Abstract

Within the medical home, understanding the family and community context in which children live is critical to optimally promoting children’s health and development. How to best identify psychosocial issues likely to have an impact on children’s development is uncertain. Professional guidelines encourage pediatricians to incorporate family psychosocial screening within the context of primary care, yet few providers routinely screen for these issues. We propose applying the core principles of surveillance and screening, as applied to children’s development and behavior, to also address family psychosocial issues during health supervision services. Integrating psychosocial surveillance and screening into the medical home requires changes in professional training, provider practice, and public policy. The potential of family psychosocial surveillance and screening to promote children’s optimal development justifies such changes.

Keywords: family psychosocial issues, surveillance, screening, well-child care

INTRODUCTION

Family psychosocial issues have a major influence on children’s development.1 Certain factors contribute to children’s resiliency and healthy development, while other factors place children at increased risk of delayed or disordered development. In fact, many developmental and behavioral problems of young children correlate with the psychosocial status of their families.2

The term “family psychosocial issue,” as previously defined by Kelleher and Kemper, refers broadly to any “family factor that affects children’s health.”1,3 Family psychosocial issues can range from social needs (e.g., food insecurity, housing instability) to parent psychosocial problems (e.g., depression, intimate partner violence). Numerous studies have demonstrated the myriad of family psychosocial issues that place children at developmental risk (Table 1).4–13 Furthermore, the impact of these issues has been shown to be both cumulative and influenced by the age and developmental stage of the child.14–16

Table 1.

Examples of Family Psychosocial Issues, Association with Risk for Poor Child Outcomes, and Available Screening Tools

| Family Psychosocial Issue | Child Outcomes | Screening Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Food insecurity | Iron deficiency anemia, acute infections, depression, poor academic performance, poor social skills8,9,76,77 | U.S. Department of Agriculture 18-item Household Food Security scale (HFSS);78 30 day food security scale;79 Single question hunger screening tool;80 2-item food insecurity screen81 |

| Housing instability | Acute illness symptoms, chronic health problems, learning disabilities, behavioral problems, school failure1,12,13,82,83 | American Housing Survey84 |

| Intimate partner violence | Abuse, violent behavior, emotional, behavioral, social, and academic problems1,85,86 | Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS);87 Conflict Tactic Scale (CTS);88 Hurt, Insult, Threaten, and Scream (HITS);89 Partner Violence Screen (PVS)90; Women Abuse Screening Tool (WAST)91–93 |

| Maternal depression | Low-birth weight, developmental and behavioral problems, low self-esteem, psychiatric disorders1,94 | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI);95 Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale;96 Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Ham-D);97,98 Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2)99,100 |

| Parental history of abuse | Abuse, psychiatric disorders, behavioral problems1,101 | Items from the Kempe Family Stress Inventory (KFI)100,102 |

| Parental smoking | Asthma, respiratory infections, otitis media, sudden infant death syndrome103–105 | Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST);106 Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)107 |

| Parental substance abuse | Injury, learning disabilities, psychiatric disorders, neglect4,5,108–110 | ASSIST;106 Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT);111 CAGE questionnaire;112 Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST);113 Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST);114 TWEAK Test115 |

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) states that a family-centered medical home exists within a “community-based system.”17 Professional guidelines have encouraged providers to identify and intervene with various family issues, given their potential negative impact on child health and development.18–21 As stated in the AAP’s policy statement on the medical home, a key service for pediatricians is to interact with “community agencies to be certain that the special needs of the child and family are addressed.”22

Pediatricians, regardless of their practice setting and patient population, provide care to children who are exposed to family psychosocial issues and are in a unique position to develop partnerships with families.23 Yet studies suggest that providers are not effective in detecting many psychosocial issues.24,25 Providers most often cite barriers, including a lack of time, training, and knowledge of available resources.26,27 Child health providers may also question whether it is their prerogative to initiate discussion of parents’ psychosocial problems and whether they will offend parents by raising sensitive issues that are not solely child-directed topics.28,29 Finally, there are challenges to incorporating psychosocial screening within the current medical home structure.

Pediatric care models have focused on screening for specific family issues, such as parental smoking,30–32 intimate partner violence,33–35 and maternal depression36–40. To date, however, little guidance is available on how to best detect and intervene with the wide range of family psychosocial issues that influence children’s development. A new paradigm is needed to better address family psychosocial issues within the medical home.

SURVEILLANCE AND SCREENING

Expert opinion and research evidence support surveillance and screening as the process by which pediatric providers should monitor infants and young children for developmental delays.41 Surveillance is defined as “a flexible, longitudinal, and continuous process whereby knowledgeable professionals perform skilled observations during the provision of health care.”42 In contrast, screening involves the use of standardized tools, such as parent-completed questionnaires and professionally administered tests, at select ages. Surveillance and screening are guided by the developmental stage of the child and the concerns of the family and are used to monitor children’s development, provide anticipatory guidance, and initiate appropriate referrals. Both the Council on Children with Disabilities of the AAP and the Bright Futures Steering Committee have endorsed surveillance and screening as best practice.18,41

APPLYING SURVEILLANCE AND SCREENING TO FAMILY PSYCHOSOCIAL ISSUES

In contrast, there is currently no consensus on how best detect family psychosocial issues. We propose that the core components of surveillance and screening can also be effectively applied to family psychosocial issues to enhance the effectiveness of child health services.

