Abstract

Background

Osteoporotic fractures are a major public health issue. The literature suggests there are variations in occurrence of fractures by ethnicity and race.

Questions/purposes

My purpose is to review current literature related to the influence of ethnicity and race on the (1) epidemiology of fracture; (2) prevalence of osteoporosis by bone mineral density; (3) consequences of osteoporotic hip fracture; (4) differences in risk fracture for fracture; and (5) disparities in screening, diagnosis, and treatment of osteoporosis.

Methods

Current literature was selectively reviewed related to osteoporosis, ethnicity, and race.

Results

Ethnicity and race, like sex, influence the epidemiology of fractures, with highest fracture rates in white women. Bone mineral density is higher in African Americans; however, these women are more likely to die after hip fracture, have longer hospital stays, and are less likely to be ambulatory at discharge. Consistent risk factors for fracture across ethnicity include older age, lower bone mineral density, previous history of fracture, and history of two or more falls. Ethnic and racial disparities exist in the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of osteoporosis.

Conclusions

Across ethnic and racial groups, more women experience fractures than the combined number of women who experience breast cancer, myocardial infarction, and coronary death in 1 year. Prevention efforts should target all women, irrespective of their race/ethnicity, especially if they have multiple risk factors.

Introduction

Osteoporotic fractures are a major public health problem. Such fractures result in serious morbidity, disability, quality of life, and mortality consequences. Understanding osteoporotic fractures is important for creating successful interventions to decrease such fractures and improve the delivery of health care.

Ethnicity and race are important factors influencing the incidence of osteoporosis. Furthermore, there are differences in risk factors and treatment outcomes for osteoporosis based on ethnicity and race. Understanding ethnic and racial influences on osteoporotic fractures is critical to decreasing the burden of such fractures on patients and society.

Given the current demographic trends leading to an increase in the number of persons older than 65 years, the numbers of fractures will increase even if fracture incidence rates remain stable. While a decline in hip fractures has occurred in white women [2], it has increased in Hispanic women [33]. Moreover, given the increase in life expectancy among African Americans and Hispanics, the number of fractures will increase in these groups. In 2005, 12% of all fractures occurred in nonwhites. By 2025, this percentage will rise to 21% [3]. Osteoporotic fractures are clearly a critical public health issue.

The purpose of this review is to address the following questions: (1) Does ethnicity and race influence the epidemiology of osteoporotic fracture? (2) Does the prevalence of osteoporosis by bone mineral density (BMD) vary by ethnicity and race? (3) Do the consequences of osteoporotic hip fracture differ by ethnicity and race? (4) Do risk factors for osteoporosis differ by ethnicity and race? (5) Are there disparities in screening, diagnosis, and treatment for osteoporosis among different ethnic and racial groups?

Search Strategy and Criteria

Selected articles related to osteoporosis, ethnicity, and race were reviewed for inclusion in the data analysis. Leading articles were referenced in the manuscript. A comprehensive literature search was not performed.

The Influence of Ethnicity and Race on the Epidemiology of Fractures

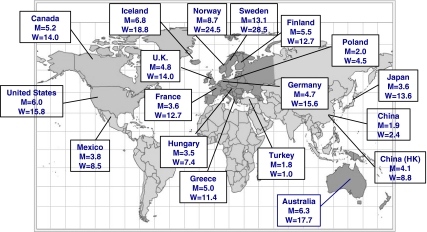

Worldwide, the frequency of hip fractures varies greatly by race and ethnicity [23] (Fig. 1). The lifetime risk of hip fracture at age 50 years in the United States is 15.8% and 6.0% in women and men, respectively, compared to 2.4% and 1.9% in Chinese women and men, respectively, and 8.5% and 3.8% in Hispanic women and men, respectively [12, 23, 27] (Fig. 1). Rates of hip fracture are highest in Northern European countries, where the 10-year relative probability of hip fractures, averaged for age and sex and adjusted to the probability of Sweden, is 1.24 in Norway compared to 0.62 in Singapore and 0.08 in Chile [23]. Some of this variability in hip fracture rates could reflect lack of representative populations in the various studies, as well as other methodology problems, but it is the only data available for some countries. For most countries in which data are available, osteoporotic hip fractures are an important public health issue.

Fig. 1.

Lifetime risk (%) of hip fracture at age 50 years in men (M) and women (W) is shown according to country [23]. The frequency of hip fractures varies greatly by race and ethnicity. Reproduced with permission and copyright 2002 of John Wiley & Sons, Inc, from Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C, Jonsson B, Oden A, Ogelsby AK. International variations in hip fracture probabilities: implications for risk assessment. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1237–1244. Morales-Torres J, Gutierrez-Urena S; Osteoporosis Committee of Pan-American League of Associations for Rheumatology. The burden of osteoporosis in Latin America. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:625–632.

There is much less ethnic and racial variability in morphometric vertebral fractures worldwide [5, 10, 12]. For example, the prevalence of vertebral fractures in women older than 65 years is 70% for white women, 68% for Japanese women, 55% for Mexican women, and 50% in African American women. This is surprising since both vertebral fracture and hip fractures are the hallmark of osteoporosis. Factors contributing to the lower geographic and racial variability in vertebral fractures are unknown.

