assume Wnt pathway function. The ability of Wnt to transduce a signal is dependent on its proper presentation by HSPG to either or both Fzd and its coreceptors, i.e. LRP.

LRP Family

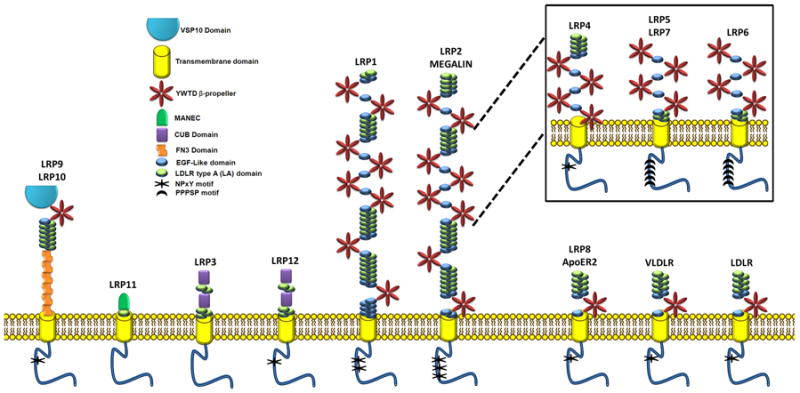

In 1999, the LDL-receptor family was composed of five mammalian proteins and was thought to mainly mediate endocytosis. Today there are a total of twelve members of the LDL-receptor family and their functional roles are quite diverse and have yet to be fully understood (Table 1 & Figure 1). LRP4 and LRP11 were identified during our research for this review, on the basis of their protein sequence homology. All LRP receptors are type I transmembrane protein receptors (C-terminus in cytosol), with the exception of LRP4 which appears to have its amino terminus in the cytosol and thus a Type II transmembrane protein receptor (Figure 1). An additional feature that the LDLR family shares is the highly conserved extracellular LDLR ligand binding repeat (LA, or complement-type cysteine rich repeat – shown as a green oval in Figure 1). Most members of the family also share several structural features such as (a) epidermal growth factor (EGF)-precursor homology domains (blue ovals in Figure 1), which themselves are composed of EGF repeats (cysteine-rich class B repeats) and spacer domains with YWTD propeller repeats (red propellers in Figure 1), and mediate the acid-dependent dissociation of the ligands from the LDL receptor and (b) an O-linked sugar domain; and (c) an intracellular NPXY (or FXNPXY) sequence(s). LRP receptors also contain a putative cytoplasmic dishevelled (DSH) protein domain which is specific to the signaling protein dishevelled (MotifFinder IPB003351A). This domain is found adjacent to the PDZ domain (PF00595) and often in conjunction with both DEP (PF00610) and DIX (PF0778) (Theisen et al., 1994). The presence of the putative DSH domain located in the cytoplasmic tail of LRP makes one question whether DSH also interacts with LRP. If this is so, there may be more LRP receptors acting as Wnt co-receptors, than just LRP5 & 6.

Table 1.

LDLR protein family members. Five LDLR receptors were identified before 1999, and today there is a total of 12 family members (new members are shown shaded in grey). All, but LRP4, are Type I transmembrane protein receptors. LRP4 is a Type II transmembrane protein receptor. LRP4 and LRP11 were identified on the basis of protein sequence homology.

| 1999 Nomenclature | 2009 Nomenclature |

|---|---|

| VLDLR | VLDLR |

| LDLR | LDLR |

| LRP (A2MR; alpha 2 macroglobulin receptor) | LRP1 |

| Megalin | LRP2 |

| LRP3 | |

| LRP4 | |

| LRP5 | |

| LRP6 | |

| ApoER2 | LRP8 |

| LRP9 (LRP10, SORL1) | |

| LRP11 | |

| LRP12 |

Figure 1.

LRP family schematic. Note LRP4 is inverted for the simplicity of the diagram.

Of the Several unique structural features which distinguish the LRP family, six subfamilies are discernable (I-VI; Table 2). The first (I) consisting of the LDLR, VLDLR, and ApoER2 (LRP8) with seven LA domains, three EGF-like domains, and one YWTD propeller. The second (II) subfamily consists of LRP1 and LRP2, and their soluble isoforms (Quinn et al., 1997). These two receptors have the largest extracellular domains each with eight YWTD propellers spaced by EGF and LA domains. LRP4, LRP5, and LRP6 (third family, III) carry high sequence homology to a region within LRP1, YWTD repeat three through six. This suggests that LRP4, 5, and 6 may have evolved from LRP subfamily II, with LRP4 undergoing a genomic inversion event. In addition to the sequence homology evidence suggesting LRP5 and 6 having evolved from LRP subfamily I, these receptors also share some of the same ligands (i.e. CTGF). LRP12 and LRP3 are the only receptors with CUB domains (CUB is from “complement C1r/C1s, Uegf, Bmp1” functions during embryogenesis) and compose the fourth (IV) subfamily. The unique LRP9 with six fibronectin domains (Fn3) makes up the fifth (V) subfamily, and the sixth (VI) subfamily consists of LRP11 possessing the only MANEC domain (a domain with eight conserved cysteines). The MANEC domain was previously named MANSC and is found in the N terminus of higher multicellular animal membrane and extracellular proteins. It is postulated that this domain may play a role in the formation of protein complexes involving various protease activators and inhibitors.

Table 2.

A table showing the different members of each LRP subfamily.

| LRP Subfamily | Members |

|---|---|

| I | LDLR, VLDLR, ApoER2 (LRP8) |

| II | LRP1, LRP2 |

| III | LRP4, LRP5 (LRP7), LRP6 |

| IV | LRP12, LRP3 |

| V | LRP9 (LRP10) |

| VI | LRP11 |

LDLR has a well characterized role in the regulation of cholesterol metabolism. LRP1 and LRP2 (Megalin) are multifunctional and bind a diverse group of ligands, including ApoE. LRP1 has also been shown to interact with Fzd1 to down-regulate Wnt signaling (Zilberberg et al., 2004a). VLDLR, LRP8, and LRP9 can bind ApoE; and LRP8 and VLDLR bind Reelin. Reelin activates the tyrosine kinases and subsequent phosphorylation of the PTB protein (phosphotyrosine binding) domain containing adaptor protein (Dab1) in migrating neurons (Herrick and Cooper, 2004). LRP3 and LRP12 bind integrins and golgi associated proteins. The second best studied subfamily of LDL receptors is LRP5 and LRP6, which bind Wnt, Sclerostin, Wise, Dkk, and CTGF to name a few. Importantly, at the 2009 ASBMR meeting this past September, Leupin et al. (Novartis) presented results demonstrating that LRP4 is indeed capable of mediating WNT inhibition during bone formation (ASBMR 2009). The subfamilies have been shown to dimerize with, as homo or heterodimers, other LRP receptors within the family. For example, LRP6 forms inactive homodimers at the cell surface that are mediated through the extracellular EGF-like repeats (Liu et al., 2003), upon Wnt binding, this allosteric inhibition is relieved and an intracellular conformational switch leads to LRP6 activity.

Interestingly, WNT is not the only ligand for the Frz-LRP6 complex, Spondin (structurally similar to Mindin) which has a Reelin domain, also interacts with FZ & LRP6 (Nam et al., 2006). This interaction with R-Spondin takes place in the second YWTD propeller of LRP6, similar to Wnt, Wise and Sclerostin. However, R-Spondin synergizes with Wnt to stimulate activity, and this activity can also be inhibited by Dkk1 (presumably Sclerostin and Wise also) (Kim et al., 2008). LRP subfamily 1 (ApoER2, VLDLR, LDLR) have also been shown to bind Reelin, but there have been no reports on their participation in Wnt signaling (May et al., 2005). In addition, one has to wonder if other LRP6 subfamily members (LRP5 and LRP4) bind Reelin and/or Spondin. Reelin is a large extracellular glycoprotein (Balthazart et al., 2008) similar to the Mucin family that contains a cystine knot protein motif (CK domain), and may function to stabilize receptor dimmers (Tan et al., 2008).

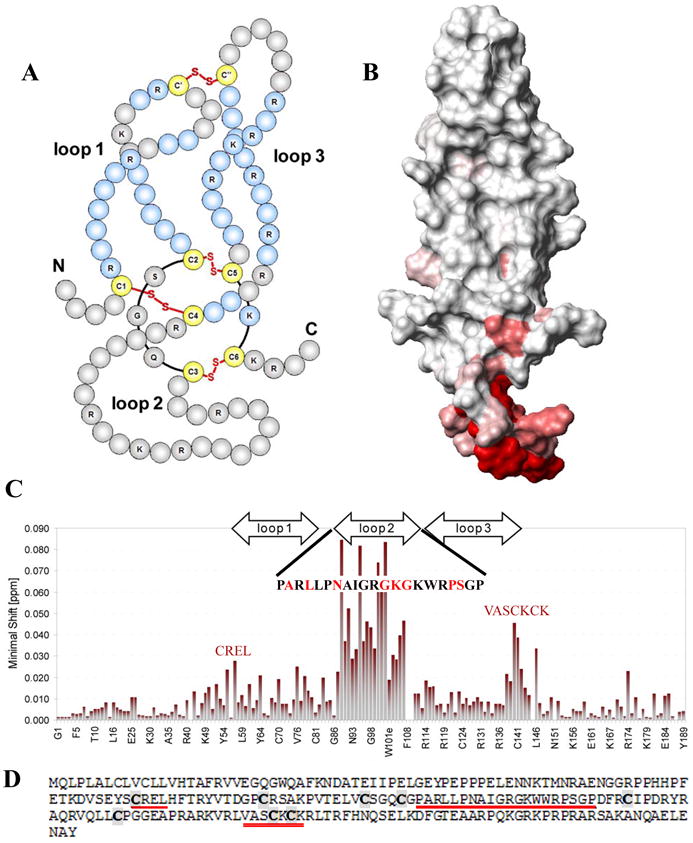

The Cystine-Knot

The cystine-knot (CK) is a highly conserved protein motif found in many growth factors and other proteins as discussed above. The cysteine residues which form disulphide bridges are important in directing and maintaining the secondary and tertiary protein structure (Figure 2D; grey boxes). A mutation in any of the cysteine residues or change in amino acid spacing would result in an incorrectly folded protein. This incorrectly folded protein would then result in the proteins’ inability to bind to its target (LRP) receptor and modulate signaling. In turn altering downstream gene expression required for normal cellular function. Changes to this “normal” cellular function may result in an altered or possible diseased, cellular and tissue function.

