Abstract

Objective

To describe the neonatal characteristics and outcomes of infants born during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic.

Study Design

A prospective cohort of pregnant women with ILI was enrolled between the months of June, 2009 and March, 2010. Neonatal characteristics, complication and outcomes were recorded.

Results

45 women were included; birth outcomes were available in 41 cases. 16 women had 2009 H1N1 infection and the remaining 25 that tested negative were included in the ILI group. Live births were similar in both groups. Average gestational age at delivery was over 39 weeks; with similar Apgar scores and cord gas pH values. Birth weights in the 2009 H1N1 group were on average 285 grams lower, 3186 vs. 3471 grams (p = 0.04). Three infants were admitted to the NICU.

Conclusions

In this cohort, 2009 H1N1 infection during pregnancy was associated with a lower birth weight when compared with ILI in pregnancy.

Keywords: HIN1, influenza in pregnancy, neonatal outcomes

Introduction

During the spring and summer of 2009, a novel influenza virus of swine origin was identified as 2009 H1N1 influenza. Mutations in the virus made human to human transmission possible, leading to a rapid increase in the number of cases and to a pandemic that quickly spread throughout the world. This prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to raise the pandemic alert to the highest level possible during an influenza outbreak, phase 6 1. Media coverage and public awareness made the influenza pandemic one of the most monitored public health events in recent history.

Historically, pregnant women have been at increased risk for complications during influenza outbreaks 2–4. Influenza vaccination guidelines developed by the federal government have generally placed pregnant women in the top-priority group 5. Changes in cardiovascular, pulmonary, hormonal and immunological systems; corresponding to normal maternal adaptation to pregnancy, have been implicated as the cause of the high morbidity and mortality observed 6. For this reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) started implementing direct surveillance of suspected cases of 2009 H1N1, requiring states to report probable and confirmed cases via a five-page standardized report form, with a one-page addendum added on May 4th, 2009 if the cases involved pregnant women 7.

Pregnancy during the 2009 H1N1 outbreak was identified as a major risk factor for severe disease, a tendency seen in previous pandemics. During the epidemic, pregnant women were four times more likely to be admitted to the hospital 7, had a 13-fold greater chance of admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) 8 and saw hospitalization rates of 55.3 per 100,000 compared to 7.7 per 100,000 in non-pregnant women 9. Of the 239 reproductive-aged women in California that were hospitalized or died from H1N1, 102 were pregnant or postpartum 10. Preterm delivery rates were reported as high as 30.2 % in affected women, significantly higher than the national average of 12.7% 11, 12. During the first months of the pandemic, only 0.62% of the cases were composed of pregnant women, yet they accounted for 13% of the entire mortality rate 7.

Although various investigations have reported an increase in adverse outcomes in pregnant women complicated with infection by influenza, the consequences on fetuses and newborns have not been thoroughly studied. The possibility of vertical transmission of the virus with direct fetal effect remains unknown. During seasonal influenza outbreaks, cord blood samples from newborns of infected mothers have failed to show the presence of the influenza virus or transplacental crossing of auto-antibodies formed during the infection 13. Concern has been raised with more virulent strands of the virus; viral genome has been detected in placental trophoblasts of women affected by the avian influenza A (H5N1) 14. A paucity of data exists concerning indirect effects on the fetus from the viral infection of the mother. Case reports in the past have reported an increase in congenital abnormalities in fetuses of mother infected by the influenza virus 15. High fevers experienced by the mother have been proposed as the initiating mechanism explaining the increase in cleft lip and palate, cardiovascular and neural tube defects seen in this group 15. Infection by strains of higher virulence could theoretically result in an increased incidence in fetal losses. During the influenza pandemic of 1918, which had one of the highest overall mortality rates reported during an influenza outbreak, reported a fetal loss rate as high as 50% 4. In the present study we evaluated the possible effects of maternal 2009 H1N1 infection compared to other causes of ILI on newborns.

