Abstract

Epithelioid sarcoma (ES) is a rare type of soft tissue tumor. The common location of ES is at the extremities and rarely occurs in axial skeleton. Only two cases have been reported so far. Initial wide resection is recommended for the treatment of ES. However, the local recurrent rate is high and repeat surgical resection is still an option for the treatment of the recurrent. In the spine, however, the proper treatment of recurrent ES has not yet been published. Therefore, the objective of this case report is to illustrate the management strategies for the local recurrent ES after initial surgical resection in the thoracic spine. A 14-year-old boy was diagnosed for ES in the thoracic spine for 2 years. He was first treated by surgical resection followed by the chemotherapy and radiotherapy but the disease had progressed and the spine was gradually deformed. He was admitted to our facility with a large soft tissue mass, severe kyphotic deformity and neurological deficit. We removed the tumor en bloc by one-stage posterior only approach. The posterior transpedicular spinal instrumentation and fibular strut graft were used for the reconstruction. On the last follow-up, 2 year after the surgery, the patient remained in good condition. In conclusion, the recurrent ES of the spine can still archive a good oncological outcome with repeat radical resection, but the initial radical resection remains the best treatment option in order to retard the relentless course of this kind of malignancy.

Keywords: Epithelioid sarcoma, Recurrent, Thoracic spine, En bloc spondylectomy

Introduction

Epithelioid sarcoma is a rare type of soft tissue tumor, accounting for less than 1% of all soft tissue sarcoma [1, 2]. Histologically, epithelioid sarcoma composes of large polygonal cells often associated with lymphocytic infiltration and central necrosis, which can mimic benign granulomatous lesion such as tuberculosis. This tumor is usually slow growing with a seemingly benign pathomorphologic appearance and often misdiagnosed on the first encounter [3]. The common location of epithelioid sarcoma is at the extremities with varying incidence in the trunk and rarely occurs in axial skeletal [4–6]. To our knowledge, there are only two cases reported in the spine, lumbosacral junction [7] and thoracic spine [6].

The most widely recommended treatment for epithelioid sarcoma is an initial wide resection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy. However, the local recurrent rate is high with likelihood for metastasis [5, 8]. The repeat surgical resection is still an option for the treatment of the recurrent epithelioid sarcoma as described in literatures [8, 9]. However, to date, there has been no report about the treatment of the recurrent epithelioid sarcoma in the spine. Therefore, the objective of this case report is to highlight the unique location of the epithelioid sarcoma and to illustrate the management strategies for the local recurrence after initial surgical resection in the thoracic spine.

Case report

A 14-year-old boy was referred to our clinic from a pediatric hospital. He had been suffering from back pain since he was 8 years old. The first physician found the osteolytic lesion at L2, and the first impression was tuberculous spondylitis. Thus, the medical treatment for tuberculosis was administrated. However, the disease process was progressive, so the biopsy was then performed and epithelioid sarcoma was diagnosed. He underwent surgical resection and spinal reconstruction by spinal implants followed by chemotherapy and radiotherapy. He was followed up for 2 years, but unfortunately the disease was progressing, and the spinal column was gradually deformed. He could not sit up-right because of the severe debilitating pain, so he was referred to our clinic for further evaluation and management.

Our evaluation revealed that he had severe back pain, deformity and sensory disturbances of both lower extremities. The examination showed severe kyphotic deformity on the thoracolumbar region with firm consistency mass measuring 15 cm fixed to the surrounding structure. Unfortunately, complete motor deficit with no sacral sparing was detected on the neurological examination. The sensory deficit was detected below T10 spinal level. Plain X-ray revealed severe kyphotic deformity at thoraco-lumbar region measuring 62° by means of Cobb method. The spinal column was totally disrupted and spinal implant construct was totally dislodged from the spine including the interbody mesh. Furthermore, osteolytic lesions of the posterior element were detected from T11 down to L4 level (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance image (MRI) showed inhomogeneous enhancing soft tissue tumor occupying posterior element and expanding to the surrounding muscle extending from T11 down to L4 level measuring 145 mm in length. The tumor had invaded into the extradural space and compressed the dural sac from the posterior at level of T11–T12. The tumor infiltration was demonstrated in the T12, L1, L3 and L4 vertebral bodies. Moreover, because of the disruption of the spinal column and posterior displacement of L1, the dural sac was also compressed by the posterior-inferior corner of L1 vertebral body and caused myelomalacia of the spinal cord (Figs. 2, 3). Subsequent angiogram demonstrated high vascularity of the tumor. Moreover, the right lower lung mass was detected by positron emission tomography (PET) scan during the tumor staging protocol (Fig. 4).

