Abstract

The Maternal and Child Health Bureau commissioned the American College of Medical Genetics to outline a process for the standardization of outcomes and guidelines for state newborn screening programs and to define responsibilities for collecting and evaluating outcome data, including a recommended uniform panel of conditions to include in state newborn screening programs. The expert panel identified 29 conditions for which screening should be mandated. An additional 25 conditions were identified because they are part of the differential diagnosis of a condition in the core panel, they are clinically significant and revealed with screening technology but lack an efficacious treatment, or they represent incidental findings for which there is potential clinical significance. The process of identification is described, and recommendations are provided.

Keywords: Newborn screening, genetics, public health, congenital, metabolic disease

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, newborn screening is a highly visible and important state-based public health program that began over 40 years ago. States and territories mandate newborn screening of all infants born within their jurisdiction for certain disorders that may not otherwise be detected before developmental disability or death occurs. Newborns with these disorders typically appear normal at birth. Appropriate compliance with the medical management prescribed can allow most affected newborns to develop normally. As the model for public health-based population genetic screening, newborn screening is nationally recognized as an essential program that aims to ensure the best outcome for the nation’s newborn population.

Aside from the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) “Standard on Blood Collection on Filter Paper” and guidance from the Council of Regional Networks for Genetic Services (CORN), funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), there are no national newborn screening standards, and limited advice is available from national advisory committees and national medical or public health professional organizations regarding newborn screening policies and conditions to be included in screening mandates. The level of state resources available (personnel, equipment, service capacity); the programs’ interpretations of available evidence concerning given conditions (incidence, treatability, impact); the availability or expense of new screening methodologies; or public advocacy by families, health care professionals or state legislators have often led to divergence among states regarding which conditions should be mandated for newborn screening. This divergence has resulted in significant disparities in screening services available to infants. Indeed, in 1999, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Newborn Screening Task Force indicated that greater uniformity among programs would benefit families, professionals, and public health agencies.

The public health system faces many challenges as newborn screening capabilities continue to evolve. The health care service infrastructure is limited with regard to the interconnections among primary care professionals and subspecialists, particularly in rural areas, a problem complicated by the number and diversity of very rare conditions identified in newborn screening programs. There are geographic limitations in the availability of specific expertise for many of the rare conditions, and considerable needs exist in the areas of training and education about the disorders detected through newborn screening programs throughout the health care system. Furthermore, improvements in the newborn screening system and the expansion of the number of conditions for which screening is offered have costs, and these costs and the associated benefits seem to accrue independently of the public and private health care delivery systems, which complicates their integration. Many states provide the programs necessary to ensure that screening and diagnosis will occur, but they are limited in their ability to ensure long-term management, including the provision of the necessary treatment and services.

In addition, new technologies have brought three major challenges to newborn screening: 1) expanding knowledge base of the etiology and therefore the treatment or potential treatment of genetic diseases; 2) rapid expansion of diverse technologies such as multiplex platforms that may be used in screening; 3) increased use of tiered testing strategies to enhance the positive predictive value of an initial abnormal result. The lack of newborn screening program uniformity for infants, the changing dynamics of emerging technology, and the complexity of genetics require an assessment of the state of the art in newborn screening and a perspective on the future directions such programs could take. In 1999, the AAP Newborn Screening Task Force recommended that “HRSA should engage in a national process involving government, professionals, and consumers to advance the recommendations of this Task Force and assist in the development and implementation of nationally recognized newborn screening system standards and policies.”

In response to this need, the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) of HRSA commissioned the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) to outline a process of standardization of outcomes and guidelines for state newborn screening programs and to define responsibilities for collecting and evaluating outcome data, including a recommended uniform panel of conditions to include in state newborn screening programs. It was expected that the analytical endeavor and subsequent recommendations would be definitive and that the subsequent recommendations be based on the best scientific evidence and analysis of that evidence. ACMG was specifically asked to develop recommendations to address:

A uniform condition panel (including implementation methodology);

Model policies and procedures for state newborn screening programs (with consideration of a national model);

Model minimum standards for state newborn screening programs (with consideration of national oversight);

A model decision matrix for consideration of state newborn screening program expansion; and

Consideration of the value of a national process for quality assurance and oversight.

This report is a response to the HRSA/MCHB request.

I. DEVELOPING A UNIFORM SCREENING PANEL

As indicated above, the AAP Task Force was concerned particularly about the lack of uniformity between the state-based newborn screening programs and the need for “nationally recognized newborn screening system standards and policies.” There are few existing systems that allow for the assessment of conditions to determine their appropriateness for newborn screening. In addition to the original Wilson-Jungner criteria, some states (e.g., Nebraska, Washington) have developed such evaluation criteria and systems and other countries (e.g., Australia, Belgium) have developed them as well. However, most use criteria that are either difficult to quantify or that do not allow conditions to be comparatively ranked adequately. Most are inadequate with respect to the handling of conditions that have similar or overlapping disease markers or that may be detected through the use of multiplex technologies but may vary in their analytical and clinical features.

