Abstract

Background

To determine the safety and tolerability of extended release niacin (ERN) in HIV-infected patients.

Methods

This was a pilot, open-label, 36 week study evaluating the safety and tolerability of ERN in HIV-infected patients with hypertriglyceridemia. Subjects with cardiovascular disease, diabetes or liver disease were excluded. Subjects with persistent elevation of triglyceride (TG) >200 after 8 weeks on American Heart Association Step One and Two Diets were started on ERN 500mg once daily, with continuation of the diet and exercise recommendations until the end of the study. ERN was increased by 500mg every 4 weeks, to a maximum of 1500mg/day, depending on subject tolerability. Safety and tolerability of ERN were assessed.

Results

Ten subjects enrolled received ERN. Dose titration and maintenance to 1500mg/day were achieved in all 10 subjects. No subject required dose adjustment. Mild flushing was experienced in 8 subjects. Asymptomatic hypophosphotemia was noted in 4 subjects; all resolved with oral phosphate supplementation. Median TG was reduced by 254 mg/dL (p<0.05). Non-significant changes were noted in liver enzymes, HDL, LDL, and total cholesterol. Fasting insulin and glucose levels did not change with treatment.

Conclusion

In this pilot study, ERN was well-tolerated and resulted in reduction of TG. Although the results of this study are promising, the study is limited in the small number of subjects. Further investigation is warranted.

Introduction

Abnormalities of lipid metabolism are common complications of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease and HIV therapy. Elevations in triglycerides (TG), low density lipoprotein (LDL), and total cholesterol are commonly seen in practice, particularly with the use of protease inhibitors (PIs). In a prospective study of 221 HIV-infected individuals followed for a median of 5 years, the incidence of new-onset hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia (HT) was 24% and 19%, respectively.1 The treatment of dyslipidemia in HIV-infected individuals is challenging. Results from the AIDS Clinical Trials Group study A5087 found monotherapy with either pravastatin or fenofibrate for dyslipidemia safe but unlikely to achieve the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) ATP III goals of the participants.2 Combination therapy of pravastatin and fenofibrate appeared safe but did not achieve NCEP lipid goals.

Niacin is a first line treatment for HT and hypercholesterolemia. Niacin inhibits the release of free fatty acids from adipose tissue, and increases lipoprotein lipase activity, which results in the increased removal of chylomicrons and TG.3 As a result, a smaller quantity of free fatty acids is transported to the liver. The liver, in turn, esterifies fewer fatty acids as triglycerides in very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL). The decreased production of VLDL leads to decreased generation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL). In addition, niacin enhances reverse cholesterol transport, resulting in increased concentrations of high-density lipoprotein (HDL). The benefits of niacin are that it can decrease total cholesterol by 10% and TG by 20–50%, while increasing HDL by 15–35%.4,5 LDL can be reduced by 10–25%.4 The effects of niacin on hormone sensitive lipase may concomitantly inhibit fat redistribution from peripheral to central adipose tissue.6 Niacin's benefit in preventing CAD has been verified in clinical trials.4

The concern of worsening glucose intolerance, flushing, and potential hepatotoxicity associated with immediate release niacin has limited its use in managing hypertriglyceridemia. The introduction of extended release niacin (ERN), which utilizes both conjugated and non-conjugated pathways of elimination, reduces the adverse effects commonly seen in immediate release niacin. There have been only a limited number of trials investigating the use of niacin in the HIV population.6–8 The advantageous effects of ERN make it attractive in the treatment of dyslipidemia for HIV-infected individuals. This study examined the safety and tolerability of ERN in HIV-infected individuals on stable highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) with HT.