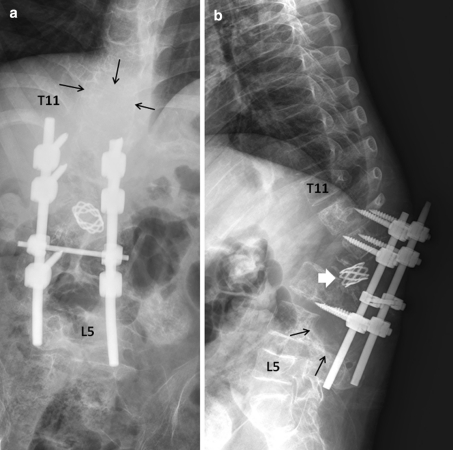

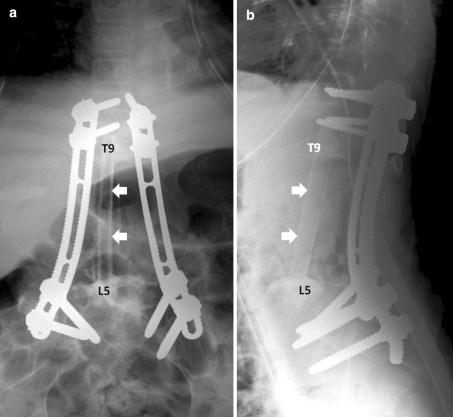

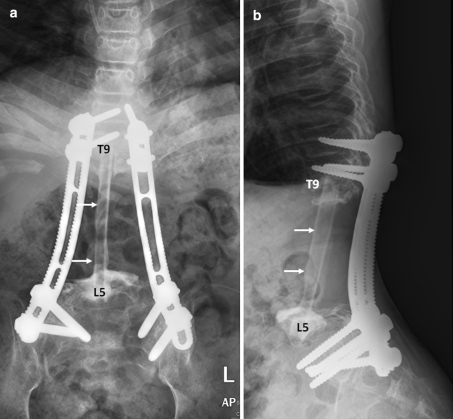

Fig. 1.

Plain radiographs of the thoracolumbar spine in AP (a) and lateral (b) views revealed severe kyphotic deformity of the thoracolumbar junction. The spinal column was totally disrupted and the spinal implant construct was totally dislodged from the spine including the interbody mesh (thick white arrow in b). The osteolytic lesions involving posterior elements were detected from T11 down to L4, with destruction of the vertebral bodies from T12 down to L4 (black arrows in a and b)

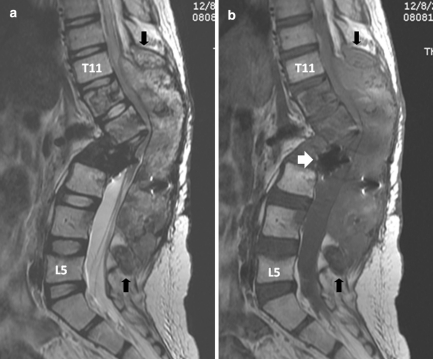

Fig. 2.

Sagittal T2-weighted (a) and corresponding T1-weighted (b) MR images revealed a huge inhomogeneous intensity mass involving posterior elements of T11 down to L4 (between black arrows), and the vertebral bodies of T12 down to L4 resulting in long-segment spinal cord compression. The dislodged interbody mesh was identified (thick white arrowb)

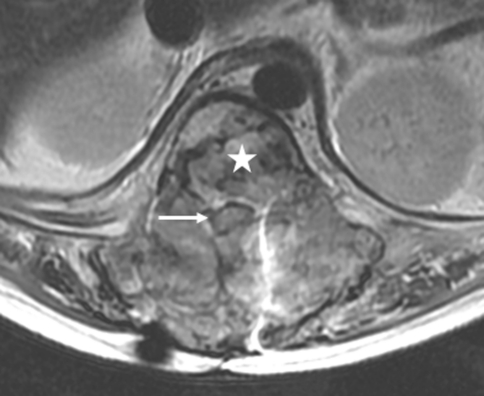

Fig. 3.

