Abstract

Introduction

Québec’s rapidly growing elderly and chronically ill population represents a major challenge to its healthcare delivery system, attributable in part to the system’s focus on acute care and fragmented delivery.

Description of policy practice

Over the past few years, reforms have been implemented at the provincial policy level to integrate hospital-based, nursing home, homecare and social services in 95 catchment areas. Recent organizational changes in primary care have also resulted in the implementation of family medicine groups and network clinics. Several localized initiatives were also developed to improve integration of care for older persons or persons with chronic diseases.

Conclusion and discussion

Québec has a history of integration of health and social services at the structural level. Recent evaluations of the current reform show that the care provided by various institutions in the healthcare system is becoming better integrated. The Québec health care system nevertheless continues to face three important challenges in its management of chronic diseases: implementing the reorganization of primary care, successfully integrating primary and secondary care at the clinical level, and developing effective governance and change management.

Efforts should focus on strengthening primary care by implementing nurse practitioners, developing a shared information system, and achieving better collaboration between primary and secondary care.

Keywords: integrated care, health care system, chronic disease, health policy, Quebec/Canada

1. Introduction

Like other developed countries, Canada faces a rapidly growing elderly and chronically ill population that represents a major challenge to healthcare delivery systems. This is a challenge for Canada since its health care system is poorly-ranked among the developed countries with respect to indicators of performance in the care of chronic diseases [1–3]. This poor ranking is attributable to a system focused on acute care, fragmented delivery and deficiencies in patient centeredness, among other factors [1]. Adjusting healthcare delivery systems to improve care for people with chronic conditions is the primary focus of many reforms, as well as localized initiatives run in various Canadian provinces in order to improve service coordination and/or integration, reduce resource waste, fragmented care and patient dissatisfaction and improve cost-effectiveness [4].

Canada is a federation of 10 provinces and three territories. Provision of health care is a provincial and territorial responsibility, allowing considerable flexibility in health policy at the provincial and territorial level [5]. Consequently, rather than describing the situation in all Canadian provinces, it is more appropriate to provide an in-depth description of the situation in a specific province, hence this article will examine Québec.

The purpose of this article is first to describe the transformation currently underway and the results of recent initiatives in integrated health and social care, more specifically for people with multiple chronic diseases. A wide-ranging review of the scientific and grey literature (1998–2010) was conducted using different combinations of the following key words: chronic care model, chronic disease management, chronic disease model, elders, aged, hospital, acute care, barrier, incentive, disincentives, facilitators, and obstacles. Searches were conducted in Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, Psychinfo, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Scirus, Pubmed, Google scholar and Google. Specific web sites were also consulted, such as those of the Québec Ministry of Health and Social Services. Our focus is on the extent to which system-wide transformation and localized initiatives achieved the integration objective, and to identify barriers and facilitators to achieving such integration. In the last section, we suggest potential future clinical, organizational and research developments.

In this paper, the definition of integration is based on components of integration identified by Leutz [6], Nies and Berman [7] and Kodner and Spreeuwenberg [8]. Integration has been recently conceptualized in Québec, as ‘the process of combining social and health services in order to meet the needs of the frail elderly, through alignment of financial, administrative, and clinical management incentives and modalities with the clinical practices of the multidisciplinary team in charge of their health and social care’ [9, p. 3].

2. Health and health care system imperatives

Like all Western countries and many emerging countries, Québec faces a dual transition: a demographic transition (an ageing population) and an epidemiological transition (prevalence of chronic diseases over pandemic infections).

Québec has over 7.5 million people, of which 14.3% are aged 65 and over [10]. Fully 73% of persons 65 years of age and older suffer from at least one chronic health condition [11]. The population is ageing and the prevalence of chronic diseases is increasing faster in Québec than elsewhere in Canada [11, 12]. Multimorbidity is becoming the rule rather than the exception in the Québec health care system [13, 14], and its impact is felt in every part in the health care system. For example, 50% of the patients seen in primary care have five or more chronic diseases, which increases to more than 70% for persons aged 65 and over [15].

Chronic diseases have a significant impact on the health of the Québec population and influence quality of life, activity restriction, and mortality rates [13, 16].

Moreover, the management of chronic diseases poses challenges to quality of care. Some 30% of Canadians with a chronic disease report medical mistakes, medication errors or laboratory errors [17]. Poor discharge planning, lack of recommended care, and lack of a treatment plan are also frequently reported [2, 17–19], and this may lead to hospital readmission or visits to the emergency room [2]. In Québec, several gaps in quality of care have been also reported [20, 21].

3. Recent reforms in the province of Québec

The Quebec healthcare system is publicly funded with universal access to medical and hospital care. The system has a long history of integration at the structural level combining social services, community-oriented primary health services and home care through the CLSCs (Centre local de services communautaires). Nevertheless, silos still exist at the clinical level, particularly between acute and long-term care, between secondary and primary care, and between social and medical care, preventing persons with multiple chronic diseases from getting comprehensive and coordinated care.