Methods

This is an open-label pilot study that examined the safety and tolerability of Extended-Release niacin (Niaspan®) to treat hypertriglyceridemia in HIV-infected subjects receiving HAART regimens. Subjects were eligible for this study if they had 1) documented HIV-1 infection, 2) had an average elevated fasting TG level greater than or equal to 200 mg/dL by two serial screening blood tests one week apart, and 3) received the same potent antiretroviral therapy for at least 12 weeks prior to study entry. Potent antiretroviral therapy could be either an FDA approved regimen or an investigational new drug (IND) available in an IND program or expanded access program. This study was approved by the Committee on Human Studies of the University of Hawaii at Manoa and Queen's Medical Center. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Subjects were excluded if they had a history of type I or type II diabetes, coronary artery disease, or other lab criteria: hemoglobin < 9.1 g/dL for men and < 8.9 g/dL for women, absolute neutrophil count < 750 cells/mm3, platelet count < 75,000 platelets/mm3, aspartate aminotransferase [AST (SGOT)]/ alanine aminotransferase [ALT (SGPT)]/alkaline phosphate > 2.5 × upper limit of normal (ULN), creatinine > 2.0 × upper limit of normal, total bilirubin > 1.5 × ULN, history of acute or chronic pancreatitis, active peptic ulcer disease, active gallbladder disease, pregnancy, breast feeding, history of gout, history of any significant cardiopulmonary or renal disease, or if they were on other lipid lowering agents such as statins, fibrates, or other supplements. Subjects were also excluded if they had an infection or new medical illness within 14 days prior to study entry, unexplained fever >38.5°C within 14 days prior, documented or suspected acute hepatitis within 30 days prior to study entry, any malignancy, and if they had any history of hypersensitivity reaction to niacin or related products.

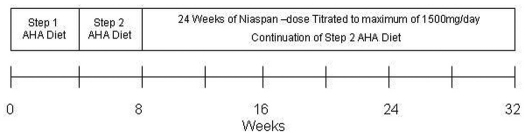

Eligible subjects were started on a American Heart Association (AHA) Step-One diet for 4 weeks. If the mean TG level was still greater than or equal to 200 mg/dL after four weeks on the Step-One diet, the dietary regimen was changed to a Step-Two diet. If the mean TG level was < 200 mg/dL the subject was discontinued from the study without further follow-up. A registered dietician instructed each subject on the guidelines for each STEP diet. Additionally, all subjects were told to follow AHA guidelines for exercise.

ERN was started on subjects with a mean TG level of ≥200 mg/dL after 4 weeks of AHA STEP-two diet. The initial dose of niacin was 500mg/day taken at bedtime. The daily dose of ERN was increased by 500 mg every 4 weeks, to a maximum of 1500 mg/day, depending on subject tolerability. The 1500 mg/day dose was sustained for the rest of the 36 week study. Subjects were followed every 4 weeks for a total of 32 weeks. Two lipid analyses were performed one week apart for each of the scheduled follow-up visits.

Safety was evaluated by summarizing the nature and rate of adverse events (signs and symptoms and laboratory values. Tolerability was evaluated by reporting on and summarizing dose modifications and dropouts. Elevations in liver function tests (primarily AST and ALT), changes in fasting glucose and insulin, and clinical symptoms (primarily gastrointestinal symptoms and flushing) were of particular interest. Insulin resistance was assessed using the Homeostasis Model of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) which is calculated by fasting insulin and glucose levels. The grading system utilized to quantify adverse events was the Division of AIDS Table for Grading Adult Adverse Experiences, Division of AIDS Regulatory Compliance.

Statistics

A descriptive analysis was performed evaluating the safety and tolerability of ERN over the course of the study. As this is a pilot study, an analysis for efficacy in lowering lipids was limited. An ad hoc analysis using the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was used to assess the changes in continuous variables over 32 weeks of diet and ERN therapy. Statistical significance was tested using a two-sided, α = 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and JMP version 5.1 (SAS, Cary, NC) statistical software packages.

