Abstract

Introduction

Joint working between health and social care has long been a policy priority in England, with growing interest by the previous New Labour government in achieving ‘joined-up solutions to joined-up problems’.

Policy/practice

Against this background, this paper reviews lessons from current and previous partnership initiatives, summarising some of the key approaches adopted and exploring key underlying concepts and frameworks.

Conclusion

Despite a tendency to focus on structural ‘solutions’, evidence and experience suggests a series of more important processes, approaches and concepts that might help to promote more effective inter-agency working—including a focus on outcomes, consideration of the depth and breadth of relationship required and the need to work together on different levels.

Keywords: health and social care, partnership working

Introduction

In almost every country of the world, there are problems of fragmentation and a lack of continuity in services for frail older people and other groups with complex, multiple needs [1–4]. Almost irrespective of language, culture, structure, context and funding, there are different services responsible for different aspects of service provision and with different financial and regulatory systems, roles and responsibilities, and organisational and professional cultures. Making sense of this in a way that leads to joined-up and well organised experiences for service users and their families is a difficult political, managerial and practice task. Put simply, people do not live their lives according to the categories we create in our welfare services, and any holistic response to health needs will have to link to and be co-ordinated with the responses of other agencies if it is to be successful.

In pursuit of more effective inter-agency working, a number of countries have sought to develop more formal partnerships between local organisations. These tend to share a number of characteristics, such as a focus on a particular at-risk group and a defined catchment area, overall responsibility for arranging and/or delivering comprehensive services, the active involvement of primary care services and a focus on multi-disciplinary teamwork at ground level. Such an approach is a powerful idea and intuitively seems like a sensible way forward. In theory, such integration could lead to more seamless services, user-centred care, an emphasis on prevention and rehabilitation, greater continuity of care, improved access to services, more integrated primary and secondary care and a reduction in inappropriate service use. However, key concerns include the difficulty of combining medical and social models, the practical challenges of working across organisational and professional boundaries, and the risk of acute care (and the high cost of such services) distorting priorities.

There are a range of different models in different countries—each with strengths and limitations. Examples include the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) and Social Health Maintenance Organisations in the US; the SIPA project in Canada; the Rovereto Project in Italy; and Co-ordinated Care Trials in Australia [5]. However, in an English context, partnership working between health and social care is a central feature of government policy and the focus of a significant range of activities at a local level. Although there has long been a recognition of the need for inter-agency collaboration to provide seamless services for users and carers [6, 7], this acquired increasing impetus following the commitment of the previous New Labour government to achieving ‘joined-up solutions’ to ‘joined-up problems’. Responding to the emphasis of central government on partnership working, a large number of different partnership arrangements have been developed in different parts of the country, including Care Trusts, use of the Health Act flexibilities, joint appointments, and the use of staff secondments/joint management arrangements (see below for further discussion). Against this background, this paper reviews the rationales put forward for partnership working, summarises the history of recent partnership initiatives and provides brief discussion of some key theoretical models that managers and practitioners can use to conceptualise and develop working relationships with other agencies. A glossary of key terms and policies is also included at the end of the article for international readers interested in a summary of the English context.

Why work in partnership?

Although there is a substantial and growing literature on partnership working [8–13], there are a number of limitations to our existing knowledge. In particular, much of the current literature is very descriptive and sometimes very ‘faith-based’, emphasising the perceived virtues of partnership working without necessarily citing any evidence for the claims made. Moreover, as a crucial review of the literature suggests, most studies focus on the process of partnership working (how well are services working together?), not on the outcomes of partnerships (do they make a difference to services or to outcomes for users and carers?) [14].

As a result of these shortcomings, many accounts provide long lists of potential benefits, but are less clear about the extent to which these benefits are realisable in practice or about how to achieve such desired outcomes. Thus, the English Audit Commission [15] suggests that partnership working can help to deliver coordinated packages of services to individuals; tackle so-called ‘wicked issues’; reduce the impact of organisational fragmentation (and minimise the impact of any perverse incentives that result from it); bid for or gain access to new resources; align services provided by all partners with the needs of users; make better use of resources; stimulate more creative approaches to problems; and influence the behaviour of the partners or of third parties in ways that none of the partners acting alone could achieve. Similarly, Payne’s work on multi-disciplinary teamwork holds out the hope that effective teams can, in theory, help to bring together key skills; share information; achieve continuity of care; apportion and ensure responsibility and accountability; coordinate the planning of resources; and coordinate in delivering the resources for professionals to apply for the benefit of service users [13]. These are powerful claims, but possibly ones that must be treated with a degree of scepticism—while these proposed benefits seem common sense, achieving them may be more complex than the literature often suggests.