Eliciting and Attending to the Parents’ Concerns

The AAP recognizes that parental concerns warrant prompt attention and recommends that providers elicit parental observations, experiences, and concerns by posing simple questions related to children’s development, learning, and behavior.18 A similar approach can be used to elicit and attend to parents’ concerns regarding family psychosocial issues. General queries could be posed at all well-child care visits, such as, “Tell me about your living situation,” and “How are your resources for caring for your baby?”18 The pediatrician may also ask, “Do you or your family have any needs with which I can help you?”

Maintaining a Family Psychosocial History

A family psychosocial history should be a key component of the well-child visit. The mnemonic, IHELLP, is one example of a strategy to assist providers with addressing family issues such as income, housing, education, legal status/immigration, literacy, and personal safety.43 Health information technology (e.g., templates) may also be useful. Like a developmental history, this history should be continually updated. This may be accomplished by asking, “Have there been any changes with your or your family’s needs since our last visit?”

Identifying the Presence of Risk and Protective Factors

Multiple, concurrent family problems increase a child’s risk for poor development and suggest the need for early intervention and close follow-up.15 Recognizing protective factors is also crucial to enable the provision of strength-based care to support the positive attributes of families.18,44

Documenting the Process and Findings

The medical record should document all family psychosocial surveillance and screening activities to ensure proper follow-up. The electronic medical record offers opportunities to develop templates specifically tailored to facilitate the documentation of family psychosocial issues and compile registries of families with common psychosocial issues. Of note, documentation of sensitive topics such as maternal depression and intimate partner violence may have medical-legal implications and require processes to ensure confidentiality and secure management.

Sharing Opinions and Concerns with Other Relevant Professionals

Bi-directional communication between pediatric providers and community social service agencies is important to promote a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to family psychosocial issues. Recent innovations in pediatric training acknowledge the importance of promoting collaboration and communication between child health providers and community-based organizations.45

ROLE OF SCREENING IN DETECTION OF FAMILY PSYCHOSOCIAL ISSUES

The AAP recommends the use of standardized screening tests at periodic well-child visits and when surveillance elicits concerns. Research has documented the efficacy of screening tests in the detection of family psychosocial issues.46 More than a decade ago, Kemper and Kelleher recommended incorporating global family psychosocial screening into pediatric practice.1 The authors concluded that doing so would legitimize these topics for discussion, enrich the clinical experience, and, ultimately, lead to more comprehensive pediatric care.

Achieving consensus on the importance of screening to strengthen longitudinal surveillance requires the resolution of such issues as which psychosocial issues should be the target of such screening. Certain guiding principles can inform pediatricians and their practices. Screening should be tailored to the most commonly identified issues in the community served by the medical home. For example, screening for public housing needs makes little sense in a practice that serves an upper middle class, suburban community. Screening should also be linked to the stages of a family’s development. Screening for childcare needs, for example, may no longer be as important once a child begins school. Relying on parents’ opinions and concerns to inform and, ultimately, determine the issues that are deemed important for screening is consistent with family-centered care and may promote families’ adherence to providers’ recommendations and referrals. Family psychosocial issues should be a target for screening when community resources are available to address these needs, since detection without referral to resources is only likely to increase frustration and may undermine the parent-provider relationship.47 This requires the medical home to be aware of available community resources prior to initiating routine screening.

Family psychosocial screening may consist of global screening, as well as more focused screening for certain, specific family psychosocial issues. While there are a variety of validated screening tools designed to detect such specific family psychosocial needs as maternal depression, intimate partner violence, etc. (Table 1), few global screening tools have been developed with demonstrated applicability to pediatric practice. Kemper’s original family psychosocial screening tool, since adopted for use by Bright Futures, screens for substance abuse, depression, intimate partner violence, parental history of abuse, social support, housing instability, low parental education, and unemployment.46

To date, two studies have demonstrated the impact of global screening for multiple family psychosocial problems at pediatric visits.46,48 Kemper found the use of a self-administered questionnaire increased the identification of family psychosocial problems among mothers attending a pediatric clinic.46 In the WE CARE project, conducted in an urban clinic, we found that parents completing a self-report screener for ten family psychosocial needs prior to the visit, along with providers’ access to family resource books containing information sheets listing available community resources (see Table 2), significantly increased identification and referrals to community agencies for basic needs such as food, employment, education, and housing.48 This model extended the provider’s role beyond surveillance and screening to include referring families to community-based services. Of note, this global screener identified relatively few sensitive family psychosocial problems to which our families were likely exposed, such as intimate partner violence and substance abuse.

Table 2.