Figure 2.

Published structure of Sclerostin protein in solution. A: Schematic representation of the structure. B: Contact surface view. C: Back-bone amide chemical shift observed for the Sclerostin blocking monoclonal antibody binding to Sclerostin (amino acid sequence with high binding is displayed). D: Amino acid sequence of Sclerostin. Loop 2 displays the highest level of binding activity. The amino acid displaying high binding activity are shown in red, and cysteine residues are bolded in grey boxes. Modified from Veverka et al. (2009).

Interaction with LRP

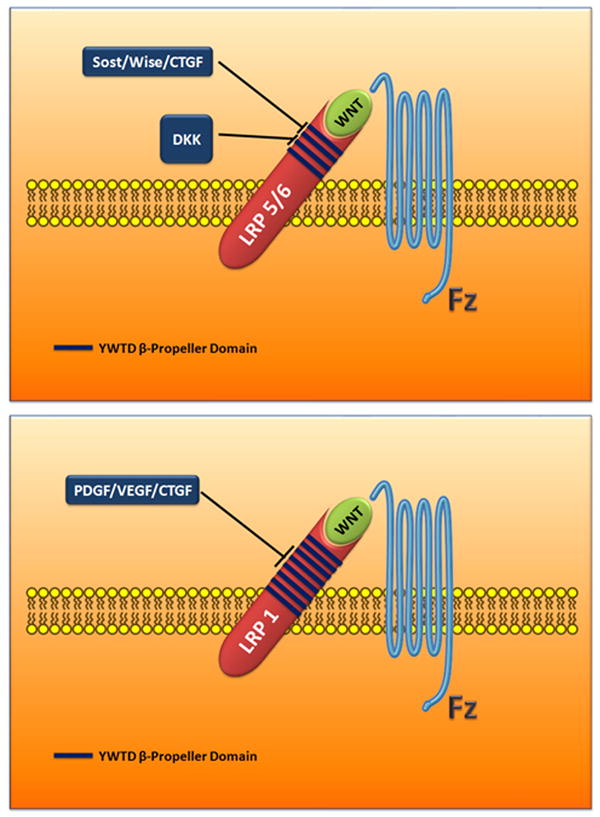

Studies have now conclusively shown that many members of the above subfamilies do interact directly with LRP5 or LRP6 to modulate Wnt signaling. The best characterized interactions are those from Sclerostin, Wise, and the CCN family member, CTGF (Figure 3). The one common characteristic these proteins share is their cystine-knot domain (CK domain). Deletion of this CK domain or mutation of any one of its cysteine residues results in its inability to bind LRP resulting in altered Wnt signaling (Itasaki et al., 2003; Mercurio et al., 2004). Mercurio et al (2004) used CTGF protein modules deletions to report that it was the CK domain which was necessary for its interaction with LRP6 to inhibit Wnt signaling. The ability of Mucin, CCN, DAN, Norrin, PDGF cystine-knot subfamilies to modulate Wnt and their possession of a CK domain begs the question of whether they also are able to directly interact with LRP5 or LRP6. Alternatively, since CTGF has been shown to bind to the LRP6 and LRP1 subfamily, can Sclerostin, Wise, PDGF, Norrin, CCN, or other cystine-knot proteins also bind to the LRP1, and other LRP subfamilies?

Figure 3.

Schematic showing the interaction domains between LRP/Fzd, Wnt, and WISE/Sclerostin Cystine-knot protein family. Dkk cysteine-rich domains do not share high enough homology to the Wise/Sclerostin family.

CTGF/PDGF/VEGF all bind to the sequence region on LRP1, which is homologous to the Sclerostin/wise/CTGF region in the LRP III subfamily.

Cystine-Knot Motif Proteins: Interaction With The Wnt Pathway

Sclerostin (Sost)/Wise (Ectodin; SOSTDC1; Usag1) Subfamily

The discovery of the human SOST (Sclerosteosis) gene is a triumph for the study of human genetics. Sclerosteosis and Van Buchem diseases are rare sclerosing bone dysplasias, discovered more than 40 years ago by Hansen (1967) , and are inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion (Hansen et al., 1967). Each disease is manifested by a greatly increased amount of bone mass, with Sclerosteosis being the most severe (Beighton, 1976; Beighton et al., 1976a; Beighton et al., 1976b; Beighton et al., 1977a; Beighton et al., 1977b; Balemans et al., 2001; Brunkow et al., 2001). Positional cloning revealed that both diseases are caused by a loss of function of the human SOST gene (Brunkow et al., 2001). Sclerosteosis is the result of point mutations causing either a termination or frame shift during protein translation. Alternatively, Van Buchem results from a 52K genomic deletion, 35Kb downstream of SOST, which contains certain regulatory sequences responsible for regulation of Sost gene expression (Loots et al., 2005).

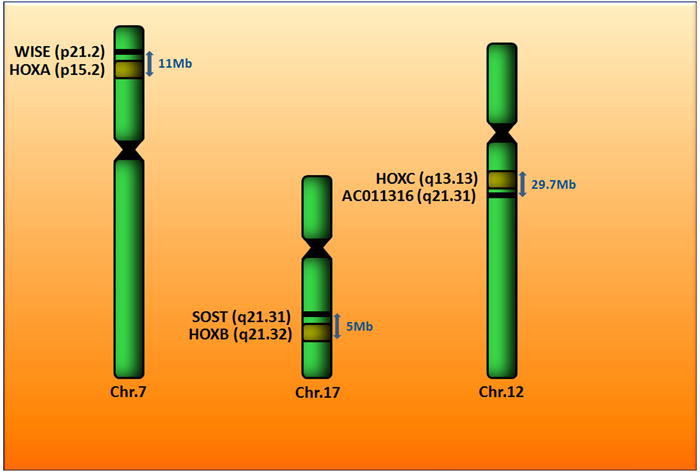

WISE (Ectodin, SOSTDC1, and USAG-1) was originally identified as a modulator of avian Hox gene expression. Hox genes are key regulators in anterio-posterior patterning (Itasaki et al., 2003). WISE maps to human chromosome 7p21.1, 10.6 Mb downstream of the HOXA cluster (Figure 4). In a search for Wise family members, Ellies et al (2006) found that SOST maps to chromosome 17q21.31, 5 Mb downstream of the HOXB complex (Ellies et al., 2006) (Figure 4). Both loci have a similar structure and, in combination with their linkage to HOX complexes, seem to have arisen by duplication and divergence from a common ancestral chromosome region. Using Ensembl to search for genomic similarity to SOST or Wise, other putative family members, linked to the HOXC and HOXD complex are yet to be identified. Human contig sequence AC011316 found at 12q13.11 is linked to HOXC and is 63% homologous to exon 2 of SOST (Figure 4). At this time, it is unknown if this sequence encodes a functional protein. An important question is whether other sequences exist that are homologous to SOST or WISE.

Figure 4.

Schematic showing the chromosomal locations of Wise and SOST, alongside their HOX clusters.

Based on their weak protein sequence similarity to the DAN and CCN family of cystine-knot proteins, which themselves bind BMPs, Sclerostin (protein product of the SOST gene) was initially postulated to exert its function via its biochemical ability to bind and inhibit BMP signaling (Brunkow et al., 2001; Kusu et al., 2003; Winkler et al., 2005; Ellies et al., 2006). In cell culture models, using alkaline phosphatase activity as a late marker for BMP-mediated osteoblast differentiation, Sclerostin was found to inhibit BMP6 but not BMP4. In ATDC-5 cell assay, Wise did not inhibit BMP6 and only weakly influenced BMP4- dependent activity at very high concentration (Ellies et al., 2006). Therefore, Wise has a preference for inhibiting BMP7, BMP2, and BMP4, and more weakly, BMP6. Despite the significant homology between Wise and Sclerostin, they are not identical in their functional ability to inhibit BMP signaling.