In spite of this, the English Department of Health provides a very strong but very helpful critique of agencies that fail to work in partnership, setting out a clear rationale why services must work together more effectively [16, p. 3]:

All too often when people have complex needs spanning both health and social care good quality services are sacrificed for sterile arguments about boundaries. When this happens people, often the most vulnerable in our society…, and those who care for them find themselves in the no man’s land between health and social services. This is not what people want or need. It places the needs of the organisation above the needs of the people they are there to serve. It is poor organisation, poor practice, poor use of taxpayers’ money—it is unacceptable.

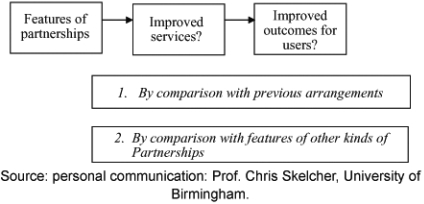

Behind this official pronouncement and behind much of the literature, is a working hypothesis that effective partnerships should lead to better services and better outcomes for service users and their families (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effective partnership working (in theory).

Unfortunately, many of these links currently remain unproved, and further research is required to understand this model in more detail. For example, which approaches to partnership work best for whom in what circumstances? Until such questions receive more definitive answers, however, the Department of Health summary above remains one of the most powerful arguments for working together, even if it is stronger on its critique of the current situation than it is on possible ways forward.

The policy context

In a UK context, the post-war welfare state that was developed in the late 1940s is based on the assumption that it is possible to distinguish between people who are sick (who have ‘health’ needs and receive care free at the point of delivery) and those who are merely frail or disabled (who receive ‘social care’ services that are often means-tested and subject to charges). In addition to this, many wider services (for example, education, policing, social security etc.) have tended to be organised on hierarchical lines, with resources and policy flowing from the centre downwards. More recently, there has been increasing recognition of the need to create links between these different central government functions at a regional and, in particular, at a local level, with more effective inter-agency working for people who have a range of needs. Thus, a disabled person who lives in local authority housing may need adaptations make to their house, have particular transport needs, have particular health and social care support needs, and be keen to access training opportunities in order to gain employment. Similarly, a child at risk of abuse may be living in poor housing in a run-down inner-city area with few social amenities, be in trouble at school, may be at risk of crime (either as a victim of crime or as a perpetrator), and may self-harm or have substance misuse problems (or both). In both these hypothetical scenarios, the person concerned will need a wide range of agencies to work together in a co-ordinated way to meet their needs.

In response to this need to co-ordinate local services more effectively, there have been a number of key policy initiatives. For example, in 1973 the NHS Reorganisation Act placed a statutory duty on health and local authorities to collaborate with each other through Joint Consultative Committees. Advisory rather than executive, these bodies were soon seen to be inadequate for the task in hand [17], prompting calls for further reform. In 1976, these arrangements were strengthened by the creation of joint care planning teams of senior officers and by a joint finance programme to provide short-term funding for social services projects deemed to be beneficial to the health services. Despite growing criticisms of these mechanisms for joint working, formal arrangements for collaboration remained substantially unchanged until the community care reforms of the 1990s [18]. Here, there was an attempt to create a more market-based approach to the delivery of public services, with a purchaser-provider split in health care and the stimulation of a much more mixed economy of provision in adult social care.

Since 1997, the emphasis has arguably been more on creating local networks or partnerships between local agencies. Key policies include:

The Health Act 1999: here, three new legal powers (or ‘flexibilities’) enabled health and social care to create pooled budgets, to develop lead commissioning arrangements or to create integrated providers [19].

The creation of Care Trusts (NHS bodies with social care responsibilities delegated to them). With around 10 such organisations in existence at any one time, this is the closest model to a full merger of health and social care in England [20].

The creation of Children’s Trusts: more virtual in nature than adult Care Trusts, these typically bring together a wider range of partners than just health and social care, and are local authority-based. Alongside these new organisational arrangements, there is also an emphasis on a common assessment framework for children, greater information sharing, a lead professional to co-ordinate care and greater co-location of different professions working with children and young people [21].