Key Components of the WE CARE model

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. WE CARE survey instrument |

|

| 2. Family Resource Book (FRB) |

|

| 3. Provider training |

|

In contrast, studies have shown the impact of using specific screening tools for such sensitive family psychosocial issues as maternal depression,36–38 substance abuse,30–32 and intimate partner violence33–35. For example, Olson, et al., demonstrated that screening for maternal depression at well-child care visits using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) significantly increased the identification of mothers with major depressive disorder and pediatric interventions, including counseling and referral to community supports.38

Thus, research findings support the use of global screening tools to identify basic family issues, in combination with specific screening tools for sensitive problems, to enhance the effectiveness of longitudinal surveillance for psychosocial issues. We suggest that family psychosocial screening should occur: when surveillance detects a family psychosocial problem; during initial intake with any new family; with a newborn within the first six months of life; and periodically (e.g., annually) during well-child care visits, since family needs can change over time. Frequency of screening should be determined by the prevalence of psychosocial issues in the community and the capacity of the medical home staff.

INCORPORATING FAMILY PSYCHOSOCIAL SURVEILLANCE AND SCREENING WITHIN THE MEDICAL HOME

We acknowledge the challenges to incorporating psychosocial surveillance and screening in pediatric practice. The range of potential issues is extremely broad and families’ specific needs may vary by and within practice settings. Furthermore, resources are highly variable in their availability and require interaction with different service sectors. For example, certain basic issues such as housing, food, or employment are typically addressed by social service agencies, while other issues, such as maternal depression and substance abuse are typically treated by mental health professionals. Recommendations and strategies regarding the implementation of psychosocial surveillance and screening must, therefore, be sufficiently generic to accommodate the broad range of issues confronting families in different communities, while sufficiently substantive and specific to enable practices to better identify such issues and ensure the effective linkage of families to appropriate community resources.

Barriers to establishing family psychosocial surveillance and screening as the standard of care for child health care providers are similar to those impeding the widespread implementation of developmental surveillance and screening.26,49 Providers are expected to perform a litany of tasks during the well-child visit and adding another expectation to their busy agenda may seem unfeasible. For example, Holtrop and colleagues demonstrated that intimate partner violence (IPV) screening increased identification of women with IPV. To adequately address this issue with at-risk mothers, pediatricians must also have the capacity to make referrals to community resources and develop a safety plan. The effort required may well be daunting, given the time constraints of the typical well-child visit. This suggests that the current medical home model must be redesigned. Lack of reimbursement for such activities may make the costs of staffing and processes prohibitive. We suggest the following strategies for child health providers, professional organizations, and advocacy groups to facilitate the incorporation of surveillance and screening for family psychosocial issues within the medical home.

Increase Awareness by Child Health Providers and Parents that Family Psychosocial Issues are a Pediatric Issue

Although pediatric professional guidelines recommend discussion of family psychosocial issues at well-child visits,19–21 pediatricians may view these topics as beyond the scope of their implicit contract with families27,28. Professional organizations can take a leadership role in promoting this message nationally and locally, by emphasizing the correlation between family psychosocial issues and child health and the role of the pediatrician. Doing so may help promote acceptance of the detection of psychosocial issues as a core component of pediatric care.

Providers must also promote the message that parents can receive assistance and appropriate referrals to community resources within their child’s medical home. Parental awareness that these issues are a priority will encourage their participation in psychosocial surveillance and screening and increase their comfort with discussing sensitive issues. The longitudinal, therapeutic relationship between providers and parents should also enable discussions of difficult, sensitive issues.

Conduct Family Psychosocial Screening Prior to Patient Visits

Schor has recommended using time before the health supervision visit to perform screening tests.50 In our experience, parents were willing and able to complete a ten-item, written family psychosocial questionnaire in the waiting room.48 Currently, all parents accompanying their child for a well-child visit to the Harriet Lane Clinic of the Johns Hopkins Hospital complete a family psychosocial questionnaire that screens for basic needs and safety needs while awaiting their child’s pediatric provider. In addition to written surveys, newer technologies such as computer kiosks in the waiting room or administering surveys via telephone or the internet have also been shown to be useful.51–53

Ensure Reimbursement for Providers’ Early Detection and Intervention Activities

Without adequate reimbursement, universal adoption of family psychosocial surveillance and screening will not be feasible. Such reimbursement has facilitated the implementation of developmental surveillance and screening in a number of states.54 The AAP Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health has suggested using the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 99420 to support screening for post-partum depression as a measure of risk in the infant’s environment.55 Effective advocacy by pediatricians and organizations is critical to secure such policy change.

