Abstract

Background:

There is no study available on the frequency, predisposing factors and outcome of needle stick injury (NSI) in cytopathologists who perform fine needle aspiration (FNA).

Aim:

To know the frequency, circumstances and sequlae of NSI sustained by cytopathologists, assess their knowledge about risks of NSI and attitudes and practices towards use of standard precautions and post-injury wound care.

Materials and Methods:

Study design: cross sectional. Setting: Tertiary care teaching and non-teaching hospitals and private laboratories. Data collection method: Knowledge, attitude and practices survey using a questionnaire.

Results:

Majority (90.5%) of the respondents have had NSI in their total career. In the previous year, more than half (71.4%) had at least one NSI (mean 3.2). NSI was the most common in index finger of non-dominant hand (59.6%) and occurred during step two of FNA procedure when the needle was being manipulated within the lump. The major predisposing factors were uncooperative patients (88.9%), small children (54%), deep masses (36.5%), hot humid climate (88.9%), heavy workload (76.2%) and poor administrative arrangement (54%). The adherence to standard precautions was not optimal (74.6%). None of them reported NSI to the authorities, nor investigated source patient or themselves. 82.5% of the respondents were not aware of any formal exposure reporting system in their hospital.

Conclusion:

Cytopathologists frequently experience NSI while performing FNA. Frequency of injury is also related to patient characteristics and work site factors. Education and motivation for adhering to standard precautions and post-exposure prophylaxis are often lacking.

Keywords: Cytopathologist, fine needle aspiration, needle stick injury, occupational hazard

Introduction

The fine needle aspiration (FNA) procedure involves use of sharp, hollow, thin bore needle and handling of contaminated needle. This exposes to the risk of transmitting human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B (HB) and hepatitis C (HC) infections through needle stick injuries (NSI).[1] To the best of our knowledge there is no study available in the literature on the incidence, predisposing factors, and outcome of NSI amongst cytopathologists who perform FNA on a daily basis in busy clinics. Cytopathologists remain an under recognized group of health care workers in relation to risk of NSI possibly due to under reporting.

The present study was carried out to know the frequency, circumstances and sequlae of NSI sustained by cytopathologists during FNA. Their knowledge about risks after NSI and attitudes and practices towards use of standard precautions and post-injury prophylactic measures were also assessed. The aim was to identify risk factors predisposing to NSI and specific needs of this group of health care providers for pre and post exposure prophylaxis (PEP). This can help policy planners and administrators to adopt specific preventive strategies and to improve infection control practices and strengthen post injury prophylaxis in this group.

Materials and Methods

Sixty-three pathologists performing FNA procedure in teaching, non-teaching institutions and private laboratories in urban areas of New Delhi were interviewed through a cross sectional knowledge, attitude and practices (KAP) survey. The questionnaire was pilot tested in a teaching hospital and revised. The questionnaire was filled by the respondents. The questions included information about their practices in FNA procedure, experience of NSI, predisposing factors to NSI like patient and FNA target characteristics, staffing conditions, work load, post injury care, compliance with standard precautions and perception on post-NSI risks.

Results

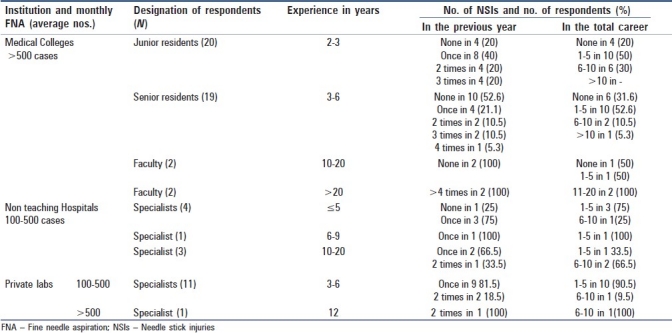

Response rate was 78.7% as 63 out of 80 returned questionnaires. Respondents’ characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were 66.7% (42) females and 33.3% (21) males. The age range was 25-57 years and experience in FNA ranged from 2 to 27 years (mean 6.3 years). 68.2% (43) of the respondents were from teaching institutions having heavy average monthly FNA load of >500 cases. In these institutions, residents and faculty perform FNA on rotational basis and get average of 4 months in a year. However, non-teaching specialists and private practitioners regularly do FNA procedure and their workload is low.