3.1. Health and social service centres and local health and social services networks

3.1.1. Description

In December 2003, the National Assembly of Québec adopted a law entitled An Act respecting local health and social services network development agencies, which was expanded in November 2005 (An Act respecting health services and social services). The main objective of these changes was to improve accessibility, continuity, integration and quality of services for the population of a given area through the development of local organizational and clinical projects, in particular for persons with impairments or mental health problems and persons with chronic diseases [22].

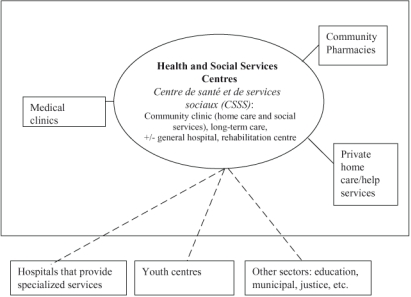

Ninety-five CSSS (Centre de santé et de services sociaux—Health and Social Services Centres) (shown at the centre of the figure in Graph 1) were created through the merger of several organizations operating in the same well-defined geographical area [23, 24]. CSSSs merge CLSC, long-term care centres and public or privately owned commissioned nursing homes (Centre d’hébergementet de soins de longue durée-CHSLD). In addition, 79 of these CSSSs also include a general hospital (Centre Hospitalier de Soins Généraux-CHSGS) and a rehabilitation centre.

Graph 1.

Health and social service centers and the local health and social services network (adapted from the Québec Ministry of Health and Social Services [23]).

These new CSSSs had to develop contractual agreements with other providers inside or outside their service areas to provide the services needed by the local population and create RLS (Réseaux locaux de services—Local Health and Social Services Networks). Other service providers include community pharmacies, volunteer agencies, medical clinics, tertiary-care university hospitals, youth centres, etc. Two principles served as the basis for the reform: a shift from a ‘service-based’ to a ‘population-based’ approach—meaning responsibility for accessibility, support, and health of the population of the health area—and a hierarchy of services (primary, secondary and tertiary care) [25].

The CSSSs are organized around nine programmes: public health, general services, people with impairments related to ageing, physical disability, intellectual disability, pervasive development disorders, youth in difficulty, dependencies, mental health and physical health. For instance, an intervention continuum has been developed for ageing-related loss of independence (PALV), which covers all prevention, healing and support interventions for persons with social or health problems generally associated with an ageing-related loss of functional independence [26].

Apart from these nine programmes, some CSSSs experiment or implement multidisciplinary teams based on the Chronic Care Model [27–29] in order to manage specific chronic diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes and depression. For instance, the Côte-des-Neiges diabetes management team (consisting of a coordinator, a community organizer, two nurses, a dietician, a foot care technician, a social worker and an exercise consultant) uses information technologies to collaborate with clinic-based physicians [30]. This experimental research programme was discontinued due to lack of secure long-term funding [26].

A network of integrated services for persons with COPD has been in development in Montreal since 2002 [31, 32]. The goal of this network is to provide integrated follow-up to persons with COPD through a group of partners, such as CSSSs, secondary home care with respiratory equipment (a regional service of home care for pulmonary patients), hospitals and attending physicians. An evaluation of this network is currently underway.

3.1.2. Evaluation

Results of an evaluation of the CSSSs deployment are not available yet. However, recent studies show that the different institutions of the healthcare system are becoming increasingly integrated, even if it is an ongoing process [21]. A philosophy of collective responsibility and a population-based approach has emerged [13]. There is greater alignment between organizational structures and the strategic vision of a population-based approach within CSSSs [24].

3.2. Primary care reform: family medicine groups and network clinics

3.2.1. Description

In Québec, primary care has traditionally been based on family physicians in private practice that are paid on a fee-for-service basis. The primary care system has endured several reforms over the last few years. Recently, the main organizational change has been the implementation of family medicine groups (GMFs—Groupes de Médecins de Famille) [33].

A Groupe de Médecins de Famille is a group of family physicians (6–12) who are collectively responsible for a large group of patients (1000–2200 patients per full-time equivalent physician) and work in close collaboration with the nurses in their clinic [22, 34, 35]. GMFs have been implemented in order to provide easier access to a family physician, extend the hours of access to family physicians, improve the quality of general medical care, improve patient follow-up and service continuity by strengthening links with other healthcare providers such as CSSSs, and avoid unnecessary visits to emergency rooms. The GMF reform supports the recruitment of nurses and administrative support staff and the acquisition of equipment (information technology). Sharing activities with nurses is deemed essential. The GMF reform depends on the implementation of advanced nurse practitioners—a new profession in Québec, rarely found until now in primary care. Recent legislation on sharing tasks and responsibilities across different health care professionals supports this transition [21]. While implementation is on a voluntary basis, there are some small financial incentives for family physicians [21], without significant changes to the dominant fee-for-service payment procedures [23]. In July 2010, there were 210 accredited GMFs [22].

