Abstract

Light-oxygen-voltage (LOV) domains are blue light-activated signaling modules integral to a wide range of photosensory proteins. Upon illumination, LOV domains form internal protein-flavin adducts that generate conformational changes which control effector function. Here we advance our understanding of LOV regulation with structural, biophysical, and biochemical studies of EL222, a light-regulated DNA-binding protein. The dark-state crystal structure reveals interactions between the EL222 LOV and helix-turn-helix domains that we show inhibit DNA binding. Solution biophysical data indicate that illumination breaks these interactions, freeing the LOV and helix-turn-helix domains of each other. This conformational change has a key functional effect, allowing EL222 to bind DNA in a light-dependent manner. Our data reveal a conserved signaling mechanism among diverse LOV-containing proteins, where light-induced conformational changes trigger activation via a conserved interaction surface.

Keywords: allosteric regulation, photosensing, PER-ARNT-SIM domain

Environmental sensory proteins play a crucial function for cellular adaptation in response to changing conditions. These proteins frequently contain effector domains whose activity is regulated by specialized sensory domains sensitive to various stimuli. One widely distributed class of such sensory domains is the PAS (PER-ARNT-SIM) family, whose members typically regulate protein/protein interactions in response to changing environmental cues (1). A subset of PAS domains, called light-oxygen-voltage (LOV) domains, use flavin cofactors to detect changes in blue light intensity or redox state (2). LOV domains are found in regulatory proteins for phototropism (3), seasonal gene transcription (4), bacterial stress responses (5, 6), and many other diverse biological responses. Within these pathways, LOV domains control a wide range of effector domains, including kinases, F boxes, and DNA-binding domains (7). Recently, these natural proteins have been joined by engineered LOV fusions that confer in vitro and in vivo LOV-based photoregulation to a range of protein targets (8–11).

This raises the question: How can a class of light-regulated domains with similar tertiary structures control such a wide variety of effectors? What is clear is that LOV domains all share similar architectures and photochemical responses to illumination, harnessing the energy of incoming blue light photons to form a covalent adduct between the Sγ sulfur on a conserved cysteine residue and the C4a carbon of a flavin cofactor (12, 13). Formation of this bond generates structural changes that propagate to the domain surface, altering the interactions of the core LOV domain with intra- or interprotein partners (14–18). For example, structural studies on Avena sativa phototropin 1 LOV2 (AsLOV2) demonstrated light-induced unfolding of the Jα-helix located C-terminal to the canonical LOV domain (15). Similarly, the Neurospora crassa VIVID protein reorients an N-terminal α-helix, β-strand extension of its LOV domain upon illumination (18). In both cases, the external structures interact with the β-sheet surface of the LOV domain, suggesting a site for signal propagation common between them. The functional importance of regulated interactions at this site have been validated by the ability of point mutations on the β-sheet or interacting effector surfaces to decouple changes in effector activity from adduct formation (18, 19).

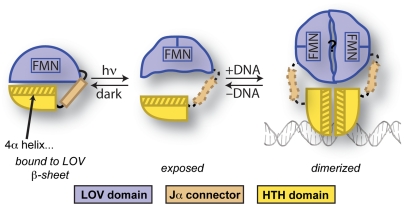

Among the known LOV-containing proteins are several transcription factors, such as the zinc-finger containing N. crassa white collar-1 (WC-1) (20) and the algal basic leucine zipper AUREOCHROMEs (21). Although light controls the binding of these proteins to DNA, the mechanism(s) of this regulation is not understood at a molecular level. Here we address this shortcoming by examining how a LOV domain directly regulates DNA binding, establishing the generality of LOV signaling. Our studies focus on EL222, a 222 amino acid protein isolated from the marine bacterium Erythrobacter litoralis HTCC2594. In addition to an N-terminal LOV domain, EL222 also contains a C-terminal helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA-binding domain representative of LuxR-type DNA-binding proteins (22). Combining regulatory models from a diverse group of LOV-based photosensors (15) and LuxR-type proteins (23), we hypothesized that the EL222 N-terminal LOV domain represses DNA-binding activity of the C-terminal domain in the dark, and that this inhibition would be released with blue light illumination.

Results

Dark-State Crystal Structure of EL222 Suggests Mode to Inhibit DNA Binding.