Although it is very early days, one emerging option in English health and social care is the piloting of personal health budgets (see [22] for a summary of this policy). Mirroring a system already underway in adult social care, these pilots may allow some patients to receive the cash equivalent of directly provided services, with greater scope for them to spend this money more creatively. If the pilots prove successful, there may be more scope in future for people to integrate their own health and social care bottom up, rather than relying on health and social care policy and organisations to integrate services top down.

However, despite these changes, effective joint working between health and social care seems just as elusive as ever—and the 10th anniversary of the International Journal of Integrated Care seems a good opportunity to reflect on some of the underlying concepts and frameworks that might help to translate policy aspirations into practice. As a result, this paper does not contribute new data or insights per se, but rather seeks to summarise lessons learnt from policy and research into health and social care partnership working in England. At times there is a risk that the frameworks proposed seem a little abstract so we have also tried to reflect briefly on how they have and might be used in practice.

Useful theoretical frameworks

Against this background, there are a number of theoretical frameworks and models available that may help local managers and practitioners to think through their aspirations for local people and the different ways in which they might need to engage partner organisations. These are tools that our organisation—the Health Services Management Centre (HSMC)—uses regularly in its consultancy and development work, and so have we have considerable experience of applying them in practice.

Theories of change

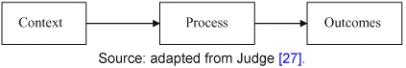

When working with health and social systems around the country, the HSMC often draws on an approach adapted from the ‘theories of change’ literature (utilised, for example, in the national evaluation of Health Action Zones; see Figure 2). In particular, this asks systems to explore:

Figure 2.

Theories of change (adapted).

The outcomes which different stakeholders wish to achieve for service users.

The current context (including both strengths and weaknesses).

Possible ways forward and issues to be resolved.

In particular, HSMC uses this approach to prevent controversial discussion about issues of process and structure from dominating initial inter-agency debate. Instead, this model encourages services to ask themselves the following questions:

Where do we want to be/what do we want to achieve? (outcomes)

Where are we now? (context)

What do we need to do to achieve our desired outcomes? (process)

In our experience, this allows greater time to surface and potentially reconcile different interpretations about desired outcomes and the current context, before moving on to more practical discussions about next steps at a later stage. In particular, it allows managers and practitioners to see partnership working (and any structural changes that may ensue) as a means to an end (of better services and hence better outcomes for users and carers). While partnership working should never be an end in itself, it is easy to see how this happens when an already busy manager is tasked with setting up a new partnership. However well intentioned, it is all too easy to lose sight of why the partnership was so important in the first place and the outcomes it was meant to deliver. Instead, having the partnership becomes the main aim. In contrast, ‘theories of change’ encourages a difficult but helpful focus on outcomes. As an example, use of this framework with one local health and social care community enabled the senior managers and clinicians taking part to start articulating to each other what they were trying to achieve for local people, why they felt that collaboration was the best way forward and why they had chosen a particular form of collaboration. Prior to using this framework, such assumptions and drivers had only ever been implicit, and the local area had been unable to develop a shared vision of what it was trying to achieve and why.

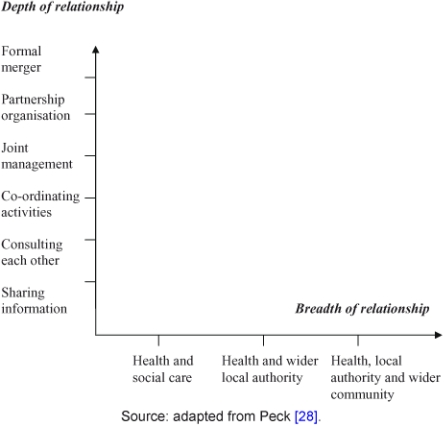

Depth v breadth of partnership

Having clarified desired outcomes and the strengths and limitations of the current context, there is scope for individual organisations to reflect in more detail on the partners they need to engage and the way in which they might need to work with different partners. Depending on desired outcomes, there may need to be very different organisations involved, and a range of options exist with regard to the depth and breadth of partnership that may be appropriate. This is set out in Figure 3, and it may be helpful for local services to map existing partnerships onto this graph in order to reflect on current relationships and their fitness for purpose. Indeed, some of the areas with which we have worked have tried to use this matrix as a way of illustrating the relationships and collaborations they currently have, and to overlay a map of the relationship they think they need in order to be genuinely successful—thus giving a visual sense of the task in hand and the direction of travel required.

