Abstract

Prasaplai is a medicinal plant mixture that is used in Thailand to treat primary dysmenorrhea, which is characterized by painful uterine contractility caused by a significant increase of prostaglandin release. Cyclooxygenase (COX) represents a key enzyme in the formation of prostaglandins. Former studies revealed that extracts of Prasaplai inhibit COX-1 and COX-2. In this study, a comprehensive literature survey for known constituents of Prasaplai was performed. A multiconformational 3D database was created comprising 683 molecules. Virtual parallel screening using six validated pharmacophore models for COX inhibitors was performed resulting in a hit list of 166 compounds. 46 Prasaplai components with already determined COX activity were used for the external validation of this set of COX pharmacophore models. 57% of these components were classified correctly by the pharmacophore models. These findings confirm that the virtual approach provides a helpful tool (i) to unravel which molecular compounds might be responsible for the COX-inhibitory activity of Prasaplai and (ii) for the fast identification of novel COX inhibitors.

Keywords: Prasaplai, Traditional medicine of Thailand, Natural products, Cyclooxygenase, Pharmacophore, Virtual screening

Introduction

Virtual screening techniques are very common and widespread in medicinal chemistry (Ekins et al. 2007b,a; Kirchmair et al. 2008). The general goal of applying such methods is to filter large compound databases in silico in order to focus experimental efforts on those candidates which are most promising for showing the desired pharmacological effect. Today, the pharmacophore concept is one of the most widely established methods for virtual screening (Langer et al. 2006; Leach et al. 2010). By definition, a pharmacophore is the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger or block its biological response (Wermuth et al. 1998). Common pharmacophoric features include hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, hydrophobic interactions, aromatic ring systems, positively or negatively ionizable functions, and data on their location in the three-dimensional (3D) space. Moreover, pharmacophore models can be sterically restricted by “forbidden” areas, so-called exclusion volumes, and shapes, of which the latter are usually derived from highly active ligands. One pharmacophore model usually represents one certain binding mode to a receptor or an enzyme. If a compound fulfils the requirements of a pharmacophore model, it is more likely to show biological activity than compounds that do not fit into the model.

Originally, pharmacophore-based virtual screening has been developed to find bioactive synthetic compounds. More recently, this approach has also shown to be valuable in the field of natural products for the identification of bioactive constituents (Rollinger et al. 2006, 2008). In earlier studies single pharmacophore models were used for the virtual screening of natural product (NP) databases (Rollinger et al. 2004, 2005). Technological evolution enabled upscaling of the virtual screening protocols using parallel screening (PS) techniques (Rollinger 2009; Rollinger et al. 2009). In pharmacophore-based PS, single compounds or small databases are virtually screened against a series of pharmacophore models, aiming at the prediction of pharmacological activity profiles of these molecules (Kirchmair et al. 2008; Rollinger 2009). Herein we present a further application scenario of PS, i.e. the search for structurally diverse natural compounds with a defined molecular mode of action.

Traditional medicine often uses plant mixtures which contain hundreds of compounds from different biosynthetic origin and different chemical scaffolds. In this study, we selected Prasaplai, a Thai traditional medicine, as a sample for the application of PS because (i) it is a complex mixture of NPs, (ii) it is used in traditional medicine to treat inflammatory processes (List of Herbal Medicinal Products A.D. 2006), and (iii) its anti-inflammatory activity has already been confirmed. The hexane extract (25 μg ml−1) inhibited both cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 and COX-2 up to 64.43 and 84.50%, respectively (Nualkaew et al. 2005) suggesting that Prasaplai acts at least partially via the inhibition of COX enzymes.

Prasaplai is composed of twelve ingredients: ten crude plant drugs (the roots of Acorus calamus L., the bulbs of Allium sativum L., the pericarps of Citrus hystrix DC., the rhizomes of Curcuma zedoaria Roscoe, the bulbs of Eleutherine americana Merr, the seeds of Nigella sativa L., the fruits of Piper chaba Hunt, the fruits of Piper nigrum L., the rhizomes of Zingiber cassumunar Roxb., and the rhizomes of Zingiber officinale Roscoe) and two pure compounds (sodium chloride and camphor). The main component of Prasaplai is Zingiber cassumunar rhizome; it makes up to 50% (w/w) of the mixture. Camphor makes up to 0.6% (w/w) while the other components are equal in weight. Prasaplai is widely used by Thai traditional doctors for relieving primary dysmenorrhea and adjusting the cycle of menstruation (List of Herbal Medicinal Products A.D. 2006; Nualkaew et al. 2004).

The correlation between gynecological disorders and the release of inflammatory mediators was reviewed recently (Hayes and Rock 2002; Connolly 2003). Primary dysmenorrhea is characterized by painful uterine contractility caused by a significant increase of prostaglandin release compared with normal menstruation. Since COX-1 and COX-2 represent key enzymes in the formation of prostaglandins, inhibitors of COX are effective therapeutics and the treatment of first choice.

COX-1 and COX-2 are ideal model targets for a case study since X-ray crystal structures with bound inhibitors, a large number of known active ligands, and datasets for theoretical model validation are available. In our study, a set of five structure-based models and one ligand-based pharmacophore model for COX inhibitors were applied to the constituents of Prasaplai in order to (i) unravel which compounds of Prasaplai might be responsible for the COX-inhibitory activity and (ii) to validate our pharmacophore models using published knowledge about constituents of this herbal remedy.

Materials and methods

General experimental procedures

Molecular modeling studies were performed on an Intel Pentium Core 2 Duo 6400 equipped with 1 GB RAM running Linux Fedora Core 6. PS calculations were carried out on an Intel Centrino Core 2 Duo T7500 with 2 GB RAM running Windows XP. For pharmacophore model generation and validation and PS experiments the software programs LigandScout 1.03 (Inte:Ligand GmbH, Vienna, Austria, 2006), Catalyst 4.11 (Accelrys Software Inc., San Diego, USA, 2005), and Discovery Studio 2.1 (Accelrys Software Inc., San Diego, USA, 2007) were used.