Sex is a strong determinant of the risk of fracture depending on ethnicity and race. In general, white women experience hip fractures about twice more than men, especially in countries with high incidence rates, but the sex difference in hip fracture risk in African Americans and Asians is negligible. Rates of hip fracture are about 50% lower in African American and Asian women than in white women. Ethnic and race variability is much lower for men, although white men tend to have slightly higher hip fracture rates than Asian and African American men [12].

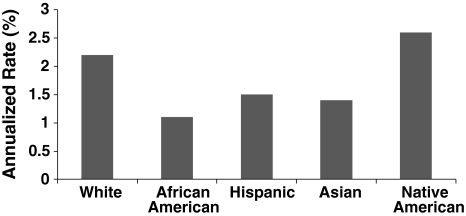

This interplay between sex and ethnicity/race is illustrated by the risk of fracture for women in the United States. Annual hip fracture rates in the United States are highest in white women (140.7 per 100,000), followed by Asian women (85.4 per 100,000), African American women (57.3 per 100,000), and Hispanic women (49.7 per 100,000) [29]. Similar ethnic and race variability in women is observed for all fractures [1, 7, 8], with annualized rates greater than 2% for white and Native American women and lower rates for African American, Hispanic, and Asian women (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

A graph shows annualized rates of fracture by race/ethnicity according to the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study [8]. The annualized rates are greater than 2% for white and Native American women and lower for African American, Hispanic, and Asian women. Reproduced with permission and copyright 2007 of John Wiley & Sons, Inc, from Cauley JA, Wu L, Wampler NS, Barnhart JM, Allison M, Chen Z, Jackson R, Robbins J. Clinical risk factors for fractures in multi-ethnic women: The Women’s Health Initiative. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1816–1826.

Ethnicity and race also influence where the fracture occurs. For example, among African American Medicare beneficiaries, the fracture rate ratio, compared to white patients, is 0.46 for hip fracture, 0.25 for spine fracture, 0.32 for distal radius, and 0.36 for humerus fractures [30]. Greater variability is observed for Hispanic women, with rate ratios ranging from 0.68 for hip fractures to 0.90 for distal radius fractures. This has important clinical implications in interpreting the World Health Organization (WHO) Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) probabilities in each ethnic group, since the FRAX calculators adjust for ethnic differences in hip fracture alone (http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX) [16].

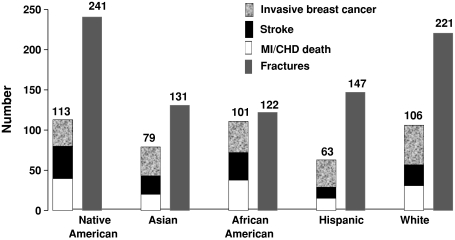

Despite the lower relative risk of fractures in minority women, their absolute risk of fracture is still substantial. Fractures are more common in minority women than the combined number of myocardial infarctions (MIs), coronary heart disease (CHD) deaths, and breast cancers [7] (Fig. 3). Using annualized incidence rates for all fractures, breast cancer, MI, and CHD deaths observed in the Observational Study of the Women’s Health Initiative, more African American, Asian, Hispanic, and Native American women experience a fracture in 1 year than the combined number of those who experience breast cancer and a composite CHD end point of MI/CHD deaths.

Fig. 3.

Fractures are more common in minority women than MI/CHD death, stroke, and breast cancer combined in 1 year [7]. Data are expressed as number of cases per year per 10,000 women. Reproduced with kind permission and copyright 2008 of Springer Science + Business Media BV from Cauley JA, Wampler NS, Barnhart JM, Wu L, Allison M, Chen Z, Hendrix S, Robbins J, Jackson RD; Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Incidence of fractures compared to cardiovascular disease and breast cancer: The Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:1717–1723. MI/CHD = myocardial infarction/coronary heart disease.

