Abstract

Background/purpose

Although rarely discussed in the literature and difficult to evaluate on plain radiographs, atlantooccipital osteoarthritis can be a source of persistent suboccipital pain. Our objective in this report is to describe two cases with atlantooccipital (O–C1) osteoarthritis treated with posterior occipitocervical fusion.

Methods and results

Two patients presented with unilateral suboccipital pain, which was refractory to conservative treatment. One patient suffered from long-standing rheumatoid arthritis while the other patient did not have pertinent medical issues. After non-diagnostic plain film imaging, CT scan demonstrated unilateral osteoarthritis of the atlantooccipital and atlantoaxial joint in both patients who subsequently underwent posterior O–C2 fusion with resolution of their preoperative symptoms.

Conclusions

This is, to our knowledge, the first case report which specifically focused on surgical treatment of atlantooccipital osteoarthritis. Occipitocervical fusion is a treatment option for patients with atlantooccipital osteoarthritis when suboccipital pain is not responsive to conservative treatment.

Keywords: Atlantooccipital osteoarthritis, Suboccipital pain, Occipitocervical fusion

Introduction

Degenerative changes of the atlantooccipital joints may rarely be the cause of persistent pain and dysfunction but has been infrequently described. As part of a larger series of patients with degenerative cervical spondylosis, Grob [1] reported three patients with CT scan-proven osteoarthritis of atlantooccipital joint who underwent isolated posterior atlantooccipital fusion. Similarly, Wertheim and Bohlman [2] included one patient with atlantooccipital osteoarthritis and disabling pain in a series of patients who underwent occipitocervical fusion. Neither series provided specific clinical details about these patients.

Symptoms are nearly identical in patients with occipitocervical osteoarthritis and atlantoaxial osteoarthritis. Unilateral, constant suboccipital pain is exacerbated by flexion–extension or lateral bending. Establishing a diagnosis is difficult with routine cervical radiographs as the occipitocervical articulation is not easily visualized; computed tomographic (CT) scans should be used to identify suspected degenerative changes of the O–C1 joint [2].

This report details two cases performed by two different surgeons in which upper cervical spine osteoarthritis affected the O–C1 joint and was treated with fusion after failure of conservative treatment.

Case 1

A healthy 73-year-old female presented with progressive right suboccipital pain after 5 years of unsuccessful conservative therapy with a soft cervical collar and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) for presumed cervical spondylosis. Her pain, exacerbated with neck flexion–extension and rotation, limited activities of daily living and recreational activities. On physical examination, her neck motion was severely restricted with torticollis secondary to the pain but she had no focal neurologic deficits. Transoral radiographs demonstrated right-sided atlantoaxial osteoarthritis and CT scan revealed osteoarthritis of the right atlantooccipital joint (Fig. 1). The patient underwent posterior fusion surgery from occiput to C2. A posterior approach was used utilizing a Mayfield Skull Clamp (Integra, Plainfield, NJ), taking care to avoid vascular injury as preoperative CT angiogram (CTA) and magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) revealed a high-riding dominant right vertebral artery. A left-sided C2 pedicle screw was placed as was a right-sided C2 laminar screw due to the position of the right-sided vertebral artery [3]. Oasys plates (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI) were fixed to the occiput using three screws on each side before ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene tape was passed between the posterior arches of C1 and C2 and tied across the rods connecting the C2 screws to the occipital plate. Following decortication, autologous iliac bone grafting was performed. The patient was placed in a cervical collar for 6 weeks and had resolution of the suboccipital pain. Cervical spine radiographs 1 year after the surgery showed a solid fusion from occiput to C2 (Fig. 2a, b). The patient has completed 2-year follow-up and has continued to do well with no complaints referable to the cervical spine and no evidence of screw loosening on serial radiographs.

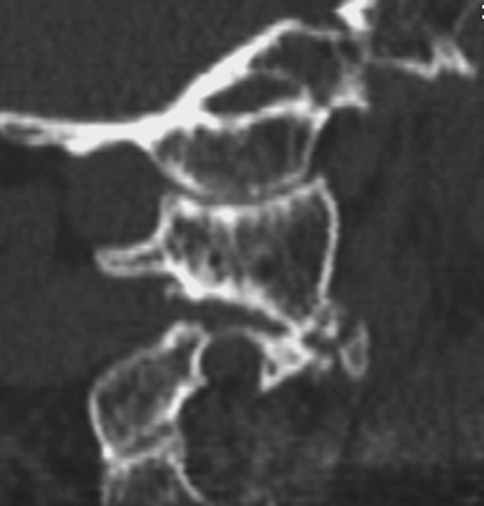

Fig. 1.