METHODS

ACMG convened a group—the Newborn Screening Expert Group—that included participants with expertise in various areas of subspecialty medicine and primary care, health policy, law, ethics, and public health, as well as consumers, who worked with a steering committee and several expert work groups. As an initial step in the process, the expert group developed a set of guiding principles for its work. The establishment of these principles was followed by the development of criteria by which conditions were to be evaluated, and the identification of the conditions to be evaluated. A steering committee oversaw the work of this group. Two work groups were formed to provide more in-depth analysis in two specific areas: the uniform panel and its criteria, and the diagnosis and follow-up system.

The expert group used a two-tiered approach to assessing and ranking conditions. In the first tier, using the specific evaluation criteria, conditions were analyzed by recognized experts and other interested individuals to develop a quantification of opinion. In the second tier, the quantification data were subjected to an analysis of the evidence base for each specific screening criterion score. Basic principles developed to guide the decision-making process were factored with the results of these two levels of analysis to arrive at a set of core conditions and the identification of additional clinically significant conditions that could be revealed while establishing the diagnosis or made available by the screening laboratory due to the nature of the technology being employed.

Establishing principles

The following basic principles were developed as a framework for defining the criteria by which to evaluate conditions and make recommendations.

Universal newborn screening is an essential public health responsibility that is critical to improve the health outcome of affected children.

Newborn screening policy development should be primarily driven by what is in the best interest of the affected newborn, with secondary consideration given to the interests of unaffected newborns, families, health professionals, and the public.

Newborn screening is more than testing. It is a coordinated and comprehensive system consisting of education, screening, follow-up, diagnosis, treatment and management, and program evaluation.

The medical home and the public and private components of the screening programs should be in close communication to ensure confirmation of test results and the appropriate follow-up and care of identified newborns.

Recommendations about the appropriateness of conditions for newborn screening should be based on the evaluation of scientific evidence and expert opinion.

- To be included as a primary target condition in a newborn screening program, a condition should meet the following minimum criteria:

- It can be identified at a phase (24 to 48 hours after birth) at which it would not ordinarily be clinically detected;

- A test with appropriate sensitivity and specificity is available for it; and

- There are demonstrated benefits of early detection, timely intervention and efficacious treatment of the condition being tested.

The primary targets of newborn screening should be conditions that meet the criteria listed in number 6 above. The newborn screening program also should report any other result of potential clinical significance.

Centralized health information data collection is needed for longitudinal assessment of disease-specific screening programs.

Total quality management should be applied to newborn screening programs.

Newborn screening specimens are valuable health resources. Every program should have policies in place to ensure confidential storage and appropriate use of specimens.

Public awareness, coupled with professional training and family education, is a significant program responsibility that must be part of the complete newborn screening system.

Choosing conditions

The conditions chosen for evaluation were included for one or more of several reasons:

They are included in private, state, or national newborn screening programs;

They are coincidentally revealed by some of the technologies used in newborn screening;

They were identified by members of the expert group as worthy of consideration;

They were identified by disease-specific advocacy organizations; and/or

They were included in the differential diagnosis of a screening result for another condition.

In the course of collecting information, all conditions were subject to reconsideration. Eighty-four conditions were chosen for consideration.

Developing evaluation criteria and their comparative values

The uniform panel working group developed the criteria by which conditions were to be evaluated. These were modified subsequently by the expert group. Criteria were divided into three main categories that covered aspects of the condition:

The clinical characteristics (e.g., incidence, burden of disease if not treated, phenotype in the newborn);

The analytical characteristics of the screening test (e.g., availability, features of the platform); and

The diagnosis, treatment and management of the condition in both acute and chronic forms (this criterion includes the availability of health professionals experienced in diagnosis, treatment, and management).

Within each of these categories, several component criteria were developed (resulting in a total of 19 criteria) for assigning the comparative value or score. The scoring system recognizes the strengths and limitations of each condition and summarizes them in a ranking system. Thus, a low score in a particular area does not necessarily mean that screening for that condition will never be conducted. In fact, low scores could be radically overruled by scientific evidence of new advances in testing and treatment, and they should be recognized as opportunities for targeted research endeavors and subsequent reconsideration of the condition for inclusion.

The criteria that were developed to differentiate the appropriateness of conditions for newborn screening include some that have a highly objective scientific basis and others that are associated with more subjective aspects. To the extent possible, the expert group relied on the scientific literature to provide the information on which its recommendations are based. However, some criteria have significant subjective aspects that require the consideration of more than just scientific and expert opinion. For example, issues of cost were considered but were not viewed as central in the analyses of the scientific literature. Cost is an example of a subjective criterion because it is a contextual concern and can be measured only against the value of the outcome.

