Abstract

Spinal hydatid cyst is a serious and unusual infectious disease. There is little information on infections caused by cestodes in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Although infrequent, infections by cestodes constitute a cause of disease in HIV-infected patients, especially in endemic areas. This report presents, for the first time in the literature, primary spinal cyst hydatid in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

Keywords: Hydatid cyst, Spinal, HIV, Primary

Introduction

Hydatid cyst disease is one of the most important parasitic diseases caused by infection with the pathogen Echinococcus granulosus [1, 2].

Infection in humans occurs by means of direct contact with the definitive host or its feces or by ingesting food infected by the parasite’s eggs. The liver and lungs are the most frequent localizations of E. granulosus infection. While hydatid cysts tend to develop in the liver or lungs, they may be found in any organ of the body. Musculoskeletal system hydatid disease accounts for 0.5–2.0% of all cases, and spinal hydatid cyst accounts for 50% of these cases [1–3].

The most common parasitic infections in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients are protozoans. Infections by helminths have been described less often. The most common helminths causing disease in HIV-infected patients are nematodes, especially Strongyloides stercoralis, and trematodes such as Schistosoma species. Parasitic infections by cestodes in HIV-infected patients are very unusual [4].

In this report, we describe for the first time in the literature a case of primary spinal cyst hydatid in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Case report

A 29-year-old male patient was admitted to our department with back pain, progressive weakness in the legs and sensory loss.

A general physical examination revealed no abnormality. The neurological examination demonstrated Frankel C paraparesis and hypoesthesia under the level of D5 dermatome. Deep tendon reflexes were absent, and the patient had urinary and anal incontinence.

Laboratory data revealed hemoglobin of 14.4 g/dl and white blood cell count of 6,400 cells/ml. HIV-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) antibody test was positive. CD4 T-lymphocyte count was 12 cells/ml and plasma HIV-1 RNA load was 460,000 copies/ml. Serological tests for hydatid cyst, specific ELISA and Western blot analysis were negative.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the thoracal region showed a multilocular cystic paravertebral lesion extending to the epidural space. The lesion infiltrated the posterior paravertebral muscles as well as right neural foramina and posterior epidural space. The lesion was also multicystic in epidural space. The wall of the lesion demonstrated enhancement after administration of contrast material (Figs. 1, 2, 3).

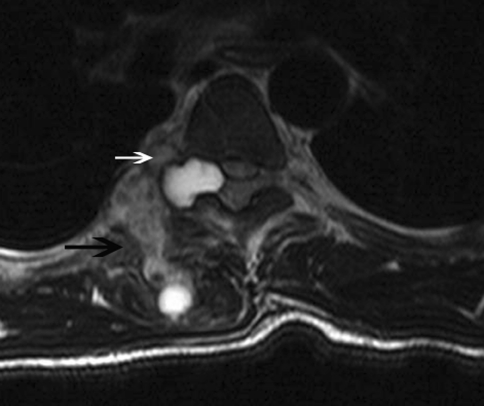

Fig. 1.

Transverse T2-weighted image reveals heterogeneously hyperintense multiloculated lesion infiltrating paravertebral muscles (black arrow) as well as epidural space through neural foramina (white arrow)