Axial T2-weighted MR image through the T12 level revealed that the tumor infiltrates the extradural space in all directions, compressing the spinal cord (arrow) causing myelopathy, and involving the T12 vertebral body (star)

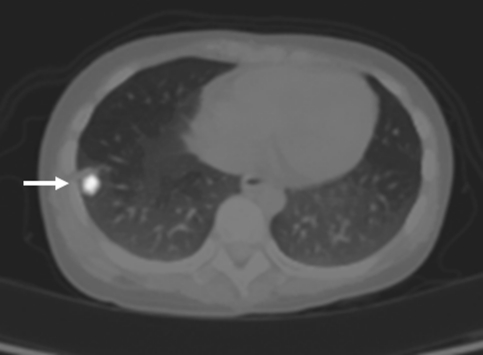

Fig. 4.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan revealed increased uptake in the right lung periphery, and proved to be pulmonary nodule in PET-CT fused image, highly suggestive of pulmonary metastasis (white arrow)

After successful preoperative embolization, total en bloc tumor resection and spondylectomy was performed by one-stage posterior only approach. The upper resection margin was T11 and the lower end resection margin was L4 vertebral body where the tumor was not involved. The midline incision was made over the involved vertebral segment and the tumor mass and then, with careful dissection, the spinous process of T10 in the cranial and L4 in the caudal part of the tumor mass were identified. The lateral dissection was carried out to expose the lamina of the T10 and L4 accordingly. After successful exposure, T10 and L4 total laminectomy was done and the dural sac was then identified and resected, in addition, the running closure of the dura sac stump was performed to prevent leakage of cerebrospinal fluid. Then, with careful dissection, the tumor mass infiltrating into the paravertebral muscles was exposed, until it reached the lateral border, with the great care for any injury of tumor capsule envelope in which the en bloc resection could be accomplished. After the lateral border of the mass had been identified, gentle blunt dissection was applied to anterior vertebral bodies and then the great vessels were pulled away, very carefully, to avoid the damage while removing the involved vertebrae. The upper and lower vertebral bodies were then resected though the vertebral body. No attempt was made to remove the spinal implants because they were concealed by the tumor. Alternatively, they were removed en bloc within the mass. The fibular strut graft was used for the anterior supporting structure. Posterior transpedicular instrumentation from T7 to S1 was carried out (Fig. 5). The intra-operative blood loss was 3,000 cc. After the surgery, the patient was put on the rigid brace, for 6 months, in anticipation for the healing of interbody strut graft. The pathological diagnosis was epithelioid sarcoma. The margins of the resection were free of tumor. Immunohistochemical study demonstrated positive for cytokeratin, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and vimentin and negative for CD31 (Figs. 6, 7). Although, there was no established progression of the residual lung mass but the new consolidation was detected at the left lower lung (Fig. 8). However, no residual tumor was detected on subsequence MRI 2 years after the operation. The pain was significantly decreased and no recurrent tumor was detected at the last followup 26 months after the surgery. The spinal reconstruction was remained properly, no implant breakage was observed and the cortical thickness of the fibular strut graft was established, however, the upper spinal column was slightly changed into kyphotic alignment (Figs. 9, 10).

Fig. 5.

Plain radiographs in AP (a) and lateral (b) views of the lumbar spine after en bloc tumor resection. The posterior pedicular screw plate system was used to reconstruct the spine. The fibular strut graft (white arrows) was used for anterior support

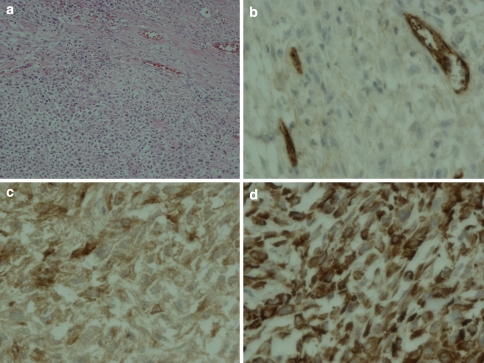

Fig. 6.

Histopathological features (magnification ×200) demonstrated epithelioid and spindle cells (a). Immunohistochemical study (magnification ×400) showed negative for CD 31 (b) but positive for EMA (epithelial membrane antigen) (c) and vimentin (d)

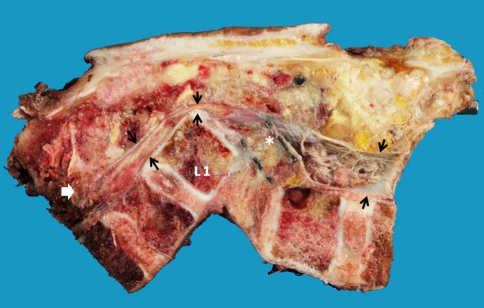

Fig. 7.