Figure 3.

Depth v breadth.

Different levels of partnership working

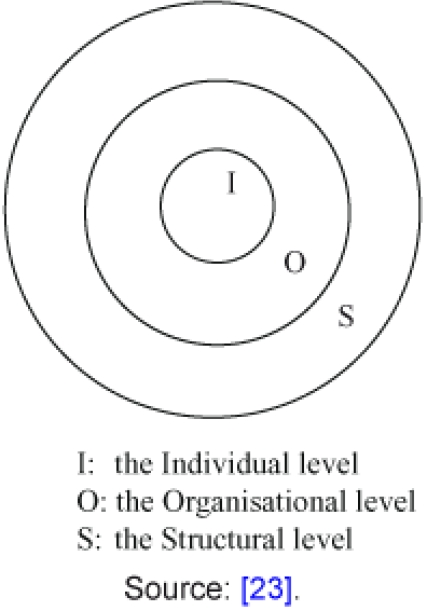

In addition, Glasby’s research into delayed hospital discharges [23] identifies three different levels of activity which health and social care agencies need to address in order to develop effective partnerships (see Figure 4): individual (I), organisational (O) and structural (S). While there is much more that can be done to encourage joint working between individual practitioners and local health and social care organisations (the I and O levels), Glasby argues that more action is required at a central government level to tackle some of the legal, administrative and bureaucratic barriers to partnership working. These are deeply engrained in our current service structures and, ultimately, derive from the fact that the current health and social care system is based on an underlying division between two very different organisations with different priorities, values and ways of working. The framework is presented in terms of a series of inter-locking circles, as each level of activity has the capacity to influence or be reinforced by the others. Thus, the way in which individuals behave is based in part on the norms, values and policies of their organisations, which in turn are shaped by a series of structural barriers to partnership working at a central government level. Similarly, these structural barriers depend in part on the characteristics of particular types of health and social care organisation, which depend ultimately on the people working in these organisations. As a result, any policy designed to achieve true partnership working will need to operate at all three levels of activity at the same time if it is to be successful. While this is more helpful for policy makers than practitioners, we have previously used this framework when working with national policy makers so that future policy tries to focus on different levels of partnership working in a more nuanced way.

Figure 4.

Different levels of partnership working.

Key factors that may help or hinder partnership working

Although focusing on outcomes can be difficult, there is a large and growing body of evidence with regard to process. Over time, a series of consistent messages has emerged from various studies about the underlying factors and local conditions that may assist or hamper attempts to work together across organisational boundaries. Two of the most prominent frameworks are set out in Boxes 1 and 2 and there is scope to use these in conjunction with external facilitation to explore shared understandings of progress to date, outstanding barriers, mutual perceptions of current partnerships, and the ‘readiness’ of local services for new ways of joint working. The Partnership Assessment Tool in particular contains a scoring mechanism and this can be used to explore views of local relationships, identifying areas for celebration and areas for further work.

Box 1 Partnership working: what helps and what hinders?

Barriers:

Structural (the fragmentation of service responsibilities across and within agency boundaries).

Procedural (differences in planning and budget cycles).

Financial (differences in funding mechanisms and resource flows).

Professional (differences in ideologies, values and professional interests).

Perceived threats to status, autonomy and legitimacy.

Principles for strengthening strategic approaches to collaboration:

Shared Vision: Specifying what is to be achieved in terms of user-centred goals, clarifying the purpose of collaboration as a mechanism for achieving such goals, and mobilising commitment around goals, outcomes and mechanisms.

Clarity of Roles and Responsibilities: Specifying and agreeing ‘who does what’, and designing organisational arrangements by which roles and responsibilities are to be fulfilled.

Appropriate Incentives and Rewards: Promoting organisational behaviour consistent with agreed goals and responsibilities, and harnessing organisational self-interest to collective goals.

Accountability for Joint Working: Monitoring achievements in relation to the stated vision, holding individuals and agencies to account for the fulfilment of pre-determined roles and responsibilities, and providing feedback and review of vision, responsibilities, incentives, and their inter-relationship.

Source: [18]

Box 2 The Partnership Readiness Framework.

Building shared values and principles.

Agreeing specific policy shifts.

Being prepared to explore new service options.

Determining agreed boundaries.