Materials and Methods

A prospective cohort study was designed and performed to investigate fetal and neonatal outcomes of maternal influenza-like illness. During June of 2009 through March of 2010, pregnant women that seen in the triage unit of Women and Infants’ Hospital of Rhode Island with clinical characteristics of an influenza-like illness (ILI) were approached and invited to participate. This hospital is a large tertiary care unit that serves as a referral center for all of New England. ILI was defined as per the CDC as a fever over 100 °F and a cough and/or sore throat in the absence of other known causes of illness. During this outbreak, our hospital developed a treatment algorithm for pregnant women designed to provide direction and allow for a uniform management scheme. Women were also eligible for enrollment if the health care provider considered the patient to be at risk for the H1N1 infection based on clinical symptoms compatible with influenza even if the clinical course lacked the presence of fever. Rhode Island was one of 40 states that had been certified by the CDC to conduct their own testing on respiratory specimens with a real-time reverse-transcriptase (RT) PCR assay confirming the diagnosis of H1N1. This confirmatory test uses RT-PCR to isolate and amplify 2009 H1N1 viral RNA from nasopharyngeal swabs, which are then detected as a fluorescent signal by the Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast DX Realtime PCR instrument. This test was approved for emergency use by the FDA under the “emergency use authorization” (EUA) directive. The Department of Health of the State of Rhode Island conducted the confirmatory test on all pregnant women regardless of their hospitalization status. Women participating in another influenza study, immunocompromised, testing positive for group A streptococcal infection, with evidence of active tuberculosis or acute pyelonephritis were excluded from enrollment.

The institutional Review Board of the Women and Infants’ Hospital approved the study protocol. All participants signed informed, written consent. Research personnel interviewed the study subjects and collected data from their medical records. Maternal characteristics and outcomes of this cohort are the focus of a separate report. Neonatal characteristics and birth outcomes were collected. Delivery mode and indications for induction were elicited. Gestational age and weight at birth were recorded for all participants, along with Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes. The development of any maternal complications during delivery was also noted. The presence of neonatal complications such as intrauterine growth restriction or fetal anomalies was extracted from the available records. Admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and length of stay along with the need for respiratory support were collected. Information on development of neonatal complications such as seizures, sepsis, broncopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), persistent patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), necrotizing enterocolitis and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) were recorded. The presence of central nervous system complications like interventricular hemorrhage and periventricular leukomalacia were documented. Infants were tested for all influenza viruses and their results were cataloged. Final results on virology from maternal swabs conducted by the Department of Health of the state of Rhode Island were collected.

Categorical and continuous variables from both groups were compared and analyzed. The Statistical analysis software SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was utilized for this purpose. Means, medians, ranges, and proportions were calculated. Categorical variables were compared by Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were compared between groups using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and student t-test, depending on pattern of distribution. Multiple linear or logistic regressions were used to adjust for potential confounders. Two-tailed p-values are presented, with a value of p<0.05 considered to be statistically significant.

