Abstract

Introduction

The recent history of integrated health care in Sweden is explored in this article, focusing on the first decade of the 2000s. In addition, there are some reflections about successes and setbacks in this development and challenges for the next decade.

Description of policy and practice

The first efforts to integrate health care in Sweden appeared in the beginning of the 1990s. The focus was on integration of intra-organisational processes, aiming at a more cost-effective health care provision. Partly as a reaction to the increasing economism at that time, there was also a growing interest in quality improvement. Out of this work emerged the ‘chains of care’, integrating all health care providers involved in the care of specific patient groups. During the 2000s, many county councils have also introduced inter-organisational systems of ‘local health care’. There has also been increasing collaboration between health professionals and other professional groups in different health and welfare services.

Discussion and conclusion

Local health care meant that the chains of care and other forms of integration and collaboration became embedded in a more integrative context. At the same time, however, policy makers have promoted free patient choice in primary health care and also mergers of hospitals and clinical departments. These policies tend to fragment the provision of health care and have an adverse effect on the development of integrated care. As a counterbalance, more efforts should be put into evaluation of integrated health care, in order to replace political convictions with evidence concerning the benefits of such health care provision.

Keywords: Sweden, integrated health care, chains of care, local health care

Introduction

In Sweden as in many other countries there has been an increasing differentiation of roles and responsibilities within the health system, which has generated a corresponding need for integration of health services [1]. Thus, integration has become a more and more important task for the Swedish health authorities. By the end of the past millennium, however, the health authorities were increasingly drawing on external inspiration in their efforts to improve the performance of the system. Inspired by success stories from the private sector [2], the focus of organisational development shifted from a division of functions to an integration of multifunctional activities [3]. This new focus generated two main approaches for the integration of health care: improvement of intra-organisational processes and design of inter-organisational structures [4]. Before describing this development in more detail, it is necessary with a short background.

During the 1960s there was an ambition in Sweden to create an integrated system of health care on the regional level of the society. The responsibilities for primary health care and psychiatric care were decentralised from the national government to the county councils, who were already responsible for the general hospitals. In 1967, the county councils were responsible for all the different branches of health care. They were also quite independent of the national government, since most of their activities were financed through county taxes. Thus, since the 1960s, the political as well as the financial power in the Swedish health system has been resting on the regional level of the society [5].

In the beginning of the 1990s, this decentralised health system was further decentralised when the responsibility for care of the elderly was transferred from the county councils to the municipalities. This was a national reform in order to improve the integration between the health services of the county councils and the social services of the municipalities, and also to improve the collaboration between health professionals and social workers [6]. For the same reasons, there was another national reform a few years later, where the responsibility for care of the functionally disabled and long-term psychiatric care was also transferred from the county councils to the municipalities [7].1

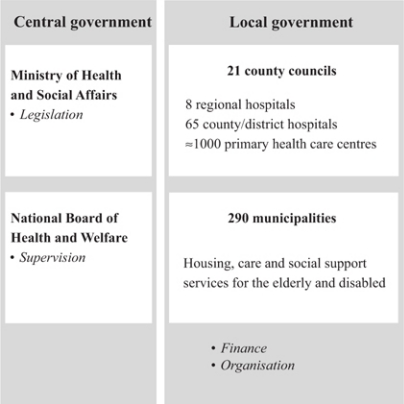

After these reforms in the 1990s, the main stakeholders of the Swedish health system and their principal responsibilities are as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Main stakeholders of the Swedish health care system and their principal duties.

Although health care in Sweden is financed mainly from public sources, there has been a growing private sector involvement in the health system from the beginning of the 1990s. There have been an increasing number of private providers, mainly in primary health care and care of the elderly, who have been contracted through competitive procurement and financed by the county councils and the municipalities. This process of privatisation has increased the differentiation of the Swedish health system and today private providers account for almost 10% of the total health care expenditures [9].

The increasing differentiation, as a result of the increasing number of private providers, has run contrary to the integration of health and social services in the county councils and municipalities. So has also the market oriented models with purchaser–provider split that were introduced in about half of the county councils in the beginning of the 1990s. Both of these developments were inspired by the ideas of New Public Management, which meant an application of management principles from the private sector in the public sector [10, 11]. There were political as well as economic considerations behind these ideas, and they were promoting competition rather than collaboration in health care [12].