Pharmacophore modeling

Pharmacophore models may be obtained either via the structure-based or via the ligand-based approach. Structure-based pharmacophore model generation uses 3D structural information on the target protein, which is usually obtained from X-ray crystallography. Protein structures in complex with ligands are publicly available via the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (Berman et al. 2003). Possible chemical interactions between the ligand(s) and the macromolecule are analyzed, and pharmacophore features are placed where interactions are observed. For the ligand-based approach, only information on known biological activity of ligands is required. An algorithm defines common chemical features of a set of bioactive molecules (Schuster and Wolber 2010). For this study, both approaches were applied. All generated models were theoretically evaluated if they found clinically used COX inhibitors and excluded inactive compounds from the hit list. The best six models were used for further experiments. A more detailed description of the pharmacophore model generation and validation and the PS procedure is provided in part I of this study (Schuster et al. 2010).

NPs database generation

An extensive literature survey was performed in order to collect compounds of the different plants contained in the Prasaplai mixture. These compounds were stored as 3D structure models in a database, the so-called Prasaplai database. When stereochemistry was not completely specified, all possible stereoisomers were built and stored. Since it is not clear, which 3D conformations the molecules would adopt in the interaction with the target protein, structures were handled as collections of low-energy 3D conformers.

Parallel virtual screening

The structures in the Prasaplai database were virtually screened against the pharmacophore model set. A compound was considered to be a hit only if all functions of at least one pharmacophore model were mapped.

Results and discussion

Generation and validation of COX inhibitors pharmacophore models

Several PDB complexes were used as templates for exhaustive pharmacophore model generation. Suitable validation processes were applied to the models to select diverse ones with high enrichment factors and high restrictivity. This approach led to a final collection of five structure-based pharmacophore models of COX enzymes, which were built based upon atomic coordinates published in PDB entries representing protein/ligand complexes (Table 1). Since this structure-based model set was not able to recognize actives of diverse chemical structures, a ligand-based pharmacophore model was developed that was able to identify other scaffolds as well. This model was generated by aligning the bioactive conformations of (S)-flurbiprofen and SC-558 (Schuster et al. 2010).

Table 1.

COX Inhibitor Pharmacophore Models used for PS of Prasaplai Components.

| 3D charta |  |

|

|

| Name | 1cqe-1 | 1pge-2-s | 2ayl-1 |

| PDB entry | 1cqe (Picot et al. 1994) | 1pge (Loll et al. 1996) | 2ayl (Gupta et al. 2006) |

| Complex | COX-1/flurbiprofen | COX-1/iodosuprofen | COX-1/flurbiprofen |

| 3D charta |  |

|

|

| Name | 4cox-2 | 6cox-1-s | Ligand-based model |

| PDB entry | 4cox (Kurumbail et al. 1996) | 6cox (Kurumbail et al. 1996) | – |

| Complex | COX-2/indometacin | COX-2/S-558 | – |

3D chart of pharmacophore model with underlying COX ligand(s). Exclusion volumes are omitted for better transparency. Instead, the surface of the binding pocket is depicted to show the steric constraints of the model.

Generation and PS of the Prasaplai database

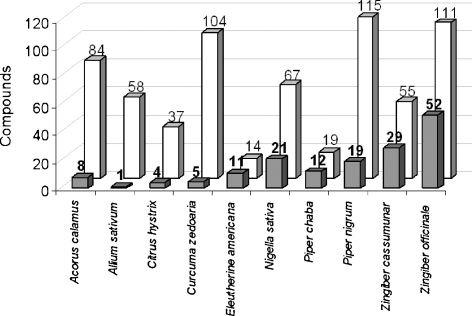

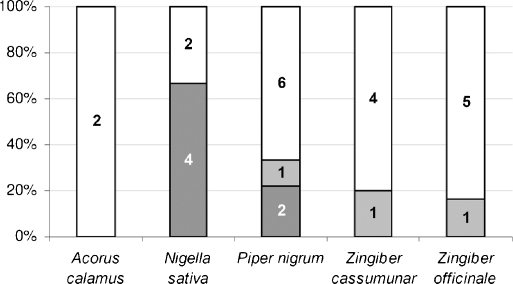

A comprehensive literature survey for known components of Prasaplai was performed. 3D structures of these compounds were collected resulting in a molecular library containing a total number of 683 NPs. The Prasaplai database was subjected to a PS using the five structure-based and the ligand-based COX pharmacophore models. This process resulted in a virtual hit list containing 166 potential COX inhibitors. Fig. 1 shows the numbers of known components of the different plant ingredients of Prasaplai and the numbers of virtual hits (VH) retrieved from the PS.

Fig. 1.

Number of VH obtained from PS (grey columns) vs. number of known components of the plants Prasaplai is composed of (white columns).

Compound evaluation procedure

The obtained VH were critically analyzed according to their COX-inhibitory activity that is already evident from literature. For 25 VH literature data about their COX-inhibitory activity were available (Table 2). These compounds are ingredients from five of the ten plants Prasaplai is composed of, i.e. Acorus calamus, Nigella sativa, Piper nigrum, Zingiber cassumunar and Zingiber officinale. Consequently, the pharmacophore model set was validated using compounds of these five plants. All known constituents (VH as well as non-VH, i.e. structures that were not recognized by any of the six pharmacophore models) of these plants were evaluated on available COX-inhibitory activity. Only those structures were considered for the validation process and are described in detail in this study for which published data about the inhibition of COX enzymes are available. The relevant non-VH are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

VH with published COX-inhibitory activities.