Agreeing respective roles with regard to commissioning, purchasing and providing.

Identifying agreed resource pools.

Ensuring effective leadership.

Providing sufficient development capacity.

Developing and sustaining good personal relationships.

Paying specific attention to mutual trust and attitude.

Source: [29]

The limits of structural change

In addition to factors that help the development of partnerships, there is a growing literature on what does not help and, in particular, on the limits of structural change. This material is summarised in detail elsewhere, but the emerging evidence [24, 25] suggests that:

Structural change by itself rarely achieves stated objectives.

Mergers typically do not save money—the economic benefits are often modest at best and are more than offset by unintended negative consequences, such as a potential reduction in productivity and morale.

Mergers are potentially very disruptive for managers, staff and service users, and can give a false impression of change.

Mergers can stall positive service development for at least 18 months.

Instead, research suggests that successful mergers may depend upon [24]:

Clarifying the real (as opposed to the stated) reasons behind the merger.

Resourcing adequate organisational development support.

Matching activities closely to intentions to reduce cynicism among key staff groups whose support will be crucial in realising the intended benefits.

A more detailed discussion of partnership working and organisational culture is available from the Integrated Care Network [26]. Unfortunately, all the available evidence suggests that lessons from research are not heeded in practice when debating future reforms—and a new government is embarking on one of the largest structural reorganisations in the history of the NHS as this article is being written. Indeed, the political popularity of the NHS is such that successive Ministers and governments have often looked to major structural change (typically every 3 years or so) as a solution, perhaps tempted by the false impression it gives of bold, decisive action, sweeping away the old and bringing in the new. In practice, experience over time suggests that such frequent changes tend to make staff even more change resistant and make genuine service improvement even harder in the short-term.

Conclusion

On the eve of the 10th anniversary of the International Journal of Integrated Care, experience in England suggests a number of key lessons with regards to partnership working between health and social care. However services have been organised in the past, it has become increasingly clear that people do not live their lives according to the categories created in our welfare systems—and some form of joint working is essential if we are to find meaningful ways of joining up services in order to meet complex needs more fully. Although partnership working remains a key government priority in England, evidence over time suggests that some of the structural ‘solutions’ that sometimes seem so tempting may not actually be the answer (by themselves). Instead, the English experience suggests a number of underlying concepts, theoretical models and frameworks that may help local partners to be clearer about the outcomes they are trying to achieve, the partners they need to engage, the relationships they need to develop and the common factors that help or hinder joint working. At the time of writing, England has a new government committed to reducing state expenditure and public sector debt, as well as a challenging international economic climate. As the government gets to work and the cuts bite, the task for health and social care will be to hold on to some of the lessons of previous reforms in a difficult political and economic context. Above all, they will need to realise that health and social care have to work together to support people with complex needs, and that cuts in spending make joint working even harder but even more important.

Acknowledgments

This article has been written to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the International Journal of Integrated Care. It is based on a book chapter originally published in Kieran Walshe and Judith Smith’s (eds.) 2006 book on Healthcare management (1st ed.). This chapter has been edited and re-written for current purposes, and the material is reproduced with the kind permission of Open University Press. All rights reserved. See: Glasby, J. (2006) Managing in partnership with other agencies, in K. Walshe and J. Smith (eds.) Healthcare management. Maidenhead, Open University Press.

Brief glossary

Care Trusts: a new form of NHS organisation integrating health and social care, set up from 2002 onwards. Because of the level of structural change involved, there were only ever about 10 Care Trusts at any one time (out of 150 health and social care communities).

Children’s Trust: following a high profile child death, local health, social care and education services were tasked with creating more integrated children’s services, with a single Director of Children’s Services. This led to the creation of a Children’s Trust (a more integrated structure for children’s services, but with the exact model and level of integration varying from area to area).

Community care reforms (1990–1993): legislation to make local councils responsible for funding long-term care for older people. This included a rebadging of social workers as ‘care managers’ responsible for assessing people in need and designing care packages.

Health Act/Health Act flexibilities: legislation passed initially in 1999 to enable local health and social care partners to pool aspects of their budgets, nominate one another as a lead commissioner for particular client groups or create integrated provider organisations.

Health Action Zones: created by the previous New Labour government to provide additional funding for deprived communities to develop new cross-cutting approaches to tackling health inequalities.

Integrated Care Network: government network promoting good practice around joint working and integration.

