Abstract

Purpose

We evaluated dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DSC-MRI) using gadoteridol in comparison to the iron oxide nanoparticle blood pool agent, ferumoxytol in patients with glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) who received standard radiochemotherapy (RCT).

Methods and Materials

Fourteen patients with GBM received standard RCT and underwent 19 MRI sessions that included DSC-MRI acquisitions with gadoteridol on day 1 and ferumoxytol on day 2. Relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV) values were calculated from DSC data obtained from each contrast agent. T1-weighted acquisition post-gadoteridol administration was used to identify enhancing regions.

Results

In 7 MRI sessions of clinically presumptive active tumor, gadoteridol-DSC showed low rCBV in 3 and high rCBV in 4, while ferumoxytol-DSC showed high rCBV in all 7 sessions (p=0.002). After RCT, 7 MRI sessions showed increased gadoteridol contrast enhancement on T1-weighted scans coupled with low rCBV without significant differences between contrast agents (p=0.9). Based on post-gadoteridol T1-weighted scans, DSC-MRI, and clinical presentation four patterns of response to RCT were observed: 1) regression, 2) pseudoprogression, 3) true progression, and 4) mixed response.

Conclusion

We conclude that DSC-MRI with a blood-pool agent such as ferumoxytol may provide a better monitor of tumor rCBV than DSC-MRI with gadoteridol. Lesions demonstrating increased enhancement on T1-weighted MRI coupled with low ferumoxytol rCBV, are likely exhibiting pseudoprogression, while high rCBV with ferumoxytol is a better marker than gadoteridol for determining active tumor. These interesting pilot observations suggest that ferumoxytol may differentiate tumor progression from pseudoprogression, and warrant further investigation.

Keywords: Blood-brain barrier, dynamic susceptibility- weighted contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, glioblastoma multiforme, pseudoprogression, radiochemotherapy

Introduction

The term “pseudoprogression” is used to describe the phenomenon of subacute imaging changes in human glioma subsequent to radiochemotherapy (RCT) with or without associated clinical sequelae.1 Increased or new enhancement after RCT can reflect pseudoprogression which can occur up to 6 months after treatment,2, 3 as well as true tumor progression which can happen anytime after treatment. However, patients with pseudoprogression, unlike true tumor progression, recover or stabilize spontaneously, generally without any changes in their treatment paradigm.1 The etiology of pseudoprogression is thought to be due to vascular and oligodendroglial injury leading to inflammation and increased permeability of the blood brain barrier (BBB).4–6 Varying incidences of pseudoprogression are reported, but recent reports 7, 8 estimate it to be as high as 30% within the first few months after RCT. Distinguishing true tumor progression from pseudoprogression is crucial in disease management decisions. Standard T2-weighted and gadolinium-based contrast agent (GBCA)-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sequences cannot reliably distinguish true tumor progression and pseudoprogression. 1, 7

Dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI (DSC-MRI, also referred to as perfusion-weighted imaging) measurement of relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV) has been used for glioma grading9–12 assessment of glioma patient prognosis 12–16 and differentiation of recurrent tumor from radiation necrosis.17–19 High rCBV indicates active neovascularization and viable tumor.15 Accurate measurement of rCBV using standard DSC modeling approaches relies on intravascular localization of contrast agent in the tissue of interest. This condition is compromised by the leaky blood-brain barrier (BBB) present within malignant brain tumors, especially following RCT. Rapid extravasation of GBCA from blood vessels into the extravascular/extracellular space can confound the rCBV estimation obtained using DSC-MRI. 20 Therefore, DSC-MRI using GBCA can falsely estimate low rCBV in some patients with progressive disease.18, 19

Ferumoxytol, an ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle approved by the food and drug administration for iron replacement therapy, is gaining utility in brain imaging.21 Ferumoxytol acts as a blood-pool agent in the short term (minutes to hours), so its vascular localization is not compromised by the leaky BBB in tumors.22 The differences in vascular leakage between ferumoxytol and GBCA may be accentuated by anti-angiogenesis agents which can markedly affect tumor permeability to GBCA.22 Additionally, unlike other iron oxide nanoparticle contrast agents, ferumoxytol is safe when given as a fast bolus injection.23 For these reasons we hypothesized that ferumoxytol has the potential to measure rCBV more accurately than GBCA. In this report we present our preliminary results comparing rCBV estimated from DSC-MRI with ferumoxytol versus GBCA in patients with glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) for the potential of differentiating pseudoprogression from true tumor progression.

Materials and Methods

Between April 2007 and December 2008 14 patients with GBM were prospectively studied in one of three different research imaging protocols sponsored by the National Cancer Institute and approved by the Oregon Health & Science University institutional review board. Protocols 2753, 2864 and 1562 all compare anatomical and dynamic MRI using GBCA versus ferumoxytol. Informed written consent was obtained from all patients.

Inclusion criteria for this analysis included: (a) histologically proven GBM (World Health Organization classification, grade IV); (b) standard postsurgical treatment - radiotherapy combined with concomitant and adjuvant treatment with temozolomide; and (c) increased or new enhancement on conventional GBCA-enhanced T1-weighted MRI post-RCT.

Four patients on protocol #2753 underwent DSC imaging twice, first after surgery but before RCT, when residual tumor was detected, and second within a week after completion of RCT. Another patient underwent DSC-MRI twice after completion of RCT (2 and 28 months), due to increased enhancement on conventional MRI. The remaining patients had DSC-MRI once (only after completion of RCT), and were entered in the study because of increased/new enhancement on post-RCT follow up MRI. Patient information is provided in Table 1. As shown in the table, in the majority of cases, rCBV estimation was performed within 1 month after the increase of GBCA enhancement seen after completion of RCT.

Table 1.

