Abstract

We present a dynamical model incorporating both physiological and psychological factors that predicts changes in body mass and composition during the course of a behavioral intervention for weight loss. The model consists of a three-compartment energy balance integrated with a mechanistic psychological model inspired by the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). The latter describes how important variables in a behavioural intervention can influence healthy eating habits and increased physical activity over time. The novelty of the approach lies in representing the behavioural intervention as a dynamical system, and the integration of the psychological and energy balance models. Two simulation scenarios are presented that illustrate how the model can improve the understanding of how changes in intervention components and participant differences affect outcomes. Consequently, the model can be used to inform behavioural scientists in the design of optimised interventions for weight loss and body composition change.

Keywords: behavioural interventions, weight loss, obesity, body composition, energy balance, Theory of Planned Behavior, dynamical systems

1. Introduction

Obesity rates in the United States have increased substantially in recent decades [1]. In 2000, the percentage of adults in the US with Body Mass Index (BMI) exceeding 30 was 19.8% [2]. The 2000 census reported that 27% of US adults do not engage in any physical activity, and only 24.4% of US adults consumed at least five servings of fruits and vegetables a day. Among US adults participating in programs for losing or maintaining weight, only 17.5% were following recommended guidelines for reducing calories and increasing physical activity [2]. More recently, the World Health Organisation has revealed that 2.7 and 1.9 million deaths per year are attributable to low fruit and vegetable intake and low physical activity, respectively [3]. Unhealthy diet behaviours are responsible for 31% of the cases of ischemic heart disease, 11% of the cases of stroke and 19% of the cases of gastrointestinal cancer.

Because obesity represents a preventable cause of premature morbidity and mortality, much research activity has been devoted to understanding its causes, and a number of diverse solutions have been proposed. Some of these have major disadvantages; for instance, bariatric surgery and very low-calorie diets usually lead to a loss of primarily fat-free mass, which in turn causes a temporary decrease on energy requirements and in the long run a possible regain of the weight lost [4, 5]. Solutions leading to permanent weight loss require sustained lifestyle changes in an individual; consequently, developing optimised behavioural interventions that promote healthy eating habits and increased physical activity represents a problem of both fundamental and practical importance.

The primary goal of this paper is to improve the understanding of behavioural weight change interventions by expressing these as dynamical systems. Dynamic modelling considers how important system variables (e.g., intervention outcomes) respond to changes in input variables (e.g., intervention dosages, exogeneous influences) over time. A dynamical model can be used to answer questions regarding what variables to measure, how often, and the speed and functional form of the outcome responses as a result of decisions regarding the timing, spacing, and dosage levels of intervention components. A dynamical systems approach has been proposed in the analysis of novel behavioural interventions, for instance, adaptive interventions for behavioural health [6].

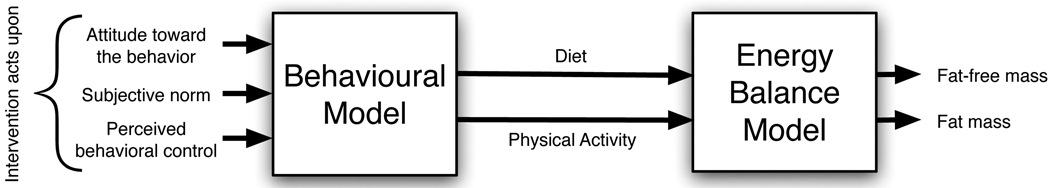

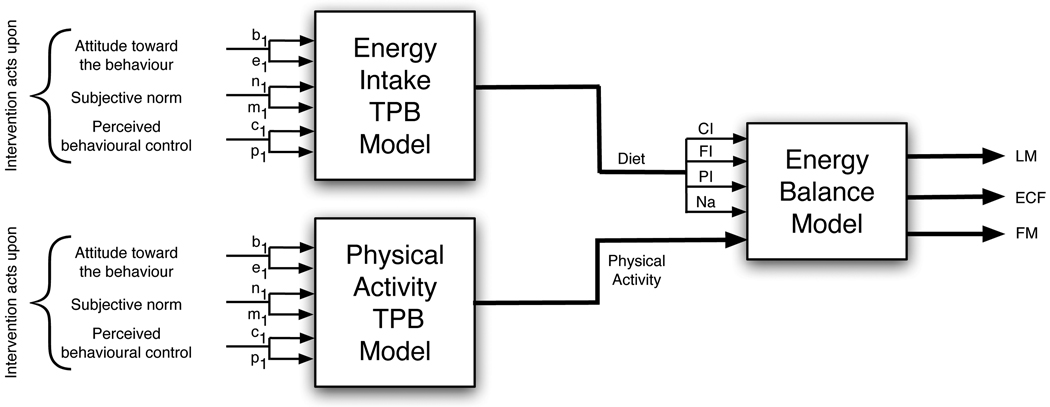

To achieve this goal, we develop in this paper a dynamical model for daily weight change incorporating both physiological and psychological considerations. For the physiological component, we rely on the concept of energy balance to obtain a model that describes the net effect of energy intake from food minus energy consumption, the latter including physical activity. This model can be used to determine the reduction in caloric intake and the level of physical activity that are necessary to achieve a desired weight loss goal. For the psychological component, we present a model for the dynamics of diet and exercise behaviour. This model explains how intentions, subjective norms, attitudes, and other system variables that may be impacted by an intervention can result in healthy eating habits and increased physical activity over time. A model based on the widely-accepted Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB; [7]) is used for this purpose. Figure 1 shows the general conceptual diagram for the integrated dynamical model philosophy developed in this paper.

Figure 1.

General diagram of the dynamical model for body mass and composition change.

The paper is organised as follows: Section 2 presents the energy balance model. Section 3 gives a brief description of the TPB and presents a mechanistic dynamical model for the TPB based on fluid analogies. Section 4 describes two representative simulations of the dynamical model and discusses the role and importance of some of the parameters in the model. Finally, Section 5 summarises our main conclusions and discusses areas of current and further study.

2. Energy Balance Model

The functional relationship between energy balance and weight change has been studied extensively in the literature [8–18]. In this section the goal is to develop a simple yet informative input-output energy balance model that will serve as the basis for describing how weight varies as a result of changes in diet and physical activity. First, we present the basic dynamics governing energy balance using a conventional two-compartment model; this is followed by a more complete three-compartment model. The three-compartment model is validated using data from the Minnesota Semi-Starvation Experiment [19].

2.1. Basic Dynamics and Two-Compartment Model

The normal daily energy balance EB(t) is described as follows:

| (1) |

where EI(t) is the energy intake and EE(t) is the energy expenditure at day t. The daily energy intake EI, expressed in kilocalories (kcal), can be modelled based on the daily energy requirements and dietary reference intakes [20, 21]. However, for simplicity we model EI using the Atwater methods of energy calculation resulting from carbohydrate intake (CI), fat intake (FI), and protein intake (PI), all expressed in units of grams/day [22, 23]:

| (2) |

where a1 = 4 kcal/gram, a2 = 9 kcal/gram, and a3 = 4 kcal/gram.

The daily energy expenditure EE, expressed in kcal, is calculated as follows:

| (3) |

where the thermic effect of feeding TEF(t) denotes the energy expended in processing food, PA(t) is the energy spent as a result of physical activity and RMR(t) is the resting metabolic rate. The energy expended on TEF usually ranges from 7 to 15% of the total energy intake. The thermic effect of exercise PA, expressed in kcal, captures the energy consumed as a result of conducting work activities, household tasks, and physical exercise. The RMR refers to the energy needed to maintain basic physiological processes, and is best assessed in an overnight fasted state. The RMR represents a substantial percentage (45–70%) of energy expenditure for the typical individual [20].