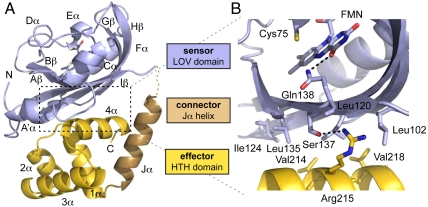

As an initial step to examining this model, we solved the 2.1-Å resolution crystal structure of EL222 in the dark state (Table S1), observing interactions between the LOV and HTH domains consistent with our hypothesis (Fig. 1). The EL222 structure contains both of the two expected domains, an N-terminal α/β LOV domain and a C-terminal all-helical HTH domain. A single FMN chromophore was observed within the LOV domain, orienting the critical isoalloxazine C4a atom only 3.9 Å from the cysteine (Cys) 75 Sγ atom that is expected to form the photochemical adduct. The LOV domain is followed by a C-terminal Jα-helix as observed in other LOV structures (15, 24), but here serves as an interdomain linker that associates more closely with the HTH effector domain rather than docking onto the LOV β-sheet surface as in AsLOV2 (15). This arrangement allows the EL222 LOV β-sheet surface to directly interact with the 4α-helix and 1α-2α loop of the HTH domain. This β-sheet interface is analogous to that used by other LOV and PAS domains to bind their effectors (25) (Fig. S1), burying approximately 700 Å2 of surface area between the EL222 LOV and HTH domains. Notably, we observed differences in the relative arrangement of the LOV and HTH domains in the two molecules of EL222 found in the asymmetric unit, due to the translation of the HTH domain by approximately 2.5 Å parallel to the axis of helix 4α (Fig. S1E). Although this translation slightly alters the particular interactions between domains (Table S2), both molecules still fundamentally use a similar mix of hydrophobic and polar contacts at the LOV/HTH interface (Fig. 1B). The plasticity of this interface is consistent with a signaling role, poised for the facile conversion between conformations via allosteric change within the LOV domain (26). As in the structures of NarL and DosR (27, 28), the regulatory LOV domain of EL222 contacts the HTH dimerization helix (4α), but it does not also directly contact with the DNA-binding recognition helix (3α) as observed with the regulatory domains of these other structures. Such structural comparisons supported our hypothesis that EL222 fails to bind DNA in the dark by both sequestering the likely dimerization interfaces (LOV β-sheet; HTH 4α-helix) and the LOV domain interfering with HTH-DNA interactions (Fig. S2).

Fig. 1.

The dark-state crystal structure of EL222 reveals extensive LOV-HTH interactions predicted to inhibit HTH DNA-binding activity. (A) Overview of EL222 structure, highlighting locations of the LOV (blue) and HTH (gold) domains and the Jα-helix (bronze) connecting the two. The LOV domain binds to the HTH domain using the LOV β-sheet surface, consistent with other LOV-effector complexes. (B) Expansion of the LOV/HTH interface as observed in chain A of the EL222 structure, as indicated by the boxed region in A. To bind the LOV domain, the HTH domain presents the 1α-2α linker and 4α-helix, the latter of which typically provides a dimerization interface for DNA-bound HTH domains. Thus sequestered, the 4α-helix is unable to participate in HTH/HTH interactions observed in many DNA-bound HTH complexes.

Photoactivation of EL222 Leads to Adduct Formation and Domain-Scale Rearrangements.

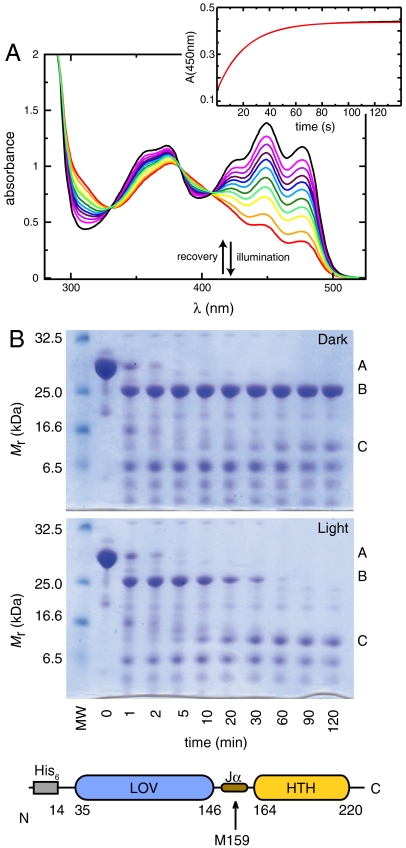

Turning from structure to function, we examined light-induced changes in the visible absorbance spectrum to establish that EL222 can undergo LOV photochemistry. As expected for a flavin-containing LOV domain, we observed significant absorbance around 450 nm with vibrational fine structure (29) (Fig. 2A). This absorbance diminished significantly after illuminating samples, with three isosbestic points at 330, 384, and 407 nm, consistent with formation of the Cys-FMN adduct. After ceasing illumination, we observed subsequent dark-state recovery of the characteristic absorbance profile with first order exponential kinetics (τ = 25.5 s for 25 °C, pH 6.0).

