Abstract

Sciatica-like leg pain can be the main presenting symptom in patients with cervical cord compression. It is a false localizing presentation, which may lead to missed or delayed diagnosis, resulting in the wrong plan of management, especially in the presence of concurrent lumbar lesions. Medical history, physical findings and the results of imaging studies were reviewed in two cases of cervical cord compressions, which presented with sciatica-like leg pain. There was multi-level cervical spondylosis with cord compression in the first patient and the second patient had two levels of cervical disc herniation with cord compression. In both cases, there were co-existing lumbar lesions, which could be responsible for the presentation of the leg pain. Cervical blocks were diagnostic in identifying the level responsible for the leg pain and it was confirmed so after cervical decompressive surgery in both cases, which brought significant pain relief. Funicular leg pain is a rare presentation of cervical cord compression. It is a referred pain due to the irritation of the ascending spinothalamic tract. Cervical blocks were successful in identifying the cause of funicular pain in our cases and this may pave the way for further studies to establish the role of cervical blocks as a diagnostic tool for funicular pain caused by cord compression.

Keywords: Cord compression, Cervical blocks, False localizing signs, Sciatica, Tract pain, Funicular pain

Introduction

Leg pain or sciatica is a rare ‘false localizing’ presentation of cervical cord compression and there has been only a few cases described in literature [1–5]. The term sciatica has often been associated with disorders of the lumbar spine and pelvis, and we often tend to overlook other parts of the spine in the search for its cause. We report two cases of cervical cord compression, which presented with sciatica-like leg pain. Each case is unique and different from one another in their presentation and concurrent spinal lesions. We hope that the discussion of these cases and the accompanying literature review will make us more aware of this uncommon presentation of leg pain in cervical cord compression.

Case reports

Case 1

A 61-year-old man with diabetes mellitus presented with a 4-month history of right-sided leg pain. The leg pain originated from the buttock region and radiated to the whole thigh, leg and whole foot (both dorsal and plantar surfaces). It was described as being constantly throbbing in nature. Clinically, there was some atrophy of the musculature of the right upper and lower extremities. The right ankle and big toe dorsiflexion was weak with a Medical Research Council (MRC) Muscle Strength Scale of grade IV and III, respectively. There was no hyperreflexia or any abnormal gait. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed lateral recess stenosis of L4–5 (Fig. 1) and cord compression at C4–5 and C5–6 due to cervical spondylosis (Fig. 2a). Electrophysiological studies showed right-sided L5 radiculopathy. L5 nerve root block was performed but it failed to relieve his leg pain; however, a subsequent C5–6 interlaminar epidural block completely relieved the symptom (Fig. 3). He underwent multilevel oblique corpectomy (MOC) of C4–6 and post-operatively there was significant improvement of his right leg pain score (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 1.

Right-sided lateral recess stenosis of L4–5

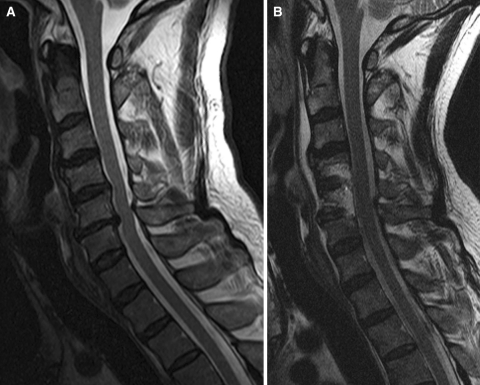

Fig. 2.

T2-weighted MRI scans of cervical spine showing pre-operative images of cord compression at C4–5 and C5–6 (a) compared with post-operative images (b)

Fig. 3.