In the two-compartment model, the total body mass BM is given by the sum of two compartments corresponding to fat mass FM and fat-free mass FFM:

| (4) |

The daily energy balance in Equation 1 is partitioned into one of these two compartments, each described by its own differential equation,

| (5) |

| (6) |

ρFM = 9400 kcal/kg and ρFFM = 1800 kcal/kg are energy densities, while p(t) is the p-ratio. The p-ratio is the parameter that assigns a percentage of the imbalance denoted by EB to the compartments fat mass and fat-free mass, respectively [24]. The work of Westerterp et al. [10] and Chow and Hall [14] are illustrations of two-compartment energy balance models. Hall [25] was the first to define p as given by the Forbes formula [26]:

| (7) |

2.2. Three-Compartment Model

2.2.1. Model dynamics

Recent work by Hall and Chow [5, 13, 14, 17, 18] enables the traditional two-compartment model to be extended into a three compartment model in which fat-free mass is further divided into lean mass (LM) and extra-cellular fluid (ECF). The total body mass is given by the sum of these three compartments

| (8) |

Each of these is defined by its own differential equation:

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

The lean mass energy density ρLM is equivalent to ρFFM = ρLM = 1800 kcal/kg. Likewise, p is given as in (7), but with C determined on the basis of the lean mass

| (12) |

For the extra-cellular fluid per (11), ΔNadiet is the change on sodium in mg/d, CIb is the baseline carbohydrate intake, [Na] = 3.22 mg/ml, ξNa = 3 mg/ml/d, and ξCI = 4000 mg/d. ρw is the density of water, which we consider throughout as 1 kg/liter (1 mg/ml).

The general expression for energy expenditure EE in Equation 3 is modelled explicitly as follows:

| (13) |

β = 0.24 is the coefficient for the thermic effect of feeding TEF. δ, the physical activity coefficient, is expressed in terms of kcal per kg of body mass. γLM = 22 kcal/kg/d, γFM = 3.2 kcal/kg/d, ηFM = 180 kcal/kg and ηLM = 230 kcal/kg are coefficients for the calculation of the resting metabolic rate RMR. The constant K accounts for initial conditions and is determined by solving Equation 1 assuming an initial steady-state ( by definition of steady-state):

| (14) |

The steady-state is denoted by a bar over any time-dependent variable. By substituting (9) and (10) in (13), it becomes possible to obtain a closed-form expression for energy expenditure without the need for derivatives of FM and LM:

| (15) |

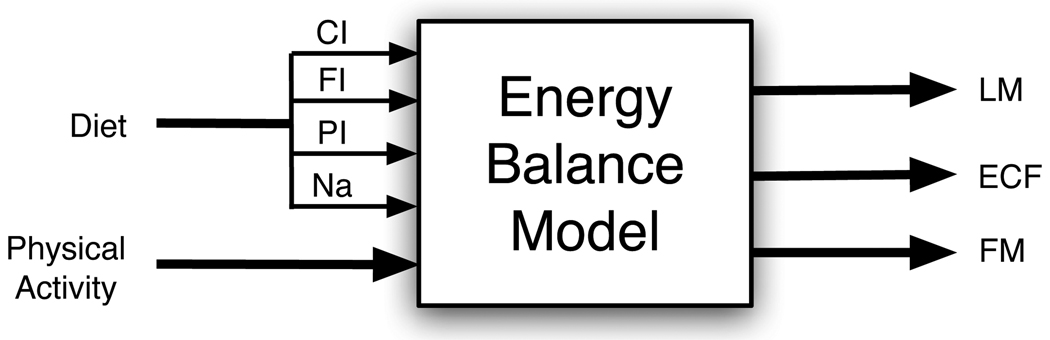

In summary, the three-compartment dynamical model consists of CI, FI, PI, ΔNadiet, and δ as inputs, and FM, LM, and ECF as outputs whose sum corresponds to the total body mass BM. A block diagram is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Input-output block diagram representation for the three-compartment energy balance model. Primary inputs to the model consist of physical activity and diet. Diet in turn is comprised of carbohydrate intake (CI), fat intake (FI), protein intake (PI) and sodium intake (Na); the output compartments consist of lean mass (LM), fat mass (FM), and extracellular fluid (ECF).

2.2.2. Initialisation

Initial conditions for each of the compartments may be known experimentally; if that is not the case, these can be estimated based on various correlations available in the literature. For example, one can compute the initial lean mass LM using the regression formulas from Westerterp et al. [10]:

| (16) |

| (17) |

The initial fat mass FM can be estimated from the regression equations from Jackson et al. [27]:

| (18) |

| (19) |

The latter equations require knowledge of the initial body mass BM and body mass index BMI, which is determined from

| (20) |

To determine the initial ECF, we use the regression equations of Silva et al. [28] for men and women, respectively:

| (21) |

| (22) |

Silva et al. [28] note that ECF was strongly affected by weight and height in both males and females; age, however, made significant contributions to the models for males, but not for females.

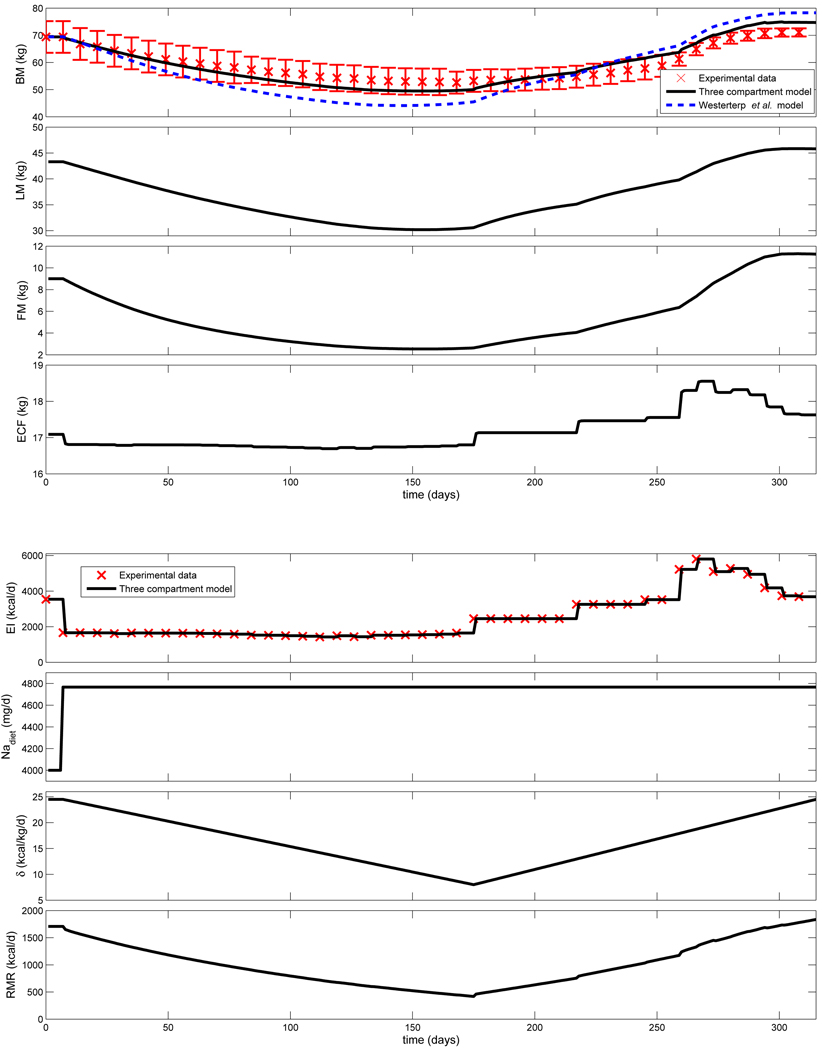

2.2.3. Validation with the Minnesota Semi-Starvation Experiment

A well-known experimental study in which daily weight change, diet, and activity were tracked for a group of participants is the Minnesota Semi-Starvation Experiment [19]. The goal of this study was to determine the physiological and psychological effects of weight loss and weight gain diets on human beings. The experiment was performed on 32 healthy men with the following average characteristics: age=25.5 y, height=1.63 m, BM = 69.39 kg and FM = 9.0 kg. Various researchers have compared mechanistic models against this experiment, showing good agreement [13, 29]. Table 1 summarizes the time line and diets applied to the participants during the experiment.