Prevalence of Osteoporosis by BMD and Ethnicity and Race

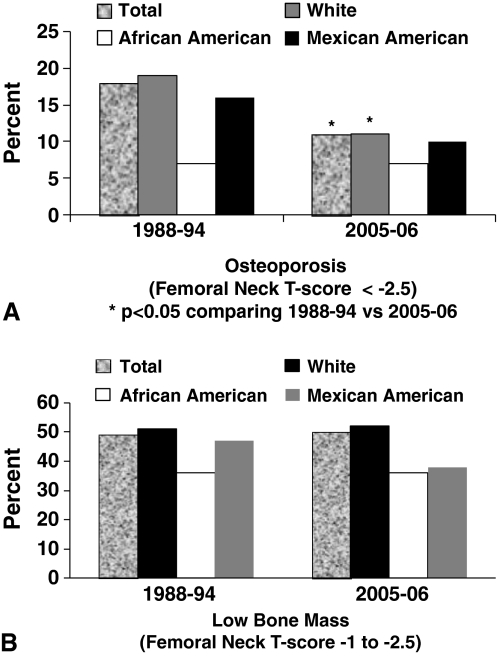

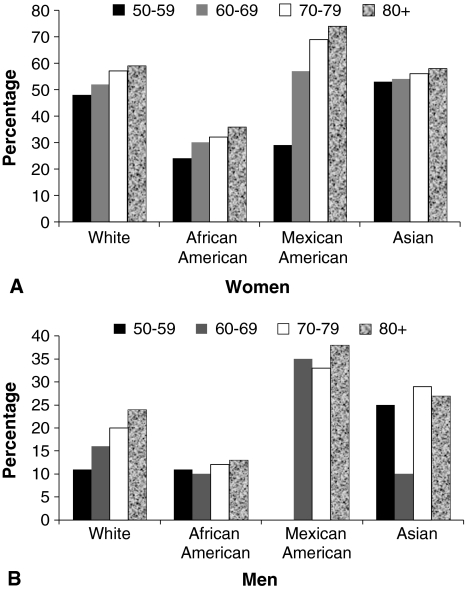

Ethnicity and race influence the prevalence of osteoporosis as defined by BMD. The WHO defines osteoporosis as a T score of less than −2.5 [28]. The overall prevalence of osteoporosis by BMD was about 18% in white women in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), 1988 to 1994, and declined to about 10% in NHANES 2005 to 2006 [24] (Fig. 4A). The prevalence is lower among African Americans (6%), but the prevalence for this group did not decline between the two NHANES studies. Among Hispanics, the prevalence was about 16% in 1988 to 1994 and declined to about 10% by 2005 to 2006, but this decline was not statistically significant for Hispanics. The decline in the prevalence of osteoporosis in all groups was independent of body mass index and bisphosphonate use. However, the prevalence of low bone mass (T score of −1 to < −2.5) did not change over time (Fig. 4B) and was about 50% in whites, compared to approximately 38% to 39% in Hispanics and African Americans, respectively. It is unclear why rates of osteoporosis declined for whites and Hispanics but not for African Americans.

Fig. 4A–B.

(A) The graph shows the prevalence of osteoporosis in NHANES III (1988–1994) and NHANES (2005–2006) for women regarding femoral neck BMD. The overall prevalence of osteoporosis by BMD was about 18% in white women from 1988 to 1994 and declined to about 10% from 2005 to 2006. (B) The graph shows the prevalence of low BMD in NHANES III (1988–1994) and NHANES (2005–2006) for women regarding femoral neck BMD [24]. The prevalence of low bone mass (T score of −1 to < −2.5) did not change over time. Reproduced with permission and copyright 2010 of John Wiley & Sons, Inc, from Looker AC, Melton LJ 3rd, Harris TB, Borrud LG, Shepherd JA. Prevalence and trends in low femur bone density among older US adults: NHANES 2005–2006 compared with NHANES III. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:64–71.

Consequences of Osteoporotic Hip Fractures: Do They Differ by Ethnicity and Race?

Both hip and vertebral fractures are associated with an increased risk of mortality [6], but mortality after hip fracture is higher among African American women than among white women [22]. The factors contributing to the higher mortality rate among African American women after a hip fracture are not completely understood but could reflect their older age at the time of fracture, greater comorbidity, or disparities in health care. Indeed, the average number of diagnoses at admission to the hospital at time of hip fracture is greater among African American women than white women [21].

Hip fractures have serious consequences regarding mobility and independent living. About 50% of women are unable to achieve their prefracture walking ability after their hip fracture [25]. Most of the research on the consequences of hip fracture has been carried out in white patients, but one small study suggests the percentage of patients with hip fracture who were nonambulatory at the time of their discharge was six times higher among African American women than among white women [21]. More data are clearly needed on the consequences of osteoporosis in nonwhites.

Do Risk Factors for Fracture Differ by Ethnicity and Race?

Risk factors for fracture include BMD, bone geometry, age, fall rates, fracture history, and medication use. Higher BMD is believed to protect against fracture. In population studies, BMD is consistently higher in African American women than in white women [1, 4, 24] at every level of body weight [19, 20] and could contribute to their lower fracture rates. However, differences in hip geometry could also contribute. Longer hip axis lengths have been linked to an increased risk of hip fracture [18], and hip axis lengths are reportedly shorter among African Americans and Asians, even after adjusting for height [11].

Differences are identified in the areal BMD between ethnic and racial groups and sex. Areal BMD integrates the size of the bone with its thickness and true volumetric density. While areal BMD is similar in white and Asian patients, Asians reportedly have higher trabecular volumetric BMD, at least in older men, which could contribute to their lower fracture rates [26]. Two small cross-sectional studies in Chinese women compared to white women show Chinese women have higher trabecular number and lower trabecular spacing [31, 32]. Chinese women also have higher cortical thickness and density. Thus, these studies suggest important mechanisms that contribute to lower fracture rates in Asians, despite their lower areal BMD. More data are clearly needed on ethnic differences in trabecular and cortical volumetric BMD and hip geometry.

