Abstract

Pharyngoesophageal diverticulum after anterior cervical spine surgery is a rarely reported but potentially life-threatening complication. A case report of pharyngoesophageal diverticulum 7 years after anterior cervical spine surgery is presented. The patient suffered from dysphagia, odynophagia, recurrent fever, weight loss, and also an impressive bulging in the neck with swallowing. After careful examination and preparation, he underwent revision surgery via an open procedure, had the implants removed, pouch excised, and esophagus reconstructed reinforced by a sternohyoid muscle flap as well as an omohyoid muscle flap. The post-operative period was uneventful, and he experienced a satisfactory recovery. At last follow up, 2.5 years post surgery, the patient remained symptom free. Upon review of the literature, only six such previous reports with seven cases were found. Diagnostic tools, possible mechanism, correlative factors and treatment are discussed. This patient was fortunate that although his symptoms developed long after the initial anterior cervical operation and the pouch grew impressively large almost perforating, he still recovered well. It again proves the necessity of long-term X-ray follow up, and also reminds the surgeons to be alert of the possibility of esophageal injury even when the esophageal symptoms are mild and occur long after the initial operation.

Keywords: Pharyngoesophageal diverticulum, Anterior cervical spine surgery, Sternohyoid muscle flap, Omohyoid muscle flap, Complication

Introduction

Anterior cervical spine surgery is an established treatment for cervical spine disorders and trauma. Although the procedure is thought to be well-developed and surgeons are becoming more skillful using this technique, complications still arise. Injury of the pharynx and esophagus is one of the most serious complications and can lead to death. Pharyngoesophageal perforation after anterior cervical spine surgery is already well-documented [1–3], however, another type of esophageal complication, pharyngoesophageal diverticulum is not so well-recognized. It is an acquired pouch which is located proximally to the upper esophageal sphincter, usually on the posterior hypopharyngeal wall [4]. Pharyngoesophageal diverticulum is mostly found among elderly people who are in their 70s or 80s, and only a few authors have reported it as a much rarer complication of anterior spine surgery [5–10].

Here we present a patient who developed a large pharyngoesophageal diverticulum 7 years after anterior cervical spine surgery. The patient underwent a revision operation, had the implants removed, pouch excised and esophagus sutured. We also introduced the use of sternohyoid and omohyoid muscle flaps as a reinforcement of the primary repair, which proved to be successful after 2.5-year follow up. Previous literature on this type of diverticulum is also reviewed.

Case report

A 31-year-old man was involved in a car accident as a backseat passenger in June 2000. He complained of neck pain and numbness in his right leg. Neurological examination revealed sensory deficit in the right lower extremity. Plain X-rays showed fracture in the superior articular process of C5 on both sides and dislocation of C4/C5. After 3 months of conservative treatment his symptoms continued to worsen, he returned to his local hospital and received his first operation using a posterior wiring technique, and a second operation consisting of C5 corpectomy, autologous iliac bone graft fusion and fixation with plate and screws. The patient’s recuperation was satisfactory, and all of his symptoms resolved.

The patient enjoyed nearly 7 years free of any complaints until May 2007, when he began to feel mild but persistent dysphagia and episodes of odynophagia. Two months later he started to suffer a dry cough while recumbent. As his cough became increasingly intense, the patient also experienced a recurring fever. Following diagnosis at the local hospital, he was given antibiotic therapy for laryngopharyngitis. Although his recurrent fever resolved, his dysphagia grew in severity. In addition, he noticed that there was a bulge in his neck when swallowing (Fig. 1). By the time he was admitted to our hospital, he had already lost more than 5 kg of weight.

Fig. 1.

Photographs of the patient’s neck, showing the normal appearance, the obvious bulge when swallowing, and continued swelling 5 min later, respectively

