Abstract

Adult cases with isolated juvenile xanthogranuloma of the central nervous system are very rare. We report a case with dumbbell-type juvenile xanthogranuloma in the cervical spine. A 38-year-old man presented with moderate numbness of the right ring finger and right little finger and weakness of the right grip. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an intra-spinal mass extending into the paravertebral area. The spinal cord was compressed by the lesion, which was isointense with the spinal cord on both T1- and T2-weighted imaging. Homogenous enhancement was observed after gadolinium administration. These findings favored a preoperative diagnosis of a rare tumor, rather than tumor of the nervous system. Complete surgical removal of the tumor was performed through hemilaminectomy combined with facetectomy between C7 and T1. Histological examination and immunohistochemical testing led to a diagnosis of juvenile xanthogranuloma. Two years after complete resection, MRI showed no recurrence. This appears to represent the first report of dumbbell-type juvenile xanthogranuloma in the cervical spine. Total removal of such lesions is recommended because of the high potential risk of tumor recurrence around the central nervous system.

Keywords: Cervical spine, Dumbbell-shaped tumor, Juvenile xanthogranuloma

Introduction

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) is a proliferative disorder of non-Langerhans histiocytes of the skin, occurring most often in infancy [4, 19, 20], although isolated JXG in the spinal column is extremely rare [5]. No cases of dumbbell-type JXG have been reported in the English literature. We report an adult case in a 38-year-old man.

Case report

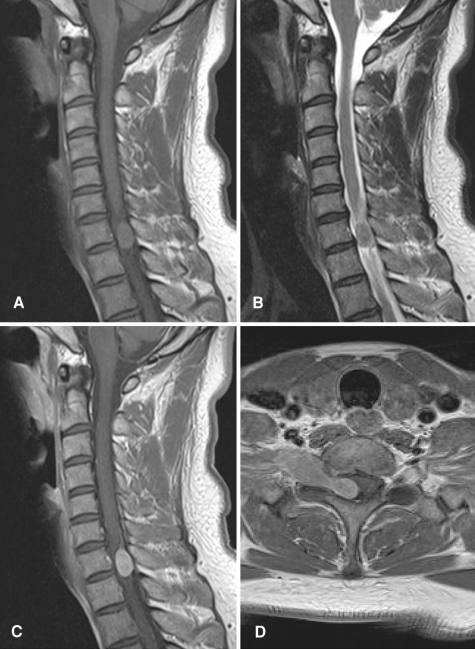

A 38-year-old man with no relevant past or family history was admitted to our hospital. Numbness of the right ring and little fingers had developed over a 3-month period, followed by weakness of the right grip and difficulty in running. The right hand showed muscular atrophy, but reflexes of the upper and lower extremities were all normal. Cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium contrast ruled out any cerebral lesions as a possible cause. Cervical MRI showed a dumbbell-shaped mass at the C7 level (Fig. 1). The spinal cord was compressed by the lesion, which was isointense with the spinal cord on both T1- and T2-weighted imaging. Homogenous enhancement was observed after gadolinium administration. These findings favored a preoperative diagnosis of rare tumor, rather than tumors of the nervous system.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative MRI. Sagittal T1- (a) and T2-weighted imaging (b) demonstrate an isointense lesion in the spinal canal. T1-weighted sagittal (c) and axial (d) views with gadolinium enhancement demonstrated a homogeneously enhanced dumbbell-shaped lesion