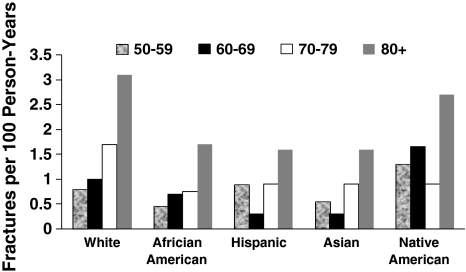

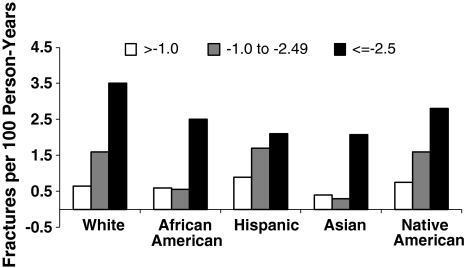

Fracture rates increase with age in all ethnic and racial groups [1, 8] (Fig. 5). Across all ethnicities, low BMD is a consistent risk factor for fractures [1] (Fig. 6). Most fractures occur because of a fall, but little is known about ethnic differences in fall rate. Fall rates were similar in African American and white patients, but the circumstances of falling appeared to differ [17]. African American women were more likely to fall on their hand or wrist, perhaps breaking the impact of their fall, resulting in a lower risk of hip fracture.

Fig. 5.

A graph shows fracture rates per 100 person-years by age among women of different ethnic origin [1]. The fracture rates increased with age in all ethnic and racial groups. Reproduced with permission and copyright 2005 of John Wiley & Sons, Inc, from Barrett-Connor E, Siris ES, Wehren LE, Miller PD, Abbott TA, Berger ML, Santora AC, Sherwood LM. Osteoporosis and fracture risk in women of different ethnic groups. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:185–194.

Fig. 6.

A graph shows fracture rates per 100 person-years by ethnicity and T-score according to the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment Study [1]. Across all ethnicities, low BMD is a consistent risk factor for fractures. Reproduced with permission and copyright 2005 of John Wiley & Sons, Inc, from Barrett-Connor E, Siris ES, Wehren LE, Miller PD, Abbott TA, Berger ML, Santora AC, Sherwood LM. Osteoporosis and fracture risk in women of different ethnic groups. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:185–194.

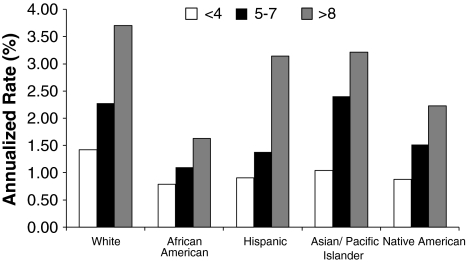

Many risk factors for fracture have been identified in white women; much less is known about risk factors for fracture in nonwhite women. In a prospective study of 159,579 women between 50 and 79 years of age [8], annualized rates of fracture were highest in whites (2%) and Native Americans (2%), followed by Hispanics (1.3%), Asians (1.2%), and African Americans (0.9%). Three risk factors common to all groups were older age, positive history of prior fracture, and positive history of two or more falls (Table 1). Some risk factors were related to specific ethnic or racial groups: for African Americans, at least a high school education; for Hispanics, height (> 162 cm), arthritis, corticosteroid use, and parental history of fracture; for Asians, current hormone therapy, parity (at least five); and for Native Americans, current hormone therapy. Women with eight or more risk factors had twice the rate of fracture compared to women with four or fewer risk factors (Fig. 7).

Table 1.

Multivariate models of fracture risk within ethnic groups

| Variable | Reference/unit | Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | African American | Hispanic | Asian | Native American | ||

| Nonmodifiable | ||||||

| Age (years) | Per 5 years | 1.10 (1.09, 1.12) | 0.98 (0.92, 1.05) | 1.13 (1.02, 1.26) | 1.15 (1.02, 1.29) | 1.02 (0.81, 1.28) |

| Years since menopause | 10–20 versus < 10 | 1.05 (1.01, 1.10) | 1.09 (0.90, 1.32) | 0.99 (0.76, 1.30) | 1.06 (0.76, 1.47) | 1.54 (0.75, 3.17) |

| ≥ 20 versus < 10 | 1.09 (1.03, 1.16) | 1.23 (0.98, 1.54) | 0.85 (0.60, 1.21) | 1.08 (0.70, 1.66) | 1.16 (0.50, 2.71) | |

| Education > high school | ≤ high school | 1.07 (1.02, 1.11) | 1.23 (1.01, 1.49) | 1.09 (.086, 1.38) | 1.11 (0.81, 1.53) | 1.69 (0.92, 3.12) |

| Education > college | ≤ high school | 1.10 (1.05, 1.14) | 1.23 (1.00, 1.51) | 1.22 (0.93, 1.58) | 1.28 (0.94, 1.74) | 1.62 (0.78, 3.37) |

| Living with partner | No | 0.90 (0.91, 0.97) | 1.00 (0.87, 1.16) | 0.99 (0.81, 1.22) | 1.01 (0.79, 1.29) | 1.28 (0.76, 2.16) |

