Abstract

Background

The use of smartphones and their associated applications (apps) provides new opportunities for physicians, and specifically orthopaedic surgeons, to integrate technology into clinical practice.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was twofold: to review all apps specifically created for orthopaedic surgeons and to survey orthopaedic residents and surgeons in the United States to characterize the need for novel apps.

Methods

The five most popular smartphone app stores were searched for orthopaedic-related apps: Blackberry, iPhone, Android, Palm, and Windows. An Internet survey was sent to ACGME-accredited orthopaedic surgery departments to assess the level of smartphone use, app use, and desire for orthopaedic-related apps.

Results

The database search revealed that iPhone and Android platforms had apps specifically created for orthopaedic surgery with a total of 61 and 13 apps, respectively. Among the apps reviewed, only one had greater than 100 reviews (mean, 27), and the majority of apps had very few reviews, including AAOS Now and AO Surgery Reference, apps published by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and AO Foundation, respectively. The national survey revealed that 84% of respondents (n = 476) have a smartphone, the majority (55%) have an iPhone, and that 53% of people with smartphones already use apps in clinical practice. Ninety-six percent of respondents who use apps reported they would like more orthopaedic apps and would pay an average of nearly $30 for useful apps. The four most requested categories of apps were textbook/reference, techniques/guides, OITE/board review, and billing/coding.

Conclusion

The use of smartphones and apps is prevalent among orthopaedic care providers in academic centers. However, few highly ranked apps specifically related to orthopaedic surgery are available, and the types of apps available do not appear to be the categories most desired by residents and surgeons.

Introduction

The use of mobile phones to assist the practice of orthopaedic surgery has been examined, but the development of smartphones has created new opportunities to integrate mobile technology into daily clinical practice [2, 6, 9]. A smartphone is a cellular telephone with an integrated computer that is capable of performing a broad array of tasks, including running various downloadable applications (apps) that typically are not associated with a cellular phone. Although smartphones existed as early as 1992, it was not until the development of the Palm and Blackberry in 2001 and 2002, respectively, that consumers began to use mobile devices capable of wireless information services and web browsing [11]. Release of the iPhone in 2007 included features not found on previous devices and led the way for developers to create a library of apps available to consumers.

A smartphone is defined by its manufacturer or operating system (OS), and the current leading systems run Blackberry, iPhone, and Android platforms. As of July 2010, the distribution of smartphone operating system market share in the United States for Blackberry, iPhone, and Android were 39%, 24%, and 17%, respectively [7]. Most currently available smartphones incorporate a touch-screen display, wireless internet capability, audio and video media storage and playback functions, and the ability to download and install custom apps in a device small enough to fit in a pocket. Owing to their portability, ability to update, speed, and simplicity, smartphone apps are an ideal tool for quick reference or when accessing a desktop computer would not be feasible. As a result, smartphones can serve as a quick reference tool for medical students, residents, fellows, and surgeons. As of September 2010, Apple’s online digital “App Store” proclaimed to have more than 200,000 apps “to make the iPhone even better” [1]. In the Apple app store, medical apps have been one of the fastest growing categories of programs and include various programs designed specifically for orthopaedic surgeons [11, 16]. More importantly, smartphone app stores provide the ability for surgeons and professional software developers to create novel tools to assist surgeons in practice and education.

Despite the widespread prevalence of smartphones and apps available for general utilities, and even specifically for physicians, few apps are designed for orthopaedic surgeons [8]. Ways in which technology can be successfully integrated into an orthopaedic practice have been described [2, 3, 12, 15], and the literature suggests that other medical specialties have embraced the use of smartphones and mobile apps [5, 11]. However, no study to date has specifically evaluated the use of smartphone apps in orthopaedic surgery or evaluated the specific desires and smartphone functions that cater to orthopaedic surgeons for use in clinical practice.

The purposes were (1) to review all smartphone apps available for the five most popular operating systems (Blackberry, iPhone, Android, Palm, and Windows) and (2) survey orthopaedic surgeons, fellows, and residents to determine the types of apps that would be most useful to practicing orthopaedic clinicians.