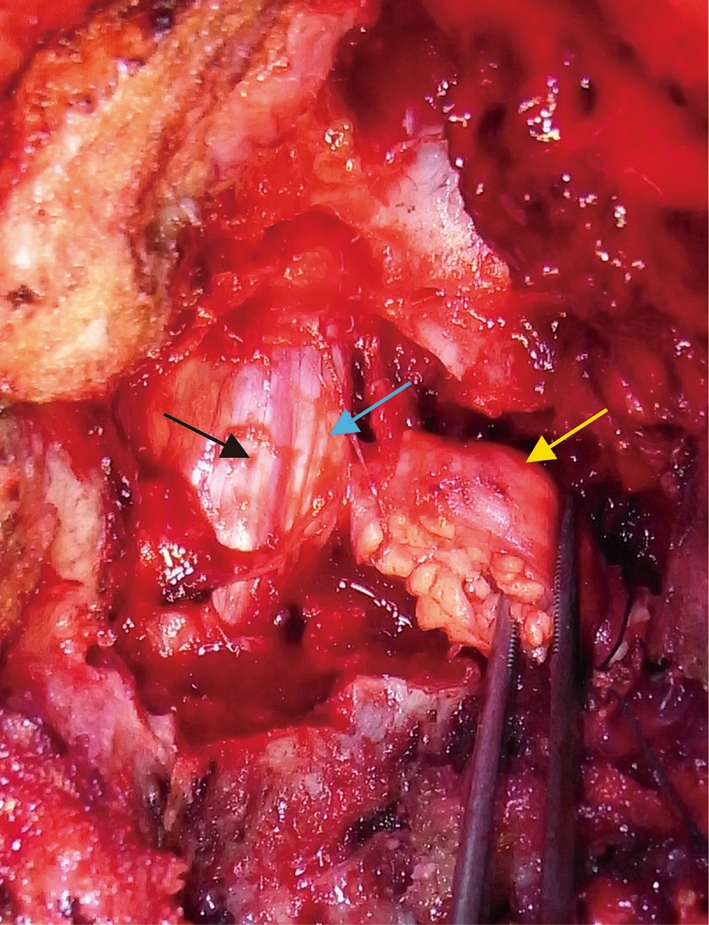

We performed hemilaminectomy from C7 to T1 with facetectomy between C7 and T1. A yellowish, encapsulated lesion was located in both intra- and extradural areas, extending to the paravertebral area (Fig. 2). The right C8 nerve root was involved by the mass. As we could not separate the root from the mass, we transected anterior and posterior roots proximal to the tumor in the intradural area and distal to the most lateral part of the tumor. The tumor was resected en bloc and the nerve root was sacrificed. Vascularity of the tumor was not rich.

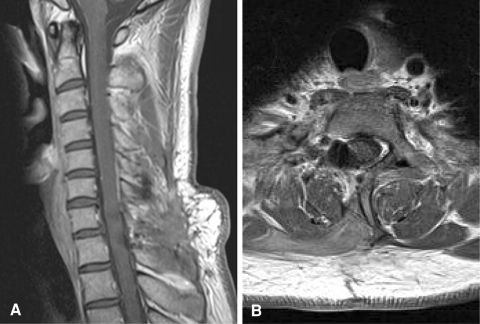

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative image showing an extradural component of the tumor extending to the paravertebral area (yellow arrow), intradural component (blue arrow) and the spinal cord (black arrow)

After surgery, numbness of the right ring and little fingers was slightly exacerbated, and right grip strength was slightly decreased. However, these symptoms gradually improved and the patient was asymptomatic by 2 years after surgery. Cervical MRI with gadolinium enhancement at 2 years after surgery demonstrated no residual or recurrent lesion (Fig. 3). We did not perform any instrumented stabilization, but no deformity was apparent at the cervicothoracic junction after laminectomy and facetectomy for the tumor.

Fig. 3.

Postoperative MRI from sagittal (a) and axial (b) views at 2 years after surgery, showing no residual or recurrent tumor

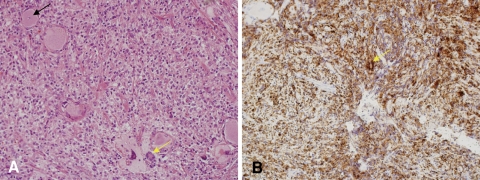

Histological examination of the tumor showed a xanthic appearance, with Touton giant cells (Fig. 4a). The specimen was subjected to immunohistochemical testing, yielding negative results for KL-1, desmin, ALK-1, EMA, CD34, and glial fibrillary acidic protein. Tumor cells were negative for S-100 protein, but large tumor cells proved intensely positive for CD68 (Fig. 4b, arrow). These findings confirmed a diagnosis of juvenile xanthogranuloma.

Fig. 4.

