Abstract

We report a rare complication of extradural arachnoid cyst following percutaneous vertebroplasty in a spinal metastasis patient. Percutaneous vertebroplasty has been established as a safe and effective treatment for osteoporotic vertebral fractures and vertebral metastatic lesions. To our knowledge, extradural arachnoid cyst following vertebroplasty has not been reported in literature. A 48-year-old woman diagnosed with adenocarcinoma underwent percutaneous vertebroplasty at the L3 vertebral level due to painful solitary spinal metastasis. At 5 months after surgery, the patient complained of low back pain radiating to the left lower extremity. MRI showed a large cystic lesion in the spinal canal at the L2–L3 level with compression to adjacent dura sac. On T1- and T2-weighted images, the signal within the cyst had the same intensity as cerebrospinal fluid. The patient underwent laminectomy for excision of the extradural cyst. Intraoperatively, a small communication between the cyst and the subarachnoid space was seen at the level of the L3 pedicle. Pathological examination revealed that the cyst wall was composed of non-specific fibrous connective tissue and the content of the cyst was the same as that of cerebrospinal fluid. Postoperatively, the patient’s symptom was relieved immediately. The iatrogenic dural injury produced by puncture of the pedicle during vertebroplasty may be the cause of formation of the extradural arachnoid cyst.

Keywords: Complication, Arachnoid cysts, Percutaneous vertebroplasty, Spinal metastasis

Introduction

Percutaneous vertebroplasty (PV) is a minimally invasive therapeutic procedure first reported in 1987 for the treatment of vertebral hemangiomas [12]. The procedure, since then, has been gradually adapted for use in the treatment of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures, multiple myelomas and vertebral metastatic lesions [2, 8, 9]. It has been proven to result in rapid pain relief with a low rate of clinical complications [13, 18]. Reported complications of PV in the treatment of spinal metastases are more common than that in osteoporotic compression fractures [10, 24, 27]. In this report, the authors document a rare complication of extradural arachnoid cyst following PV in a patient with spinal metastasis.

Case report

A 48-year-old woman was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in June 2007 and underwent tumorectomy. The surgical specimen was sent for pathology, and well-differentiated adenocarcinoma was reported. After the operation, she received six times venoclysis chemotherapy with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin. The patient suffered from low back pain in December 2007; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and bone scanning showed a metastatic lesion at the level of L3 (Fig. 1). She received PV in January 2008. Vertebroplasty was performed by means of a left unipedicular approach. After proper needle positioning, biopsy was performed through the cannula placed into the L3 vertebral body followed by injection of 1.5 cc polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) bone cement (Fig. 2). The pain was relieved dramatically after vertebroplasty. Histological examination confirmed the diagnosis of spinal metastasis. Chemotherapy with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin was performed once a month for a 3 month period postoperatively.

Fig. 1.

Prevertebroplasty bone scanning and MRI show spinal metastasis at L3 bone scanning (a), T2-weighted image, sagittal (b) and axial section at L3 (c)

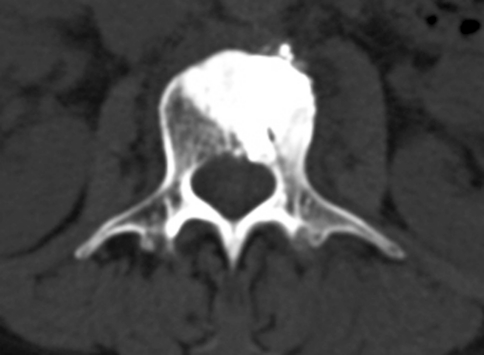

Fig. 2.