Results

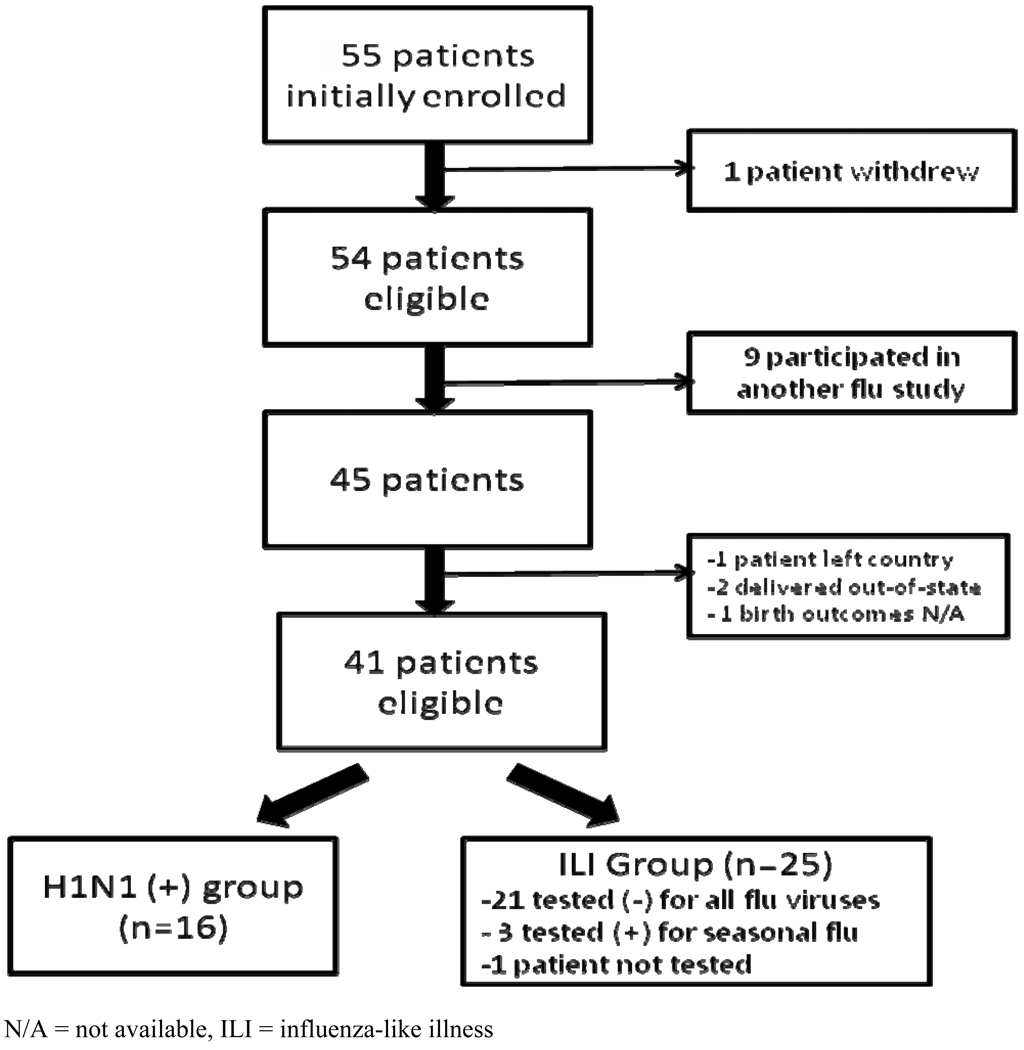

During June of 2009 through March of 2010, fifty four women met inclusion criteria and agreed to participate. Birth outcomes were available for fifty (90.9%) of the participants. Nine subjects were excluded due to their enrollment in another influenza study. Of the remaining 45, birth outcomes were available for forty one participants and are reported here. Sixteen of the forty one (39%) participants tested positive for H1N1 infection, as confirmed by RT-PCR done by the Department of Public Health for the State of Rhode Island. Twenty one women (52.5%) tested negative for any influenza virus, three (7.5%) tested positive for seasonal influenza viruses and one participant was not tested. All twenty five women not testing positive for H1N1 were grouped into an ILI group (Figure 1). The demographic characteristics of both groups of mothers were similar. The majority of the women in this cohort were treated in an outpatient setting, with only 27% of the patients hospitalized. A total of 39 out of the 41 enrolled received adequate antiviral therapy; all women in the 2009 H1N1 group received therapy compared to 92.8% of women in ILI group. No maternal deaths or admission to ICU were recorded in either cohort.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart

N/A = not available, ILI = influenza-like illness

All women included in our prospective review had a live birth, with the exception of one miscarriage diagnosed in the H1N1 (+) group (p = 0.4). No intrauterine demise or neonatal deaths were reported in either group. Characteristics of live birth outcomes are reported in table 1. Women with a proven H1N1 infection were not more likely to have a newborn with low one minute (p = 0.8) or five minute Apgar scores (p = 0.9). Cord gases at birth were obtained in 16% of the infants in the ILI group and in 21.4% of newborns in the H1N1 group. No differences were noted in cord pH (p = 0.9) and in cord base excess (p = 0.9).