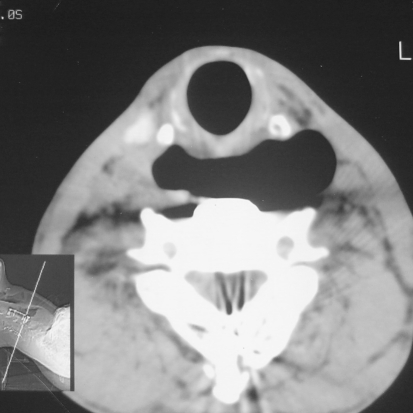

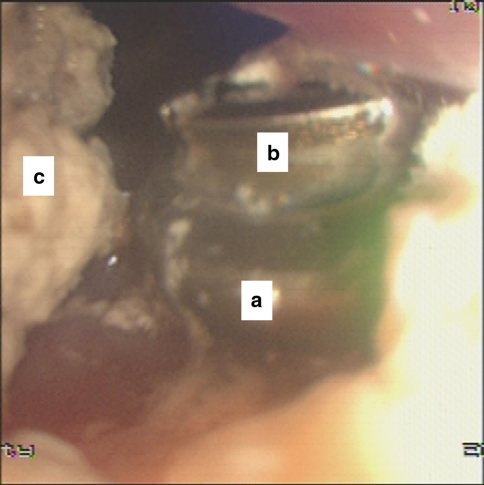

An X-ray of the patient’s cervical spine surprisingly depicted a ballooned esophagus full of gas and a mixture of food residue just below the hypopharynx, as well as vertebral bone absorption directly behind it. Barium swallow showed the contour of the pouch clearly (Fig. 2). The plate and screws, however, appeared properly located and without dislodgement. A CT scan revealed that his esophagus had extended into a large airspace in front of the vertebral body and in several places just surrounding the plate and screws. The plate seemed to have penetrated into the esophagus (Fig. 3); however, the patient was afebrile and showed no symptoms of mediastinitis. Flexible endoscopy revealed a large cavity just below the hypopharynx. The plate and screws were also found to be protruding into the proximal esophagus (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Barium swallow demonstrating the large pouch in the esophagus

Fig. 3.

CT scan shows a large airspace and the plate appearing to have penetrated the esophagus

Fig. 4.

Endoscopic photographs. Upon careful examination, we found the edge of the plate “a” and a screw “b” in a corner of the pouch. “c” shows the remaining barium after the barium swallow the previous day

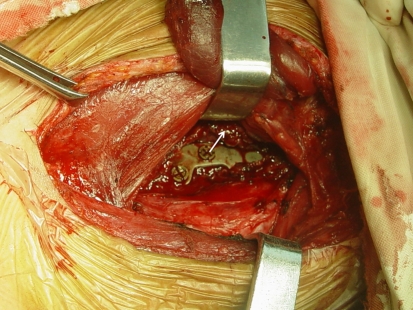

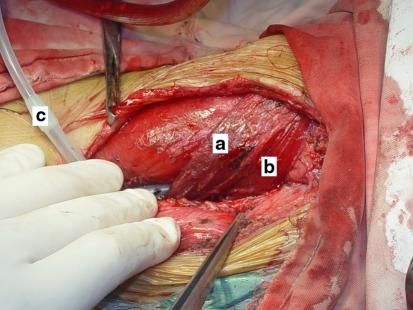

The revision surgery was performed with a team approach in close coordination with spine surgeons, otolaryngology surgeons and thoracic surgeons. At the time of operation the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle was found to be incomplete, and a large pouch bulged out from the posterior wall of the esophagus. There was also a large defect on the posterior wall of the pouch, covered by thin layers of epithelial cells (Fig. 5). After releasing the adhered part of the esophagus from the vertebra and the plate, we removed the plate and screws, excised the pouch, and reconstructed the esophagus with interrupted suture. Sternohyoid and omohyoid muscle flaps were used to reinforce the primary repair (Fig. 6). The post-operative period was uneventful and the patient reported much easier swallowing and no other complaints, and was discharged on the 15th day. Upon the latest follow up 2.5 years post operation, the patient remained in good condition with no further complications.

Fig. 5.

Intraoperative picture showing the implants and arrow indicating the edge of the nearly ruptured esophagus

Fig. 6.