Results

A total of 12 individuals were enrolled from August 2001 to November 2003. Of the 16 subjects screened, 12 subjects were enrolled. There were 11 male and 1 female subjects with an age range of 41–62. Ethnicity was predominately Caucasian with the exception of 1 Hispanic and 3 Asian subjects. Nine were on a PI based regimen, of which amprenavir (3 subjects), lopinavir (3 subjects) and nelfinavir (2 subjects) were predominately used. Three subjects were on efevirenz-based regimens. Two subjects were discontinued before the end of the study because of the following reasons: one achieved TG goals with diet and exercise interventions alone, and one was discontinued because of non-compliance with medication and follow-up visits (confirmed not to be due to adverse effects of ERN). Demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics of the 10 subjects who received ERN are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics of Subjects Who Received Diet Counseling and Extended Release Niacin

| Variable | Baseline (Before ERN) | End of Study (After 24 weeks of ERN) | p |

| N | 10 | 10 | |

| Age, years | 45.5 (42.8, 52.8) | 45.5 (42.8, 60.3) | |

| Ethnicity, Caucasian / Others | 7/3 | ||

| Gender, M/F | 10/0 | ||

| Weight (lbs) | 182.0 (158.9, 206.3) | 181.0 (157.5, 198.5) | NS |

| Heart Rate, pulse/min | 68.0 (60.5, 72.0) | 66.0 (54.5, 77.0) | NS |

| Systolic Blood Pressure, mm Hg | 122.0 ( 117.0, 129.5) | 125.0 (104.0, 130.0) | NS |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure, mm Hg | 82.0 (78.0, 88.0) | 82.0 (74.0, 83.5) | NS |

| CD4 count, cells/ml | 624.5 (422.8, 970.3) | 576.5 (319.8, 818.5) | NS |

| Undetectable HIV RNA viral PCR, n (%) | 6 (60%) | 7 (70%) | NS |

| Uric Acid, mg/dl | 5.5 (4.9, 6.5) | 5.2 (4.4, 6.7) | NS |

| Phosphorous, mg/dl | 2.6 (2.6, 3.0) | 3.1 (2.7, 3.6) | NS |

| Lactate, mg/dl | 1.6 (1.3, 2.0) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.0) | NS |

| Liver Function Tests | |||

| Aspartate aminotransferase, IU/l | 24.5 (21.3, 34.8) | 29.0 (21.0, 40.0) | NS |

| Alanine aminotransferase, IU/l | 25.0 (19.3, 29.8) | 27.0 (19.0, 47.0) | NS |

| Gamma glutamyl transpeptidase, IU/l | 40.5 (24.8, 70.8) | 38.5 (24.5, 50.0) | NS |

| Bilirubin, mg/dl | 0.6 (0.4, 1.0) | 0.8 (0.6, 0.8) | NS |

| Glucose Metabolism | |||

| Fasting glucose, mg/dl | 87.5 (76.3, 100.5) | 96.0 (76.5, 102.5) | NS |

| Fasting insulin, µUI/ml | 12.5 (8.3, 14.8) | 9.4 (6.0, 12.2) | NS |

| HOMA-IR, % | 2.7 (2.1, 3.9) | 2.3 (1.3, 2.3) | NS |

| Lipid Panel | |||

| Total Cholesterol, mg/dl | 279.0 (202.5, 319.5) | 248.0 (213.0, 271.3) | NS |

| High density lipoprotein, mg/dl | 31.0 (26.0, 40.0) | 33.5 (31.5, 47.0) | NS |

| Low density lipoprotein, mg/dl | 100.0 (63.0, 122.5) | 122.0 (81.3, 158.0) | NS |

| Triglyceride, mg/dl | 516.2 (281.0, 790.2) | 293.5 (219.3, 479.6) | <0.05 |

continuous variables shown as median (Q1,Q3) - compared by wilcoxon rank non-parametric testing

Of all 10 subjects who received ERN, all subjects were able to escalate their ERN dose to the targeted dose of 1500 mg per day. None of the subjects required any dose adjustment during the study. None of the subjects had a grade 3 or higher adverse event. The grade 2 or less adverse events are displayed in Table 2. Flushing, noted in 8 subjects, was the most common adverse symptom. All the symptoms of flushing were mild and none required pre-ERN aspirin therapy. Hypophosphotemia were noted in 4 individuals who required phosphate supplementation. The lowest phosphate level reported was 1.0 mg/dl. None of these subjects developed muscle related adverse effects such as rhabdomyolysis. One subject developed an episode of deep venous thrombosis and one subject developed a kidney stone which was assessed not to be related to study drug.