Patients characteristics and classification.

| Pt. no. | DSC-MR Sessions, pre or post RCT |

Groups | Fe - rCBV | Gd - rCBV | Ferumoxytol doses, 1, 2mg/kg and75mg |

Age, years | Sex | Surgery | RT, Gy | Interval from RCT to increase of enh., months |

Interval from RCT to DSC-MRI, months |

Antiangiogenic treatment |

Survival from RCT, months |

Survival from DSC-MRI, months |

Dexamethasone, mg/day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 pre | B | ↑ | ↓ | 2 | 53 | M | R | 56 | ↓ enh. | <1 | − | 24+ | 24+ | 4 |

| 2 post | A | ↓ | ↓ | 2 | 0 | ||||||||||

| 2 | 3 post | C1 | ↓ | ↓ | 1 | 56 | M | R | 59 | 2 | 2 | − | 40+ | 38+ | 0 |

| 4 post | B | ↑ | ↓ | 75 | 28 | 28 | + | 12+ | 0 | ||||||

| 3 | 5 pre | B | ↑ | ↑ | 2 | 68 | M | R | 59 | <1 | <1 | + | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 6 post | C2 | ↓↑ | ↓ | 2 | 0 | ||||||||||

| 4 | 7 post | C1 | ↓ | ↓ | 1 | 64 | M | R | 59 | 2 | 2 | − | 30+ | 28+ | 0 |

| 5 | 8 post | C1 | ↓ | ↓ | 1 | 68 | M | R | 60 | <1 | 4 | − | 30+ | 26+ | 0 |

| 6 | 9 pre | B | ↑ | ↓ | 2 | 59 | F | Bi | 59 | <1 | <1 | + | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 10 post | B | ↑ | ↑ | 2 | 12 | ||||||||||

| 7 | 11 post | C1 | ↓ | ↓ | 1 | 35 | M | R | 59 | 1 | 2 | + | 24+ | 22+ | 0 |

| 8 | 12 post | C1 | ↓ | ↓ | 1 | 73 | M | R | 60 | 3 | 3 | + | 12 | 9 | 0 |

| 9 | 13 post | C1 | ↓ | ↓ | 75 | 49 | M | R | 60 | 1 | 3 | + | 18 | 15 | 0 |

| 10 | 14 post | C2 | ↓↑ | ↓ | 75 | 51 | M | Bi | 59 | <1 | 1 | + | 8 | 7 | 16 |

| 11 | 15 pre | B | ↑ | ↑ | 2 | 46 | M | Bi | 59 | <1 | <1 | + | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| 16 post | C2 | ↓↑ | ↓ | 2 | 12 | ||||||||||

| 12 | 17 post | C1 | ↓ | ↓ | 75 | 50 | M | R | 59 | 5 | 5 | + | 19+ | 14+ | 2 |

| 13 | 18 post | B | ↑ | ↑ | 75 | 46 | F | R | 59 | 11 | 11 | + | 15 | 4 | 4 |

| 14 | 19 post | C2 | ↓↑ | ↑ | 75 | 19 | M | R | 59 | 1 | 1 | + | 11 | 10 | 0 |

Abbreviations:

pre – DSC-MRI before RCT

post – DSC-MRI after RCT

M – male

F – female

R – resection

Bi - biopsy

Fe – rCBV – rCBV measured by DSC-MRI using ferumoxytol

RCT - radiochemotherapy

enh. – enhancement

↑ - increase

↓ - decrease

↓↑ - both decrease and increase (mixed)

A - Decrease of tumor enhancement on contrast enhanced T1-weighted MRI right after RCT in comparison to pre-RCT

B - Residual enhancing tumor on contrast enhanced T1-weighted MRI after surgery but before RCT or increase an enhancement 11 and 28 months after completion of RCT with neurologic worsening or rapid progressive clinical and radiologic deterioration within 1 month after RCT leading to death

C1 – Entire increased enhancing area after RCT has low rCBV

C2 – Predominantly low rCBV with high region at periphery of enhancing area or decline of high rCBV after RCT compare to pre-RCT, but still >1.75.

Magnetic resonance imaging

The 14 patients underwent a total of 19 MRI sessions. Each session consisted of two consecutive days of MRI scanning. On the first day, pre and post-contrast T1-weighted images and DSC-MRI were acquired using gadoteridol gadolinium (III) chelate (ProHance®, Bracco Diagnostic Inc, Princeton, N.J., USA). On the following day same MRI sequences were acquired using ferumoxytol (provided by AMAG Pharmaceuticals Inc, Cambridge MA, USA).

Eighteen of 19 MRI sessions were conducted using a 3T whole-body MR system (TIM TRIO, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with a body RF coil transmit and12-channel phased array head RF receiver coil. One MRI session was performed using a 7T MR system (MAGNETOM 7T, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with an 8-channel phased array transmit/receive RF head coil (Rapid Biomedical, Wurzburg, Germany).

For DSC-MRI, dynamic T2*-weighted images were acquired using a gradient-echo echo-planar imaging pulse sequence (repetition time = 1500 ms, echo time = 20 ms, flip angle 45°, field of view 192 × 192 mm, matrix 64 × 64, and 27 interleaved slices (3T) or 13 slices (7T) with 3 mm thickness and 0.9 mm gap). After an initial baseline period of 7 series of 27 image slices (11 s), a rapid bolus of contrast agent was administered intravenously using a power injector (Spectris Solaris - MEDRAD INC, PA, USA) through an 18 gauge intravenous line at a rate of 3 ml/s; followed immediately by 20 ml of saline flush at the same rate. DSC data collection continued for 90 series (2 min 21 s). Gadoteridol was injected at a dose of 0.1 mmol/kg of body weight. Ferumoxytol was given as a dose of either 2 mg/kg (protocol #2753), or 1 mg/kg (protocol #2864), or in a constant volume of 2.5 ml diluted with 2.5 ml of saline (75 mg) regardless of body weight (protocol #1562).

T1-weighted images were collected pre and 20 minutes post-gadoteridol using a magnetization prepared rapid gradient read out (MPRAGE TE2.7/TR2300/TI900).