By the end of the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s most county councils have abandoned their market oriented models, since they were not delivering the efficiency that had been expected. In addition, there were also high transaction costs connected with these models [13]. Partly as a reaction to the ‘economism’ of the market models, many county councils have instead introduced different models of quality improvement and quality management in health care. Since most of these models are process orientated, they have also brought a renewed interest in integration and collaboration [5].

This article will further explore the recent history of integrated health care in Sweden. Tracing the origins back to the 1990s, the focus will be on the development of integration and collaboration in the Swedish health system during the first decade of the 2000s. In addition to the historical account, there will be some analytical reflections in connection with the different stages of the development. There will also be an analysis of the successes and setbacks with the wisdom of hindsight. Finally, some of the challenges of integrated health care for the next decade will be discussed.

The heritage from the 1990s

The first efforts to integrate health care in Sweden were inspired by the so-called ‘producer model’ from the manufacturing industry [14]. According to this model, the core processes within an organisation must be integrated in order to create predetermined outcomes in a cost-effective way. Furthermore, such processes should be repetitive, consist of sequential activities, and have a distinct start and end.

Many well-known methods of process development have been derived from the producer model, like for instance ‘Business Process Re-engineering’ [15] and ‘Business Process Improvement’ [16]. The successful use of these methods in the private sector has inspired health care organisations in Sweden to integrate their processes in the same way. In the beginning of the 1990s, methods of process development were used in settings similar to manufacturing, i.e., when health care activities were repetitive, sequential and had predetermined outcomes. Elective surgery was one of the areas where Swedish health care was successful in developing integrated intra-organisational processes [4].

By the end of the 1990s, when more and more county councils had abandoned their market oriented models, there was an increasing interest in the quality of health care. Different models of quality improvement were introduced, for example the Swedish model called QUL, an acronym for quality, development and management [17]. These models were derived from the producer model. At the same time, however, there was a growing awareness that all health care did not have conditions equal to the manufacturing industry. Instead, it was pointed out that health care provision is based on a complex mixture of patient needs, which require contributions from many different departments and organisations. This means an inter-organisational rather than intra-organisational context.

These considerations were important also for the development of ‘chains of care’ [18]. This is a Swedish concept of integration and collaboration in health care, which includes all the services provided for a specific group of patients within a defined geographical area. Chains of care are inter-organisational networks based on clinical guidelines, i.e., agreements on the content and distribution of the clinical work between different health care providers and professionals. Most chains of care can be described as co-ordinated networks, where financial and clinical responsibilities of the parties involved remain separated. Furthermore, binding contracts, regulating the activities performed, are usually not in place [4].

The chain of care concept has a clear patient focus, sometimes also expressed as a ‘customer orientation’ [19]. Because of this orientation, the concept was considered to be part of the New Public Management in the 1990s, although chains of care were introduced already in the 1980s. Within the framework of the purchaser–provider split, there were also some experiments of commissioning a whole chain of care. The aim was to create incentives for providers to develop cost-effective care through the whole chain. In spite of these experiments, however, the chains of care have remained a concept for improving the quality rather than the cost-effectiveness of health care [20].

The entrance of the new millennium

The development of integrated health care in Sweden has continued in the new millennium. In the beginning of the 2000s, the chains of care were well established in many county councils. Some of them had quite an impressive record with 25 or more chains of care, most of them focusing on chronic diseases [18]. At the same time, however, a majority of county councils were dissatisfied with their development of integrated health care, because of difficulties to implement sustainable solutions in a predominantly non-integrative context [20] and negative reactions from health care professionals to top-down development approaches [21].

The development of integrated health care has not been limited to chains of care. During the 2000s, many Swedish county councils have also restructured their health services and introduced a system of ‘local health care’, which can be described as an upgraded family- and community-oriented primary health care within a defined local area, supported by flexible hospital services. The ambition has been to create an integrated provision of health care that fits the needs of a local population, which means that the content and form of local health care may differ from one area to another [22]. According to the National Board of Health and Welfare, two out of three county councils including the largest ones have implemented local health care, which means that 80% of the Swedish population are covered by this form of integrated care [23].

Because of different local needs and circumstances, there is no single model of local health care to be applied everywhere [22]. In most county councils, however, the introduction of local health care has not involved any large-scale organisational changes. It has rather been a question of combining existing organisations, resources and competences to secure adequate responses to the most frequent needs of the local population. This means quite a loose integration, which has been achieved mainly by chains of care [23]. Thus, there seems to be a mutual relationship between local health care and chains of care. Local health care needs chains of care as integrating mechanisms and the chains of care are strengthened by the integrative context of local health care [20].