Table 2.

Adverse Events of Extended Release Niacin*

| Side Effect | Number of Subjects | Total number of episodes |

| Flushing | 8 | 18 |

| Diarrhea | 5 | 8 |

| Generalized Pain | 4 | 6 |

| Neuropathy | 2 | 3 |

| Chills | 2 | 2 |

| Numbness | 2 | 2 |

| Nausea | 2 | 3 |

| Sweats | 2 | 2 |

| Abdominal Pain | 1 | 1 |

| Cough | 1 | 1 |

| Edema | 1 | 1 |

| Fever | 1 | 1 |

| Itching | 1 | 1 |

| Muscle Cramps | 1 | 1 |

| Headache | 1 | 1 |

| Dizziness | 1 | 1 |

| Confusion | 1 | 1 |

| Dermatitis | 1 | 1 |

| Acid Reflux | 1 | 1 |

There was no grade 3 or higher adverse events

No significant differences in CD4 counts were noted before and after the study (median change (Q1, Q3) of − 23 cell/mm3 (−79.0, 110.0)). No difference in AST or ALT were noted [AST median change (Q1, Q3) of 5.2 IU/L (−9.3, 11.5) and ALT median change (Q1,Q3) of 6.2 IU/L (3.1, 18.4)]. No difference in HOMA-IR were found (median change (Q1, Q3) of −0.8 (−1.3, 0.9). Median change (Q1, Q3) in fasting insulin of −2.0 µUI/mL (−8.0,−1.7) and glucose of 8.3 mg/dl (−5.3, 11.4) were noted, neither of which were statistically significant. Changes in laboratory data before and after ERN therapy is provided in Table 1.

Median TG (Q1, Q3) were reduced by 254 mg/dL (81.4, 614.9) (p<0.05) with a median % reduction of 46.6% (26.7, 63.0). The HDL median change (Q1, Q3) was 5.0 mg/dL (1.0, 8.0) (p=0.26), while the LDL median change (Q1, Q3) was 9 mg/dL (−14.0, 17.0) (p=0.09) and the total cholesterol median change (Q1, Q3) was −25 mg/dL (−41.2, 30.2) (p=0.50).

Discussion

This pilot study suggests that a regimen of diet and ERN for treatment of HT in HIV infected subjects is well tolerated. All subjects were able to achieve the targeted ERN dose without significant development of adverse events. The symptom of flushing was the most common side effect. The total number of episodes of flushing in the 24 weeks of therapy for 8 subjects was 18. This percentage of subjects experiencing flushing is consistent with earlier studies.5,9 The symptoms of flushing appear to be tolerable. Interestingly, none of the subjects required premedication with aspirin to reduce flushing.

The concern for worsening glucose metabolism was not seen in our study. This study did not show significant increases in fasting glucose or insulin levels, and the HOMA-IR measures were similar between baseline and end of study. Our findings are consistent with the Assessment of Diabetes Control and Evaluation of the Efficacy of Niaspan Trial (ADVENT) study, where niacin was safely used in diabetic subjects.10 This 16 week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 148 subjects randomized into either placebo or ERN arms with dosages of 1000mg and 1500mg did not show significant changes in gylcemic control.

Liver function tests and insulin sensitivity were not significantly impacted in our study. The lack of hepatotoxicity or change in glycemic control may have been due to the lower dosage used. However, our target dose was still within the normal therapeutic range. Hypophosphotemia was common but did not result in significant clinical and laboratory abnormalities.

This study did show a significant 47% reduction in triglycerides, but no significant changes in HDL, LDL or total cholesterol. These changes were similarly noted in the ACTG Study A5148.8 The lack of response in LDL, total cholesterol and HDL may be due to limited sample size and/or drug exposure, or influence of HIV and HAART. Although significant reductions in TG were found, the clinical implication of this reduction is unclear. While cardiovascular risk is associated with low HDL and high LDL and triglycerides, the actual cardiovascular risk from secondary dyslipidemia due to HIV and /or HAART is still not well understood.