Table 1.

Respondents’ characteristics and number of NSIs in the previous year and in total career

A large proportion 90.5% (57) of the respondents have had NSI in their total career and only 9.5% (6) of them had not experienced it so far as shown in Table 1. Majority 61.4% (37 out of 57) had experienced one to five NSIs (range being 0-20). In the previous year, more than half 71.4% (45) had at least one NSI (mean 3.2) and 28.6% (18) did not experience any NSI.

As needle is held in dominant hand (right in most cases), left hand is used to fix the lump. NSI was commonest in non dominant hand i.e. left in 52.4% (33 out of 57) and right in 22.2% (14 out of 57). Both hands were injured in 14.3% (9 out of 57). Index finger was the most commonly injured site in 59.6% (34 out of 57) followed by middle finger in 21.1% (12 out of 57), thumb in 8.8% (5 out of 57), palm in 7% (4 out of 57) and ring finger in 3.5% (2 out of 57). Most 92% (52 out of 57) of them were right-handed people.

61.9% (39) respondents opined that frequency of injury decreased with increasing proficiency while 38.1% (24) did not think so. Table 1 shows that 80% (16 out of 20) of junior residents had sustained NSI as compared to 68% (13 out of 19) of senior residents. This difference is not significant ( Fisher's exact test, P value=0.4801).

The major patient-related risk factors predisposing to NSI as perceived by the respondents were uncooperative patients 88.9% (56), small children 54% (34), deep masses 36.5% (23), poorly accessible site like axillary node 11.1% (7) and small size of swelling 9.5% (6). In addition work and environment related factors identified were hot humid climate 88.9% (56), heavy workload 76.2% (48) and poor administrative arrangement 54% (34) which add to the risk by causing fatigue and often slipping of the syringe due to humid hands. Although 85.7% (54) respondents thought that sex of the patient does not affect chances of injury but 14.3% (9) thought it to be more with female patients as they are more apprehensive and sensitive.

Half (50.8%) (32) of the respondents felt that there are more chances of NSI with suction technique, 15.9% (10) felt it to be more with non suction technique, 17.5% (11) had found no difference and 15.9% (10) could not specify. Use of non-suction technique for FNA of cystic swellings resulted in muco-cutaneous exposure via splash of cyst fluid to the eyes and mouth in 27% (17) respondents. Often this fluid contained blood.

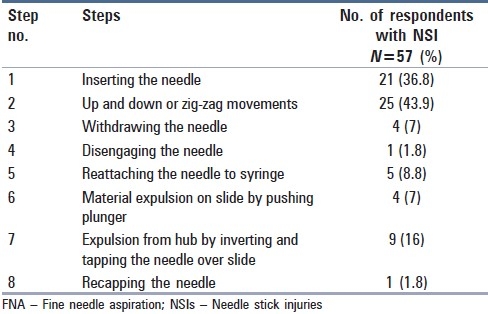

Table 2 shows the occurrence of NSI with different steps of FNA in 57 respondents who had NSI at least once. The first two steps in FNA procedure contributed to majority 80.7% (46 out of 57) of NSI. Maximum 43.9% (25 out of 57) chances of injury were with step two when the needle was in the lump and being moved in zig-zag motion.

Table 2.

Risk of Needle stick injury with different steps of FNA

Majority 93.7% (59) felt that NSI can lead to all three infections, i.e. hepatitis B, C and HIV, while 4.8% (3) thought that NSI posed risk of hepatitis B and HIV infection. One respondent also feared about local bacterial infection. 93.7% (59) felt that these types of injuries are serious and need some post-injury care, while 6.3% (4) thought they were routine and did not need any attention. Two had developed HB which they attributed to NSI, but it was not investigated. Most 96% (55) of the respondents did not develop any clinical symptoms or signs of these infections nor volunteered for testing for them.