The implementation of local health care has been important also for the integration of health and social services. This is the case particularly in care of the elderly and long-term psychiatric care, which were also the targets of the national reform in the 1990s. Local health care has facilitated collaboration between health professionals and social workers, for example in ‘dementia teams’ [24], ‘multidisciplinary home care teams’ [25], different forms of ‘case management’ [26] and ‘rehabilitation teams’ [27].

These forms of collaboration have not been restricted to local health care. Health professionals have collaborated with social workers also in other contexts, for example in teams for ‘assertive community treatment’ of mental illness [28], in centres for treatment and prevention of addiction and dependency [29], and in support to vulnerable children and young people [30]. Another area of multiprofessional collaboration has been in health care for refugees [31]. There have also been experiments with a common organisation for health and social service in one municipality [32] and a consortium for mental health and social care in another municipality [33].

The most extensive experiments in inter-organisational integration have been in the field of vocational rehabilitation, where health professionals have collaborated with social workers and officials from the social insurance administration and the national employment service [34]. There have also been EU projects on collaboration in vocational rehabilitation between the same organisations and professional groups [35]. The positive outcomes of these experiments and projects have resulted in a legislation, which makes it possible for county councils and municipalities to form ‘local associations’ for financial co-ordination together with the local offices of the social insurance administration and the national employment service [36]. Today there are more than 80 associations of this kind in Sweden [37].

The financial co-ordination means that resources from the different organisations are pooled into a common budget for the local association. This budget may be used for different rehabilitation projects, which are managed by the association. These projects are usually aimed at individuals with multiple problems that require collaboration between professionals from the different organisations involved [38].

With the wisdom of hindsight

When the responsibilities for care of the elderly and long-term psychiatric care were transferred from the county councils to the municipalities, there was an incentive to allocate patients to the most cost-effective care possible. As a result, the number of hospital beds in Sweden was reduced by 45%, during the 1990s, while most other European countries had a reduction by 10–20% during the same period of time [39]. Thus, the integration of health and social services may have improved cost-effectiveness, but it also created new problems related to a lack of physicians in municipal nursing homes and parallel organisations for home health care in the county councils and the municipalities [25].

The integration of health and social services in the 1990s was problematic also for other reasons. There were many ‘territorial’ conflicts between the different organisations and professions involved [8]. However, with the introduction of local health care, the provision of integrated care for the elderly and the mentally ill has been improved. Gaps between the different services can be bridged, and the quality of care and rehabilitation surely benefit from the multiprofessional collaboration within the framework of local health care [40].

Concerning the chains of care, a national survey has shown that seven out of 10 county councils in Sweden were disappointed with their development work [18]. As mentioned before, it seems that the chains of care had been implemented mainly through a top-down approach, which was not appropriate in an environment dominated by strong professional groups. In such an environment, developments initiated from the top of the organisation are often resisted. If the development of chains of care had been initiated from below by dedicated professionals, it would probably have been more successful [21].

There have also been other reasons for resistance to the development of integrated health care. For instance, the general practitioners have not supported the decentralisation of responsibility for the care of the elderly to the municipalities, since it has threatened their position as managers of the nursing homes [41]. The implementation of local health care has aroused similar reactions among the general practitioners, who have thought there is a risk that primary health care will disappear or become more anonymous [42].

In vocational rehabilitation, the financial coordination between the different organisations involved has eliminated many obstacles to integration and collaboration. One of the main obstacles has been the fear of costs being transferred between the organisations involved [43]. Moreover, it seems that the local associations of financial co-ordination have improved the management and continuity of vocational rehabilitation [44]. On the other hand, many of the rehabilitation activities of the local associations are temporary and regarded as projects, which means that they are separated from the different organisations involved. The integration is limited to these projects and not really influencing ordinary work [45].

According to organisation theory, the level of integration in health care should be related to the degree of differentiation of services. A high degree of differentiation requires a high degree of integration [46]. Therefore, the degree of integration varies between different organisations and services, depending on their need for integration. The degree of integration is also depending on the possibility to attain ‘collaborative advantage’ [47]. Organisational researchers have pointed out that it is important for stakeholders to discover and recognise the possible advantages of collaboration. Unless there is potential for such advantages, collaboration should be avoided [48].