Limitations of this study include a small sample size, lack of a control group, and inclusion of relatively healthy subjects. However the objective of this pilot study was to determine if ERN is safe in the HIV infected population. The close follow-up and duration of this study would have been long enough to detect acute changes in glucose metabolism, liver enzyme function and clinical symptoms such as gastrointestinal symptoms and flushing. Further investigation is warranted to determine the safety, tolerability and efficacy in HIV-infected patients with impaired glucose tolerance, dyslipidemia, and poor virologic control.

In this pilot study, ERN was well tolerated and resulted in reduction of TG. All subjects were able to achieve the targeted ERN dose without significant development of adverse events. Flushing and gastrointestinal symptoms were tolerable. Hypophosphotemia was common but did not result in significant clinical and laboratory abnormalities. Liver function tests and insulin sensitivity were not significantly impacted. Although the results of this study are promising, the study is limited in the small number of subjects. Further investigation is warranted.

Figure 1.

Schema of Study Interventions

Acknowledgements

The study team wishes to sincerely thank Debbie Ogata-Arakaki RN, Hawai'i Center for AIDS and all the subjects who participated in the study. This investigation was supported by a grant from the Queen Emma Foundation (SCR2000-12), Honolulu, HI. Study medication was provided by KOS pharmaceuticals, Inc. KOS pharmaceuticals did not have any influence on the design and conduct of the study; the collection or interpretation of the data; the development of the analysis plan; the preparation and conduct of the analysis; or the drafting, critical revision, or approval of the final manuscript. This manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Queen Emma Foundation or KOS pharmaceuticals, Inc. The JMP statistical software license was supported by NIH Grant number RR-16467 from the HS-BRIN program of the National Center for Research Resources. The following investigators were supported in part by grants through the Clinical Research Education and Career Development (CRECD) in Minority Institutions: D Chow (R25 RR019321).

References

- 1.Tsiodras S, Mantzoros C, Hammer S, Samore M. Effects of protease inhibitors on hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and lipodystrophy: a 5-year cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(13):2050–2056. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.13.2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fichtenbaum CJ, Gerber JG, Rosenkranz SL, et al. Pharmacokinetic interactions between protease inhibitors and statins in HIV seronegative volunteers: ACTG Study A5047. AIDS. 2002;16(4):569–577. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203080-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knopp RH. Clinical profiles of plain versus sustained-release niacin (Niaspan) and the physiologic rationale for nighttime dosing. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82(12A):24U–28U. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00847-9. discussion 39U–41U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caceres CA, Enslein K. Coronary drug project. JAMA. 1978;239(25):2655–2656. doi: 10.1001/jama.239.25.2655b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guyton JR. Effect of niacin on atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82(12A):18U–23U. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00767-x. discussion 39U–41U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fessel WJ, Follansbee SE, Rego J. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol is low in HIV-infected patients with lipodystrophic fat expansions: implications for pathogenesis of fat redistribution. AIDS. 2002;16(13):1785–1789. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200209060-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aberg JA, Zackin RA, Brobst SW, et al. A randomized trial of the efficacy and safety of fenofibrate versus pravastatin in HIV-infected subjects with lipid abnormalities: AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study 5087. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2005;21(9):757–767. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dube MP, Wu JW, Aberg JA, et al. Safety and efficacy of extended-release niacin for the treatment of dyslipidaemia in patients with HIV infection: AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study A5148. Antivir Ther. 2006;11(8):1081–1089. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capuzzi DM, Guyton JR, Morgan JM, et al. Efficacy and safety of an extended-release niacin (Niaspan): a long-term study. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82(12A):74U–81U. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00731-0. discussion 5U–6U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grundy SM, Vega GL, McGovern ME, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of once-daily niacin for the treatment of dyslipidemia associated with type 2 diabetes: results of the assessment of diabetes control and evaluation of the efficacy of niaspan trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(14):1568–1576. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.14.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]