Abstract

In a previous report, we demonstrated the efficacy of a cognitively based counseling intervention compared to standard counseling at reducing episodes of unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) among men who have sex with men (MSM) seeking HIV testing. Given the limited number of efficacious prevention interventions for MSM of color (MOC) available, we analyzed the data stratified into MOC and whites. The sample included 196 white MSM and 109 MOC (23 African Americans, 36 Latinos, 22 Asians, eight Alaskan Natives/Native Americans/Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and 20 of mixed or other unspecified race). Among MOC in the intervention group, the mean number of episodes of UAI declined from 5.1 to 1.6 at six months and was stable at 12 months (1.8). Among the MOC receiving standard counseling, the mean number of UAI episodes was 4.2 at baseline, 3.9 at six months and 2.1 at 12 months. There was a significant treatment effect overall (relative risk 0.59, 95% confidence interval 0.35–0.998). These results suggest that the intervention is effective in MOC.

Keywords: HIV, Intervention, Minority men who have sex with men, Cognitive counseling

Introduction

Personalized Cognitive Counseling (PCC) is a single-session cognitively based HIV risk reduction counseling intervention previously shown to be effective in reducing high transmission risk sex in two randomized controlled trials with high-risk HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM) who had repeatedly tested for HIV [1, 2]. The majority of participants in both studies were white, though in the more recent cohort, 36% were MSM of color (MOC).

Recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released data underscoring the disproportionate rates of HIV infection among African Americans and Latinos in the United States. These data showed that the numbers of new infections in the United States were higher than previously thought, that gay and bisexual men of all races continue to account for the greatest number of these new infections, and that people of color were most heavily affected by HIV [3]. That HIV and AIDS incidence rates are high among people of color, especially among African Americans and Latinos, is not new: in fact, it is well known that HIV prevalence rates are three to six times higher in these groups than among white MSM, and in one probability-based CDC survey of MSM an HIV prevalence of 46% among African Americans compared to 21% among whites was recorded [4–6].

These figures suggest that current interventions may not be reaching or impacting MOC to the same extent as white MSM. Such disparities may reflect differences in factors that are associated both with HIV risk behavior and race/ethnicity such as stigma, discrimination, violence, and lack of social support [7–12]. In addition, the effectiveness of counseling interventions might differ between whites and MOC given the evidence that mental health treatment outcomes are often disparate among ethnic/racial minorities [13]. Because of these factors, as well as the limited number of efficacious interventions for MOC that exist [14], we conducted a secondary analysis to measure the efficacy of PCC separately for MOC and for white men who participated in our 2007 study.

Methods

The details of the overall study design, study subject selection, randomization process and interventions have been previously described [1, 2]. Briefly, the study participants were 336 HIV-negative MSM who reported a history of unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) within the previous 12 months with another man whose serostatus was unknown to the participant or was known to be HIV-positive. Participants were recruited when they phoned to set up an appointment for HIV testing at San Francisco’s largest counseling and testing site. Once enrolled, participants were randomized to receive the experimental intervention (PCC) or usual care (UC) counseling provided by trained paraprofessionals.

The UC group received standard CDC client-centered counseling which involves active listening, respect for the client’s concerns, and a general assessment of the participant’s sexual activities and willingness to change based on the stages of change theory to help identify the behaviors and circumstances that place them at risk for HIV [15]. The counselor assesses the client’s knowledge of HIV as well as their sexual and substance use risk behaviors followed by helping the client develop a realistic and incremental plan for reducing their risk for acquiring HIV infection. On average, the UC counseling session lasted 30 minutes.

Men assigned to PCC received standard counseling plus the experimental counseling; the entire session lasted for approximately 50 minutes. In the PCC session, the client was asked to recall a recent memorable episode of insertive or receptive UAI with a non-seroconcordant partner who was not his “boyfriend, partner or lover of at least three months duration.” With that episode in mind, the participant was asked to complete a “self-justifications” questionnaire which contained statements that other MSM had previously identified as having been in their minds when deciding to engage in UAI. Self-justifications are thoughts, attitudes, and beliefs that men employ at the time they chose to engage in high-risk sex and serve as a mechanism that permits the men to participate in an activity that they would otherwise forgo. Common self-justifications include: “I want to have unprotected sex because it feels good” or “he was so healthy looking he could not possibly have HIV.” With the high-risk episode in mind, the participant was asked to complete the self-justification questionnaire by rating, on a scale of 1–4, the strength of each justification at the time he chose to have UAI. Once the self-justification questionnaire was completed, the counselor asked the participant to narrate the episode and the events that led up to it using as much detail as possible and focusing on the participant’s thoughts and feelings about the episode before, during, and after. The counselor then helped the participant identify the self-justifications he used during the episode and asked him to re-evaluate these ideas and the ways in which they may have contributed to the high-risk episode. With these thoughts in mind, the counselor helped the participant to develop a plan to address these in the future.