Table 1.

Birth outcomes reported by influenza status

| Median (Range) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | H1N1 positive (n=15) | ILI (n=25) | p-value |

| Apgar – 1 minute | 8 (6–9) | 8 (4–9) | 0.8 |

| Apgar – 5 minute | 9 (8–9) | 9 (7–9) | 0.9 |

| Cord gas pH | 7.3 (7.3–7.4); n=3 | 7.3 (7.2–7.4); n=4 | 0.9 |

| Cord gas base excess | −1.7 (−5.8 – −0.8); n=3 | −1.2 (−8.4 – 5.0); n=4 | 0.9 |

| Mean (SD) | |||

| Gestational age at delivery (wks) (*) | 39.2 (1.6) | 39.6 (1.2) | 0.4 |

| Birth weight (g) (*) | 3186 (413) | 3471 (406) | 0.04 |

| Maximum temperature in labor (F) (*) | 98.8 (0.5) | 98.8 (0.6) | 0.9 |

Birth outcomes compared between both groups. (*) Normally distributed variables are reported as means and compared using the student t-test. The remaining variables are compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum. A p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. ILI = Influenza-like illness, SD = standard deviation, wks = weeks, g= grams, °F= Fahrenheit. ILI = Influenza-like.

Normally distributed continuous variables are reported in table 1. The average gestational ages at delivery in both groups were similar (39.2 vs. 39.6). One preterm delivery (< 37 weeks) was recorded in each of the groups. Mean birth weight for infants born to 2009 H1N1 positive mothers were 3186 grams, 285 grams less than the average 3471 grams recorded at birth on infants of women diagnosed with ILI (p = 0.04). Maternal maximum temperature during labor was found to be similar between both groups.

Table 2 shows all the characteristics and all the recorded complications noted during the delivery. Labor was induced in 33.3% of mothers that tested positive for 2009 H1N1 and in 32% of mothers cataloged as other causes of ILI. The most common reason for induction in both groups was for post term. The most common mode of delivery was spontaneous vaginal delivery for both the 2009 H1N1 positive group and the ILI group. Delivery via cesarean section was more common in women diagnosed with other causes of ILI (7/25, 28%) compared to the women infected with 2009 H1N1 (1/15, 6.6%). Premature rupture of membranes was diagnosed in three pregnancies complicated by 2009 H1N1 infection, one of which delivered preterm at 35 weeks. The time lapse from influenza infection to the development of premature rupture of membranes ranged from 7 to 29 weeks. Two pregnancies in each group were diagnosed with preeclampsia antenatally, one pregnancy in the 2009 H1N1 group developed preeclampsia postpartum. One fetus in the ILI group was macrosomic.

Table 2.

Characteristics and complications of delivery reported by influenza status

| N (Column %) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | H1N1 positive (n=14) | ILI (n=25) | p-value |

| Labor induction | 5 (33.3) | 8 (32.0) | 1.0 |

| Reason for induction | |||

| Postdates | 2 (40.0) | 3 (37.5) | 1.0 |

| Diabetes | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 1.0 |

| Preeclampsia | 1 (20.0) | 2 (25.0) | 1.0 |

| Chronic hypertension | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 1.0 |

| Thromboembolic disease | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 1.0 |

| Undocumented reason | 2 (40.0) | 0 | 1.0 |

| Delivery method | |||

| Vaginal – unassisted | 14 (93.3) | 17 (68.0) | 0.3 |

| Vaginal – assisted | 0 | 1 (4.0) | |

| C-section – elective | 1 (6.7) | 3 (12.0) | |

| C-section – unplanned | 0 | 4 (16.0) | |

| Premature rupture of membranes | 3 (20) | 0 | 0.1 |

| Preeclampsia (antepartum) | 2 (14.3) | 2 (8.0) | 0.6 |

| Postpartum Preeclampsia | 1 | 0 | |

| Other delivery complication | 2 (14.3) | 2 (8.0) | 0.6 |

| AVM & polyhydramnios | 0 | 1 | |

| GHTN | 1 | 0 | |

| Macrosomia | 0 | 1 | |

Delivery complications compared between both groups compared by Fisher’s exact test, a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. ILI= Influenza-like illness, C-section=cesarean section, AVM=Arterio-venous malformation, GHTN= Gestational hypertension.

