Abstract

Gluteal compartment syndrome (GCS) is an extremely rare and potentially devasting disorder, most commonly caused by gluteal muscle compression in extend periods of immobilization. We report a 65-year-old obese man with hypertension, diabetes mellitus type 2 and hypercholesterolemia underwent lumbar spine surgery in knee-chest position because of degenerative lumbar stenosis. Perioperative hypotension occurred. After surgery, the patient developed increasing pain in the buttocks of both sides and oliguria with darkened urine. Stiffness, tenderness and painful swelling of patients gluteal muscles of both sides, high creatine phosphokinase level, myoglobulinuria and oliguria led to diagnosis of bilateral GCS, complicated by severe rhabdomyolysis (RM) and acute renal failure. In conclusion, obese patients with vascular risk factors and perioperative hypotension may be at risk for developing bilateral GCS and RM when performing prolonged lumbar spine surgery. Early diagnosis and treatment is important, as otherwise, the further course may be fatal.

Keywords: Gluteal compartment syndrome, Kidney failure, Lumbar spine, Neurosurgery, Rhabdomyolysis

Introduction

Compartment syndrome (CS) is characterized by increased intracompartmental pressure and may lead to reduced blood flow and perfusion deficit of the involved muscles and nerves. A severe complication of CS is rhabdomyolysis (RM) and acute renal failure. Clinically, generalized malaise, nausea, muscle weakness, tenderness, stiffness, and darkened urine are typical symptoms [9].

Gluteal CS (GCS) is an extremely rare condition and potentially devasting. The clinical picture may range from sciatic nerve palsy to massive RM, acute renal failure, multiple organ failure, and death [2, 5, 10]. The most common cause is gluteal muscle compression under prolonged immobilization, due to substance abuse or trauma.

In a surgical setting, the lithotomy-, sitting- and lateral decubitus position of obese patients may lead to GCS in extend periods of immobilization [8]. However, it was shown that GCS may be related to vascular hypoperfusion as well [7]. To the best of our knowledge, GCS associated with the knee-chest position in spinal lumbar surgery has not been reported so far.

We report the first case of spinal lumbar surgery, complicated by bilateral GCS and severe RM and discuss causes and clinical implications.

Case report

We report a 65-year-old obese man (height 178 cm, weight 124 kg, BMI 39.1) with a previous medical history of diabetes mellitus (DM) type 2, treated by subcutaneous insulin applications. Secondary complications to DM were a mild retinopathy and nephropathy and a polyneuropathy (PN). The PN had a symmetrical sensory distribution below the knees; ankle reflexes were absent. Additionally, he was treated for a long-standing hypertension with enalaprilmaleate/hydrochlorothiazide, amliodipine and metoprolol. Furthermore, hypercholesterolemia was treated with simvastatine for several years prior to surgery. The patient did not report muscular complications after starting with simvastatine. Otherwise, he was healthy. Further physical and neurological examination was normal. Indication for bilateral decompression L3–L5 were long-lasting recurrent painful sensory radicular symptoms in both legs, compatible with the radiological findings of a degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis at L3/L4 with involvement of both L4 roots, and foraminal recess stenosis at L5 and S1 with compression of the left L5 and S1 root.

Preoperative fasting glucose was 8.2 mmol/l, other laboratory results were normal. After endotracheal anesthesia with curacite 100 mg, thiophentale 500 mg and fentanyle 0.3 mg, the patient was placed in a knee-chest position on a standard operation table with a large cushion under the thorax, about 100° flexion in the hips and 80° flexion in the knees. Additionally a cushioned bar supporting the buttocks and soft side supports against the femoral trochanters were used to stabilize the position. The patient mainly rested on the knees, ischiadic tubercles, thorax and to a lesser extent on abducted and flexed arms. However, a slight compression of his obese abdomen on the operation table could not be avoided. The position was ensured by the surgeons and was not changed during surgery other than some intermittent sideways rotation. Due to high tone in the lumbar spine extensor muscles, vecuronium was given shortly after incision. Laminectomy at the levels L3, L4 and L5 and selective microsurgical decompression of the corresponding nerve root foramina was performed. Finally, the recessed bone tissue was placed in decorticated grooves, bridging the facet joints to achieve spondylodesis. Operation time was 4 h. Perioperative monitoring included routine anesthesia monitors, blood pressure (BP) cuff, oxymetry, capnography, urine output and electrocardiogram. An intra-arterial catheter was placed for blood gas measurements. After closure, slight erythema over both trochanter regions but not the buttocks was noted.

