Abstract

Introduction

The Swiss health care system is characterized by its decentralized structure and high degree of local autonomy. Ambulatory care is provided by physicians working mainly independently in individual private practices. However, a growing part of primary care is provided by networks of physicians and health maintenance organizations (HMOs) acting on the principles of gatekeeping.

Towards integrated care in Switzerland

The share of insured choosing an alternative (managed care) type of basic health insurance and therefore restrict their choice of doctors in return for lower premiums increased continuously since 1990. To date, an average of one out of eight insured person in Switzerland, and one out of three in the regions in north-eastern Switzerland, opted for the provision of care by general practitioners in one of the 86 physician networks or HMOs. About 50% of all general practitioners and more than 400 other specialists have joined a physician networks. Seventy-three of the 86 networks (84%) have contracts with the healthcare insurance companies in which they agree to assume budgetary co-responsibility, i.e., to adhere to set cost targets for particular groups of patients. Within and outside the physician networks, at regional and/or cantonal levels, several initiatives targeting chronic diseases have been developed, such as clinical pathways for heart failure and breast cancer patients or chronic disease management programs for patients with diabetes.

Conclusion and implications

Swiss physician networks and HMOs were all established solely by initiatives of physicians and health insurance companies on the sole basis of a healthcare legislation (Swiss Health Insurance Law, KVG) which allows for such initiatives and developments. The relevance of these developments towards more integration of healthcare as well as their implications for the future are discussed.

Keywords: integrated care, physicians’ networks, chronic disease management, Switzerland

The Swiss healthcare system

Switzerland is a democratic federal state of approximately 7 million inhabitants, in which government responsibilities are divided between three levels: the federal level, the 26 cantons and the municipalities. The main feature of the Swiss healthcare system is its decentralized structure and therefore the relatively high degree of local autonomy. Indeed, Switzerland is considered to have 26 slightly different healthcare systems, one for each canton, acting autonomously in the organization of healthcare services in their area. Due to subsidiarity, responsibilities are always assigned to the lowest of these levels. Universal access to health care is guaranteed since 1996 (mandatory health insurance), and the basic health insurance coverage includes a comprehensive package of health benefits, identical for all insured. Insurers are obliged to accept applicants, theoretically avoiding risk-selection across insurance companies. However, since the risk adjustment system has only poor performance, risk-selection remains a problem. Ambulatory care is provided by physicians working mainly independently in individual private practices. However, a growing part of primary care is provided by small group practices, as well as networks of physicians and health maintenance organizations (HMOs) acting on the principles of gatekeeping. Apart from patients who choose to restrict their choice of doctors in return for lower premiums (alternative—managed care—insurance models allowing patients to receive care from physician networks or HMOs), patients have direct and unrestricted access to primary care physicians and specialists. While independent private practitioners are paid fee-for-services, physicians working in networks or HMO’s may be paid either on a fee-for-service basis or by salary [1, 2]. Acute inpatient care is provided by cantonal and publicly subsidized hospitals and to a smaller extend (25%) by private for-profit and not-for-profit hospitals. Inpatient care for patients with basic health insurance is financed by the cantons and the health insurance companies. The latter cover a maximum of 50% of the costs of the inpatient treatment whereas the cantons meet the remaining costs including investments [2, 3]. Spending for health care in Switzerland is the third highest, after the USA and France, as expenditure per capita as well as a share of GDP amongst OECD countries [4].

Similarly to what is noticed in other countries, the Swiss population is ageing. Projections estimate that the percentage of individuals aged 65 years and over will increase from 16% in 2005 to 28% in 2050 [5]. This ageing of the population is accompanied by a discrete increase in life expectancy, that reached 83.7 years at birth for women (78.6 years for men) in 2004 (89.5 years and 85 years estimated, respectively for women and men in 2050), and by an overall decrease in mortality. While life expectancy in Switzerland is above EU averages, mortality rates in Switzerland are below EU averages.

Measures of prevalence of risk factors and diseases help estimate the burden of disease and its evolution over time. In Switzerland, tobacco use places the greatest burden on the Swiss population, followed by high blood pressure, overweight, high cholesterol and alcohol consumption. While the prevalence of smoking, between 1992 and 2007, has been declining both for men and women and most age groups, the prevalence of overweight has been increasing [6, 7]. The prevalence of chronic conditions has augmented markedly. Indeed, while 43% of adult Swiss residents self-reported at least one chronic condition in 1997, 51% did so in 2007. Projections based on epidemiological data estimate that the prevalence of chronic diseases representing the main causes of death, such as diabetes, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, will increase by at least 50% in 2030 [8].