Promote Strategies to Strengthen Care Coordination to Link Families to Community Resources

The Institute of Medicine has identified care coordination as a key factor in improving the quality of health care.56 Pediatric care coordination is defined as a “patient- and family-centered, assessment driven, team-based activity designed to meet the needs of children and youth while enhancing the care-giving capabilities of families.”57 Experience with developmental surveillance and screening has documented the importance of care coordination in ensuring successful referrals. Even when at-risk children are successfully detected and community-based resources are identified, an average of 7 contacts may be required to successfully link children and families to services.58

Family psychosocial issues are likely to demand similar care coordination efforts. Parents report a disconnect between their child’s health provider and community-based services.59 In our experience in an inner-city pediatric clinic, we were impressed by the number of community resources that are available, free of charge, to families in need.48 When available, care coordinators can help to identify available community resources, along with monitoring adherence to recommendations and referrals, care planning (e.g., scheduling appointments), and providing feedback to parents, providers, and community resources.57 This team-based model of care allows busy providers to assist parents in connecting to resources, while not eroding clinical capacity. Unfortunately, few medical homes currently have care coordinators as members of their practice team and such functions are often assumed, when performed at all, by untrained and very busy support staff. In other practices, such functions are assumed by trained staff, such as social workers and nurses, often at the expense of their substantive clinical duties.

System change is necessary to fully enhance linkages between medical homes and community-based resources. Successful models of care coordination are currently being implemented, evaluated, and replicated in a variety of practice settings.60 Carolina Collaborative Community Care partners with other non-profit organizations to inform providers and families about resources and encourage referrals.61 Help Me Grow, a state-wide program in Connecticut currently being replicated in other states, assists with identifying children from birth to eight who are at increased risk for developmental and behavioral problems and connects them and their families to appropriate community resources.62,63 Key components include a free and confidential telephone access point which links families to existing services and a continually updated inventory of community-based programs and services (Table 3). Such models can likely be extended to the identification and referral of family psychosocial issues. Currently, 47 states maintain toll-free telephone numbers (e.g., 2-1-1 Infoline) that enable families to be linked to available human service resources such as food banks, job training, Head Start, substance abuse counseling, and support groups. Nationally, over 16 million calls were received by 2-1-1 in 2009.64 In addition, state-run maternal and child health (MCH) toll-free telephone hotlines are also available to assist families with such issues as health insurance, parenting and child rearing topics, and children with mental health needs.65 Pediatric medical homes should become familiar with existing community resource hotlines.

Table 3.

Key Components of the Connecticut Help Me Grow (HMG) model

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Child Development Infoline (CDI) |

|

| 2. Inventory of community-based programs |

|

| 3. Provider training |

|

| 4. Data collection |

|

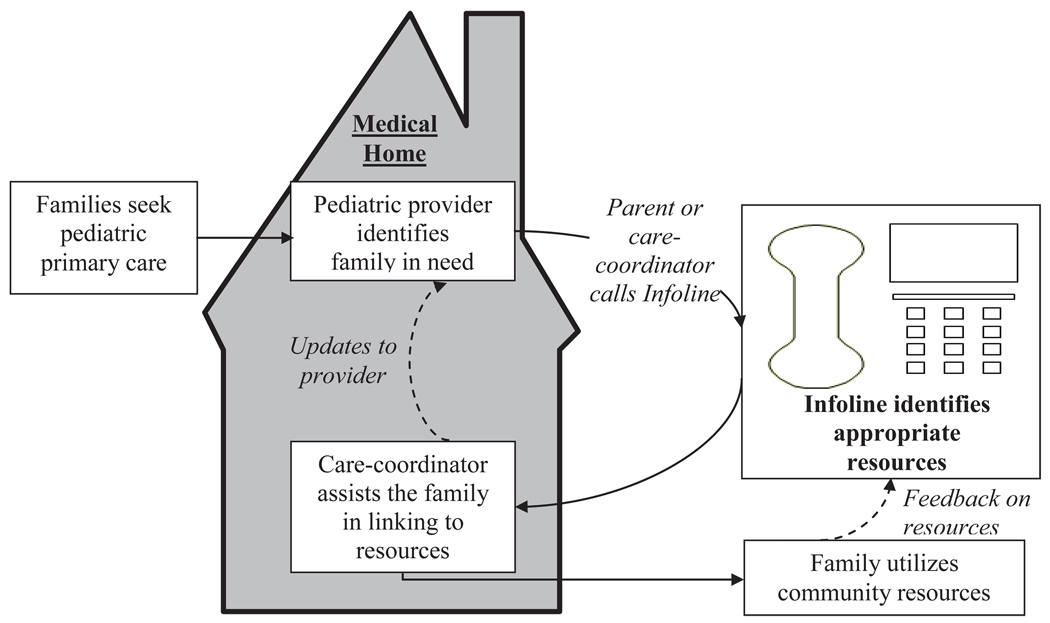

An integrated system of care could, for example, have pediatric providers identify families with psychosocial problems and refer them to a toll-free Infoline. Parents or care coordinators within the medical home could initiate the telephone call. Infoline personnel would provide contact information on available community resources. The care coordinator would help families access resources and update providers on families’ use of services. Feedback on the specific community resource’s ability to effectively address the family’s needs would inform the maintenance and updating of the Infoline resource inventory (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Integrated Care Model for Addressing Families’ Psychosocial Needs

The development of an integrated system for care coordination will require thoughtful responses to a variety of important issues. For example, how is the quality of services ensured? Will the system be prepared to manage large volumes of referrals? Cross-sector collaboration and partnerships are critical to ensure families’ access to a comprehensive array of programs and services.