Table 1.

Time line and diets of the Minnesota Semi-Starvation Experiment.

| Time line | Diet |

|---|---|

| Control diet (12 weeks) | Average basic diet provided 3492 kcal/d: PI =112gm, FI =124gm and CHO=482. |

| Semi-starvation diet (24 weeks) | Average daily intake was 1570 kcal/d: PI=50 gm, FI=30 gm, CI=275 gm. |

| Rehabilitation average intake (12 weeks restricted + 8 weeks unrestricted) |

1–6th week = 2449 kcal/d. 7–10th week=3257 kcal/d. 11–12th week=3518 kcal/d. 13–20th week=3200–4500 kcal/d. |

Based on the average characteristics of the participants, we used Equation 22 to determine the initial ECF (17.09 kg) and Equation 8 to find the initial LM (43.29 kg). For calculating ECF, we assume a pre-intervention sodium intake of 4000 mg/d that comprises a typical diet. The Minnesota experiment reports that the average salt intake during the trial consisted of 12.12 g of NaCl; given that NaCl consists of 39.337% Na, this implies a sodium intake of 4767 mg/day, resulting in ΔNadiet = 767 mg/d as an input to the model. This change is kept constant throughout the period of the trial.

Physical activity during the Minnesota experiment consisted of: approximately 15 hours per week working in either maintenance of the laboratory and living quarters, laundry, laboratory assistance, shop duties or clerical and statistical work; walking outdoors 22 miles per week; spending a half-hour per week on a motor-driven treadmill at 3.5 miles per hour on a 10 per cent grade; and walking two to three miles per day to and from the dining hall. Hall [13] interprets the report in Keys et al. [19] of an observed decrease in physical activity and a reduced “activity drive” during the semi-starvation period to signify that the PA coefficient δ should decrease with time during the period of starvation, then increase as refeeding takes place. To this effect, Hall et al. [5] consider a maximum value of δ = 24.5 kcal/kg/d and a minimum value of δ = 8 kcal/kg/d during the course of the experiment; we rely on these values in defining the input profile for δ in our model.

Figure 3 compares the results of the proposed three-compartment model with the experimental data and the two compartment model of Westerterp et al. [10]. Changes in EI summarized in Table 1 as well as the changes in δ and Nadiet previously reported serve as inputs to the energy balance model. Figure 3 shows a good agreement between the average body weight of the participants in the Minnesota experiment against the three-compartment simulation result through the duration of the study. The three-compartment model displays a superior fit compared to the model from Westerterp et al. [10].

Figure 3.

Body mass BM and compartments (lean mass LM, fat mass FM, and extra-cellular fluid ECF) obtained from the three compartment model for the Minnesota semi-starvation experiment [19]. Body mass is compared to experimental data (★, with error bars) and the total body mass from the Westerterp et al. [10] two-compartment model (dashed line).

Additional analysis and simulation results on the Minnesota experiment, including subgroup results during the rehabilitation phase, can be found in the technical report by Navarro-Barrientos and Rivera [30]. The energy balance model can be evaluated interactively using the software package Weigh-IT developed in the ASU-Control Systems Engineering Laboratory (http://csel.asu.edu/Weigh-IT).

3. Behavioural Model

In addition to capturing the dynamics of energy balance, our approach requires modelling the psychology of diet and exercise behaviour in human beings. In this section a relevant psychological theory (the Theory of Planned Behavior) is extended into a dynamical systems representation that can be integrated with the energy balance model to provide a comprehensive behavioural intervention model. A mechanistic modeling framework relying on a fluid analogy, and patterned after concepts in inventory management in supply chains will be used for this purpose.

3.1. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

For almost two decades, the TPB [7] has been used extensively within the social sciences for describing the relationship between behaviours, intentions, attitudes, norms, and perceived control. Many studies have relied on the TPB and its forerunner, the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) [31] to describe mechanisms of behaviour in diverse application settings; these include healthy eating habits [32] and exercise [33–35]. In the TPB framework, intention is an indication of the readiness of a person to perform a given behaviour, while behaviour is an observable response in a given situation with respect to a given target. Intention is influenced by the following components:

Attitude Toward the Behavior: This is the degree to which performing the behavior is positively or negatively valued. It is determined by the strength of beliefs about the outcome and the evaluation of the outcome.

Subjective Norm: This is the perceived social pressure to engage or not engage in a behavior. It is determined by the strength of the beliefs about what people want the person to do, also called normative beliefs, and the desire to please people, also called motivation to comply.

Perceived Behavioral Control: This reflects the perception of the ability to perform a given behavior, i.e. the beliefs about the presence of factors that may facilitate or impede performance of the behavior. It is determined by the strength of each control belief and the perceived power of the control factor.

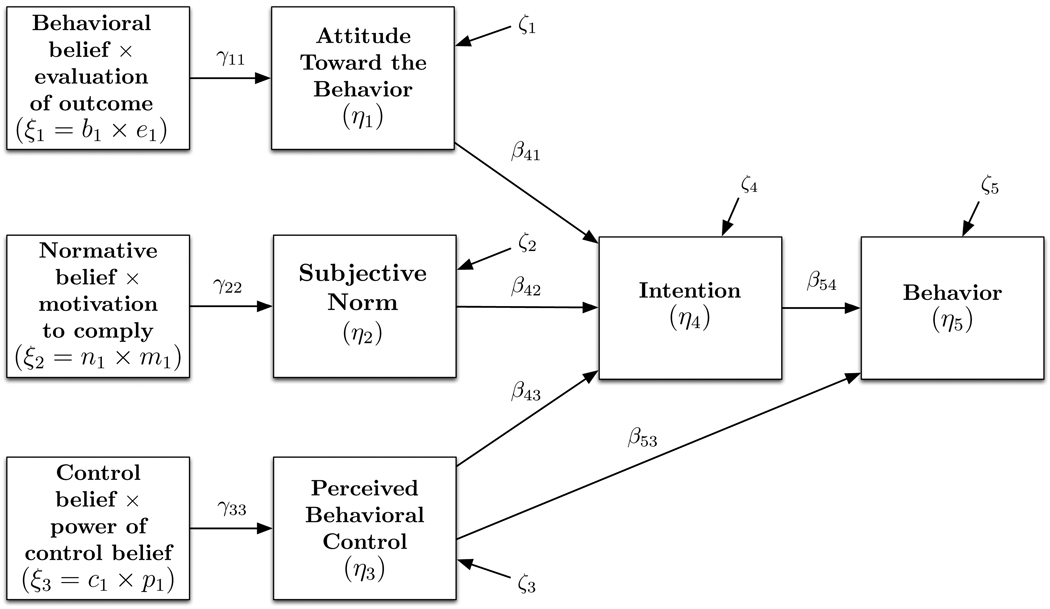

A standard mathematical representation for TPB relies on Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) [36]. The field of SEM is substantial, but in this work we limit ourselves to a special case of SEM called path analysis. The main characteristics of path analysis models is that they do not contain latent variables, i.e., all problem variables are observed, and the independent variables are assumed to have no measurement error [37]. The TPB represented as a path analysis model with a vector η of endogenous variables and a vector ξ of exogenous variables is expressed as follows:

| (23) |

| (24) |

where B and Γ are matrices of βij and γij regression weights, respectively, and ζ is a vector of disturbance variables. Figure 4 shows the intention-behavior TPB path analysis model for Equation 24. Typically, the principles of TPB assume that the attitude toward the behavior η1, the subjective norms η2 and the perceived behavioral control η3 are estimated using the expectancy-value model, which considers the sum over the person’s behavioral beliefs, normative beliefs and control beliefs, respectively, that are accessible at the time. However, for simplicity and without loss of generality, we consider only one exogenous variable per compartment. Thus,

| (25) |

| (26) |

| (27) |

Figure 4.

