Abstract

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (KHE) is a rare locally aggressive vascular tumor that usually presents as a superficial or deep soft tissue mass with associated cutaneous lesions. We report a unique spinal KHE with painless thoracic scoliosis in a 14-year-old girl. She underwent simultaneous tumor biopsy, spinal deformity correction and fusion. At 3 years follow-up, the patient’s MRI showed no significant deterioration of process without any therapy. KHE presenting as scoliosis is rare and to our knowledge this is the first recognized case in the reported world literature.

Keywords: Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, Scoliosis, Treatment

Introduction

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (KHE) is a rare vascular tumor of infants and adolescents. It most often occurs in the trunk, extremities, and retroperitoneum, although the lesions sometimes occur on the head and neck [1]. Eight cases of KHE have been reported in bone, one of which was located in spine [1–8].We report a unique case of spinal KHE with painless thoracic scoliosis without Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon (KMP) or cutaneous lesions. The patient had been misinterpreted as adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. This report points out that a rigid and rapidly progressive curve pattern should alert physicians to conduct further investigation for assumed idiopathic scoliosis.

Case report

A 14-year-old girl had no complaint of back pain or limitation of physical activity except for rapid progression of her scoliosis with brace treatment. She denied any numbness, tingling, or weakness in her lower extremities. She was not easily bruised or subject to bleeding and not admitted for other diseases. On physical examination, the child was afebrile without abnormal vital signs or weight loss. No local tenderness and percussion pain could be felt by the girl. No masses were palpable and there were no overlying skin changes, erythema, and discoloration. No lymph nodes were palpable. Neurologic deficit was not found. Laboratory workup included complete blood count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel (including liver enzymes, calcium, phosphorus, and alkaline phosphatase), C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate. All results were within normal range.