Collecting data

The first tier of the analysis was accomplished through the development of a data collection instrument containing the evaluation screening criteria. A survey was conducted to allow for the input of a wide range of individuals and organizations with interest in newborn screening. The data collection instrument included a methodology not only to collect information from experts, but also to quantify that expert opinion on features of the conditions under consideration for inclusion in a uniform condition panel.

Before wide distribution, the data collection instrument was pilot tested. Potentially ambiguous language was identified and clarified, and scores were modestly adjusted to reflect the evolving priorities of the expert group. After modification, the data collection instrument was made widely available through passive efforts (e.g., listservs of interest groups such as Genetic Alliance, Association of Public Health Laboratories, Association of State and Territorial Health Officials) and active efforts (e.g., direct approaches to experts in the conditions under evaluation and/or to support groups for particular conditions under evaluation). In this way, it was possible to acknowledge broad views that were of a more subjective nature, such as the simplicity of the treatment (parents and individuals with the disorder in question often differed significantly from experts when scoring on such items as simplicity of treatment). The results led to a preliminary listing of conditions and their placement in one of three categories:

High scoring;

Moderately scoring but part of the differential diagnosis of a high scoring condition; and

Low scoring conditions not appropriate for newborn screening at this time.

The quantification of responses from at least three recognized experts for each condition were compared with those of all respondents for that condition and found to be consistent.

Survey results were analyzed statistically. Respondents were characterized to ensure that they were broadly representative of the population. Recognizing that not all who respond have expertise or experience in all aspects of newborn screening for a specific condition, methods were used that allowed data to be aggregated for each criterion for each condition rather than to use the total score for a condition. A mean score for each criterion for each condition was based only on the responses provided for the criterion. Respondents were allowed to insert a “U” if an answer was unknown. The sum of the means was used for the total score assigned to a condition, because the sum of the means tends to acknowledge dissenting views more clearly than does the sum of the medians.

It is recognized that this relatively open survey process limited the views of experts while considering the views of those less knowledgeable about the individual conditions. However, analyses provided by scientific experts showed that their views were in close agreement with those of the majority of respondents.

Establishing and integrating the evidence base

In the second tier of the assessment, the evidence base for the conditions was established and an algorithm through which conditions were reassessed was developed. Each condition was considered with regard to the available scientific evidence, such as systematic reviews of reference lists (including MedLine, PubMed and others); books; Internet searches; professional guidelines; clinical evidence; and cost/economic evidence and modeling surrounding each of the criterion. Their categorization was adjusted in accordance with the evidence. The analysis of the evidence base from the scientific literature included details about the screening tests, the efficaciousness of treatments, and the adequacy of the knowledge base of the condition. Disease-specific fact sheets were developed to describe this evidence.

At least two recognized experts examined the evidence on the fact sheet for all criterion scores for the conditions and assigned the level of evidence for each criterion score, making the scoring system part of a fuller evidence base analysis. Thus, the evaluation of the evidence for the scores in the second tier of analysis is part of a broader assessment of the scientific literature related to the conditions, tests, and treatments. In addition to validating the evidence gleaned from the literature and other sources, these experts assigned a level of quality to the studies from which the evidence was drawn. Adjustments based on the evidence were made primarily on the basis of the accuracy of the information. When significant differences were found between the data collected through the survey and the evidence base, these differences are acknowledged and addressed in each of the fact sheets. Only rarely were adjustments required to align the literature evidence with the views of the scores of survey respondents.