Risk behaviors were recorded using an audio computer-assisted self-interview immediately preceding the pretest counseling session and again six and 12 months after baseline. A self-administered client satisfaction survey was used to assess the client’s satisfaction with the counseling session and his attitude about the utility of the session.

For this analysis, we assessed the effect of the intervention on numbers of UAI using generalized estimating equations (GEE) negative binomial models to account for repeated measures. Because randomization achieved comparable outcome levels in the two groups at the initial visit, the final models increase efficiency by omitting the parameter for a between-group difference at baseline. The efficacy of treatment was determined separately among all MOC, African American men, Latinos, and whites.

Results

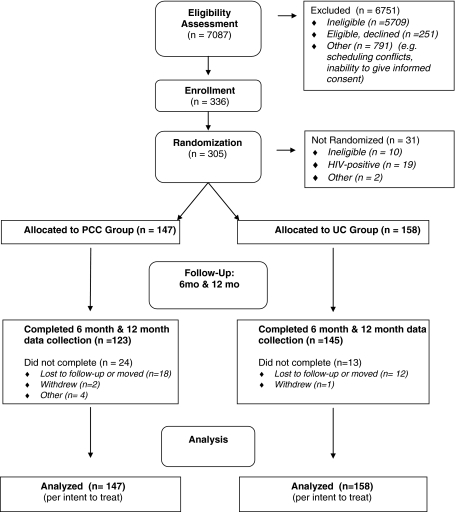

Of the 305 men eligible to participate, 109 (36%) were MOC and 196 (64%) were white. Of the MOC, 23 (21%) were African American, 36 (33%) were Latino, 22 (20%) Asians, 8 (7%) Alaskan Natives/Native Americans/Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and 20 (18%) were mixed or other unspecified race. MOC differed from white participants in age, education, and income, but were similar in terms of recent and long-term STD history as well as numbers of male anal sex partners in the last 90 days (Table 1). Among MOC, 93 (85%) and 97 (89%) attended the six and 12 month visits, respectively, as compared to 186 (95%) and 182 (93%) of the white participants. The study design and flow of participants through the trial is presented in Fig. 1 [2].

Table 1.

Comparison of the characteristics of white MSM and MSM of color study participants at baseline

| Characteristic | MSM of color N (%) | White MSM N (%) | Chi square (χ2) test statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 109 (35.7) | 196 (64.3) | – |

| Age (years) | |||

| 19–30 | 44 (40.4) | 46 (23.5) | 11.94* |

| 31–40 | 47 (43.1) | 92 (46.9) | – |

| 41–60 | 17 (15.6) | 56 (28.6) | – |

| 60+ | 1 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) | – |

| Education | |||

| No degree | 3 (2.8) | 4 (2.1) | 12.51* |

| High school or equivalent | 35 (32.1) | 31 (15.9) | – |

| Associate or bachelor’s degree | 55 (50.5) | 112 (57.4) | – |

| Master’s or doctoral degree | 16 (14.7) | 48 (24.6) | – |

| Annual household income (US$) | |||

| <15,000 | 24 (22.0) | 25 (13.0) | 14.96* |

| 15,000–44,999 | 45 (41.3) | 55 (28.5) | – |

| 45,000–74,999 | 26 (23.9) | 60 (31.1) | – |

| >75,000 | 14 (12.8) | 53 (27.5) | – |

| Not reported** | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.5) | – |

| History of sexually transmitted diseases | |||

| Ever | 67 (61.5) | 139 (70.9) | 2.85 |

| In past year | 21 (19.3) | 48 (24.5) | 1.09 |

| Number of male anal partners in last 90 days | |||

| 0 | 7 (6.4) | 14 (7.1) | 1.52 |

| 1–5 | 85 (78.0) | 141 (71.9) | – |

| 6–24 | 15 (13.8) | 35 (17.9) | – |

| 25+ | 2 (1.8) | 6 (3.1) | – |

* P < 0.05

** Not included in χ2 computation

Fig. 1.