Cervical interlaminar epidural block showing the extension of the contrast media at C5–6

Case 2

A 72-year old lady presented with a 1-year duration of constant right-sided leg pain. The leg pain was described as being ‘cold’ with tightness and was ascending in nature from the foot to the buttock. There was no significant neurological finding. She has had a previous history of decompression and instrumented fusion for L2–5 lumbar stenosis and decompressive laminectomy for tumor of the posterior element of C5–7 at another hospital in 2007. Radiological investigations did not reveal any malpositioned lumbar pedicle screws, but there was bilateral L5–S1 foraminal stenosis (Fig. 4). There were also disc protrusions, compressing the cord at C3–4 and C4–5, and the cervical cord was also bent posteriorly at the previous C6–7 laminectomy site (Fig. 5). She underwent decompression of the right L5–S1 foramen in 2009, but it only improved her leg pain by 30%. A selective C4–5 nerve root block [6] (Fig. 6) gave immediate relief of her leg pain and, subsequently, she underwent a C3–4 and C4–5 laminectomy. Post-operatively, her ascending leg pain was completely resolved, but only the ‘cold’ feeling of the limb remained.

Fig. 4.

Decompressive laminectomy and instrumentation from L2–L5 with foraminal stenosis at the L5–S1 level

Fig. 5.

T2-weighted MRI scan showing cervical cord compression at C3–4 and C4–5 with bending of the cord posteriorly at C6–7

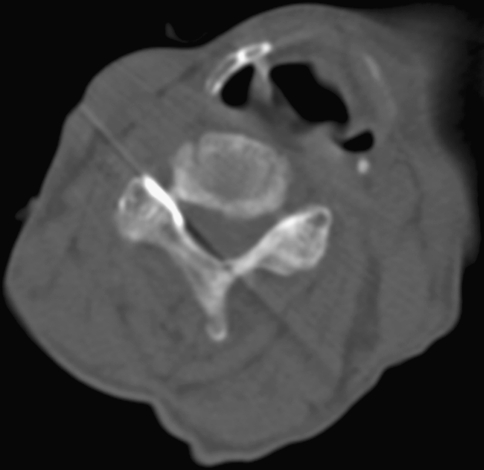

Fig. 6.

Selective C4–5 nerve root block with epidural extension of the contrast media on CT images

Discussions

In case 1, the patient was a diabetic who had a concurrent lumbar stenosis at L4–5. Apart from atrophy of the right upper extremity, he had no myelopathic signs to suggest cervical cord compression. His reflexes were not brisk and his leg pain, right ankle and big toe weakness could have been due to the lumbar stenosis. It was the right upper extremity atrophy that alerted us to the possibility of cervical cord involvement. Rhee et al. [7] have reported that 21% of cervical myelopathic patients fail to demonstrate any myelopathic signs, and the presence of any co-existing diabetes and root compression at the lumbar spine could further dampen any myelopathic sign presentation. Hand and forearm muscle atrophy due to cervical cord compression has been termed as cervical spondylotic amyotrophy and has been described by various authors [8, 9]. Though the exact pathophysiology of this syndrome is poorly understood, Taylor et al. [10] attributed this phenomenon to anterior horn cell damage caused by venous distension and stagnant hypoxia. The diagnostic cervical epidural block was effective in confirming the cause of the leg pain, especially in the presence of co-existing lumbar spinal stenotic lesion at L4–5.

Case 2 also presented with leg pain, but the previous history of C5–7 and L2–5 decompressive surgery together with the residual L5–S1 foraminal stenosis and posterior bending of the cervical cord at the C6–7 segment complicated the presentation. The leg pain, which was ascending from the foot to the buttock, was mistakenly interpreted as L5 radiculopathy and hence the L5–S1 surgery failed to relieve it completely. This pain could also have been contributed by the posterior bending of the cervical cord at C6–7 or cord compression at C3–4 and C4–5. The selective C4–5 nerve root block was diagnostic in determining the source of pain.