The development of integration may even be destructive when collaborative advantages are concealed or lacking, since professionals as well as managers tend to defend their territories when these are believed to be threatened [38]. Such a shift of focus, from joint activities to protection of boundaries, may have very negative effects. In Sweden, there have been many examples, like resource battles between health care providers [49], threats against the position of the physicians [42], and unwillingness to collaborate in general [6].

Although there have been many setbacks in the development of integrated health care, it seems that more favourable conditions have emerged during the past decade. As described before, there is a ‘mutualistic’ relationship between chains of care and local health care [20]. Chains of care have become the building blocks of local health care, and they have also benefited from being embedded in such an integrative context. This context has also been favourable for other forms of integration and collaboration between health and social services. In addition, integration in vocational rehabilitation has been facilitated by new legislation encouraging county councils, municipalities and state agencies to collaborate and to create local associations of financial co-ordination [36].

Challenges for the next decade

Despite the fact that integrated health care has been high on the political agendas during the last two decades, counteracting policies have been, and are still, promoted. The increasing privatisation and the period of purchaser–provider split have been mentioned before. Both of these developments were based on political as well as economic considerations. Lately, a new system of free choice for patients in primary health care has been proposed by a parliamentary committee and is expected to be introduced in all the county councils [50]. According to the proposal, the free patient choice will generate a capitation payment to the chosen primary health care centre. This system is based mainly on political convictions. Policy makers believe that, as a result of competition between health centres, strong providers will survive while unprofitable ones will be eliminated [22].

In order to implement the new system different models of patient choice have been developed. In some county councils the patients can choose among comprehensive local health care arrangements, whereas in other county councils they register for a specific general practitioner [51]. There is a great challenge for the health authorities to simultaneously manage both competition and collaboration, although it is easier when patients choose among networks of integrated health care and not among individual health care providers. Models of the latter kind tend to fragment the provision of health services.

Although inter-organisational integration been promoted, developed and implemented during the last two decades, intra-organisational integration has still a strong foothold in Swedish health care. In recent years there have been a number of mergers of hospitals and creation of hospital groups under joint management. These mergers are aiming at large-scale production and motivated by economies of scale. They have also been strongly endorsed by policy makers. In spite of bad experiences, related to the size and complexity of the new hospital organisations, the mergers are spreading to more and more county councils [52]. As a result, the number of hospitals has been halved since the beginning of the 1990s. Today there are only 53 general hospitals in Sweden and many of them are multi-sited hospital groups. This restructuring of hospitals is proceeding in spite of the fact that the multi-sited hospitals have not been systematically evaluated, neither in Sweden nor internationally [53].

Regardless of this lack of evidence, the hospital mergers have been followed by proposals about a merger of the Swedish county councils. A parliamentary committee has proposed that the present 21 Swedish county councils should be merged into 6–8 more equally sized regional councils [54]. The committee apparently mistrusts the willingness and ability of the county councils to integrate their services and collaborate with each other. The confidence in mergers and large-scale solutions appears be widespread among the policy makers [52].

To conclude, it is clear that Swedish policy makers have been supporting the development of integrated health care during the last decade, but at the same time they have also been promoting contrary strategies implying a fragmentation of health services and mistrust in collaborative advantages. Even if consistency is not necessarily a political virtue, the contradictory policies could possibly be linked to the lack of evidence about the benefits of integrated health care [55]. In any case, more efforts should be placed on the evaluation of integrated health care, as well as the other developments described, in order to replace political convictions with evidence on the benefits of different forms of health care provision.

Reviewers

Marcus J. Hollander, PhD, President, Hollander Analytical Services Ltd, Victoria, BC, V8W 1H7, Canada

Henk Nies, PhD, CEO, Vilans, Netherlands Centre of Expertise for Long-term Care, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Mats Brommels, Professor, Department of Public Health, University of Helsinki, Finland

Footnotes

In order to avoid the conceptual confusion in the literature of integrated care, the concept of integration will be used in this article mainly in inter-organisational contexts, while collaboration will be used in inter-professional contexts. For a discussion of this terminology, see [8].

Contributor Information

Bengt Ahgren, Nordic School of Public Health, P.O. Box 12133, SE-402 42 Göteborg, Sweden.

Runo Axelsson, Nordic School of Public Health, P.O. Box 12133, SE-402 42 Göteborg, Sweden.

