Abstract

Spine tumors are fairly common and the management is through a multimodality approach. Lesions of the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae have been treated with such extensive anterior and/or posterior approaches. The authors present a case of a 56-year-old lady with solitary T11 metastases from colonic carcinoma and a case of a 43-year-old lady with T5–T6 high-grade osteogenic sarcoma. The treatment consists of a wide vertebrectomy by posterior approach, after anterior release and sub-pleural dissection using a thoracoscopic approach. A thoracoscopic assisted anterior approach could reduce the duration and the morbidity of a vertebrectomy without affecting oncological management.

Keywords: En bloc resection, Metastases, Spine tumor, Thoracoscopy, Vertebrectomy

Introduction

En bloc resection of bone tumors occurring in the vertebral body has been well described in multiple papers encompassed by titles such as vertebrectomy [1] or spondylectomy [2].

The described surgical techniques are based on either a single posterior approach or on a combination of posterior and anterior approaches [3]. The posterior techniques have the advantage of a shorter operative time. The combined allows the resection of the anterior structures under direct visual control, and seems safer with regard to any injury of the major and minor blood vessels. This method is also better in terms of the oncological management as a layer of healthy tissue can be left over any anterior tumor growth as a margin. Thoracoscopic assisted surgical techniques have become sophisticated and used for wider indications [4, 5]. A thoracoscopic assisted anterior approach could reduce the duration and the morbidity of a vertebrectomy without affecting oncological management.

Case 1

A 56-year-old lady with a history of a colonic carcinoma, had undergone a hemicolectomy 9 years previously. Although initial staging studies were negative, at 6 years from the original diagnosis of the primary, the patient had new symptoms of back pain. A solitary T11 lesion was identified on the various imaging studies. The lesion was radiated and closely followed by the primary oncology team. Due to progressively worsening back pain the patient was referred to our institution for spine oncology care. New staging studies revealed three small lung nodules and a solitary bone lesion in T11 (Fig. 1a). Based on the current findings, the oncology plan of action was to resect the symptomatic vertebral lesion and at a later stage, resection of the non-progressive lung nodules.

Fig. 1.

Axial CT showing the extension of the tumor into the right posterior elements, and relative sparing of the left side

The patient had preoperative embolization of the T11 segmental arteries, performed in the radiology suite the day prior to the surgery. Anterior release with adequate surgical margins of the involved segment was obtained by thoracoscopic approach. Next step was posterior T11 resection and spinal stabilization from T8 to L2. Postoperatively, the patient only spent one night in the intensive care unit, and was stable to be transferred to the regular ward. The pain was also notably less, as only one day of intravenous narcotics were used, followed by oral narcotic analgesics; ambulation began after 4 days.

Patient was discharged after a total of 10 days in the hospital.

The patient is continuously disease free at 30 months after tumor resection.

Case 2

A 43-year-old woman with recent history of back pain on conventional radiology showed an osteogenic lesion of vertebra T6 invading vertebral body and the right costovertebral angle of T5, further imaging studies confirmed the absence of distant secondary lesions. CT-guided needle biopsy was performed elsewhere and histological diagnosis of osteoblastic chondrosarcoma was confirmed at our institution. T4–T7 en bloc resection was performed through a combination of thoracoscopic and posterior approaches. Stabilization was achieved by a posterior T2–T10 instrumentation. Histological exam of the specimen revealed a high-grade osteosarcoma. She received adjuvant chemotherapy according with current protocols. No complications were observed in early post-op. The patient was allowed to walk on 6 days. The patient is continuously disease free at 24 months after tumor resection without complication.

Description of the procedure

Following induction of anesthesia with the placement of a double lumen intubation tube, the patient is laid in lateral position. The involved vertebra is identified on fluoroscopy and the skin marked with the borders of the vertebra. Three portals are made in the intercostal spaces along the anterior axillary fold which would give good access to the involved vertebra. Following the deflation of the lung and the introduction of the thoracoscopy instruments, the involved vertebra is once again identified under fluoroscopy and the segmental artery identified. This is carefully dissected and transected after application of vascular clips. A patch of pleura is left on the vertebra as a tumor free margin (Fig. 2). Sub-pleural dissection is then carried more anteriorly and also towards the opposite side of the tumor, as far as can be done safely. The instruments are removed, the wounds closed and the lung is reinflated.

