Abstract

The objective of this study was to describe an adult male patient with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) associated with thoracic spinal cord herniation (TSCH). TSCH is a scarce entity presented as a displacement of thoracic cord through an anterior or anterolateral dural defect. More importantly, the co-occurrence of AS and thoracic spinal cord herniation is exceptional. To date, only one case of SCH in association with AS has been reported in the literature. A 56-year-old male patient presented with the progressive difficulty in walking and numbness of both lower limbs for the past 18 months. The patient was diagnosed as AS when he was 30 years old. Sagittal MRI of thoracic spine showed dural defect of the posterior aspect of T11 and 12 vertebral bodies. Axial T2-weighted MRI demonstrated that spinal cord was displaced ventrally and to the right. The diagnosis of TSCH with AS was established. The prognosis was explained to the patient. We recommended duraplasty for dural repair to the patient, but he refused surgery. The results demonstrated that TSCH associated with long-standing AS was very uncommon, and MRI is recommended to rule out SCH in the long-standing AS patients with neurologic symptoms. The SCH in AS might be caused by inflammation, and thoracolumbar hyperkyphosis results from AS might be associated with the development of SCH.

Keywords: Ankylosing spondylitis, Thoracic spinal cord herniation

Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory rheumatic disorder known as spondyloarthropathies [1] that primarily affects the spine and axial joints, causing pain, stiffness and a progressive thoracolumbar kyphotic deformity [2]. In the untreated cases, the long-lasting persistent inflammation causes progressive rigidity of the entire spine which could subsequently lead to two major complications of AS: the hyperkyphosis of thoracolumbar spine and neurological complications [2]. Lumbosacral radiculopathies, cauda equine syndrome and compression of the spinal cord have been reported as extra-articular manifestations of AS [3, 4].

Thoracic spinal cord herniation (TSCH) is a scarce entity presented as a displacement of thoracic cord through an anterior or anterolateral dural defect. More importantly, the co-occurrence of AS and thoracic spinal cord herniation is exceptional. Which one of these two diseases antedated the other is unsure. In addition, neurological complications are very rarely described in patients with AS and SCH. To date, only one case of SCH in association with AS has been reported in the literature [5]. Here, a new case diagnosed with thoracic spinal cord herniation associated with ankylosing spondylitis in our center was reported. By incorporating the improved understanding on the pathogenesis of SCH, the potential association of TSCH in long-standing AS patients was discussed.

Case report

A 56-year-old male patient visited our outpatient service with the chief complaint of progressive difficulty in walking and numbness of both lower limbs for the past 18 months. The patient was diagnosed as AS when he was 30 years old, without a systemic therapy for AS but only analgesics for symptomatic relief. He had no other history of trauma or surgery.

The physical examination showed a kyphotic deformity in thoracolumbar spine with decreased sensation below the saddle area, marked weakness in muscular strength of the bilateral lower extremities (grade 3/5 of the iliopsoas muscle and 0/5 of the extensor hallucis longus muscles) and increased muscle tone. In addition, the reflexes of patella tendon and Achilles tendon were decreased. The ankle clonus and Babinski signs were positive in both sides.

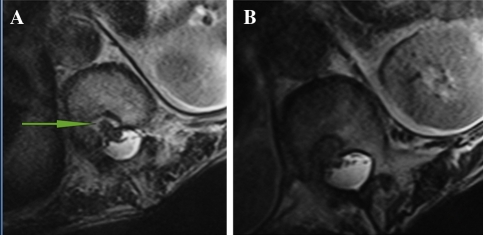

The blood tests (C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate) yielded normal results. Lateral lumbar spine X-ray film demonstrated ankylosis in apophyseal joints, and the characteristic undulating osseous outgrowths in the anterior aspect of lumbar vertebrae and disc spaces, and the kyphosis of thoracolumbar with a Cobb angle of 37 degree (Fig. 1). Sagittal MRI of thoracic spine showed dural defect of the posterior aspect of T11 and 12 vertebral bodies. At this level, ventral subarachnoid space was obliterated, and a “C” shaped anterior kinking of the spinal cord was adhered into the dural defect in vertebral bodies. A relative enlargement of the dorsal subarachnoid space was present (Fig. 2a, b). Axial T2-weighted MRI demonstrated that spinal cord was displaced ventrally and to the right (Fig. 3a, b).

Fig. 1.

A 56-year-old man with spinal cord herniation and long-standing ankylosing spondylitis. Plain radiograph shows typical changes of long-standing ankylosing spondylitis (bamboo spine)

Fig. 2.