3.2.2. Evaluation

The emergence of the GMFs represents an improvement in the organization of primary care [33, 36, 37]. Two multi-method studies conducted on the first GMFs to be implemented [36, 37] showed that the collaboration among physicians and between physicians and nurses have improved [36, 37]. Patient satisfaction has also increased as a result [37]: they perceive improvements in the accessibility to primary care [37], communication with the health professionals [37], physician nurse coordination, comprehensive care and their own education [36, 37]. Moreover, patients are more loyal to their GMF than comparable medical clinics [36, 37]. Job satisfaction among physicians has increased since they feel less isolated and less under a burden of heavy duties [37]. Nurses also report a very high satisfaction level [37]. In addition, a larger multi-method study conducted in 2005 on primary care services in Québec [33] showed that GMFs models promoting organizational accountability, longer-term patient management, and offering a mix of consultation options (e.g. walk-in clinics, by appointment or telephone consultations) maximize accessibility and continuity of care, particularly for patients with chronic diseases.

Network clinics (Cliniques réseau) represent the second phase of the strategic reorganization of primary care services and are currently being implemented. The aim of these clinics is to ensure better integration between the new CSSSs and family physicians, specifically in the Montreal area where integration is more challenging. The Montreal metropolitan area presents major challenges to integration due to: 1) the numerous physician clinics unevenly distributed over the area, 2) the various locations where physicians can practice (clinics regrouping family physicians and specialists, solo practices and institutions such as CLSCs, nursing homes and general hospitals) and 3) geographical concentration of hospitals with emergency departments in the downtown area [38]. To facilitate the integration process, the network clinics play a coordinator and liaison role with the CSSS. The network clinics give access to a complete range of primary care services, including consultations with and without an appointment, 365 days per year, 12 hours/day during the week and 8 hours/day during weekends and holidays. They also include on-call services outside of office hours for vulnerable patients, guaranteeing access to a physician at all times [38, 39]. It should be noted, however, that the effectiveness of these network clinics have not yet been evaluated.

3.3. Localized initiatives to improve integration

Apart from the reforms described in Sections 3.1 and 3.2, localized initiatives were also implemented to improve integration for persons with chronic diseases, particularly older persons. Several models have been developed and implemented in Québec in response to the fragmentation of care. The emphasis is on the transformation of the health care service configuration to improve health and utilization outcomes. While not providing an exhaustive list, this section provides and contrasts some illustrative examples.

3.3.1. Hospital models

These models were initiated in hospitals. More specifically, they were developed for inpatients (in emergency departments or units of care) or for outpatients.

Model developed for emergency departments:

Rapid emergency department intervention targets older patients in the emergency department who are at risk of functional decline and other adverse outcomes. The intervention comprises two steps: (1) identification of high-risk patients using a screening tool, and (2) a brief standardized nursing assessment to identify un-resolved problems, notify the family physician and home care providers, and make other referrals as required. Results of a multicentre randomized trial reveal that the intervention increased the rate of referrals to the patient’s family physician and home care services [40] and has helped people secure early provision of home care [41]. The intervention was associated with a significantly reduced rate of functional decline at 4 months [40] without increasing costs [42].

Models developed on units of care:

OPTIMAH (Optimizing care of hospitalized elderly persons) is a model that implements interventions in units of care and emergency departments in order to prevent functional decline related to geriatric syndrome and iatrogenic complications [43]. This approach is based on the principles of Acute Care for the Elderly [44]. When an older person is in the emergency department or is hospitalized in a unit of care, a mobile multidisciplinary geriatric team, led by a nurse, visits him/her. The nurse assesses risk factors with AINEES, a tool designed to measure vital signs in the elderly [45]. AINEES provides an overview of the older patient’s response to his or her care and treatments with a focus on independent living and falls, the integrity of skin, nutrition, elimination, cognitive state and behaviour, and sleep. Based on the assessment, the nurse develops a therapeutic plan and plays a leadership role with the treatment team and other caregivers. The implementation and impacts of this framework have not yet been evaluated.

Community-based integrated models

The SIPA model (Services intégrés pour les personnes âgées) was implemented in Montréal. Its goals were to respond appropriately to the needs of older persons with disabilities, to maintain and promote the independence of older persons and their capacity to make choices while respecting their dignity, and to optimize the use of community-, hospital- and institutional-based resources [46]. The model has the following characteristics: (1) an integrated system of community-based care, offering front and second-line health and social services, including short- and long-term care provided in both the community and institutions; (2) responsibility for providing care to a specific population; (3) a clinical model that includes all services; (4) a method of prepayment by capitation, coupled with financial responsibility for all services delivered; and (5) public management in accordance with the fundamental principles of the Canadian Health Act.

A randomized controlled trial examined the impact on utilization and cost of services, quality of care and the organization of services. The results showed that SIPA increased accessibility to health and social home care with more intense home health care and decreased hospital alternate-level inpatient stays (‘bed blockers’), and had the potential to reduce hospital and nursing home utilization with no difference in total overall costs [47]. Moreover, the satisfaction of SIPA caregivers increased, with no increase in caregiver burden [47].

Another coordination service, PRISMA (Programme de recherche sur l’intégration des services de maintien de l’autonomie), is based on six components: (1) coordination of decision makers and managers at the regional and local levels; (2) a single entry point; (3) a single assessment instrument coupled with a case-mix management system; (4) case management; (5) individualized service plans; and (6) a computerized clinical chart.