Path diagram for the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) with three exogenous variables ξi, five endogenous variables ηi, regression weights γij and βij and disturbances ζi.

The exogeneous variables ξ1, ξ2, and ξ3 and their subcomponents form the basis for the inputs of a dynamical model for the TPB; this is explained in more detail in the ensuing subsection.

3.2. Dynamic Fluid Analogy for the TPB

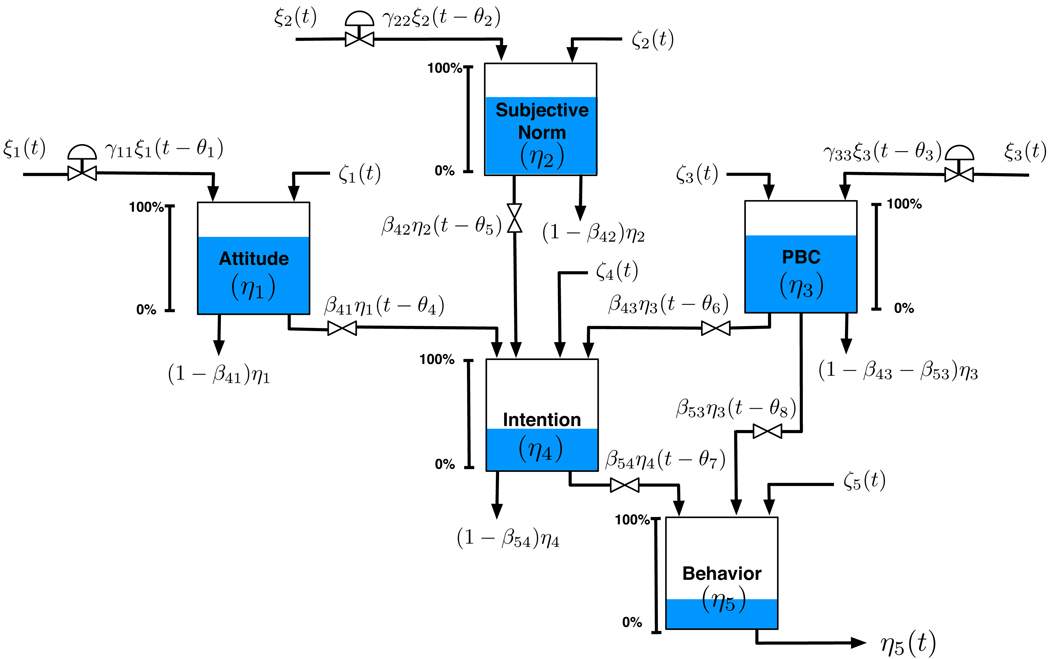

The classical SEM-TPB model, as expressed in Equation 23, represents a static (i.e., steady-state) system that does not capture any changing behaviour over time. In order to expand the TPB model to include dynamic effects, we propose the use of a fluid analogy which parallels the problem of inventory management in supply chains [38]. This analogy is expressed diagrammatically in Figure 5. We consider a dynamic fluid analogy of TPB with five inventories: attitude η1, subjective norm η2, perceived behavioral control η3, intention η4 and behavior η5. Each inventory is replenished by inflow streams and depleted by outflow streams. The path diagram model coefficients γ11, ⋯, γ33 are the inflow resistances and β41, ⋯, β54 are the outflow resistances, which can be physically interpreted as those fractions of the inventories of the system that serve as inflows to the subsequent layer in the path analysis model.

Figure 5.

Fluid analogy for the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) corresponding to the path diagram depicted in Figure 4. PBC stands for perceived behavioral control.

To generate the dynamical system description we apply the principle of conservation of mass to each inventory, where accumulation corresponds to the net difference between the mass inflows and outflows:

| (28) |

Relying on the rate form for equation (28) leads to a system of differential equations according to:

| (29) |

| (30) |

| (31) |

| (32) |

| (33) |

where ξ1(t) = b1(t)e1(t), ξ2(t) = n1(t)m1(t), ξ3(t) = c1(t)p1(t) according to Equations 25–27, and ζ1, ⋯, ζ5 are zero-mean stochastic signals. The dynamical system representation according to Equations 29 through 33 includes all the SEM model parameters and is enhanced by the presence of time delays θ1, .., θ8 that model transportation lags betweens the inflows and outflows, and time constants τ1, .., τ5 that capture the capacity of the tanks for each inventory in the system, and allow for exponential decay (or growth) in the system variables. These parameters can be used to determine the speed at which an intervention participant or population can transition between values for η1, .., η5 as a result of changes in ξ1, ξ2, and ξ3. A number of important points of interest are summarised below:

At steady-state, i.e., when , Equations 29 through 33 reduce to the SEM model according to (23) without approximation.

The SEM model coefficients γij and βij correspond directly to gains in the dynamical system.

- Because the PBC inventory feeds both the downstream intention and behavior inventories, the outflow resistances from PBC are subject to the constraint:

(34) - The initial level of the inventories, which are determined by finding the solution to the system of Equations 29–33 at steady state, correspond to:

(35) (36) (37) (38) (39) The dynamical model description does not require (or assume) a single subject interpretation. The SEM model is naturally estimated cross-sectionally from data obtained from a population; the dynamical model can be estimated with respect to a population as well, but will require availability of repeated measurements over time.