| Parent fracture | No | 1.18 (1.15, 1.22) | 1.14 (0.96, 1.36) | 1.28 (1.04, 1.58) | 1.21 (0.96, 1.53) | 1.58 (0.94, 2.67) |

| Modifiable | ||||||

| Weight | > 70.5 kg | 0.95 (0.91, 0.98) | 0.93 (0.80, 1.09) | 0.91 (0.71, 1.18) | 0.81 (0.45, 1.47) | 1.02 (0.59, 1.76) |

| Height | > 162 cm | 1.14 (1.10, 1.18) | 1.01 (0.86, 1.18) | 1.56 (1.11, 2.17) | 1.46 (0.85, 2.52) | 1.03 (0.56, 1.89) |

| Daily caffeine intake | > 188 mg | 1.04 (1.00, 1.07) | 0.90 (0.72, 1.12) | 1.08 (0.83, 1.40) | 1.08 (0.80, 1.47) | 0.64 (0.35, 1.16) |

| Current smoking | No | 1.09 (1.02, 1.15) | 1.04 (0.83, 1.30) | 0.81 (0.52, 1.26) | 0.90 (0.48, 1.72) | 1.14 (0.54, 2.43) |

| Fracture bone since age 55 years | No | 1.55 (1.49, 1.61) | 1.74 (1.38, 2.20) | 1.86 (1.39, 2.50) | 1.50 (1.10, 2.05) | 2.89 (1.47, 5.66) |

| > 2 falls | ≤ 2 | 1.27 (1.22, 1.32) | 1.67 (1.38, 2.02) | 1.80 (1.40, 2.32) | 1.41 (1.04, 1.91) | 1.38 (0.75, 2.55) |

| Current hormone therapy (< 5 years) | None/past user | 0.86 (0.82, 0.91) | 0.99 (0.78, 1.25) | 0.99 (0.73, 1.33) | 0.74 (0.52, 1.06) | 0.55 (0.21, 1.43) |

| Current hormone therapy (≥ 5 years) | None/past user | 0.77 (0.75, 0.80) | 0.91 (0.75, 1.11) | 0.85 (0.66, 1.09) | 0.63 (0.48, 0.82) | 0.49 (0.26, 0.92) |

| Corticosteroid use (> 2 years) | No | 1.43 (1.22, 1.68) | 1.54 (0.82, 2.90) | 3.88 (1.89, 7.99) | 0.73 (0.10, 5.27) | 2.75 (0.26, 28.93) |

| Sedatives/antiolytics | No | 1.09 (1.02, 1.15) | 1.21 (0.92, 1.60) | 1.02 (0.67, 1.54) | 1.09 (0.56, 2.15) | 1.17 (0.50, 2.74) |

| History of arthritis | No | 1.13 (1.09, 1.16) | 1.07 (0.92, 1.25) | 1.29 (1.05, 1.59) | 1.08 (0.85, 1.37) | 1.39 (0.82, 2.34) |

| Depression | No | 1.11 (1.07, 1.15) | 1.04 (0.89, 1.22) | 1.12 (0.91, 1.38) | 1.14 (0.86, 1.52) | 1.54 (0.91, 2.61) |

| Health status | ||||||

| Excellent/very good/good | Fair/poor | 0.80 (0.76, 0.84) | 0.97 (0.80, 1.17) | 1.01 (0.77, 1.32) | 0.81 (0.56, 1.16) | 0.82 (0.44, 1.52) |

| Parity | ||||||

| 1 | None | 0.95 (0.88, 1.02) | 1.33 (0.95,1.86) | 1.08 (0.67, 1.73) | 1.77 (1.06, 2.96) | 0.54 (0.12, 2.40) |

| 2–4 | None | 0.94 (0.90, 0.99) | 1.10 (0.82, 1.46) | 0.85 (0.60, 1.20) | 1.25 (0.84, 1.87) | 1.09 (0.35, 3.42) |

| 5+ | None | 0.95 (0.90, 1.00) | 1.13 (0.84, 1.54) | 0.81 (0.56, 1.16) | 1.65 (1.06, 2.56) | 1.43 (0.44, 4.61) |

Reproduced with permission and copyright 2007 of John Wiley & Sons, Inc, from Cauley JA, Wu L, Wampler NS, Barnhart JM, Allison M, Chen Z, Jackson R, Robbins J. Clinical risk factors for fractures in multi-ethnic women: The Women’s Health Initiative. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1816-1826.

Fig. 7.

Graph shows annualized incidence rate of fracture by the total number of risk factors across ethnic group [8]. Women with eight or more risk factors had twice the rate of fracture compared to women with four or fewer risk factors. Reproduced with permission and copyright 2007 of John Wiley & Sons, Inc, from Cauley JA, Wu L, Wampler NS, Barnhart JM, Allison M, Chen Z, Jackson R, Robbins J. Clinical risk factors for fractures in multi-ethnic women: The Women’s Health Initiative. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1816–1826.