IMPLICATIONS

Implementing family psychosocial surveillance and screening into pediatric primary care has implications for education, research, and public policy.

Education

Educating pediatricians on family psychosocial surveillance and screening should occur across the medical education continuum. Training curriculum should target providers’ knowledge of the impact of family psychosocial issues on child health and development, surveillance and screening skills, and awareness of available community resources.

Increasing providers’ knowledge should begin in medical school and continue during residency training. Exposure to community resources may be integrated within pediatric training. Many residency programs have advocacy rotations that offer this type of experience.66–68 This allows future pediatricians to gain a better understanding of how community services operate and the procedures (and paperwork) required of parents to access resources. Educating providers in practice about the social determinants of health and available community resources is an important priority for continuing medical education.

Educational initiatives aimed at increasing providers’ knowledge are necessary but insufficient to ensure practice change. Pediatric residents need “hands-on” training in family psychosocial surveillance and screening. This could be incorporated within mandatory child development rotations and practiced in primary care rotations. Residents typically provide care to low-income children in continuity clinic,69 thereby providing a robust opportunity to practice surveillance and screening and making referrals for an at-risk population. Reviewing quality measurement data on the identification of needs, referrals, utilization of resources, and correlation with child outcomes will allow providers to assess the impact of these endeavors.

Research

Research is needed to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of family psychosocial surveillance and screening within the medical home. Screening tools that broadly assess multiple family psychosocial issues need to be further developed. Different screening delivery systems (e.g., kiosks, internet-based, telephone, etc.) should also be evaluated in diverse patient populations. Prospective, longitudinal cohort studies and randomized controlled trials should evaluate the impact of surveillance and screening on short- and long-term child health and developmental outcomes. Finally, research grounded in diffusion of innovation theory will be important to identify key attributes for the dissemination into practice of novel surveillance/screening models.70,71

Qualitative and quantitative studies should evaluate strategies to overcome barriers to accessing community resources.72 We found that only one-third of urban families with identified basic needs such as food and childcare accessed community resources.73 Similarly, evaluation of the Help Me Grow model found that only 43% of referred children at risk for developmental delay successfully accessed services.63

The requirement for quality improvement projects by the American Board of Pediatrics for maintenance of certification, as well as such activities as The National Committee for Quality Assurance Patient-Centered Medical Home recognition program,74,75 may create incentives to evaluate efforts that incorporate family psychosocial surveillance and screening into routine pediatric practice. Advances in health information technology will enhance data collection capabilities and better enable the monitoring of quality indicators.

Public Policy

Incorporating family psychosocial surveillance and screening into the medical home and creating linkages to community resources has important public policy implications. Family psychosocial surveillance and screening and care coordination activities must be a valued and therefore, reimbursed component of pediatric primary care. Policies that enable and encourage cross-sector (and inter-agency) collaboration and partnerships are critical to ensure families’ access to a comprehensive array of programs and services. In Connecticut, Help Me Grow is a partnership among five state agencies, demonstrating the feasibility and benefits of this type of integrated model.62 Developing and implementing an integrated model of care will require strong leadership and advocacy from pediatric and community leaders and organizations both at the state and national levels.

CONCLUSIONS

As the early identification of developmental disorders is crucial to the well-being of children, so is early detection and intervention for family psychosocial issues. The core principles of surveillance and screening can be readily applied to the detection and referral of psychosocial issues by child health providers within the medical home. Integrating family psychosocial surveillance and screening into well-child care services requires changes in professional training, provider practice, and public policy. We believe that the potential of psychosocial surveillance and screening to enhance the effectiveness of child health supervision services to promote children’s optimal development justifies efforts to promote such changes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was begun while Arvin Garg was at the Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center. Arvin Garg was supported by Award Numbers K99HD056160 and R00HD056160 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development or the National Institutes of Health. We would like to thank Howard Bauchner MD, Kathi Kemper, MD, MPH, Ellen Perrin, MD, Ed Schor, MD, Chris Sheldrick, PhD and the two anonymous reviewers for their feedback and comments on the manuscript draft.

Abbreviations

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

There are no conflicts of interest for any of the authors above.

References

- 1.Kemper KJ, Kelleher KJ. Rationale for family psychosocial screening. Amb Child Health. 1996;1:311–324. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pati S, Hashim K, Brown B, Fiks A, Forrest CB. [Accessed December 20, 2010];Early childhood predictors of early school literature:a selective review of the literature. Available at: http://www.childtrends.org/...//Child_Trends-2009_05_26_FR_EarlySchoolSuccess.pdf.