Case 1. Sagittal CT images demonstrate right atlantooccipital and atlantoaxial osteoarthritis

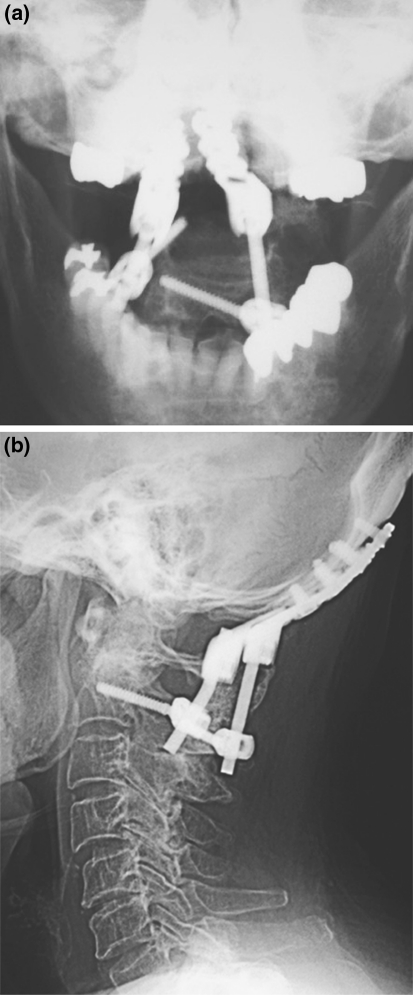

Fig. 2.

a, b Case 1. AP and lateral radiographs 1 year after surgery show solid fusion

Case 2

A 38-year-old female presented with 6 months of left suboccipital pain. The patient had a history of quiescent rheumatoid arthritis without cervical spine involvement. Treatment for her suboccipital pain included several months of physical therapy and trigger point injections without improvement. The patient could not turn her head and had difficulty sleeping because of the pain. Prior treatment using a soft collar provided some pain relief. On physical examination, her neck motion was severely restricted secondary to pain but she had no focal neurologic deficits. In addition to significant radiologic changes consistent with left atlantoaxial osteoarthritis visible on transoral views, CT scan showed left atlantooccipital osteoarthritis (Fig. 3). Of importance, given her history of rheumatoid arthritis, flexion–extension radiographs did not show the occipitocervical or atlantoaxial instability. The patient underwent posterior fusion surgery from occiput to C2 using occipital screws, C1 lateral mass screw [4, 5] and C2 pedicle screws with fluoroscopic guidance (Fig. 4). A Mountaineer occipital plate (Depuy Spine, Inc., Raynham, MA) was fixed to the occiput with screws and connected to cervical screws using bilateral rods before iliac crest bone grafting was performed. Postoperatively, the patient was maintained in a Miami-J collar for 6 weeks with complete resolution of her left suboccipital pain. Radiographs 6 months after surgery demonstrated solid fusion (Fig. 5).

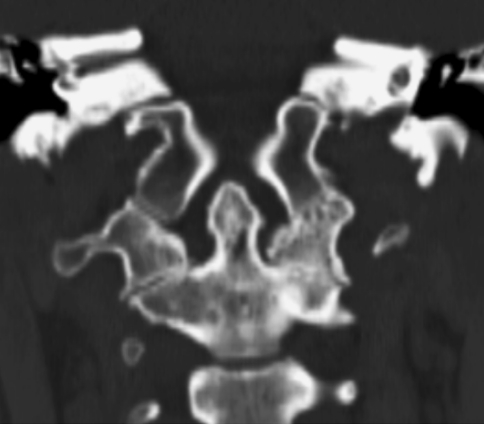

Fig. 3.

Case 2. Coronal CT images demonstrate left atlantooccipital and atlantoaxial osteoarthritis

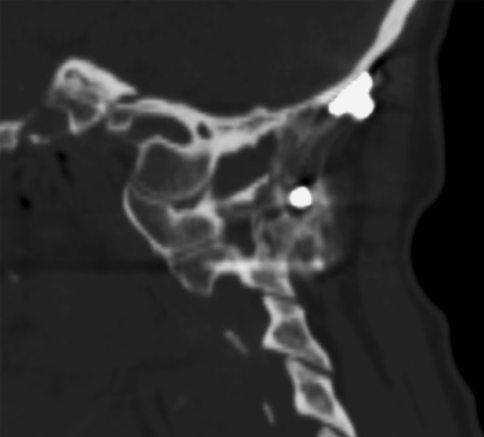

Fig. 4.

Case 2. Lateral radiograph after surgery

Fig. 5.