Imaging analysis

All first-pass DSC-MRI data were processed using Lupe (Lund, Sweden) perfusion image analysis software. The arterial input function was determined from the middle cerebral artery contralateral to the enhancing lesion. Color-coded rCBV maps were created on a voxel-wise basis uncorrected for contrast leakage, and were overlaid onto the post-gadoteridol T1-weighted images. Within the enhancing lesion, a single voxel (3 × 3 × 3 mm) region of interest (ROI) with the highest rCBV value on the ferumoxytol - rCBV parametric map and the same ROI on the gadoteridol-rCBV parametric map were analyzed using ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij). Areas depicting major vessels were excluded from ROIs. The rCBV values were calculated as the ratio of highest lesion blood volume to normal appearing contralateral white matter blood volume (mean of 3 ROIs). Previous studies have shown that a threshold rCBV ratio of 1.75, measured by DSC-MRI using GBCA, is predictive of time to progression or survival.13, 15 Therefore, in our study, rCBV > 1.75 was considered high and rCBV < 1.75 as low.

Statistical analysis

Mean and standard deviation of rCBV measurements for each group and both contrast agents were obtained. Student’s paired t - test was used to determine whether there were significant differences in measured rCBV values between ferumoxytol- and gadoteridol-DSC-MRI in the same group of perfusion data. The difference in rCBV values, with both contrast agents, between groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The 14 GBM patients in this analysis underwent a total of 19 dynamic imaging sessions. Each of the 19 MRI sessions was categorized into one of three groups based on the patient’s clinical course and changes in the appearance of the enhancing lesion on anatomical MR imaging (Table 1): Group A, tumor regression (one session); Group B, active tumor (7 sessions); and Group C, equivocal response (11 sessions).

Group A: Tumor Regression

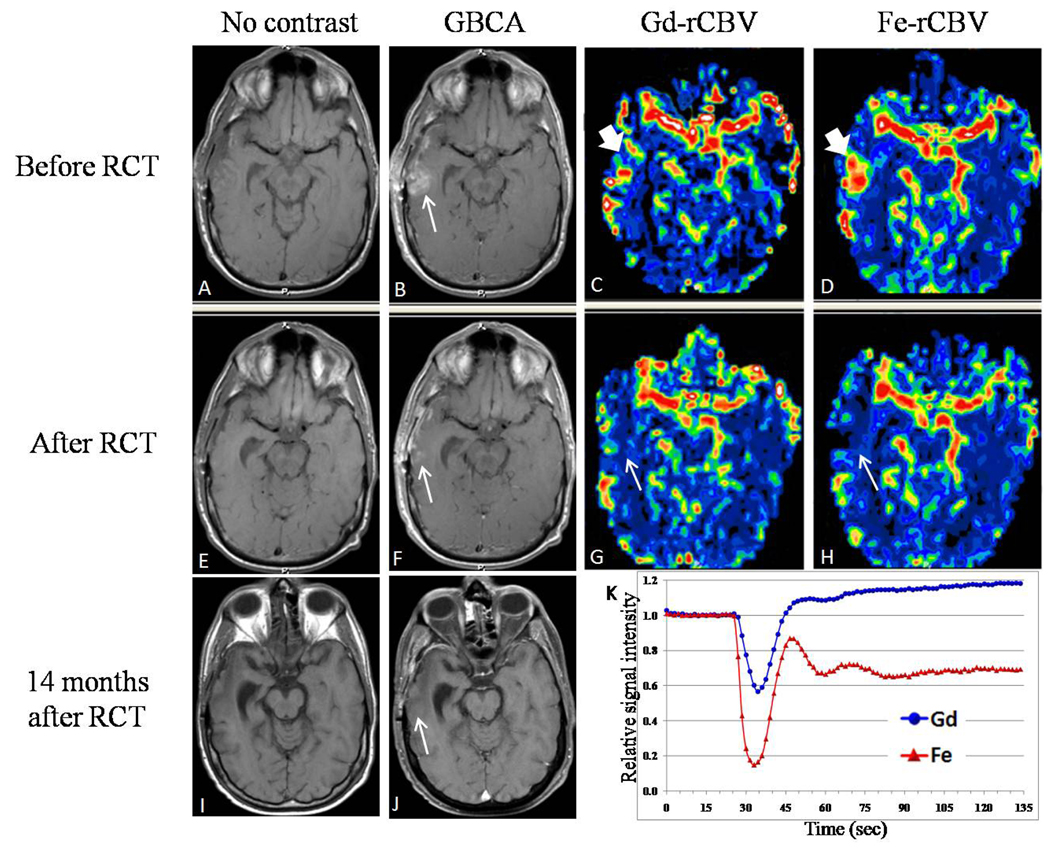

Decreased area of enhancement on the first GBCA-enhanced T1-weighted MRI after completion of RCT, in comparison to pre-RCT MRI, with clinical improvement, were the criteria for tumor regression; this was seen in one imaging session (Figure 1). The rCBV estimated by DSC-MRI using ferumoxytol declined in this case from high (15.6) before RCT to low (0.8) after (Figure 1D, H), while gadoteridol-rCBV declined from 1.6 to 1.1 (Figure 1C,G). This subject had no further progression on follow up MRI to date (24 months post-RCT).

Figure 1.

Regression after radiochemotherapy (RCT) (Patient #1 in Table 1). (A, E, I) T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) before and (B, F, J) after gadoteridol (Gd) administration. (A, B) MRI after surgery but before RCT demonstrates area of enhancement in the right temporal lobe (arrow). Relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV) in the enhancing area was lower on the Gd-rCBV parametric map (C) compared to the ferumoxytol (Fe)-rCBV map (D) (bold arrow). (E, F) MRI after completion of RCT revealed decreased enhancement (F, arrow) with low rCBV on Gd-rCBV (G) and Fe-rCBV parametric maps (H) (arrow). (I, J) MRI 14 months after completion of RCT showed resolution of enhancement. (K) First-pass time-intensity curves of the perfusions C and D demonstrate post-bolus increasing signal above the baseline when Gd was used while ferumoxytol post-bolus signal intensity was below the baseline and remains stable.