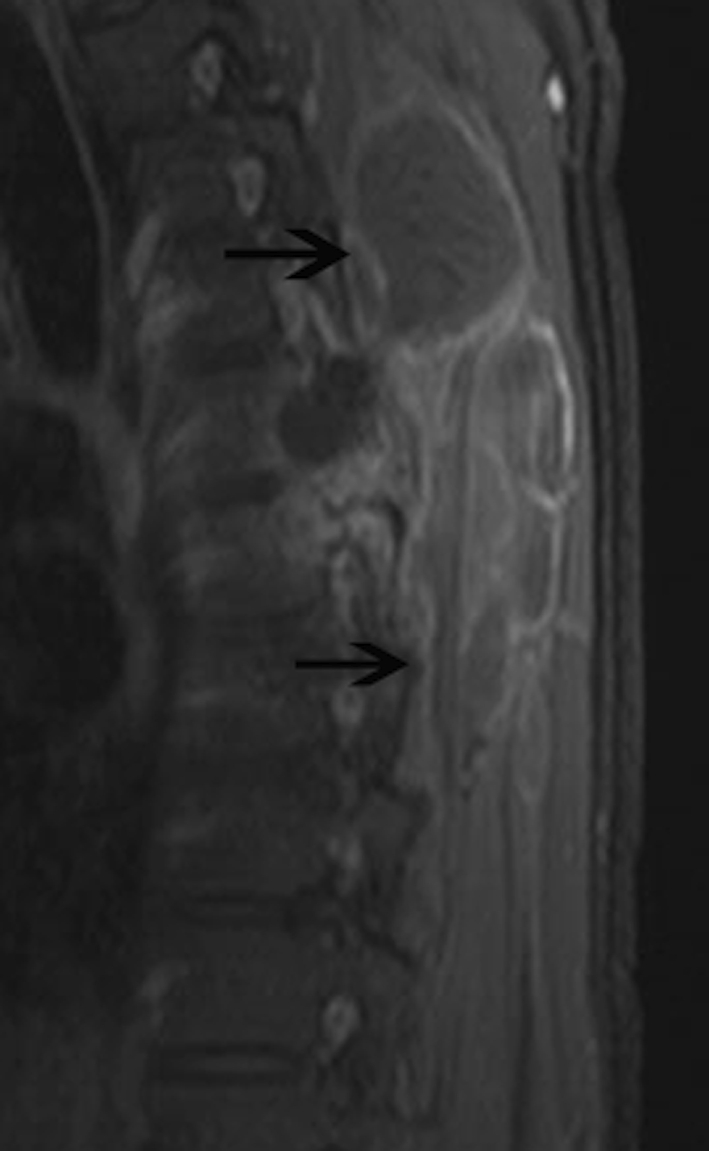

Fig. 2.

Sagittal T1-weighted fat-saturated image obtained after administration of intravenous contrast material reveals multiloculated cystic lesions (black arrows) with rim enhancement in the paravertebral muscles

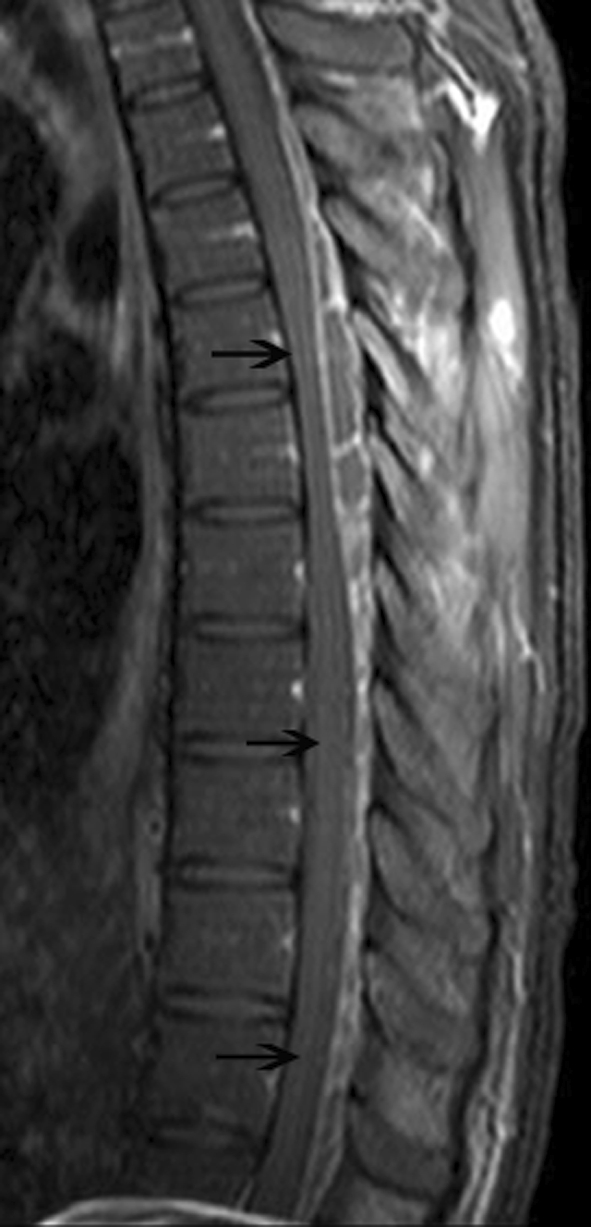

Fig. 3.