Ethnicity and race influenced the risk of fracture even after adjusting for multiple variables (Table 2). Overall, the risk of fracture was 49% lower among African American women than among white women. Among Hispanic and Asian women, there was little attenuation in the risk for fracture after adjusting for multiple risk factors. In the subgroup of women with BMD, the lower risk of fracture among African American and Hispanic women was independent of BMD. However, there was some attenuation in ethnic differences in models with total hip BMD.

Table 2.

Multivariate models for fracture within each ethnic group*

| Model | Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| African American | Hispanic | Asian/Pacific Islander | Native American | |

| Total population (n = 159,579) | ||||

| Age adjusted | 0.51 | 0.64 | 0.59 | 1.03 |

| (0.48, 0.54) | (0.59, 0.70) | (0.53, 0.65) | (0.85, 1.25) | |

| MV adjusted† | 0.51 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.95 |

| (0.47, 0.55) | (0.60, 0.74) | (0.59, 0.74) | (0.75, 1.20) | |

| BMD cohort (n = 12,705) | ||||

| Age adjusted | 0.51 | 0.64 | ||

| (0.48, 0.54) | (0.59, 0.70) | |||

| MV adjusted† | 0.51 | 0.67 | ||

| (0.47, 0.55) | (0.60, 0.74) | |||

| MV + total hip BMD | 0.65 | 0.75 | ||

| (0.53, 0.80) | (0.57, 0.99) | |||

| MV + lumbar spine BMD | 0.56 | 0.73 | ||

| (0.45, 0.69) | (0.56, 0.97) | |||

* White women form the referent group [8]; †multivariate models: adjusted for age, years since menopause, education, living with a partner, height, weight, caffeine intake, smoking, fracture history, parental fracture history, falls, current hormone therapy use (> 5 years), corticosteroid use (> 2 years), sedative/anxiolytics use, arthritis, depression, health status, and parity; MV = multivariate; BMD = bone mineral density. Reproduced with permission and copyright 2007 of John Wiley & Sons, Inc, from Cauley JA, Wu L, Wampler NS, Barnhart JM, Allison M, Chen Z, Jackson R, Robbins J. Clinical risk factors for fractures in multi-ethnic women: The Women’s Health Initiative. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1816-1826.

Less is known about whether rates of bone loss vary by ethnicity. Rates of bone loss during menopause were similar across ethnicities [19]. Among a group of women aged 67 years and older, rates of areal bone loss were lower among African American women than among white women [4], although the increase in the rate with advancing age was greater among the African American women.

Are There Disparities in Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Osteoporosis Between Ethnic and Racial Groups?

Use of BMD to screen for osteoporosis differs based on ethnicity and race. Among Medicare enrollees, 33% of white women have screenings for BMD, but only 5% of African American women have such screenings [13]. Diagnosis of osteoporosis also varies by ethnicity and race. Using Medicare fracture claims data, the proportion of African American women who, despite their fracture, are diagnosed with osteoporosis is less than 40%, even at age 80 years or older [9] (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8A–B.

Graphs show (A) female and (B) male Medicare beneficiaries with fracture claims (hip, distal forearm, or spine) and the proportion with osteoporosis diagnosis by age [9]. The proportion of African American women who, despite their fracture, are diagnosed with osteoporosis is less than 40%, even after age 80 years. Reproduced with kind permission and copyright 2009 of Springer Science + Business Media BV from Cheng H, Gary LC, Curtis JR, Saag KG, Kilgore ML, Morrisey MA, Matthews R, Smith W, Yun H, Delzell E. Estimated prevalence and patterns of presumed osteoporosis among older Americans based on Medicare data. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1507–1515.

New treatment guidelines from the National Osteoporosis Foundation suggest more than 40% of African American women and more than 60% of Hispanic women older than 80 years meet the guidelines for treatment [15], yet treatment disparities are evident. New treatment guidelines suggest women with a 10-year probability of hip fracture of 3% or greater should be recommended for therapy. However, roughly 20% of white women and less than 12% of African American women who meet this guideline receive treatment. At every level of predicted hip fracture risk, the percentage of women receiving osteoporosis therapies is lower among African American women [14].

Discussion

Osteoporosis-related fractures remain a serious public health issue. The lifetime risk of hip fracture at age 50 years in the United States is 15.8% and 6.0% in women and men, respectively, and results in serious morbidity and mortality for patients [12, 23, 27]. Identification of individuals at risk of fracture is important to effectively target healthcare interventions. Multiple factors influence the risk of fracture. This review highlighted the influence of ethnicity and race on osteoporosis and fragility fracture and specifically addressed the following questions: (1) Do ethnicity and race influence the epidemiology of osteoporotic fracture? (2) Does the prevalence of osteoporosis by BMD vary by ethnicity and race? (3) Do the consequences of osteoporotic hip fracture differ by ethnicity and race? (4) Do risk factors for osteoporosis differ by ethnicity and race? (5) Are there disparities in screening, diagnosis, and treatment for osteoporosis among different ethnic and racial groups?