Group B: Active Tumor – residual tumor plus tumor progression

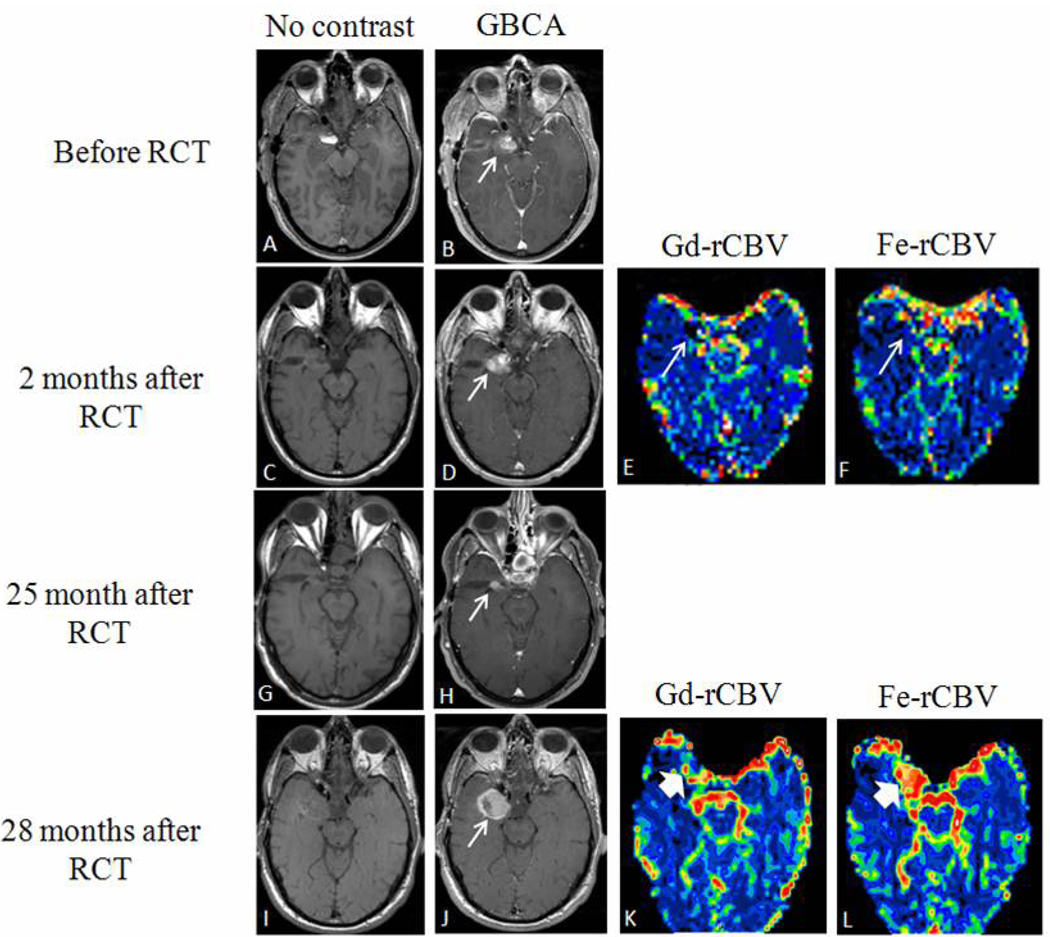

Four MRI sessions performed after surgery, but before RCT showed residual enhancing tumor on GBCA-enhanced T1-weighted MRI (see Figures 1A–B,2A–B,3A–B). Three MRI sessions performed after RCT were included in the active tumor group based on clinical deterioration coupled with increased GBCA enhancement. One of these patients progressed and died within 1 month of RCT, while two showed worsening clinical condition 11 and 28 months after RCT, respectively, accompanied by increased areas of enhancement on GBCA-enhanced T1-weighted MRI (Table 1, Figure 2I–L). Bevacizumab antiangiogenic treatment was started in all 3 patients right after the DSC-MRI study suggested tumor progression; nevertheless 2 of the patients died in 1 and 4 months respectively. Only 1 patient is alive at the publication date of this manuscript, 12 months after tumor progression.

Figure 2.

Pseudoprogression followed by true tumor progression (Patient #2 in Table 1).

(A, C, G, I) T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) before and (B, D, H, J) after gadoteridol (Gd). (A, B) MRI after surgery but before radiochemotherapy (RCT) demonstrates residual enhancement (arrow). (C, D) MRI 2 months after RCT shows increased area of enhancement with low relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV) on both Gd (E) and ferumoxytol (Fe) parametric maps (F) (arrow). (G, H) Adjuvant temozolomide treatment was continued and enhancement decreased on MRI 25 months after the end of RCT (arrow). (I, J) Area of increased enhancement on MRI 28 months after RCT (arrow) coincided with high Fe-rCBV (L) and low Gd-rCBV (K) (bold arrows).

Figure 3.

Mixed response to radiochemotherapy (RCT) (Patient #14 in Table 1). (A) T1-weighted contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) before surgery demonstrated glioblastoma multiforme lesion which decreased in size after surgery (B). (C) MRI 1 month after RCT showed increased enhancement, with low relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV) within the lesion and a thin rim of high rCBV with ferumoxytol (Fe) and lower with gadoteridol (Gd) (D) (E) (arrow).