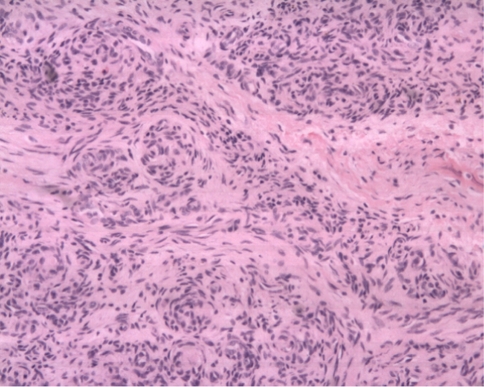

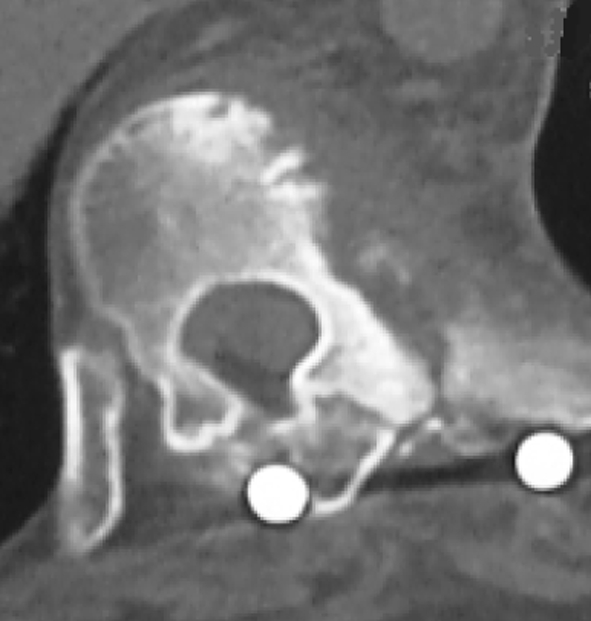

Preoperative radiographic studies included plain radiographs, CT, MRI of the thoracic and lumbar spine. Plain radiographs revealed a right thoracic curve with a Cobb angle of 89° (Fig. 1). On the right side bending film, the curve was reduced to 68°. CT scans showed mixed sclerotic and lytic lesions involving the left side of the vertebral bodies of T8–9 (Fig. 2), and sclerotic lesions in the left pedicles, transverse processes, and rib heads of T8 and T9. MRI revealed hypointense signal abnormality on T2-weighted images in T8–9. There was an associated abnormal soft tissue mass paralleling the left lateral aspect of the vertebral bodies from T5–12 (Fig. 3). There was no cord compression or epidural mass.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative AP standing full spine X-ray shows a right thoracic curve with a Cobb angle of 89°

Fig. 2.

A CT scan in the axial plane of T9 shows mixed lytic and sclerotic bone lesions in the left vertebral body

Fig. 3.

T2-weighted coronal MR image shows signal changes in soft tissue of T5–12

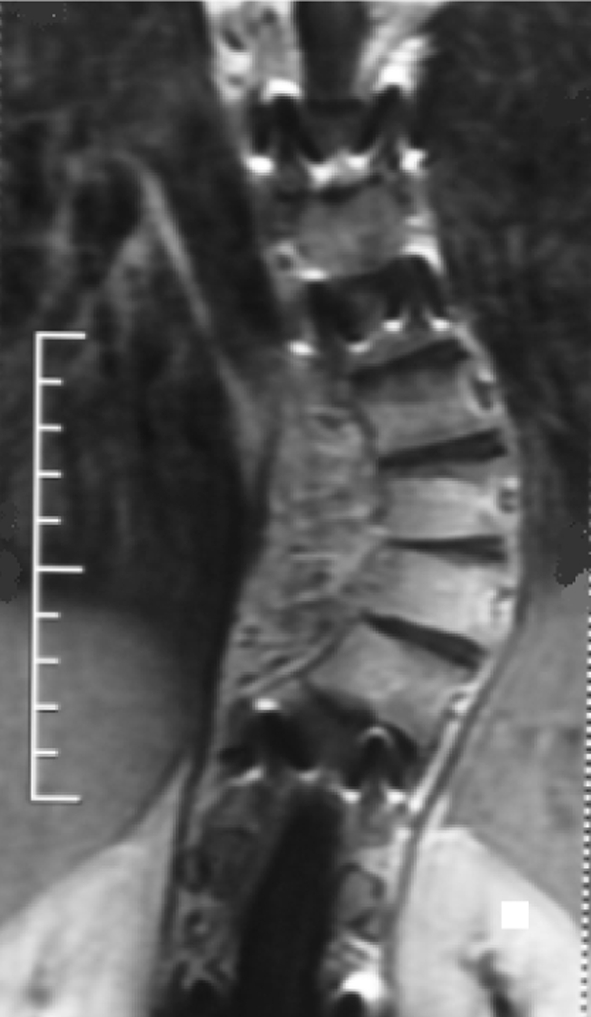

Taking into account the lesion mainly located in the left lateral aspect of the vertebral body, needle biopsy may cause vascular injury, and the positive rate of bone tissue biopsy is not high in our hospital, so we decided to perform open biopsy. Curettage biopsy of the left lateral aspect of the vertebral bodies of T9 was performed through a small incision. Intraoperative frozen section resulted in a pathologic assessment that was inconclusive, but the possibility of tuberculosis was considered. No obvious tumor or inflammation representation was found in the postural spinal structure, so we performed simultaneous posterior deformity correction and fusion with CDH instrumentation from T2 to L3 (Fig. 4).

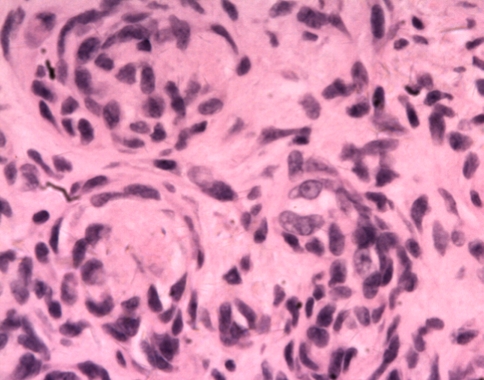

Fig. 4.