Regarding pre-FNA prophylaxis most 88.9% (56) recommended that all cytopathologists engaged in performing FNA is high risk group and should be vaccinated against HB. In addition, 93.7% (59) also felt that they also should be screened for HB, HC and HIV especially after NSI or if resources permit as a routine at a regular interval. It is noteworthy that majority 79.4% (50) had received all three doses of HB vaccine, 15.9% (10) had received two doses and 4.8% (3) had received none.

All respondents always use disposable needles and 88.9% (56) of them use gloves while performing FNA and 11.1% (7) do not use gloves because gloves interfere in lump palpation and fixation. Most 79.4% (50) take history of any prior infection with HB, HC and HIV. All except one avoided needle recapping. All practiced routine hand washing with soap and water after FNA. However, 16% (10) from a teaching hospital pointed out that running tap water was often not available and proper washing was not possible with stored water or small quantity of water. 74.6% (47) felt that adherence to standard precautions is not optimal due to various reasons such as perceived low risk of exposure, patient was not known positive for HB, HVC or HIV, forgot in work pressure due to heavy work load and practicing in under resourced setting.

None of them reported any NSI to the hospital authorities, investigated source patient or themselves or demanded any PEP care from hospital because they thought since patient was not a known positive for HB or HIV, it did not pose a risk. It is serious to note that 82.5% (52) of the respondents were not aware of existence or non-existence of a formal exposure reporting system in their hospital. None except one of the institutions had any ready kit available for NSI wound care in FNA clinic. There were no posters or communication material to sensitize aspirators on infection control procedures and post NSI prophylaxis.

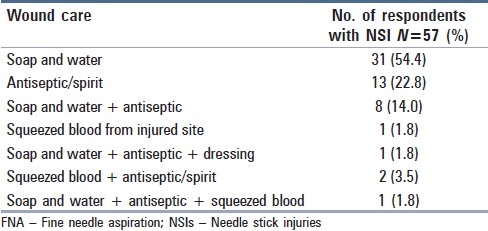

Table 3 shows different management of NSI wound done by 57 respondents who had experienced NSI. Majority 54.4% (31) washed injury with soap and water, 22.8% (13) applied antiseptic or spirit, 14% (8) used both soap and water followed by antiseptic. 44% (28) considered these measures were adequate to reduce the risk of transmission of any infection, 24% (15) thought that it was not sufficient and more guidelines should be available and 11% (7) were not sure on the role of these measures.

Table 3.

Care of needle stick injury wound by respondents

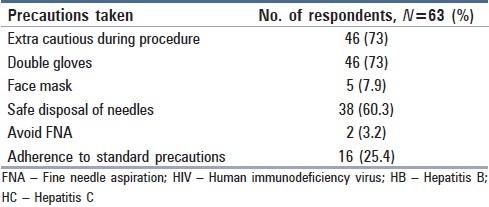

FNA practices in high-risk patients are shown in Table 4. Only 73% (46) were extra cautious in HB, HC and HIV infected patients and used double gloves. Only 7.9% (5) used face mask. Two even felt that it is best to avoid FNA in such patients.

Table 4.

FNA practices among cytopathologists in patients known positive for HIV/HB/HC

Discussion

The present study evaluated knowledge, attitude and practices of cytopathologists in different work settings and at different levels of work load and skills. Although relying on recall memory, this study demonstrates that NSI occurs frequently (average 3.2 in one year) amongst cytopathologists in various settings. Injury rates differ depending on the frequency of performing FNA. Number of centres performing FNA in India is increasing sharply. As of 1998, 56% of labs performed >1000 cases per year and in 46% of centres pathologists alone perform FNA.[2] Disposable needles and syringes are used in all centres. Syringe holders are used in 61% centres which gives more stability to hands while aspirating.[2]