Both Wise and Sclerostin function to inhibit Wnt signaling in in-vitro assays by binding to YWTD propeller 1 & 2 of LRP5 or LRP6 (Ellies and Krumlauf, 2002; Itasaki et al., 2003). Wise, but not Sclerostin, also acts as a stimulator, or conversely a mild repressor, of the Wnt pathway (Ellies and Krumlauf, 2002; Itasaki et al., 2003). Biochemical competitive studies have revealed that Wise has a higher affinity, than Wnt, for LRP6 (Itasaki et al., 2003). It remains unclear if 1) Sclerostin and Wise can bind simultaneously to LRP and 2) which of the ligands (CTGF, Sclerostin, Wise, DKK, Wnt) contain the highest affinity for LRP5 and LRP6, the LRP3-subfamily. A recent study has very nicely shown that BMP/BMPR1A can effectively repress 90% of SOST gene expression, which ultimately results in the activation of the canonical Wnt pathway (Kamiya et al., 2008).

Like its closest family member, Sclerostin, Wise encodes a 200 amino acid, 28kDa, secreted protein containing a leader sequence and a cysteine rich protein domain (CK domain; Figure 5; SMART domain SM00041). Proteins containing this CK domain are structurally related and share a common overall topology. These proteins have very little overall sequence homology, but they all have an unusual arrangement of six cysteines linked to form a “cystine-knot” conformation (Ellies et al., 2006). The active forms of these proteins are thought to be dimers, either homo- or heterodimers. Because of their shape, there appears to be an intrinsic requirement for the cystine-knot growth factors to form dimers. This extra level of organization increases the variety of structures built around this simple structural motif (Figure 2A, B).

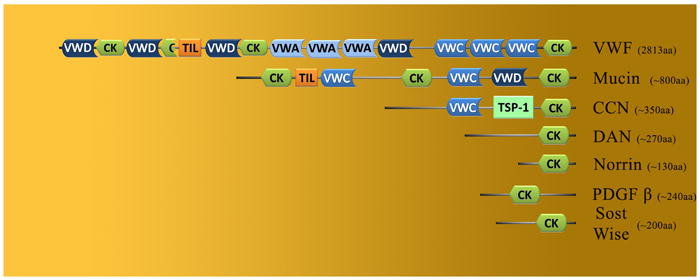

Figure 5.

Schematic showing an alignment of highly conserve protein domains from cystin-knot proteins most homologous to Sclerostin and Wise.

Significant similarity exists within the cystine-knot motifs from DAN (Cerberus, DAN, Gremlin, Caronte), CCN (NOV, CTGF, Cyr61), Slit, and Mucin family members (CK domain, Figure 5). There is also homology to the cysteine motifs in individual genes, such as Von Willderbrand Factor (VFW), PDGF, and Norrie Disease Protein (NDP) (Figure 5). They all contain a consensus organization of eight core cysteine residues and one glycine residue (between cys-3 and cys-4) (Ellies et al., 2006). In contrast to Wise and Sclerostin, the other subfamilies contain one to two additional cysteine (cys) residues between cys-4 and cys-5 of the core motif (Ellies et al., 2006). The cystine-knot domain is the only recognizable motif found in the Wise/Sclerostin, Norrie and DAN subfamilies, whereas members of the other groups contain multiple motifs, such as insulin binding, Von Willderbrand, and TSP1 domains.

CCN Subfamily

The first family member for this subfamily was discovered in 1985 by Lau and Nathans, these proteins are 30-40kDa and extremely cysteine rich (10% by mass), and multimodular (Brigstock, 1999; Perbal, 2001). The CCN family includes Cysteine-rich 61 (Cyr61/CCN1), Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CTGF/CCN2), Nephroblastoma Overexpressed (NOV/CCN3), and Wnt Induced Secreted Proteins-1 (Wisp-1/CCN4), -2 (Wisp-2/CCN5) and -3 (Wisp-3/CCN6). The function of the protein domain modules is not well understood (Figure 5). Module 1 is insulin-like growth factor binding domain, module 2 is a Von Willebrand type C domain, module 3 is a thrombospondin-1 domain, and module 4 is a C-terminal domain containing a putative cystine-knot. These proteins all can stimulate mitosis, adhesion, apoptosis, extracellular matrix production, growth arrest, and migration (hormone action, skeletal growth, placental angiogenesis, and diabetes induced fibrosis). Many of these activities are born from their ability to bind and activate integrins. However, it has also been reported that CTGF/CCN2 can also bind to either LRP1 or LRP6 (Segarini et al., 2001; Gao and Brigstock, 2003; Mercurio et al., 2004). Mercurio (2004) showed very elequently that the C-terminal (CK domain), domain 4, of CTGF that interacted with LRP6 to inhibit Wnt signaling. This demonstrates that domain 4 (CK domain) of the CCN family may have a role in regulating the Wnt pathway through its interaction with the LRP receptors. It is also interesting that module 3 contains a thrombospondin-1 domain. As we discussed above, Spondin interacts with the LRP 5/6 subfamily, and Spondin is a family member to thrombospondin. Could this thrombospondin-1 domain also interact with the LRP receptors?

DAN Subfamily

The DAN subfamily is an evolutionary conserved group of proteins that function as transforming growth factor (TGF) Beta or BMP antagonists. Gremlin was the first member of this group that was identified in 1998 by Hsu et al (Hsu et al., 1998). The subfamily is made up of the following genes; Dan (differential screening-selected gene aberrative in neuroblastoma), Cerberus, Gremlin, PRDC, and several other genes that have only been identified as expressed sequence tags. They have a very important role during development of the embryo, with that said; little is known about their biological role in the adult body plan. This protein family shares a cysteine-rich domain (the CK domain) and has much resemblance to the Mucins, a family of secreted factors found in mucus (Figure 5). It is unclear whether the similarity to Mucin is functionally meaningful. One family member, Cerberus, finds itself apart from the rest of the Dan subfamily, due to its unique ability to inhibit Wnt signaling. It remains unclear if this ability to inhibit Wnt signaling may involve an interaction between its CK-domain and LRP receptor.

Mucin/Slits Subfamily

The Mucin subfamily contains 10 proteins; MUC1 (Mucin 1 transmembrane), MUC2 (Mucin 2), MUC4 (Mucin 4), MUC5AC (gastric), MUC6 (Mucin 6 gastric), MUC7 (Mucin 7 salivary), MUC13 (Mucin 13, epithelial transmembrane), MUC16 (Mucin 16), MUC19 (Mucin 19), and OVGP1 (Oviductal glycoprotein 1). Mucins are high molecular weight glycoprotein’s that are secreted by epithelial tissues. Indirect evidence suggests that these genes might encode the core protein of parasite Mucins, proposed to be involved in the interaction with, and invasion of, mammalian host cells. The subfamily harbors three repeated protein domains (Figure 5). The first is a VWD domain and it is involved in multimerisation of proteins, the second is the CK domain containing 8 conserved cysteine residues, and the third is the TIL domain, which consists of ten cysteine residues making 5 disulfide bonds. The N and C termini are conserved between all members of the family, whereas the central region is not well conserved but containing a large number of threonine residues which can be glycosylated. Recent evidence points to the abilility of MUC to modulate the Wnt pathway though an interaction with the intracellular Wnt machinery, B-Catenin.

Members of the Slit protein family share a number of structural features with Mucins, such as the N-terminal leucine-rich repeats, the C-terminal epidermal growth factor-like motifs, and the cysteine rich (CK) domain. The entire family of five rat and human Slit genes encode for a 1523-1530 amino acid protein. Signaling by these proteins requires the presence of heparan sulfate chains (Hu, 2001). Last year, Prasad et al (Prasad et al., 2008) show for the first time that Slit has the capacity to modulate Wnt signaling via the modulation of Beta-Catenin.

Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF)

PDGF is a growth factor that plays a significant role in controlling blood vessel formation (angiogenesis) from already existing blood vessel tissue. Uncontrolled angiogenesis is due to uncontrolled PDGF, is a trait of cancer. The PDGF subfamily was for more than 25 years assumed to consist of only PDGF-A and –B, however, with the recent discovery of members PDGF-C and PDGF-D, the subfamily is composed of four members. With little information on PDGF-C and -D protein structures to confirm or debate from, PDGF-C protein appears to resemble VEGF-A structurally. The classical PDGF polypeptide chains, PDGF-A and PDGF-B, are well studied and they regulate a number of processes via two receptor tyrosine kinases, PDGF receptors α and β. In addition to their ability to bind to PDGF receptors, PDGF-B has also been reported to bind to LRP1, and Zilberberg et al (2004) reported that LRP1 is able to downregulate Wnt signaling by interacting with Fzd (Zilberberg et al., 2004b). The interaction of PDGF with LRP has no apparent link, as of yet, to the Wnt signaling pathway. However, a recent study by Cohen et al (2009) has reported a correlation between the expression of Wnt7a and the expression of PDGFR-A and –B (Cohen et al., 2009). It is intriguing that PDGF proteins contain a CK domain similar to those from Sclerostin, Wise, and CTGF, and that PDGF-B has been shown, like CTGF, to interact directly with LRP1. However, it is yet to be determined whether PDGF has the ability to interact with LRP to modulate Wnt signaling (Figure 5).

Norrin

The Norrin protein is involved in Norrie Disease, an X-linked recessive disorder resulting in an incomplete development of retinal vasculature. Norrie Disease Protein (NDP) was originally discovered over a decade ago and named EVR2 (Toomes et al., 2004). Many retinopathies are classified as NDP-related; persistent fetal vasculature syndrome (PFVS), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), Coats disease, and X-linked familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (X-linked FEVR). Norrie disease results from either point mutations or deletions, 70% of which affect a cysteine residue.