Linear regression analysis controlling for maternal age, gestational age at delivery, ethnicity, maternal weight gain during pregnancy, educational status and insurance status was performed. After these possible confounders were examined, the relationship between infection status and decreased birth weight persisted (Table 3), although the association is weak given the small sample size.

Table 3.

Association of flu status and birth weight, adjusted for potential confounders (n=40)

| Regression model | Mean Difference in Birth weight for ILI vs. H1N1 (+) in grams (95% CI) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | 285 (12 – 557) | 0.04 |

| Adjusted for weight gain (lbs) (n=23) | 181 (−155 – 517) | 0.3 |

| Adjusted for GA (in wks) | 255 (−21 – 532) | 0.07 |

| Adjusted for age (years) | 265 (−3 – 533) | 0.05 |

| Adjusted for Hispanic ethnicity vs. non-Hispanic | 257 (−22 – 535) | 0.07 |

| Adjusted for education (< HS, HS, >HS) | 287 (12 – 563) | 0.04 |

| Adjusted for insurance (Medicaid/none vs. private/other) | 256 (−24 – 537) | 0.07 |

The overall maternal weight gain was not different between both groups. The mean maternal weight gain for women (+) for H1N1 was 29.5 lbs (range 2–60.5 lbs) compared to 31.1 (range 0.2–55.5) p = 0.8.

Infant complications were similar in both groups. The diagnosis of a fetal anomaly was a rare occurrence, with only one infant with a ventricular septal defect born to a woman with 2009 H1N1 infection that was diagnosed at 17 weeks gestation. The infant was delivered at 40 weeks gestational age and admitted to the NICU for 8 days for respiratory support. Despite its increased virulence, admissions to NICU were not more common in pregnancies affected by 2009 H1N1 infection. A total of 3 infants required admission, 2 were born to mother with ILI and one was born to an H1N1 positive mother. Table 4 shows the clinical characteristics of these patients. Infants admitted to NICU ranged in gestational age from 36.7 to 40 weeks. Length of stay in the NICU ranged from less than 24 hours to 8 days. Two of the infants developed respiratory distress and required supplemental oxygen while in the NICU. None of the newborns admitted to the intensive care unit required intubation or the use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) support. No major complications were reported in any of the three infants and all were discharged home with their mothers.

Table.

Characteristics of Infants admitted to NICU

| GA at delivery (wks) |

Infant birth weight (grams) |

Maternal H1N1 (+) PCR |

Apgar 1 min/ 5 min |

Length of stay (days) |

Supplemental Oxygen |

Ventilator support |

Sepsis | Seizure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case number 1 | 40 | 3230 | Yes | 8/9 | 8 | Yes | No | No | No |

| Case number 2 | 36.7 | 3668 | No | 6/7 | 1 | No | No | No | No |

| Case number 3 | 37.1 | 3930 | No | 4/8 | 2 | No | No | No | No |

Case #1 was born to a H1N1 + mother, Case #2 and #3 were born to mothers testing negative to all influenza viruses. GA= gestational age, wks= weeks, PCR= polymerase chain reaction.