Having finished the repair reinforced by the muscle flaps. a sternohyoid muscle flap, b omohyoid muscle flap, c suction drain

Discussion

Pharyngoesophageal injuries after anterior cervical spine surgery are a type of rare but noteworthy complications because of their potentially disastrous outcome. Among all kinds of esophageal injuries related to anterior cervical spine surgery, pharyngoesophageal diverticulum is the most unusual, with only seven cases reported by six previous authors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Literature review of pharyngoesophageal diverticulum following anterior cervical spine surgery

| Reference | Age (year) | Sex | Indication | Level | Number of operations | Operation | Location | Graft or implant dislodgment | Postoperative development | Symptoms | Speculated cause | Treatment | Outcome/follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goffart et al. [10] | 44 | M | Trauma | C6–C7 | 2 | AF without IF | Posterior | Yes | 8 months | Dysphagia, regurgitation weight loss | Scar adherence | OS, DE, ER with facia lata reinforcement | Symptom reduced, occasion sticking of food/18 months |

| Salam and Cable [5] | 36 | F | Degenerative disease | C5–C6 | 2 | AF without IF | Posterior | Yes | 3 years | Dysphagia | Adherence due to bone graft dislodgment | Dohlman’s endoscopic diathermy procedure | Symptom anesis/3 months |

| Sood et al. [8] | 45 | M | Trauma | C6 | 1 | AF + IF | Posterior | No | 13 years | Dysphagia | Scar adherence | OS, DE, ER | Symptom free |

| Ba et al. [6] | 28 | F | Trauma | C5–C6 | 1 | Fusion + IF | Posterior | No | ND | Regurgitation | Scar adherence | OS, DE, ER | Asymptom |

| Ba et al. [6] | 63 | M | ND | ND | 1 | Fusion + IF | Right lateral | No | 6 months | Dysphagia, regurgitation | Scar adherence | OS, DE, ER | Symptom free |

| Summers et al. [7] | 43 | F | Degenerative disease | C4–C7 | 1 | AF + IF | Posterior | Yes | 2 years | Dysphagia, odynophagia, intermittent fever, weight loss | Dislodged instrumentation | OS, DE, ER, RI | Died in recovery |

| Joanes and Belinchon [9] | 31 | M | Trauma | C5–C7 | 1 | AF + IF | Posterior | Malposition | 3 years | Dysphagia, regurgitation, cough, weight loss | Esophageal erosion by the hardware malposition | OS, DE, ER, RI | Asymptom/3 years |

| Our case | 31 | M | Trauma | C5 | 1 | AF + IF | Posterior | No | 7 years | Dysphagia, odynophagia, cough, weight loss | Scar tissue adherence and inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle absence | OS, DE, RI, ER with sternohyoid and omohyoid muscle reinforcement | Symptom free/2.5 years |

ND not described, AF allograft fusion, IF internal fixation, OS open surgery, DE diverticulum excision, ER esophagus repair, RI remove of implant

Pharyngoesophageal diverticulum, also termed Zenker’s diverticulum, is the most common type of diverticulum in the upper gastrointestinal tract. It is an acquired pouch which is located proximal to the upper esophageal sphincter, usually on the posterior hypopharyngeal wall. It is mostly found among those patients who are in their 70s or 80s, and rarely before the age of 40. Although there has been an attempt to reveal the pathogenesis of pharyngoesophageal diverticulum for a long time, it is still unclear. The most popular hypotheses is the malfunction of the cricopharyngeal muscles leading to outflow obstruction and creating a zone of high pressure in the hypopharynx, thus a diverticulum develops from Killian’s triangle, the inherent area of weakness on the esophageal wall [4].

Early recognition of pharyngoesophageal diverticulum seems to be difficult, because it is not as aggressive as an esophageal perforation, and can develop over a long period of time before it grows large enough to cause symptoms. However, after symptoms occur, the diagnosis should not be difficult. The most common clinical symptom is dysphagia, which was a complaint of most of the patients. Other complaints include regurgitation and odynophagia, while some patients also suffered from cough, fever and weight loss. Plain X-ray, CT scan, esophagography with contrast medium and endoscopy are all conventional methods. X-rays of the cervical spine can provide a preliminary impression of the esophagus by the prevertebral shadow and show the position of the implants. CT scan can demonstrate the shape of the pouch, and can also discover whether it is complicated by esophageal perforation [11]. Esophagography with contrast medium can obtain a clear view of the contour of the pouch as well as its position relative to the esophagus. Endoscopy gives the most clear and direct view, which is useful for surgery, but it is unwise to use this as the initial diagnostic tool [12]. For our case, we had already detected the diverticulum by esophagography and knew where it was located; nonetheless, it still required a significant amount of time by an experienced physician to find the lesion under endoscopy.