- 3.Kemper KJ, Kelleher KJ. Family psychosocial screening: instruments and techniques. Amb Child Health. 1996;1:325–339. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarter RE, Kabene M, Escallier EA, Laird SB, Jacob T. Temperament deviation and risk for alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1990;14:380–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1990.tb00490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill SY, Locke J, Lowers L, Connolly J. Psychopathology and achievement in children at high risk for developing alcoholism. J AM Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:883–891. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199907000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolbo JR, Blakely EH, Engleman D. Children who witness domestic violence:a review of empirical literature. J Interpers Violence. 1996:281–293. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bair-Merritt MH, Blackstone M, Feudtner C. Physical health outcomes of childhood exposure to intimate partner violence: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e278–e290. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA. Food insufficiency and American school-aged children's cognitive, academic, and psychosocial development. Pediatrics. 2001;108:44–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA, Briefel RR. Food insufficiency, family income, and health in US preschool and school-aged children. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:781–786. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinreb L, Wehler C, Perloff J, et al. Hunger: its impact on children's health and mental health. Pediatrics. 2002;110:e41. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.4.e41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casey PH, Szeto KL, Robbins JM, et al. Child health-related quality of life and household food security. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:51–56. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood D, Halfon N, Scarlata D, Newacheck P, Nessim S. Impact of family relocation on children's growth, development, school function, and behavior. JAMA. 1993;270:1334–1338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood DL, Valdez RB, Hayashi T, Shen A. Health of homeless children and housed, poor children. Pediatrics. 1990;86:858–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shonkoff JP, Phillips DA, editors. From Neurons to Neighborhoods. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sameroff AJ, Seifer R, Barocas R, Zax M, Greenspan S. Intelligence quotient scores of 4-year-old children: social-environmental risk factors. Pediatrics. 1987;79:343–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halfon N, Hochstein M. Life course health development: an integrated framework for developing health, policy, and research. Milbank Q. 2002;80:433–479. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00019. iii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. [Accessed November 2, 2010];What is a family-centered medical home? Available at: http://www.medicalhomeinfo.org.

- 18.Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM. Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. 3rd edition. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008. Bright Futures. [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on the Family. Family pediatrics: report of the task force on the family. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1541–1571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. The new morbidity revisited: a renewed commitment to the psychosocial aspects of pediatric care. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1227–1230. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.5.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Community Health Services. The pediatrician's role in community pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1092–1094. [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Academy of Pediatrics, Medical Home Initiatives for Children with Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. The medical home. Pediatrics. 2002;110:184–186. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kemper KJ, Osborn LM, Hansen DF, Pascoe JM. Family psychosocial screening: should we focus on high-risk settings? J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1994;15:336–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kogan MD, Schuster MA, Yu SM, et al. Routine assessment of family and community health risks: parent views and what they receive. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1934–1943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garg A, Butz AM, Dworkin PH, Lewis RA, Serwint JR. Screening for basic social needs at a medical home for low-income children. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2009;48:32–36. doi: 10.1177/0009922808320602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hochstein M, Sareen H, Olson L, O'Connor K, Inkelas M, Halfon N. A comparison of barriers to the provision of developmental assessments and psychosocial screenings during pediatric health supervision. Pediatr Res. 2001:49. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olson AL, Kemper KJ, Kelleher KJ, Hammond CS, Zuckerman BS, Dietrich AJ. Primary care pediatricians' roles and perceived responsibilities in the identification and management of maternal depression. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1169–1176. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perez-Stable EJ, Juarez-Reyes M, Kaplan CP, Fuentes-Afflick E, Gildengorin V, Millstein SG. Counseling smoking parents of young children: comparison of pediatricians and family physicians. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:25–31. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frankowski BL, Weaver SO, Secker-Walker RH. Advising parents to stop smoking: pediatricians' and parents' attitudes. Pediatrics. 1993;91:296–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wall MA, Severson HH, Andrews JA, Lichtenstein E, Zoref L. Pediatric office-based smoking intervention: impact on maternal smoking and relapse. Pediatrics. 1995;96:622–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winickoff JP, Buckley VJ, Palfrey JS, Perrin JM, Rigotti NA. Intervention with parental smokers in an outpatient pediatric clinic using counseling and nicotine replacement. Pediatrics. 2003;112:1127–1133. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Curry SJ, Ludman EJ, Graham E, Stout J, Grothaus L, Lozano P. Pediatric-based smoking cessation intervention for low-income women: a randomized trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:295–302. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siegel RM, Hill TD, Henderson VA, Ernst HM, Boat BW. Screening for domestic violence in the community pediatric setting. Pediatrics. 1999;104:874–877. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.4.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holtrop TG, Fischer H, Gray SM, Barry K, Bryant T, Du W. Screening for domestic violence in a general pediatric clinic: be prepared! Pediatrics. 2004;114:1253–1257. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1071-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parkinson GW, Adams RC, Emerling FG. Maternal domestic violence screening in an office-based pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2001;108:e43. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kemper KJ, Babonis TR. Screening for maternal depression in pediatric clinics. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146:876–878. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1992.02160190108031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olson AL, Dietrich AJ, Prazar G, et al. Two approaches to maternal depression screening during well child visits. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26:169–176. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200506000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olson AL, Dietrich AJ, Prazar G, Hurley J. Brief maternal depression screening at well-child visits. Pediatrics. 2006;118:207–216. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Lane W, et al. Screening for depression in an urban pediatric primary care clinic. Pediatrics. 2007;119:435–443. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mishina H, Takayama JI. Screening for maternal depression in primary care pediatrics. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21:789–793. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328331e798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.AAP Policy Statement. Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: an algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics. 2006;118:405–420. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dworkin PH. British and American recommendations for developmental monitoring: the role of surveillance. Pediatrics. 1989;84:1000–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kenyon C, Sandel M, Silverstein M, Shakir A, Zuckerman B. Revisiting the social history for child health. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e734–e738. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duncan PM, Garcia AC, Frankowski BL, Carey PA, Kallock EA, Dixon RD, et al. Inspiring healthy adolescent choices: a rationale for and guide to strength promotion in primary care. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41:525–535. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Minkovitz CS, O'Connor KG, Grason H, et al. Pediatricians' involvement in community child health from 1989 to 2004. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:658–664. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.7.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kemper KJ. Self-administered questionnaire for structured psychosocial screening in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 1992;89:433–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perrin EC. Ethical questions about screening. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1998;19:350–352. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199810000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garg A, Butz AM, Dworkin PH, Lewis RA, Thompson RE, Serwint JR. Improving the management of family psychosocial problems at low-income children's well-child care visits: the WE CARE project. Pediatrics. 2007;120:547–558. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Honigfeld L, Mckay K. Barriers to enhancing practice-based developmental services. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27:S30–S33. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200602001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schor EL. Rethinking well-child care. Pediatrics. 2004;114:210–216. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fleeger E, Lieu TA, Wise PH, Nackashi J. Families' health-related social problems and missed referral opportunities. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1332–e1341. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.CHADIS: Child Health & Development Interactive System. [Accessed May 10, 2010]; Available at: http://www.chadis.com.