Sagittal T1-weighted MRI (a) and T2-weighted MRI (b) show ventral displacement of the spinal cord, with a “C” shaped anterior kinking of the spinal cord adhered into the dural defect (arrows in a). In addition, T2-weighted MRI (b) shows forward protrusion of the cerebrospinal fluid into the vertebral body defect (T11–12 levels, arrows in b)

Fig. 3.

Axial T2-weighted MRI (a, b) demonstrated that spinal cord was displaced ventrally and to the right (arrows in a)

The diagnosis of TSCH with AS was established. The prognosis was explained to the patient. For the purpose of reversing or stopping the progression of serious neurologic deficits, we recommended duraplasty for dural repair to the patient, but he gave up this treatment strategy because of financial concern.

Discussion

Recently, neurological complications have been reported in patients with AS [2, 6]. Cauda equine syndrome and the compression of the spinal cord have been reported as extra-articular manifestations of AS [3, 4]. In the current patient, the progressive difficulty in walking and numbness of both lower limbs during the past 18 months drived us to believe that it may be related to spinal stenosis secondary to AS. However, the severity and pattern of neurological dysfunction presented in the case were atypical in AS patients. Then we did the MRI of the thoracic spine, which showed a typical TSCH (Figs. 2a, b, 3a, b).

SCH through an anterior dural defect was a rare clinical entity, although more SCH were reported in the past years because of the increased use of MRI [7]. It has been shown the TSCH patients were initially asymptomatic [8]. In addition, these symptoms typically are long lasting before the precise diagnosis [9, 10]. In the literature, most of the patients typically present with Brown-Séquard syndrome [11–15]. Furthermore, the diagnosis of TSCH may be delayed because of its nonspecific clinical features. Regarding the patient reported here, the history of long-lasting AS, but fast progression of neurological deficits within a short period, was similar to that of TSCH reported although the clinical manifestation was atypical (paralysis and paraparesis) in contrast with typical ISCH (Brown-Séquard syndrome) [9, 10].

TSCH associated with long-standing AS was very uncommon, and there were only two cases reported, including our patient. Baur et al. [5] first reported the case of a 50-year-old man with SCH and AS. Displacement of the conus medullaris and cauda equina fibers into the bony defect on the posterior portions of T12 and L1 vertebral bodies was identified [5]. Compared with that patient [5], the similar long-standing history of AS was found in our patient. In addition, both cases suffered neurologic deterioration in bilateral lower extremities.

The SCH can be caused by trauma, operation, or unknown factors which were defined as idiopathic SCH (ISCH) [7]. Our patient has no history of trauma or operation, indicating the SCH was idiopathic. ISCH was first reported by Wortzman et al. [16] in 1974. It was well accepted that the presence of a dural defect is considered to be a necessary condition of SCH [17, 18]. Najjar et al. [19] proposed that an inflammation might lead to arachnoid adhesion formation and erosion through the dura forming an idiopathic dural defect and subsequent spinal cord herniation. The inflammation resulting from incarceration of the cord [20] may also cause the increased thickness of dorsal arachnoid [17, 21, 22]. In addition, within several mechanisms suggested as cause of nervous system involvement in AS, inflammation and compression are the main causative mechanisms [23, 24]. It has been illustrated in AS patients that the neurologic deficit might be caused by inflammation. Dural inflammatory, arachnoiditis and dorsal bone elements of spine erosions were identified as causes of caudal equine syndrome (CES) [24]. The CES–AS syndrome has been described in numerous studies [3], and the prevalence of neurologic findings in the CES–AS syndrome was very high. Nearly all patients presented with a symptom of sensory or reflex loss [3]. In AS, the erosive inflammatory condition has preference toward erosion of openings where tendons and ligaments insert into bone, and then it causes the body’s biochemistry to attempt to fill in the defect with new bone growth [25]. From above, inflammation not only increases the risk of neurological deficit of AS, but also increases the risk for SCH. Hence, despite the uncertainty of temporal relationship between TSCH and AS, we presume that their coexistence in our patient is not accidental. It is worthwhile to note that despite the neurological deficits are similar in the patients with CES or SCH, the occurrence of CES in the patients with TSCH has not been reported in the literature. In addition, in contrast to the CES, in our case a ventral but not dorsal dural defect was found and the spinal cord surrounded with the cerebrospinal fluid was herniated into the back of the vertebral bodies and disc space.

In the patient with SCH in AS reported by Baur et al. [5], histological examination showed inflammatory cells on the fibrotic-thickened arachnoid membrane. The results were consistent with the hypothesis of Najjar et al. [19] and strongly hint that SCH was caused by the inflammation. Although further verification on the proposed mechanism by histological diagnosis study is not available in the present case, the history and clinical symptom of the current case were similar as the one reported by Baur et al. [5]. Hence, it is possible that the SCH observed in the current case was also caused by inflammation.