Emergence of integrated care in Switzerland

Integrated care is a polymorphous concept viewed and understood very differently between national systems as well as between the various actors within the health systems. In general, integrated care is a “coherent set of methods and models on the funding, administrative, organisational, service delivery and clinical levels designed to create connectivity, alignment and collaboration within and between the cure and care sectors” in order to overcome well-known shortcomings in health care such as the fragmentation of cure and care (processes), the concerns for equal access or the inefficiencies of and within the health systems [9]. A recent systematic review summarizing the current research literature on health system integration suggested 10 key elements for successful integration: 1) comprehensive services across the care continuum, 2) patient focus, 3) geographic coverage and access, 4) standardized care delivery through interprofessional teams, 5) performance management, 6) information systems, 7) organizational culture and leadership, 8) physician integration, 9) governance structure and 10) financial management [10]. It is important to note that while there is a wide spectrum of integrated care activities throughout the world, these key elements may represent universal principles and therefore may be helpful to assess specific developments.

In Switzerland, two types of integrated care organizations have been developed since 1990: physician networks and HMOs. Physician networks are defined as organizations which “provide healthcare services geared to the requirements of the patients by means of contractually agreed cooperation among themselves, with service providers outside the network and with the insurance companies” [11]. Given this definition, Swiss physician networks represent hybrid forms or a mixture of integrated medical groups (IMG) and individual practice associations (IPA). There are two types of HMOs. In the staff model, the physicians are employed by the insurance company owning the HMO. For the group model, the physicians are the owners of the HMO which is also true for the physician networks. What all these organizations have in common is the principle of gatekeeping: the insured persons commit to always enter the healthcare system through the same entrance—or ‘gate’—if they develop medical problems. This gate may be a physician network, an HMO or a medical call centre reached by telephone. Specialized treatment or in-hospital treatment can be obtained only by presenting a referral from a gatekeeper or care manager. In return, the insured are given a discount on their premiums. Emergencies are exempted from this obligation, and special provisions apply to visits to gynaecologists and paediatricians.

According to Santesuisse, the association of health insurers in Switzerland, the share of insured people choosing an alternative (managed care) type of basic health insurance increased continuously since 1990: in 2010, only 56.4% had regular health insurance (down from 75.4% in 2008), 11.2% had managed care health insurance including GP’s sharing financial responsibility (capitation) (up from 6.5% in 2008) and 32.4% had a managed care type of health insurance without financial responsibility of GP’s (up from 24.6% in 2008) [Personal communication Axel Reichlmeier, Santesuisse: data of October 2010].

Survey of Swiss physician networks and HMOs

For the past 10 years the development of physician networks and HMOs in Switzerland has been evaluated at one- or two-year intervals. In the 2010 survey, data has been collected by an online questionnaire from all physician networks and HMOs in Switzerland under contract to one or several health insurance companies [13]. All networks and HMOs with contracts with one or more health insurers were eligible for the survey. The questionnaire has been developed specifically for this survey and covers the following aspects: (1) legal form of the network, (2) number of insured cared for by the network, (3) number of physicians in the network, (4) financial co-responsibility of the network, (5) kind of activities for quality improvement in the network, (6) information technology used in the network, (7) disclosure of performance measures by the network, (8) kind of contractual cooperation between the network and other care providers, (9) number and type of preferred provider of the network and (10) form of management of the network.

Prior to the survey, all physician networks and HMOs in Switzerland received a letter of invitation including a personalized link to the online questionnaire by email. The representatives of the networks/HMOs were asked to complete the questionnaire within six weeks. Data of organizations not completing the questionnaire was gathered by telephone interviews with their representatives. We got data from all networks and HMOs with contracts with one or more health insurers. The survey was funded by the Swiss Forum Managed Care [14].