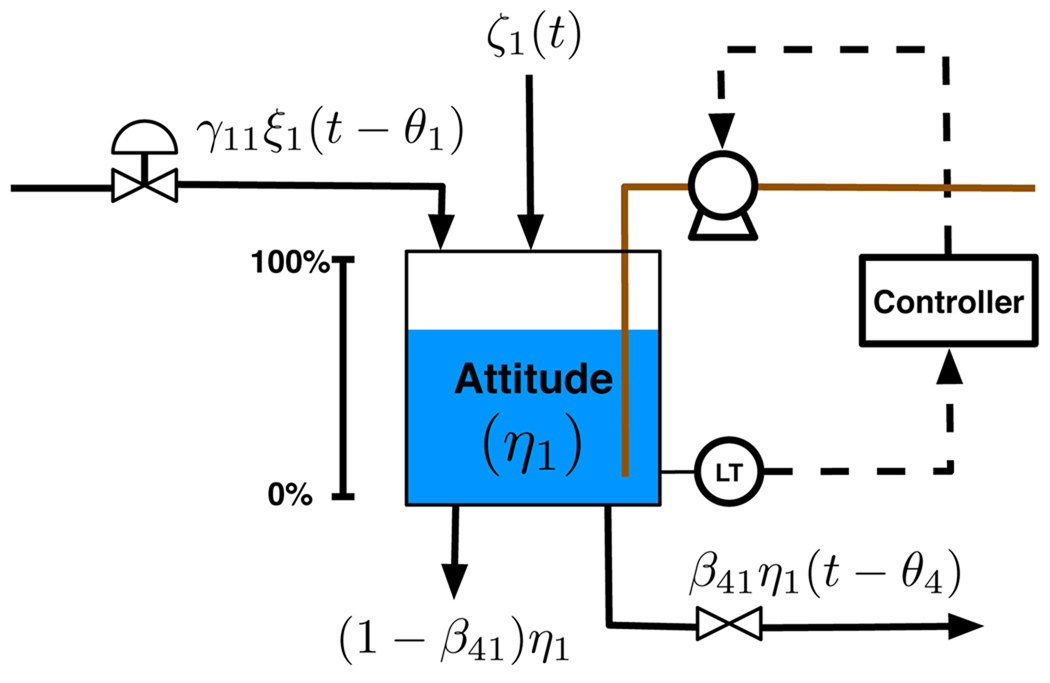

The dynamical model representation according to Equations 29 through 33 can be extended with higher-order derivatives. This enables including additional parameters which can generate a greater diversity of dynamical system responses, such as underdamped and inverse response. Using the case of the attitude inventory as an example, it is possible to rewrite equation 29 as

| (40) |

The parameter ς indicates a damping coefficient that can be used to define overdamped (ς > 1), critically damped (ς = 1), or underdamped (0 ≤ ς < 1) system responses, while τa can be used to introduce model zeros that can lead to non-minimum phase system phenomena such as inverse response (τa < 0). An extension of the fluid analogy to account for the higher-order dynamics brought about by the use of second derivatives is shown in Figure 6. Here the action of a feedback controller acting on measured values of the inventory and controlling a reversible pump would potentially result in a richer variety of dynamic responses that cannot be observed from the first-order model according to (29).

Figure 6.

Fluid analogy for representing attitude in a dynamic TPB model using second-order derivatives.

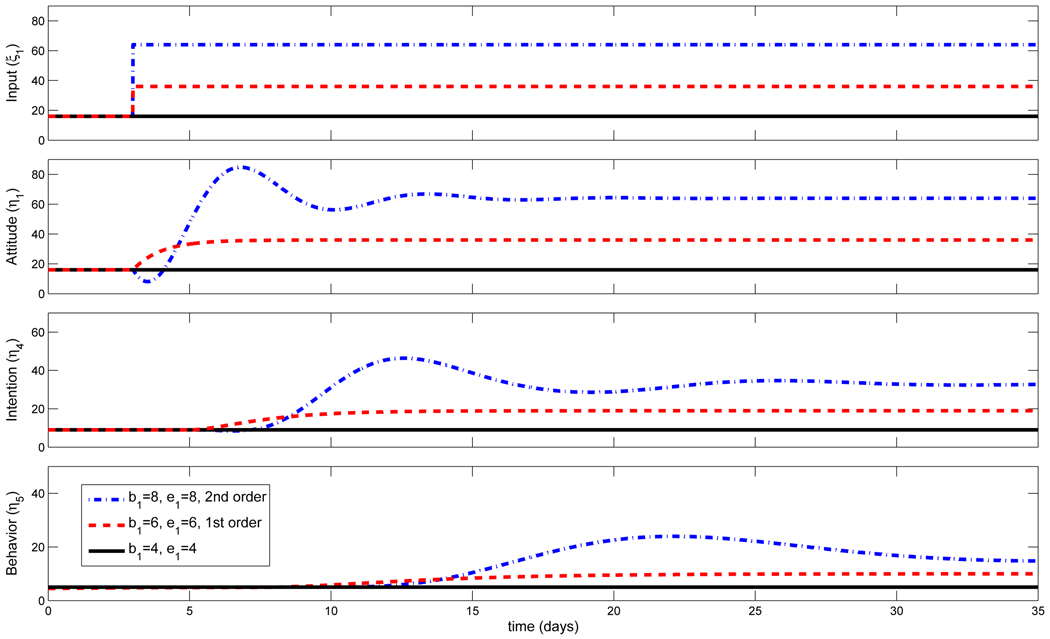

For illustrative purposes, we show in Figure 7 the dynamic response of the fluid analogy for TPB after a step change on the variable ξ1 for the inflow to the attitude inventory in the case of first-order models (dashed red line) and second-order models (dash-dotted blue line). We consider two different interventions changing the values of the strength of beliefs and evaluation of the outcomes from {b1 = 4, e1 = 2}, i.e. ξ1 = 8 to {b1 = 6, e1 = 6}, i.e. ξ1 = 36 for the first-order case and {b1 = 8, e1 = 8}, i.e., ξ1 = 64, for the second-order case, respectively. The other two exogenous variables are left constant at ξ2 = ξ3 = 1. We assume no time delays for the exogenous variables (θ1 = ⋯ = θ3 = 0). A time delay of two days is assumed for the inflows on both intention and behaviour tanks (θ4 = ⋯ = θ8 = 2). The inventories for attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioural control have the same time constant τ1 = τ2 = τ3 = 1 day, whereas the inventories for intention and behaviour have time constants of τ4 = 2 and τ5 = 4 days, respectively. The exogenous inflow resistances are set to unity (γij = 1), whereas the outflow resistance for all inventories is βij = 0.5. This means that only half of the outflow serves as an inflow to the next inventory in the series. No disturbances are considered in this simulation, i.e. ζi = 0. For the second order system, the damping coefficient is ς = 0.3 for all inventories, while τa = −3 for the attitude inventory and τa = 0 for the other inventories. The responses in Figure 7 demonstrate that even with a low-order system a diverse series of dynamical responses can be obtained, among these overdamped (red dashed line, all inventories), underdamped (blue dash-dotted line, all inventories), and inverse response (attitude inventory, blue dash-dotted line). The lag between the inventories is reflected in increasingly longer settling times and consequently slower dynamics between attitude, intention, and behavior.

Figure 7.

Step response for the dynamic fluid analogy of the TPB for different ξ1 = b1 × e1 values, and contrasting first-order (red dashed line) versus second-order (dash-dotted blue line) responses. For the second order system, the damping coefficient is ς = 0.3 for all inventories. τa = −3 for the attitude inventory and τa = 0 for the other inventories. Additional parameters are ξ2 = ξ3 = 1, θ1 = ⋯ = θ3 = 0, θ4 = ⋯ = θ8 = 2, τ1 = τ2 = τ3 = 1, τ4 = 2, τ5 = 4, γij = 1, βij = 0.5 and ζi = 0.

4. Simulation Study

The overall dynamical model for the behavioural intervention integrates the energy balance model described in Section 2.2 and the dynamic fluid analogy for the TPB described in Section 3.2 by having the output of two distinct TPB models (representing physical activity and diet behaviours, respectively) serve as inputs to the mechanistic energy balance model. This enables the impact of the intervention to be observed in both psychological and physical outcome variables over time. Figure 8 expands on the general system diagram shown in Figure 1. The inputs for the behavioural models are the intervention dosage levels applied to the three components of the TPB: attitude toward behaviour (the strength of the beliefs about the outcome b1 and the evaluation of the outcome e1), subjective norm (the normative beliefs n1 and the motivation to comply m1) and the perceived behavioural control (strength of control belief c1 and the perceived power of control p1). The outputs of the behavioural model, namely, the changes on eating habits and exercise, are translated into changes in diet and physical activity, respectively, which are the inputs for the energy balance model. For the three compartment model, diet is subdivided into four different signals: carbohydrate intake CI, fat intake FI, protein intake PI and sodium consumption [Na]. The outputs of the energy balance model are the fat mass FM, the lean tissue mass LM, and the extra-cellular fluid mass ECF.