Materials and Methods

Smartphone apps specifically targeted to orthopaedic surgeons were identified twice, first in August 2010 and again in April 2011, to allow for comparison. Each of the five current popular smartphone operating systems has a respective app store to browse and download supplemental programs for use on the devices. Each app store was queried with a combination of the following terms: orthop(a)edic(s), ortho, surgery, musculoskeletal, bones, and fracture. Typically, the app store includes a brief summary of the app (provided by the developer), posts reviews from individuals who have purchased the app, and lists the cost of the app. A complete list was generated for each phone OS, and the summary of each app was reviewed. Information was recorded for each app including ratings, number of ratings, publisher information, categorization of app type, and cost. Data were grouped and summarized for clarity.

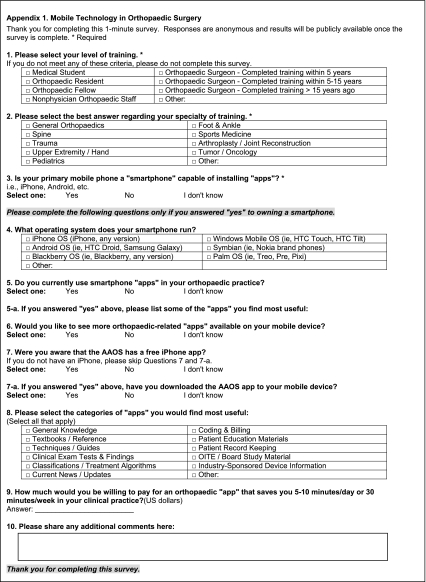

A survey of ACGME-accredited orthopaedic training programs was conducted through an online survey distributed via email in August 2010. Contact information for all current orthopaedic training programs was obtained via the ACGME website and an email was distributed to all program coordinators and directors requesting their participation (total of 311 emails sent). IRB approval was obtained for the study design, and a brief explanation regarding the purpose of the survey was provided to participants in the email. Participants could review the survey before submitting, and submitting results constituted consent to participate in the study. The email requested that the survey information be forwarded to all residents, fellows, and attending surgeons in each department. Two additional reminder emails subsequently were sent to increase the survey response rate.

The design of the survey emphasized brevity to increase response rates and was designed in accordance with previously published recommendations [14]. The survey consisted of nine questions and required approximately 1 to 2 minutes to complete (Appendix 1). In addition, the survey could be completed directly from the email request or via a provided hyperlink to an internet web form. A field was left for additional comments from respondents. Responses were summarized and evaluated. A total of 476 complete responses were obtained. Limited demographic data were collected to minimize the length of the survey and increase the response rate.

Results were tabulated using Excel 2007 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA), and data are presented as means where appropriate. Because of the descriptive nature of this study, no comparisons were made between results.

Results

A query of the iPhone app store yielded a total of 61 apps that met the criteria listed above, and review of the Android app store yielded 13 relevant apps, eight of which were duplicates of apps available for the iPhone. Review of the Blackberry, Palm, and Windows Mobile app stores yielded no relevant apps. Among the list of iPhone apps surveyed, 37 (60%) had been released or updated in the previous 6 months, and six had been updated/released in the prior 2 weeks. However, only 30 apps had greater than five reviews (49%), and only 17 (28%) had greater than 10 reviews. The apps with greater than 10 reviews were further analyzed, and a comparison was performed between their rankings in April 2011 versus August 2010 (Table 1). Of the top 10 apps ranked by popularity in August 2010, eight remained in the top 10 list 8 months later in April 2011. With the exception of one app that had 733 ratings (iOrtho), the next most numerous rated app had only 90 ratings (SpineDecide). For the 61 apps, there were only 37 unique developers creating apps specifically targeting orthopaedic surgeons. The average cost for all apps was $12.85, but after excluding the 11 free apps, the average cost for paid apps was $22.39 (range, $0.99–99.99). Of all apps, 32 (52%) were clinically oriented, 16 (26%) were educationally oriented, seven (11%) were focused on industry/news, and six (10%) were designed for patients. Further categorization revealed 11 technique guides; nine reference apps; seven industry/news apps; six flashcard apps; five designed for patient information; four each focused on billing, clinical assessment, clinical examination, contact information, and radiology; two textbooks; and one app designed for patient record keeping.

Table 1.