- 53.Sheldrick RC, Perrin EC. Surveillance of children's behavior and development: practical solutions for primary care. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009;30:151–153. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31819f1bfb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaye N, May J, Abrams M. State policy options to improve delivery of child development services: strategies from the eight ABCD states. National Academy for State Health Policy and The Commonwealth Fund. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 55.American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal and postpartum depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1032–1039. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adams K, Corrigan JM. Priority Areas for National Action: Transforming Health Care Quality. Washington DC: Institute of Medicine; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Antonelli R, McAllister JW, Popp J. Making care coordination a critical component of the pediatric health system: a multidisciplinary framework. The Commonwealth Fund. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mckay K, Shannon A, Vater S, Dworkin PH. ChildServ: lessons learned from the design and implementation of a community-based developmental surveillance program. Infants Young Child. 2006;19:371–377. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Radecki L, Olson LM, Frintner MP, Tanner JL, Stein MT. What do families want from well-child care? Including parents in the rethinking discussion. Pediatrics. 2009;124:858–865. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Silow-Carroll S, Hagelow G. Systems of care coordination for children: lessons learned across state models. The Commonwealth Fund. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 61.McCarthy D, Mueller K. Community care of North Carolina: building community systems of care through state and local partnerships. The Commonwealth Fund. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dworkin PH. Historical overview: from ChildServ to Help Me Grow. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27:S5–S7. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200602001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dworkin PH. Promoting development through child health services. Introduction to the Help Me Grow roundtable. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27:S2–S4. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200602001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. [Accessed December 23, 2010]; 211. Available at: http://www.211us.org. 211.

- 65.Booth M, Brown T, Richmond-Crum M. Dialing for help: state telephone hotlines as vital resources for parents of young children. The Commonwealth Fund. 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roth EJ, Barreto P, Sherritt L, Palfrey JS, Risko W, Knight JR. A new, experiential curriculum in child advocacy for pediatric residents. Ambul Pediatr. 2004;4:418–423. doi: 10.1367/A04-010R1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kaczorowski J, Aligne CA, Halterman JS, Allan MJ, Aten MJ, Shipley LJ. A block rotation in community health and child advocacy: improved competency of pediatric residency graduates. Ambul Pediatr. 2004;4:283–288. doi: 10.1367/A03-140R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chamberlain LJ, Sanders LM, Takayama JI. Child advocacy training: curriculum outcomes and resident satisfaction. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:842–847. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.9.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weitzman M, Byrd RS, Auinger P. Children in big cities in the United States: health and related needs and services. Ambul Child Health. 1996;1:347–359. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bradley EH, Webster TR, Baker D. Translating research into practice: speeding the adoption of innovative health care programs. The Commonwealth Fund. 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dearing JW. Applying diffusion of innovation theory to intervention development. Res Soc Work Pract. 2009;19:503–518. doi: 10.1177/1049731509335569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Silverstein M, Lamberto J, DePeau K, Grossman DC. "You get what you get": unexpected findings about low-income parents' negative experiences with community resources. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e1141–e1148. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Garg A, Sarkar S, Marino M, Onie R, Solomon BS. Linking urban families to community resources in the context of pediatric primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79:251–254. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.American Board of Pediatrics. [Accessed February 24, 2011]; Available at: http://www.abp.org.

- 75.NCQA. [Accessed February 24, 2011]; Available at: http://www.ncqa.org.