Results of the 2010 survey

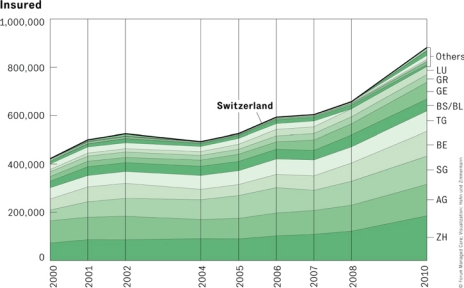

In 2010, an average of one out of eight insured person in Switzerland, and one out of three in the regions in north-eastern Switzerland, opted for the provision of care by general practitioners in physician networks or HMOs. This represented an increase of 34% in comparison with 2008 (maximum increase, 52%, in the canton of Zurich) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Insured with alternative health plans per canton in Switzerland 2000–2010.

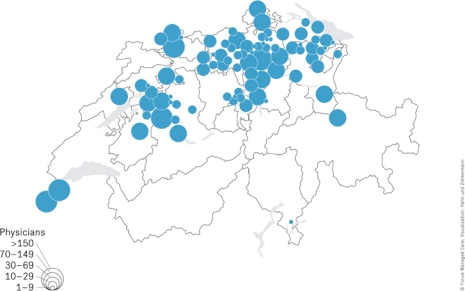

The geographical distribution of the 86 current networks of physicians, and the number of doctors affiliated with them is shown in Figure 2. The north-eastern regions of Switzerland as well as several other cantons (e.g. Geneva and Aargau) show an above-average percentage of networks. In contrast, physician networks are (still) non-existent in some parts of Switzerland—especiallyin the French- and Italian-speaking regions (except the canton of Geneva). In Switzerland as a whole, 54% of all basic care providers (3488 of total 6418 general practitioners, i.e., specialists in general medicine, internists and paediatricians) and more than 400 other specialists have joined the 86 physician networks. Out of 86 networks, 73 (84%) have contracts with healthcare insurance companies with which they agree to assume budgetary co-responsibility, i.e., to adhere to set cost targets for particular groups of patients. The members of the physician networks are convinced that the growth and expansion of integrated care will continue. Indeed, 55% of those questioned in the 2010 survey expect the number of insured persons to increase by up to 10% annually, while 26% expect it to increase by up to 20% annually, over the next three years.

Figure 2.

Physician networks and number of affiliated doctors in Switzerland (2010).

Nearly all the physician networks have implemented one or more quality management elements. The focus here is on quality circles, which 96% of the networks commit to implement. These circles, which are compulsory for the doctors, are held with a median frequency of eight times a year (range: 4–20 times a year). Other implemented quality management elements include critical incident reporting (CIRS, 53%), use of guidelines (41%), and contractually agreed disclosure of quality and/or cost data to health insurers (55%). More than half of the networks (58%) demonstrate their quality management work by means of a regular report sent to external stakeholders (43%) and/or a quality certificates (40%).

Almost half of the networks (43%) engage in contractually regulated collaboration with other (external) service providers—in particular, with hospitals (36%), emergency services (33%) and call centres (19%). Likewise, about half of the networks (51%) work with—and primarily refer their patients to—‘preferred providers’; these are most often specialists (45%), hospital doctors (35%), physiotherapists (27%), radiology institutes (27%) and laboratories (23%). These ‘preferred providers’ are selected on the basis of personal experience (45%) and/or of results from the quality circles (44%); other factors that play a role in selection are quality data (31%) and/or patient evaluations (28%).

Do physician networks improve efficiency and quality of care?

The survey presented above illustrates the development of physician networks in Switzerland. However, there are two important questions remaining: to what extent do they reduce or stabilize healthcare costs and to what extent do physician networks foster the quality of care?

Cost savings of physician networks and HMOs in Switzerland have been studied repeatedly with mixed results [15]. Early studies evaluating the impact of gatekeeping by physician networks on utilization and financial outcomes indicated transfer of visits from specialists to general practitioners and reduced costs; the findings were ambiguous due to incomplete case mix adjustment, however [16, 17]. In contrast, a more recent study evaluated the extent to which lower costs in a gatekeeping plan compared with a fee-for-service plan were attributable to more efficient resource management, or explained by risk selection. The authors showed that the estimated cost savings achieved by replacing fee-for-service based health insurance with gatekeeping in the source population amounted to 15%–19% per person not attributable to mere risk selection [18].