Discussion

This study summarizes the neonatal outcomes of a cohort of pregnant women affected with influenza-like symptoms during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Various reports detailed the detrimental consequences the 2009 H1N1 infection can have on pregnant women, but a limited number of studies have focused on the effects of the infection on the neonate. The 2009 H1N1 swine influenza pandemic showed very different epidemiological characteristics compared to seasonal flu; the spike in the number of cases during spring and summer as opposed to winter along with the high virulence seen with this infection, provide a very different insight into the pathophysiology of pandemic influenza infection in pregnancy. We grouped all women that had influenza-like symptoms but tested negative for 2009 H1N1 and compared them to women with a proven 2009 H1N1 infection in order to determine whether this infection was related to a more severe illness than other causes of ILI. Neonatal characteristics and outcomes were very similar between both groups; with the exception of birth weight which was found to be on average 285 grams lower than women with ILI. The clinical significance of the weight difference detected in this observational trial needs to be evaluated in a larger trial aimed at evaluating and assessing fetal growth. Even after controlling for possible confounders, the difference in birth weight persisted. Although this trial lacks a normal control group, the difference noted in birth weights does appear to be significant. During 2005, the nationwide mean birth weight reported in the US was 3389 grams 16, a value that closely resembles the mean birth weight reported in our ILI group and is over 200 grams greater than mean birth weight reported in our H1N1 cohort.

Prior influenza pandemics have reported adverse fetal outcomes in women infected by the virus. Increased rates of preterm deliveries and pregnancy losses are always a concern with maternal influenza infection 7. Influenza preparedness forums have recommended that increased resources be available to meet the demand of increased pregnancy losses and preterm births 5. Although a comparison of our cohort to a group not affected with flu symptoms was not included in the study, the overall preterm rate of 5% seen in our study population is well below the nationally reported average of 12.7% 12. The lower rate of preterm birth observed in our group could be explained by the relatively small sample size. Siston et al evaluated 788 pregnant women across the United States with 2009 H1N1 infection and found a preterm delivery rate of 30.2% 11. The majority of the subjects enrolled in our study was treated as outpatients and theoretically had a less severe disease clinically, thus contributing to the decrease in our observed incidence of preterm delivery. A review of cases involving critically ill pregnant and postpartum women in Australia and New Zealand revealed 36 out of 60 newborns evaluated were born prior to 36 weeks gestation 8. Cases from hospitalized women with moderate or severe disease in the New York City an average gestational age of 34.8 weeks at delivery for women cataloged as having severe disease 9. Both studies also revealed that critically ill pregnant women have a higher percentage of severe neonatal outcomes including admission to NICU and neonatal death 8, 9. Strains of influenza that are more aggressive and virulent than seasonal flu have been shown to infect trophoblasts 14. This placental infection of highly virulent flu strains creates a biologically plausible route for vertical transmission along with contributing to a decrease in fetal growth seen in infants of mothers with 2009 H1N1 infection.

Infection with 2009 H1N1 has been shown to have clinically different patterns when compared to seasonal influenza, including more severe clinical outcomes in pregnant patients. The limited numbers of studies that report neonatal outcomes from maternal 2009 H1N1 infection do seem to differ from outcomes reported from investigations during seasonal flu outbreaks. In a study conducted in 1,838 pregnant women with seasonal influenza between 1980 and 1996, the authors found no increase in the prevalence of pregnancy complications when compared to the general obstetrical population 17. Using patients enrolled in the Tennessee Medicaid program, Hartert et al studied 294 women with seasonal influenza. They did not detect any difference in birth weight, preterm delivery rate or fetal death in women with singleton pregnancies diagnosed with seasonal influenza or pneumonia when compared to a matched cohort 3.

The impact that maternal influenza infection might have on the route of delivery is not well studied. Cases of pregnant women reported to the CDC during 2009 revealed that of the cases in which mode of delivery was reported, an unusually high number of women underwent cesarean section delivery 11. Sixty-four percent of women admitted to the ICU with severe disease were delivered via cesarean section 8. This is likely an effect of deteriorating maternal condition that negatively impacts overall fetal status. The relatively small number of patients evaluated in these studies limits the interpretation of the results.