It is difficult to make a firm conclusion for the etiology of this case because it is really long time after the operation, and also might be a consequence of coactions of many factors. By reading the X-ray (Fig. 2), we may think the plate is not flush against the vertebral body (it might be partly resulted from the bone erosion by the huge pouch and scar tissue), and two of the screw heads were not flush inside the screw holes, but were sitting a little proudly in the plate. This could have facilitated a micro-traumatic effect on the esophagus and eventually caused this complication. However, most of the previous authors attribute the diverticulum formation to the adherence of the esophagus to the vertebral body and fixation system caused by dense scar tissue. We discovered the same adherence in our case, and this may have been the cause of the diverticulum formation. In addition to these, at the time of surgery, the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle was found to be incomplete, and it is possible that this may have been damaged in the first anterior cervical spine operation. As the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle plays an important role in the swallowing mechanism, this may have caused an outflow obstruction, creating a high pressure zone in the hypopharynx, eventually resulting in diverticulum formation. It is difficult to decide which was the main cause of the diverticulum formation, and they all probably played a part in the process.

Many authors attempted to evaluate other possible correlations between these patients, such as age, number of operations, and number of fusion levels [13]. We also tried to do this, but it is difficult to reach a firm conclusion for pharyngoesophageal diverticulum patients as we have only a small number of cases. Among the eight patients that have been reported, the average age was 40.1 which is relatively young when compared with the average age of patients who have undergone cervical spine surgery [14]. This may be due to the fact that five of them were trauma patients. The most frequently involved level was C5–C6. Indication for cervical spine surgery was either trauma or degenerative disease; however, there seems to be more trauma patients. Some authors have reported that many of their patients who suffered from esophageal complications had experienced two or more cervical spine operations [15–17]; however, among the eight pharyngoesophageal diverticulum patients, only two of them had a second cervical operation. Graft or implant dislodgment also does not seem necessary for pharyngoesophageal diverticulum, as four of the patients just had normal implant position.

There are many different choices for the treatment of pharyngoesophageal diverticulum, and among them, flexible endoscopic treatment has become more popular [4]. It is effective and safe, which is especially good for the high-risk patients who may not tolerate general anesthesia. However, for the patients whose diverticulum is considered to be a complication of anterior spine surgery, it is more complicated due to the factors such as implants and scar tissue which makes the endoscopic repair difficult [6]. In these cases, the best choice may be open diverticulectomy and repair. Generally, after excision of the diverticulum, the primary closure of the esophagus should be reinforced by soft tissue. The most popular technique used is to employ the sternocleidomastoid muscle flap [18–20], but the consequences of this are increasingly apparent, such as lack of a clearly defined arterial blood supply, late oral intake, restricted motion, deformity of the neck, and potential damage to the sensory nerves [21]. Some practitioners have tried using alternate muscle flaps, such as the pectoralis major flap [11], infrahyoid muscle flaps [22], and omental muscle flaps [23]. There have also been reports of esophageal reconstruction using a free jejunal loop [24]. We used both the sternohyoid muscle flap and omohyoid muscle flap, which has proved to be successful.

In our case, pharyngoesophageal complication occurred 7 years after the initial anterior cervical operation. This is significantly longer than all but one other reports in the literature. This was a chronic process, taking several years to progress, which allowed time for the epithelial cells to creep over the implants thus preventing serious fistula formation and infection. The pouch in our case was also impressively large when compared to other case reports. Despite the large diverticulum and nearly perforated esophageal wall, our patient enjoyed a successful revision surgery and an uneventful post-operative period. Besides meticulous surgical technique, careful planning and preparation are also critical for achieving successful results.