Trial participant recruitment, randomization, and retention

Among MOC, PCC and UC participants reported comparable levels of high-risk sex at baseline (Table 2, P = 0.62). At the six month follow-up, the mean number of episodes of high-risk sex among MOC in the PCC group dropped from 5.1 to 1.6 while there was little change in the UC group (4.2 at baseline and 3.9 at six months). At the 12 month follow-up, the mean number of UAI episodes was stable among the MOC PCC participants (1.8) and declined significantly among the MOC in the UC arm (2.1). The treatment effect among MOC was significant overall (P = 0.049) and at six months (P = 0.02), but not at 12 months (P = 0.60), with borderline evidence that the effect was weaker at 12 than at six months (P = 0.13). We repeated this analysis among African American and Latino men separately and found essentially the same pattern (data not shown).

Table 2.

Mean number of episodes unprotected anal intercourse with a non-primary partner of HIV discordant or unknown serostatus in the preceding 90 days, intervention versus control

| Baseline | 6 Months | 12 Months | Overall | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean number episodes UAIa (standard deviation) | RRb (95% CI) | Mean number episodes UAI (standard deviation) | RR (95% CI) | Mean number episodes UAI (standard deviation) | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | ||||

| PCCc | UCd | PCC | UC | PCC | UC | |||||

| Men of color | 5.1 (11.8) | 4.2 (7.2) | 1.22 (0.56–2.67) | 1.6 (2.1) | 3.9 (8.9) | 0.41 (0.20–0.87) | 1.8 (2.4) | 2.1 (3.8) | 0.84 (0.44–1.60) | 0.59 (0.35–1.00) |

| Whites | 3.8 (7.4) | 5.2 (8.0) | 0.73 (0.45–1.20) | 2.1 (3.9) | 4.6 (9.8) | 0.53 (0.29–0.98) | 1.9 (3.4) | 2.2 (6.0) | 1.04 (0.50–2.18) | 0.74 (0.41–1.33) |

aUnprotected anal intercourse, b relative risk, c personalized cognitive counseling, d usual care

Among whites, risk at baseline was similar among men in the PCC and UC arms (P = 0.22). At six months, the mean number of UAI episodes decreased to 2.1 among men receiving PCC and to 4.6 among men in the UC group. At 12 months, the mean number of episodes of UAI decreased to 1.9 among PCC participants and to 2.2 among UC. Although the treatment effect was significant at six months (P = 0.045), overall the treatment effect was not significant (P = 0.32).

These findings were similar to those reported in the original study for the entire sample, at baseline the mean number of episodes of UAI in the PCC group was 4.2 and in the UC group was 4.8 (P = 0.56). At six months UAI decreased to a mean of 1.9 episodes of UAI in the PCC arm while there was little change in the UC group (P = 0.003). At 12 months the risk reduction in the PCC group persisted (mean of 1.9 episodes of UAI) while the UC group had a significant decline in risk (mean of 2.2 episodes of UAI), resulting in similar levels across groups (P = 0.81).

Compared to whites in the study, MOC reported similar satisfaction with the quality of service they received. Among all MOC receiving PCC, 64% reported that the quality of service they received was “excellent” compared to 71% of white PCC participants (P = 0.47). The proportion of MOC who received PCC compared to white PCC participants who rated their counselor’s competence as “high” was 58% versus 59%, respectively, (P = 0.92). Eighty-two percent of the MOC who received PCC and 77% of the white participants rated their overall satisfaction as “very satisfied” (P = 0.60). In addition, among MOC only, PCC participants compared to UC participants reported similar satisfaction with the quality of services received: 64% of PCC participants ranked the quality of service received as “excellent” compared to 52% of UC participants (P = 0.328). The proportion of MOC who received PCC compared to UC participants who rated their counselor’s competence as “high” was 58% versus 41%, respectively, (P = 0.141). Eighty-two percent of the MOC PCC participants and 71% of UC participants rated their overall satisfaction as “very satisfied” (P = 0.445). Among whites only, PCC participants compared to UC participants expressed significantly higher satisfaction with the following indicators: 71% of white PCC participants reported “excellent” quality of service compared to 55% of white UC participants (P = 0.047); 59% of PCC participants compared to 39% of UC participants rated their counselor’s competence as “high” (P = 0.012), and 77% of PCC participants and 53% of UC participants rated their overall satisfaction as “very satisfied” (P = 0.001).

Discussion

We recognize that this secondary analysis has considerable limitations, including a small sample size, the fact that the study was not designed to specifically test the efficacy of PCC among MOC, and that the study population may not be representative of men testing in other venues. Nevertheless, our experience conducting the intervention with the MOC in our sample supports the conclusion that PCC appears to be effective for all groups at six months and to a lesser degree, for MOC at 12 months.