Forty minutes after surgery onset, hypotension was noted with a BP-fall from 140/80 to 80/50 mmHg, probably a side effect of patients anesthetic medications. After giving loads of colloid fluids (totally 3,500 ml during surgery), the BP could be stabilized at 115/80 mmHg about 30 min after hypotension onset until the end of surgery. There were normal perioperative values for blood gasses, arterial O2 and CO2 and total diuresis was 300 ml, with normal color.

In the first 2 h after surgery, the patient was alert and hemodynamically and respiratory stable on the postoperative care unit. Local muscle compression, erytema and swelling were not noted. Blood glucose was 12.9 mmol/l. However, he complained about some diffuse pain in the back and the buttocks which was thought to be related to postoperative back pain. Seven hours after surgery, the pain in the buttocks had increased and oliguria with darkened urine was noted. At examination severe stiffness, tenderness and painful swelling of gluteal muscles of both sides, more on the left side, was found. Sciatic nerve palsy was absent. Laboratory examinations of blood samples revealed a creatine phosphokinase (CPK) level at 91,000 IU/l (normal 30–240 IU/l). The clinical diagnosis of a bilateral gluteal compartment syndrome (GCS) associated with acute rhabdomyolysis (RM) and acute kidney failure was made. Subsequently, the patient was referred to surgical decompression. A magnetic resonance (MR) scan after surgical decompression revealed extensive edema of all gluteus muscles on both sides, most on the left side (Fig. 1). Abnormalities of abdominal organs and vessels were not found. Despite early aggressive fluid replacement, forced diuresis and urine alkalinization, the urine output dropped to 30 ml/24 h postoperative. Therefore, the patient was referred to hemodialysis, resulting in dramatic improvement of the kidney function after five courses. However, the pain was unchanged. Opioid analgetics were introduced, resulting in moderate pain improvement. The patient then underwent physical mobilization by a physiotherapist, and 1 week after starting hemodialysis, he was able to go a few steps with support. Finally, the patient could be referred to a rehabilitation centre. At discharge, only slight kidney impairment was found, and he was mainly depended on wheelchair because of slight to moderate gluteal pain and bilateral insufficiency of the gluteal muscles.

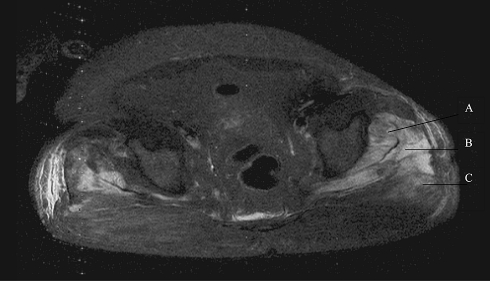

Fig. 1.

T1-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) image showing edema and swelling of the gluteus minimus (a), gluteus medius (b) and gluteus maximus muscle (c) of both sides, more extensive on the left side

Discussion

To our knowledge, we described the first patient with bilateral GCS and severe rhabdomyolysis (RM) as complication to lumbar spine surgery in knee-chest position.

GCS is an extremely rare condition, mostly related to gluteal muscle compression after altered consciousness levels and prolonged immobilization of obese patients whom undergo surgical treatment, particular in the lithotomy-, sitting- and lateral decubitus position [4, 8]. Our patient had a knee-chest position with only slight perioperative gluteal compression, making this etiology alone unlikely. It has been shown, that abdominal compression may be related to visceral hypoperfusion, particular in obese patients with prolonged operation time [1, 6, 12]. However, only slight abdominal compression was noted in this cause. Therefore, other causes have to be considered, despite patients obesity and prolonged operation time. Additionally, our patient had prolonged perioperative hypotension, probably related to his anesthetic medications. As comorbidity of hypertension, diabetes mellitus and hypercholesterolemia is associated with arteriosclerosis, hypotension probably contributed to pelvic hypoperfusion, bilateral gluteal muscle ischemia and GCS. This theory supports by a previous report, that bilateral GCS and RM may be related to visceral ischemia [7]. Furthermore, patients perioperative hip-flexion in knee-chest position probably disposed to higher gluteal intracompartmental pressure. Other risk factors for developing RM in our patient were use of simvastatine and diabetes mellitus [3]. However, the patient did not report statine related muscular complications for years prior to surgery and perioperative signs of ketoacidosis were absent, making these risk factors unlikely.