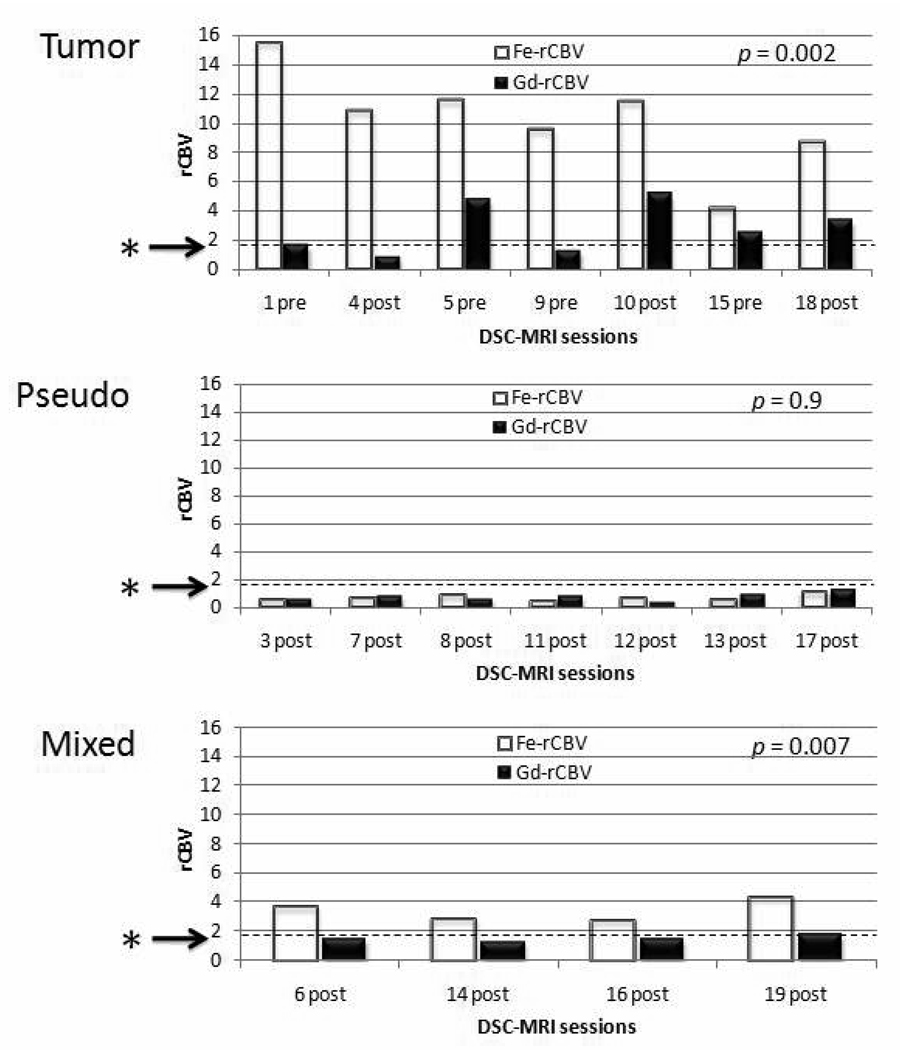

The ferumoxytol- rCBV values for all studies designated as active tumor were universally high (mean 10.3 ± 3.4). Gadoteridol-rCBV values were high (>1.75) in 4 of 7 and low (<1.75) in 3 of 7 perfusion studies (mean 2.7 ± 1.7) (Figures 4 and 5). The difference between ferumoxytol-rCBV and gadoteridol-rCBV values was significant (P = 0.002). There was concordance between the areas of high rCBV using ferumoxytol and the areas of GBCA-enhancement in all 7 MRI sessions; this was not true for gadoteridol rCBV. Even in two patients with known residual tumor prior to treatment with RCT, gadoteridol-rCBV was low, whereas the ferumoxytol-rCBV was elevated.

Figure 4.

Comparison of relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV) acquired by dynamic susceptibility contrast magnetic resonance imaging (DSC-MRI) using ferumoxytol versus gadoteridol.

Rapidly growing tumors are assocated with rCBV > 1.75 13, 15 indicated by the starred arrows. The rCBV obtained using gadoteridol was always lower than using ferumoxytol in tumor (P=0.002) and the mixed response group (P=0.007), but there was no difference between contrast agents in the pseudoprogression group (P=0.9).

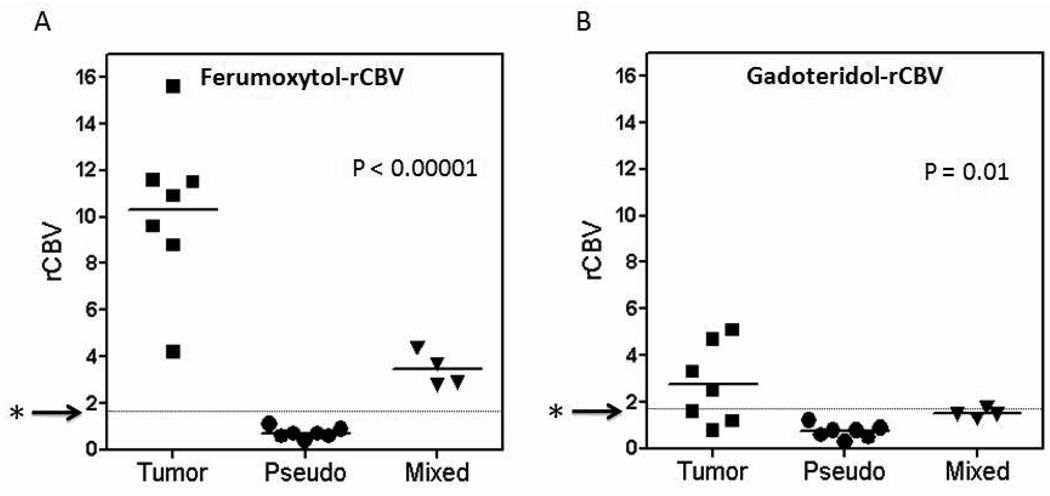

Figure 5.

Comparison of relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV) between tumor, pseudoprogression and mixed response groups.

(A) Dynamic susceptibility contrast magnetic resonance imaging (DSC-MRI) using ferumoxytol revealed high rCBV in the tumor group (> 4.2), low in the pseudoprogression group (< 1.1) and intermediate in the mixed response group. Rapidly growing tumors are assocated with rCBV > 1.7513, 15 indicated by the starred arrows. (B) DSC-MRI using gadoteridol showed low rCBV (< 1.7) in 3 of 7 scans in the tumor group, low rCBV in all pseudoprogression scans (< 1.2), and low in 3 of 4 mixed response scans. Differences between groups were significant ( P<0.00001 for ferumoxytol; P=0.01 for gadoteridol).

Group C: Equivocal Tumor Activity

This group consisted of the remaining 11 MRI sessions which did not fit the criteria for regression (group A) or progression (group B). We investigated whether we could determine the clinical status of patients in this group by imaging criteria alone.