The Norrie gene encodes a small secreted 133 amino acid protein termed norrin. The norrin protein contains only one protein domain, the cystine-knot (CK domain), which is encoded from exon 2 and exon 3 (Figure 5). The cystine-knot is involved in the formation of covalently-linked dimers, which ultimately leads to pathway activation. Norrin acts as a activator for the Wnt pathway through its interaction with Fzd4 and LRP5 or LRP6 (Xu et al., 2004). Yet the exact nature of this interaction with LRP5 or LRP6 is not clearly understood. The possibility that Norrin may interact directly with LRP has been tainted by studies showing that it was unable to bind LRP6. This does not omit the possibility that Norrin may bind to LRP5, as patients with mutations in LRP5 also present with vascular eye defects.

Von Willebrand factor (VWF)

VWF is a glycoprotein involved in hemostasis. As a monomer, VWF is a 2050 amino acid protein with five specific domains (Figure 5). The first is the VWD domain, which binds to coagulation factor VIII; the second, the VWA domain binds to the platelet GPI b-receptor, heparin, and possibly collagen. The third is the VWC domain that binds to platelet integrin αIIbβ3. The fourth is the “cystine knot” domain (CK), and the last fifth domain is the TIL domain, which consists of ten cysteine residues making 5 disulfide bonds. VWF monomer proteins are subsequently N-glycosylated, and multimerize into functional proteins consisting of more than 80 subunits of 250kDa each making the multimer >20,000kDa. VWF protein contains domains that help in the making of blood clots. VWF is made in the endothelial cells that line the inside surface of blood vessels and bone marrow cells. VWF helps platelets stick together and adhere to the walls of blood vessels at the side of an injury. VWF also carries coagulation factor VIII to the area of the clot formation. No link to the Wnt pathway has been made as of today. Yet, coagulation factor VIII, that binds to VWD domain, is known to interact with LRP to help in its clearance from the plasma (Lenting et al., 1999). No link to Wnt signaling has been made as of today.

Therapeutics/Diseases

Seminal discoveries have uncovered the importance of the Wnt signaling pathway during development, cell biology and physiology. The importance of this pathway is reflected in the growing number of human diseases that are the consequence of mutations within the Wnt signaling pathway or its abnormal modulation, to cause abnormal Wnt signaling. Twenty three human diseases have been associated with mutations in Wnt pathway (Table 3). This number is small considering that there are 19 Wnt and 10 Fzd proteins.

Table 3.

Diseases associated with mutations within genes of the Wnt signaling pathway.

| Gene | Disease |

|---|---|

| APC | - Polyposis coli (Kinzler et al., 1991; Nishisho et al., 1991) |

|

| |

| LRP5 | - Bone Density (van Meurs et al., 2008) |

| - Vascular defects in the eye (Osteoperosis-pseudoglioma Syndrome, OPPG) (Gong et al., 2001; Boyden et al., 2002; Little et al., 2002) | |

|

| |

| LRP5 | - Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy (Toomes et al., 2004; Qin et al., 2005) |

|

| |

| LRP6 | - early coronary disease (Mani et al., 2007) |

|

| |

| LRP6 | - Osteoporosis (Mani et al., 2007) |

|

| |

| LRP6 | - Late onset Alzheimer (De Ferrari et al., 2007) |

|

| |

| FZD4 | - Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy: retinal angiogenesis (Robitaille et al., 2002; Qin et al., 2005) |

|

| |

| Norrin | - Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy (Xu et al., 2004) |

|

| |

| WNT3 | - Tetra-Amelia (Niemann et al., 2004) |

|

| |

| WNT4 | - Mullerian-duct regression and virilization (Biason-Lauber et al., 2004) |

|

| |

| WNT4 | - SERKAL syndrome (Mandel et al., 2008) |

|

| |

| WNT5B | - Type II diabetes (Kanazawa et al., 2004) |

|

| |

| WNT7A | - Fuhrmann syndrome (Woods et al., 2006) |

|

| |

| WNT7A | - Al-Awadi/Raas-Rothschild/Schinzel Syndrome (Woods et al., 2006) |

|

| |

| WNT10A | - Odonto-onycho-dermal dysplasia (Adaimy et al., 2007) |

|

| |

| WNT10B | - Obesity (Christodoulides et al., 2006) |

|

| |

| WNT10B | - Split-Hand/Foot Malformation (Ugur and Tolun, 2008) |

|

| |

| AXIN1 | - caudal duplication (Oates et al., 2006) |

|

| |

| TCF7L2 (TCF4) | - Type II diabetes (Florez et al., 2006; Grant et al., 2006; O’Rahilly and Wareham, 2006) |

|

| |

| AXIN2 | - Tooth agenesis (Lammi et al., 2004) |

|

| |

| DACT1 | - Adipogenesis (Lagathu et al., 2009) |

|

| |

| WTX | - Wilms tumor (Major et al., 2007; Rivera et al., 2007) |

| - sclerosing skeletal dysplasia (Jenkins et al., 2009) | |

|

| |

| PORC1 | - Focal dermal hypoplasia (Grzeschik et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007) |

|

| |

| WIF | - Osteosarcoma (Kansara et al., 2009) |

|

| |

| RSPO4 | - autosomal recessive anonychia (Bergmann et al., 2006; Blaydon et al., 2006) |

|

| |

| VANGL1 | - Neural tube defects (Kibar et al., 2007) |

|

| |

| SOST | - Bone Density (Brunkow et al., 2001) |

In addition to Wnt and Fzd, Wnt co-receptors like LRP5 and LRP6 have genetic diseases associated with them. Human mutations in LRP5 causes bone density effects, eye vascular effects, and FEVR (Table 3). HLRP6 mutations cause early onset coronary disease, osteoporosis and late onset Alzheimer’s, and Increased LRP5/LRP6 is associated with colon cancer (Table 3). Mutations in the SOST gene cause bone density effects. This list will increase once our understanding of the role of the other (ROR, RYK, and Crypto) Wnt co-receptors is advanced.

In addition to the genetic mutations described above, other diseases have been linked to the uncontrolled “abnormal” signaling of the Wnt pathway. Increased levels of Fzd are associated with gastric cancer, leukemia, kidney cancer, and liver cancer. The intracellular Wnt pathway components comprise beta-Catenin, APC, Axin, and GSK-3. Human genetic mutations in APC impair beta-Catenin degradation or in beta-Catenin itself which stabilizes beta-Catenin, both result in constitutively active Wnt signaling and have been linked to familial adenomatous olyposis and cancer (colon, desmoid, endometrial, gastric – intestinal, hepatocellular, kidney – wilms tumor, lung, medulloblastoma, melanoma, ovarian, pancreatic, pilomatricoma, prostate, esophageal, thyroid, and uterine) (Baehs et al., 2009; Barker et al., 2009; Bisson and Prowse, 2009; Bjorklund et al., 2009; Cheah, 2009; Chung et al., 2009; Han, 2009; Hirata et al., 2009; Jiang et al., 2009; Lu et al., 2009; Monga, 2009; Wang et al., 2009; Yamamoto et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2009). There has also been an association of hepatocelluar carcinoma with mutations in human Axin. Reduced Wnt signaling has been observed in the transition from hypertrophy to failing heart (Schumann et al., 2000).

With diseases comes a therapy. In Table 4, one can peek at what is being developed for commercial therapeutics around the Wnt pathway. Table 4 separates the therapeutics into twenty intracellular and eight extracellular Wnt therapies. A therapeutic is categorized in one of two pools; 1) a biologic (protein or antibody) or 2) a small molecule. The Wnt extracellular therapeutics consists of seven biologic and three small molecules, whereas the intracellular therapeutic area is vastly dominated by small molecule therapeutics. The apparent focus is centered around the intracellular GSK3 target, 83% of the small molecule technology surrounds inhibiting GSK-3. However, potential problems exist with the long term use of GSK3 inhibitors. GSK3 inhibitors would be expected to mimic the overexpression of Wnt signaling and therefore may become oncogenic.

Table 4.