Readers should be aware of the limitations of this review. First, the review was selective, not systematic, and any number of relevant papers could have been overlooked. Nonetheless, those reviewed persuasively document differences in each of the five areas explored. Second, the various articles used a variety of methods to obtain data and there are likely differences in the validity of the databases. These studies nonetheless report similar trends.

Ethnicity and race influence the epidemiology of fracture, as does sex. White women experience hip fractures about twice more than men, especially in countries with high incidence rates, but the sex difference in hip fracture risk in African Americans and Asians is negligible. Hip fracture rates in women are highest in whites, followed by Hispanics, Asians, and African Americans. Ethnic and race variability is much lower for men, although white men tend to have slightly higher hip fracture rates than Asian and African American men.

While these numbers suggest intervention strategies should emphasize whites and possibly Hispanics and Asians, the absolute risk of fracture in minority women is still substantial and is more common than the combined number of MIs, CHD deaths, and breast cancers [7]. The need to improve bone health is critical for all ethnic and racial groups, as well as both sexes.

The prevalence of osteoporosis is influenced by ethnicity and race. African Americans have both lower rates of osteoporosis and higher bone mass. However, the consequences of fracture are not lower in this ethnic group. Mortality after hip fracture is higher among African American women than among white women [22]. The factors contributing to this higher mortality rate are not completely understood but could reflect older age at the time of hip fracture, greater comorbidity, or disparities in health care. More research is needed to better understand this higher mortality and develop effective treatment strategies for this particular patient population.

Risk factors for fracture are influenced by ethnicity and race. Across all ethnicities, low BMD is a consistent risk factor for fractures [1]. However, the biologic factors influencing risk of fracture are more varied than BMD and include bone geometry and longer hip axis length. A reflection of this complexity of bone fragility is the fact that fracture history remains the strongest predictor of future fracture across all ethnic and racial groups in women. To emphasize that BMD is just one factor in the complex assessment of fracture risk assessment, lower risk of fracture among African American and Hispanic women is independent of BMD after adjusting for multiple risk factors. Ethnic and racial differences related to falls, education level, medication use, parity, and hormone replacement therapy influence fracture rate for specific groups. More sophisticated tools, which include the influence of ethnicity and race, must be developed to aid the clinician in assessing an individual patient’s risk of fracture.

There are substantial ethnic and racial healthcare disparities in screening for and treatment of osteoporosis. Despite the fact that the Bone Mass Measurement Act approved BMD screening for Medicare enrollees, the percentage of women who have had a dual-energy xray absorptiometry (DXA) scan is low: 33% among white women and only 5% among African American women [13]. While some progress has been made over the last two decades in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis, the proportion of women who have had a BMD measurement is only 30% in white women and 15% in African American women [13]. At every level of predicted hip fracture risk, the percentage of women receiving osteoporosis therapies is lower among African American women [14].

In summary, there is large ethnic and racial variability in hip and all fracture rates. Disparities exist among racial and ethnic groups in osteoporosis diagnosis, DXA measurement, and treatment. Across all ethnic and racial groups, more women experience fractures than the combined number of women who experience breast cancer, MI, and CHD death in 1 year. Prevention efforts should target all women, irrespective of their race and ethnicity, especially if they have multiple risk factors. Use of the FRAX tool may help identify women of all ethnicities who are at risk of fracture.

Footnotes

The author certifies that she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