RESULTS

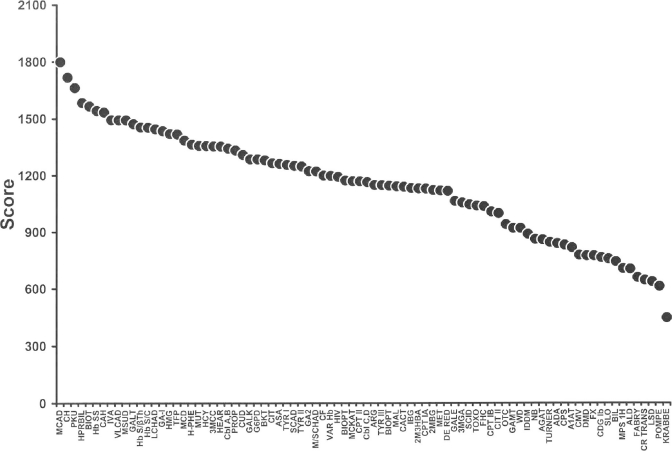

In the first tier of assessment, nearly 300 individuals from the United States and other countries completed the data collection instrument. Many respondents provided information on multiple conditions, thereby yielding information on nearly 4,000 individual disease-specific responses. The complete data are displayed in Table 1 (Scores of All Conditions) and graphically in Figure 1 (Scoring by Test Availability), where the sums of the means are displayed for all conditions. Medium-chain acyl CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) deficiency, congenital hypothyroidism (CH) and phenylketonuria (PKU) were the highest scoring conditions in this evaluation system, followed by biotinidase deficiency (BIOT), sickle cell anemia (Hb SS) and congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). A number of other conditions that scored in the upper third were also found to have an efficacious treatment and sufficient knowledge of natural history to be considered appropriate for newborn screening. Most conditions in the middle third of scores were also included in the differential diagnosis of at least one of the higher scoring conditions. Almost all conditions in the bottom third of scores either lacked a screening test that had been validated in a general newborn population or were deficient in meeting several of the assigned evaluation criteria. Due to limited involvement of infectious disease experts, the expert group chose to defer decision-making on infectious diseases.

Table 1.

Scores of all conditions (sorted in descending order of the sum of the means scores)

| Condition | Code | Score (sum of the means) | Rank (%ile) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency | MCAD | 1799 | 1.00 |

| Congenital hypothyroidism | CH | 1718 | 0.99 |

| Phenylketonuria | PKU | 1663 | 0.98 |

| Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia (Kernicterus) | HPRBIL | 1584 | 0.96 |

| Biotinidase deficiency | BIOT | 1566 | 0.95 |

| Sickle cell anemia (Hb SS disease) | Hb SS | 1542 | 0.94 |

| Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (21-hydroxylase deficiency) | CAH | 1533 | 0.93 |

| Isovaleric acidemia | IVA | 1493 | 0.89 |

| Very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency | VLCAD | 1493 | 0.89 |

| Maple syrup (urine) disease | MSUD | 1493 | 0.89 |

| Classical galactosemia | GALT | 1473 | 0.88 |

| Hb S/β-thalassemia | Hb S/βTh | 1455 | 0.87 |

| Hb S/C disease | Hb S/C | 1453 | 0.86 |

| Long-chain L-3-OH acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency | LCHAD | 1445 | 0.84 |

| Glutaric acidemia type I | GA I | 1435 | 0.83 |

| 3-OH 3-CH3 glutaric aciduria | HMG | 1420 | 0.82 |

| Trifunctional protein deficiency | TFP | 1418 | 0.81 |

| Multiple carboxylase deficiency | MCD | 1386 | 0.80 |

| Benign hyperphenylalaninemia | H-PHE | 1365 | 0.78 |

| Methylmalonic acidemia (mutase deficiency) | MUT | 1358 | 0.77 |

| Homocystinuria (due to CBS deficiency) | HCY | 1357 | 0.76 |

| 3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency | 3MCC | 1355 | 0.75 |

| Hearing loss | HEAR | 1354 | 0.73 |

| Methylmalonic acidemia (Cbl A,B) | Cbl A,B | 1343 | 0.72 |

| Propionic acidemia | PROP | 1333 | 0.71 |

| Carnitine uptake defect | CUD | 1309 | 0.69 |

| Galactokinase deficiency | GALK | 1286 | 0.69 |

| Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency | G6PD | 1286 | 0.67 |

| β-Ketothiolase deficiency | BKT | 1282 | 0.66 |

| Citrullinemia | CIT | 1266 | 0.65 |

| Argininosuccinic acidemia | ASA | 1263 | 0.64 |

| Tyrosinemia type I | TYR I | 1257 | 0.63 |

| Short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency | SCAD | 1252 | 0.61 |

| Tyrosinemia type II | TYR II | 1249 | 0.60 |

| Glutaric acidemia type II | GA2 | 1224 | 0.59 |

| Medium/short-chain L-3-OH acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency | M/SCHAD | 1223 | 0.58 |

| Cystic fibrosis | CF | 1200 | 0.57 |

| Variant hemoglobinopathies (including Hb E) | Var Hb | 1199 | 0.55 |

| Human HIV infection | HIV | 1193 | 0.54 |

| Defects of biopterin cofactor biosynthesis | BIOPT (BS) | 1174 | 0.53 |

| Medium-chain ketoacyl-CoA thiolase deficiency | MCKAT | 1170 | 0.52 |

| Carnitine palmitoyltransferase II deficiency | CPT II | 1169 | 0.51 |

| Methylmalonic acidemia (Cbl C,D) | Cbl C,D | 1166 | 0.49 |

| Argininemia | ARG | 1151 | 0.48 |

| Tyrosinemia type III | TYR III | 1149 | 0.47 |

| Defects of biopterin cofactor regeneration | BIOPT (Reg) | 1146 | 0.46 |

| Malonic acidemia | MAL | 1143 | 0.45 |

| Carnitine: acylcarnitine translocase deficiency | CACT | 1141 | 0.43 |

| Isobutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency | IBG | 1134 | 0.42 |