Histology of the tumor. a Touton giant cells (yellow arrow) and a ganglion cell (black arrow) are shown (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×200). b Large cells following CD68 staining. Bar 50 μm

Discussion

JXG is a benign disorder of the macrophage lineage that usually occurs in the dermis [21]. JXG typically appears as cutaneous lesions of the head and neck in children. Extracutaneous manifestations are uncommon. The incidence of JXG developing in soft tissues and other organs is 5% [5]. The eye, particularly the uveal tract, is the most frequent site of extracutaneous involvement, and other affected organs include the oropharynx, heart, lung, liver, spleen, adrenal glands, muscles, subcutaneous tissues, and the central nervous system (CNS), although involvement of the CNS in cases of cutaneous and/or extracutaneous JXG is rare [6, 16]. Isolated JXG involving the spinal column is extremely rare. We were able to identify only seven cases of intraspinal JXG reported in English [1, 2, 7–10, 16, 18] and no reports of dumbbell-type xanthogranuloma. In all except two reported cases, intraspinal JXG arose in infancy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cases of solitary juvenile xanthogranuloma involving the spine reported in the literature

| Case | Author | Year | Age | Sex | Location | MRI scans | Surgical resection | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | Gd | |||||||

| 1 | Shimosawa | 1993 | 13 months | F | Intradural extramedullary T6–T9 | Low | Low | No | Total |

| 2 | Kitchen | 1995 | 14 years | F | S1 nerve root | Iso | High | – | Total |

| 3 | Kim | 1996 | 16 months | M | Intradural extramedullary T1–T2 | Iso | High | Homo | Total |

| 4 | Rampini | 2001 | 34 months | F | Intradural extramedullary C5–C7 | Iso | Iso | Homo | Total |

| 5 | Iwasaki | 2001 | 14 years | M | Cauda equine | – | – | Hyper | Biopsy + steroid, vinblastine |

| 6 | Cao | 2008 | 18 years | F | C2 nerve root | Iso | Iso | Hyper | Total |

| 7 | Castro-Gago | 2009 | 41 years | M | Cauda equine | Iso | – | Homo | Partial resection + steroid |

| 8 | Inoue | Present | 38 years | M | C8 nerve root | Iso | Iso | Homo | Total |

High high intensity, Iso isointensity, Low low intensity, Gd gadolinium, Homo homogeneous, Hyper hyperintense

MRI is the best method for obtaining details of tumor localization and relationships to adjacent structures. Spinal JXG almost always appears isointense on T1-weighted imaging and hyper- or isointense on T2-weighted imaging, and homogeneous enhancement with gadolinium was observed in most reported cases (Table 1). However, a few JXG have been reported as hypointense on T2-weighted imaging [11, 18]. Such relatively low-intensity signals on T2-weighted imaging have been considered to reflect the poor cellular elements of the mass [11, 18]. When a similar signal pattern is observed on MRI, the histopathological differential diagnosis includes fibroma, fibrous meningioma, and solitary fibrous tumor. Intraoperatively distinguishing between JXG and other tumors of neural origin is difficult, and lesions such as schwannoma, neurofibroma, nerve sheath myxoma, malignant nerve sheath tumor, and solitary fibrous tumor must be considered. Histopathological and immunohistochemical methods remain the gold standard for diagnosing JXG. The tumor is typically a round lesion with a yellowish to grayish appearance on the cut surface. Microscopically, a diffuse and/or nodular pattern of growth and a pushing border are apparent at low magnification. The typical cellular composition of the lesions consists of one or more of the three basic cellular types: mononuclear cells; multinucleated cells with or without Touton features; and spindle cells. When present, the characteristic Touton giant cells can be found against a background of mononuclear cells. Immunohistochemical analysis has an important role to play in the diagnosis of JXG. The vast majority of JXGs studied have exhibited a fascin+, CD68+, HLA-DR+, LCA+, factor XIIIa+ phenotype, and S-100 protein is non-reactive in most cases [11, 14, 15]. These findings were compatible with this case and established the final diagnosis.

Previous results have indicated that total removal of JXG seems curative [16]. Dumbbell cervical tumors are often difficult to separate from spinal nerves. Complete removal is the ideal procedure to prevent recurrence, if this can be obtained with as little sacrifice as possible. According to previous reports, the risk of neurological deficit after transection of the nerve root for resection of dumbbell cervical tumor is low [3, 8, 12, 17]. In the present case, total resection was achieved and transient neurological deficit gradually recovered. Surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy or combinations of these modalities have all been used to treat CNS JXG. Stereotactic radiosurgery for CNS JXG is also reportedly effective [13]. Patients with systemic JXG including a CNS lesion are candidates for systemic chemotherapy. No standard treatment has been defined for solitary spinal JXG, and no long-term follow-up of spinal JXG has been reported, but total removal of the lesion has been recommended because of the high potential risk of recurrence [1, 16].