The pathological section after en bloc resection, showed the resection margin of the upper and lower vertebral bodies. The dural sac was outlined by the black arrow demonstrated the compression by the postero-inferior corner of L1 body and interbody mesh (asterisk). The epidural invasion of the tumor (white arrow) was completely resected

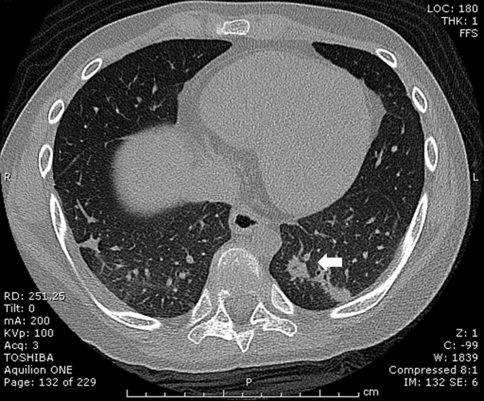

Fig. 8.

Computerized tomography (CT) scan at 26 months post-operative en bloc tumor resection revealed the new consolidation in the left lower lung (white arrow), the lesion remained stable after subsequence CT scan. The pulmonary nodule detected on the PET scan is not established

Fig. 9.

Plain radiographs in AP (a) and lateral (b) views of the lumbar spine after 26 months after en bloc tumor resection. The posterior pedicular screw plate construction was remained stable, however, the superior migration of the graft was detected and the upper spinal column was slightly changed into kyphotic alignment. The cortical remodeling of fibular strut graft (white arrows) was observed

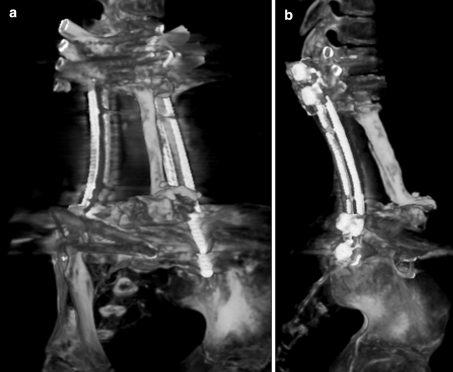

Fig. 10.

The CT-3D reconstruction of the spinal fixation and fibular bone graft constructed in oblique (a) and lateral (b) views showed the union of the fibular graft at the junctions and the remodeling pattern of the graft

Discussion

Epithelioid sarcoma (ES) is a rare soft tissue neoplasm, frequency occur in extremities and rarely in the trunk area [10–12]. Clinically, ES is usually present as painless, slow growing mass that mimics the benign process which causes a delay in establishing the diagnosis [1, 6]. ES is recognized as an aggressive neoplasm, consisting of solid multinodular mass, ill-defined border and diffusely infiltrative to the surrounding tissue. Histologically, ES is composed of polygonal or epithelioid cells embedded in the desmoplastic fibrous stroma. The tumor is often associated with lymphocytic infiltration and necrosis resulting in a pseudogranulomatous appearance, which can mimic benign granulomatous lesion. For the immunohistochemical features, ES demonstrates positive stain for cytokeratin and EMA in more than 90% of the cases. Vimentin is usually positive in most cases. The co-expression with EMA or cytokeratin has been reported. The CD 31 is usually negative [1]. In our specimen, the histomorphology was typical and immunohistochemical pattern supported the diagnosis.

In general, the prognosis of ES is poor and the local recurrent rate of ES is high. Many series have reported the recurrent rate ranging from 19–56% within 1 year [8, 10–12]. Factors that adversely affect the survival rate are as follow: the tumor size more than 5 cm, primary location of tumor in trunk area, the infiltration to surrounding structure, lymph node involvement and local recurrent [8, 11]. Wide surgical excision remains the best treatment for this tumor. Casanova et al. reported the higher disease free survival in an initial complete resection with histologically free surgical margin. The remaining tumor after surgical excision, even microscopically, was associated with the early local recurrence [11]. Radiotherapy should be considered in the patient in whom the complete resection was not accomplished, although the benefit to decrease the local recurrent was uncertain [10]. However, the repeat surgical excision is remaining an option in the recurrent cases [8, 13].