Figure 8.

The dynamical model for behavioural interventions integrates the energy balance model described in Section 2.2 and the dynamic fluid analogy for the TPB described in Section 3.2.

In this section, we present two simulation scenarios that depict some of the useful ways in which behavioural scientists could utilize the proposed intervention model. The first study (Section 4.1) is a participant-focused scenario where the main goal is to analyse the different behavioural responses that could be obtained for a fixed intervention, given different parameter values among participants. The second study (Section 4.2) is an intervention-focused scenario where the main goal is to use the model to examine the order of intervention components and thus optimise the intervention for a particular individual.

4.1. Understanding participant variability through simulation

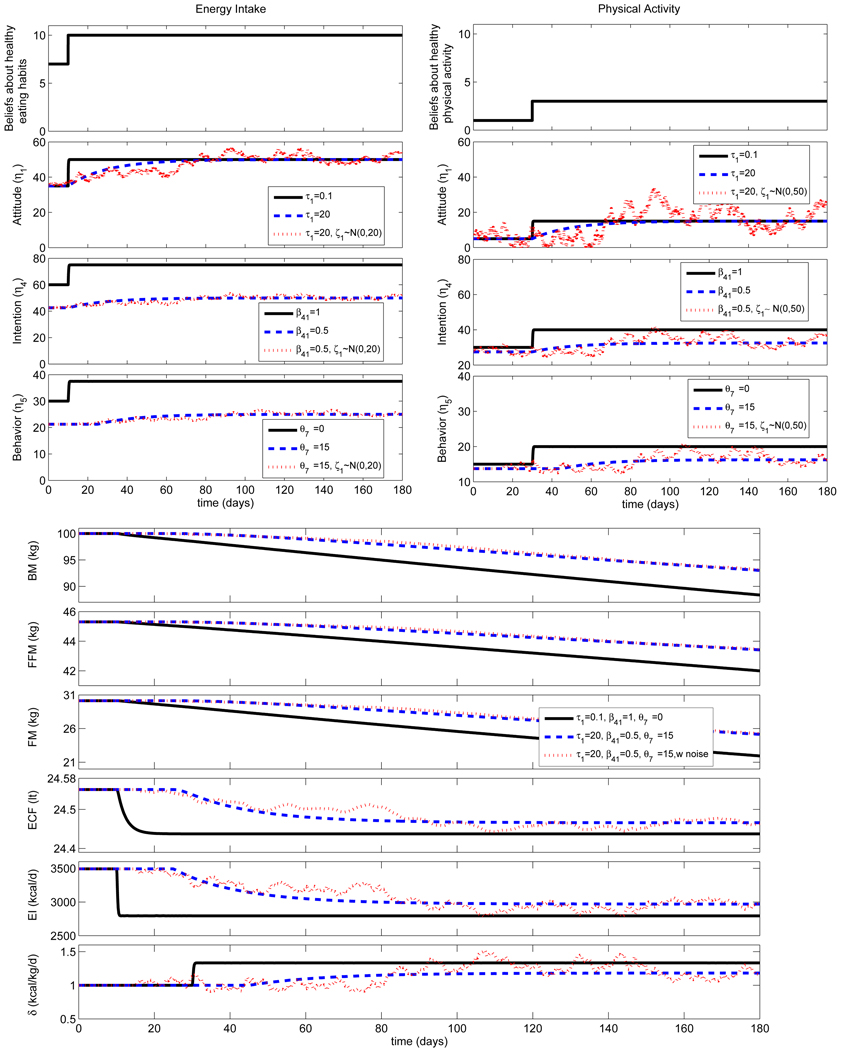

The simulation study in this section consists of examining the effects over time of an intervention promoting healthy eating habits and increased physical activity for a representative male participant with the following initial conditions: BM = 100 kg, FM = 30 kg, FFM = 45 kg and ECF = 25 kg. The initial energy intake is EI = 3500 kcal/d, where the diet consists of carbohydrates CI = 482 g, fat FI = 124 g, and protein PI = 112 g. The initial physical activity coefficient is δ = 1 kcal/kg/d. Figure 9 (top) shows the responses of the intervention on TPB models for energy intake behaviour (EI-TPB) and physical activity behaviour (PA-TPB). Figure 9 (bottom) shows the changes in the body compartments corresponding to these interventions. We consider a scenario in which as a result of the intervention the intensity of beliefs about healthy eating habits increases from b1 = 7 to b1 = 10. This change leads to an increase on the exogenous variable ξ1 in the EI-TPB system. In the same manner, we assume that as a result of the intervention there is a change in the beliefs about proper exercising from b1 = 1 to b1 = 3, which also leads to an increase on the variable ξ1 but in the PA-TPB system. For simplicity, no outflow from the inventory PBC to the inventory behaviour is considered for both behavioural models, i.e. β53 = 0.

Figure 9.

(top) Responses for the energy intake behaviour (EI-TPB) and physical activity behaviour (PA-TPB) models for interventions influencing beliefs about the outcome b1; (bottom) changes in body compartments and total effect of intervention on EI and PA. Simulations for the following intervention cases: (i) complete assimilation τ1 = 0.1, β41 = 1, θ7 = 0, (ii) partial assimilation τ1 = 20, β41 = 0.5, θ7 = 15, and (iii) partial assimilation as in case (ii) but with noise ζ1 ~ N(0, 20) (for EI), and ζ1 ~ N(0, 50) (for PA). Additional parameters: ξ2 = ξ3 = 50, θ1 = ⋯ = θ6 = 0, θ8 = 0, τ2 = ⋯ = τ5 = 0.1, γij = 1, β43 = β54 = 0.5 and β53 = 0.

For this simulation study we consider the following three sub-scenarios:

The participant fully assimilates the intervention and almost immediately starts improving eating habits and engaging in exercise. This means a rapid time constant in the attitude inventory (τ1 = 0.1), no depletion in the intention inventory (β41 = 1) and no delay in the behaviour inventory (θ7 = 0).

The participant partially and slowly assimilates the intervention. This is represented by a large time constant in the attitude (τ1 = 20 days), depletion on intention of β41 = 0.5 (only 50% of the outflow makes the next inventory) and a delay in behaviour of θ7 = 15 days.

The same scenario as for case ii) but with disturbances on the attitude towards healthy eating and exercising. These disturbances are represented as white noise signals ζ1 ~ N(0, 20) and ζ1 ~ N(0, 50) for the energy intake and physical activity TPB models, respectively.

After a step change in ξ1 is introduced, changes are observed in the magnitude level of the inventories for attitude, intention and behaviour, respectively. Figure 9 shows that the attitude response in scenario (ii) takes a larger number of time steps to reach the steady-state when compared to scenario (i). This occurs because of the different τ1 values; the larger value of τi represents slower dynamics and a longer transition of the system to the new steady state. Moreover, the level of intention in scenario (ii) is much lower than in scenario (i). The smaller the value for βij, the larger the depletion. Finally, the change in behaviour in scenario (ii) starts much after the change in behaviour in scenario (i). The larger the value for θi, the longer the delay.