Case 2. Sagittal CT images demonstrate solid fusion

Discussion

Presenting symptoms of osteoarthritis of the atlantooccipital joint are similar to atlantoaxial segment symptoms; patients have unremitting unilateral suboccipital pain. Dreyfuss et al. [6]. reported that perceived pain was greater in intensity and distribution with provocative atlantooccipital joint injections in comparison to atlantoaxial joint injections. Atlantooccipital joint pain was primarily suboccipital, but reached as far anteriorly as the vertex. Laterally, the referral zone approaches but does not include the ear. Causes of O–C1 pain include degenerative, post-traumatic, post-infectious or rheumatoid arthritis, synovial joint adhesions and symptoms are often unilateral. Ultimately, cartilage destruction leads to chronic capsular irritation and inflammation with sensitivity to motions such as neck flexion–extension [7]. Atlantooccipital osteophyte formation rarely causes direct spinal cord compression because of a wide O–C1 canal. Headache is a common presenting complaint and may be aggravated by neck rotation and/or flexion–extension. Occipital headache is non-specific, however, and can arise from injuries affecting the C2–3 disc and facet joints, and the atlantoaxial or atlantooccipital joints but is not seen with lower cervical pathology unless triggered by muscle spasm [7]. Nausea, blurry vision, insomnia and tinnitus have been reported as presenting symptoms of atlantooccipital arthritis [7].

Plain radiographic diagnosis is difficult as the atlantooccipital joint is not well visualized with anteroposterior, lateral or open-mouth roentgenograms of the cervical spine. CT scan with coronal and sagittal reconstructions more clearly show O–C1 joint-space between the lateral mass of the atlas and the corresponding occipital joint surface. Joint-space reduction, subchondral sclerosis, osteophyte formation or cyst formation may be seen. Bone scan may also be utilized, demonstrating increased uptake [8]. Ogoke et al. [7] reported that imaging studies may often fail to diagnose this entity and stressed the importance of the history and physical examination. Both cases presented in this report, however, had clear evidence of osteoarthritic changes of the atlantooccipital and atlantoaxial joints.

It is essential to exclude other causes of upper cervical pain. Injury to suboccipital muscles, C1–C3 nerve roots, the C2–C3 disc, upper cervical ligaments, and upper cervical facet joints may produce suboccipital pain and headache [9–11]. Vertebral or basilar artery thrombosis, posteroinferior or anteroinferior cerebellar artery aneurysm, tension headaches, fibromyalgia, intracranial tumor, Arnold–Chiari malformation, Paget’s disease of the skull, and temporal arteritis may also mimic atlantooccipital joint pain [7].

Initial conservative treatment for O–C1 arthritis includes rest, soft cervical collars, NSAIDs, muscle relaxants and tricyclic antidepressants [7]. Physical therapy for gentle ROM exercises and other treatment modalities may be beneficial. Interventional procedures with O–C1 joint injections or nerve blocks may be both diagnostic and therapeutic [12]. Injections are reserved for patients with chronic symptoms and require experience and skill; reported complications have included seizure, spinal shock and hypotension [6, 7]. Patients with severe, intractable, suboccipital pain unresponsive to an adequate trial of non-operative treatment may be indicated for occipitocervical arthrodesis. Both cases described in this report had clear evidence of osteoarthritic changes at the atlantooccipital joint. Symptoms related to atlantooccipital arthritis may be non-specific, however, and difficult to differentiate clinically from pain related to C1–C2 degeneration. In the cases described in this report, fusion of both the O–C1 and C1–C2 motion segments was performed.

Modern modular screw-based constructs allow for rigid short-segment fixation [13, 14]. Uribe et al. [15] recently described the biomechanics of occipital condyle screw placement for occipitocervical fixation and emphasized that decreased construct lever arm, increased screw length, and use of the condyles as fixation points provides more rigid occipitocervical fixation without the need for increased rod diameter or multiple attachment points. This strategy retains the benefits of low profile modular craniocervical fixation while reducing complications associated with occipital screw placement. C1 fixation can be achieved via lateral mass screws [4, 5], ‘pedicle’ screws, wiring or use of ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene tape, which provides segmental stabilization similar to wiring [17]. C1 ‘pedicle’ screw fixation achieves strong purchase but requires preoperative CT angiogram to ensure the vertebral artery will not be endangered by screw placement and that the posterior arch is large enough to accommodate a screw [16]. C2 fixation is commonly achieved with pedicle screws or C1–C2 transarticular screws, both shown by Oda et al. [18] to provide high construct stiffness in comparison to sublaminar wiring and laminar hooks. Again, preoperative imaging is important to evaluate the C2 pedicle width and address concerns over location of the vertebral artery. Magnetic resonance angiogram can establish vertebral artery side dominance; a pedicle screw should not be placed in the scenario of a dominant, high-riding artery. This occurred in Case 1, so we elected to use laminar screw fixation, using the technique described by Wright [3]. Coronal and sagittal alignment at the time of fusion is important for head balance. Additionally, Yoshida et al. [19] reported upper-airway obstruction after short posterior occipitocervical fusion in a flexed position and Miyata et al. [20] reported that the O–C2 angle has considerable impact on dyspnea and/or dysphagia after O–C fusion.