Due to economic constraints, the patients who are referred for FNA are not screened for HB, HC and HIV infections. FNA is usually the first line of investigation and HB and HIV status is usually unknown. A high frequency of NSI amongst respondents who perform FNA in patients with uncertain status regarding HIV and HB and HC infections makes cytopathologists a high risk group who requires pre and post injury prophylaxis. This risk will increase with rising trends of HIV, HB and HC infections. Case reports on transmission of mycobacterium tuberculosis, dengue virus and malaria are also worth mentioning considering high prevalence of these in India.[3–6]

Senior residents were less likely to get NSI as compared to junior residents as they develop proficiency with time. However, the difference was not significant. The number in each group of respondents in different proficiency level was small to demonstrate meaningful difference. It is also interesting to note [Table 1] that senior faculty and senior specialists (skilled operators) sustained more injuries as they get to do all referral cases which are difficult, i.e. failed FNA by residents, uncooperative patients, small children, unapproachable lumps, etc. A study in Uganda teaching hospital showed that Interns suffered more NSI than any other occupational group.[7] Formal training in procedural skills can be effective in improving competence and confidence and reducing the risk of sustaining NSI.[8,9]

The FNA technique involves use of hollow bore needles. NSI with hollow bore needles are more risky as transmission of HC and HIV is high compared with other sharps since more blood is transferred by hollow needles.[10]

Maximum accidental NSI during FNA occurred during up and down or zig-zag movements of needle. The other steps of FNA, i.e. inserting the needle, withdrawing the needle, disengaging the needle also contributed to a significant risk. This procedural risk cannot be completely eliminated but reduced in non-suction technique due to omission of step 4, i.e. disengaging the contaminated needle from the syringe. Moreover non-suction technique cannot be applied to all types of lumps especially in cystic swellings there is risk of muco-cutaneous exposure via splash. The potential risk from muco-cutaneous exposure to cyst fluids has not been assessed but can be potentially infectious as it often contains blood.

Modifying the syringe to reduce handling of contaminated needle and development of new devices to take up the function of fingers for stabilization of the target lesion providing safety for aspirator seem to be good options.[11–14] In a modified method of FNA, the procedure is initiated with 2 cc of air in the syringe. At the end of aspiration the residual air can be used to empty the needle without its manipulation.[15] However, no more studies are available on the application and utility of these devices or modifications and the risk of NSI by these methods has not been widely assessed.

The patient-related predisposing factors are also unavoidable, e.g. small lumps are difficult to fix and slip between hands, uncooperative patient moves during procedure, small children and female patients are more likely to be apprehensive and uncooperative. The working conditions like understaffing, heavy work load, inadequate administrative support, etc. were considered to be contributing to the risk of NSI by the majority of respondents. This underscores the importance of administrative measures. Poor organizational climate and high workloads were associated with twofold increase in the likelihood of NSI to hospital nurses.[16]

Adherence to standard precautions during and after FNA procedure was low (25.4%) amongst the cytopathologists which could put them and patients at greater risk of acquiring HIV and other infections. The potential preventive approaches include development of best practice guidelines for safe FNA procedure, training and facilities for standard precautions and monitoring adherence to standard precautions and research and development of safer FNA devices and their widespread implementation.[17,18] HB immunization of all cytopathologists should be implemented. It bears reiteration that no safety device is foolproof and commonsense and caution is paramount.

Varying practices for NSI wound management and uncertainty about the role of antiseptics amongst our respondents calls for provision of consensus guidelines in FNA clinic. Some recommend prompt application of topical disinfectant, but WHO recommends wound washing with soap and water only. Squeezing and expelling blood from injured site has also no role. Use of antiseptics is not contraindicated but there is no evidence that use of antiseptics, and squeezing the wound reduce the risk of blood-borne pathogens transmission. Use of disinfectants and bleach is not recommended on skin.[10,19,20]

There is a poor knowledge of post-exposure prophylaxis. Education and facilities for effective timely prophylaxis are needed. As regular screening of all staff is not possible due to limited resources in developing countries but focusing on those at risk may be warranted. Active surveillance, analysis of injury data and periodic review of interventions are important in targeted high-risk occupational groups, especially when the workforce has a high turnover, as is typical in teaching hospitals.[21–23]