Postvertebroplasty CT, axial section at L3

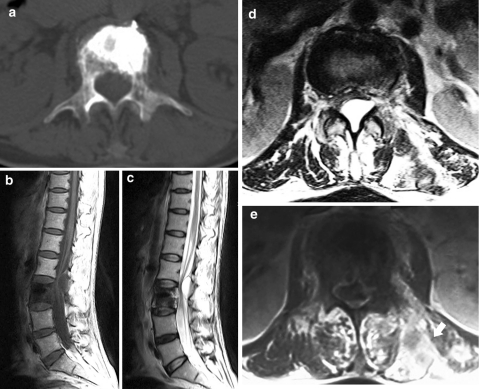

The patient presented with complaints of low back pain radiating to the left lower extremity and progressive difficulty in walking in June 2008. She denied bowel or bladder problems. Physical examination revealed weakness of the left knee extension graded at 3/5. A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed osteolytic destruction at L3 including anterolateral and posterior cortex of the vertebral body, the left pedicle and the left lamina. A soft tissue mass was found in the left paravertebral muscles. MRI showed a large cystic lesion in the spinal canal at the L2–L3 level with compression to adjacent dura sac. Axial MRI revealed that the cyst was mainly in the posterior extradural space with extension into the left lateral recess. With all sequences, the cyst fluid had the same signal intensity as cerebrospinal fluid. Metastatic lesions in the left posterior paraspinal region appeared to be heterogeneous hypersignal on T2-weighted and contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Preoperative CT shows cortical destruction of the vertebral body, the left pedicle and the left lamina at L3 axial section (a). Preoperative MRI shows a cystic lesion in the spinal canal at the L2–L3 level with compression to adjacent dura sac, T1-weighted image, sagittal (b), T2-weighted image, sagittal (c), axial section at the L2–L3 level (d). Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image shows metastatic lesions with contrast enhancement in the left posterior paraspinal region (arrow) at L3 (e)

Under diagnosis of local metastasis with extradural and paraspinal involvement, she underwent laminectomy and decompression of the spinal canal and biopsy of the left paraspinal mass. After removing the laminae at the involved level, a large, thin-walled cyst was encountered. The cystic fluid was colorless like cerebrospinal fluid. A small communication between the cyst and the subarachnoid space was seen at the level of the L3 pedicle. The spinal cord and the nerve root appeared to be completely decompressed after the cystic mass was removed. Pathological examination revealed that the cyst wall was composed of non-specific fibrous connective tissue and the content of the cyst was the same as that of the cerebrospinal fluid. The left paraspinal mass contained metastatic adenocarcinoma cells. Postoperatively, the patient experienced complete relief of the leg pain and partial relief of the low back pain. The patient’s strength in the left lower extremities was improved. She was discharged 1 week later. However, her general condition progressively deteriorated and she died 6 months later.

Discussion

As survival time increases for many cancers, it is likely that the incidence and prevalence of spinal metastases will also increase. Because of their immunocompromised status after the performed operation for primary tumor, ongoing chemotherapy, poor nutrition and comorbid medical conditions, patients who have metastatic spine tumors are debilitated and cannot tolerate the open surgical trauma and have a high complication rate [17, 30, 33, 34]. For these patients with limited life expectancies, the appropriate treatment is to achieve relief of pain and to regain function, thus improving the quality of the life as quickly as possible.

PV is an effective minimally invasive treatment option for vertebral metastases without neural compression. Compared with radiotherapy alone, this procedure provides immediate structural support, and stabilizes and reinforces the remaining bone structure. The chemical and thermal cytotoxicity of PMMA cement also may have analgesic and anti-tumor effects [4]. Although vertebroplasty gives low peri- and postsurgery morbidity and good pain control [1, 5, 11], it does not allow good local control of disease and may cause local metastases [6]. So, vertebral augmentation should be combined with radiotherapy or chemotherapy to achieve a better local control of the tumor [14, 19]. Spinal solitary metastasis was first discovered in this patient 6 months after surgery for the primary tumor. She presented with low back pain without any neurological deficit. Because of the debilitated status of this patient and insensitivity to radiotherapy of the tumor cells, we chose vertebroplasty in combination with chemotherapy to treat this patient.

The rate of cement extravasation in spinal metastases is higher than that in osteoporotic compression fractures due to cortical breakdown [3, 9]. Characteristics of metastatic lesions may also cause special complication in this kind of patients. Chen et al. [6] reported local metastases along the needle tract of PV. His explanation for this complication was that tumor behavior was aggressive and no adjuvant therapy was used to control the tumor. For our patient, in spite of well-differentiated tumor cells and periodical postvertebroplasty chemotherapy, local metastasis along the tract was discovered in half a year. It might be related to high-grade malignancy of the tumor cells and insensitivity to radiotherapy and chemotherapy, which make local control of vertebral metastatic lesions more difficult.

To our knowledge, extradural arachnoid cysts following vertebroplasty have not been reported in literature. The causes of spinal extradural arachnoid cysts remain unclear. It is reported that they are extradural outpouchings of arachnoid that communicate with the intraspinal subarachnoid space via a small dural defect [22]. Most of the spinal extradural arachnoid cysts are often attributed to congenital defects [7]. Another possibility is that they develop secondary to inflammation, trauma or iatrogenic causes such as lumbar puncture, anesthetic procedures or intradural surgery [16, 28, 29, 31]. In the current case, we did not find cysts in the spinal canal prevertebroplasty, so congenital cause can be ruled out. There was also no evidence of arachnoiditis demonstrated on imaging studies. This cyst was formed after vertebroplasty and was located mainly on the operated side. So, it is most likely that the dura was injured by puncture of the pedicle during vertebroplasty, which led to the formation of the cyst.

