Abstract

Only eight cases of intraosseous schwannoma of the mobile spine have been reported in the English literature. We report herein a rare case of intraosseous schwannoma mimicking benign osteoblastoma originating from the posterior column of the thoracic spine. A 60-year-old man presented with a history of back pain for several months. The patient subsequently developed gait disturbance and numbness on bilateral lower limbs. Preoperative computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging showed a neoplastic lesion occupying the posterior column of the ninth thoracic vertebra. The most likely preoperative diagnosis was osteoblastoma. The patient underwent tumor excision and posterior fusion with instrumentation. No nerve involvement of the tumor was identified intraoperatively. Histological diagnosis was schwannoma. To the best of our knowledge, this represents the first report of intraosseous schwannoma originating from the posterior column of the mobile spine.

Keywords: Magnetic resonance imaging, Intraosseous schwannoma, Osteoblastoma, Thoracic spine

Introduction

Intraosseous schwannomas (neurilemmomas) are rare benign neoplasms that account for <0.2% of primary bone tumors [5, 11]. Except for the long bones, the most common site of involvement is the mandible, and only eight cases involving the mobile spine have been described in the English literature [1–4, 8–10, 12]. All of these cases originated from vertebrae. To the best of our knowledge, intraosseous schwannoma originating from the posterior column of the mobile spine has not been reported. We report herein a case of intraosseous schwannoma originating from the posterior column of the thoracic spine and mimicking osteoblastoma on preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Case report

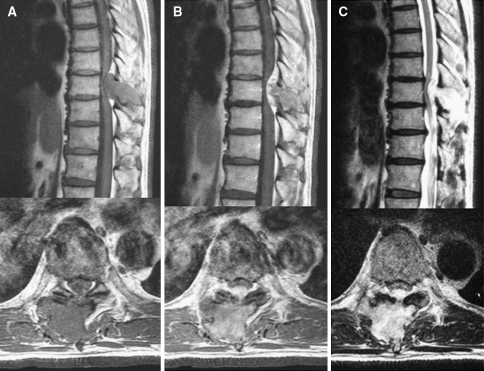

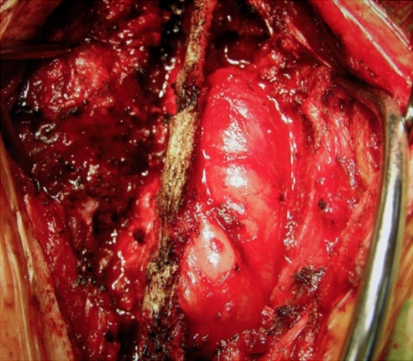

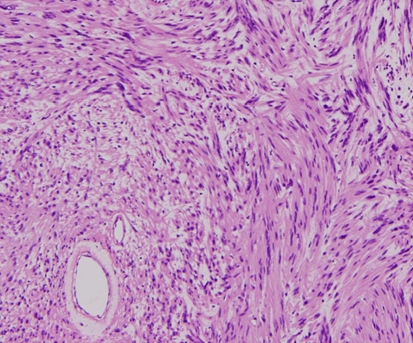

A 60-year-old man presented with a history of back pain for several months. The patient subsequently experienced progressive weakness of the lower extremities, gait disturbance and numbness on bilateral lower extremities. On admission, motor power was bilaterally graded as 4/5 for the hip flexors and knee extensors. Knee and ankle jerk were exaggerated. Preoperative computed tomography (CT) showed a large lytic lesion occupying the posterior column of T9, with erosion of the lamina and spinous process (Fig. 1). MRI showed a large mass extending into the paravertebral muscles and spinal canal (Fig. 2). The spinal cord was severely compressed by the lesion, which was isointense compared with the spinal cord on T1-weighted imaging and showed high mixed intensity on T2-weighted imaging. Irregular enhancement was observed after gadolinium administration. The most likely preoperative diagnosis according to radiologists in our hospital was a slowly growing tumor with bony erosion such as osteoblastoma arising within T9 posterior elements. Under this diagnosis, we planned en-bloc resection of the tumor and reconstruction using pedicle screw fixation as piecemeal resection of osteoblastoma would increase the risk of recurrence. Using a posterior approach, the tumor was found to be well demarcated and extending into paravertebral areas and the spinal canal (Fig. 3). After removal of the residual lamina and facet joints, the tumor was removed whole, and the spine was stabilized with pedicle screws and rods. No adhesions were identified between the dura mater and tumor. No involvement of nerves with the tumor was identified. Histological examination of the tumor showed a compact cellular area with spindle-shaped cells showing palisading of nuclei, i.e., Verocay bodies (Antoni type A tissue) with areas of less cellular myxoid connective tissue (Antoni type B tissue) (Fig. 4). Histological results confirmed a diagnosis of intraosseous schwannoma with no remnants of an originating nerve. Postoperative MRI showed spinal cord decompression (Fig. 5). Postoperatively, gait and sensation in the lower extremities showed good recovery. Follow-up MRI at 2 years postoperatively showed no recurrence.

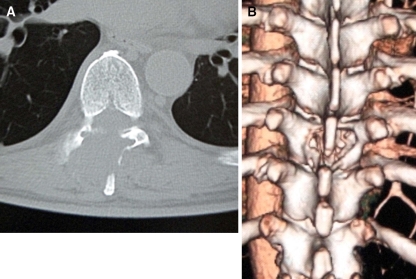

Fig. 1.