| Compound | Prasaplai plant origin | COX-1 inhibitory activity | COX-2 inhibitory activity | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palmitic acid | Acorus calamus, Nigella sativa | No inhibition (390 μM) (Henry et al. 2002) | No inhibition (390 μM) (Henry et al. 2002) | |

| Asaraldehyde | Acorus calamus | 3.32% (510 μM) (Momin et al. 2003) | 52.69% (510 μM) (Momin et al. 2003) |  |

| α-Asarone | Acorus calamus | 46.15% (480 μM) (Momin et al. 2003) | 64.39% (480 μM) (Momin et al. 2003) |  |

| Myristic acid | Nigella sativa | No inhibition (438 μM) (Henry et al. 2002) | No inhibition (438 μM) (Henry et al. 2002) | |

| Pentadecanoic acid | Nigella sativa | No inhibition (413 μM) (Henry et al. 2002) | No inhibition (413 μM) (Henry et al. 2002) | |

| α-Linolenic acid | Nigella sativa, Zingiber officinale | ∼93% (359 μM) (Henry et al. 2002), IC50 = 52 μM (Jager et al. 2008) | ∼96% (359 μM) (Henry et al. 2002), IC50 = 12 μM (Jager et al. 2008) |  |

| Palmitoleic acid | Nigella sativa | ∼11% (393 μM) (Henry et al. 2002) | No inhibition (393 μM) (Henry et al. 2002) |  |

| Linoleic acid | Nigella sativa | ∼87% (357 μM) (Henry et al. 2002), IC50 = 85 μM (Jager et al. 2008), IC50 = 52.2 μM (Su et al. 2002b) | ∼94% (357 μM) (Henry et al. 2002), IC50 = 0.6 μM (Jager et al. 2008), IC50 = 1.9 μM (Su et al. 2002b) |  |

| Oleic acid | Nigella sativa | 25% (354 μM) (Henry et al. 2002), 45.32% (354 μM) (Momin et al. 2003), IC50 = 85.3 μM (Su et al. 2002b) | Little or no activity (354 μM) (Henry et al. 2002), 68.41% (354 μM) (Momin et al. 2003), IC50 = 0.7 μM (Su et al. 2002b) |  |

| Stearic acid | Nigella sativa | No inhibition (352 μM) (Henry et al. 2002; Su et al. 2002b) | No inhibition (352 μM) (Henry et al. 2002; Su et al. 2002b) |  |

| Erucic acid | Nigella sativa | No inhibition (295 μM) (Henry et al. 2002) | No inhibition (295 μM) (Henry et al. 2002) |  |

| Eugenol | Nigella sativa, Piper nigrum | nda | IC50 = 129 μM (Huss et al. 2002) |  |

| Nonanoic acid | Piper nigrum | 29% (632 μM) (Henry et al. 2002) | Little or no activity (632 μM) (Henry et al. 2002) | |

| Octanoic acid | Piper nigrum | 12% (693 μM) (Henry et al. 2002) | No inhibition (693 μM) (Henry et al. 2002) | |

| Methyleugenol | Piper nigrum | 27.23% (100 μM) (Yano et al. 2006) | 42.64% (100 μM) (Yano et al. 2006) |  |

| (E)-4-(3,4-Dimethoxy-phenyl)but-3-en-1-yl acetate | Zingiber cassumunar | nd | IC50 > 50 μM (Han et al. 2005) | |

| 4-(2,4,5-Trimethoxy-phenyl)but-1,3-diene | Zingiber cassumunar | nd | IC50 = 14.97 μM (Han et al. 2005) |  |

| Trans-3-(3,4-dimethoxy-phenyl)-4-[(E)-3′,4′-dimethoxy-styryl]cyclohex-1-ene | Zingiber cassumunar | nd | IC50 = 2.71 μM (Han et al. 2005) |  |

| 4-(3,4-Dimethoxy-phenyl) but-1,3-diene | Zingiber cassumunar | nd | IC50 = 20.68 μM (Han et al. 2005) |  |

| (±)-Trans-3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxy-phenyl)-4-[(E)-3,4-dimethoxy-styryl]cyclo-hex-1-ene | Zingiber cassumunar | nd | IC50 = 3.64 μM (Han et al. 2005) |  |

| [6]-Shogaol | Zingiber officinale | nd | IC50 = 2.1 μM (Tjendraputra et al. 2001) | |

| [8]-Gingerdiol | Zingiber officinale | nd | IC50 = 12.5 μM (Tjendraputra et al. 2001) | |

| [6]-Paradol | Zingiber officinale | nd | IC50 = 24.5 μM (Tjendraputra et al. 2001) | |

| [8]-Gingerol | Zingiber officinale | nd | IC50 = 10.0 μM (Tjendraputra et al. 2001) | |

| [8]-Shogaol | Zingiber officinale | nd | IC50 = 7.2 μM (Tjendraputra et al. 2001) |

nd, not determined.

Table 3.

Non-VH with published COX-inhibitory activities.

| Compound | Prasaplai plant origin | COX-1 inhibitory activity | COX-2 inhibitory activity | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linalool | Acorus calamus, Nigella sativa, Piper nigrum, Zingiber officinale | Significant reduction of COX-2 expression and PGE2 formation only in the highest concentration (1000 μM) (Peana et al. 2006) |  |

|

| Limonene | Acorus calamus, Nigella sativa, Piper nigrum, Zingiber officinale, Zingiber cassumunar | IC50 > 100 μM (Gerhaeuser et al. 2003b) | nda |  |

| Thymoquinone | Nigella sativa | IC50 = 2.6 μM (Marsik et al. 2005) | IC50 = 0.3 μM (Marsik et al. 2005) |  |

| Thymohydroquinone | Nigella sativa | IC50 = 0.6 μM (Marsik et al. 2005) | IC50 = 0.1 μM (Marsik et al. 2005) |  |

| Dithymoquinone | Nigella sativa | IC50 > 100 μM (Marsik et al. 2005) | IC50 = 0.9 μM (Marsik et al. 2005) |  |

| Thymol | Nigella sativa | IC50 = 0.2 μM (Marsik et al. 2005) | IC50 = 1.0 μM (Marsik et al. 2005) |  |

| Piperine | Piper nigrum | 33.4% inhibition of PG biosynthesis at 37 μM (Wagner et al. 1986) | ||