Orthopaedic apps with more than 10 ratings from the Apple app store

| Name/category | Price | Release date | Rating | Rank (4/11) | Rank (8/10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAOS Now*/News | free | 3/7/2010 | 4 | 10 | 11 |

| AO Surgery Reference/Clinical (technique guide) | free | 2/23/2011 | 4 | 15 | – |

| CORE – Clinical Orthopedic Exam*/Clinical (exam) | $39.99 | 12/16/2010 | 4.5 | 7 | 5 |

| iOrtho*/Clinical (exam) | free | 9/3/2010 | 1.5 | 1 | 1 |

| iSpineCare/Education (patient) | $59.99 | 12/21/2010 | 4 | 11 | 13 |

| KneeDecide MD/Patient Oriented | $4.99 | 2/8/2011 | 4.5 | 16 | – |

| Mobile Coder Foot & Ankle/Clinical (billing) | free | 3/9/2011 | 3 | 12 | – |

| Mobile Coder Orthopedics/Clinical (billing) | free | 3/14/2011 | 2.5 | 5 | 7 |

| Mobile OMT Upper Extremity/Clinical (technique) | 29.99 | 1/10/2011 | 5 | 13 | – |

| OrthoAnatomy – Brancel*/Clinical (reference) | $2.99 | 2/8/2011 | 3 | 14 | 15 |

| OrthoFind/Patient Oriented | free | 11/29/2010 | 2.5 | 9 | 8 |

| Orthopedics Hyperguide/Educational (reference) | free | 1/4/2011 | 2.5 | 3 | 3 |

| Scoligauge/Clinical (exam) | $0.99 | 3/7/2011 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| ShoulderDecide MD/Patient Oriented | $4.99 | 2/9/2011 | 5 | 17 | – |

| SLIC/Clinical (reference) | free | 1/29/2010 | 2.5 | 8 | 6 |

| Smith & Nephew Mobile/Industry/News | free | 12/19/2010 | 3 | 6 | 4 |

| SpineDecide/Education (patient) | $4.99 | 3/2/2011 | 3.5 | 2 | – |

(4/11) reflects popularity ranking in April 2011 and (8/10) reflects ranking in August 2010. Dashes indicate that the app was not available in August 2010. Mean ratings are shown based on a 1–5 scale (1 = low, 5 = high). An asterisk (*) indicates apps that are also available for the Android platform.

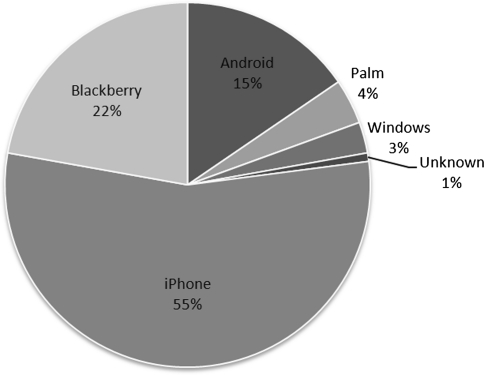

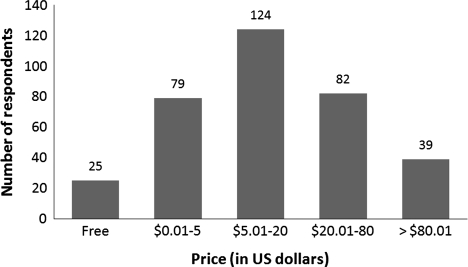

The distributions of iPhone, BlackBerry, and Android operating systems among the 476 survey respondents with a smartphone were 55%, 22%, and 15%, respectively (Fig. 1). Eighty-four percent of respondents had smartphones, 53% with smartphones used apps in their clinical practice, and 96% of respondents who used apps would like to see more orthopaedic-related apps (Table 2). Respondents also answered questions regarding the types of apps they currently use in their clinical practice. The most common response, with 133 unique mentions (62%), was Epocrates. The next most popular apps included coding/billing apps (21 mentions), Medscape (13 mentions), Netter’s (10 mentions), and AAOS Now (seven mentions). When asked what type of apps respondents would be most interested in using, the top three rankings included textbook/reference, techniques/guides, and OITE/board review. Only 34 of the 401 respondents (8%) with smartphones were aware of the AAOS Now app, and of them, 19 (56%) had installed the app. Finally, respondents were asked how much they would be willing to pay for an app that saves 5 to 10 minutes per day or 30 minutes per week. The average prices were $24.70 and $43.98 for trainees (residents/fellows) and attending surgeons (all levels), respectively, and distribution ranges were calculated (Fig. 2). Forty respondents shared various comments before submitting the survey. The majority of comments emphasized the need for more/better orthopaedic-related apps, with specific requests for textbooks, references, board review materials, and billing/coding functions.