To conclude, our study shows that the occupational exposure to potentially infected blood, tissue and body fluid occurs regularly amongst cytopathologists performing FNA. Less-skilled aspirators were more likely to get injured. Frequency of injury is also related to patient characteristics and work site factors where facilities, education and motivation for adhering to standard precautions and post-exposure prophylaxis are often lacking.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Sharma R, Rasania SK, Verma A, Singh S. Study of prevalence and response to needle stick injuries among health care workers in a tertiary care hospital in Delhi, India. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:74–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.62565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das DK. Fine-needle aspiration cytology: its origin, development, and present status with special reference to a developing country, India. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;28:345–51. doi: 10.1002/dc.10289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oymak SF, Gulmez I, Demir R, Ozesmi M. Transmission of mycobacterium tuberculosis by accidental needle stick. Respiration. 2000;67:696–7. doi: 10.1159/000056304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris SH, Khan R, Verma AK, Ahmad S. Finger ulceration in a healthcare professional. Ann Afr Med. 2010;9:45–7. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.62626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langgartner J, Audebert F, Scholmerich J, Gluck T. Dengue virus infection transmitted by needle stick injury. J Infect. 2002;44:269–70. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2002.0994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tarantola A, Rachline A, Konto C, Houze S, Sabah-Mondan C, Vrillon H, et al. Occupational Plasmodium falciparum malaria following accidental blood exposure: a case, published reports and considerations for post-exposure prophylaxis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2005;37:131–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newsom DH, Kiwanuka JP. Needle-stick injuries in an Ugandan teaching hospital. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2002;96:517–22. doi: 10.1179/000349802125001186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liddell MJ, Davidson SK, Taub H, Whitecross LE. Evaluation of procedural skills training in an undergraduate curriculum. Med Educ. 2002;36:1035–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitby RM, McLaws ML. Hollow-bore needlestick injuries in a tertiary teaching hospital: epidemiology, education and engineering. Med J Aust. 2002;177:418–22. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated U.S. Public Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to HBV, HCV and HIV and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001;50:1–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsang WY, Chan JK, Chan SK. Fine-needle aspiration anchor.A simple device to prevent needle-stick injury at fine-needle aspiration. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1993;117:1047–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halsell RD. Modification of a syringe for aspiration biopsy. Radiology. 1993;189:614. doi: 10.1148/radiology.189.2.8210397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim E, Acosta E, Hilborne L, Phillipson J, DeGregorio F, Liu P, et al. Modified technique for fine needle aspiration biopsy that eliminates needle manipulation. Acta Cytol. 1996;40:174–6. doi: 10.1159/000333684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sibbitt RR, Palmer DJ, Bankhurst AD, Sibbitt WL., Jr Integration of new safety technologies for needle aspiration of breast cysts. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279:285–92. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0710-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galed-Placed I, Pértega-Díaz S, Pita-Fernández S, Vázquez-Martul E. Fine needle aspiration cytology without needle manipulation to reduce the risk of occupational infection in healthcare personnel. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26:336. doi: 10.1086/503511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. Effects of hospital staffing and organizational climate on needlestick injuries to nurses. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1115–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.7.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jahan S. Epidemiology of needlestick injuries among health care workers in a secondary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2005;25:233–8. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2005.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trape-Cardoso M, Schenck P. Reducing percutaneous injuries at an academic health center: a 5-year review. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32:301–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilburn SQ, Eijkemans G. Preventing needlestick injuries among healthcare workers: A WHO-ICN collaboration. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2004;10:451–6. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2004.10.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasting G, Rollin PE. Wound care following needlestick injuries. JAMA. 1997;277:517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia and Regional Office for Western Pacific, SEARO regional publication no 41. WHO practical guidelines for infection control in health care. 2004.

- 22.Bodkin C, Bruce J. Health professionals’ knowledge of prevention strategies and protocol following percutaneous injury. Curationis. 2003;26:22–8. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v26i4.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chogle NL, Chogle MN, Divatia JV, Dasgupta D. Awareness of post-exposure prophylaxis guidelines against occupational exposure to HIV in a Mumbai hospital. Natl Med J India. 2002;15:69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]