Early symptoms of GCS may be unspecific, including gluteal tenderness without evidence of sciatic neuropathy, as in our patient [7]. The further course may lead to development of bilateral gluteal stiffness, extreme pain with passive range of motion, darkened urine and oliguria, compatible with RM and acute kidney failure, as presented here [2]. Eight hours of muscle ischemia are generally fatal [11]. As the symptoms probable lasted between 7 and 11 h before the diagnosis was made, that would explain the severity of RM in this case. Therefore, it seems to be important to the neurosurgeon to have a high index of suspicion for this entity early in course to avoid serious complications.

The most important way for preventing GCS could be recognizing those patients at risk. As bilateral GCS is a very rare complication in lumbar spine surgery, a multifactorial etiology has to be taken into account. Because obese patients with vascular risk factors may be at risk for prolonged surgery time, it could be argued to operate in the prone position. However, in prone position, obese patients may be at risk for visceral hypoperfusion and GCS. Further studies could be performed to compare the risk of GCS in different surgical positions for lumbar spine surgery. Additionally, postoperative blood CPK examination might be useful in these patients to obtain this serious complication early in course.

In conclusion, elderly obese patients with vascular risk factors and prolonged perioperative hypotension may be at risk for developing bilateral GCS and rhabdomyolysis when performing prolonged lumbar neurosurgery in knee-chest position. Appropriate recognition and treatment is important, as otherwise, rhabdomyolysis may further exacerbate and may be devasting.

Conflict of interest statement

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Foster MR. Rhabdomyolysis in lumbar spine surgery. A case report. Spine. 2003;28:276–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill SL, Bianchi J. The gluteal compartment syndrome. Am Surg. 1997;63:823–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huerta-Alardín AL, Varon J, Marik PE. Bench-to-bedside review: rhabdomyolysis—an overview for clinicians. Crit Care. 2005;9:158–169. doi: 10.1186/cc2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krysa J, Lofthouse R, Kavanagh G. Gluteal compartment syndrome following posterior cruciate ligament repair. Injury. 2002;33:835–838. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(02)00092-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuklo TR, Tis JE, Moores LK, Schaefer RA. Fatal rhabdomyolysis with bilateral gluteal, thigh, and leg compartment syndrome after The Army Physical Fitness Test. A case report. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:112–116. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280010401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papadakis M, Sapkas G, Tzoutzopoulos A. A rare case of rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure following spinal surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9:387–389. doi: 10.3171/SPI.2008.9.10.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pua BB, Muhs BE, Cayne NS, Dobryansky M, Jacobowitz GR. Bilateral gluteal compartment syndrome after elective unilateral hypogastric artery ligation and revascularization of the contralateral hypogastric artery during open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:337–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rommel FM, Kabler RL, Mowad JJ. The crush syndrome: a complication of urological surgery. J Urol. 1986;135:809–811. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45863-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Visweswaran P, Guntupalli J. Rhabdomyolysis. Review Crit Care Clin. 1999;15:415–428. doi: 10.1016/S0749-0704(05)70061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshioka H. Gluteal compartment syndrome. A report of 4 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1992;63:347–349. doi: 10.3109/17453679209154800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitesides TE, Hirada H, Morimoto K. The response of skeletal muscle to temporary ischaemia: an experimental study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53A:1027–1028. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziser A, Friedhoff RJ, Rose SH. Prone position: visceral hypoperfusion and rhabdomyolysis. Anesth Analg. 1996;82:412–415. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199602000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]