| 2-Methyl 3-hydroxy butyric aciduria | 2M3HBA | 1132 | 0.41 |

| Carnitine palmitoyltransferase I deficiency (liver) | CPT IA | 1131 | 0.40 |

| 2-Methylbutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency | 2MBG | 1124 | 0.39 |

| Hypermethioninemia | MET | 1121 | 0.37 |

| Dienoyl-CoA reductase deficiency | DE RED | 1119 | 0.36 |

| Galactose epimerase deficiency | GALE | 1066 | 0.35 |

| 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria | 3MGA | 1057 | 0.34 |

| Severe combined immunodeficiency | SCID | 1047 | 0.33 |

| Congenital toxoplasmosis | TOXO | 1041 | 0.31 |

| Familial hypercholesterolemia (heterozygote) | FHC | 1038 | 0.30 |

| Carnitine palmitoyltransferase I deficiency (muscle) | CPT IB | 1009 | 0.29 |

| Citrullinemia type II | CIT II | 1001 | 0.28 |

| Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency | OTC | 942 | 0.27 |

| Guanidinoacetate methyltransferase deficiency | GAMT | 922 | 0.24 |

| Wilson disease | WD | 922 | 0.24 |

| Diabetes mellitus, insulin dependent | IDDM | 891 | 0.23 |

| Neuroblastoma | NB | 864 | 0.22 |

| Arginine: glycine amidinotransferase deficiency | AGAT | 861 | 0.20 |

| Turner syndrome | TURNER | 847 | 0.19 |

| Adenosine deaminase deficiency | ADA | 841 | 0.18 |

| Carbamylphosphate synthetase deficiency | CPS | 833 | 0.17 |

| Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency | A1AT | 819 | 0.16 |

| Congenital cytomegalovirus infection | CMV | 779 | 0.14 |

| Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy | DMD | 776 | 0.12 |

| Fragile X syndrome | FX | 776 | 0.12 |

| Congenital disorder of glycosylation type Ib | CDG Ib | 766 | 0.11 |

| Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome | SLO | 759 | 0.10 |

| Biliary atresia | BIL | 744 | 0.08 |

| Hurler-Scheie disease | MPS-1H | 707 | 0.07 |

| X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy | ALD | 705 | 0.06 |

| Fabry disease | FABRY | 661 | 0.05 |

| Creatine transport defect | CR TRANS | 646 | 0.04 |

| Lysosomal storage diseases | LSD | 638 | 0.02 |

| Pompe disease | POMPE | 613 | 0.01 |

| Krabbe disease | KRABBE | 447 | 0.00 |

Fig. 1.

Scoring by test availability (separates out those conditions that have an acceptable, validated, population-based screening test from those that do not).

A score of 1200 on the data collection instrument was found to provide a logical point of separation between a group of high scoring conditions (1,200–1,799 of a possible 2,100) and another group of low scoring (<1,000) conditions. A group of conditions with intermediate scores (1,000–1,199) was identified, all of which were part of the differential diagnosis of a high scoring core condition, but without an efficacious treatment or without a well understood natural history. With the use of expert opinion and the validated evidence base, each condition that had been previously assigned to a category based on quantified scores was reconsidered based on:

The scientific evidence as to the availability of a screening test;

An efficacious treatment;

An adequate understanding of the natural history;

Whether the condition was part of the differential diagnosis of another condition; and

Whether the screening test results related to a clinically significant condition.

The categories were referred to as: 1) the core panel; 2) secondary targets (conditions that are part of the differential diagnosis of a core panel condition); and 3) not appropriate for newborn screening (either no newborn screening test is available or there is poor performance with regard to multiple other evaluation criteria).

DISCUSSION

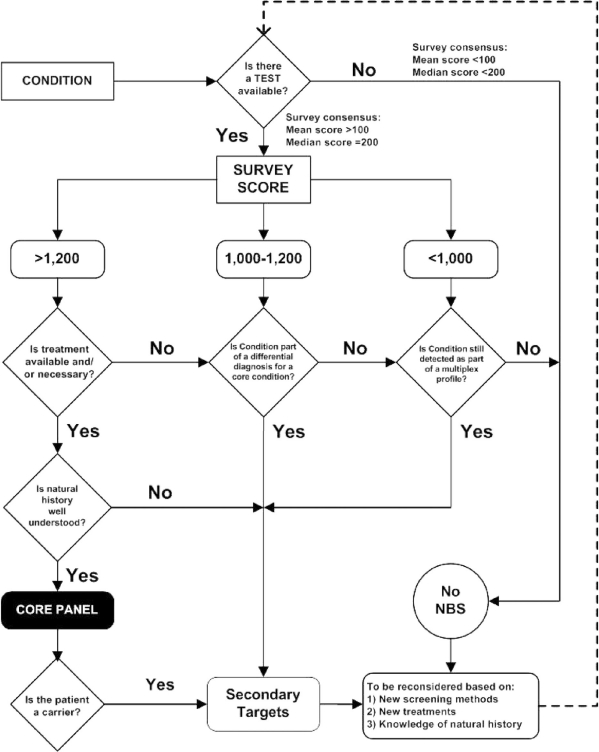

The basis for decision-making started with whether a screening test is available, which was then overlaid by the overall quantified expert opinion analysis gathered via the data collection information tool. The process of quantifying this expert opinion was then informed by literature review and expert validation.