Results regarding the impact of physician networks on the quality of care are still sparse. A recent study assessed whether physician networks met a set of 43 self-reported indicators of quality of care (organization and structure, collaboration, process management, communication, results) [19]. The results showed that on average, the 19 participating networks met 69% of the 43 quality indicators. However, the results varied markedly between the physician networks (47.4%–81.8 %). In another recent study, physicians working in various types of practices (physician networks, group and single-handed practices) were asked to assess the extent to which patients with chronic illnesses were receiving care congruent with the Chronic Care Model (CCM), using the Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (ACIC) questionnaire. The authors showed that physician networks’ practices seemed to implement the different component of the CCM in a greater extent than group and single handed practices [20].

Despite these encouraging data, views and opinions on integrated care differ in Switzerland. Indeed, physicians from the French- and Italian-speaking part of Switzerland, in particular, view the development of physician networks with scepticism. Results from a recent survey asking physicians in the (French-speaking) canton of Geneva to complete a brief questionnaire on integrated care (i.e., on physician networks) showed that a majority (56%) of them was highly critical on such developments. These physicians believed that physician networks only reduced costs by constraining access to care (and therefore withholding care) or by abetting risk selection, and that physicians in networks are distracted of taking enough time to care for their patients [21]. Another recent survey of doctors in the canton of Geneva showed that many physicians expressed predominantly negative opinions on the impact of managed care tools such as guidelines, gatekeeping, managed care networks, second opinion requirement, pay-for-performance or utilization review. Although they perceived the impacts of these tools to control healthcare costs as positive, the impacts on professional autonomy were valued predominantly negative. Primary care doctors held more positive opinions than doctors in other specialties, whereas psychiatrists were the most critical [22].

Integration beyond primary care and gatekeeping

The fundamental difference between pure gatekeeping systems and integrated care is the dedication of the latter to collaboration over several care levels with upstream and downstream care providers and preferred providers—in other words, vertical integration [9]. Vertical integration is the hallmark of integrated delivery systems as it brings together physician practices, hospitals and other service delivery organisations under the roof of shared values, aligned incentives and agreed accountability. Regarding the 10 key elements for successful integration described earlier, the physician networks in Switzerland may be seen as an early form of integrated care organizations [10].

However, the true importance of integration will become evident in the future in light of the increase in prevalence of chronic diseases and the growing complexity of medical treatment. It will be seen namely at those locations where numerous different treatments and/or types of care have to be approved and coordinated, i.e., in patients with complex chronic diseases and in patients undergoing long-term treatment. In this context intensified integration and/or dedicated coordination and control of treatments promise to optimize the quality of medical treatment, secure the provision of medical care, and increase the economy of care [23].

While chronic disease management initiatives have been developed and implemented in several European countries [24, 25], interest towards chronic disease management initiatives is recent in Switzerland, and only few programs exist [26]. Nevertheless, during past years, initiatives targeting chronic diseases were developed both within and outside physician networks, at regional and/or cantonal levels. In the French-speaking part of Switzerland for example, the implementation of clinical pathways for heart failure and breast cancer patients that do not only include the in-hospital phase of care, chronic disease management programs (e.g. diabetic and heart failure patients) at loco-regional levels, and more recently the political decision to implement a diabetes program in the canton of Vaud, have been taken note of [27]. Other initiatives in the German-speaking region of Switzerland include projects from the Zurich University Institute of Family Medicine, based on the chronic care model and its implementation in the general practice [28–30], as well as other chronic disease management programs developed and proposed by telemedicine support services.

Significance of the Swiss experience

Stronger integration and dedicated collaboration are viewed by most stakeholders within healthcare as the most effective and sustainable package of measures suitable for guaranteeing the high quality and economy of healthcare in the future [31]. The reasoning behind this widespread acceptance is the realization, gained from numerous research projects, that healthcare systems are basically fragmented or simply ‘non-integrated’ because of the contradictory logic espoused by the individual players [32]. The consequences are all too familiar: patient-care processes of low coherency, duplicate treatment tracks, treatment errors, etc. However, another realization is even more important: it is not (only) self-interest and a clinging to power by the individual players that is responsible for fragmentation; rather, fragmentation can be considered a normal state of affairs in the healthcare system. The challenges to be surmounted by any efforts to achieve integration thus become obvious: it is necessary to take account, time and again, of the (unavoidable) fact that the individual players all have a mind of their own and to negotiate intelligent compromises [33].