Fig. 2.

Photochemical formation of Cys-FMN adduct in EL222 is correlated with domain-level reorganization. (A) UV-visible absorbance spectra of EL222, showing the expected absorbance near 450 nm with fine structure from protein-FMN interactions for dark-state EL222 (black). Illumination induces covalent adduct formation with a loss of absorbance above 400 nm (red), which gradually returns in the dark with spontaneous adduct decay (orange through purple, spectra recorded approximately every 5 s). The rate of dark-state recovery was determined by fitting the absorbance at 450 nm following illumination. (Inset) Data shown in black and fit to first-order exponential in red. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of chymotrypsin limited proteolysis experiments shows kinetics of degradation are affected by illumination, with the Jα-helical linker becoming more accessible upon illumination. Significantly populated species include His6-EL222 (14–222) (A), EL222 (14–222) (B), and EL222 (14–156, corresponding to an isolated LOV domain) (C).

Having established the photosensitivity of EL222, we probed the ability of adduct formation to generate large-scale conformational changes using limited proteolysis. Both dark and lit EL222 treated with chymotrypsin demonstrated an initial cleavage removing the N-terminal His6-tag within the first 5 min (Fig. 2B), but exhibited different behavior with extended incubation times. Dark-state samples underwent little additional proteolysis, consistent with a well-folded, compact protein. In contrast, lit-state samples were more quickly and extensively proteolyzed, with little full-length protein remaining intact after 60 min. Notably, chymotrypsin treatment of lit-state samples generated stable fragments, one of which was consistent with an intact LOV domain (Fig. 2B, species C). Mass spectrometry established that this fragment was generated by cleavage within the interdomain Jα-helical linker at Met159, which packs against the HTH 4α-helix in the dark-state structure. These data, together with our observation of protease-resistant fragments in dark conditions, suggest that light-induced conformational changes increase the accessibility of the Jα-linker via reorientation of the ordered LOV and HTH domains. This is supported by limited differences between CD spectra recorded under dark and lit conditions (Fig. S3).

NMR Studies of EL222 Photoactivation Establish Long-Range Light-Induced Conformational Changes.

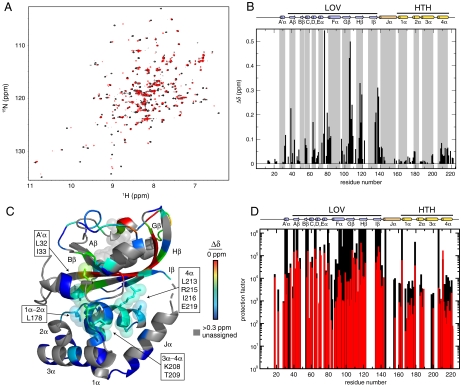

To probe these light-induced changes at higher resolution, we used solution NMR spectroscopy. Using a combination of triple resonance and NOESY data, we assigned 15N, 13C, and 1H chemical shifts of EL222 in the dark state (81% of the backbone, 40% of the side chain). TALOS analyses of these chemical shifts (30), combined with through-space 1H-1H NOE data, let us confirm that EL222 has very similar secondary and tertiary structures in the crystal and solution states. Notably, solution measurements confirmed that EL222 is monomeric under these conditions. Upon illumination, we observed chemical shift and peak intensity changes at many backbone and side chain positions as observed in 15N/1H heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) (Fig. 3A) and 13C/1H HSQC spectra (Fig. S4). Such changes reflect alterations in the local electronic environments around NMR-active nuclei. Critically, all spectra maintained comparable chemical shift dispersion in the dark and lit states, consistent with LOV photochemistry inducing a domain reorientation, but not unfolding as observed in AsLOV2 (15).

Fig. 3.