The main imaging finding for group C was the discordance between the areas of new/increasing enhancement on GBCA-enhanced T1-weighted MRI and results of perfusion studies. All 11 imaging sessions showed new or increased enhancement on GBCA-enhanced T1-weighted MRI after RCT. In 7 of 11 MRI sessions, areas of new/increasing enhancement coincided with low ferumoxytol-rCBV (Figure 2C–F) and were categorized to subgroup C1: pseudoprogression. In 3 MRI sessions, high ferumoxytol-rCBV was seen only at the periphery of the GBCA enhancing areas and these were categorized to subgroup C2: mixed response. Figure 3 shows a typical mixed response subject (#14 in Table 1). A fourth subject (#11 in Table 1) was also categorized as mixed response because of contrast enhancement increase, with concurrent ferumoxytol-rCBV decline after completion of RCT in comparison to pre-RCT (from 4.2 to 2.8). Gadoteridol-rCBV estimates in the mixed response group were low in three patients (<1.75) and high in one (Figure 4).

In the presumptive pseudoprogression subgroup (C1), both ferumoxytol-rCBV (mean = 0.7 + 0.2) and gadoteridol-rCBV (mean = 0.7 ± 0.3) were low, with no statistical difference (P = 0.9) (Figures 4 and 5). The average interval between the end of RCT and increased contrast enhancement on GBCA-enhanced MRI in this subgroup was 2.1 months (range <1 to 1–5 months). One of these patients (Table 1, patient #9) underwent re-operation for the increasing enhancement noted on MRI, which proved to be necrosis. All patients had regression or stabilization of contrast enhancement for a mean of 19.4 months (range 8 – 26 months post-DSC-MRI study) without changes in their chemotherapy regime (four patients received antiangiogenic treatment in addition to chemotherapy right after the DSC-MRI study). Three patients had later areas of increasing enhancement at 11, 17 and 28 months post-RCT; the first two died within 1 month (12 and 18 months post-RCT, respectively). Images for the third subject (28 months) are included in group B. (Figure 2I–L) The remainder of the patients in this subgroup are clinically stable to date, with shortest follow up equal to 19 months.

In the mixed response subgroup (C2), ferumoxytol-rCBV was high in all imaging sessions (mean = 3.4 ± 0.7), while the gadoteridol-rCBV was inconsistent (high in one and low in three perfusion studies, mean = 1.5 ± 0.2) (Figure 4). All patients in this group had perfusion imaging </= one month after RCT. Bevacizumab antiangiogenic treatment was started in all four patients right after DSC-MRI study, in addition to their chemotherapy regimen. Three subsequently died due to tumor progression at 3, 8 and 11 months post-RCT (mean post-RCT survival 7.3 months), and one died due to intestinal perforation, possibly related to bevacizumab. 24 One patient is still alive at the publication date of this manuscript (3 months after RCT).

A one-way ANOVA was performed to evaluate the difference in rCBV values between active tumor, pseudoprogression and mixed response groups. The difference was highly statistically significant for ferumoxytol (P = 0.0001) and significant for gadoteridol (P = 0.02). (Figure 5)

Discussion

The ability to differentiate true tumor progression from pseudoprogression is critically important since the prognosis and treatment are completely different. Many non-invasive methods as positron emission tomography 25, 26, magnetic resonance spectroscopy 27–29 and perfusion-weighted MRI 17–19 have attempted this differentiation, although all have limitations. Perfusion-weighted MRI using GBCA has been used with variable success for assessing tumor grade, 9–12 survival, and overall outcome 12–16 in patients with high grade gliomas. Despite ongoing research, the predictive value of these tools is still far from acceptable.

Increased areas of GBCA enhancement on T1-weighted MRI represent leaky capillaries and altered BBB permeability, rather than specifically denoting tumor growth. Extravasation of GBCA after bolus injection during DSC-MRI results in T1 shortening effect which competes with the susceptibility-induced signal decrease. This effect is clearly demonstrated in Figure 1K. The initial post-bolus phase (25–45 sec) is dominated by T2* effects and manifests as a signal intensity decrease from baseline. Following the first pass (>45 sec), the T1 effect becomes dominant and manifests as a signal intensity increase above baseline. This does not occur when the contrast agent remains intravascular as is the case for ferumoxytol which produced large susceptibility-induced signal decreases throughout the post-bolus time points (>25 sec). Ferumoxytol behaves differently than GBCAs due to its larger molecular size - up to 50nm (compared to the 1nm gadolinium chelate). Early after intravenous injection, ferumoxytol distributes evenly in the blood pool and the extravasation rate through BBB defects is orders of magnitude lower than for GBCA.23 We have previously demonstrated that rCBV estimation using ferumoxytol is reliable and does not require leakage correction, based on extravasation, in conditions where the BBB is disrupted. 21, 22

Combining their clinical course, anatomical MRI and rCBV measurements, we have categorized subjects into 4 different groups (Table 1). Group A, (one patient) represented regression. Group B, consisting of 7 MRI sessions, represented residual tumor and/or disease progression. The gadoteridol-rCBV was low in 3 of 7 sessions in this group, whereas ferumoxytol-rCBV was consistently elevated. The ferumoxytol-rCBV was significantly higher than gadoteridol-rCBV both on an individual basis and as a comparison of means (P = 0.002). While subjects in this group clearly had active disease, in 43% of the cases gadoteridol-rCBV was low and failed to differentiate from pseudoprogression and was thus not predictive of tumor progression.

Subjects in subgroup C1, patients with documented reduction of GBCA enhancement after an initial increase (e.g. pseudoprogression) had a progression-free survival of 23+ months (post-RCT), longer than the median survival documented in major trials.30 These subjects all had low rCBV values using both ferumoxytol and gadoteridol. These data suggest that low ferumoxytol-rCBV, in the setting of increased GBCA enhancement is characteristic of pseudoprogression. The time-line for occurrence of pseudoprogression is not sharp. Chamberlin and colleagues3 found necrosis, with no evidence of recurrence, in surgical specimens of 14% of patients with malignant glioma within 6 months after radiotherapy, representing half the patients operated upon during that interval for radiologic progression. The six-month mark correlates well with the timing of our presumed pseudoprogression group (1–5 months). In our small sample of patients with GBM, presumed pseudoprogression occurred in 7 of 13 patients (54%) who showed an increase or new enhancement on post-RCT conventional MRI.