Postoperative whole spine film shows a pedicle screw-fixed spine. The thoracic curve measured 22°

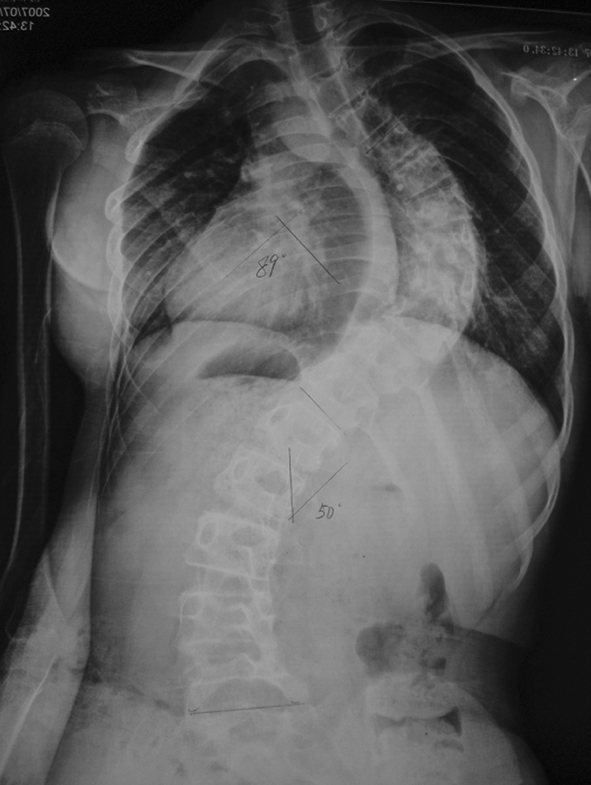

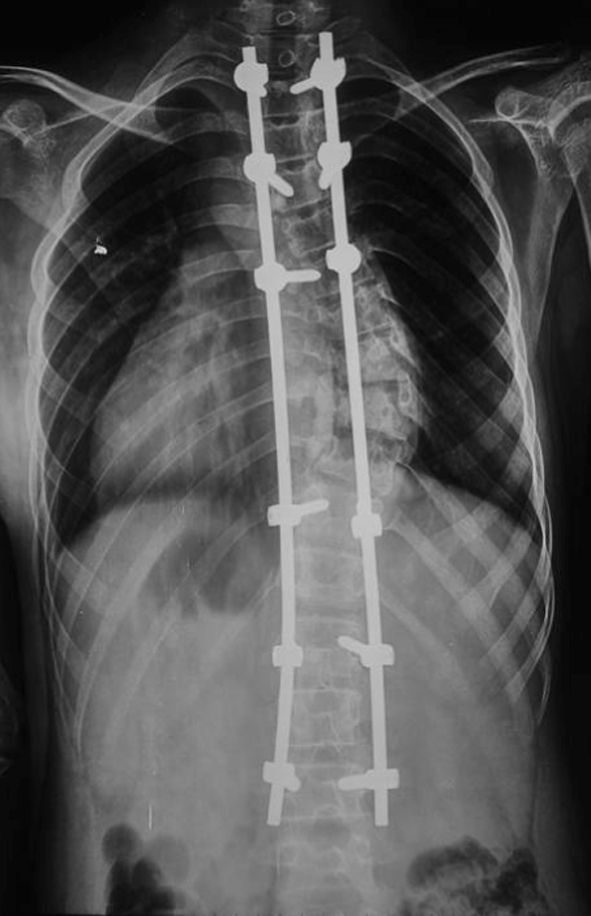

Epithelioid granulomatous lesion was found in the intraoperative frozen section, so the initiatory diagnosis was considered as tuberculosis. Acid-fast bacilli stain was negative. Microscopic examination of the mass confirmed the lesion to be KHE based on morphological findings. Microscopically, the tumor consisted of glomeruloid-like solid nests interspersed with capillaries. The glomeruloid nests were made up of spindle and round cellsc (Fig. 5). The spindled zones merged with glomeruloid nests of rounded to oblong epithelioid cells (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