In the first tier of analysis, conditions with scores above 1,200 met key criteria and were preliminarily considered appropriate for inclusion in a core newborn screening panel. Conditions scoring below 1,000 were not considered appropriate for inclusion in the core newborn screening panel at this time. As noted previously, the expert group determined that the laboratory should report any result coincidentally revealed in the course of newborn screening that might be clinically significant. In general, the screening test has been optimized for the detection of primary target conditions. Optimizing the technology for a primary target condition does not necessarily optimize the detection of all possible conditions. These conditions are often revealed through diagnostic testing since they are part of the differential diagnosis of a core condition as occurs with MS/MS identified cases but may be apparent in the screening laboratory due to the technologies employed in screening (e.g., hemoglobinopathies by high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC)/isoelectric focusing (IEF)). Hence, the expert group designated a category of “secondary targets” to include conditions for which the results should be made available to health care professionals and/or families by the screening laboratory or that are determined during the diagnostic phase of the screening program and provided to families in the course of diagnosis and follow-up. Most conditions placed in the secondary target category are part of the differential diagnosis of a condition in the core panel. Inclusion in the secondary target category allows for the collection of cases on a national level for further investigation to understand the disease process, and for the development of treatment modalities. Regardless of whether programs choose to integrate all such conditions into their broader newborn screening programs, it will be important for them to have the diagnostic confirmatory results for all such cases, since they have a direct impact on the calculation of false-positive rates of screening for the core panel conditions.

After conditions were preliminarily categorized based on their data collection instrument scores, the evidence base, as reflected in fact sheets developed for each condition, was assessed. If a clinically significant condition in the core panel did not have the scientific evidence to support the availability of an efficacious treatment, it moved to the secondary target category. Similarly, if it was determined that an understanding of the natural history of the condition was insufficient to justify primary screening, the condition was moved to the secondary target category. When test results definitively identified carriers of the conditions, the handling of carrier information was moved into the secondary target category.

The following flow diagram (Fig. 2) demonstrates the decision-making algorithm. It is important to note that the algorithm presumes an ongoing review of conditions to determine their continued or newly identified appropriateness for newborn screening as new tests and treatment evolve. The data collection instrument used in this project provides an assessment of only one aspect of a broader decision-making process required for establishing a newborn screening uniform panel. An ongoing analysis of the scientific evidence must be overlaid on the quantified expert opinion.

Fig. 2.

Condition evaluation and decision-making algorithm.

Clearly, the first decision to screen is based on the availability of a sensitive and specific screening test that can be done in the 24- to 48-hour interval after birth. There are a total of 29 conditions considered appropriate for newborn screening because they have a screening test, an efficacious treatment, and there is adequate knowledge of natural history (see Table 2). The conditions best meeting all of the criteria established by the expert group are MCAD, CH and PKU. Among conditions assigned to the core panel are nine organic acidurias; six amino acidurias; five disorders of fatty oxidation; three hemoglobinopathies associated with an Hb S allele; and six other conditions. Twenty-three of the 29 conditions in the core panel are identified with multiplex technologies such as MS/MS.

Table 2.

Newborn screening panel: core panel and secondary targets

| MS/MS

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acylcarnitines

|

Amino acids

|

|||

| 9 OA | 5 FAO | 6 AA | 3 Hb Pathies | 6 Others |

| CORE PANEL | ||||

| IVA | MCAD | PKU | Hb SS* | CH |

| GA I | VLCAD | MSUD | Hb S/βTh* | BIOT |

| HMG | LCHAD | HCY* | Hb S/C* | CAH* |

| MCD | TFP | CIT | GALT | |

| MUT* | CUD | ASA | HEAR | |

| 3MCC* | TYR I* | CF | ||

| Cbl A,B* | ||||

| PROP | ||||

| BKT | ||||

| SECONDARY TARGETS | ||||

| 6 OA | 8 FAO | 8 AA | 1 Hb Pathies | 2 Others |

| Cbl C,D* | SCAD | HYPER-PHE | Var Hb* | GALK* |

| MAL | GA2 | TYR II | GALE | |

| IBG | M/SCHAD | BIOPT (BS) | ||

| 2M3HBA | MCKAT | ARG | ||

| 2MBG | CPT II | TYR III | ||

| 3MGA | CACT | BIOPT (REG) | ||

| CPT IA | MET | |||

| DE RED | CIT II | |||

NOTE: Codes are as follows: OA, disorders of organic acid metabolism; FAO, disorders of fatty acid metabolism; AA, disorders of amino acid metabolism; Hb Pathies, hemoglobinopathies.