Fig. 2.

Thoracoscopic view of the pleura that had been dissected around the T11 to be left as a patch of margin for the resection

After placing the patient in a prone position, a posterior approach to the lesion follows. Laminectomies are carried out, nerve roots affected by tumor are ligated and transected. The left segmental artery was ligated and transected. Pedicle screws are placed at least two levels above and below the involved segment, and a single rod is applied on one side to stabilize the spine prior to removal the spinal segment posteriorly from the opposite side. Osteotomies of bodies at appropriate level is carried out using a Gigli saw, and after releasing any small fibrous bands between the posterior longitudinal ligament and the dura, the resected vertebral mass is removed (Figs. 3, 4).

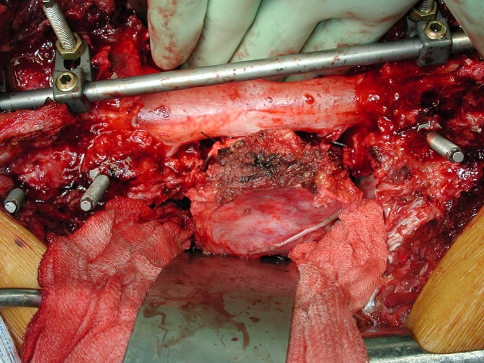

Fig. 3.

The spinal cord within the dura is visible, and the resected vertebra is carefully manipulated around the cord for removal. A single posterior rod is applied to the opposite side (left) to stabilize the spine during the vertebral removal

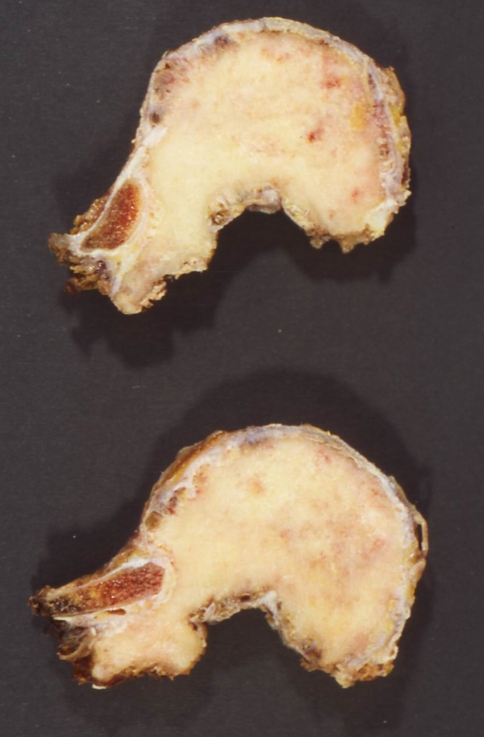

Fig. 4.

Gross pathology of the resected vertebra

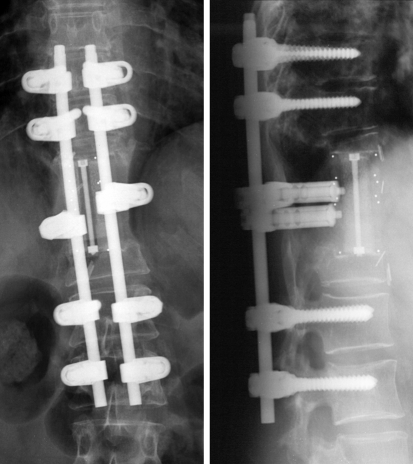

A carbon cage is used for reconstruction and the posterior instrumentation is completed (Fig. 5). Since a patch of the pleura has been resected as a margin, a Gore-tex mesh patch is sutured to this area.

Fig. 5.

Postoperative X-ray

In both patients the anterior procedure had minimal blood loss, and the amount lost from the posterior approach was comparable to a standard posterior approach fusion surgery. There was no change in the total operative time, but this could be shortened as the experience in the thoracoscopy improves, as this was the initial approach with thoracoscopy at the institution.