A photomicrograph shows KHE composed of glomeruloid nests of spindled and epithelioid cells. (Stain, hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, ×100)

Fig. 6.

A high-power view shows glomeruloid areas characterized by small, thin-walled vascular channels merging with rounded, epithelioid cells (Stain, hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, ×400)

We suggested a lateral resection of the tumor, but the patient refused. The patient had no perioperative problems and was discharged in the usual period of time. At 3 years follow-up, the patient had no complaint of back pain or other indisposition. The postoperative 1 year CT and postoperative 3 years MRI showed no significant deterioration of the process without any therapy (Figs. 7, 8).

Fig. 7.

A CT scan in the axial plane of T9 shows no significant deterioration of the soft tissue mass and bone changes 1 year after operation

Fig. 8.

MRI shows no significant growth of tumor 3 years after operation

Discussion

KHE is a rare borderline vascular tumor with locally aggressive behavior that mainly occurs during early childhood. It was first described in 1993 by Zukerberg et al. [9]. It most commonly presents as a superficial or deep soft tissue mass with associated cutaneous lesions, and in most cases is associated with KMP. The tumor tends to be locally invasive, but are not known to produce distant metastases. Clinically, KHE is typically an ill-defined, red to purple indurated plaque frequently complicated by KMP, and looks quite different from infantile hemangioma [1], with little tendency to involute spontaneously [2]. KHE can occur with or without KMP, which is marked by severe thrombocytopenia and a variable degree of anemia. Most of the KHEs present with KMP, namely coagulopathic KHE, and cause significant mortality by a deadly haemorrhage [2, 9]. KHE generally occurs in the soft tissues, and only rarely has been reported to invade bone [1–8].Of the cases of KHE invasion into bone, only one has been reported in spine [8].

Our case presented a difficult diagnostic challenge, given the confusing clinical and imaging findings. The patient did not present with any of the currently described characteristic physical examination findings of KHE, such as palpable mass or blue–red skin lesions, nor did she have abnormal laboratory values suggestive of thrombocytopenia related to KMP. Mixed lytic and sclerotic bony involvement was evident at multiple thoracic spine levels on CT with extensive soft tissue involvement on MRI. The clinical, radiographic, and laboratory findings raised an extensive differential diagnosis that included tuberculosis, nonspecific infection, metastatic neuroblastoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, hemangiomatosis, lymphangiomatosis and lymphoma. Intraoperative frozen section resulted in a pathologic assessment that was inconclusive, but the possibility of tuberculosis was considered. Open biopsy then was performed with sampling of the vertebral body. After review by pathologists with expertise, the diagnosis of KHE was rendered. It is difficult to make a diagnosis of KHE in a patient who does not have cutaneous skin changes, laboratory changes (specifically thrombocytopenia), and bony changes without specificity.