| Nonanal | Piper nigrum | Reduction of arachidonic acid metabolites by 50% at ∼0.25 μM (Sakuma et al. 1997) | ||

| Trans-2-nonenal | Piper nigrum | Reduction of arachidonic acid metabolites by 50% at ∼0.25 μM (Sakuma et al. 1997) | ||

| Safrole | Piper nigrum | IC50 = 225 μM (Dewhirst 1980) | ||

| Spathulenol | Piper nigrum | 15% (454 μM) (Jayaprakasam et al. 2007) | 54% (454 μM) (Jayaprakasam et al. 2007) |  |

| Pellitorine | Piper nigrum | IC50 > 100 μM (Stohr et al. 1999) | ||

| 31% inhibition of COX (224 μM) (Muller-Jakic et al. 1994) | ||||

| Ledol | Piper nigrum | No inhibition of PG biosynthesis (37 μM) (Wagner et al. 1986) |  |

|

| (E)-4-(3,4-Dimethoxy-phenyl)but-3-en-1-ol | Zingiber cassumunar | nd | IC50 > 50 μM (Han et al. 2005) | |

| Vanillin | Zingiber cassumunar | IC50 > 50 μM (Su et al. 2002a) | IC50 > 50 μM (Su et al. 2002a) |  |

| Vanillic acid | Zingiber cassumunar | No inhibition (100 μM) (Gerhaeuser et al. 2003a) | nd |  |

| Curcumin | Zingiber cassumunar | IC50 = 18.8 μM (Gafner et al. 2004), IC50 = 50 μM (Handler et al. 2007), IC50 > 100 μM (Gerhaeuser et al. 2003b) | IC50 = 15.9 μM (Gafner et al. 2004), IC50 > 100 μM (Handler et al. 2007) | |

| β-Sitosterol | Zingiber officinale | No inhibition (241 μM) (Zhang et al. 2004) | 11% (241 μM) (Zhang et al. 2004), IC50 > 241 μM (Carcache-Blanco et al. 2006) |  |

| 6β-Hydroxystigmast-4-en-3-one | Zingiber officinale | nd | IC50 > 233 μM (Carcache-Blanco et al. 2006) |  |

| 1,8-Cineole | Zingiber officinale | IC50 > 500 μM (Dewhirst 1980) |  |

|

| Ascorbic acid | Zingiber officinale | IC50 > 100 μM (Gerhaeuser et al. 2003b) | IC50 = 3.70 μM (Fiebich et al. 2003) |  |

nd, not determined.

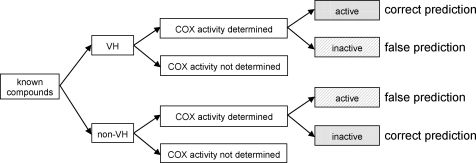

For the validation of the pharmacophore models there was not differentiated between COX-1 and COX-2 inhibition since the pharmacophore models are not selective for one isoform. According to their inhibition values for COX-1 and/or COX-2, the respective compounds were grouped into three categories: compounds with IC50 values below 25.0 μM, between 25.0 and 150.0 μM, and above 150.0 μM were considered as highly active, moderately active, and inactive, respectively. Highly or moderately active VH as well as inactive non-VH were assumed to be predicted correctly by the pharmacophore model set; inactive VH as well as highly or moderately active non-VH were assumed to be predicted incorrectly (Fig. 2). The correctness of the virtual prediction was determined for each of these five plants (Table 4). Fig. 3 shows the general workflow performed in this study.

Fig. 2.

Decision tree for validation of pharmacophore model set.

Table 4.

Determination of correctness of virtual prediction.

|

|

aThreshold: active, IC50 ≤ 150.0 μM; inactive, IC50 > 150.0 μM.

bGrey, correct prediction, active VH, inactive non-VH; hatched, false prediction, inactive VH, active non-VH.

cCorrectness of prediction referring to one plant. Number of correctly predicted structures/total number of structures × 100. Example Acorus calamus: three inactive VH, two inactive non-VH; two out of five structures predicted correctly; 40% correct prediction.

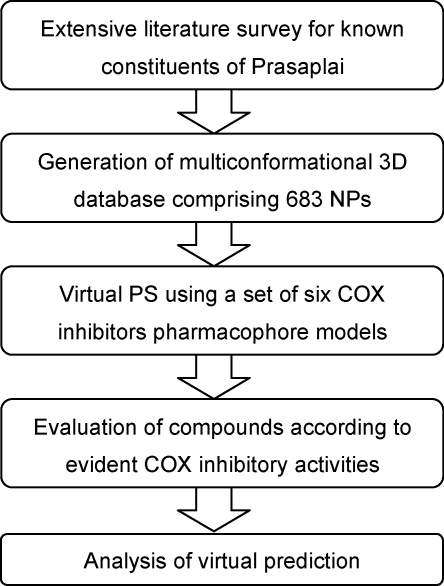

Fig. 3.

General workflow of the virtual PS approach performed in this study.

Zingiber cassumunar

Five VH of Zingiber cassumunar have already been evaluated on their COX-2 inhibitory activity (Table 2). Four compounds showed IC50 values on COX-2 of 2.71–20.68 μM. Only one compound was inactive. Therefore, 80% of the VH were predicted correctly.

For five non-VH published data about their ability to inhibit COX were available (Table 3). Limonene, (E)-4-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)but-3-en-1-ol and vanillin showed to be inactive on COX-1 and/or COX-2. There are many publications available describing the suppressive effect of curcumin on the expression of COX-2 leading to a decreased enzyme activity (Surh and Kundu 2007). However, the information regarding direct inhibition of COX is inconsistent, showing a range of IC50 from 15.9 to over 100 μM. Based on these data curcumin was considered as moderately active.

Except for curcumin, all known actives were found by the pharmacophore models. These compounds are even highly active COX inhibitors. The inactives were not recognized, thus predicted correctly, except for one compound, i.e. (E)-4-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)but-3-en-1-yl acetate.