PRISMA has been evaluated in a population-based quasi-experimental study with three experimental and three comparison areas. The results on impact on functional decline were inconclusive, patient satisfaction was higher, patient empowerment was preserved and the number of visits to emergency rooms was lower than expected [48].

Based on the components of SIPA and PRISMA, the Québec Ministry of Health and Social Services supports the implementation of networks of integrated services for older persons (Réseaux de services intégrés aux personnesâgées—RSIPA). The implementation process is under evaluation.

Discussion

Québec has a history of strong integration of health and social services [13]. Recent evaluations of the current reform designed to integrate all health and social care services in each geographical territory showed that the various institutions of the healthcare system are becoming more integrated [21].

This literature review suggests that some components are paramount to the integration of the health care system: 1) homogeneity of the goals across the multiple levels of the system: financial, organizational and clinical level; 2) a health care system rooted in primary care; 3) specialized services in support of primary care; 4) comprehensive assessment of patients’ needs; 5) implementation of case managers for patients with multiple and compounding health and social problems; 6) enhanced interdisciplinary practices, particularly close collaboration between nurses practitioners and family physicians; 7) coordination of patients’ trajectories and patients’ transitions across multiple health and social services and multiple settings (e.g. GMFs, hospitals, nursing homes); 8) information exchanges between professionals, providers and settings, ideally through the implementation of a shared clinical and administrative record; 9) measures of system outcomes and their links to patient outcomes in order to favor continuous quality and management improvement.

However, the implementation of such components presents many challenges. A consultation of Québec experts [13, 21] and various studies [13, 24, 25, 36, 37, 49] outlined the three greatest challenges:

reorganization of primary care,

integration of primary and secondary care, and

efficient governance and change management.

4.1. Reorganization of primary care

The organization of primary care is still unsatisfactory. A large proportion of people with complex health needs have no family physician. The implementation of GMFs provides some hope of a solution, but building primary care teams and developing interdisciplinary practices remains a challenge [32]. For example, family physicians have found it difficult to change their practices from working alone to collaborating with the nurse practitioners within the GMFs, and some physicians practice as if nurse practitioners were not available [49]. In primary care, case management is still very limited. Another barrier to the implementation of an integrated approach (such as case management and coordination of services) is the fee-for-service for physicians [21].

Despite these barriers, there are some encouraging signs. Administrative and nursing staff, newly available in GMFs, help structure key components of primary care reform [36, 37, 49]. Interdisciplinary work takes time to implement [36, 37] and may be facilitated by establishing a relationship of trust and a vision shared by all physicians that nurses be considered collaborators rather than assistants [36, 37]. Interdisciplinary collaboration can be further facilitated by having physicians and nurses jointly develop the follow-up protocols and by dedicating time and space for communication [36, 37]. These arrangements promote a common understanding of goals pursued through clinical team work and help overcome interprofessional conflicts [49]. In addition, patient empowerment through education, shared decision-making, and access to medical records might facilitate the current reform [50]. Nevertheless, we still need to know more about the nature of relationships in interdisciplinary teams [30] and determine efficient processes for implementing interdisciplinary care [51].

4.2. Integration of primary and secondary care

The current reforms demonstrate that one of the ongoing weaknesses lies in poor collaboration between primary and secondary care. Difficulties are still being encountered at the structural level in specifying the responsibilities of primary and secondary care [25]; however negotiations between GMFs and their CSSS are in progress [21, 25, 37]. The target population for primary and secondary care still needs to be determined based on the degree of complexity of the patient. Localized initiatives tested in Quebec have been mostly designed either for primary or secondary care. The performance of care processes is still assessed in silos and performance in terms of overall patient trajectories has yet to be evaluated [25]. Canada and Quebec in particular continue to face difficulties in patient access to care due to the insufficient number of family physicians and specialists [3]. The heavy workload imposed on these professionals created an additional barrier to their collaboration.

At the clinical level, primary care and secondary care are provided in parallel, and significant coordination problems remain [9]. One of the major barriers to coordination are gaps in clinical information sharing and a significant lag in the use of information technologies [3, 13, 25, 36] as well as difficulties adopting and using some of the electronic medical records that have been implemented [30, 52]. There is a recognition in Québec that care provided before, during and after a hospitalization should be integrated, but no concrete actions have been entertained in this area [53]. Transition models are an avenue for development in Quebec. These models are based on a range of actions to ensure coordination and continuity of health care [54, 55]. They refer to a range of time-limited services and environments designed to ensure health care continuity and avoid preventable poor outcomes in at-risk populations as they move from one level of care to another, among multiple providers, and/or across settings. Ideally, these models are comprehensive (across diseases, providers and settings) and longitudinal, with linkages across sites of care and between medical and social services [56]. They strive for coordination between the goals of patients, caregivers, family members and healthcare providers [56]. Different models have been successfully implemented in the US where they have been proven efficient: patients were less likely to be rehospitalized [57, 58], health outcomes were improved, and health care costs were reduced [59–61].