Fig. 1.

The distribution of smartphone platforms among respondents with a smartphone is shown.

Table 2.

Summary of survey responses

| Type of practitioner | Number of responses | Number with a smartphone | Number using apps | Desire for more apps | Price willing to pay? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resident | 319 | 273 (86%) | 162 (59%) | 156 (96%) | $24.93 |

| Fellow | 12 | 9 (75%) | 4 (44%) | 4 (100%) | $19.99 |

| Attending | |||||

| < 5 years | 24 | 21 (88%) | 10 (48%) | 10 (100%) | $14.72 |

| 5–15 years | 44 | 40 (91%) | 14 (35%) | 13 (93%) | $32.57 |

| > 15 years | 68 | 51 (75%) | 22 (43%) | 20 (91%) | $67.15 |

| Other | 9 | 7 (78%) | 2 (29%) | 2 (100%) | $30.20 |

| Total | 476 | 401 (84%) | 214 (53%) | 205 (96%) | $29.87 |

Fig. 2.

The price survey is shown for amounts that respondents are willing to pay for a useful smartphone app. The utility of the app was defined by saving 5 to 10 minutes per day or 30 minutes per week.

Discussion

During the last 5 years, smartphones and their associated apps have revolutionized the way we access information. Yet, despite the widespread prevalence of smartphones and apps available for general utilities, and specifically for physicians, few apps are designed for orthopaedic surgeons. This study is the first to summarize the apps currently available for orthopaedic caregivers and correlate those findings with the desires of orthopaedic residents and surgeons.

This study has some limitations. First, the reliance on using the online app stores for various smartphone platforms is not ideal. Because no independent or objective rating tools are available, the Apple and Android app stores that were required to collect information include subjective responses and are inherently moving targets. By the time of publication, the number of available apps, and their ratings and rankings, will change. For this reason, a comparison of results spaced 8 months apart was performed in an attempt to reduce the effect of changes with time. However, the purpose of this report is meant to highlight salient features regarding the prevalence of orthopaedic-related apps and their use, and these data can help guide surgeons and developers. Second, I relied on a voluntarily-distributed and nonvalidated brief survey of ACGME-accredited orthopaedic programs. The number of individuals who ultimately received the survey via email was not recorded and was likely influenced by the bias of the program director or coordinator who originally received the request. From this sample, the 476 unique responses may not be representative of the 20,000 orthopaedic surgeons in North America. Nevertheless, results of this survey are consistent with a published estimate of the prevalence of smartphones [7]. Third, the survey was conducted at ACGME-accredited programs resulting in a bias toward academic centers, trainees (residents/fellows), and younger surgeons. Despite the limitations of this “snapshot” survey technique, the use of smartphones and apps in clinical practice is only likely to increase, and the current perspective of residents and fellows or “early-adopters” may be more informative than nationally representative data in the context of future potential for smartphone utility in practice.

The findings from part one of the study are consistent with the rapid expansion of smartphone apps, and specifically iPhone apps. Consistent with general trends, smartphone platforms other than the iPhone trail far behind in offering apps for orthopaedic surgeons. However, even among the apps available in the iPhone app store, 72% had less than 10 votes each, suggesting a low number of downloads by users. Even AAOS Now and AO Surgery Reference, apps created by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and the AO Foundation, respectively, had relatively few ratings (ranked #10 and #15, respectively; Table 1).

The survey results (part two) revealed that 84% of orthopaedic students and caregivers currently use a smartphone, and that 53% of them use apps in their clinical practice. This was higher than the approximately 29% of adult cell phone users who reportedly use apps on their phone [13]. Regarding the distribution of smartphone operating systems in the United States, a report from July 2010 stated that the Blackberry, iPhone, and Android have 39%, 24%, and 17% of the market share, respectively [7]. Of the orthopaedic caregivers who use apps, a nearly unanimous 96% would like to see more apps available to orthopaedic surgeons and are willing to pay an average of nearly $30 for an app that saves 5 to 10 minutes a day or 30 minutes per week. This pricing is consistent with the average cost of $22.39 for paid apps. The most desired categories of apps by practitioners were textbook/reference, techniques/guides, OITE/board review, and billing/coding, which were different from the most prevalent types of available apps: technique guides, reference, and industry/news. An overwhelming number of respondents specifically mentioned Epocrates as their most useful app, a free drug reference tool, and Medscape, a drug and procedure reference, as their second most useful app [11, 16]. The fact that Epocrates and Medscape are clinical reference tools available elsewhere online emphasizes the fact that the utility of smartphone apps does not necessarily rest in novelty, but rather in accessibility and portability. Consistent with other results, these programs also are the top two ranked apps on a medical app ranking website run by physicians and medical students [10].