Pathologically, the wall of arachnoid cysts consists of fibrous connective tissue with an inner single-cell arachnoid lining; however, the inner arachnoid lining is sometimes absent [26]. Because of the absence of the inner arachnoid lining in the cyst wall in our case, it is unlikely that active fluid secretion from the cyst wall causes cyst enlargement. Some authors have postulated that a ball-valve mechanism in the communicating pedicle is associated with pulsatile cerebrospinal fluid dynamics and results in cystic expansion [15, 22, 25]. According to this theory, we postulate that iatrogenic dural injury formed a unidirectional “valve” on the arachnoid membrane, which let cerebrospinal fluid in but not out. So, the cyst enlarged progressively and eventually caused symptoms.

Extradural arachnoid cysts are rare lesions; the final diagnosis should be based on combined radiological findings, intraoperative inspection and histopathological results. CT myelography and kinematic MRI can help evaluate the presence of communications between the cyst and the subarachnoid space; however, these studies were not performed in our case. The preferred treatment of extradural arachnoid cysts is complete surgical removal. Open surgery typically results in an excellent prognosis regardless of the cyst’s size [20, 21, 32]. However, minimally invasive surgical techniques including percutaneous aspiration under fluoroscopic guidance and selective closure of the dural defect based on cinematic MRI [23] might be better treatment options for patients who have metastatic lesions.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Appel NB, Gilula LA. Percutaneous vertebroplasty in patients with spinal canal compromise. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:947–951. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.4.1820947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barr JD, Barr MS, Lemley TJ, McCann RM. Percutaneous vertebroplasty for pain relief and spinal stabilization. Spine. 2000;25:923–928. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200004150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barragan-Campos HM, Vallee JN, Lo D, Cormier E, Jean B, Rose M, Astagneau P, Chiras J. Percutaneous vertebroplasty for spinal metastases: complications. Radiology. 2006;238:354–362. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2381040841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belkoff SM, Molloy S. Temperature measurement during polymerization of polymethylmethacrylate cement used for vertebroplasty. Spine. 2003;28:1555–1559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calmels V, Vallee JN, Rose M, Chiras J. Osteoblastic and mixed spinal metastases: evaluation of the analgesic efficacy of percutaneous vertebroplasty. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:570–574. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen YJ, Chang GC, Chen WH, Hsu HC, Lee TS. Local metastases along the tract of needle: a rare complication of vertebroplasty in treating spinal metastases. Spine. 2007;32:615–618. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318154c5e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi JY, Kim SH, Lee WS, Sung KH. Spinal extradural arachnoid cyst. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2006;148:579–585. doi: 10.1007/s00701-006-0744-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortet B, Cotten A, Boutry N, Flipo RM, Duquesnoy B, Chastanet P, Delcambre B. Percutaneous vertebroplasty in the treatment of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures: an open prospective study. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:2222–2228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotten A, Dewatre F, Cortet B, Assaker R, Leblond D, Duquesnoy B, Chastanet P, Clarisse J. Percutaneous vertebroplasty for osteolytic metastases and myeloma: effects of the percentage of lesion filling and the leakage of methyl methacrylate at clinical follow-up. Radiology. 1996;200:525–530. doi: 10.1148/radiology.200.2.8685351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deramond H, Depriester C, Galibert P, Le Gars D. Percutaneous vertebroplasty with polymethylmethacrylate. Technique, indications, and results. Radiol Clin North Am. 1998;36:533–546. doi: 10.1016/S0033-8389(05)70042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fourney DR, Schomer DF, Nader R, Chlan-Fourney J, Suki D, Ahrar K, Rhines LD, Gokaslan ZL. Percutaneous vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty for painful vertebral body fractures in cancer patients. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:21–30. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.1.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galibert P, Deramond H, Rosat P, Le Gars D. Preliminary note on the treatment of vertebral angioma by percutaneous acrylic vertebroplasty. Neurochirurgie. 1987;33:166–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garfin SR, Yuan HA, Reiley MA. New technologies in spine: kyphoplasty and vertebrosplasty for the treatment of painful osteoporotic compression fractures. Spine. 2001;26:1511–1515. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200107150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerszten PC, Germanwala A, Burton SA, Welch WC, Ozhasoglu C, Vogel WJ. Combination kyphoplasty and spinal radiosurgery: a new treatment paradigm for pathological fractures. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;18:e8. doi: 10.3171/foc.2005.18.3.