4.3. Governance and change management

In terms of governance, there are three challenges: 1) to effectively coordinates pre-existing entities (hospitals, nursing homes, and community-based services) merged into CSSSs, 2) to develop local health and social services networks with providers in the community, and 3) to adopt a population-based approach [24].

Recent studies show that there is still inadequate clinical governance in CSSS-based services: lack of support for clinical decisions (lack of information systems, shared patient records, guidelines and care protocols) [21]. Organizational governance is also sometimes lacking [21]. Clinical services continue to operate in silos, even within the CSSSs [21]. Hierarchies are expanding and bureaucracy is increasing [25], while the implementation of 95 CSSSs with responsibility for promoting population health and delivering services should have encouraged decentralization. A sure sign of the push for centralization is the paperwork that is imposed on local medical clinics to obtain their GMF status [36]. The focus is on standardizing structures and practices, which is perceived as preventing adaptation to the local context [21]. Organizational culture is rarely focused on performance evaluation [25]. There remains poor financial integration within the healthcare system: there are financial silos between institutions and programmes [21], a lack of financial accountability for the population of a geographical area [21], and the payment of professionals is not related to performance of services [21].

Despite these challenges, there are encouraging signs. In some cases, regional authorities have been instrumental in the implementation of recent reforms [25, 36, 37]. Moreover, expertise in public health is well developed and structured in Québec [13, 21] and competencies are being developed in the organization of care [21]. Integration is facilitated by governance with a clear mission and vision, strong leadership and change management strategies. Moreover, studies show that the integration process is facilitated by the emergence of a local leadership within CSSSs and GMFs [25, 30, 36, 37, 49]. It is essential to have a leader—a ‘sense-maker in chief’—who plays a critical role in shaping the direction of the current reform [24]. This leader needs to have in-depth knowledge and experience in the organization and be able to foster a sense of continuity by connecting the current transformation to historical antecedents and past experiences [24]. Two other facilitators are good communication and consultation mechanisms established by the CSSSs and a tradition of partnership between the various institutions, with increasing accountability supported by a culture of continuous quality improvement and ongoing performance measurement [25]. In addition, a mixed payment structure for family physicians and for a subset of medical specialists is slowly being implemented including higher fee-for-services for vulnerable patients and fixed amounts for administrative and coordination tasks [21].

5. Conclusion

Solutions are needed for managing chronic diseases, and many reforms and localized initiatives are addressing the problem. Despite reforms, changes and reorganizations, the Québec health system is struggling to deal with the challenge of patients with a single chronic illnesses [13], let alone patients with multiple chronic diseases. To meet this challenge, a strategic implementation of clinical, technological and organizational changes is required to provide patient-centered care: strengthening primary care, implementing a shared information system, and improving collaboration between primary and secondary care.

Québec also needs to develop health services research [25], since there are major gaps in the knowledge needed for optimal healthcare of a large and increasing population of adults with multiple chronic conditions, as well as a lack of widespread translation and implementation of interventions shown to be effective. There is still a shortage of scientific information for appraising the efficiency and effectiveness of the proposed models [13, 51].

Québec has many assets for achieving a successful transformation, including its integration of health and social services and many innovative projects and programmes that have been tested in different parts of the health system.

Acknowledgments

Muriel Gueriton and Catherine Galzin, Librarians, provided help with the literature search. The research was supported by the Université de Montréal Public Health Research Institute; the Canadian Institutes of Health Research; the Dr. Joseph Kaufmann, Chair in Geriatric Medicine, McGill University and the Lady Davis Institute (Jewish General Hospital). The sponsors played no role in the study design; the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. No conflict of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Isabelle Vedel, Solidage-McGill University-Université de Montreal Research Group on Frailty and Aging, Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Community Studies, Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research, Jewish General Hospital, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Michele Monette, Solidage-McGill University-Université de Montreal Research Group on Frailty and Aging, Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Community Studies, Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research, Jewish General Hospital, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

François Beland, Department of Health Administration, Université de Montreal, Solidage-McGill University-Université de Montreal Research Group on Frailty and Aging, Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Community Studies, Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research, Jewish General Hospital, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Johanne Monette, Division of Geriatric Medicine, McGill University, Solidage-McGill University-Université de Montreal Research Group on Frailty and Aging, Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Community Studies, Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research, Jewish General Hospital, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Howard Bergman, Division of Geriatric Medicine, McGill University, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

6. Reviewers

Gina Browne, PhD, RegN, HonLLD, Founder and Director, Health and Social Service Utilization Research Unit; Professor, Nursing; Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics; and Ontario Training Centre in Health Services and Policy Research (OTC) MOHLTC Theme Lead—Innovative and Integrated Systems of Prevention and Care McMaster University—McMaster Innovation Park, Ontario, Canada

Yves Couturier, MSS, PhD, Canada Research Chair in Professional Practices in Integrating Gerontology Services, Research Center on Ageing, University of Sherbrooke, Canada

Margaret MacAdam, PhD, Associate Professor (Adjunct), Faculty of Social Work, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada

References

- 1.Tsasis P, Bains J. Chronic disease: shifting the focus of healthcare in Canada. Healthcare Quarterly. 2009;12(2):e1–11. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2009.20597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoen C, Osborn R, How SKH, Doty MM, Peugh J. In chronic condition: experiences of patients with complex health care needs, in eight countries. Health Affairs. 2008;28:1–16. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.w1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schoen C, Osborn R, Doty MM, Squires D, Peugh J, Applebaum S. A survey of primary care physicians in eleven countries. Perspectives on care, costs, and expériences. Health Affairs. 2009;28:1171–83. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.6.w1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacAdam M. Framework of integrated care for the elderly: a systematic review. Ontario: Canadian Policy Research Network; 2008. [cited 27 January 2011]. Available from: www.cssnetwork.ca/Resources%20and%20Publications/MacAdam-Frameworks%20for%20Integrated%20Care%20for%20the%20Frail%20Elderly.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marchildon GP. Health systems in transition: Canada. Copenhagen: European observatory on health systems and policies; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leutz WN. Five laws for integrating medical and social services. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. 1999;77:77–110. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nies H, Berman PC. Integrating services for older persons. Dublin: European Health Management Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kodner DL, Spreeuwenberg C. Integrated care: meaning, logic, applications, and implications—A discussion paper. International Journal of Integrated care [serial online] 2002 Nov 14;:2. doi: 10.5334/ijic.67. Available from: http://www.ijic.org. URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Béland F. Service integration (geriatric) In: Stone JH, Blouin M, editors. International Encyclopedia of Rehabilitation; 2010. [cited 27 January 2011]. Available from: http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/encyclopedia/en/pdf/integration_of_service_geriatric.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Institut de la statistique Québec. Population selon le grouped’âge, régionsadministratives. [Population of administrative regions by age]. Québec: Institut de la statistique Québec; 2006. [cited 28 January 2011]. Available from: http://www.stat.gouv.qc.ca/regions/lequebec/population_que/poptot20.htm. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Health Council of Canada. Population patterns of chronic health conditions in Canada: a data supplement to why health care renewal matters: learning from Canadians with chronic health conditions. Toronto: Health Council; 2007. [cited 27 January 2011]. Available from: http://www.healthcouncilcanada.ca/docs/rpts/2007/outcomes2/Outcomes2PopulationPatternsFINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cazale L, Dumitru V. Les maladies chroniques au Québec: quelques faits marquants. [Chronic diseases in Québec: some notable facts]. Zoom Santé: Série Enquête sur la santé dans les collectivités canadiennes; 2008. Québec: Institut de la statistique du Québec; [cited 27 January 2011]. Available from: http://www.stat.gouv.qc.ca/publications/sante/pdf2008/zoom_sante_mars08.pdf. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Commissaire à la santé et au bien-être. Rapport d’appréciation de la performance du système de santé et de services sociaux: État de situation portant sur les maladies chroniques et la réponse du système de santé et de services sociaux. [Appreciation report on the performance of the health care system and social services: Present situation on chronic diseases and a response from the health and social services system]. Québec: Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux du Québec; 2010. [cited 27 January 2011]. Available from: http://www.csbe.gouv.qc.ca/index.php?id=324. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cazale L, Laprise P, Nanhou V. Maladies chroniques au Québec et au Canada: évolution récente et comparaisons régionales. Vol. 17. [Chronic diseases in Québec and Canada: recent evolution and regional comparisons]. Zoom Santé: Série Enquête sur la santé dans les collectivités canadiennes; 2009. pp. 1–8. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fortin M, Bravo G, Hudon C, Vanasse A, Lapointe L. Prevalence of multimorbidity among adults seen in family practice. Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3(3):223–8. doi: 10.1370/afm.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fortin M, Dubois M-F, Hudon C, Soubhi H, Almirall J. Multimorbidity and quality of life: a closer look. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2007;5(52) doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schoen C, Osborn R, Huynh PT, Doty MM, Zapert K, Peugh J, et al. Taking the pulse of health care systems: experiences of patients with health problems in six countries. Health Affairs. [serial online] 2005 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.509. Suppl Web Exclusives:w5-509-w5-525. [cited 27 January 2011]. Available from: http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/early/2005/11/28/hlthaff.w5.509.full.pdf+html?sid=28a40b22-18a7-4bb3-bc05-d9998c3a1fae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Health Council of Canada. Safer health care for “Sicker” Canadians: International comparisons of health care quality and safety. Toronto: Health Council; 2009. [cited 27 January 2011]. Available from: http://healthcouncilcanada.ca/bulletinone.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Health Council of Canada. Helping patients help themselves: are Canadians with chronic conditions getting the support they need to manage their health? Toronto: Health Council; 2010. [cited 21 September 2010]. Available from: http://www.healthcouncilcanada.ca/docs/rpts/2010/AR1_HCC_Jan2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCusker J, Roberge D, Vadeboncoeur A, Verdon J. Safety of discharge of seniors from the emergency department to the community. Healthcare Quarterly. 2009;12:24–32. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2009.20963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levesque JF, Feldman D, Dufresne C, Bergeron P, Pinard B, Gagné V. Barrières et éléments facilitant l’implantation de modèles intégrés de prévention et de gestion des maladies chroniques. [Barriers and elements facilitating the establishment of integrated models of prevention and management of chronic diseases.]