Solution NMR data suggests EL222 undergoes light-induced rearrangement of two ordered domains. (A) Superposition of 15N/1H HSQC spectra of EL222 acquired under dark (black) or lit (red) conditions show light-induced changes in peak location and intensity. (B) Chemical shift difference analysis of 15N/1H HSQC spectra shown in Fig. 3A indicate significant changes occurring in both domains, including the HTH 1α-2α loop, 3α-4α loop, and 4α-helix located at the interface with the LOV domain. Secondary structure elements as indicated by the NMR data and X-ray structure are indicated. (C) Mapping values from Fig. 3B onto the dark-state crystal structure illustrates the pattern of chemical shift perturbations at the interdomain interface. Side chains are indicated for 1α-2α loop, 3α-4α loop, and 4α-helix residues in the HTH domain with 15N/1H chemical shift changes upon illumination. (D) 2H exchange protection factor analyses (32) of EL222 conducted in the dark (black) and lit (red) states show similar protection, but to a lower overall degree upon illumination, consistent with reorganization of two ordered domains. Protection factors > 106 are lower bound estimates because these sites did not sufficiently exchange for robust fitting of the time-dependent peak intensity changes.

To identify which sites experienced significant changes, we compared 15N/1H HSQC spectra recorded under dark and lit conditions (Fig. 3a), using 15N/1H Scotch exchange spectroscopy to assign lit-state chemical shifts by correlating dark-state 15N shifts with lit-state 1H shifts (31). From the 109 pairs of dark- and lit-state chemical shifts unambiguously assigned with this analysis, we established that chemical shift changes occur throughout the length of the protein (Fig. 3B). Although clusters of perturbed residues in the LOV domain likely report on adduct-induced configurational changes in the FMN chromophore and resulting conformational changes in the surrounding protein, we also clearly observed long-range (> 15 Å from the flavin C4a atom) effects at sites outside the LOV domain as well. These include changes in the N-terminal A’α helix that precedes the LOV domain, plus multiple residues in the HTH domain that are significantly shifted (Δδ > 0.05 ppm; Fig. 3C). These include several residues in the 4α-helix, including Leu213, Arg215, Ile216, and Glu219, plus sites in the 1α-2α (Leu178) and 3α-4α (Lys208, Thr209) loops. All of these residues are proximal to the LOV β-sheet, supporting our limited proteolysis findings that localized light-driven cysteinyl adduct formation triggers structural alterations beyond the LOV domain itself and fully throughout EL222. In addition, the significant perturbation of residues at the interface between the domains further supports an interdomain reorientation upon blue light illumination.

To complement this view from chemical shift changes, we used NMR-based measurements of backbone amide deuterium exchange rates to establish light-induced changes in domain structure and stability. We obtained these data by resuspending uniformly 15N-labeled samples in D2O-containing buffer, monitoring exchange by loss of intensity in consecutively recorded 15N/1H HSQC spectra. As we have not assigned the lit-state chemical shifts, 2H exchange measurements under illumination relied on duty-cycling the sample between the dark and lit states, using assigned dark-state spectra to measure rates. Converting these exchange rate data into protection factors (32), we found that numerous sites across the protein exchanged very slowly in the dark state, consistent with stable hydrogen bonding as expected from regular secondary structure (Fig. 3D). Many amides within the LOV domain β-sheet surface are very well protected as expected for PAS domains (15, 33) and specific residues within the first and fourth helices of the HTH (1α and 4α) appear refractory to exchange. Upon illumination, these highly protected regions showed an overall decrease in protection factor, suggestive of distortion in the LOV structure as previously observed in AsLOV2 (15). The fact that these sites remained protected from exchange overall is consistent with both the LOV and HTH domains remaining stably folded, and with light inducing a separation or relative reorientation of the LOV and HTH domains as suggested by limited proteolysis and chemical shift analyses.

Photoactivation of EL222 Promotes DNA-Binding Activity.