Preoperative computed tomography (CT) showing a lytic defect with extensive cortical erosion of the posterior column of T9: a axial view, b three-dimensional CT image

Fig. 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The tumor mass occupies the posterior column of T9 with spinal cord compression and paravertebral muscle extension. a T1-weighted imaging. The tumor is isointense compared with the spinal cord. b Gd-enhanced T1-weighted imaging showing irregular enhancement. c T2-weighted imaging. The tumor shows high mixed intensity compared with the spinal cord

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative image. The tumor is extending outside the lamina and spinous process of T9

Fig. 4.

Histological features showing a compact cellular area with spindle-shaped cells, palisading of nuclei representing Verocay bodies (Antoni type A tissue) with areas of less cellular myxoid connective tissue (Antoni type B tissue), indicating a typical schwannoma (hematoxylin and eosin stain; ×100)

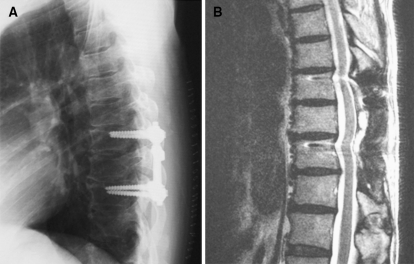

Fig. 5.

Postoperative radiography and MRI: a reconstruction using pedicle screws, b T2-weighted MRI 2 years after surgery showing no recurrence

Discussion

Schwannomas usually involve bone through three possible mechanisms: extraosseous tumor causing erosion of the bone; tumor arising within the nerve canal and growing in a dumbbell-shaped configuration producing enlargement of the canal; or tumor arising centrally within bone [6]. True “intraosseous schwannoma” has been defined as an intraosseous tumor with or without extraosseous components and no neural tissue involvement with the tumor [2]. The infrequent occurrence of intraosseous schwannomas has been attributed to a paucity of sensory fibers in the bones although the presence of myelinated fibers within the marrow of the vertebral bodies has been reported [13].

A total of 8 cases with intraosseous schwannoma in the mobile spine have been described in the English literature: 4 in the cervical spine; 2 in the thoracic spine; and 2 in the lumbar spine [1–4, 8–10, 12]. In all these published cases, tumors originated from the vertebrae. No previous reports have described intraosseous schwannoma originating from the posterior column of the mobile spine.

Preoperative MRI and CT showed an appearance compatible with osteoblastoma. A sharply defined, expansile lytic lesion of the posterior elements of the mobile spine is an typical imaging finding for spinal osteoblastoma. For en-bloc resection, preoperative pathological diagnosis is crucial and mandatory to make appropriate surgical plan. If we had recognized the possibility of schwannoma, we have might considered marginal or piecemeal resection without facetectomy or instrumentation. However, because this intraosseous schwannoma had small niches in bilateral facet joints in the CT axial view (Fig. 1a), facetectomy and instrumentation can be justified for this case. Preserving facet joints to save stability might lead to local recurrence of intraosseous schwannoma [7].

To exclude well-demarcated bony tumors arising from an unusual location in the spine, preoperative or intraoperative biopsy should be performed to know actual pathology and select an appropriate treatment option. Intraosseous schwannoma is very rare, but can be included in the differential diagnosis for expansile lesions involving posterior elements of the mobile spine.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors do not report any conflicts of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper. No financial or material support was received for this work.

References

- 1.Bart Schreuder HW, Veth RPH, Pruszczynski M, Lemmens JAM, Vanlaarhoven EW. Intraosseous schwannoma (neurilemmoma) of the cervical spine. Sarcoma. 2001;5:101–103. doi: 10.1155/S1357714X01000196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang CJ, Huang JS, Wang YC, Huang SH. Intraosseous schwannoma of the fourth lumbar vertebra: a case report. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:1219–1222. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199811000-00120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choudry Q, Younis F, Smith RB. Intraosseous schwannoma of D12 thoracic vertebra: diagnosis and surgical management with 5-year follow up. Eur Spine. 2007;J16:S283–S286. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0247-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickson JH, Waltz TA, Fechner RE. Intraosseous neurilemoma of the third lumbar vertebra. J Bone Joint Surg. 1971;53:349–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fawcett KJ, Dahlin DC. Neurilemmoma of bone. Am J Clin Pathol. 1976;47:759–766. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/47.6.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon EJ. Solitary intraosseous neurilemmoma of the tibia. Clin Orthop. 1976;117:271–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang L, Lv Y, Liu XG, Ma QJ, Wei F, Dang GT, Liu ZJ. Results of surgical treatment of cervical dumbbell tumors. Surgical approach and development of an anatomic classification system. Spine. 2009;34:1214–1307. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a27a32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naidu MR, Dinakar I, Rao K, Ratnakar KS. Intraosseous schwannoma of the cervical spine associated with skeletal fluorosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1988;90:257–260. doi: 10.1016/0303-8467(88)90033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nannapaneni R, Sinar EJ. Intraosseous schwannoma of cervical spine. Br J Neurosurg. 2005;19:244–264. doi: 10.1080/02688690500207546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nooraie N, Taghipour M, Arasteh MM, Daneshbod K, Erfanie MA. Intraosseous schwannoma of T12 with burst fracture of L1. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1997;116:440–442. doi: 10.1007/BF00434011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palocaren T, Walter NM, Madhuri V, Gibikote S. Schwannoma of the fibula. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:803–805. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B6.19901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polkey CE. Intraosseous neurilemmoma of the cervical spine causing paraparesis and treated by resection and grafting. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1975;38:776–781. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.38.8.776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sherman MS. The nerve of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1963;45:522–528. [Google Scholar]