Sagittal T1-weighted fat-saturated image obtained after administration of intravenous contrast material reveals rim enhanced loculated cystic lesions through posterior epidural space (black arrows)

Lymphoma, Kaposi sarcoma, tuberculosis, and other opportunistic infections of the spine were considered in the differential diagnosis.

The patient underwent exploratory surgery using a posterior approach. Various vesicles were seen in the paravertebral region. The lesion began at the fourth thoracal vertebra, eroding the posterior vertebral structures and extending to the epidural space. The lesion was removed gross totally via thoracal 4–7 laminectomy, and the cavity was irrigated with hypertonic saline.

Histopathological examination revealed an amorphous acellular cuticular lesion compatible with hydatid cyst (Fig. 4).

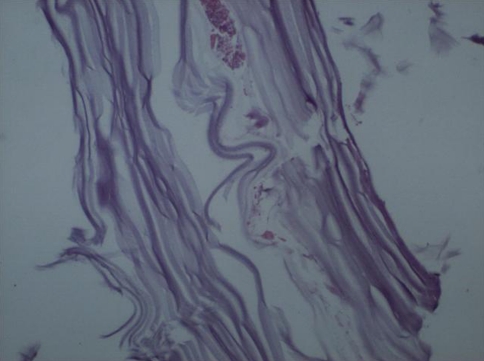

Fig. 4.

Original histological photomicrograph of the cuticular layer of the hydatid cyst (hematoxylin and eosin, ×40)

Albendazole treatment was started in the early postoperative stage and three cycles of treatment (each cycle consisted of 15 mg/kg/day albendazole for 4 weeks) were completed.

The postoperative stage was unremarkable without any additional problem. The patient has a Frankel D neurological score after the postoperative first week.

Discussion

Cystic hydatid disease is caused by an infection by the tapeworm cestode E. granulosus, and is mostly seen in areas where sheep and cattle are raised, particularly in Mediterranean countries [1]. Humans can be infected by ingesting the eggs of the parasite. The liver and lungs trap oncospheres that migrate from the intestine to the portal circulation. Spinal hydatid cysts account for 1% of all cases of hydatid disease [1, 2]. The disease usually spreads over the spine by direct extension from pulmonary, abdominal, or pelvic infestation, and most commonly affects the dorsal region of the spine. Spinal hydatid cysts are located most commonly at the thoracic (52%), followed by the lumbar (37%) and then the cervical and sacral levels [1].

There is little information in the literature about hydatid disease and HIV infection, suggesting that it might indeed be a rare association. Ramos et al. [4] reported hydatid cysts of the lung in HIV-infected patients and described the lesions as solitary node or multiple cannon ball shadows.

The spinal tumor-like lesion was initially considered as lymphoma or kaposi sarcoma in this case. MRI findings and the patient’s HIV history reinforced these possibilities. Two-layered wall, water-lily sign are published MRI findings of cyst hydatid disease but unfortunately none of these findings were seen in our case [5–7]. Hydatid disease may have appearance similar to abscesses, hematomas, metastases or solid soft tissue tumors such as myxoid liposarcoma and desmoid [8–14]. The establishment of an accurate preoperative diagnosis in this condition is of paramount importance so that one can avoid percutaneous needle or open biopsy, as these procedures can lead to inadvertent cyst rupture with the consequent risk of anaphylaxis and dissemination to other organs [14]. But the diagnosis may still be difficult because of the low prevalence of the disease and the unusual location of the lesion.

Hydatid cyst diagnosis could be established only by intraoperative observations and histopathological investigation for this case.