Thoracolumbar kyphosis caused by AS might also be involved in the development of SCH. In the literature, most ISCH located between T2 and T10 [21]. The SCH in AS reported by Baur et al. [5] and here, however, was found at the T12–L1 and T11–12 levels, both of which were the apical vertebrae of thoracolumbar kyphosis. In both cases, there might be bony defects on the posterior vertebral bodies and Baur et al. [5] found the conus medullaris and the cauda fibers were displaced anteriorly into the bony defect caused by AS. Moreover, it has been reported that with the hyperkyphosis of thoracolumbar spine, the spinal cord lay directly along the ventral dura, and the dural defect would lead to adhesion and frank herniation of spinal cord [26]. Such a prolonged pathophysiological process would fit with the long-standing, progressive course observed in our patient. Hence we speculated that thoracolumbar kyphosis secondary to AS leads to the adhesion of the thoracic nerve roots, contributing to the development of SCH.

For the treatment of ISCH, management options include observation and surgical intervention [27–29], and conservative management is typically advocated for the patients who are neurologically stable without significant motor deficits [13, 30]. When surgery is recommended, the herniated spinal cord is repaired by either enlarging the dural defect or repairing the dural defect [12, 13, 27, 31]. Generally closure of the dural defect is preferred because it may be less associated with recurrent spinal cord tethering or epidural CSF collections [27]. Up to now, surgery with duraplasty has been widely performed with good results in most cases with Brown-Séquard syndrome [32]. In the case reported by Baur et al. [5], resection of the adhesions of the cauda fibers and release of the conus medullaris from the dural defect resulted in marked improvement of the neurological symptoms.

Recently, Barbagallo et al. [18] described two cases with SCH at the vertebral body level, where the surgical outcome was poor. In particular, he hypothesized that vertebral body level SCH occurring into a vertebral body cavity may form a distinct subgroup with both an atypical presentation and a poor prognosis. In our case, the SCH also occurred at vertebral body levels (T11–T12). Despite our patient had a history of long-standing AS and neurologic deficits, and the surgical outcome appeared less predictable, we prefer operation for dural repair for the purpose of reversing or stopping the progression of neurologic deficits. Unfortunately, our patient refused surgery.