Identifies conditions for which specific discussions of unique issues are found in the main report.

On the basis of the evidence, 6 of the 35 conditions placed initially in the core panel were moved into the secondary target category, which expanded to 25 conditions that are part of the differential diagnosis of a core panel condition. Knowledge of these secondary targets (i.e., in a newborn screening test result or in follow-up) can be clinically important to the family.

In addition to the 54 conditions identified in Table 2, the expert group identified 27 other conditions that were not considered appropriate for newborn screening, either because they met few evaluation criteria or because they lacked a screening test.

Limitations

Conditions with limited evidence reported in the scientific literature were more difficult to evaluate using the data collection instrument. For example, some conditions have been reported in 10 or fewer families in the world. Many conditions were found to occur in multiple forms distinguished by age-of-onset, severity or other features. Further, unless a condition was already included in newborn screening programs, a potential for bias was apparent in the information related to some criteria. The power of the statistical analyses and the blending of two forms of evaluation also presented limitations. The data collection process in the first tier of the analysis was limited also by the significant variability in the numbers of individuals responding for the different conditions. Due to limitations in the scientific evidence of these rare diseases, there was significant reliance on the opinions of experts in the conditions. There were many conditions that scored close to other conditions and it is unlikely that the statistical power provided in these analyses was sufficient to truly discriminate among them in a ranking system. Nevertheless, groups of scores were assessed and natural separations between groups became apparent. In such circumstances, expert opinion with reasoning that applied first principles of genetic medicine to the evidence and to the quality underlying the data determined the placement of the conditions into particular categories.

II. THE NEWBORN SCREENING SYSTEM: PROGRAM EVALUATION COST-EFFECTIVENESS AND FUTURE NEEDS

The newborn screening system

Because the appropriate functioning of the newborn screening system is critical to realizing improved outcomes, the components of a screening program and system were examined by the expert group during the project (information was obtained from program reports submitted to the National Newborn Screening and Genetics Resource Center (NNSGRC) and is based on information available as of October 2003). The goal of the evaluation was to determine the extent to which States have addressed the many aspects of the components of this system and to recommend performance standards to improve the quality of the system. The ability to properly ensure appropriate diagnosis and management is considered to be primarily a systems responsibility. Limitations and significant variability were identified in components of prenatal education, screening, follow-up, diagnosis, management, and program management. For example:

Financing across State and county lines is constrained by State-based Medicaid rules;

Service delivery is fragmented on a categorical or disease basis;

There is insufficient support to bridge geographic barriers;

It is difficult to identify experienced health care professionals for complex care (e.g., centers of excellence for genital reconstructive surgery for CAH; confirmation of metabolic diagnoses);

There is misinterpretation of privacy regulations (e.g., the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act or HIPAA);

There is underutilization and lack of uniformity of information technology;

Collaborative management and care is often constrained by systems of reimbursement for services;

State sovereignty sometimes dictates individual approaches; and

There is variability in financing of screening programs.

There are both national and State roles in addressing these limitations, and states must retain their significant roles and responsibilities. They have clear authority with regard to oversight and evaluation, as well as enforcement. There is a need to integrate the various systems of health care coverage and payment through flexible and comprehensive financing of services. Service coordination at both State and local levels must be considered, as well as program integration with the State Children’s Health Insurance Plan, early intervention programs, Title V programs, and similar services.

It is apparent, however, that all State programs could benefit from a more robust national role in newborn screening. Because so many of the conditions screened in newborns or under consideration for screening are rare, most States that undertake evaluations of the scientific basis for screening of conditions must rely on the same relatively small group of patients identified throughout the world. There is a potential national role in providing scientific evaluation of conditions and defining core condition panels. This would allow States to apply the best science to their own considerations when determining their role in expanded screening.

Practice guidelines also could be developed at a national level by interested organizations. The expert group identified a clear gap in the information available and information needed by primary care professionals to facilitate an immediate response in the event of a screen–positive infant. In response, the expert group has developed an Action (ACT) Sheet for each core condition and secondary target to facilitate immediate response on the part of primary care professionals, both with regard to the need for speed and the expected steps in diagnosis and follow-up.

There are also potentially expanded national roles in oversight, data collection, program evaluation, and the development of educational materials to support newborn screening. Depending on the overall incidence of particular conditions, regional collaborative groups such as those funded by HRSA could:

Coordinate access to health care professionals;

Serve as coordinators and repositories for data collection;

Provide long-term follow-up capability when resources and expertise are limited;

Facilitate transition (and access) from pediatric to adult care; and

Provide education.