These two cases have several things in common: cervical cord compression, pre-existing or previous spinal lesions, sciatica-like leg pain, and successful cervical epidural blocks in identifying the responsible levels and confirmed so with decompressive surgery. The leg pain presentation is atypical of cervical cord compression and does not conform to the traditional clinicoanatomical correlation on which our neurological examination was based on [11]. The leg pain presentation is considered ‘false localizing’ of the cervical cord compression, as there are discrepancies between the neurological signs and the expected anatomical locus of the lesion. The term “false localizing signs” was first described by James Collier [12] in 1904 after finding discrepancies between antemortem clinical features with expected postmortem anatomical findings of 161 cases of intracranial tumors.

Spinal cord compression occasionally causes pain that is referred to the lower back or lower extremities, which is well below the level of the lesion. Such pain is called “tract or funicular pain” and there have only been a few cases described in literature [1–5]. Langfitt et al. [3] described three patients with cervical cord compression who presented with leg pain only and no other neurological signs to suggest spinal cord compression. Ito et al. [1] also presented two cases of sciatica caused by cervical and thoracic cord compression and Neo et al. [5] described popliteal leg pain due to cervical disc herniation. In all of these cases, the leg pain resolved after cervical cord decompression.

Some authors have attempted to characterize the clinical symptoms of funicular pain (which is a type of sclerotomal pain) to facilitate its diagnosis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of the characteristics of funicular pain with radicular pain

| Funicular pain | Radicular pain |

|---|---|

| Continuous or constantly present [3, 13] | Exacerbated by stretching of root |

| Diffuse and poorly localized [2, 3] | Excellent localization |

| Symmetrical and non-dermatomal [2, 3] | Along dermatome |

| Deep [3] | Superficial |

| ‘Hot’ or ‘cold’, burning, boring, aching and superimposed sharp sensations [3] | Sharp, stabbing |

| Contralateral to cord compression [3, 4] | Same side as root compression |

| Intense, does not correlate with physical findings [5] | Correlates with physical findings |

The clinical presentations of our cases were consistent with some of the clinical features suggested by various authors. The leg pain in case 1 had a diffuse picture, constant, burning, non-dermatomal and involved the whole right lower extremity. In case 2, the leg pain was described as ‘cold’ with tightness and was in an ascending manner instead of the classical descending radicular pain pattern.

Neo et al. [5] have suggested that there was yet no conclusive diagnostic key and the only confirmation of tract pain was pain relief after surgery. However, in both our cases, cervical epidural blocks were successful in determining the level responsible for these atypical leg pains. Though the cervical block methods used in these two cases were different, cervical nerve root block is associated with epidural extension of the injectorate [6] and it was this epidural extension of the steroid, which might be responsible for the pain relief instead of the nerve root block per se (Fig. 6). Hence, it was the cervical epidural steroid block, given either in a foraminal or interlaminar approach, which was helpful to differentiate the compressive cervical lesions as the cause of the leg pain from that of any lumbar stenotic lesions.

Funicular pain is commonly associated with intramedullary spinal tumors and spinal cord injury. It is an uncommon presentation of epidural cord compression due to extramedullary spinal cord tumor and is a rare presentation of cord compression by cervical spondylosis [14].

The exact pathomechanism of funicular pain is yet unclear. There are two postulated mechansims (Table 2).

Table 2.

Postulated mechanism of funicular pain

| Postulated mechanisms | Pathomechanism | Clinical examples of the postulated mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Irritation of the ascending spinothalamic tracts [1, 2, 4] | 1. Mechanical deformation of the ascending tract caused by the stenotic spine [15] | The L-hermitte sign is a type of funicular pain |

| 2. Increased mechanosensitivity of damaged axons due to demyelination of the ascending tracts [14] | ||

| Interruption of the pathways of pain modulation | 1. Disinhibition of the ascending pain-producing pathways that normally inhibit pain signals, thereby permitting the brain to interpret the absence of normal inhibition as pain [16] | Pain drawings of patients with cervical cord compression showed significant amount of pain in the territories well below the level of cord compression (thoracic, low back and leg pain) [17] |

| 2. Interruptions of the descending antinociceptive projections from the rostral ventral medulla (RVM), which plays a critical role in the modulation and maintenance of pain threshold [17] |