Zingiber officinale

Six VH of Zingiber officinale have already been tested for their COX-inhibitory activity (Table 2). [6]-Shogaol, [8]-gingerdiol, [6]-paradol, [8]-gingerol, and [8]-shogaol showed IC50 values for COX-2 below 25.0 μM. Due to its high inhibitory activity especially on COX-2, α-linolenic acid was also considered to be highly active.

For six non-VH data on the inhibition of COX-1 and/or COX-2 were found (Table 3). According to biological tests, linalool, limonene, β-sitosterol, 6β-hydroxystigmast-4-en-3-one, and 1,8-cineole were classified as inactive. Ascorbic acid proofed to be inactive on COX-1 and active on COX-2. According to a third publication ascorbic acid induces the formation and the release of COX-catalyzed arachidonic acid metabolites via the activation of phospholipase A2 (Steinhour et al., 2008). Based on these inconsistent literate data ascorbic acid was considered as moderately active.

Except for ascorbic acid, all known actives of Zingiber officinale were predicted correctly (they are even highly active), and all known inactives were not recognized by the pharmacophore models. This rate of 92% correct prediction is notably high.

Nigella sativa

For ten VH of Nigella sativa data on their ability to inhibit COX were available (Table 2). According to their high inhibition described in literature, especially of COX-2, α-linolenic acid and linoleic acid were considered as highly active. Palmitoleic acid, myristic acid, pentadecanoic acid, palmitic acid, stearic acid, and erucic acid showed little or no inhibitory activity on COX-1 and COX-2 and thus were considered as inactive. The available literature data for oleic acid were inconsistent. Therefore, it was considered as moderately active. Eugenol has been tested to be moderately active on COX-2.

The two highly active VH α-linolenic acid and linoleic acid belong to the class of oligo-unsaturated fatty acids. Although this substance class was not part of either model generation molecules or model refinement data sets, it was correctly identified by the pharmacophore models. This proofs that the model set can successfully perform the task of scaffold hopping. The other virtually predicted fatty acids have been determined to be inactive or have only weak inhibitory activity. Obviously, the pharmacophore models could not differentiate between these active and inactive compounds due to their high similarity. Basically, the substance class comprising active compounds was identified.

For six non-VH literature data about their COX-inhibitory activity were found (Table 3). Limonene and linalool have already been discussed above. The IC50 values of thymoquinone, thymohydroquinone and thymol were determined to be 0.2–2.6 μM for COX-1 and 0.1–1.0 μM for COX-2. Also dithymoquinone showed an IC50 value for COX-2 of <1.0 μM. Only its IC50 value for COX-1 was determined to be >100 μM. The fact that these highly active compounds were not recognized by the COX pharmacophore model set may be due to different reasons. Our hypothesis is that the structure-based models recognize mainly fatty acids, and since these hydroquinone derivatives belong to a totally different structure class, they were not found. For the ligand-based pharmacophore model an aromatic ring is mandatory which thymoquinone and dithymoquinone do not comprise. Thymohydroquinone and thymol are too small to fit into the model which results in the missing of one hydrophobic feature when mapping the structures into the pharmacophore model.

Piper nigrum

COX inhibition data were found for four VH of Piper nigrum (Table 2). Eugenol and methyleugenol showed to be moderately active. Nonanoic acid and octanoic acid were considered to be inactive. For nine non-VH, COX-inhibitory data were available in the literature (Table 3). Linalool, limonene, safrole, spathulenol, pellitorine, and ledol were described to show no or only weak COX inhibition. Thus they were considered as inactive. Piperine showed to be moderately active. Nonanal and trans-2-nonenal were considered as highly active.

In summary, three of those nine non-VH showed inhibitory activity on COX enzymes. We suggest that the structure-based pharmacophore models are very selective and thus do not recognize these substance classes. In the case of the ligand-based pharmacophore model piperine misses one hydrophobic feature. The problem of nonanal and trans-2-nonenal is that they do not feature an aromatic ring. If the aromatic ring in the ligand-based pharmacophore model was exchanged by a hydrophobic feature, these two structures were identified as hits. However, without the aromatic ring the model would be very unselective and PS of the Prasaplai database would retrieve a hit list comprising many false positive VH.

Acorus calamus

For three VH of Acorus calamus literature data about their COX-inhibitory activity were available (Table 2). Palmitic acid, α-asarone, and asaraldehyde were considered as inactive due to no or weak inhibition of COX-1 as well as COX-2. Only two non-VH have already been determined on their COX-inhibitory activity: linalool and limonene did not show significant inhibitory activity on COX (Table 3).

Allium sativum, Curcuma zedoaria

58 structures from Allium sativum were virtually screened using the pharmacophore model set. This approach resulted in one virtual hit (S-allylmercaptocysteine). Literature survey for COX inhibition data for this substance did not retrieve any information. The virtual screening of the 104 structures from Curcuma zedoaria resulted in a hit list comprising five structures. Also for these five compounds no literature data about their COX-inhibitory activity were available. COX-inhibitory effects of plant extracts have been reported (Sendl et al. 1992; Ali et al. 1993; Ali 1995; Tohda et al. 2006). However, since there was no information available about the correctness of the prediction of those VH, compounds of these plants were not used for the validation of the pharmacophore models.

Citrus hystrix, Eleutherine americana, Piper chaba

The PS of the 37 structures from Citrus hystrix, the 14 from Eleutherine americana and the 18 from Piper chaba with the six pharmacophore models resulted in hit lists comprising four, eleven, and twelve structures, respectively. Since literature data on COX inhibition for any of those hits were not available, compounds of these plants were not included in the validation process.

Camphor, sodium chloride, artefacts

Camphor and sodium chloride are the two pure compounds in the Prasaplai mixture. Therefore camphor was also added to the molecule library that was virtually screened with the pharmacophore models, as well as the three artefacts that originate during storage of Prasaplai. These fatty acid esters arise from the interaction of compounds of Nigella sativa and Zingiber cassumunar (Nualkaew et al. 2004). Camphor was not recognized by the pharmacophore models, the three artefacts were found. However, their COX-inhibitory activity has not been determined yet.