Conclusion

We have reported a rare but life-threatening complication of anterior cervical spine surgery. By open surgery including pouch excision and esophageal repair reinforced by a sternohyoid muscle flap and omohyoid muscle flap, we achieved an excellent result. Surgeons should always be alert of the possibility of esophageal injury related to cervical spine surgery especially when the patients have esophageal symptoms; even when these symptoms occur long after operation. Routine X-ray follow up and careful history taking is helpful for early detection.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Pollock RA, Purvis JM, Apple DF, Jr, Murray HH. Esophageal and hypopharyngeal injuries in patients with cervical spine trauma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1981;90:323–327. doi: 10.1177/000348948109000406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witwer BP, Resnick DK. Delayed esophageal injury without instrumentation failure: complication of anterior cervical instrumentation. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16:519–523. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200312000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanci M, Toprak M, Sarioglu AC, Kaynar MY, Uzan M, Islak C. Oesophageal perforation subsequent to anterior cervical spine screw/plate fixation. Paraplegia. 1995;33:606–609. doi: 10.1038/sc.1995.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferreira LE, Simmons DT, Baron TH. Zenker’s diverticula: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and flexible endoscopic management. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salam MA, Cable HR. Acquired pharyngeal diverticulum following anterior cervical fusion operation. Br J Clin Pract. 1994;48:109–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ba AM, LoTempio MM, Wang MB. Pharyngeal diverticulum as a sequela of anterior cervical fusion. Am J Otolaryngol. 2006;27:295–297. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Summers LE, Gump WC, Tayag EC, Richardson DE. Zenker diverticulum: a rare complication after anterior cervical fusion. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:172–175. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31802c1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sood S, Henein RR, Girgis B. Pharyngeal pouch following anterior cervical fusion. J Laryngol Otol. 1998;112:1085–1086. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100142525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joanes V, Belinchon J. Pharyngoesophageal diverticulum following cervical corpectomy and plating. Case report. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9:258–260. doi: 10.3171/SPI/2008/9/9/258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goffart Y, Moreau P, Lenelle J, Boverie J. Traction diverticulum of the hypopharynx following anterior cervical spine surgery. Case report and review. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100:852–855. doi: 10.1177/000348949110001012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pichler W, Maier A, Rappl T, Clement HG, Grechenig W. Delayed hypopharyngeal and esophageal perforation after anterior spinal fusion: primary repair reinforced by pedicled pectoralis major flap. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:E268–E270. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000215012.84443.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roche M, Gilly F, Carret JP, Guibert B, Braillon G, Dejour H. Perforation of the cervical esophagus and hypopharynx complicating surgery by an anterior approach to the cervical spine. Ann Chir. 1989;43:343–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nourbakhsh A, Garges KJ. Esophageal perforation with a locking screw: a case report and review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:E428–E435. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318074d56c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matz PG, Pritchard PR, Hadley MN. Anterior cervical approach for the treatment of cervical myelopathy. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:S64–S70. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000215399.67006.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geyer TE, Foy MA. Oral extrusion of a screw after anterior cervical spine plating. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:1814–1816. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200108150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fountas KN, Kapsalaki EZ, Machinis T, Robinson JS. Extrusion of a screw into the gastrointestinal tract after anterior cervical spine plating. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19:199–203. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000164164.11277.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konstantakos AK, Temes RT. Delayed esophageal perforation: a complication of anterior cervical spine fixation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:349. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01370-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamesch P, Dralle H, Blauth M, Hauss J, Meyer HJ. Perforation of the cervical esophagus after ventral fusion of the cervical spine. Defect coverage by muscle-plasty with the sternocleidomastoid muscle: case report and review of the literature. Chirurg. 1997;68:543–547. doi: 10.1007/s001040050228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Losken A, Rozycki GS, Feliciano DV. The use of the sternocleidomastoid muscle flap in combined injuries to the esophagus and carotid artery or trachea. J Trauma. 2000;49:815–817. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200011000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuji T, Kuratsu S, Shirasaki N, Harada T, Tatsumi Y, Satani M, Kubo M, Hamada H. Esophagocutaneous fistula after anterior cervical spine surgery and successful treatment using a sternocleidomastoid muscle flap. A case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;267:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Navarro R, Javahery R, Eismont F, Arnold DJ, Bhatia NN, Vanni S, Levi AD. The role of the sternocleidomastoid muscle flap for esophageal fistula repair in anterior cervical spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:E617–E622. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000182309.97403.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seidl RO, Niedeggen A, Todt I, Westhofen M, Ernst A. Infrahyoid muscle flap for pharyngeal fistulae after cervical spine surgery: a novel approach—report of six cases. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:501–505. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0202-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reid RR, Dutra J, Conley DB, Ondra SL, Dumanian GA. Improved repair of cervical esophageal fistula complicating anterior spinal fusion: free omental flap compared with pectoralis major flap. Report of four cases. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:66–70. doi: 10.3171/spi.2004.100.1.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones WG, 2nd, Ginsberg RJ. Esophageal perforation: a continuing challenge. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;53:534–543. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(92)90294-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]