Conflict of interest

The authors do not report any conflicts of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper. No financial or material support was received for this work.

References

- 1.Cao D, Ma J, Yang X, Xiao J. Solitary juvenile xanthogranuloma in the upper cervical spine: case report and review of the literatures. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:S318–S323. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0606-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castro-Gago M, Gomez-Lado C, Alvez F, Alonso A, Vieites B. Juvenile xanthogranuloma of the cauda equina. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;40:123–125. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Celli P. Treatment of relevant nerve roots involved in nerve sheath tumors: removal or preservation? Neurosurgery. 2002;51:684–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen BA, Hood A. Xanthogranuloma: report on clinical and histologic findings in 64 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 1989;6:262–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1989.tb00909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graaf JH, Timens W, Tamminga RY, Molenaar WM. Deep juvenile xanthogranuloma: a lesion related to dermal indeterminate cells. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:905–910. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90403-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freyer DR, Kennedy R, Bostrom BC, Kohut G, dehner LP. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: forms of systemic disease and their clinical implications. J Pediatr. 1996;129:227–237. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(96)70247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iwasaki Y, Hida K, Nagashima K. Cauda equina xanthogranulomatosis. Br J Neurosurg. 2001;15:72–73. doi: 10.1080/02688690020024409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jian L, Lv Y, Liu XG, Ma QJ, Wei F, Dang GT, Liu ZJ. Results of surgical treatment of cervical dumbbell tumors. Spine. 2009;34:1307–1314. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a27a32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim DS, Kim TS, Choi JU. Intradural extramedullary xanthoma of the spine: a rare lesion arising from the dura mater of the spine: case report. Neurosurgery. 1996;39:182–185. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199607000-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitchen ND, Davies MS, Taylor W. Juvenile xanthogranuloma of nerve root origin. Br J Neurosurg. 1995;9:233–237. doi: 10.1080/02688699550041629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lesniak MS, Viglione MP, Weingart J. Multicentric parenchymal xanthogranuloma in a child: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:1493–1498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miura T, Nakamura K, Tanaka H, Kawaguchi H, Takeshita K, Kurokawa T. Resection of cervical spinal neurinoma including affected nerve root. Acta Orthop Scand. 1998;69:280–282. doi: 10.3109/17453679809000930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakasu S, Tsuji A, Fuse I, Hirai H. Intracranial solitary juvenile xanthogranuloma successfully treated with stereotactic radiosurgery. J Neurooncol. 2007;84:99–102. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9351-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nascimento AG. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical comparative study of cutaneous and intramuscular forms of juvenile xanthogranuloma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:645–652. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199706000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newman CC, Raimer SS, Sanchez RL. Nonlipidized juvenile xanthogranuloma: a histologic and immunohistochemical study. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:98–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1997.tb00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rampini PM, Alimehmeti RH, Egidi MG, Zavanone ML, Bauer D, Fossali E, Villani RM. Isolated cervical juvenile xanthogranuloma in childhood. Spine. 2001;26:1392–1395. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200106150-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Safavi-Abbasi S, Senoglu M, Theodore N, Workman RK, Gharabaghi A, Feiz-Erfan I, Spetzler RF, Sonntag VKH (2008) J Neurosurg Spine 9:40–47. doi: 10.3171/SPI/2008/9/7/040 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Shimosawa S, Tohyama K, Shibayama M, Takeuchi H, Hirota T. Spinal xanthogranuloma in a child: case report. Surg Neurol. 1993;39:138–142. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(93)90092-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sonoda T, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. Clinicopathologic analysis and immunohistochemical study of 57 patients. Cancer. 1985;56:2280–2286. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19851101)56:9<2280::AID-CNCR2820560923>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tahan SR, Pastel-Levy C, Bhan AK, Mihm MC. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. Clinical and pathologic characterization. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1989;113:1057–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zelger B, Cerio R, Orchard G, Wilson-Jones E. Juvenile and adult xanthogranuloma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:126–135. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199402000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]