Adult atlantooccipital motion is approximately 25° of flexion–extension, 5° of lateral bending, and 5° of rotation. Atlantoaxial motion is approximately 20° of flexion–extension, 5° of lateral bending, and 40° of rotation [21]. Fusion across these joints considerably limits cervical motion, particularly in flexion–extension and rotation. Patient education about limitations of postoperative cervical motion is critical, especially when occipitocervical fusion will include C2.

Occipitocervical osteoarthritis is a rare cause of suboccipital pain which is often difficult to diagnose but must be considered when a patient presents with persistent suboccipital pain as patients may require fusion when refractory to conservative treatment. The patients described in this report had resolution of their symptoms after successful occipitocervical fusion.

Key points

Two patients with chronic suboccipital pain had occipitocervical fusion surgery for atlantooccipital and atlantoaxial osteoarthritis.

Both patients had pain relief after surgery.

CT scan with sagittal and coronal reconstructions can effectively image the O–C1 facet joint.

Occipitocervical fusion may be considered for O–C1 osteoarthritis with consistent suboccipital pain which is refractory to conservative treatment but preoperative imaging to establish surgical risk to the vertebral artery is essential.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Grob D. Surgery in the degenerative cervical spine. Spine. 1998;23(24):2674–2683. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199812150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wertheim SB, Bohlman HH. Occipitocervical fusion. Indications, technique, and long-term results in thirteen patients. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1987;69(6):833–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright NM. Posterior C2 fixation using bilateral, crossing C2 laminar screws: case series and technical note. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2004;17:158–162. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200404000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goel A, Gupta S. Vertebral artery injury with transarticular screws. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:376–377. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.2.0376a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harms J, Melcher RP. Posterior C1–C2 fusion with polyaxial screw and rod fixation. Spine. 2001;26(22):2467–2471. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200111150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dreyfuss P, Michaelsen M, Fletcher D. Atlanto-occipital and lateral atlanto-axial joint pain patterns. Spine. 1994;19(10):1125–1131. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199405001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogoke B. The management of the atlanto-occipital and atlanto-axial joint pain. Pain Physician. 2000;3(3):289–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valdez DC, Johnson RG. Role of technetium-99m planar bone scanning in the evaluation of low back pain. Skeletal Radiol. 1994;23(2):91–97. doi: 10.1007/BF00563199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bogduk N. Cervical causes of headache and dizziness. In: Grieve GP, editor. Modern manual therapy of the vertebral column. London: Churchill Livingston; 1987. pp. 289–302. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bogduk N, Corrigan B, Kelly P, Schneider G, Farr R. Cervical headache. Med J Aust. 1985;143:202–207. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1985.tb122915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edmeads J. The cervical spine and headache. Neurology. 1988;38:1874–1878. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.12.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dreyfuss P, Roberts J, Dreyer S, et al. Atlanto-occipital joint pain: a report of three cases and description of an intra-articular joint block technique. Reg Anesth. 1994;19:344–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolfla CE. Anatomical, biomechanical, and practical considerations in posterior occipitocervical instrumentation. Spine J. 2006;6(6 Suppl):225S–232S. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finn MA, Bishop FS, Dailey AT. Surgical treatment of occipitocervical instability. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(5):961–968. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000312706.47944.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uribe JS, Ramos E, Vale F. Feasibility of occipital condyle screw placement for occipitocervical fixation: a cadaveric study and description of a novel technique. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21(8):540–546. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31816d655e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeom JS, Buchowski JM, Park KW, Chang BS, Lee CK, Riew KD. Undetected vertebral artery groove and foramen violations during C1 lateral mass and C2 pedicle screw placement. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33(25):E942–E949. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181870441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takahata M, Ito M, Abumi K, Kotani Y, Sudo H, Ohshima S, Minami A. Comparison of novel ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene tape versus conventional metal wire for sublaminar segmental fixation in the treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20(6):449–455. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e318030d30e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oda I, Abumi K, Sell LC, Haggerty CJ, Cunningham BW, McAfee PC. Biomechanical evaluation of five different occipito-atlanto-axial fixation techniques. Spine. 1999;24(22):2377–2382. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199911150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshida M, Neo M, Fujibayashi S, Nakamura T. Upper-airway obstruction after short posterior occipitocervical fusion in a flexed position. Spine. 2007;32(8):E267–E270. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000259977.69726.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyata M, Neo M, Fujibayashi S, Ito H, Takemoto M, Nakamura T. O–C2 angle as a predictor of dyspnea and/or dysphagia after occipitocervical fusion. Spine. 2009;34(2):184–188. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818ff64e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White AA, 3rd, Panjabi MM. The clinical biomechanics of the occipitoatlantoaxial complex. Orthop Clin North Am. 1978;9(4):867–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]