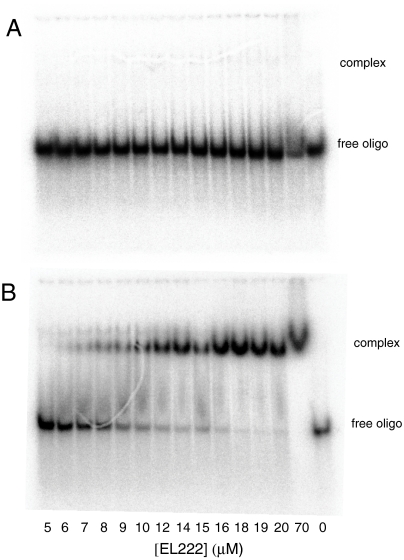

These light-induced structural changes imply a corresponding functional change, which we presumed to be a light-activated DNA-binding activity, given our data above and the domain architecture of EL222. Without a preestablished biological role of this protein, we started without any validated DNA-binding site. To address this issue, we used a candidate-based approach, assuming that EL222 might be autoregulatory and bind to a DNA sequence upstream of its own coding sequence. Scanning through the 350-bp region located 5′ to the start of EL222 translation with a series of 21 overlapping 45-bp candidate sequences tested, none bound EL222 as assessed by gel shift assays conducted under dark conditions. However, all of the candidate sequences bound EL222 under illumination at or above 70-μM protein (Fig. S5A), suggesting light-dependent activation of nonspecific DNA binding. Titrating to lower protein concentrations, we found two sequences that bound EL222 at concentrations as low as 7 μM (Fig. 4 for results of one of these sequences, oligomer 1). In both instances, DNA binding only occurred when the protein:DNA mix was incubated under white light. Binding was cooperative with respect to protein concentration, with a Hill coefficient of approximately four, suggesting that a pair of dimers bound within this 45-bp section. No binding occurred under dark-state conditions, even at protein concentrations capable of nonspecific DNA binding in the light. Protein previously exposed to bright light, then allowed to recover to dark state overnight at 4 °C also demonstrated the same minimal residual DNA-binding activity as protein that was not exposed to light, indicating the activity is reversible and light dependent (Fig. S5B). From these data, we can conclude that EL222 demonstrates light-dependent DNA-binding activity. Although the DNA sequence used in these gel shift experiments bound with the highest affinity of all sequences tested, we suspect that this is not an optimal binding sequence for EL222 based on the affinities of similar HTH-containing proteins for their cognate DNA sequences (34, 35). Nevertheless, these data suggest that this DNA sequence retains its utility for assaying protein activity in future structural and/or functional experiments.

Fig. 4.

EL222 is a light-activated DNA-binding protein. (A) EL222 demonstrates no observable DNA binding to the 45-bp dsDNA oligomer 1 under dark-state conditions at protein concentrations up to 70 μM. (B) Following illumination, cooperative DNA binding is observed to the same 45-bp dsDNA oligomer used for dark-state conditions.

Taken together, our data demonstrate that conformational changes propagate through the LOV domain upon illumination, disrupting inhibitory LOV-HTH interactions mediated by the LOV β-sheet. To test this, we mutated several sites to constitutively break the LOV/HTH dark-state interaction and generate proteins locked in the DNA-binding conformation. One of these mutations, L120K, targeted a hydrophobic patch between the β-sheet surface of the LOV domain and the HTH 4α-helix (Fig. S6A). Gel filtration chromatography established that this mutant is a monomer in solution, as is wild-type EL222 (Fig. S6B). Gel shift assays conducted under dark-state conditions demonstrated that EL222 L120K bound DNA with similar affinity to wild type under lit-state conditions (Fig. S6C). Limited proteolysis of L120K using chymotrypsin showed little difference between the protein in the dark or lit state (Fig. S6D), with both resembling the lit state of wild-type protein. These results suggest that the L120K mutation forces EL222 into a lit-state-like structure that constitutively binds DNA.

Discussion

Within the context of regulation of HTH-containing proteins, our data are consistent with the EL222 LOV domain inhibiting DNA binding in the dark state via interactions with the HTH 4α-helix and several interhelical loops (Figs. 1, 3, and 5). Disruption of these interdomain contacts by light-induced conformational changes in the LOV domain (or mutagenesis of residues at the LOV/HTH interface) induces DNA-binding activity. A similar regulatory model is used by other two-domain response regulator proteins, including the Escherichia coli nitrite/nitrate response protein NarL. In this case, transfer of a phosphate group to the N-terminal receiver domain disrupts inhibitory contacts of this domain with the C-terminal LuxR-type HTH domain, allowing dimerization and DNA binding (27, 36, 37). Studies of response regulator proteins from NarL and other LuxR family members indicate that their regulatory domains also contact the HTH 1α-2α loop and 4α-helix (28, 36, 37), similar to EL222. Although this aspect of regulation shows strong parallels between NarL and EL222, we note that they are activated quite differently. In contrast with the intramolecular mechanism that we describe for EL222, NarL activation is entirely dependent on a separate sensor protein (NarQ or NarX) that detects an environmental signal (nitrate or nitrite) (38, 39) and initiates an intermolecular phosphotransfer to NarL. Finally, although the combination of N-terminal sensory and C-terminal HTH DNA-binding domains may suggest that EL222 resembles response regulators that directly detect diffusible small ligands in the cell (35, 40), we note that some of these proteins may likely be controlled through ligand-induced protein folding (35) rather than covalent bond formation as seen in NarL and EL222.