Determining the impact of seasonal and non-seasonal influenza infection on neonates requires further evaluation. The prospective nature of our design study adds strength to the reported findings. Most studies reporting on outcomes from 2009 H1N1 infections have focused on severely ill patients admitted to intensive care units or hospitalized patients. The inclusion of women in our study that were treated in an outpatient setting adds important clinical knowledge to practitioners and allows the study to be more generalizable. The lack of studies focused exclusively on neonatal outcomes creates a gap of knowledge that could impact management decisions and prevention strategies.

The limitations of our study should also be noted. Our limited sample size does not allow for evaluation of rare events. Specific conclusions on treatment strategies cannot be developed from such a small cohort. The impact of vaccination and early antiviral therapy was not evaluated and is an area that deserves further study. The lack of long term follow-up on our neonates also precludes us from developing conclusion of the impact of this disease further in life.

In conclusion, the impact of maternal infection with influenza on neonatal outcomes has not been well-studied. Specific studies evaluating neonatal outcomes are needed to tackle some unanswered questions. Long term follow-up of infants born to women with influenza infection should also be undertaken. Different strains of influenza virus may have different impacts on overall outcomes and should be considered when evaluating influenza in pregnancy. With new treatment options available and improved overall health care, the historical implications of influenza infection on pregnant women may now differ from current trends.

Acknowledgment

Financial Support: Time spent on this study was partially supported with funding from 1K23HD062340-01 grant (BL Anderson – PI).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.WHO. http://www.euro.who.int/en/what-we-publish/information-for-the-media/sections/press-releases/2009/06/influenza-a-h1n1-who-announces-pandemic-alert-phase-6,of-moderate-severity.

- 2.Freeman DW, Barno A. Deaths from Asian influenza associated with pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1959;78:1172–1175. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(59)90570-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartert TV, Neuzil KM, Shintani AK, et al. Maternal morbidity and perinatal outcomes among pregnant women with respiratory hospitalizations during influenza season. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1705–1712. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(03)00857-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris J. Influenza in pregnant women. JAMA. 1919;72:978–980. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Macfarlane K, Cragan JD, Williams J, Henderson Z. Pandemic influenza and pregnant women: summary of a meeting of experts. Am J Public Health. 2009;99 Suppl 2:S248–S254. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamieson DJ, Theiler RN, Rasmussen SA. Emerging infections and pregnancy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1638–1643. doi: 10.3201/eid1211.060152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Rasmussen SA, et al. H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the USA. Lancet. 2009;374:451–458. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Critical illness due to 2009 A/H1N1 influenza in pregnant and postpartum women: population based cohort study. BMJ. 340:c1279. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Creanga AA, Johnson TF, Graitcer SB, et al. Severity of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 115:717–726. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d57947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louie JK, Acosta M, Jamieson DJ, Honein MA. Severe 2009 H1N1 influenza in pregnant and postpartum women in California. N Engl J Med. 362:27–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siston AM, Rasmussen SA, Honein MA, et al. Pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus illness among pregnant women in the United States. JAMA. 303:1517–1525. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton BE, Minino AM, Martin JA, Kochanek KD, Strobino DM, Guyer B. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2005. Pediatrics. 2007;119:345–360. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irving WL, James DK, Stephenson T, et al. Influenza virus infection in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy: a clinical and seroepidemiological study. BJOG. 2000;107:1282–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu J, Xie Z, Gao Z, et al. H5N1 infection of the respiratory tract and beyond: a molecular pathology study. Lancet. 2007;370:1137–1145. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61515-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Acs N, Banhidy F, Puho E, Czeizel AE. Maternal influenza during pregnancy and risk of congenital abnormalities in offspring. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2005;73:989–996. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donahue SM, Kleinman KP, Gillman MW, Oken E. Trends in birth weight and gestational length among singleton term births in the United States: 1990–2005. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:357–364. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cbd5f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Acs N, Banhidy F, Puho E, Czeizel AE. Pregnancy complications and delivery outcomes of pregnant women with influenza. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;19:135–140. doi: 10.1080/14767050500381180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]