The clinical significance of tract pain is that it may pose diagnostic problems, especially in patients who have pain alone, without any other neurological symptoms, or in those who have concurrent lumbar spinal lesions. The incorrect interpretation of the source of this pain may mislead us into examining the wrong part of the spine without any significant findings, thus leading to a missed or delayed diagnosis, or perform unnecessary surgery over presumed responsible lesions in the spine without any alleviation of the symptoms. Hence, cases which present with sciatica-like leg pain, but in a non-radicular classical pattern, should always alert a suspicion to a possible cause of cord compression at a higher level. This case report also highlighted the success of cervical epidural blocks in identifying the cause of pain in both our cases and this may pave the way for further studies to explore cervical epidural blocks as diagnostic tool for identifying funicular leg pain caused by cord compression.

Conclusions

Sciatica-like leg pain is a rare presentation of cervical cord compression. This referred pain is known as funicular pain and is due to irritation of the ascending spinothalamic tract. Cervical epidural blocks were successful in identifying the cause of funicular pain in our cases and this may pave the way for further studies to establish the role of cervical epidural blocks as a diagnostic tool for funicular pain caused by cord compression.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank In-Sook Cho, B.A., for the editorial assistance. This paper was partly funded by research grants from Wooridul Spine Hospital Foundation.

Conflict of interest None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ito T, Homma T, Uchiyama S. Sciatica caused by cervical and thoracic spinal cord compression. Spine. 1999;24:1265–1267. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199906150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kobayashi S. “Tract pain syndrome” associated with chronic cervical disc herniation. Hawaii Med J. 1974;33:376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langfitt TW, Elliott FA. Pain in the back and legs caused by cervical spinal cord compression. JAMA. 1967;200:382–385. doi: 10.1001/jama.200.5.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott M. Lower extremity pain simulating sciatica: tumors of the high thoracic and cervical cord as causes. JAMA. 1956;160:528–534. doi: 10.1001/jama.1956.02960420008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neo M, Ido K, Sakamoto T, Matsushita M, Nakamura T. Cervical disc herniation causing localized ipsilateral popliteal pain. J Orthop Sci. 2002;7:147–150. doi: 10.1007/s776-002-8437-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner A. CT fluoroscopic-guided cervical nerve root blocks. Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhee JM, Heflin JA, Hamasaki T, Freedman B. Prevalence of physical signs in cervical myelopathy: a prospective, controlled study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:890–895. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31819c944b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebara S, Yonenobu K, Fujiwara K, Yamashita K, Ono K. Myelopathy hand characterized by muscle wasting. A different type of myelopathy hand in patients with cervical spondylosis. Spine. 1988;13:785. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198807000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathews J. Wasting of the small hand muscles in upper and mid-cervical cord lesions. QJM. 1998;91:691. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/91.10.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor AR, Byrnes DP. Foramen magnum and high cervical cord compression. Brain. 1974;97:473–480. doi: 10.1093/brain/97.1.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larner AJ. False localising signs. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:415–418. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.4.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collier J. The false localizing signs of intracranial tumour. Brain. 1904;27:490–508. doi: 10.1093/brain/27.4.490. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawakita E, Kasai Y, Uchida A. Low back pain and cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2009;17:187–189. doi: 10.1177/230949900901700213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byrne T, Waxman S, Benzel E. Clinical pathophysiology of spinal signs and symptoms. In: Byrne T, Waxman S, Benzel E, editors. Diseases of the spine and spinal cord. USA: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 40–90. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shenkin H, Alpers B. Clinical and pathologic features of gliomas of the spinal cord. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1944;52:87. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mignucci L, Bell G. Differential diagnosis of sciatica. In: Rothman R, Simeon F, editors. The spine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1992. pp. 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thimineur M, Kitaj M, Kravitz E, Kalizewski T, Sood P. Functional abnormalities of the cervical cord and lower medulla and their effect on pain: observations in chronic pain patients with incidental mild Chiari I malformation and moderate to severe cervical cord compression. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:171. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200205000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]