Fig. 5.

Model for EL222 activation by blue light. In the dark, EL222 is incapable of binding DNA as the LOV domain sequesters the HTH 4α-helix and has steric conflicts with DNA if it could bind in monomeric form. The photochemical formation of a cysteinyl/flavin adduct in the LOV domain generates conformational changes that release inhibitory LOV/HTH interactions and expose the 4α helix, likely with concomitant changes in the interdomain LOV/HTH linker. The freed 4α-helix is then free to participate in HTH homodimerization upon binding DNA substrates, as observed in other HTH/DNA complexes, potentially also involving LOV/LOV interactions between EL222 monomers.

Our results also further validate a conserved aspect of LOV domain and, more generally, PAS domain signaling via the β-sheet surface. Many PAS and LOV domains use this surface for hetero- or homodimerization, whereas others bind different N- and C-terminal segments that are essential to signaling (15, 18, 25). Some of these interactions can be modulated by cofactors within the PAS/LOV domain, providing a ligand-regulated environmental switch. EL222 extends this paradigm by demonstrating that fully folded effector domains can bind to this surface, harnessing conformational changes within the LOV domain to rearrange the LOV-effector complex (without unfolding the effectors, as seen with the isolated Jα-helix in AsLOV2; ref. 15). Notably, these effector domains have different structures but appear to work through a common mechanism involving the β-sheet, potentially explaining how a single type of sensory domain can regulate a diverse group of effectors (7). Such information is particularly useful for both understanding naturally occurring LOV-regulated proteins and engineering light-regulated systems. These currently include LOV fusions to small GTPases, metabolic enzymes, DNA-binding domains, and other enzymes (8–10). All of these designed proteins have taken advantage of the well-characterized signaling mechanism of AsLOV2, including the PA-Rac1 light-activated GTPase (8). This fusion protein tethers the photosensory LOV domain closely to the effector GTPase when the Jα-helix is bound by the LOV domain, inhibiting enzymatic activity. With the knowledge of the broader principles provided here by EL222, such engineering may well be extended to an even larger range of target effectors as part of the rapidly growing toolbox of “optogenetic” tools (41) that offer precise spatial and temporal control of protein activity in vitro and in vivo.

Methods

Protein Expression and Solution Characterization.

EL222 protein samples were obtained using standard E. coli heterologous expression and affinity purification methods as detailed in SI Methods. Thin layer chromatography established that EL222 bound FMN, not FAD or riboflavin. Additional solution characterization included UV-visible absorbance spectroscopy (60 μM sample; Varian Cary 50 spectrophotometer), CD spectroscopy (15 μM sample; AVIV 62DS), and limited proteolysis (1∶43 wt∶wt ratio of chymotrypsin∶EL222). Photoexcited adduct-containing states were generated using a photographic flash (UV-vis absorbance, CD) or filtered mercury lamp (limited proteolysis).

Crystallographic Structure Determination.

Crystals of EL222 were grown using the hanging drop method, using equal volumes of 8 mg/mL EL222 (1–222) and a reservoir of 20% (wt/vol) PEG 8K, 0.1 M MOPS (pH 7.5), 0.1 M ammonium acetate. X-ray diffraction data were collected from a single crystal on beam line 7-1 at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory. The structure was solved by four-step molecular replacement using PHASER (42), with independent search models for the LOV and HTH domains (without a Jα-helix for the LOV domain). The structure of the Jα-interdomain helix was built manually as supported by difference density. The initial model of EL222 was subjected to iterative cycles of model building with COOT (43) and subsequent refinement with REFMAC5 (44) and PHENIX (45). Final R and Rfree values were 26.3% and 32.9%, respectively, with further statistics of the refinement available in Table S1.

Solution NMR Studies.