. Pratiques et Organisation des Soins. 2009;40(4):251–65. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux du Québec. Family medicine group: what is a family medicine group? [webpage on the internet]. c2010 [cited 27 January 2011]. Available from: http://www.msss.gouv.qc.ca/en/sujets/organisation/gmf.php. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux du Québec. Centres de santé et de services sociaux—RLS. [Local Services Networks and Health and Social Services Centres]. [webpage on the internet]. c2010 [cited 27 January 2011]. Available from: http://www.msss.gouv.qc.ca/reseau/rls/index.php. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denis JL, Lamothe L, Langley A, Breton M, Gervais J, Trottier LH, et al. The reciprocal dynamics of organizing and sense-making in the implementation of major public-sector reforms. Canadian Public Administration. 2010;52(2):225–48. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux du Québec. Évaluation de l’implantation des réseaux locaux de services de santé et de services sociaux. [Evaluation of the establishment of health care and social services local networks]. Québec: Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux du Québec; 2010. [cited 27 January 2011]. Available from: http://msssa4.msss.gouv.qc.ca/fr/document/publication.nsf/961885cb24e4e9fd85256b1e00641a29/02e649500fa292958525775a0060cfc4?OpenDocument. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Direction de la gestion de l’information et des connaissances. Le continuum d’intervention «Perte d’autonomie liée au vieillissement». [The continuum of intervention- “Loss of autonomy related to ageing”]. Longueuil: Agence de développement de réseaux locaux de services de santé et de services sociaux de la Montérégie; 2005. [cited 27 January 2011]. Available from: http://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/bs78748. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Affairs. 2001;20(6):63–80. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(14):1775–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, Part 2. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(15):1909–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Civita M, Dasgupta K. Using diffusion of innovations theory to guide diabetes management program development: an illustrative example. Journal of Public Health. 2007;29:263–8. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdm033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Régie régionale de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal-Centre. Vers un réseau de services intégrés destinés aux personnes atteintes de maladies pulmonaires obstructives chroniques (MPOC): éléments essentiels de la mise en œuvre. [Towards a network of integrated services intended for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): essential components of the implementation]. Montréal: Régie régionale de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal-Centre; 2002. [cited 27 January 2011]. Available from: http://www.cmis.mtl.rtss.qc.ca/pdf/publications/isbn978-2-89510-507-7.pdf. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lemoine O, Simard B, Couture A, Leroux C, Roy Y, Tousignant P, et al. Le suivi des personnes souffrant d’une maladie pulmonaire obstructive chronique (MPOC) en 2005-2006: portrait de certaines interventions en lien avec le réseau de services intégrés. [A follow-up on people suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 2005-2006: a portrait of certain interventions linked to the network of integrated services]. Montréal: Direction de la santé publique, Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec; 2009. [cited 27 January 2011]. Available from: http://www.inspq.qc.ca/pdf/publications/928-CLSCetMPOC2005-2006.pdf. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pineault R, Levesque JF, Roberge D, Hamel M, Lamarche P, Haggerty J. Accessibility and continuity of care: a study of primary healthcare in Québec. Montreal: Agence de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal, Institut national de santé publique, Centre de recherche de l’Hôpital Charles Lemoyne; 2009. [cited 21 September 2010]. Available from: http://www.inspq.qc.ca/pdf/publications/911_ServicesPremLigneANGLAIS.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ordre des infirmiers et infirmières du Québec/Fédération des médecins omnipraticiens du Québec. Rapport du Groupe de travail OIIQ/FMOQ sur les rôles de l’infirmière et du médecin omnipraticien de première ligne et les activités partageables. [Report of the work group OIIQ/FMOQ on the rules of nurse and primary care physician and shared activities]. Montréal: Ordre des infirmiers et infirmières du Québec/Fédération des médecins omnipraticiens du Québec; 2005. [cited 27 January 2011]. Available from: http://www.oiiq.org/uploads/publications/autres_publications/OIIQ_FMOQ.pdf [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux du Québec. Le groupe de médecine de famille: un atout pour le patient et son médecin—Dépliant. [The family medicine group—an asset for the patient and for the patient’s doctor]. Montréal: Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux du Québec; 2005. [cited 21 September 2010]. Available from: http://msssa4.msss.gouv.qc.ca/fr/document/publication.nsf/ad3286171667c9a18525681500530bd0/93c4226d9e2377e4852575040057199c?OpenDocument. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beaulieu MD, Denis JL, D’Amour D, Goudreau J, Haggerty JL, Hudon E, et al. L’implantation des Groupes de médecine de famille : le défi de la réorganisation de la pratique et de la collaboration interprofessionnelle. [Implementing family medicine groups: The challenge in the reorganization of practice and interprofessional collaboration]. Montréal: Chaire Docteur Sadok Besrour en médecine familiale, Université de Montréal; 2006. [cited 27 January 2011]. Available from: http://www.medfam.umontreal.ca/chaire_sadok_besrour/ressources/publications.html. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Équipe d’évaluation des GMF, Direction de l’évaluation. Évaluation de l’implantation et des effets des premiers groupes de médecine de famille au Québec, Évaluation Santé et Services sociaux. [Evaluation of the establishment and of the effects of the first groups of family medicine doctors in Québec, Health and Social Services Evaluation]. Québec: Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux du Québec; 2008. [cited 27 January 2011]. Available from: http://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/acrobat/f/documentation/2008/08-920-02.pdf. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Département régional de médecine générale de Montréal, Agence de la santé et de services sociaux de Montréal. Les cliniques-réseau. [Network-Clinics]. [webpage on the internet]. c2010. [cited 27 January 2011]. Available from: http://www.santemontreal.qc.ca/fr/drmg/cli_res.html. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Département régional de médecine générale de Montréal. Cadre de référence pour l’implantation des cliniques-réseau. [Network-Clinic Frame of Reference.] Montréal: Agence de la santé et de services sociaux de Montréal; 2006. [cited 27 January 2011]. Available from: http://www.santemontreal.qc.ca/pdf/cma_cadre.pdf. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCusker J, Verdon J, Tousignant P, de Courval LP, Dendukuri N, Belzile E. Rapid emergency department intervention for older people reduces risk of functional decline: results of a multicenter randomized trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2001;49(10):1272–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCusker J, Dendukuri N, Tousignant P, Verdon J, Poulind C, Belzile E. Rapid two-stage emergency department intervention for seniors: impact on continuity of care. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2003;10(3):233–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCusker J, Jacobs P, Dendukuri N, Latimer E, Tousignant P, Verdon J. Cost-effectiveness of a brief two-stage emergency department intervention for high-risk elders: results of a quasi-randomized controlled trial. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2003;41(1):45–56. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lafrenière S, Dupras A. OPTIMAH ou comment mieux soigner les ainés à l’urgence et dans les unités de soins aigus. [OPTIMAH or how to better look after the elderly in the emergency room and units of acute care.]. Le Journal des Soins Infirmiers du CHUM. 2008;8(3):1–4. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palmer RM, Counsell S, Landefeld CS. Clinical intervention trials: the ACE unit. Clinical Geriatric Medicine. 1998;14(4):831–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fulmer T. How to try this: Fulmer SPICES. American Journal of Nursing. 2007;107(10):40–8. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000292197.76076.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beland F, Bergman H, Lebel P, Dallaire L, Fletcher J, Contandriopoulos AP, et al. Integrated services for frail elders (SIPA): a trial of a model for Canada. Canadian Journal on Aging. 2006;25(1):5–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beland F, Bergman H, Lebel P, Clarfield AM, Tousignant P, Contandriopoulos AP, et al. A system of integrated care for older persons with disabilities in Canada: results from a randomized controlled trial. Journals of Gerontology Series A-Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2006;61(4):367–73. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hébert R, Raîche M, Dubois MF, Gueye NR, Dubuc N, Tousignantt M, et al. Impact of PRISMA, a coordination-type integrated service delivery system for frail older people in Québec (Canada): a quasi-experimental study. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2010;65:107–18. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodriguez C, Pozzebon M. The implementation evaluation of primary care groups of practice: a focus on organizational identity. BMC Family Practice [serial online] 2010;11(15) doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-15. Available from : http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2296/11/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McMurchy D. What are the critical attributes and benefits of a high-quality primary healthcare system? Toronto: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gogovor A, Savoie M, Moride Y, Krelenbaum M, Montague T. Contemporary disease management in Québec. Healthcare Quarterly. 2008;11(1):30–7. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2013.19495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lapointe L, Rivard S. Getting physicians to accept new information technology: insights from case studies. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2006;174(11):1573–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.La Direction des ressources humaines de l’information et de la planification . Approche gériatrique transhospitalière. [Trans-hospital geriatric approach]. Montréal: Agence de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal; 2008. [cited 27 January 2011]. Available from: http://www.cmis.mtl.rtss.qc.ca/pdf/publications/isbn978-2-89510-571-8.pdf. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Coleman EA, Boult C, American Geriatrics Society Health Care Systems Committee Improving the quality of transitional care for persons with complex care needs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(4):556–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arbaje AI, Maron DD, Yu Q, Wendel VI, Tanner E, Boult C, et al. The geriatric floating interdisciplinary transition team. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010;58(2):364–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Norris SL, High K, Gill TM, Hennessy S, Kutner JS, Reuben DB, et al. Health care for older Americans with multiple chronic conditions: a research agenda. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56(1):149–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(17):1822–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parry C, Min SJ, Chugh A, Chalmers S, Coleman EA. Further application of the care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial conducted in a fee-for-service setting. Home Health Care Services Quarterly. 2009;28(2-3):84–99. doi: 10.1080/01621420903155924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, Jacobsen BS, Mezey MD, Pauly MV, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281(7):613–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.7.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52(5):675–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Naylor MD, Feldman PH, Keating S, Koren MJ, Kurtzman ET, MacCoy MC, et al. Translating research into practice: Transitional care for older adults. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2009;15(6):1164–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]