References

- 1.Barrett-Connor E, Siris ES, Wehren LE, Miller PD, Abbott TA, Berger ML, Santora AC, Sherwood LM. Osteoporosis and fracture risk in women of different ethnic groups. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:185–194. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brauer CA, Coca-Perraillon M, Cutler DM, Rosen AB. Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA. 2009;302:1573–1579. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:465–475. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cauley JA, Lui LY, Stone KL, Hillier TA, Zmuda JM, Hochberg M, Beck TJ, Ensrud KE. Longitudinal study of changes in hip bone mineral density in Caucasian and African-American women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:183–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cauley JA, Palermo L, Vogt M, Ensrud KE, Ewing S, Hochberg M, Nevitt MC, Black DM. Prevalent vertebral fractures in black women and white women. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1458–1467. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Ensrud KC, Scott JC, Black D. Risk of mortality following clinical fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:556–561. doi: 10.1007/s001980070075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cauley JA, Wampler NS, Barnhart JM, Wu L, Allison M, Chen Z, Hendrix S, Robbins J. Jackson RD; Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Incidence of fractures compared to cardiovascular disease and breast cancer: The Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:1717–1723. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0634-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cauley JA, Wu L, Wampler NS, Barnhart JM, Allison M, Chen Z, Jackson R, Robbins J. Clinical risk factors for fractures in multi-ethnic women: The Women’s Health Initiative. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1816–1826. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng H, Gary LC, Curtis JR, Saag KG, Kilgore ML, Morrisey MA, Matthews R, Smith W, Yun H, Delzell E. Estimated prevalence and patterns of presumed osteoporosis among older Americans based on Medicare data. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1507–1515. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0835-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark P, Cons-Molina F, Deleze M, Ragi S, Haddock L, Zanchetta JR, Jaller JJ, Palermo L, Talavera JO, Messina DO, Morales-Torres J, Salmeron J, Navarrete A, Suarez E, Perez CM, Cummings SR. The prevalence of radiographic vertebral fractures in Latin American countries: the Latin American Vertebral Osteoporosis Study (LAVOS) Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:275–282. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0657-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cummings SR, Cauley JA, Palermo L, Ross PD, Wasnich RD, Black D, Faulkner KG. Racial differences in hip axis lengths might explain racial differences in rates of hip fracture: study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Osteoporos Int. 1994;4:226–229. doi: 10.1007/BF01623243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cummings SR, Melton LJ. Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet. 2002;359:1761–1767. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08657-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtis JR, Carbone L, Cheng H, Hayes B, Laster A, Matthews R, Saag KG, Sepanski R, Tanner SB, Delzell E. Longitudinal trends in use of bone mass measurement among older Americans, 1999–2005. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1061–1067. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curtis JR, McClure LA, Delzell E, Howard VJ, Orwoll E, Saag KG, Safford M, Howard G. Population-based fracture risk assessment and osteoporosis treatment disparities by race and gender. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:956–962. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1031-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dawson-Hughes B, Looker AC, Tosteson AN, Johansson H, Kanis JA, Melton LJ., 3rd The potential impact of new National Osteoporosis Foundation guidance on treatment patterns. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:41–52. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ettinger B, Black DM, Dawson-Hughes B, Pressman AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Updated fracture incidence rates for the US version of FRAX. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:25–33. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1032-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faulkner KA, Cauley JA, Zmuda JM, Landsittel DP, Nevitt MC, Newman AB, Studenski SA, Redfern MS. Ethnic differences in the frequency and circumstances of falling in older community-dwelling women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1774–1779. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faulkner KG, Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Pressman A, Jergas M, Genant HK. Hip axis length and osteoporotic fractures: study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10:506–508. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650100323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finkelstein JS, Brockwell SE, Mehta V, Greendale GA, Sowers MR, Ettinger B, Lo JC, Johnston JM, Cauley JA, Danielson ME, Neer RM. Bone mineral density changes during the menopause transition in a multiethnic cohort of women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:861–868. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finkelstein JS, Sowers M, Greendale GA, Lee ML, Neer RM, Cauley JA, Ettinger B. Ethnic variation in bone turnover in pre- and early perimenopausal women: effects of anthropometric and lifestyle factors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:3051–3056. doi: 10.1210/jc.87.7.3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furstenberg AL, Mezey MD. Differences in outcome between black and white elderly hip fracture patients. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:931–938. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobsen SJ, Goldberg J, Miles TP, Brody JA, Stiers W, Rimm AA. Race and sex differences in mortality following fracture of the hip. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:1147–1150. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.82.8.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Laet C, Jonsson B, Oden A, Ogelsby AK. International variations in hip fracture probabilities: implications for risk assessment. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1237–1244. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.7.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Looker AC, Melton LJ, 3rd, Harris TB, Borrud LG, Shepherd JA. Prevalence and trends in low femur bone density among older US adults: NHANES 2005–2006 compared with NHANES III. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:64–71. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magaziner J, Simonsick EM, Kashner TM, Hebel JR, Kenzora JE. Predictors of functional recovery one year following hospital discharge for hip fracture: a prospective study. J Gerontol. 1990;45:M101–M107. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.3.m101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marshall LM, Zmuda JM, Chan BK, Barrett-Connor E, Cauley JA, Ensrud KE, Lang TF. Orwoll ES; Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Research Group. Race and ethnic variation in proximal femur structure and BMD among older men. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:121–130. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morales-Torres J. Gutierrez-Urena S; Osteoporosis Committee of Pan-American League of Associations for Rheumatology. The burden of osteoporosis in Latin America. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:625–632. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1596-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention Diagnosis, and Therapy. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA. 2001;285:785–795. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.6.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silverman SL, Madison RE. Decreased incidence of hip fracture in Hispanics, Asians, and blacks: California Hospital Discharge Data. Am J Public Health. 1988;78:1482–1483. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.78.11.1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor AJ, Gary LC, Arora T, Becker DJ, Curtis JR, Kilgore ML, Morrisey MA, Saag KG, Matthews R, Yun H, Smith W, Delzell E. Clinical and demographic factors associated with fractures among older Americans. Osteoporos Int. 2010 June 18 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Walker MD, McMahon DJ, Udesky J, Liu G, Bilezikian JP. Application of high-resolution skeletal imaging to measurements of volumetric BMD and skeletal microarchitecture in Chinese-American and white women: explanation of a paradox. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:1953–1959. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang XF, Wang Q, Ghasem-Zadeh A, Evans A, McLeod C, Iuliano-Burns S, Seeman E. Differences in macro- and microarchitecture of the appendicular skeleton in young Chinese and white women. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:1946–1952. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zingmond DS, Melton LJ, 3rd, Silverman SL. Increasing hip fracture incidence in California Hispanics, 1983 to 2000. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:603–610. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1592-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]