Among MOC and among whites, the decline in episodes of UAI among PCC participants occurred at six months relative to UC. This pattern was observed in the original analysis as well and was unexpected. It is possible that this is simply an artifact; examination of the number of episodes of UAI at each time point among MOC, whites, and the total population shows similar patterns and by 12 months, the number of episodes of UAI is essentially the same (approximately two episodes of UAI in the previous six months). It is possible that this represents the lowest risk level that can be achieved with a single counseling session in this group of high-risk men. The addition of a second ‘booster’ session six months after the initial counseling may be necessary in order to achieve a greater and more durable decline in risk.

Our findings are encouraging and support those of other studies of counseling interventions that demonstrated success in reducing sexually transmitted diseases, including subgroup analysis by race [16]. Within the context of identifying practical and effective interventions for MOC it is worth noting that all of the intervention counselors in this study were white and most were female, suggesting that programs do not need to limit counseling staff to the race/ethnicity of the target population. Given the importance of finding prevention interventions that are effective in MSM of all races and ethnicities and the differences in our findings among whites and MOC, additional efficacy trials of PCC and other prevention interventions with samples large enough to measure differences across race and ethnic groups are warranted.

Acknowledgment

Financial support for this study was provided by the US National Institutes of Health (grant R01 MH65138).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Dilley JW, Woods WJ, Sabatino J, et al. Changing sexual behavior among gay male repeat testers for HIV: a randomized, controlled trial of a single-session intervention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30(2):177–186. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200206010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dilley JW, Woods WJ, Loeb L, et al. Brief cognitive counseling with HIV testing to reduce sexual risk among men who have sex with men: results from a randomized controlled trial using paraprofessional counselors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:569–577. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318033ffbd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Subpopulation estimates from the HIV incidence surveillance system–United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mort Wkly Rep. 2008;57(36):985–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harawa NT, Greenland S, Bingham TA, et al. Associations of race/ethnicity with HIV prevalence and HIV-related behaviors among young men who have sex with men in seven urban centers in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35(5):526–536. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200404150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blair JM, Fleming PL, Karon JM. Trends in AIDS incidence and survival among racial/ethnic minority men who have sex with men, the United States, 1990–1999. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31(3):339–347. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200211010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valleroy LA, MacKellar DA, Karon JM, et al. HIV prevalence and associated risks in young men who have sex with men. JAMA. 2000;284(2):198–204. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostrow DG, Whitaker RE, Frasier K, et al. Racial differences in social support and mental health in men with HIV infection: a pilot study. AIDS Care. 1991;3:55–63. doi: 10.1080/09540129108253047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant LM, Ostrow DG. Perceptions of social support and psychological adaptation to sexually acquired HIV among white and African American men. Soc Work. 1995;40:215–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stokes JP, Vanable PA, McKirnan D. Ethnic differences in sexual behavior, condom use, and psychosocial variables among black and white men who have sex with men. J Sex Res. 1996;33:373–381. doi: 10.1080/00224499609551855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siegel K, Epstein JA. Ethnic-racial differences in psychological stress related to gay lifestyle among HIV-positive men. Psychol Rep. 1996;79:303–312. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1996.79.1.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldman MB, Ream GL, Diaz RM, El-Bassel N. Intimate partner violence and HIV sexual risk behavior among Latino gay and bisexual men: the role of situational factors. J LGBT Health Res. 2007;3(4):75–87. doi: 10.1080/15574090802226618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warren JC, Fernandez I, Harper GW, Hidalgo MA, Jamil OB, Torres RS. Predictors of unprotected sex among young sexually active African American, Hispanic, and White MSM: the importance of ethnicity and culture. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:459–468. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9291-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mental health: culture, race, and ethnicity – a supplement to mental health: a report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service; 2001. [PubMed]

- 14.Johnson WD, Diaz RM, Flanders WD, et al. Behavioral intervention to reduce risk for sexual transmission of HIV among men who have sex with men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 16 Jul 2008; (3). doi:10:1002/14561858.CD001230.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.UCSF AIDS Health Project . Building quality HIV prevention counseling skills: The basic I training, a training curriculum for counselors working in the context of HIV counseling and testing. 4. San Francisco, CA: University of California at San Francisco; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bolu OO, Lindsey C, Kamb ML, et al. Is HIV/sexually transmitted disease prevention counseling effective among vulnerable populations?: a subset analysis of data collected for a randomized, controlled trial evaluating counseling efficacy (Project Respect) Sex Transm Dis. 2004;21(8):469–474. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000135987.12346.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]