In summary, the present case is of interest because of the unusual association between AS and TSCH. To our knowledge, this is the second case reported in the literature. A long-standing AS patients with severe neurologic deficits were diagnosed as TSCH with AS after MRI examination. Hence, we suggest performing MRI examination for the long-standing AS patients with neurologic symptoms to rule out SCH. The SCH in AS might be caused by inflammation, and thoracolumbar hyperkyphosis results from AS might be associated with the development of SCH, although the possibility of pre-existing SCH cannot be excluded.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gran JT, Husby G, Hordvik M. Prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis in males and females in a young middle-aged population of Tromso, northern Norway. Ann Rheum Dis. 1985;44:359–367. doi: 10.1136/ard.44.6.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilkinson M, Bywaters EG. Clinical features and course of ankylosing spondylitis; as seen in a follow-up of 222 hospital referred cases. Ann Rheum Dis. 1958;17:209–228. doi: 10.1136/ard.17.2.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn NU, Ahn UM, Nallamshetty L, Springer BD, Buchowski JM, Funches L, Garrett ES, Kostuik JP, Kebaish KM, Sponseller PD. Cauda equina syndrome in ankylosing spondylitis (the CES–AS syndrome): meta-analysis of outcomes after medical and surgical treatments. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14:427–433. doi: 10.1097/00002517-200110000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oh DH, Jun JB, Kim HT, Lee SW, Jung SS, Lee IH, Kim SY. Transverse myelitis in a patient with long-standing ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2001;19:195–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baur A, Stabler A, Psenner K, Hamburger C, Reiser M. Imaging findings in patients with ventral dural defects and herniation of neural tissue. Eur Radiol. 1997;7:1259–1263. doi: 10.1007/s003300050286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tyrrell PN, Davies AM, Evans N. Neurological disturbances in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994;53:714–717. doi: 10.1136/ard.53.11.714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selviaridis P, Balogiannis I, Foroglou N, Hatzisotiriou A, Patsalas I. Spontaneous spinal cord herniation: recurrence after 10 years. Spine J. 2009;9:e17–e19. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Senturk S, Guzel A, Guzel E. Atypical clinical presentation of idiophatic thoracic spinal cord herniation. Spine. 2008;33:E474–E477. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318178e624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isu T, Iizuka T, Iwasaki Y, Nagashima M, Akino M, Abe H. Spinal cord herniation associated with an intradural spinal arachnoid cyst diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosurgery. 1991;29:137–139. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199107000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White BD, Tsegaye M. Idiopathic anterior spinal cord hernia: under-recognized cause of thoracic myelopathy. Br J Neurosurg. 2004;18:246–249. doi: 10.1080/02688690410001732670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dix JE, Griffitt W, Yates C, Johnson B. Spontaneous thoracic spinal cord herniation through an anterior dural defect. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:1345–1348. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saito T, Anamizu Y, Nakamura K, Seichi A. Case of idiopathic thoracic spinal cord herniation with a chronic history: a case report and review of the literature. J Orthop Sci. 2004;9:94–98. doi: 10.1007/s00776-003-0730-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massicotte EM, Montanera W, Ross Fleming JF, Tucker WS, Willinsky R, TerBrugge K, Fehlings MG. Idiopathic spinal cord herniation: report of eight cases and review of the literature. Spine. 2002;27:E233–E241. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200205010-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyake S, Tamaki N, Nagashima T, Kurata H, Eguchi T, Kimura H (1999) Idiopathic spinal cord herniation. Report of two cases and review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus 7:e6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Brugieres P, Malapert D, Adle-Biassette H, Fuerxer F, Djindjian M, Gaston A. Idiopathic spinal cord herniation: value of MR phase-contrast imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:935–939. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wortzman G, Tasker RR, Rewcastle NB, Richardson JC, Pearson FG. Spontaneous incarcerated herniation of the spinal cord into a vertebral body: a unique cause of paraplegia. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1974;41:631–635. doi: 10.3171/jns.1974.41.5.0631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tekkok IH. Spontaneous spinal cord herniation: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:485–491. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200002000-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barbagallo GM, Marshman LA, Hardwidge C, Gullan RW. Thoracic idiopathic spinal cord herniation at the vertebral body level: a subgroup with a poor prognosis? Case reports and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:369–374. doi: 10.3171/spi.2002.97.3.0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Najjar MW, Baeesa SS, Lingawi SS (2004) Idiopathic spinal cord herniation: a new theory of pathogenesis. Surg Neurol 62:161–170; discussion 170–171. doi:10.1016/j.surneu.2003.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.White BD, Firth JL. Anterior spinal hernia: an increasingly recognised cause of thoracic cord dysfunction. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:1433–1435. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.11.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marshman LA, Hardwidge C, Ford-Dunn SC, Olney JS. Idiopathic spinal cord herniation: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:1129–1133. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199905000-00112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tronnier VM, Steinmetz A, Albert FK, Scharf J, Kunze S. Hernia of the spinal cord: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1991;29:916–919. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199112000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramos-Remus C, Russell AS, Gomez-Vargas A, Hernandez-Chavez A, Maksymowych WP, Gamez-Nava JI, Gonzalez-Lopez L, Garcia-Hernandez A, Meono-Morales E, Burgos-Vargas R, Suarez-Almazor ME. Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in three geographically and genetically different populations of ankylosing spondylitis and other spondyloarthropathies. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57:429–433. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.7.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tullous MW, Skerhut HE, Story JL, Brown WE, Jr, Eidelberg E, Dadsetan MR, Jinkins JR. Cauda equina syndrome of long-standing ankylosing spondylitis. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:441–447. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.73.3.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khedr EM, Rashad SM, Hamed SA, El-Zharaa F, Abdalla AK (2009) Neurological complications of ankylosing spondylitis: neurophysiological assessment. Rheumatol Int. doi:10.1007/s00296-009-0841-7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Borges LF, Zervas NT, Lehrich JR. Idiopathic spinal cord herniation: a treatable cause of the Brown-Sequard syndrome––case report. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:1028–1032. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199505000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maira G, Denaro L, Doglietto F, Mangiola A, Colosimo C. Idiopathic spinal cord herniation: diagnostic, surgical, and follow-up data obtained in five cases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;4:10–19. doi: 10.3171/spi.2006.4.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gwinn R, Henderson F. Transdural herniation of the thoracic spinal cord: untethering via a posterolateral transpedicular approach. Report of three cases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004;1:223–227. doi: 10.3171/spi.2004.1.2.0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saito A, Takahashi T, Sato S, Kumabe T, Tominaga T. Modified surgical technique for the treatment of idiopathic spinal cord herniation. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2006;49:120–123. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-932171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams RF, Anslow P. The natural history of transdural herniation of the spinal cord: case report. Neuroradiology. 2001;43:383–387. doi: 10.1007/s002340000469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ammar KN, Pritchard PR, Matz PG, Hadley MN (2005) Spontaneous thoracic spinal cord herniation: three cases with long-term follow-up. Neurosurgery 57:E1067 (discussion E1067) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Sasani M, Ozer AF, Vural M, Sarioglu AC. Idiopathic spinal cord herniation: case report and review of the literature. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32:86–94. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2009.11760757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]