Local government: locally elected councils responsible for adult social care (as well as services such as children’s services, roads, housing, economic development etc).

National Health Service (NHS): national system for providing health care, typically free at the point of delivery.

Personal budgets/personal health budgets: new form of more individualised funding, beginning in adult social care but now being piloted in health care. After an assessment (often a supported self-assessment) the person is given an indication of how much money is available to spend and given greater choice over how this resource is spent.

Contributor Information

Jon Glasby, Health Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham, Park House, 40 Edgbaston Park Road, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2RT, UK

Helen Dickinson, Health Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham, Park House, 40 Edgbaston Park Road, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2RT, UK.

Robin Miller, Health Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham, Park House, 40 Edgbaston Park Road, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2RT, UK.

Reviewers

Jill Manthorpe, Professor of Social Work, Director of the Social Care Workforce Research Unit, King’s College London, UK

Peter Alleback, Professor in Social Medicine, Karolinska Institutut SE-171 77 Stockholm, Sweden

One anonymous reviewer

References

- 1.Glasby J, Dickinson H, editors. International perspectives on health and social care. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banks P. Policy framework for integrated care for older people. London: King’s: Fund/CARMEN Network; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nies H, Berman PC. Integrating services for older people: a resource book for managers. Dublin: European Health Management Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leichsenring K, Alaszewski A, editors. Providing integrated health and social care for older persons: a European overview of issues at stake. Aldershot: Ashgate; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kodner D, Kay Kyriacou C. Fully integrated care for frail elderly: two American models. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2000 Nov 1; 1 [cited 2004 Feb 25]. Available from http://www.ijic.org/ URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Glasby J, Littlechild R. The health and social care divide: the experiences of older people. 2nd ed. Bristol: Policy Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Means R, Smith R. From poor law to community care. Basingstoke: Macmillan; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrett G, Sellman D, Thomas J, editors. Interprofessional working in health and social care. Basingstoke: Macmillan; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glendinning C, Powell M, Rummery K. Partnerships, New Labour and the governance of welfare. Bristol: Policy Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammick M, Freeth D, Copperman J, Goodsman D. Being interprofessional. Cambridge: Polity Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glasby J, Dickinson H. Partnership working in health and social care. Bristol: Policy Press; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sullivan H, Skelcher C. Working across boundaries: collaboration in public services. Basingstoke: Palgrave; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Payne M. Teamwork in mutliprofessional care. Basingstoke: Macmillan; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dowling B, Powell M, Glendinning C. Conceptualising successful partnerships. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2004;12(4):309–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2004.00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Audit Commission . A fruitful partnership: effective partnership working. London: Audit Commission; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Health Partnership in action: new opportunities for joint working between health and social services—a discussion document. London: Department of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wistow G, Fuller S. Joint planning in perspective. Birmingham: Centre for Research in Social Policy and National Association of Health Authorities; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hudson B, Hardy B, Henwood M, Wistow G. Inter-agency collaboration final report. Leeds: Nuffield Institute for Health; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glendinning C, Hudson B, Hardy B, Young R. National evaluation of notifications for the use of the Section 31 partnership flexibilities in the Health Act 1999: final project report. Leeds/Manchester: Nuffield Institute for Health/National Primary Care Research and Development Centre; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glasby J, Peck E, editors. Care trusts: partnership working in action. Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Her Majesty’s Treasury. Every child matters. London: The Stationary Ofice; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glasby J, Littlechild R. Direct payments and personal budgets. Bristol: The Policy Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glasby J. Hospital discharge: integrating health and social care. Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peck E, Freeman T. Reconfiguring PCTs: influences and options. Briefing paper prepared for the National Health Services Alliance. Birmingham: Health Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Social Services Inspectorate/Audit Commission. Old virtues, new virtues: an overview of the changes in social care services over the seven years of Joint Reviews in England, 1996–2003. London: Social SI/Audit Commission; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peck E, Crawford A. ‘Culture’ in partnerships: what do we mean by it and what can we do about it? Leeds: Integrated Care Network; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Judge K. Testing evaluation to the limits: the case of English Health Action Zones. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2000;5(1):3–5. doi: 10.1177/135581960000500102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peck E. Integrating health and social care. Managing Community Care. 2002;10(3):16–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poxton R. What makes effective partnerships between health and social care? In: Glasby J, Peck E, editors. Care trusts: partnership working in action. Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]