Discussion

A more aggressive approach has been taken by the oncologists and surgeons managing patients with spine metastases, and especially for solitary metastases has shown a favorable outcome [6]. These are due to improvement in the pain, maintenance of function, decrease in the recurrence and potential for improvement in the neurological status [7]. A complete wide resection of the vertebral lesion is not possible due to spinal canal and its contents, although if the tumor was localized to the body or the anterior elements, such a resection can achieve a negative margin [1, 8]. As such, and in cases of metastases, an attempt at the en bloc vertebrectomy can be achieved with regard to the body if adequate exposure can be ensured. Open thoracic approach for vertebrectomy will give an extensive exposure for the resection, but also has the risk for longer surgery, more blood loss and longer recovery with or without complications [7]. Although this approach may be advantageous for multi-level involvement, other approaches have been considered for a single level. An alternate approach would be to do an anterior and subsequently a posterior approach for the vertebral resection, or as reported by Fourney et al., a simultaneous anterior–posterior approach [9]. Yet again, these are extensive surgeries and when indicated, are good alternatives.

Thoracoscopy was increasingly used for vertebrectomy in the mid-1990s [10]. As the knowledge and the comfort of using such techniques expanded, the indications extended to vertebrectomy for tumor resections [10–12]. The improved exposure, reduction in operative time and blood loss, as well as improved recovery times was notable.

In our cases, the thoracoscopic segmental artery ligation and dissection of the parietal pleura leaving a patch over the affected vertebra, greatly assisted our resection from the posterior approach. Although the surgical time overall was 2 h for the thoracoscopy in both cases, this was due to our early experience with this technique, and will be much reduced in the future as our experience grows. The blood loss from the anterior procedure was minimal (less than 50 ml), and the patients did not encounter any complications. There was no need for a chest tube, as supported by an immediate postoperative radiograph revealing only a very small pneumothorax. A brief stay in the intensive care unit, and limited need for intravenous narcotic analgesics, further supports the minimally invasive anterior approach.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Boriani S, Weinstein JN, Biagini R. Spine update. Primary bone tumors of the spine. Terminology and surgical staging. Spine. 1997;22:1036–1044. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199705010-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomita K, Kawahara N, Baba H, Tsuchiya H, Fujita T, Toribatake Y. Total en bloc spondylectomy. A new surgical technique for primary malignant vertebral tumors. Spine. 1997;22(3):324–333. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199702010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sundaresan N, Steinberger AA, Moore F, Sachdev VP, Krol G, Hough L, et al. Indications and results of combined anterior–posterior approaches for spine tumor surgery. J Neurosurg. 1996;85(3):438–446. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.3.0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beisse R. Endoscopic surgery on the thoracolumbar junction of the spine. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(Suppl 1):S52–S65. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1124-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beisse R. Video-assisted techniques in the management of thoracolumbar fractures. Orthop Clin North Am. 2007;38(3):419–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sundaresan N, Rothman A, Manhart K, Kelliher K. Surgery for solitary metastases of the spine. Spine. 2002;27(16):1802–1806. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200208150-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gokaslan ZL, York JE, Walsh GL, McCutcheon IE, Lang FF, Putnam JB, et al. Transthoracic vertebrectomy for metastatic spinal tumors. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:599–609. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.4.0599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boriani S, Biagini R, Iure F, Bandiera S, Di Fiore M, Bandello L, et al. Resection surgery in the treatment of vertebral tumors. Chir Organi Mov. 1998;83(1–2):53–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perez-Cruet MJ, Fessler RG, Perin NI. Review: complications of minimally invasive spinal surgery. Neurosurgery. 2002;51(5 Suppl):S26–S36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dickman CA, Rosenthal D, Karahalios DG, Paramore CG, Mican CA, Apostolides PJ, et al. Thoracic vertebrectomy and reconstruction using a microsurgical thoracoscopic approach. Neurosurg. 1996;38(2):279–293. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199602000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLain R. Endoscopically assisted decompression for metastatic thoracic neoplasm. Spine. 1998;23(10):1130–1135. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199805150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verheyden AP, Hoelzl A, Lill H, Katscher S, Glasmachera S, Josten C. The endoscopically assisted simultaneous posteroanterior reconstruction of the thoracolumbar spine in prone position. Spine J. 2004;4(5):540–549. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2004.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]