Summary of pharmacophore models validation

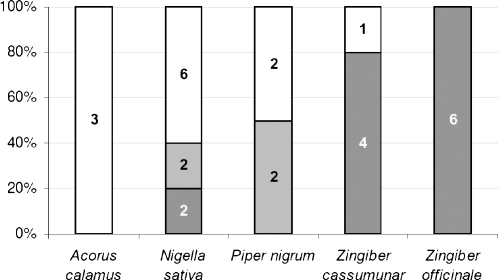

Basically, the compounds with known activity on COX were often predicted correctly by the pharmacophore models (Fig. 4, VH; Fig. 5, non-VH). In the case of Acorus calamus, 40% of the compounds with known activity on COX were predicted correctly, i.e. two inactives out of five compounds with experimentally determined COX-inhibitory activity. For the compounds of Nigella sativa, Piper nigrum, and Zingiber cassumunar with known activity on COX-38, 62, and 80% correct prediction was obtained, respectively. For the compounds of Zingiber officinale the highest rate of correct prediction was achieved: eleven out of twelve components, i.e. 92%. Only one active non-VH, ascorbic acid, was not recognized by the pharmacophore model set, thus predicted incorrectly.

Fig. 4.

Numbers of VH included in pharmacophore models validation. Threshold: highly active, IC50 < 25.0 μM (dark grey); moderately active, IC50 = 25.0–150.0 μM (light grey); inactive, IC50 > 150.0 μM (white).

Fig. 5.

Numbers of non-VH included in pharmacophore models validation. Threshold: highly active, IC50 < 25.0 μM (dark grey); moderately active, IC50 = 25.0–150.0 μM (light grey); inactive, IC50 > 150.0 μM (white).

In total, from the 25 VH with known activity on COX, eleven were reported to be highly active, three moderately active, and eleven inactive. This gives a rate of correct prediction of 56%. Further, out of the 21 non-VH already determined for their COX activity, six are highly active, three are moderately active and twelve non-VH are inactive, resulting in 57% of correct prediction. Thus, also the combination of these VH and non-VH provides a total rate of correct prediction of 57%, i.e. 26 out of 46 compounds.

Discussion

In general, random screening or high-throughput screening of unbiased sets of compounds results in estimated average hit rates of 0.05–0.2%. With virtual screening techniques average hit rates of 5–25% are commonly gained (Oprea 2004). When interpreting these values it has to be considered that the hit rates are highly dependent on the target and the quality of the pharmacophore models, which again are closely related to the available structural information used as starting point for model generation.

On average the virtual prediction of Prasaplai components was satisfactory. Although 0% of the VH of Acorus calamus was predicted correctly (none of the three VH was considered to be active), rates of correct prediction of 40, 50 and even 80% could be achieved by the VH of Nigella sativa, Piper nigrum, and Zingiber cassumunar, respectively. The highest rate was obtained by the VH of Zingiber officinale (100%). The resulting average rate of correct prediction of 56% is comparable to published virtual prediction values in the field of pharmaceutical chemistry (Doman et al. 2002).

The evaluation of the performed computational approach underlying this study is influenced by different factors. In many cases negative results from biological testing are not published. We suggest that this is the reason we found only a small number of inactive substances in literature (23 vs. 23 actives). Another problem represents the reliability of literature data. Even if the data are correct, the authors of the publications used different test systems, which results in the problem that inhibition values cannot be directly compared. Even literature data regarding one compound are often inconsistent.

In general, one reason for not finding actives might be the fact that a pharmacophore model only represents one binding mode. Consequently, the inhibitory activity of a compound might be due to another binding mode which is not covered by the pharmacophore model set.

However, by the application of the Prasaplai components to PS with a set of COX pharmacophore models, molecular compounds were identified that are at least in part responsible for the COX-inhibitory activity of the Thai mixture. Furthermore, the results of the pharmacophore models validation with Prasaplai components confirm that – in comparison to a random screening approach – the virtual approach is able to increase the chance to find actives.

Conclusion

Computational approaches are effective strategies in drug discovery. They have the potential to decrease cost and time of drug development. In this study, the applicability and efficiency of pharmacophore-based PS was shown when searching for bioactive NPs. In this application scenario, active compounds were successfully identified from a structurally diverse mixture. In total, 57% of the compounds in the validation set were predicted correctly by the COX pharmacophore models. Thus, the pharmacophore-based virtual PS revealed as a powerful tool to identify COX inhibitors from a complex mixture of NPs. We suggest that this approach can be applied to several kinds of plants and plant mixtures and is not limited to COX enzymes but can also be used for other targets.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Research Network – project “DNTI” S10703-B03 granted by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), by a Young Talents Grant (Nachwuchsförderung) by the University of Innsbruck to D.S., and by the Thailand Research Fund (The Royal Golden Jubilee Ph.D. Program, grant PHD/0202/2547).