In the spine, however, the total eradication of the tumor by an en bloc excision is compromised by the presence of neural structures. Thus, the intralesional resection is the only option [6, 7]. In our case, the patient was first treated by an intralesional resection followed by chemotherapy and radiotherapy. However, the tumor recurred after 1 year of treatment. To eradicate the tumor and prevent the recurrence the total en bloc spondylectomy should be the best option, as described in previous literatures [14–16]. Unfortunately, in our case, the tumor was widespread, involving most of the vertebrae resulting in mal-alignment of the spinal column. It also expanded into the spinal canal and caused neurological compromise. Moreover, the tumor was located mainly in the dorsolateral aspect of the spinal column and additionally the numbers of pedicle were involved. Thus, it was unfeasible to achieve the extralesional resection margin without the necessity to sacrifice the spinal cord [15]. Therefore, in this case, to achieve the extralesional resection margin and prevent the tumor contamination, the spinal implants were necessary to be removed en bloc within the mass and the spinal cord needed to be sacrificed. In final pathological review, all the resection margins were free of tumor as a result the patient revealed the local recurrent free period of 26 months after the surgery. However, the pulmonary metastasis still remained the problem in this patient.

In conclusion, epithelioid sarcoma of the spine is an extremely rare entity and has high possibility of local recurrence. Though repeat radical resection can achieve a good oncological outcome in the case of recurrence, the initial radical resection remains the best treatment option in order to retard the relentless course of this kind of malignancy.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Armah HB, Parwani AV. Epitheloioid Sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:814–819. doi: 10.5858/133.5.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher C. Epithelioid sarcoma of Enzinger. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13(3):114–121. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200605000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chase DR, Enzinger FM. Epithelioid sarcoma: diagnosis, prognostic, indicators, and treatment. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:241–263. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198504000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guillou L, Wadden C, Coindre JM, Krausz T, Fletcher CD. “Proximal-type” epithelioid sarcoma, a distinctive aggressive neoplasm showing rhabdoid features: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study of a series. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:130–146. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199702000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross HM, Lewis JJ, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Epithelioid sarcoma: clinical behavior and prognostic factors of survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 1997;4(6):491–495. doi: 10.1007/BF02303673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weisskopf M, MÜnker R, Hermanns-Sachweh B, Ohnsorge JAK, Siebert C. Epithelioid sarcoma in the thoracic spine. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:s604–s609. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0061-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steib JP, Pierchon F, Farcy JP, Lang G, Christmann D, Gnassia JP. Epithelioid sarcoma of the spine: a case report. Spine. 1996;21:634–638. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199603010-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Visscher SA, Ginkel RJ, Wobbes T, Veth RP, Ten Heuvel SE, Suurmeijer AJ, Hoekstra HJ. Epithelioid sarcoma: Still an only surgically curable disease. Cancer. 2006;107(3):606–612. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evan HL, Baer SC. Epithelioid sarcoma: a clinicopathologic and prognostic study of 26 cases. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1993;10(4):286–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baratti D, Pennacchioli E, Casali PG, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: prognostic factors and survival in a series of patients treated at a single institution. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(12):3542–3551. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9628-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casanova M, Ferrari A, Collini P, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma in children and adolescents: a report from the Italian Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee. Cancer. 2006;106(3):708–717. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chbani L, Guillou L, Terrier P, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 106 cases from the French sarcoma group. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131(2):222–227. doi: 10.1309/AJCPU98ABIPVJAIV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minamida S, Irie A, Ishii J, Minei S, Takashima R, Kadowaki K, Morinaga S, Iwamura M. Case of local recurrent of the periurethral proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma successful treated by repeated regional excision. Hinyokoka Kiyo. 2007;53(10):733–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao G, Suki D, Chakrabarti I, et al. Surgical management of primary and metastatic sarcoma of the mobile spine. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9:120–128. doi: 10.3171/SPI/2008/9/8/120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuda Y, Sakayama K, Sugawara Y, Miyawaki J, Kidani T, Miyazaki T, Tanji N, Yamamoto H. Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma treated with total en bloc spondylectomy for 2 continuous disease-free survival for more than 5 years. Spine. 2006;31(8):E231–E236. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000210297.02677.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samartzis D, Marco RAW, Benjamin R, Vaporciyan A, Rhines LD. Multilevel en bloc spondylectomy and chest wall excision via a simultaneous anterior and posterior approach for Ewing sarcoma. Spine. 2005;30(7):831–837. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000158226.49729.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]