A number of conclusions can be drawn from these simulation results. The most significant is the contrast between the results of case (i) versus case (ii) after a six-month time period. The weight for the participant in case (i) decreases by almost 10 kg over the six months, whereas for case (ii) the weight loss is only 7 kg. The behavioural “lag” has resulted in a substantially lower achievable weight loss for the participant. However, despite the presence of stochastic disturbances in case (iii) and correspondingly large fluctuations on the amplitude for some of the inventory levels in the TPB models, these do not result in significant differences on total body weight loss when compared to case (ii).

4.2. Intervention optimisation through simulation

The simulation study in this section consists of using the dynamical model summarized in Figure 8 to examine the effects of changing facets of the intervention for an individual or group displaying fixed characteristics. The term “optimisation” is used loosely as formal optimisation methods will not be applied; rather we present a case in which the model informs the user on the proper order of intervention components for a given participant (or participant group). We examine the effects over time of two different interventions promoting healthy eating habits and increased physical activity for a representative female participant, 1.70 m tall, at the following initial conditions: BM = 80 kg, FM = 28 kg, LM = 32 kg and ECF = 20 kg. The initial energy intake is EI = 3500 kcal/d, where the initial diet consists of CI = 482 g, FI = 124 g, and PI = 112 g. The initial physical activity coefficient is δ = 1 kcal/kg/d. Table 2 shows the time constants τi and time delays θi and Table 3 shows the gains assumed for the participant, respectively. The gains βij for behavioural eating habits and exercising have been taken from the literature [32, 35].

Table 2.

Time constants τi and time delays θi assumed for female participant in simulation study for different intervention order shown in Figure 10.

| Parameter | EI-TPB | PA-TPB |

|---|---|---|

| τ1 | 20 | 30 |

| τ2 | 30 | 30 |

| τ3 | 10 | 10 |

| τ4 | 10 | 20 |

| τ5 | 30 | 30 |

| θ1, ⋯, θ3 | 0 | 0 |

| θ4, ⋯, θ6 | 5 | 10 |

| θ7 | 20 | 20 |

| θ8 | 15 | 20 |

Table 3.

Inflow and outflow gains γij, βij assumed for female participant in simulation study for different intervention order shown in Figure 10.

| Parameter | EI-TPB | PA-TPB |

|---|---|---|

| γ11 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| γ22 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| γ33 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| β41 | 0.16 | 0.34 |

| β42 | 0.04 | 0.27 |

| β43 | 0.59 | 0.13 |

| β53 | 0.1 | 0.08 |

| β54 | 0.32 | 0.42 |

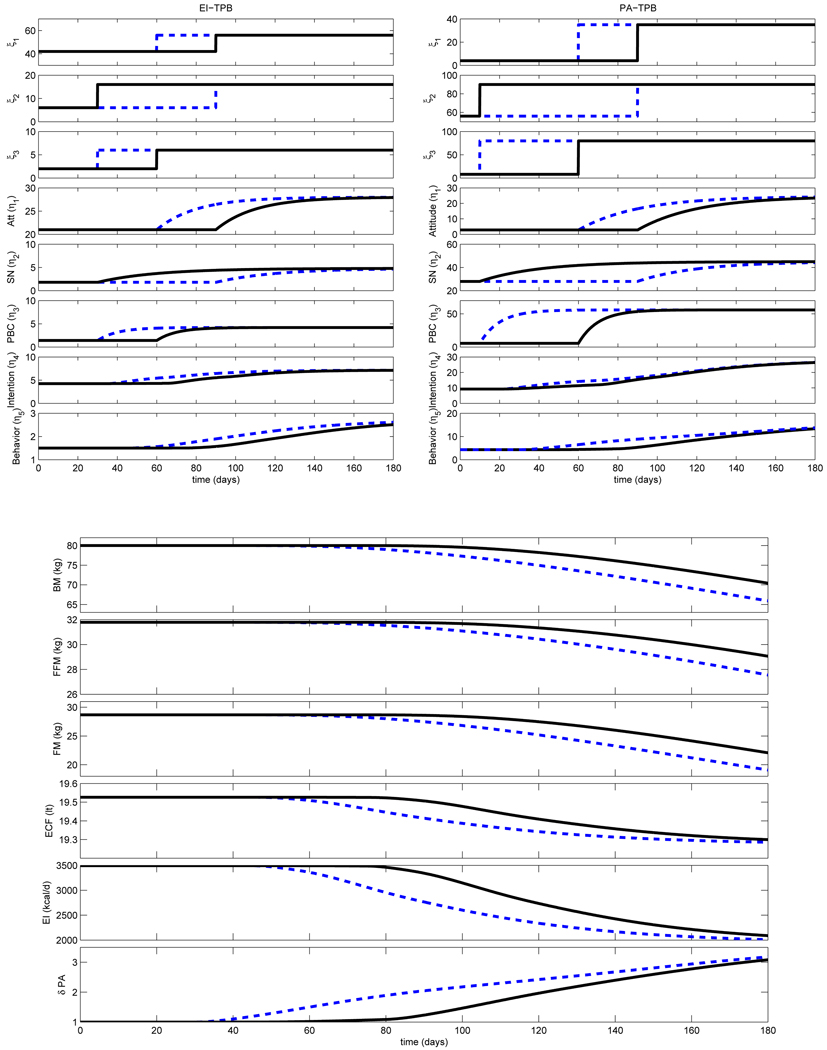

The assumption in the two interventions cases is that each accomplishes equivalent changes to the inputs of the energy intake (EI-TPB) and physical activity (PA-TPB) TPB models; these changes are listed in Table 4. The order in which these changes are introduced differ, as summarized below:

Intervention Sequence A. For energy intake, the intervention components addressing subjective norms begin at day t = 30, while those influencing perceived behavioural control and attitude occur at day t = 60 and day t = 90, respectively. For physical activity, intervention components influencing subjective norms enter at day t = 10, while those addressing perceived behavioural control and attitude occur at at day t = 60 and day t = 90, respectively. This intervention sequence is represented with solid curves in Figure 10.

Intervention Sequence B. For energy intake, the intervention components addressing perceived behavioural control begin at day t = 30, while those influencing attitude and subjective norms occur at day t = 60 and day t = 90, respectively. For physical activity, intervention components influencing perceived behavioural control enter at day t = 10, while those addressing attitude and subjective norms occur at at day t = 60 and day t = 90, respectively.

Table 4.

Behavioural changes on diet and exercising for simulation study for different intervention order shown in Figure 10.

| Parameter | EI-TPB | PA-TPB |

|---|---|---|

| b1 | 7 → 8 | 1 → 5 |

| e1 | 6 → 7 | 4 → 7 |

| s1 | 2 → 4 | 7 → 9 |

| m1 | 3 → 4 | 8 → 10 |

| p1 | 1 → 2 | 4 → 10 |

| c1 | 2 → 3 | 2 → 8 |

Figure 10.

(top) Responses for the energy intake behaviour (EI-TPB) and physical activity behaviour (PA-TPB) models for two intervention sequences; (bottom) changes in body compartments and total effect of the intervention on EI and PA. Simulations for the following intervention cases: intervention sequence A (solid), leading to a decrease on weight of 10 kg in 6 months, and intervention sequence B (dashed), leading to a weight loss of 15 kg during the same time period. Additional parameters are shown in Tables 2, 3 and 4

Figure 10 (top) shows the participant response for the EI-TPB and PA-TPB models, while Figure 10 (bottom) shows the changes in body composition corresponding to these interventions. Sequence A results in 10 kg total weight loss after six months, while Sequence B accomplishes 15 kg total weight loss in the participant during the same time period.