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gortvai P. Extradural cysts of the spinal canal. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1963;26:223–230. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.26.3.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffman EP, Garner JT, Johnson D, Shelden CH. Traumatic arachnoidal diverticulum associated with paraplegia. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1973;38:81–85. doi: 10.3171/jns.1973.38.1.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holman PJ, Suki D, McCutcheon I, Wolinsky JP, Rhines LD, Gokaslan ZL. Surgical management of metastatic disease of the lumbar spine: experience with 139 patients. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:550–563. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.5.0550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hulme PA, Krebs J, Ferguson SJ, Berlemann U. Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty: a systematic review of 69 clinical studies. Spine. 2006;31:1983–2001. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000229254.89952.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang JS, Lee SH. Efficacy of percutaneous vertebroplasty combined with radiotherapy in osteolytic metastatic spinal tumors. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:243–248. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.3.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kulkarni AG, Goel A, Thiruppathy SP, Desai K. Extradural arachnoid cysts: a study of seven cases. Br J Neurosurg. 2004;18:484–488. doi: 10.1080/02688690400012368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu JK, Cole CD, Sherr GT, Kestle JR, Walker ML. Noncommunicating spinal extradural arachnoid cyst causing spinal cord compression in a child. J Neurosurg. 2005;103:266–269. doi: 10.3171/ped.2005.103.3.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCrum C, Williams B. Spinal extradural arachnoid pouches. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 1982;57:849–852. doi: 10.3171/jns.1982.57.6.0849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neo M, Koyama T, Sakamoto T, Fujibayashi S, Nakamura T. Detection of a dural defect by cinematic magnetic resonance imaging and its selective closure as a treatment for a spinal extradural arachnoid cyst. Spine. 2004;29:E426–E430. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000141189.41705.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pilitsis JG, Rengachary SS. The role of vertebroplasty in metastatic spinal disease. Neurosurg Focus. 2001;11:e9. doi: 10.3171/foc.2001.11.6.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rohrer DC, Burchiel KJ, Gruber DP. Intraspinal extradural meningeal cyst demonstrating ball-valve mechanism of formation. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:122–125. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.1.0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato K, Nagata K, Sugita Y. Spinal extradural meningeal cyst: correct radiological and histopathological diagnosis. Neurosurg Focus. 2002;13:ecp1. doi: 10.3171/foc.2002.13.4.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh K, Samartzis D, Vaccaro AR, Andersson GB, An HS, Heller JG. Current concepts in the management of metastatic spinal disease. The role of minimally-invasive approaches. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:434–442. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B4.17282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sklar EM, Quencer RM, Green BA, Montalvo BM, Post MJ. Complications of epidural anesthesia: MR appearance of abnormalities. Radiology. 1991;181:549–554. doi: 10.1148/radiology.181.2.1924803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spiegelmann R, Rappaport ZH, Sahar A. Spinal arachnoid cyst with unusual presentation. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1984;60:613–616. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.60.3.0613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Street J, Fisher C, Sparkes J, Boyd M, Kwon B, Paquette S, Dvorak M. Single-stage posterolateral vertebrectomy for the management of metastatic disease of the thoracic and lumbar spine: a prospective study of an evolving surgical technique. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:509–520. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e3180335bf7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taguchi Y, Suzuki R, Okada M, Sekino H. Spinal arachnoid cyst developing after surgical treatment of a ruptured vertebral artery aneurysm: a possible complication of topical use of fibrin glue. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:526–529. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.84.3.0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tureyen K, Senol N, Sahin B, Karahan N. Spinal extradural arachnoid cyst. Spine J. 2009;9:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vitaz TW, Oishi M, Welch WC, Gerszten PC, Disa JJ, Bilsky MH. Rotational and transpositional flaps for the treatment of spinal wound dehiscence and infections in patient populations with degenerative and oncological disease. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:46–51. doi: 10.3171/spi.2004.100.1.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weigel B, Maghsudi M, Neumann C, Kretschmer R, Muller FJ, Nerlich M. Surgical management of symptomatic spinal metastases. Postoperative outcome and quality of life. Spine. 1999;24:2240–2246. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199911010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]