The idea of using smartphone apps in clinical practice is not without concern. Currently, there is no way to regulate the content or validity of information in published programs, a challenge faced by other forms of emerging technology [4, 15]. Rather, consumers either must independently verify the information provided or must trust the name of the app publisher. Because the visual display of phones is limited by size, computers are unlikely to be replaced by smartphones; however, custom apps designed for specific functions are a unique attribute and their prevalence and use in clinical practice are likely to increase.

The use of smartphone apps is prevalent among the orthopaedic residents, fellows, and attending surgeons surveyed, and most with smartphones use apps in their medical practice. However, there is a paucity of highly ranked apps available for orthopaedic caregivers, despite a strong need and desire. Data from this study may help orthopaedic surgeons identify more useful apps in their clinical practice and advise developers to create more relevant, useful, and high-quality apps.

Appendix 1.

Footnotes

The author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

References

- 1.Apple. iPhone App Store. 2010. Apple. Available at: http://www.apple.com/iphone/apps-for-iphone/#heroOverview. Accessed September 14, 2010.

- 2.Archbold HA, Guha AR, Shyamsundar S, McBride SJ, Charlwood P, Wray R. The use of multi-media messaging in the referral of musculoskeletal limb injuries to a tertiary trauma unit using: a 1-month evaluation. Injury. 2005;36:560–566. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beredjiklian PK, Bozentka DJ, Steinberg DR, Bernstein J. Evaluating the source and content of orthopaedic information on the Internet: the case of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:1540–1543. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200011000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyer C, Selby M, Scherrer JR, Appel RD. The Health On the Net Code of Conduct for medical and health Websites. Comput Biol Med. 1998;28:603–610. doi: 10.1016/S0010-4825(98)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burdette SD, Herchline TE, Oehler R. Surfing the web: practicing medicine in a technological age: using smartphones in clinical practice. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:117–122. doi: 10.1086/588788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chin KR, Adams SB, Jr, Khoury L, Zurakowski D. Patient behavior if given their surgeon’s cellular telephone number. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;439:260–268. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000180607.38604.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.comScore. July 2010 U.S. Mobile Subscriber Market Share. 2010. Available at: http://www.comscore.com/layout/set/popup/Press_Events/Press_Releases/2010/9/comScore_Reports_July_2010_U.S._Mobile_Subscriber_Market_Share. Accessed September 16, 2010.

- 8.Dala-Ali BM, Lloyd MA, Al-Abed Y. The uses of the iPhone for surgeons. Surgeon. 2011;9:44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elkaim M, Rogier A, Langlois J, Thevenin-Lemoine C, Abelin-Genevois K, Vialle R. Teleconsultation using multimedia messaging service for management plan in pediatric orthopaedics: a pilot study. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30:296–300. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181d35b10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.iMedicalApps. 2010. Available at: http://imedicalapps.com/. Accessed September 27, 2010.

- 11.Oehler RL, Smith K, Toney JF. Infectious diseases resources for the iPhone. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1268–1274. doi: 10.1086/651602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rozental TD, Lonner JH, Parekh SG. The Internet as a communication tool for academic orthopaedic surgery departments in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:987–991. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silverman D. Are you a member of the ‘Apps Culture’? San Francisco Chronicle. Sept 15, 2010.

- 14.Sprague S, Quigley L, Bhandari M. Survey design in orthopaedic surgery: getting surgeons to respond. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(suppl 3):27–34. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Starman JS, Gettys FK, Capo JA, Fleischli JE, Norton HJ, Karunakar MA. Quality and content of Internet-based information for ten common orthopaedic sports medicine diagnoses. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:1612–1618. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terry M. Medical apps for smartphones. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16:17–22. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2010.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]