Previous studies showed that humoral and cellular immunity play essential roles in response to human hydatidosis. Th1 and Th2 cell activation and the expression of immunoglobulin isotypes such as IgE and IgG occur at different stages of the infection and define progression of the disease and the clinical outcomes [15, 16]. Failure of humoral and cellular immunity and severe immunodeficiency to antigens are seen during the AIDS course [17]. Impaired immune response could lead to uncontrolled and rapid progression of the parasitic infections in HIV patients like our case [4, 17].

In conclusion, larval cestode infections are uncommon but do occur in HIV-infected patients. Hydatid cyst should be considered in the differential diagnosis of spinal lesions in HIV patients.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kalkan E, Cengiz SL, Ciçek O, Erdi F, Baysefer A. Primary spinal intradural extramedullary hydatid cyst in a child. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30:297–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalkan E, Torun F, Erdi F, Baysefer A. Primary lumbar vertebral hydatid cyst. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:472–473. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Güney O, Acar O, Kocaogullar Y. Echinococcus infestation of the splenius capitis. Br J Neurosurg. 2001;15:74–75. doi: 10.1080/02688690020024418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramos JM, Masia M, Padilla S, Bernal E, Martin-Hidalgo A, Gutiérrez F. Fatal infection due to larval cysts of cestodes (neurocysticercosis and hydatid disease) in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected patients in Spain: report of two cases. Scand J Infect Dis. 2007;39:719–723. doi: 10.1080/00365540701242392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dudkiewicz I, Salai M, Apter S. Hydatid cyst presenting as a soft-tissue thigh mass in a child. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1999;119:474–475. doi: 10.1007/s004020050025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomori JM, Cohen D, Eyd A, Pomeranz S. Water-lily sign in CT of cerebral hydatid disease: a case report. Neuroradiology. 1988;30:358. doi: 10.1007/BF00328190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malde HM, Gadkari SS, Chadha D, Gondhalekar N. Water-lily sign in an orbital hydatid cyst. J Clin Ultrasound. 1993;21:458–459. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870210709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Sayed M, Al-Mousa M, Al-Salem AH. A hydatid cyst at an unusual site. Trop Geogr Med. 1992;44:275–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beggs I. The radiology of hydatid disease. AJR. 1985;145:639–648. doi: 10.2214/ajr.145.3.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahniya MH, Hanna RM, Ashebu S, Muhtaseb SA, et al. The imaging appearances of hydatid disease at some unusual sites. Br J Radiol. 2001;74:283–289. doi: 10.1259/bjr.74.879.740283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Diez AI, Ros Mendoza LH, Villacampa VM, Cozar M, Fuertes MI. MRI evaluation of soft tissue hydatid disease. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:462–466. doi: 10.1007/s003300050077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haliloglu M, Saatci I, Akhan O, Ozmen MN, Besim A. Spectrum of imaging findings in pediatric hydatid disease. AJR. 1997;169:1627–1631. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.6.9393178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tarhan NC, Tuncay IC, Barutcu O, Demirors H, Agildere AM. Unusual presentation of an infected primary hydatid cyst of biceps femoris muscle. Skelet Radiol. 2002;31:608–611. doi: 10.1007/s00256-002-0524-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tatari H, Baran O, Sanlidag T, Gore O, Ak D, Manisali M. Primary intramuscular hydatidosis of supraspinatus muscle. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2001;121:93–94. doi: 10.1007/PL00013775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mezioug D, Touil-Boukoffa C. Cytokine profile in human hydatidosis: possible role in the immunosurveillance of patients infected with Echinococcus granulosus. Parasite. 2009;16:57–64. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2009161057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang W, Ross AG, McManus DP. Mechanisms of immunity in hydatid disease: implications for vaccine development. J Immunol. 2008;181:6679–6685. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sailer M, Soelder B, Allerberger F, Zaknun D, Feichtinger H, Gottstein B. Alveolar echinococcosis of the liver in a six-year-old girl with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Pediatr. 1997;130:320–323. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(97)70364-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]