The distribution of primary, secondary, and tertiary services is largely based on the incidence of a condition and the complexity of its short- and long-term diagnosis and management. For more common conditions with easier diagnosis and follow-up, there is likely to be sufficient local health care expertise for patient care. As incidence decreases and complexity increases—particularly for rare metabolic diseases—services become more difficult to access. Developing resources to ensure that health care professionals are available locally, regionally, and nationally will be important to ensuring access to high-quality services.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

A basic cost-effectiveness assessment project was done to better inform the decision-making process. This assessment focused primarily on a scientific analysis of conditions and the features that should be considered when deciding whether they should be included in a newborn screening program, since costs often are the basis on which such decisions are made.

Costs and benefits related to screening for particular conditions or groups of conditions were evaluated after mapping them over major disease outcomes (e.g., life expectancy, cerebral palsy/stroke, seizures, developmental delay, hearing loss, vision loss). Costs were obtained from the literature and benefits determined from expected outcomes with and without early treatment or intervention. The results of these analyses indicate that most newborn screening programs improve outcomes and reduce overall costs. Further, technologies such as MS/MS or HPLC save money due to their multiplexing capabilities and low screening false-positive rates. The identification of potentially affected individuals at such an early time in life leads to many years over which the benefits accrue and aggregate over costs.

CONCLUSIONS

Significant variability in the conditions for which newborns are screened led to this project to assess the scientific and medical evidence and the views of the various individuals and interest groups related to conditions being considered. Throughout this undertaking, scientific literature and expert opinion formed the basis for information collection and assessment. The expert panel considered a range of information, from the disease-specific to the full breadth of the newborn screening system, in evaluating 84 conditions. There was an effort to overlay the evidence, where available, on top of expert opinion. The process of quantifying this expert opinion was informed by literature review and expert validation. It is important to acknowledge that there was limited scientific evidence available on the rare disorders considered by the expert panel. Further, because there was limited activity in the area of coordinated data collection and analysis, it seemed unlikely that robust scientific evidence would be available in the near future. Hence, reliance on experts and their ability to apply first principles was required.

Guiding principles for newborn screening and criteria for evaluating conditions were established. The conditions being considered were initially assigned through expert analysis to one of three categories, depending on how they met the screening criteria. The categories were core panel, secondary targets (conditions that are part of the differential diagnosis of a core panel condition), and not appropriate for newborn screening (either no newborn screening test is available or there is poor performance with regard to multiple other evaluation criteria).

Each condition was then evaluated to determine the extent to which the scientific evidence supports the availability of a test and a treatment, whether the natural history of the condition is well understood, and whether the information provided by testing indicates the possible presence of the condition or of a carrier state.

The expert panel identified 29 conditions for which screening should be mandated. An additional 25 conditions were identified because they are part of the differential diagnosis of a condition in the core panel or are clinically significant and revealed by the screening technology but lack an efficacious treatment (as with some identified through MS/MS technology) or because there are incidental findings for which there is potential clinical significance (hemoglobinopathies). The expert group thought it was important that such findings be communicated to the health care service community and to families. In addition, the view that the technologies employed in newborn screening be maximized is inherent in the recommendation that all clinically significant information discovered through newborn screening be provided to the relevant health care professionals and/or the family.

The expert group recommends that State newborn screening programs:

Mandate screening for all core panel conditions defined by this report;

Mandate reporting of all secondary target conditions defined herein and reporting of any abnormal results that may be associated with clinically significant conditions, including the definitive identification of carrier status;

Maximize the use of multiplex technologies; and

Consider that the range of benefits realized by newborn screening includes treatments that go beyond an infant’s mortality and morbidity.

The full breadth of the newborn screening system was assessed, including a brief review of its cost-effectiveness. Numerous barriers to implementation of an optimal screening and follow-up program were identified. Recommended actions to overcome these barriers include:

Establishment of a national role in the on-going scientific evaluation of conditions and the technologies by which they are screened;

Standardization of case definitions and reporting procedures;

Enhanced oversight of hospital-based screening activities;

Long-term data collection and surveillance; and

Consideration of the financial needs of programs.

Recommendations

Programs should continue to improve the components of the newborn screening system beyond the initial screening, communicate those results, and ensure that the newborn enters into short-term follow-up.

Result reporting procedures should be standardized.

Reports of confirmatory results should be obtained.

There should be improved oversight (e.g., Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospital Organizations (JCAHO) of hospital-based screening activities to improve tracking of screen-positive cases).

There should be more uniformity in the language and definition of the performance standards (e.g., repeat test, second test) monitored and reported by programs.

The quality assurance programs involving the diagnostic and follow-up system should be enhanced.

National oversight and authority with appropriate resources should be provided.

Systems should be in place for collection of data about individuals identified as screen-positive in newborn screening programs.