Wnt Modulators in the Biotech Pipeline

| Company | Therapeutic | Pathway Target | Technology | Development Stage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Modulators | |||||

| Cancer | Nuvelo | Nu206 | r-Spondin | Biologic | Preclinical |

| Bone | Nuvelo | LRP5 Mab | LRP5 | Biologic | Discovery |

| Bone | Nuvelo | Dkk1 Mab | Dkk1 | Biologic | Discovery |

| Cancer | Fibrogen | CTGF Mab | CTGF | Biologic | Preclinical |

| Bone | Amgen | Sclerostin Mab | SOST | Biologic | Phase II |

| Bone | Novartis | Sclerostin Mab | SOST | Biologic | Preclinical |

| Bone | Eli Lilly | Sclerostin Mab | SOST | Biologic | Preclicnial |

| Cancer | Wyeth | WAY-316606 | SFRP | Small Molecule | Preclinical |

| UTSW | Niclosamide | Frizzled | Small Molecule | Discovery | |

| Bone | Enzo Biochem | Small Mole NCI | Dkk | Small molecule | Preclinical |

| Bone, cancer | OsteoGeneX | Anti-Sclerostin | SOST/LRP | Small molecule | lead opt, preclinical |

| Bone | Galapagos | wnt pathway | LRP5 | Small molecule | Discovery |

| Intracellular Modulators | |||||

| Cancer | Novartis | XAV939 | tankyrase 1/Axin | Small molecule | Discovery |

| Cancer | UTSW | IWR | Axin | Small molecule | Discovery |

| Asahi Kasei Corporation | IQ1 | PP2A | Small molecule | Discovery | |

| Cancer | Scripps | QS11 | ARFGAP1 | Small molecule | Discovery |

| Cancer | St. Jude Children’s | NSC668036 | Dsh | Small molecule | Discovery |

| Diabetes | SmithKline Beecham | SB-216763 | GSK3 | Small molecule | Abandoned |

| Diabetes | SmithKline Beecham | SB-216763 | GSK3 | Small molecule | Abandoned |

| Stem cell renewal | Rockefeller | BIO(6-bromoindirubin- 3’-oxime) | GSK3 | Small molecule | Discovery |

| Cancer | Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center | DCA | beta-catenin | Small molecule | Discovery |

| Scripps/Novartis | (methylenedioxy)benzyl-amino]-6-(3- | unknown | Small molecule | Abandoned | |

| Cancer | Wyeth | 2,4-diamino-quinazoline | TCF/beta-catenin | Small molecule | Lead Optimization |

| Cancer | Seoul National University | Quercetin | TCF | Small molecule | Abandoned |

| Cancer | Institute for Chemical Genomics | ICG-001 | CREB-binding protein | Small molecule | Abandoned |

| Cancer | Dana Farber | several other | TCF/beta-catenin | Small molecule | Abandoned |

| Cancer, Bone, Obesity | OsteoGeneX | wnt pathway | various wnt pathway | Small molecule | lead opt, preclinical |

| Cancer | Avalon | AVN316 | Bcatenin | Small molecule | lead candidate selected |

| Cancer | Curis | wnt pathway | Wnt pathway | Small molecule | Discovery |

| Cancer | Celon | WNT | RNAi | ||

| Cancer | Ethical Oncology | wnt pathway | BCL-beta-catenin | lead optimization | |

| Alzheimers | Neuropharma SA | wnt pathway | gsk3 inhibit | Small molecule | phase I |

| Diabetes | DeveloGen AG | wnt pathway | gsk3 inhibit | Small molecule | preclinical |

| Diabetes | Eli-Lilly | wnt pathway | gsk3 inhibit | Small molecule | preclinical |

| Bone | Roche | wnt pathway | gsk3 inhibit | Small molecule | preclinical |

| Cancer | Deciphera | wnt pathway | gsk3 inhibit | Small molecule | preclinical |

| Diabetes | Crystal Genomics | wnt pathway | gsk3 inhibit | Small molecule | preclinical |

| Diabetes | Cyclacel | wnt pathway | gsk3 inhibit | Small molecule | preclinical |

| Neuro, Metabolic, Pain | Amphora | wnt pathway | gsk3 inhibit | Small molecule | preclinical |

| Diabetes | Kemia | wnt pathway | gsk3 inhibit | Small molecule | preclinical |

| Diabetes | Chiron | wnt pathway | gsk3 inhibit | Small molecule | preclinical |

| Alzheimers | AstraZenica | wnt pathway | gsk3 inhibit | Small molecule | phase I- Discontinued |

| Alzheimers, Diabetes | Mitsubishi | wnt pathway | gsk3 inhibit | Small molecule | preclinical - no dev since 2007 |

| All Indications | Xcellsyz | wnt pathway | gsk3 inhibit | Small molecule | preclinical- no dev since 2005 |

| Diabetes, Cancer | Kinetek Pharma | wnt pathway | gsk3 inhibit | Small molecule | preclinical - no dev since 2005 |

| Diabetes | NOVO Nordisk | wnt pathway | gsk3 inhibit | Small molecule | Preclinical - no dev since 2004 |

| Cancer | UTSW | IWP | Porcupine | Discovery | |

A more favorable approach to the modulation of the Wnt pathway has been to focus on extracellular mediators of the pathway. Where, Amgen is the first in class to develop a biologic therapeutic against Sclerostin (Human Clinical Phase II). Nuvelo is following Amgen with biologics against LRP5, Dkk1, and R-Spondin (Discovery). Second in class for Sclerostin blocking antibodies will be Novartis and Eli Lilly (Preclinical). Fibrogen, who is taking a different approach, has developed a biologic against CCN family member CTGF (Preclinical). As for small molecules, OsteoGeneX is first in class to develop a Sclerostin small molecule inhibitor, currently in preclinical and lead optimization. Alternatively to Sclerostin, Galapagos is developing small molecule leads against LRP5 in a partnership with Eli-Lilly (Discovery).

The Last Word

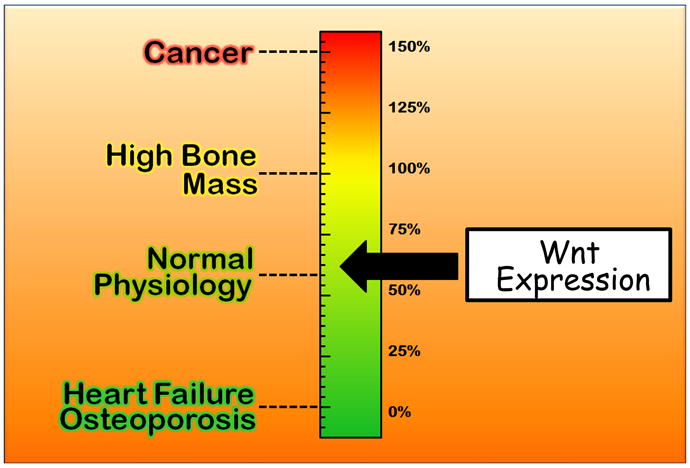

In summary, one important point which must be remembered when thinking of the Wnt signaling pathway – that it is not an off-on situation, and that it is cell specific. Wnt signaling is not binary; it requires fine tuning in order to be properly controlled during normal physiology (Figure 6). Imagine a scale from 0- 150%, where 0% represents no Wnt activity and 150% represents 50% over normal Wnt activity. At 150%, Wnt is more than constitutively activated and this leads to cancer. 100% of Wnt activity leads to high bone mass, and 60% Wnt activity leads to normal bone physiology. Heart failure and osteoporosis would be found at 0% Wnt activity. This modulation is critical and developing therapeutics against the Wnt pathway is tricky. Finding the right target and making sure it acts on the target and nowhere else within the Wnt pathway is vital to making sure the therapeutic will not be triggering off-target sideffects especially in the unwanted scale above.

Figure 6.

Universal schematic of Wnt Thermostat. High reading leads to cancer, whereas a low reading leads to heart failure or osteoporosis depending on the cell type.

Modulation of the Wnt pathway is not binary; one needs fine-tune the signal to receive the desired outcome.

Acknowledgments

The authors are supported by grants to DLE from the Kansas Bioscience Authority, US department of Health and Human Services, the National Institute of Health, and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and skin diseases (NIAMS).