References

- Ali M. Mechanism by which garlic (Allium sativum) inhibits cyclooxygenase activity. Effect of raw versus boiled garlic extract on the synthesis of prostanoids. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 1995;53:397–400. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(95)90102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M., Angelo-Khattar M., Farid A., Hassan R.A., Thulesius O. Aqueous extracts of garlic (Allium sativum) inhibit prostaglandin synthesis in the ovine ureter. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 1993;49:855–859. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(93)90210-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman H., Henrick K., Nakamura H. Announcing the worldwide Protein Data Bank. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:980. doi: 10.1038/nsb1203-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carcache-Blanco E.J., Cuendet M., Park E.J., Su B.N., Rivero-Cruz J.F., Farnsworth N.R., Pezzuto J.M., Douglas Kinghorn A. Potential cancer chemopreventive agents from Arbutus unedo. Nat. Prod. Res. 2006;20:327–334. doi: 10.1080/14786410500161205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly T.P. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in gynecologic practice. Clin. Med. Res. 2003;1:105–110. doi: 10.3121/cmr.1.2.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewhirst F.E. Structure–activity relationships for inhibition of prostaglandin cyclooxygenase by phenolic compounds. Prostaglandins. 1980;20:209–222. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(80)80040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doman T.N., McGovern S.L., Witherbee B.J., Kasten T.P., Kurumbail R., Stallings W.C., Connolly D.T., Shoichet B.K. Molecular docking and high-throughput screening for novel inhibitors of protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:2213–2221. doi: 10.1021/jm010548w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekins S., Mestres J., Testa B. In silico pharmacology for drug discovery: applications to targets and beyond. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007;152:21–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekins S., Mestres J., Testa B. In silico pharmacology for drug discovery: methods for virtual ligand screening and profiling. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007;152:9–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiebich B.L., Lieb K., Kammerer N., Hull M. Synergistic inhibitory effect of ascorbic acid and acetylsalicylic acid on prostaglandin E2 release in primary rat microglia. J. Neurochem. 2003;86:173–178. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gafner S., Lee S.K., Cuendet M., Barthelemy S., Vergnes L., Labidalle S., Mehta R.G., Boone C.W., Pezzuto J.M. Biologic evaluation of curcumin and structural derivatives in cancer chemoprevention model systems. Phytochemistry. 2004;65:2849–2859. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhaeuser C., Alt A.P., Klimo K., Knauft J., Frank N., Becker H. Isolation and potential cancer chemopreventive activities of phenolic compounds of beer. Phytochem. Rev. 2003;1:369–377. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhaeuser C., Klimo K., Heiss E., Neumann I., Gamal-Eldeen A., Knauft J., Liu G.Y., Sitthimonchai S., Frank N. Mechanism-based in vitro screening of potential cancer chemopreventive agents. Mutat. Res. 2003;523-524:163–172. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00332-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta K., Selinsky B.S., Loll P.J. 2.0 angstroms structure of prostaglandin H2 synthase-1 reconstituted with a manganese porphyrin cofactor. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. D. 2006;62:151–156. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han A.R., Kim M.S., Jeong Y.H., Lee S.K., Seo E.K. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory phenylbutenoids from the rhizomes of Zingiber cassumunar. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2005;53:1466–1468. doi: 10.1248/cpb.53.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handler N., Jaeger W., Puschacher H., Leisser K., Erker T. Synthesis of novel curcumin analogues and their evaluation as selective cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) inhibitors. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2007;55:64–71. doi: 10.1248/cpb.55.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes E.C., Rock J.A. COX-2 inhibitors and their role in gynecology. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2002;57:768–780. doi: 10.1097/00006254-200211000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry G.E., Momin R.A., Nair M.G., Dewitt D.L. Antioxidant and cyclooxygenase activities of fatty acids found in food. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002;50:2231–2234. doi: 10.1021/jf0114381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huss U., Ringbom T., Perera P., Bohlin L., Vasange M. Screening of ubiquitous plant constituents for COX-2 inhibition with a scintillation proximity based assay. J. Nat. Prod. 2002;65:1517–1521. doi: 10.1021/np020023m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager A.K., Petersen K.N., Thomasen G., Christensen S.B. Isolation of linoleic and alpha-linolenic acids as COX-1 and -2 inhibitors in rose hip. Phytother. Res. 2008;22:982–984. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaprakasam B., Alexander-Lindo R.L., DeWitt D.L., Nair M.G. Terpenoids from Stinking toe (Hymneae courbaril) fruits with cyclooxygenase and lipid peroxidation inhibitory activities. Food Chem. 2007;105:485–490. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchmair J., Distinto S., Schuster D., Spitzer G., Langer T., Wolber G. Enhancing drug discovery through in silico screening: strategies to increase true positives retrieval rates. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008;15:2040–2053. doi: 10.2174/092986708785132843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurumbail R.G., Stevens A.M., Gierse J.K., McDonald J.J., Stegeman R.A., Pak J.Y., Gildehaus D., Miyashiro J.M., Penning T.D., Seibert K., Isakson P.C., Stallings W.C. Structural basis for selective inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 by anti-inflammatory agents. Nature. 1996;384:644–648. doi: 10.1038/384644a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer T., Hoffmann R.D., Mannhold R. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2006. Pharmacophores and Pharmacophore Searches. [Google Scholar]

- Leach A.R., Gillet V.J., Lewis R.A., Taylor R. Three-dimensional pharmacophore methods in drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:539–558. doi: 10.1021/jm900817u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- List of Herbal Medicinal Products A.D. 2006. Chuoomnoom Sahakorn Karnkaset Publisher, Bangkok

- Loll P.J., Picot D., Ekabo O., Garavito R.M. Synthesis and use of iodinated nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug analogs as crystallographic probes of the prostaglandin H2 synthase cyclooxygenase active site. Biochemistry. 1996;35:7330–7340. doi: 10.1021/bi952776w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsik P., Kokoska L., Landa P., Nepovim A., Soudek P., Vanek T. In vitro inhibitory effects of thymol and quinones of Nigella sativa seeds on cyclooxygenase-1- and -2-catalyzed prostaglandin E2 biosyntheses. Planta Med. 2005;71:739–742. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-871288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momin R.A., De Witt D.L., Nair M.G. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes by compounds from Daucus carota L. seeds. Phytother. Res. 2003;17:976–979. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Jakic B., Breu W., Probstle A., Redl K., Greger H., Bauer R. In vitro inhibition of cyclooxygenase and 5-lipoxygenase by alkamides from Echinacea and Achillea species. Planta Med. 1994;60:37–40. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-959404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nualkaew S., Gritsanapan W., Petereit F., Nahrstedt A. New fatty acid esters originate during storage by the interaction of components in prasaplai, a Thai traditional medicine. Planta Med. 2004;70:1243–1246. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-835861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nualkaew S., Tiangda C., Gritsanapan W., Bauer R., Nahrstedt A. Book of Abstracts, 53rd Annual Congress of the Society for Medicinal Plant Research, P492. 2005. Confirmation of biological activities of Prasaplai, a Thai traditional medicine; p. 359. [Google Scholar]

- Oprea, T., 2004. Euro QSAR Istanbul, Istanbul.