It is important to note that until now Switzerland had no laws and no political blueprints for integrated care, no statutory framework for physician networks, and no public (start-up) financing for corresponding projects. Physician networks and HMOs were all established solely by initiatives of physicians and health insurance companies. The sole basis for these activities is the healthcare legislation (Swiss Health Insurance Law, KVG) which allows for such initiatives and developments. In other words, when more than half of all primary care providers in Switzerland decided to join physician networks and three out of four of them entered into contracts in which they agree to assume financial co-responsibility, they did so voluntarily. This is important primarily because contractually stipulated integration and financial co-responsibility are diametrically opposed to the traditional professional understanding of physicians [34]. We therefore conclude that the initiation and development of physician networks in Switzerland may be viewed as a model of ‘responsible autonomy’ balancing clinical autonomy and financial accountability [35]. This would argue that—despite the contradictory logic of the individual players—service providers and financing bodies can join forces to develop and implement, on their own initiative, integrated care organisations that frequently extend over large geographical areas.

Future challenges

The future challenges in Switzerland are both to develop physician networks and other chronic disease management initiatives towards more comprehensive integrated care. These developments need to target comprehensive services across the care continuum, standardized care delivery through interprofessional teams, performance management, information systems, governance structure and financial management [10]. Meeting these targets also means modifying practices and attitudes, reorganizing the healthcare system while optimizing and coordinating available resources, and not forgetting to emphasize health promotion and disease prevention.

Reviewers

David Perkins, Director, Centre for Remote Health Research, Broken Hill, Department of Rural Health, University of Sydney; editor-in-chief of the Australian Journal of Rural Health, Australia

Jürgen Wasem, Professor, Institute for Health Care Management and Research, University of Duisburg/Essen, Germany

Volker Amelung, Dr., Professor, Institute for Epidemiology, Social Medicine and Health System Research, Hannover School of Medicine, Hannover, Germany

Contributor Information

Peter Berchtold, College for Management in Healthcare and Forum Managed Care (FMC), Freiburgstrasse 41, CH-3010 Bern, Switzerland.

Isabelle Peytremann-Bridevaux, Healthcare Evaluation Unit, Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine (IUMSP), Centre Hospitalier Vaudois and University of Lausanne, Bugnon 17, CH-1005 Lausanne, Switzerland.