Treatment experience of KHE is limited by its rarity. Lyons et al. [2] insisted that it would not regress in the absence of therapy. And the most effective treatment of KHE is complete surgical excision [5, 9–11]. Tumors limited to the superficial soft tissues are best treated by wide local excision with clear surgical margins [14]. In cases with isolated KHE, excision alone or combined with radiation therapy or other neoadjuvant therapy was the only treatment that eradicated the disease [9]. Masses located in the retroperitoneum are typically extensive, unresectable lesions associated with KMP and frequently lead to patient death [12]. Management of KMP has been proved to be a most problematic issue in KHE, and a multimodality approach using steroids, interferon, and cytotoxic agents may be required [13]. The two most commonly used medical therapies are steroids and interferon [3]. In the eight cases reporting primary bony involvement, six cases involved surgical excision, whereas prednisone and interferon were used in the other two cases. According to the literature, the better results were obtained with excision [1–8]. Because of its rarity, there are no known treatment guidelines for KHE. The decision as to whether or not to treat a noncoagulopathic KHE should be based on the size and location of the tumor and the possible side effects of therapy. Our patient had multilevel spine involvement without associated KMP. The lesion was not resected, and she did not accept other neoadjuvant therapy. At 3 years follow-up, the patient’s MRI showed no significant deterioration of process.

Idiopathic scoliosis is the most common form of spinal deformity. As illustrated in our case, stiffness and a rapid progression of the curve should raise suspicion of an underlying pathological cause [14]. Spinal tumor may cause spinal structure destruction, pain and deformity. Such as osteoid osteoma, have been known to cause scoliosis, but this is probably due to irritative spasm, and the curve and pain usually disappear after tumor removal [15]. In our study, the tumor mass was located in the concave side of the apex of the curve. The proposed mechanism of this patient could be: (1) tumor expansion produced destruction of the lateral vertebral elements, which resulted in scoliosis progression; (2) coexistent KHE and adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Because the patient was asymptomatic, irritable spasm-induced scoliosis was less likely.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gruman A, Liang MG, Mulliken JB, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma without Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:616–622. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyons LL, North PE, Mac-Moune Lai F, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: a study of 33 cases emphasizing its pathologic, immunophenotypic, and biologic uniqueness from juvenile hemangioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:559–568. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200405000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeFatta RJ, Verret DJ, Adelson RT, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: case report and literature review. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1789–1792. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000176539.94515.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai FM, Allen PW, Yuen PM, et al. Locally metastasizing vascular tumor. Spindle cell, epithelioid, or unclassified hemangioendothelioma? Am J Clin Pathol. 1991;96:660–663. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/96.5.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lalaji TA, Haller JO, Burgess RJ. A case of head and neck kaposiform hemangioendothelioma simulating a malignancy on imaging. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:876–878. doi: 10.1007/s002470100009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mac-Moune Lai F, To KF, Choi PC, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: five patients with cutaneous lesion and long follow-up. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:1087–1092. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou G, Yang S, Nie X, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: case report and literature review. Chin J Clin Oncol. 2007;4:288–292. doi: 10.1007/s11805-007-0289-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lisle JW, Bradeen HA, Kalof AN. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma in multiple spinal levels without skin changes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2464–2471. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0838-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zukerberg LR, Nickoloff BJ, Weiss SW. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma of infancy and childhood: an aggressive neoplasm associated with Kasabach–Merritt syndrome and lymphangiomatosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:321–328. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199304000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birchler MT, Schmid S, Holzmann D, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma arising in the ethmoid sinus of an 8-year-old girl with severe epistaxis. Head Neck. 2006;28:761–764. doi: 10.1002/hed.20414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper JG, Edwards SL, Holmes JD. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: case report and review of the literature. Br J Plast Surg. 2002;55:163–165. doi: 10.1054/bjps.2001.3769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss SW, GoldbIum JR (eds) (2001) Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors, 4th edn. Mosby-Harcourt Brace, Philadelphia, pp 891–915

- 13.Hu B, Lachman R, Phillips J, et al. Kasabach–Merritt syndrome-associated kaposiform hemangioendothelioma successfully treated with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and actinomycin D. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1998;20:567–569. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199811000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg CJ, Moore DP, Fogarty EE, et al. Left thoracic curve patterns and their association with disease. Spine. 1999;24:1228–1233. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199906150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aydinli U, Ozturk C, Ersozlu S, et al. Results of surgical treatment of osteoid osteoma of the spine. Acta Orthop Belg. 2003;69:350–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]