References

- 1.Kodner D, Spreeuwenberg C. Integrated care: meaning, logic, applications, and implications—a discussion paper. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2002 Nov 14;2 doi: 10.5334/ijic.67. Available from: http://www.ijic.org/. URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deming W. Out of the Crisis. Cambridge, MA: MIT Center for Advanced Engineering Study; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreasson S, Brommels M, Sarv H, editors. Det måste finnas ett annat sätt. [There must be another way]. Stockholm: Swedish Federation of County Councils; 1995. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahgren B. Creating Integrated Health Care. NHV-report 2007:2. Göteborg: Nordic School of Public Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Axelsson R. The organizational pendulum. Healthcare management in Sweden 1865–1998. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2000;28:47–53. doi: 10.1177/140349480002800109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adamiak G, Karlberg I. The situation in Sweden. In: van Raak A, Mur-Veeman I, Hardy B, Steenbergen M, Paulus A, editors. Integrated Care in Europe. Description and Comparison of Integrated Care in Six EU Countries. Maarssen: Elsevier Gezondheidszorg; 2003. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danermark B, Kullberg C. Samverkan—välfärdsstatens nya arbetsform. [Collaboration—the new working method of the welfare state]. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 1999. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Axelsson R, Bihari Axelsson S. Integration and collaboration in public health—a conceptual framework. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2006;21(1):75–88. doi: 10.1002/hpm.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Axelsson R, Wadensjö E. Pensions, health and long-term care. ASISP Annual National Report 2010: Sweden. Brussels: European Commission; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hood C. A public management for all seasons? Public Administration. 1991;69:3–19. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollitt C. Managerialism and the Public Services: The Anglo-American Experience. Oxford: Blackwell; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hallin B, Siverbo S. Styrning och organisering inom hälso- och sjukvården. [Management and organisation in health care]. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2003. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siverbo S. The purchaser–provider split in principle and practice: experiences from Sweden. Financial Accountability and Management. 2004;20(4):401–20. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anthony RN, Dearden J, Bedford NM. Management Control Systems. 6th edition. Homewood, Illinois: Irwin; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammer M, Champy J. Reengineering the corporation: a manifesto for a business revolution. London: Nicholas Brealey; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrington HJ. Business process improvement: the Breakthrough Strategy for Total Quality, Productivity and Competitiveness. US: McGraw-Hill; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swedish Federation of County Councils. Kriterier och anvisningar för Qvalitet Utveckling Ledarskap 2000/2001—ett instrument för verksamhetsutveckling. [Criteria and instructions of Quality Development and Management 2000/2001—A tool for activity development]. Stockholm: Landstingsförbundet; 2000. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahgren B. Chain of care development in Sweden: results of a national study. International Journal of Integrated Care. [serial online] 2003 October 7:3. [cited 2011 17 February]. Available from: http://www.ijic.org/. URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindberg K, Trägårdh B. Idén om vårdkedja möter lokal praxis. [The chain of care concept faces local practice]. Kommunal ekonomi och politik. 2001;5(2):51–68. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahgren B. Mutualism and antagonism within organisations of integrated health care. Journal of Health Organization and Management. 2010;24(2):396–411. doi: 10.1108/14777261011065002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahgren B, Axelsson R. Determinants of integrated health care development: chains of care in Sweden. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2007;2:145–57. doi: 10.1002/hpm.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahgren B. Competition and integration in Swedish health care. Health Policy. 2010;96(2):91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Board of Health and Welfare. Kartläggning av närsjukvård. [Survey of local health care]. Stockholm: National Board of Health and Welfare; 2003. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haraldsson U, Wånell SE. Demensteam: en nationell överblick. [Dementia team: a national overview]. Stockholm: Stockholm Gerontology Research Centre; 2009. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Board of Health and Welfare. Hemsjukvård i förändringe. [Home care in change]. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 2008. Nov, [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Board of Health and Welfare. Personligt ombud på klientens uppdrag—förhandlare och gränsöverskridare. [Personal representative by order of the client—negotiator and exceeder of limits]. Stockholm: National Board of Health and Welfare; 2005. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Board of Health and Welfare. Rehabilitering för hemmaboende äldre personer. [Rehabilitation of elderly persons living at home]. Stockholm: National Board of Health and Welfare; 2007. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malm U. Case management: evidensbaserad integrerad psykiatri. [Case management: evidence based integrated psychiatry]. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2002. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Board of Health and Welfare. Missbruks- och beroendevårdens öppenvård (ÖKARTen nationell kartläggning. [Outpatient care of addiction and dependency: a national survey]. Stockholm: National Board of Health and Welfare; 2008. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Board of Health and Welfare. Strategi för samverkan—kring barn och unga som far illa eller riskerar att fara illa. [Strategy for collaboration—about children and youngsters in trouble or who are risking getting into trouble]. Stockholm: National Board of Health and Welfare; 2007. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindencrona F, Ekblad S, Axelsson R. Modes of interaction and performance of human service networks. Public Management Review. 2009;11(2):191. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Øvretveit J, Hansson J, Brommels M. An integrated health and social care organisation in Sweden: Creation and structure of a unique public health and social system. Health Policy. 2010;97:113–21. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hansson J, Øvretveit J, Askerstam M, Gustafsson C, Brommels M. Coordination in networks for improved mental health service. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2010 Aug 25;10 doi: 10.5334/ijic.511. [cited 2011 17 February]. Available from: http://www.ijic.org/. URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wihlman U, Stålsby Lundborg C, Holmström I, Axelsson R. Organising vocational rehabilitation through interorganisational integration—a case study in Sweden. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2010 doi: 10.1002/hpm.1067. (in press). Available from: Wiley Online Library. DOI: 10.1002/hpm.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norman C, Axelsson R. Co-operation as a strategy for provision of welfare services a study of a rehabilitation project in Sweden. European Journal of Public Health. 2007;17(5):532–6. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.SFS 2003:1210. Lag om finansiell samordning av rehabiliteringsinsatser. [The act on financial co-ordination of rehabilitation measures between the social insurance office, the county labour boards, municipalities and county councils]. Stockholm: Svensk författningssamling; 2003. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Finsam. Översikt över samordningsförbunden 2010. [Overview of the associations for financial co-ordination 2010]. [webpage on the internet]. [cited 2011 17 February]. Available from: http://www.susam.se/finsam/oversikt_forbund. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bihari Axelsson S, Axelsson R. From territoriality to altruism in interprofessional collaboration and leadership. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2009;23(4):320–30. doi: 10.1080/13561820902921811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKee M. Reducing hospital beds. What are the lessons to be learned? Vol. 6. Copenhagen: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rom M. Närvård i Sverige 2005. [Local health care in Sweden 2005]. Stockholm: Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andersson G, Karlberg I. Integrated care for the elderly. The background and effects of the reform of Swedish care of the elderly. International Journal of Integrated Care. [serial online] 2000 November 1;1. [cited 2011 17 February]. Available from: http://www.ijic.org. URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anell A. Primärvård i förändring. [Primary health care in change]. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2005. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hultberg E, Lönnroth K, Allebeck P. Effects of a co-financed interdisciplinary collaboration model in primary health care on service utilisation among patients with musculoskeletal disorders. Work. 2007;28(3):239–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andersson J, Axelsson R, Bihari Axelsson S, Eriksson A, Åhgren B. Samverkan inom arbetslivsinriktad rehabilitering. En sammanställning av kunskap och erfarenheter inom området. [Collaboration in vocational rehabilitation. A review of knowledge and experiences in the area]. Stockholm: National Council for Financial Co-ordination; February 2010. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Löfström M. Inter-organizational collaboration projects in the public sector: a balance between integration and demarcation. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2010;25(2):136–55. doi: 10.1002/hpm.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lawrence PR, Lorsch JW. Organization and Environment. Managing Differentiation and Integration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huxham C, editor. Creating collaborative advantage. London: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huxham C, Vangen S. Managing to collaborate: the theory and practice of collaborative advantage. London: Routledge; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trädgårdh B, Lindberg K. Curing a meagre health care system by lean methods—translating chains of care in the Swedish health care sector. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2004;19:383–98. doi: 10.1002/hpm.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.SOU 2008:37. Vårdval i Sverige. [Choice of care in Sweden]. Stockholm: Ministry of Health and Social Affairs; 2009. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anell A. Vårdval i primärvården—modeller och utvecklingsbehov. [Choice of care in primary care—models and needs for development]. Lund: KEFU; 2008. [in Swedish] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ahgren B. Is it better to be big? The reconfiguration of 21st century hospitals: Responses to a hospital merger in Sweden. Health Policy. 2008;87:92–9. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Posnett J. The hospital of the future: is bigger better? Concentration in provision of secondary care. British Medical Journal. 1999;319:1063–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7216.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.SOU 2007:10. Hållbar samhällsorganisation med utvecklingskraft. [Sustainable organisation of society with development power]. Stockholm: Ministry of Finance; 2007. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nies H. A European Research Agenda on Integrated Care for Older People. Dublin: EHMA; 2004. [Google Scholar]