References

- Adaimy L, Chouery E, Megarbane H, Mroueh S, Delague V, Nicolas E, Belguith H, de Mazancourt P, Megarbane A. Mutation in WNT10A is associated with an autosomal recessive ectodermal dysplasia: the odonto-onycho-dermal dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:821–828. doi: 10.1086/520064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrazola MS, Varela-Nallar L, Colombres M, Toledo EM, Cruzat F, Pavez L, Assar R, Aravena A, Gonzalez M, Montecino M, Maass A, Martinez S, Inestrosa NC. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type IV is a target gene of the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2009 doi: 10.1002/jcp.21902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod JD, Miller JR, Shulman JM, Moon RT, Perrimon N. Differential recruitment of Dishevelled provides signaling specificity in the planar cell polarity and Wingless signaling pathways. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2610–2622. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.16.2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baehs S, Herbst A, Thieme SE, Perschl C, Behrens A, Scheel S, Jung A, Brabletz T, Goke B, Blum H, Kolligs FT. Dickkopf-4 is frequently down-regulated and inhibits growth of colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2009;276:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bafico A, Liu G, Yaniv A, Gazit A, Aaronson SA. Novel mechanism of Wnt signalling inhibition mediated by Dickkopf-1 interaction with LRP6/Arrow. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:683–686. doi: 10.1038/35083081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balemans W, Ebeling M, Patel N, Van Hul E, Olson P, Dioszegi M, Lacza C, Wuyts W, Van Den Ende J, Willems P, Paes-Alves AF, Hill S, Bueno M, Ramos FJ, Tacconi P, Dikkers FG, Stratakis C, Lindpaintner K, Vickery B, Foernzler D, Van Hul W. Increased bone density in sclerosteosis is due to the deficiency of a novel secreted protein (SOST) Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:537–543. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.5.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthazart J, Voigt C, Boseret G, Ball GF. Expression of reelin, its receptors and its intracellular signaling protein, Disabled1 in the canary brain: relationships with the song control system. Neuroscience. 2008;153:944–962. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, Ridgway RA, van Es JH, van de Wetering M, Begthel H, van den Born M, Danenberg E, Clarke AR, Sansom OJ, Clevers H. Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of intestinal cancer. Nature. 2009;457:608–611. doi: 10.1038/nature07602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beighton P. Genetic disorders in Southern Africa. S Afr Med J. 1976;50:1125–1128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beighton P, Cremin BJ, Hamersma H. The radiology of sclerosteosis. Br J Radiol. 1976a;49:934–939. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-49-587-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beighton P, Davidson J, Durr L, Hamersma H. Sclerosteosis - an autosomal recessive disorder. Clin Genet. 1977a;11:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1977.tb01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beighton P, Durr L, Hamersma H. The clinical features of sclerosteosis. A review of the manifestations in twenty-five affected individuals. Ann Intern Med. 1976b;84:393–397. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-84-4-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beighton P, Horan F, Hamersma H. A review of the osteopetroses. Postgrad Med J. 1977b;53:507–516. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.53.622.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann C, Senderek J, Anhuf D, Thiel CT, Ekici AB, Poblete-Gutierrez P, van Steensel M, Seelow D, Nurnberg G, Schild HH, Nurnberg P, Reis A, Frank J, Zerres K. Mutations in the gene encoding the Wnt-signaling component R-spondin 4 (RSPO4) cause autosomal recessive anonychia. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:1105–1109. doi: 10.1086/509789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernfield M, Gotte M, Park PW, Reizes O, Fitzgerald ML, Lincecum J, Zako M. Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:729–777. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biason-Lauber A, Konrad D, Navratil F, Schoenle EJ. A WNT4 mutation associated with Mullerian-duct regression and virilization in a 46,XX woman. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:792–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisson I, Prowse DM. WNT signaling regulates self-renewal and differentiation of prostate cancer cells with stem cell characteristics. Cell Res. 2009;19:683–697. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund P, Svedlund J, Olsson AK, Akerstrom G, Westin G. The internally truncated LRP5 receptor presents a therapeutic target in breast cancer. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaydon DC, Ishii Y, O’Toole EA, Unsworth HC, Teh MT, Ruschendorf F, Sinclair C, Hopsu-Havu VK, Tidman N, Moss C, Watson R, de Berker D, Wajid M, Christiano AM, Kelsell DP. The gene encoding R-spondin 4 (RSPO4), a secreted protein implicated in Wnt signaling, is mutated in inherited anonychia. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1245–1247. doi: 10.1038/ng1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyden LM, Mao J, Belsky J, Mitzner L, Farhi A, Mitnick MA, Wu D, Insogna K, Lifton RP. High bone density due to a mutation in LDL-receptor-related protein 5. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1513–1521. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannon M, Gomperts M, Sumoy L, Moon RT, Kimelman D. A beta-catenin/XTcf-3 complex binds to the siamois promoter to regulate dorsal axis specification in Xenopus. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2359–2370. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigstock DR. The connective tissue growth factor/cysteine-rich 61/nephroblastoma overexpressed (CCN) family. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:189–206. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.2.0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunkow ME, Gardner JC, Van Ness J, Paeper BW, Kovacevich BR, Proll S, Skonier JE, Zhao L, Sabo PJ, Fu Y, Alisch RS, Gillett L, Colbert T, Tacconi P, Galas D, Hamersma H, Beighton P, Mulligan J. Bone dysplasia sclerosteosis results from loss of the SOST gene product, a novel cystine knot-containing protein. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:577–589. doi: 10.1086/318811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner E, Peter O, Schweizer L, Basler K. pangolin encodes a Lef-1 homologue that acts downstream of Armadillo to transduce the Wingless signal in Drosophila. Nature. 1997;385:829–833. doi: 10.1038/385829a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carron C, Pascal A, Djiane A, Boucaut JC, Shi DL, Umbhauer M. Frizzled receptor dimerization is sufficient to activate the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2541–2550. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheah PY. Recent advances in colorectal cancer genetics and diagnostics. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2009;69:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulides C, Scarda A, Granzotto M, Milan G, Dalla Nora E, Keogh J, De Pergola G, Stirling H, Pannacciulli N, Sethi JK, Federspil G, Vidal-Puig A, Farooqi IS, O’Rahilly S, Vettor R. WNT10B mutations in human obesity. Diabetologia. 2006;49:678–684. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0144-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung MT, Sytwu HK, Yan MD, Shih YL, Chang CC, Yu MH, Chu TY, Lai HC, Lin YW. Promoter methylation of SFRPs gene family in cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen ED, Ihida-Stansbury K, Lu MM, Panettieri RA, Jones PL, Morrisey EE. Wnt signaling regulates smooth muscle precursor development in the mouse lung via a tenascin C/PDGFR pathway. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2538–2549. doi: 10.1172/JCI38079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs GS, Covey TM, Virshup DM. Wnt signaling in development, disease and translational medicine. Curr Drug Targets. 2008;9:513–531. doi: 10.2174/138945008784911796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dann CE, Hsieh JC, Rattner A, Sharma D, Nathans J, Leahy DJ. Insights into Wnt binding and signalling from the structures of two Frizzled cysteine-rich domains. Nature. 2001;412:86–90. doi: 10.1038/35083601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ferrari GV, Papassotiropoulos A, Biechele T, Wavrant De-Vrieze F, Avila ME, Major MB, Myers A, Saez K, Henriquez JP, Zhao A, Wollmer MA, Nitsch RM, Hock C, Morris CM, Hardy J, Moon RT. Common genetic variation within the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9434–9439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603523104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhoot GK, Gustafsson MK, Ai X, Sun W, Standiford DM, Emerson CP., Jr Regulation of Wnt signaling and embryo patterning by an extracellular sulfatase. Science. 2001;293:1663–1666. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5535.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellies D, Krumlauf R. Wise/sost nucleic acid sequences and amino acid sequences. USA: Stowers Institute For Medical Research; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ellies DL, Viviano B, McCarthy J, Rey JP, Itasaki N, Saunders S, Krumlauf R. Bone density ligand, Sclerostin, directly interacts with LRP5 but not LRP5G171V to modulate Wnt activity. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1738–1749. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr GH, 3rd, Ferkey DM, Yost C, Pierce SB, Weaver C, Kimelman D. Interaction among GSK-3, GBP, axin, and APC in Xenopus axis specification. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:691–702. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman SR, Pizzo SV. Purification and characterization of a “half-molecule” alpha 2-macroglobulin from the southern grass frog: absence of binding to the mammalian alpha 2-macroglobulin receptor. Biochemistry. 1986;25:721–727. doi: 10.1021/bi00351a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florez JC, Jablonski KA, Bayley N, Pollin TI, de Bakker PI, Shuldiner AR, Knowler WC, Nathan DM, Altshuler D. TCF7L2 polymorphisms and progression to diabetes in the Diabetes Prevention Program. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:241–250. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester WC, Kim C, Garriga G. The Caenorhabditis elegans Ror RTK CAM-1 inhibits EGL-20/Wnt signaling in cell migration. Genetics. 2004;168:1951–1962. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.031781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao R, Brigstock DR. Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) is a heparin-dependent adhesion receptor for connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) in rat activated hepatic stellate cells. Hepatol Res. 2003;27:214–220. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6346(03)00241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gliemann J, Moestrup S, Henning Jensen P, Sottrup-Jensen L, Busk Andersen H, Munck Petersen C, Sonne O. Evidence for binding of human pregnancy zone protein-proteinase complex to alpha 2-macroglobulin receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;883:400–406. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(86)90276-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong EL, Stoltfus LJ, Brion CM, Murugesh D, Rubin EM. Contrasting in vivo effects of murine and human apolipoprotein A-II. Role of monomer versus dimer. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5984–5987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.5984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Slee RB, Fukai N, Rawadi G, Roman-Roman S, Reginato AM, Wang H, Cundy T, Glorieux FH, Lev D, Zacharin M, Oexle K, Marcelino J, Suwairi W, Heeger S, Sabatakos G, Apte S, Adkins WN, Allgrove J, Arslan-Kirchner M, Batch JA, Beighton P, Black GC, Boles RG, Boon LM, Borrone C, Brunner HG, Carle GF, Dallapiccola B, De Paepe A, Floege B, Halfhide ML, Hall B, Hennekam RC, Hirose T, Jans A, Juppner H, Kim CA, Keppler-Noreuil K, Kohlschuetter A, LaCombe D, Lambert M, Lemyre E, Letteboer T, Peltonen L, Ramesar RS, Romanengo M, Somer H, Steichen-Gersdorf E, Steinmann B, Sullivan B, Superti-Furga A, Swoboda W, van den Boogaard MJ, Van Hul W, Vikkula M, Votruba M, Zabel B, Garcia T, Baron R, Olsen BR, Warman ML. LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) affects bone accrual and eye development. Cell. 2001;107:513–523. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00571-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant SF, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I, Benediktsson R, Manolescu A, Sainz J, Helgason A, Stefansson H, Emilsson V, Helgadottir A, Styrkarsdottir U, Magnusson KP, Walters GB, Palsdottir E, Jonsdottir T, Gudmundsdottir T, Gylfason A, Saemundsdottir J, Wilensky RL, Reilly MP, Rader DJ, Bagger Y, Christiansen C, Gudnason V, Sigurdsson G, Thorsteinsdottir U, Gulcher JR, Kong A, Stefansson K. Variant of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene confers risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2006;38:320–323. doi: 10.1038/ng1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzeschik KH, Bornholdt D, Oeffner F, Konig A, del Carmen Boente M, Enders H, Fritz B, Hertl M, Grasshoff U, Hofling K, Oji V, Paradisi M, Schuchardt C, Szalai Z, Tadini G, Traupe H, Happle R. Deficiency of PORCN, a regulator of Wnt signaling, is associated with focal dermal hypoplasia. Nat Genet. 2007;39:833–835. doi: 10.1038/ng2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habas R, Dawid IB. Dishevelled and Wnt signaling: is the nucleus the final frontier? J Biol. 2005;4:2. doi: 10.1186/jbiol22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z. Recent progress in genomic [corrected] research of liver cancer. Sci China C Life Sci. 2009;52:24–30. doi: 10.1007/s11427-009-0010-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen ST, Jr, Taylor TK, Honet JC, Lewis FR. Fracture-dislocations of the ankylosed thoracic spine in rheumatoid spondylitis. Ankylosing spondylitis, Marie-Strumpell disease. J Trauma. 1967;7:827–837. doi: 10.1097/00005373-196711000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick TM, Cooper JA. High affinity binding of Dab1 to Reelin receptors promotes normal positioning of upper layer cortical plate neurons. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;126:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata H, Hinoda Y, Nakajima K, Kikuno N, Yamamura S, Kawakami K, Suehiro Y, Tabatabai ZL, Ishii N, Dahiya R. Wnt antagonist gene polymorphisms and renal cancer. Cancer. 2009;115:4488–4503. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeppner LH, Secreto FJ, Westendorf JJ. Wnt signaling as a therapeutic target for bone diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13:485–496. doi: 10.1517/14728220902841961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu DR, Economides AN, Wang X, Eimon PM, Harland RM. The Xenopus dorsalizing factor Gremlin identifies a novel family of secreted proteins that antagonize BMP activities. Mol Cell. 1998;1:673–683. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H. Cell-surface heparan sulfate is involved in the repulsive guidance activities of Slit2 protein. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:695–701. doi: 10.1038/89482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsken J, Behrens J. The Wnt signalling pathway. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3977–3978. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Oz HS, Wiland D, Gharib S, Deshpande R, Hill RJ, Katz WS, Sternberg PW. C. elegans LIN-18 is a Ryk ortholog and functions in parallel to LIN-17/Frizzled in Wnt signaling. Cell. 2004;118:795–806. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itasaki N, Jones CM, Mercurio S, Rowe A, Domingos PM, Smith JC, Krumlauf R. Wise, a context-dependent activator and inhibitor of Wnt signalling. Development. 2003;130:4295–4305. doi: 10.1242/dev.00674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins ZA, van Kogelenberg M, Morgan T, Jeffs A, Fukuzawa R, Pearl E, Thaller C, Hing AV, Porteous ME, Garcia-Minaur S, Bohring A, Lacombe D, Stewart F, Fiskerstrand T, Bindoff L, Berland S, Ades LC, Tchan M, David A, Wilson LC, Hennekam RC, Donnai D, Mansour S, Cormier-Daire V, Robertson SP. Germline mutations in WTX cause a sclerosing skeletal dysplasia but do not predispose to tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 2009;41:95–100. doi: 10.1038/ng.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Zou L, Zhang C, He S, Cheng C, Xu J, Lu W, Zhang Y, Zhang H, Wang D, Shen A. PPARgamma and Wnt/beta-Catenin pathway in human breast cancer: expression pattern, molecular interaction and clinical/prognostic correlations. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:1551–1559. doi: 10.1007/s00432-009-0602-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ML, Rajamannan N. Diseases of Wnt signaling. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2006;7:41–49. doi: 10.1007/s11154-006-9003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya N, Ye L, Kobayashi T, Mochida Y, Yamauchi M, Kronenberg HM, Feng JQ, Mishina Y. BMP signaling negatively regulates bone mass through sclerostin by inhibiting the canonical Wnt pathway. Development. 2008;135:3801–3811. doi: 10.1242/dev.025825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa A, Tsukada S, Sekine A, Tsunoda T, Takahashi A, Kashiwagi A, Tanaka Y, Babazono T, Matsuda M, Kaku K, Iwamoto Y, Kawamori R, Kikkawa R, Nakamura Y, Maeda S. Association of the gene encoding wingless-type mammary tumor virus integration-site family member 5B (WNT5B) with type 2 diabetes. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:832–843. doi: 10.1086/425340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansara M, Tsang M, Kodjabachian L, Sims NA, Trivett MK, Ehrich M, Dobrovic A, Slavin J, Choong PF, Simmons PJ, Dawid IB, Thomas DM. Wnt inhibitory factor 1 is epigenetically silenced in human osteosarcoma, and targeted disruption accelerates osteosarcomagenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:837–851. doi: 10.1172/JCI37175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibar Z, Capra V, Gros P. Toward understanding the genetic basis of neural tube defects. Clin Genet. 2007;71:295–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KA, Wagle M, Tran K, Zhan X, Dixon MA, Liu S, Gros D, Korver W, Yonkovich S, Tomasevic N, Binnerts M, Abo A. R-Spondin family members regulate the Wnt pathway by a common mechanism. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:2588–2596. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-02-0187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler KW, Nilbert MC, Vogelstein B, Bryan TM, Levy DB, Smith KJ, Preisinger AC, Hamilton SR, Hedge P, Markham A, et al. Identification of a gene located at chromosome 5q21 that is mutated in colorectal cancers. Science. 1991;251:1366–1370. doi: 10.1126/science.1848370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn AD, Moon RT. Wnt and calcium signaling: beta-catenin-independent pathways. Cell Calcium. 2005;38:439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusu N, Laurikkala J, Imanishi M, Usui H, Konishi M, Miyake A, Thesleff I, Itoh N. Sclerostin is a novel secreted osteoclast-derived bone morphogenetic protein antagonist with unique ligand specificity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24113–24117. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301716200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagathu C, Christodoulides C, Virtue S, Cawthorn WP, Franzin C, Kimber WA, Nora ED, Campbell M, Medina-Gomez G, Cheyette BN, Vidal-Puig AJ, Sethi JK. Dact1, a nutritionally regulated preadipocyte gene, controls adipogenesis by coordinating the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling network. Diabetes. 2009;58:609–619. doi: 10.2337/db08-1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammi L, Arte S, Somer M, Jarvinen H, Lahermo P, Thesleff I, Pirinen S, Nieminen P. Mutations in AXIN2 cause familial tooth agenesis and predispose to colorectal cancer. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:1043–1050. doi: 10.1086/386293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenting PJ, Neels JG, van den Berg BM, Clijsters PP, Meijerman DW, Pannekoek H, van Mourik JA, Mertens K, van Zonneveld AJ. The light chain of factor VIII comprises a binding site for low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23734–23739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.23734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Buff EM, Perrimon N, Michelson AM. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans are essential for FGF receptor signaling during Drosophila embryonic development. Development. 1999;126:3715–3723. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RD, Carulli JP, Del Mastro RG, Dupuis J, Osborne M, Folz C, Manning SP, Swain PM, Zhao SC, Eustace B, Lappe MM, Spitzer L, Zweier S, Braunschweiger K, Benchekroun Y, Hu X, Adair R, Chee L, FitzGerald MG, Tulig C, Caruso A, Tzellas N, Bawa A, Franklin B, McGuire S, Nogues X, Gong G, Allen KM, Anisowicz A, Morales AJ, Lomedico PT, Recker SM, Van Eerdewegh P, Recker RR, Johnson ML. A mutation in the LDL receptor-related protein 5 gene results in the autosomal dominant high-bone-mass trait. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:11–19. doi: 10.1086/338450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Bafico A, Harris VK, Aaronson SA. A novel mechanism for Wnt activation of canonical signaling through the LRP6 receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5825–5835. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5825-5835.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loots GG, Kneissel M, Keller H, Baptist M, Chang J, Collette NM, Ovcharenko D, Plajzer-Frick I, Rubin EM. Genomic deletion of a long-range bone enhancer misregulates sclerostin in Van Buchem disease. Genome Res. 2005;15:928–935. doi: 10.1101/gr.3437105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Tinsley HN, Keeton A, Qu Z, Piazza GA, Li Y. Suppression of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling inhibits prostate cancer cell proliferation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;602:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Yamamoto V, Ortega B, Baltimore D. Mammalian Ryk is a Wnt coreceptor required for stimulation of neurite outgrowth. Cell. 2004;119:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major MB, Camp ND, Berndt JD, Yi X, Goldenberg SJ, Hubbert C, Biechele TL, Gingras AC, Zheng N, Maccoss MJ, Angers S, Moon RT. Wilms tumor suppressor WTX negatively regulates WNT/beta-catenin signaling. Science. 2007;316:1043–1046. doi: 10.1126/science/1141515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel H, Shemer R, Borochowitz ZU, Okopnik M, Knopf C, Indelman M, Drugan A, Tiosano D, Gershoni-Baruch R, Choder M, Sprecher E. SERKAL syndrome: an autosomal-recessive disorder caused by a loss-of-function mutation in WNT4. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani A, Radhakrishnan J, Wang H, Mani MA, Nelson-Williams C, Carew KS, Mane S, Najmabadi H, Wu D, Lifton RP. LRP6 mutation in a family with early coronary disease and metabolic risk factors. Science. 2007;315:1278–1282. doi: 10.1126/science.1136370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May P, Herz J, Bock HH. Molecular mechanisms of lipoprotein receptor signalling. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:2325–2338. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5231-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercurio S, Latinkic B, Itasaki N, Krumlauf R, Smith JC. Connective-tissue growth factor modulates WNT signalling and interacts with the WNT receptor complex. Development. 2004;131:2137–2147. doi: 10.1242/dev.01045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monga SP. Role of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in liver metabolism and cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam JS, Turcotte TJ, Smith PF, Choi S, Yoon JK. Mouse cristin/R-spondin family proteins are novel ligands for the Frizzled 8 and LRP6 receptors and activate beta-catenin-dependent gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13247–13257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemann S, Zhao C, Pascu F, Stahl U, Aulepp U, Niswander L, Weber JL, Muller U. Homozygous WNT3 mutation causes tetra-amelia in a large consanguineous family. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:558–563. doi: 10.1086/382196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishisho I, Nakamura Y, Miyoshi Y, Miki Y, Ando H, Horii A, Koyama K, Utsunomiya J, Baba S, Hedge P. Mutations of chromosome 5q21 genes in FAP and colorectal cancer patients. Science. 1991;253:665–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1651563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusse R, Varmus HE. Many tumors induced by the mouse mammary tumor virus contain a provirus integrated in the same region of the host genome. Cell. 1982;31:99–109. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90409-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusslein-Volhard C, Wieschaus E. Mutations affecting segment number and polarity in Drosophila. Nature. 1980;287:795–801. doi: 10.1038/287795a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nybakken K, Perrimon N. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan modulation of developmental signaling in Drosophila. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1573:280–291. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00395-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rahilly S, Wareham NJ. Genetic variants and common diseases--better late than never. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:306–308. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe068140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates NA, van Vliet J, Duffy DL, Kroes HY, Martin NG, Boomsma DI, Campbell M, Coulthard MG, Whitelaw E, Chong S. Increased DNA methylation at the AXIN1 gene in a monozygotic twin from a pair discordant for a caudal duplication anomaly. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:155–162. doi: 10.1086/505031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal B. The CCN family of cell growth regulators: a new family of normal and pathologic cell growth and differentiation regulators: lessons from the first international workshop on CCN gene family. Bull Cancer. 2001;88:645–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad A, Paruchuri V, Preet A, Latif F, Ganju RK. Slit-2 induces a tumor-suppressive effect by regulating beta-catenin in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:26624–26633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800679200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin M, Hayashi H, Oshima K, Tahira T, Hayashi K, Kondo H. Complexity of the genotype-phenotype correlation in familial exudative vitreoretinopathy with mutations in the LRP5 and/or FZD4 genes. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:104–112. doi: 10.1002/humu.20191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn KA, Grimsley PG, Dai YP, Tapner M, Chesterman CN, Owensby DA. Soluble low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) circulates in human plasma. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23946–23951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichsman F, Smith L, Cumberledge S. Glycosaminoglycans can modulate extracellular localization of the wingless protein and promote signal transduction. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:819–827. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.3.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera MN, Kim WJ, Wells J, Driscoll DR, Brannigan BW, Han M, Kim JC, Feinberg AP, Gerald WL, Vargas SO, Chin L, Iafrate AJ, Bell DW, Haber DA. An X chromosome gene, WTX, is commonly inactivated in Wilms tumor. Science. 2007;315:642–645. doi: 10.1126/science.1137509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robitaille J, MacDonald ML, Kaykas A, Sheldahl LC, Zeisler J, Dube MP, Zhang LH, Singaraja RR, Guernsey DL, Zheng B, Siebert LF, Hoskin-Mott A, Trese MT, Pimstone SN, Shastry BS, Moon RT, Hayden MR, Goldberg YP, Samuels ME. Mutant frizzled-4 disrupts retinal angiogenesis in familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Nat Genet. 2002;32:326–330. doi: 10.1038/ng957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann H, Holtz J, Zerkowski HR, Hatzfeld M. Expression of secreted frizzled related proteins 3 and 4 in human ventricular myocardium correlates with apoptosis related gene expression. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;45:720–728. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00376-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segarini PR, Nesbitt JE, Li D, Hays LG, Yates JR, 3rd, Carmichael DF. The low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein/alpha2-macroglobulin receptor is a receptor for connective tissue growth factor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40659–40667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selva EM, Perrimon N. Role of heparan sulfate proteoglycans in cell signaling and cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2001;83:67–80. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(01)83003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiegler AL, Burden SJ, Hubbard SR. Crystal Structure of the Frizzled-Like Cysteine-Rich Domain of the Receptor Tyrosine Kinase MuSK. J Mol Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan K, Duquette M, Liu JH, Lawler J, Wang JH. The crystal structure of the heparin-binding reelin-N domain of f-spondin. J Mol Biol. 2008;381:1213–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theisen H, Purcell J, Bennett M, Kansagara D, Syed A, Marsh JL. dishevelled is required during wingless signaling to establish both cell polarity and cell identity. Development. 1994;120:347–360. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomes C, Downey LM, Bottomley HM, Scott S, Woodruff G, Trembath RC, Inglehearn CF. Identification of a fourth locus (EVR4) for familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR) Mol Vis. 2004;10:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoda H, Kinoshita-Toyoda A, Fox B, Selleck SB. Structural analysis of glycosaminoglycans in animals bearing mutations in sugarless, sulfateless, and tout-velu. Drosophila homologues of vertebrate genes encoding glycosaminoglycan biosynthetic enzymes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21856–21861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugur SA, Tolun A. Homozygous WNT10b mutation and complex inheritance in Split-Hand/Foot Malformation. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2644–2653. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Driel IR, Davis CG, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Self-association of the low density lipoprotein receptor mediated by the cytoplasmic domain. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:16127–16134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meurs JB, Trikalinos TA, Ralston SH, Balcells S, Brandi ML, Brixen K, Kiel DP, Langdahl BL, Lips P, Ljunggren O, Lorenc R, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Ohlsson C, Pettersson U, Reid DM, Rousseau F, Scollen S, Van Hul W, Agueda L, Akesson K, Benevolenskaya LI, Ferrari SL, Hallmans G, Hofman A, Husted LB, Kruk M, Kaptoge S, Karasik D, Karlsson MK, Lorentzon M, Masi L, McGuigan FE, Mellstrom D, Mosekilde L, Nogues X, Pols HA, Reeve J, Renner W, Rivadeneira F, van Schoor NM, Weber K, Ioannidis JP, Uitterlinden AG. Large-scale analysis of association between LRP5 and LRP6 variants and osteoporosis. JAMA. 2008;299:1277–1290. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.11.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Reid Sutton V, Omar Peraza-Llanes J, Yu Z, Rosetta R, Kou YC, Eble TN, Patel A, Thaller C, Fang P, Van den Veyver IB. Mutations in X-linked PORCN, a putative regulator of Wnt signaling, cause focal dermal hypoplasia. Nat Genet. 2007;39:836–838. doi: 10.1038/ng2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Hanifi-Moghaddam P, Hanekamp EE, Kloosterboer HJ, Franken P, Veldscholte J, van Doorn HC, Ewing PC, Kim JJ, Grootegoed JA, Burger CW, Fodde R, Blok LJ. Progesterone inhibition of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in normal endometrium and endometrial cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5784–5793. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisgraber KH, Shinto LH. Identification of the disulfide-linked homodimer of apolipoprotein E3 in plasma. Impact on receptor binding activity. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:12029–12034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler DG, Sutherland MS, Ojala E, Turcott E, Geoghegan JC, Shpektor D, Skonier JE, Yu C, Latham JA. Sclerostin inhibition of Wnt-3a-induced C3H10T1/2 cell differentiation is indirect and mediated by bone morphogenetic proteins. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2498–2502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400524200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods CG, Stricker S, Seemann P, Stern R, Cox J, Sherridan E, Roberts E, Springell K, Scott S, Karbani G, Sharif SM, Toomes C, Bond J, Kumar D, Al-Gazali L, Mundlos S. Mutations in WNT7A cause a range of limb malformations, including Fuhrmann syndrome and Al-Awadi/Raas-Rothschild/Schinzel phocomelia syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:402–408. doi: 10.1086/506332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Wang Y, Dabdoub A, Smallwood PM, Williams J, Woods C, Kelley MW, Jiang L, Tasman W, Zhang K, Nathans J. Vascular development in the retina and inner ear: control by Norrin and Frizzled-4, a high-affinity ligand-receptor pair. Cell. 2004;116:883–895. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00216-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H, Kitadai Y, Oue N, Ohdan H, Yasui W, Kikuchi A. Laminin gamma2 mediates Wnt5a-induced invasion of gastric cancer cells. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:242–252. 252 e241–246. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang TM, Leu SW, Li JM, Hung MS, Lin CH, Lin YC, Huang TJ, Tsai YH, Yang CT. WIF-1 promoter region hypermethylation as an adjuvant diagnostic marker for non-small cell lung cancer-related malignant pleural effusions. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:919–924. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0527-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberberg A, Yaniv A, Gazit A. The low density lipoprotein receptor-1, LRP1, interacts with the human frizzled-1 (HFz1) and down-regulates the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004a;279:17535–17542. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311292200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberberg A, Yaniv A, Gazit A. The low density lipoprotein receptor-1, LRP1, interacts with the human frizzled-1 (HFz1) and down-regulates the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004b;279:17535–17542. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311292200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]