Group C2 (mixed responders) consisted of 4 patients, all of whom died from either tumor progression (3/4; mean post-RCT survival of 7.3 months) or from a non-central nervous system-related complication (1/4). While the small number precludes any firm conclusions, the poor survival in this group compared to the pseudoprogression group (C1) points towards a more malignant clinical course. The ferumoxytol-rCBV was either high predominantly at the periphery of the GBCA enhancing area, or decreased in comparison to pre-RCT, but still >1.75 compared to normal brain. Thus ferumoxytol was superior to gadoteridol for indicating progressive tumor in group C2.

rCBV values were consistently lower in gadoteridol- compared to ferumoxytol-based perfusion (Figures 4 and 5). This finding was statistically significant for groups B (active tumor) and subgroup C2 (mixed response), but not in subgroup C1 (pseudoprogression). Based on our study, high gadoteridol-rCBV most likely represents tumor recurrence/progression while low gadoteridol-rCBV can be seen in cases of pseudoprogression as well as in actively growing tumors. This finding is concordant with recent data reported. 18, 19 Our explanation for the rather consistent lower gadoteridol-rCBV across all groups is the phenomenon of gadoteridol extravasation. Several creative methods have been proposed to minimize the confounding effect of GBCA extravasation on DSC perfusion analyses.19, 20, 31 We suggest that a simpler and more reliable approach for rCBV measurement is to use a blood pool agent that does not leak through the BBB during DSC-MRI data acquisition. Our results suggest that ferumoxytol-rCBV is superior to gadoteridol-rCBV in this regard.

Conclusion

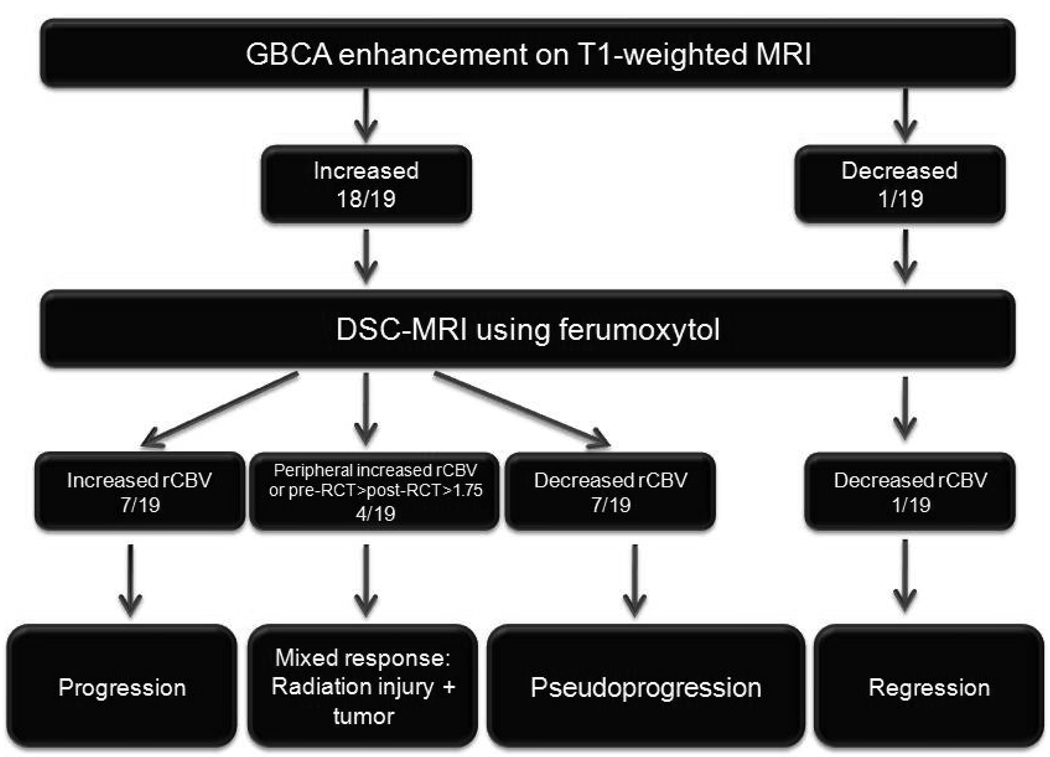

Based on our preliminary results, we hypothesize that ferumoxytol-based DSC-MRI may differentiate true tumor progression from pseudoprogression and this may greatly improve disease management. If physicians are able to accurately identify pseudoprogression from true tumor progression, they will be able to choose the proper course of treatment, reducing overall costs and improving patient outcome. We propose 4 patterns of response and their imaging findings following RCT: 1) regression - decreasing enhancement with low ferumoxytol rCBV; 2) true progression - increasing enhancement with high ferumoxytol rCBV; 3) pseudoprogression - increasing enhancement with low ferumoxytol rCBV; 4) mixed response - either high ferumoxytol-rCBV, only at the periphery of large areas of GBCA enhancement, or decreased ferumoxytol-rCBV after RCT compared to pre-RCT, but still >1.75 (Figure 6). We suggest that ferumoxytol-based perfusion-weighted MRI holds great promise to evaluate tumor behavior, response to therapy, and the effects of different angiogenesis inhibitors in human GBM, with potential use in other brain tumors as well.

Figure 6.

Algorithm of evaluation and classification of response to radiochemotherapy by conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using gadolinium-based contrast agent and dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI using ferumoxytol.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Veterans Administration merit review grant and by National Institute of Health grants CA137488, NS53468, and NS44687 to EAN. Special thanks to Paula Jacobs, Gerald Wolf, James L. Tatum, Jason Weinstein, Eric Thompson, Matthew Hunt, Aliana Kim and Emily Hochhalter for their helpful input in the development of this report.