Solution NMR data were collected at University of Texas Southwestern using Varian 600 and 800 MHz spectrometers equipped with cryogenically cooled probes and laser illumination as previously described (15), with samples between 250–650 μM. NMR data were processed using NMRPipe (46) and analyzed with NMRView (47). Backbone and limited side-chain chemical shift assignments of dark-state EL222 were obtained using 1H-CH3 (V/I/L), U-2H, 13C, 15N-labeled protein and a combination of 2H-modified triple resonance and NOESY experiments. Lit-state chemical shift differences were determined using 15N/1H Scotch data to correlate dark- and lit-state chemical shifts (31), whereas lit-state 2H exchange rates were determined using interleaved dark/lit acquisition (15).

DNA-Binding Studies.

DNA-binding activity was assessed using gel shift assays using 32P-labeled dsDNA 45-bp oligonucleotide fragments of DNA located to the 5′ end of the EL222 gene, as detailed in SI Methods. Gel shift results presented in Fig. 4 used one of these fragments (oligomer 1, genomic position 983532–983577), using a photographic flash to generate the photoexcited adduct state.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Brian Zoltowski, Giomar Rivera-Cancel, and Laura Motta-Mena for assistance with data collection and analysis, and further thank all members of the Gardner laboratory for constructive comments provided on this manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM081875 to K.H.G., R01 AI07000 to H.L., T32 GM008297 supporting A.I.N.), National Science Foundation (0843662 to R.A.B.), The Robert A. Welch Foundation (I-1424 to K.H.G.), and a University of California, Irvine Chancellor’s Fellowship to H.L. The E. litoralis genome sequence data was provided by Stephen Giovannoni’s laboratory (Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR) and The J. Craig Venter Institute with grant support from The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation Microbial Genome Sequencing Project.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factor amplitudes of EL222 have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 3P7N) and NMR chemical shifts with the BioMagResBank, www.bmrb.wisc.edu (accession no. 17640).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1100262108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Taylor BL, Zhulin IB. PAS domains: Internal sensors of oxygen, redox potential, and light. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:479–506. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.479-506.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huala E, et al. Arabidopsis NPH1: A protein kinase with a putative redox-sensing domain. Science. 1997;278:2120–2123. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liscum E, Briggs WR. Mutations in the NPH1 locus of Arabidopsis disrupt the perception of phototropic stimuli. Plant Cell. 1995;7:473–485. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.4.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imaizumi T, Tran HG, Swartz TE, Briggs WR, Kay SA. FKF1 is essential for photoperiodic-specific light signalling in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2003;426:302–306. doi: 10.1038/nature02090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avila-Perez M, Hellingwerf KJ, Kort R. Blue light activates the sigmaB-dependent stress response of Bacillus subtilis via YtvA. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:6411–6414. doi: 10.1128/JB.00716-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki N, Takaya N, Hoshino T, Nakamura A. Enhancement of a sigma(B)-dependent stress response in Bacillus subtilis by light via YtvA photoreceptor. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 2007;53:81–88. doi: 10.2323/jgam.53.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crosson S, Rajagopal S, Moffat K. The LOV domain family: Photoresponsive signaling modules coupled to diverse output domains. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2–10. doi: 10.1021/bi026978l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu YI, et al. A genetically encoded photoactivatable Rac controls the motility of living cells. Nature. 2009;461:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature08241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strickland D, Moffat K, Sosnick TR. Light-activated DNA binding in a designed allosteric protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10709–10714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709610105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee J, et al. Surface sites for engineering allosteric control in proteins. Science. 2008;322:438–442. doi: 10.1126/science.1159052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Möglich A, Ayers RA, Moffat K. Design and signaling mechanism of light-regulated histidine kinases. J Mol Biol. 2009;385:1433–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salomon M, Christie JM, Knieb E, Lempert U, Briggs WR. Photochemical and mutational analysis of the FMN-binding domains of the plant blue light receptor, phototropin. Biochemistry. 2000;39:9401–9410. doi: 10.1021/bi000585+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swartz TE, et al. The photocycle of a flavin-binding domain of the blue light photoreceptor phototropin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36493–36500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halavaty A, Moffat K. N- and C-terminal flanking regions modulate light-induced signal transduction in the LOV2 domain of the blue light sensor phototropin 1 from Avena sativa. Biochemistry. 2007;46:14001–14009. doi: 10.1021/bi701543e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harper SM, Neil LC, Gardner KH. Structural basis of a phototropin light switch. Science. 2003;301:1541–1544. doi: 10.1126/science.1086810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Losi A, Kottke T, Hegemann P. Recording of blue light-induced energy and volume changes within the wild-type and mutated phot-LOV1 domain from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Biophys J. 2004;86:1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74180-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakasako M, Matsuoka D, Zikihara K, Tokutomi S. Quaternary structure of LOV-domain containing polypeptide of Arabidopsis FKF1 protein. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:1067–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.12.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zoltowski BD, et al. Conformational switching in the fungal light sensor Vivid. Science. 2007;316:1054–1057. doi: 10.1126/science.1137128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harper SM, Christie JM, Gardner KH. Disruption of the LOV-Jalpha helix interaction activates phototropin kinase activity. Biochemistry. 2004;43:16184–16192. doi: 10.1021/bi048092i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malzahn E, Ciprianidis S, Kaldi K, Schafmeier T, Brunner M. Photoadaptation in Neurospora by competitive interaction of activating and inhibitory LOV domains. Cell. 2010;142:762–772. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takahashi F, et al. AUREOCHROME, a photoreceptor required for photomorphogenesis in stramenopiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19625–19630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707692104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henikoff S, Wallace JC, Brown JP. Finding protein similarities with nucleotide sequence databases. Methods Enzymol. 1990;183:111–132. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)83009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi SH, Greenberg EP. The C-terminal region of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein contains an inducer-independent lux gene activating domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11115–11119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Möglich A, Moffat K. Structural basis for light-dependent signaling in the dimeric LOV domain of the photosensor YtvA. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:112–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Möglich A, Ayers RA, Moffat K. Structure and signaling mechanism of Per-ARNT-Sim domains. Structure. 2009;17:1282–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao X, Rosen MK, Gardner KH. Estimation of the available free energy in a LOV2-J alpha photoswitch. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:491–497. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baikalov I, et al. Structure of the Escherichia coli response regulator NarL. Biochemistry. 1996;35:11053–11061. doi: 10.1021/bi960919o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wisedchaisri G, Wu M, Sherman DR, Hol WG. Crystal structures of the response regulator DosR from Mycobacterium tuberculosis suggest a helix rearrangement mechanism for phosphorylation activation. J Mol Biol. 2008;378:227–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christie JM, Salomon M, Nozue K, Wada M, Briggs WR. LOV (light, oxygen, or voltage) domains of the blue-light photoreceptor phototropin (nph1): Binding sites for the chromophore flavin mononucleotide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8779–8783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rubinstenn G, et al. NMR experiments for the study of photointermediates: Application to the photoactive yellow protein. J Magn Reson. 1999;137:443–447. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bai Y, Milne JS, Mayne L, Englander SW. Primary structure effects on peptide group hydrogen exchange. Proteins. 1993;17:75–86. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brudler R, et al. PAS domain allostery and light-induced conformational changes in photoactive yellow protein upon I2 intermediate formation, probed with enhanced hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. J Mol Biol. 2006;363:148–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Da Re S, et al. Phosphorylation-induced dimerization of the FixJ receiver domain. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:504–511. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu J, Winans SC. The quorum-sensing transcriptional regulator TraR requires its cognate signaling ligand for protein folding, protease resistance, and dimerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1507–1512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang JH, Xiao G, Gunsalus RP, Hubbell WL. Phosphorylation triggers domain separation in the DNA binding response regulator NarL. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2552–2559. doi: 10.1021/bi0272205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eldridge AM, Kang HS, Johnson E, Gunsalus R, Dahlquist FW. Effect of phosphorylation on the interdomain interaction of the response regulator, NarL. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15173–15180. doi: 10.1021/bi026254+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walker MS, DeMoss JA. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation catalyzed in vitro by purified components of the nitrate sensing system, NarX and NarL. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:8391–8393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schroder I, Wolin CD, Cavicchioli R, Gunsalus RP. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of the NarQ, NarX, and NarL proteins of the nitrate-dependent two-component regulatory system of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4985–4992. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.16.4985-4992.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Urbanowski ML, Lostroh CP, Greenberg EP. Reversible acyl-homoserine lactone binding to purified Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:631–637. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.3.631-637.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moglich A, Moffat K. Engineered photoreceptors as novel optogenetic tools. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2010;9:1286–1300. doi: 10.1039/c0pp00167h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Delaglio F, et al. NMRPipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson BA, Blevins RA. NMRView: A computer program for the visualization and analysis of NMR data. J Biomol NMR. 1994;4:603–614. doi: 10.1007/BF00404272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.