References

- 1.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD reviews of health systems: Switzerland. Paris: OECD; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng TM. Understanding the “Swiss watch” function of Switzerland’s health system. Health Affaires (Millwood) 2010;29:1442–51. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reinhardt UE. The Swiss health system: regulated competition without managed care. Journal of the American Medical Association JAMA. 2004;292:1227–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.10.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.OECD. Health at a glance: Europe 2010. OECD Publishing; 2010. [cited 18 Feb 2011]. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health_glance-2010-en. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kohli R, Bläuer Herrmann A, Babel J. Les scénarios de l’évolution de la population de la Suisse 2005–2050. [Scenarios for demographic development in Switzerland 2005–2050]. Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Office fédéral de la statistique (OFS); 2006. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marques-Vidal P, Cerveira J, Paccaud F, Cornuz F. Smoking trends in Switzerland, 1992–2007: a time for optimism? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2011 Mar;65(3):281–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.099424. [Epub 28 Apr 2010] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marques-Vidal P, Bovet P, Paccaud F, Chiolera A. Changes of overweight and obesity in the adult Swiss population according to educational level, from 1992 to 2007. BMC Public Health. 2010;10 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-87. Feb 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paccaud F, Peytremann-Bridevaux I, Heiniger M, Seematter-Bagnoud L. Vieillissement: éléments pour une politique de santé publique. Un rapport préparé pour le Service de la santé publique du canton de Vaud par l’Institut universitaire de médecine sociale et préventive. [Aging: elements for a public health policy. A report for the health service of the canton Vaud]. Lausanne: Institut universitaire de médecine sociale et preventive; 2006. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kodner D. All together now: A conceptual exploration of integrated care. Healthcare Quarterly. 2009;13:6–11. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2009.21091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suter E, Oelke ND, Adair CE, Armitage Ten key principles for successful health systems integration. Healthcare Quarterly. 2009;13:16–23. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2009.21092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Association Suisse de reseax de medecins. Definition for physician network used by Medswiss. [webpage on the internet]. [cited 18 Feb 2011]. Available from: http://www.medswiss.net. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berchtold P, Peier C, Peier K. Ärztenetze in der Schweiz 2010—auf dem Sprung zu Integrierter Versorgung. [Swiss physician networks 2010—towards integrated care]. Schweizerische Ärztezeitung. 2010;91:1222–4. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swiss Forum Managed Care: Schweizer Ärztenetze. 2010 [Physician network in 2010]. [cited 21 Feb 2011]. Available from: http://www.fmc.ch/infothek/aerztenetzeschweiz/. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berchtold P, Hess K. Evidenz für Managed Care Technical Report 16. [Evidence for Managed Care]. Neuchatel, Switzerland: Swiss Health Observatory; 2006. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Etter JF, Perneger TV. Health care expenditures after introduction of a gatekeeper and global budget in a Swiss health insurance plan. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1998;52:370–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perneger TV, Etter JF, Rougement A. Switching Swiss enrollees from indemnity health insurance to managed care: the effect on health status and satisfaction with care. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:388–93. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.3.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwenkglenks M, Preiswerk G, Lehner R, Weber F, Szucs TD. Economic efficiency of gatekeeping compared with fee for service plans: a Swiss example. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2006;60:24–30. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.038240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Czerwenka W, Metzger K, Fritschi J. Hoher Qualitätsstand in Schweizer Ärztenetzen. [High quality standards in Swiss physician networks]. Ärztezeitung. 2010;91:1856–8. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steurer-Stey C, Frei A, Schmid-Mohler G, Malcolm-Kohler S, Zoller M, Rosemann T. Assessment of Chronic Illness Care with the German version of the ACIC in different primary care settings in Switzerland. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2010;8:122. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Souche A, Chatelain D. Le point de vue de l’association des médecins du canton de Genève par sondage de sa base: Réseaux de soins intégrés. [Integrated care networks from the point of view of the medical association of the canton Geneva]. Bulletin des Médecins Suisse. 2010;46:1811–3. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deom M, Agoritsas T, Bovier PA, Perneger TV. What doctors think about the impact of managed care tools on quality of care, costs, autonomy and relations with patients. BMC Health Services Research. 2010;10:331. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strandberg-Larsen M, Krasnik A. Measurement of integrated healthcare delivery: systematic review of methods and future research directions. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2009 Feb 4;9 doi: 10.5334/ijic.305. Available from: http://www.ijic.org. URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nolte E, McKee M. Caring for people with chronic conditions. A health system perspective. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nolte E, Knai C, McKee M. Managing chronic conditions. Experience in eight countries. Copenhagen: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies and WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peytremann-Bridevaux I, Burnand B. Inventory and perspectives of chronic disease management programs in Switzerland: an exploratory survey. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2009 Oct 7;9 doi: 10.5334/ijic.329. Available from: http://www.ijic.org. URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canton du Vaud. Programme cantonal diabete. [Programme for diabetes]. [webpage on the internet]. [cited 21 Feb 2011]. Available from: http://www.vd.ch/fr/themes/sante-social/services-de-soins/diabete/programme-cantonal. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steurer-Stey C, Frei A, Rosemann T. The chronic care model in Swiss primary care. Revue Medicale de la Suisse. 2010;6:1016–9. [in French] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frei A, Chmiel C, Schläpfer H, Birnbaum B, Held U, Steurer J, et al. The chronic care for diabeteses study (CARAT): a cluster randomized controlled study. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2010;9:23. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-9-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zanoni U, Weber A, Wirthner A, Huber F, Steurer-Stey C. mediX Futuro: für eine zukunftsfähige Hausarztmedizin. [mediX Futuro: towards sustainable primary care]. Schweizerische Ärztezeitung. 2009;37:1414–6. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leape L, Berwick D, Clancy C, Conway J, Gluck P, Guest J, et al. Transforming healthcare: a safety imperative. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2009;18:424–8. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.036954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glouberman S, Mintzberg H. Managing the care of health and the cure of disease—part I: differentiation. Health Care Management Review. 2001;26:56–69. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200101000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Denis J-L, Lamothe L, Langley A. Reforming health care: levers and catalysts for change. In: Casebeer AL, Harrison A, Mark AL, editors. Reforming health care: levers and catalysts for change. Innovations in health care. Basingstoke: Palgrave McMillan; 2006. pp. 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edwards N, Kornacki MJ, Silversin J. Unhappy doctors: what are the causes and what can be done? British Medical Journal. 2002;324:835–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7341.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Degeling P, Maxwell S, Kennedy J, Coyle B. Medicine, management, and modernisation: a “danse macabre”? British Medical Journal. 2003;326:649–52. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7390.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]