Abbreviations

- RCT

radiochemotherapy

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- BBB

blood brain barrier

- GBCA

gadolinium-based contrast agent

- DSC-MRI

Dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI

- rCBV

relative cerebral blood volume

- ROI

regions of interest

- GBM

glioblastoma multiforme

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest. There is a sponsored research agreement to OHSU from AMAG Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Brandsma D, Stalpers L, Taal W, et al. Clinical features, mechanisms, and management of pseudoprogression in malignant gliomas. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:453–461. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaskis C, Neyns B, Michotte A, et al. Pseudoprogression after radiotherapy with concurrent temozolomide for high-grade glioma: clinical observations and working recommendations. Surg Neurol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chamberlain MC, Glantz MJ, Chalmers L, et al. Early necrosis following concurrent Temodar and radiotherapy in patients with glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2007;82:81–83. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9241-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tofilon PJ, Fike JR. The radioresponse of the central nervous system: a dynamic process. Radiat Res. 2000;153:357–370. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2000)153[0357:trotcn]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong CS, Van der Kogel AJ. Mechanisms of radiation injury to the central nervous system: implications for neuroprotection. Mol Interv. 2004;4:273–284. doi: 10.1124/mi.4.5.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordal RA, Nagy A, Pintilie M, et al. Hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 target genes in central nervous system radiation injury: a role for vascular endothelial growth factor. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3342–3353. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandes AA, Tosoni A, Spagnolli F, et al. Disease progression or pseudoprogression after concomitant radiochemotherapy treatment: pitfalls in neurooncology. Neuro Oncol. 2008;10:361–367. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandes AA, Franceschi E, Tosoni A, et al. MGMT promoter methylation status can predict the incidence and outcome of pseudoprogression after concomitant radiochemotherapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2192–2197. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aronen HJ, Gazit IE, Louis DN, et al. Cerebral blood volume maps of gliomas: comparison with tumor grade and histologic findings. Radiology. 1994;191:41–51. doi: 10.1148/radiology.191.1.8134596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knopp EA, Cha S, Johnson G, et al. Glial neoplasms: dynamic contrast-enhanced T2*-weighted MR imaging. Radiology. 1999;211:791–798. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.3.r99jn46791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugahara T, Korogi Y, Kochi M, et al. Correlation of MR imaging-determined cerebral blood volume maps with histologic and angiographic determination of vascularity of gliomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1479–1486. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.6.9843274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lev MH, Ozsunar Y, Henson JW, et al. Glial tumor grading and outcome prediction using dynamic spin-echo MR susceptibility mapping compared with conventional contrast-enhanced MR: confounding effect of elevated rCBV of oligodendrogliomas [corrected] AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:214–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao Y, Tsien CI, Nagesh V, et al. Survival prediction in high-grade gliomas by MRI perfusion before and during early stage of RT [corrected] Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:876–885. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danchaivijitr N, Waldman AD, Tozer DJ, et al. Low-grade gliomas: do changes in rCBV measurements at longitudinal perfusion-weighted MR imaging predict malignant transformation? Radiology. 2008;247:170–178. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2471062089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Law M, Young RJ, Babb JS, et al. Gliomas: predicting time to progression or survival with cerebral blood volume measurements at dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging. Radiology. 2008;247:490–498. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2472070898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oh J, Henry RG, Pirzkall A, et al. Survival analysis in patients with glioblastoma multiforme: predictive value of choline-to-N-acetylaspartate index, apparent diffusion coefficient, and relative cerebral blood volume. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;19:546–554. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barajas RF, Jr, Chang JS, Segal MR, et al. Differentiation of Recurrent Glioblastoma Multiforme from Radiation Necrosis after External Beam Radiation Therapy with Dynamic Susceptibility-weighted Contrast-enhanced Perfusion MR Imaging. Radiology. 2009 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2532090007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoefnagels FW, Lagerwaard FJ, Sanchez E, et al. Radiological progression of cerebral metastases after radiosurgery: assessment of perfusion MRI for differentiating between necrosis and recurrence. J Neurol. 2009;256:878–887. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5034-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu LS, Baxter LC, Smith KA, et al. Relative cerebral blood volume values to differentiate high-grade glioma recurrence from posttreatment radiation effect: direct correlation between image-guided tissue histopathology and localized dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging measurements. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:552–558. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sorensen AG. Perfusion MR imaging: moving forward. Radiology. 2008;249:416–417. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2492081429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neuwelt EA, Varallyay CG, Manninger S, et al. The potential of ferumoxytol nanoparticle magnetic resonance imaging, perfusion, and angiography in central nervous system malignancy: a pilot study. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:601–611. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000255350.71700.37. discussion 611-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varallyay CG, Muldoon LL, Gahramanov S, et al. Dynamic MRI using iron oxide nanoparticles to assess early vascular effects of antiangiogenic versus corticosteroid treatment in a glioma model. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:853–860. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinstein J, Varallyay CG, Dosa E, et al. Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Diagnostic Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Potential Therapeutic Applications in Neurooncology and CNS Inflammatory Pathologies, a Review. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009 doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.192. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saif MW, Elfiky A, Salem RR. Gastrointestinal perforation due to bevacizumab in colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1860–1869. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rachinger W, Goetz C, Popperl G, et al. Positron emission tomography with O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-l-tyrosine versus magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of recurrent gliomas. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:505–511. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000171642.49553.b0. discussion 505–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsuyuguchi N, Takami T, Sunada I, et al. Methionine positron emission tomography for differentiation of recurrent brain tumor and radiation necrosis after stereotactic radiosurgery--in malignant glioma. Ann Nucl Med. 2004;18:291–296. doi: 10.1007/BF02984466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao Y, Sundgren PC, Tsien CI, et al. Physiologic and metabolic magnetic resonance imaging in gliomas. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1228–1235. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schlemmer HP, Bachert P, Herfarth KK, et al. Proton MR spectroscopic evaluation of suspicious brain lesions after stereotactic radiotherapy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1316–1324. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schlemmer HP, Bachert P, Henze M, et al. Differentiation of radiation necrosis from tumor progression using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Neuroradiology. 2002;44:216–222. doi: 10.1007/s002340100703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paulson ES, Schmainda KM. Comparison of dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced MR methods: recommendations for measuring relative cerebral blood volume in brain tumors. Radiology. 2008;249:601–613. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2492071659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]