- 76.Cook JT, Frank DA, Berkowitz C, et al. Food insecurity is associated with adverse health outcomes among human infants and toddlers. J Nutr. 2004;134:1432–1438. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.6.##. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Skalicky A, Meyers AF, Adams WG, Yang Z, Cook JT, Frank DA. Child food insecurity and iron deficiency anemia in low-income infants and toddlers in the United States. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10:177–185. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nord M, Andrews M, Carlson S. Household Food Security in the United States 2004. Washington, DC: US Dept of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nord M. [Accessed December 1, 2010];A 30-day food security scale for current population survey food security supplement data. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/efan02015/efan02015.pdf.

- 80.Kleinman RE, Murphy JM, Wieneke KM, Desmond MS, Schiff A, Gapinski JA. Use of a single-question screening tool to detect hunger in families attending a neighborhood health center. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7:278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hager ER, Quigg AM, Black MM, et al. Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e26–e32. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Roth L, Fox ER. Children of homeless families: health status and access to health care. J Community Health. 1990;15:275–284. doi: 10.1007/BF01350293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Weinreb L, Goldberg R, Bassuk E, Perloff J. Determinants of health and service use patterns in homeless and low-income housed children. Pediatrics. 1998;102:554–562. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.3.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.U.S. Census Bureau. The American Housing Survey. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kitzmann KM, Gaylord NK, Holt AR, Kenny ED. Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:339–352. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wolfe DA, Crooks CV, Lee V, McIntyre-Smith A, Jaffe PG. The effects of children's exposure to domestic violence: A meta-analysis and critique. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2003;6:171–187. doi: 10.1023/a:1024910416164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wasson JH, Jette AM, Anderson J, Johnson DJ, Nelson EC, Kilo CM. Routine, single-item screening to identify abusive relationships in women. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:1017–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Straus MA. Manual for the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) and test forms for the revised conflict tactics scale (CTS2) Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire Family Research Laboratory; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sherin KM, Sinacore JM, Li XQ, Zitter RE, Shakil A. HITS: a short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Fam Med. 1998;30:508–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Feldhaus KM, Koziol-McLain J, Amsbury HL, Norton IM, Lowenstein SR, Abbott JT. Accuracy of 3 brief screening questions for detecting partner violence in the emergency department. JAMA. 1997;277:1357–1361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Brown JB, Lent B, Brett PJ, Sas G, Pederson LL. Development of the Woman Abuse Screening Tool for use in family practice. Fam Med. 1996;28:422–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Brown JB, Lent B, Schmidt G, Sas G. Application of the Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) and WAST-short in the family practice setting. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:896–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rabin RF, Jennings JM, Campbell JC, Bair-Merritt MH. Intimate partner violence screening tools: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:439–445. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zimmer KP, Minkovitz CS. Maternal depression: an old problem that merits increased recognition by child healthcare practitioners. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2003;15:636–640. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200312000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Knesevich JW, Biggs JT, Clayton PJ, Ziegler VE. Validity of the Hamilton Rating Scale for depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1977;131:49–52. doi: 10.1192/bjp.131.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rush AJ, Jr, First MB, Blacker D. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. 2nd edition. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dubowitz H, Black MM, Kerr MA, et al. Type and timing of mothers' victimization: effects on mothers and children. Pediatrics. 2001;107:728–735. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Korfmacher J. The Kempe family stress inventory: a review. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2000;24:129–140. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.DiFranza JR, Lew RA. Morbidity and mortality in children associated with the use of tobacco products by other people. Pediatrics. 1996;97:560–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Environmental Health. Environmental tobacco smoke: a hazard to children. Pediatrics. 1997;99:639–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.National Cancer Institute. Health Effects of Exposure to Environmental Tobacco Smoke: The Report of the California Environmental Protection Agency. Bethesda, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor TF, et al. Validation of the Alcohol, Smoking And Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) Addiction. 2008;103:1039–1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fagerstrom KO, Schneider NG. Measuring nicotine dependence: a review of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. J Behav Med. 1989;12:159–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00846549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Children of Alcoholics Foundation. Childrens of Alcoholics in the Medical System: Hidden problems, Hidden Costs. New York, NY: Children of Alcoholics Foundation; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kelleher K, Chaffin M, Hollenberg J, Fischer E. Alcohol and drug disorders among physically abusive and neglectful parents in a community-based sample. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1586–1590. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.10.1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Johnson JL, Leff M. Children of substance abusers: overview of research findings. Pediatrics. 1999;103:1085–1099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bohn MJ, Babor TF, Kranzler HR. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation of a screening instrument for use in medical settings. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:423–432. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ewing JA. Screening for alcoholism using CAGE. Cut down, Annoyed, Guilty, Eye opener. JAMA. 1998;280:1904–1905. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.22.1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav. 1982;7:363–371. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Selzer ML. The Michigan alcoholism screening test: the quest for a new diagnostic instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1971;127:1653–1658. doi: 10.1176/ajp.127.12.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Chan AW, Pristach EA, Welte JW, Russell M. Use of the TWEAK test in screening for alcoholism/heavy drinking in three populations. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:1188–1192. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb05226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]