- Peana A.T., Marzocco S., Popolo A., Pinto A. (−)-Linalool inhibits in vitro NO formation: probable involvement in the antinociceptive activity of this monoterpene compound. Life Sci. 2006;78:719–723. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picot D., Loll P.J., Garavito R.M. The X-ray crystal structure of the membrane protein prostaglandin H2 synthase-1. Nature. 1994;367:243–249. doi: 10.1038/367243a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollinger J.M. Accessing target information by virtual parallel screening—the impact on natural product research. Phytochem. Lett. 2009;2:53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Rollinger J.M., Bodensieck A., Seger C., Ellmerer E.P., Bauer R., Langer T., Stuppner H. Discovering COX-inhibiting constituents of Morus root bark: activity-guided versus computer-aided methods. Planta Med. 2005;71:399–405. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-864132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollinger J.M., Hornick A., Langer T., Stuppner H., Prast H. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of scopolin and scopoletin discovered by virtual screening of natural products. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:6248–6254. doi: 10.1021/jm049655r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollinger J.M., Langer T., Stuppner H. Strategies for efficient lead structure discovery from natural products. Curr. Med. Chem. 2006;13:1491–1507. doi: 10.2174/092986706777442075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollinger J.M., Schuster D., Danzl B., Schwaiger S., Markt P., Schmidtke M., Gertsch J., Raduner S., Wolber G., Langer T., Stuppner H. In silico target fishing for rationalized ligand discovery exemplified on constituents of Ruta graveolens. Planta Med. 2009;75:195–204. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1088397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollinger J.M., Stuppner H., Langer T. Virtual screening for the discovery of bioactive natural products. Prog. Drug Res. 2008;65(211):213–249. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7643-8117-2_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma S., Fujimoto Y., Tagano S., Tsunomori M., Nishida H., Fujita T. Effects of nonanal, trans-2-nonenal and 4-hydroxy-2,3-trans-nonenal on cyclooxygenase and 12-lipoxygenase metabolism of arachidonic acid in rabbit platelets. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1997;49:150–153. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1997.tb06770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster D., Waltenberger B., Kirchmair J., Distinto S., Markt P., Stuppner H., Rollinger J.M., Wolber G. Predicting cyclooxygenase inhibition by three-dimensional pharmacophoric profiling. Part I: model generation, validation and applicability in ethnopharmacology. Mol. Inf. 2010;29:75–86. doi: 10.1002/minf.200900071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster D., Wolber G. Identification of bioactive natural products by pharmacophore-based virtual screening. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2010;16:1666–1681. doi: 10.2174/138161210791164072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sendl A., Elbl G., Steinke B., Redl K., Breu W., Wagner H. Comparative pharmacological investigations of Allium ursinum and Allium sativum. Planta Med. 1992;58:1–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-961378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhour E., Sherwani S.I., Mazerik J.N., Ciapala V., O’Connor Butler E., Cruff J.P., Magalang U., Parthasarathy S., Sen C.K., Marsh C.B., Kuppusamy P., Parinandi N.L. Redox-active antioxidant modulation of lipid signaling in vascular endothelial cells: vitamin C induces activation of phospholipase D through phospholipase A2, lipoxygenase, and cyclooxygenase. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2008;315:97–112. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9793-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stohr J.R., Xiao P.G., Bauer R. Isobutylamides and a new methylbutylamide from Piper sarmentosum. Planta Med. 1999;65:175–177. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su B.N., Chang L.C., Park E.J., Cuendet M., Santarsiero B.D., Mesecar A.D., Mehta R.G., Fong H.H., Pezzuto J.M., Kinghorn A.D. Bioactive constituents of the seeds of Brucea javanica. Planta Med. 2002;68:730–733. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su B.N., Cuendet M., Farnsworth N.R., Fong H.H., Pezzuto J.M., Kinghorn A.D. Activity-guided fractionation of the seeds of Ziziphus jujuba using a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory assay. Planta Med. 2002;68:1125–1128. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-36354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surh Y.J., Kundu J.K. Cancer preventive phytochemicals as speed breakers in inflammatory signaling involved in aberrant COX-2 expression. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7:447–458. doi: 10.2174/156800907781386551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjendraputra E., Tran V.H., Liu-Brennan D., Roufogalis B.D., Duke C.C. Effect of ginger constituents and synthetic analogues on cyclooxygenase-2 enzyme in intact cells. Bioorg. Chem. 2001;29:156–163. doi: 10.1006/bioo.2001.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohda C., Nakayama N., Hatanaka F., Komatsu K. Comparison of anti-inflammatory activities of six curcuma rhizomes: a possible curcuminoid-independent pathway mediated by Curcuma phaeocaulis extract. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2006;3:255–260. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner H., Wierer M., Bauer R. Antiinflammatory drugs. Part 3. In vitro inhibition of prostaglandin biosynthesis by essential oils and phenolic compounds. Planta Med. 1986:184–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wermuth C.-G., Ganellin C.R., Lindberg P., Mitscher L.A. Glossary of terms used in medicinal chemistry (IUPAC recommendations 1997) Annu. Rep. Med. Chem. 1998;33:385–395. [Google Scholar]

- Yano S., Suzuki Y., Yuzurihara M., Kase Y., Takeda S., Watanabe S., Aburada M., Miyamoto K. Antinociceptive effect of methyleugenol on formalin-induced hyperalgesia in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006;553:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Jayaprakasam B., Seeram N.P., Olson L.K., DeWitt D., Nair M.G. Insulin secretion and cyclooxygenase enzyme inhibition by cabernet sauvignon grape skin compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004;52:228–233. doi: 10.1021/jf034616u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]