The simulation results indicate that intervention sequence B represents a more suitable alternative for the participant under study than sequence A. Figure 10 (top) shows that improved outcomes are obtained in intervention sequence B by placing a priority in the intervention on perceived behavioural control in lieu of subjective norms. This action leads to faster changes in behaviour for both energy intake and physical activity, in contrast to intervention sequence A. This occurs because for the particular gain values γij and βij which define this participant, it is more prudent to apply first an intervention that affects perceived behavioural control and attitude, rather than subjective norms. Moreover, the levels of these inventories reach a steady state much faster than for the subjective norm inventory. Finally, because the inventory for perceived behavioural control has two outflows (one flowing into the intention inventory, and the other flowing into behaviour), a larger constant inflow into the inventory of perceived behavioural control leads to a larger inflow in the inventories for intention and behaviour when using Sequence B, in lieu of Sequence A.

5. Summary and Conclusions

A dynamical model for a behavioural intervention associated with weight loss and body change composition has been proposed that provides a potentially useful framework for understanding and optimising this class of interventions. By testing the effect of intervention components on outcomes of interest over time, the intervention scientist can optimally decide on aspects of the intervention such as the ordering and strength of the components, and can better predict both the inter- and intra-individual variability that will be reflected in these interventions.

Extensions of this simulation work include incorporating additional forms of random disturbances and model stochasticity in order to more closely mimic actual responses. An extended version of the dynamic TPB model where the endogenous variables are latent as opposed to observed variables has also been examined; it has not been presented in this paper for reasons of brevity.

The simulation results point to the need for data from experimental trials or observational studies that can be used to estimate parameter coefficients in these models and validate the modelling framework. We are currently exploring how methods from the field of system identification [39] and functional data analysis [40], coupled with data resulting from participant diaries or ecological momentary assessment, can be used for this purpose. A long-term goal is to develop adaptive behavioural interventions for preventing weight gain or loss in patients with obesity or malnutrition, relying on control systems engineering principles [6].

Acknowledgements

We thank Kevin D. Hall and Carson C. Chow of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) for providing us with the energy balance equations used in this study. We are also grateful to Danielle Symons Downs of the Department of Kinesiology at Penn State University for insights into the TPB and behavioral interventions for promoting physical activity and healthy eating habits. Support for this research has been provided by the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR), National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) through grants R21 DA024266, K25 DA021173 and P50 DA010075. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Keim NL, Blanton CA, Kretsch MJ. America’s obesity epidemic: Measuring physical activity to promote an active lifestyle. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004;vol. 104(no. 9):1398–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mokdad AH, Bowman BA, Ford ES, Vinicor F, Marks JS, Koplan JP. The Continuing Epidemics of Obesity and Diabetes in the United States. JAMA. 2001;vol. 286(no. 10):1195–1200. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.10.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.W. H. Organization. Diet and physical activity: a public health priority. [Accesed December 23, 2009];WHO; tech. rep. 2008

- 4.Baranowski T, Cullen K, Nicklas T, Thompson D, Baranowski J. Are current health behavioral change models helpful in guiding prevention of weight gain efforts? Obesity Research. 2003;vol. 11:23S–43S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall K, Jordan P. Modeling weight-loss maintenance to help prevent body weight regain. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;vol. 88:1495–1503. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rivera DE, Pew MD, Collins LM. Using engineering control principles to inform the design of adaptive interventions: A conceptual introduction. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;vol. S31:S31–S40. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ajzen I, Madden T. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1986;vol. 22:453–474. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garrow J. Energy Balance and Obesity in Man. Amsterdam: Elsevier/North-Holland Biomedical Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garrow J. Energy balance in man - an overview. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1987;vol. 45:1114–1119. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/45.5.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westertep K, Donkers J, Fredrix E, Boekhoudt P. Energy intake, physical activity and body weight: a simulation model. British Journal of Nutrition. 1995;vol. 73:337–347. doi: 10.1079/bjn19950037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McArdle W, Katch F, Katch V. Exercise Physiology: Energy, Nutrition, and Human Performance. Baltimore MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdel-Hamid T. Modeling the dynamics of human energy regulation and its implications for obesity treatment. System Dynamics Review. 2002;vol. 18(no. 4):431–471. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall KD. Computational model of in vivo human energy metabolism during semistarvation and refeeding. American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2006;vol. 291:E23–E37. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00523.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chow CC, Hall KD. The dynamics of human body weight change. PLoS Computational Biology. 2008;vol. 4(no. 3):1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas DM, Ciesla A, Levine JA, Stevens JG, C.K. M. A mathematical model of weight change with adaptation. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2009;vol. 6:837–887. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2009.6.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas DM, Martin CK, Heymsfield S, Redman LM, Schoeller D, Levine J. A simple model predicting individual weight change in humans. Journal of Biological Dynamics. 2010 doi: 10.1080/17513758.2010.508541. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall K. Mechanisms of metabolic fuel selection: Modeling human metabolism and dody-weight change. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 2010 Jan–Feb;vol. 29:36–41. doi: 10.1109/MEMB.2009.935465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall K. Predicting metabolic adaptation, body weight change, and energy intake in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;vol. 298(no. 3):E449–E466. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00559.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keys A, Brozek J, Henschel A, Mickelsen O, Taylor HL. The Biology of Human Starvation. vol. 1,2. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 20.F. E. Consultation. Human energy requirements. Rome: FAO; Food and Nutrition Technical Report Series 1. 2001 October;

- 21.Trumbo P, Schlicker S, Yates A, M P. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein and amino acids. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2002;vol. 102(no. 11):1621–1630. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merrill A, Watt B. Energy value of foods - Basis and derivation, vol. 74 of Agriculture Handbook. U.S. Department of Agriculture; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whitney EN, Rolfes SR. Understanding Nutrition. Bemont, CA: West/Wadsworth; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dugdale A, Payne P. Pattern of lean and fat deposition in adults. Nature. 1977;vol. 266:349–351. doi: 10.1038/266349a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall KD. Body fat and fat-free mass inter-relationships: Forbes’ theory revisited. British Journal of Nutrition. 2007;vol. 97(no. 6):1059–1063. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507691946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forbes GB. Lean body mass-body fat interrelationships in humans. Nutr Rev. 1987;vol. 45:225–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1987.tb02684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson AS, Stanforth PR, Gagnon J, Rankinen T, Leon A, et al. The effect of sex, age and race on estimating percentage body fat from body mass index: The heritage family study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;vol. 26:789–796. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silva AM, Wang J, Pierson J, N R, Wang Z, Spivack Jea. Extracellular water across the adult lifespan: reference values for adults. Physiol Meas. 2007;vol. 28:489–502. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/28/5/004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Antonetti VW. The equations governing weight change in human beings. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1973;vol. 26:64–71. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/26.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Navarro-Barrientos JE, Rivera DE. A dynamical systems model for weight change behavioral interventions. Control Systems Engineering Laboratory, Arizona State University; tech. rep. 2010 CSEL Technical Progress Report 2010-01, http://csel.asu.edu/downloads/Publications/techreport/CSELtechreport2010-01.pdf.

- 31.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blanchard CM, Fisher J, Sparling PB, Shanks TH, Nehl E, Rhodes RE, Courneya KS, Baker F. Understanding adherence to 5 serving of fruits and vegetables per day: A theory of planned behavior perspective. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2009;vol. 41(no. 1):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Godin G, Valois P, Lepage L. The pattern of influence of perceived behavioral control upon exercising behavior: An application of ajzen’s theory of planned behavior. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1993;vol. 16(no. 1):81–102. doi: 10.1007/BF00844756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norman P, Conner M, Bell R. The theory of planned behaviour and exercise: Evidence for the moderating role of past behaviour. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2000;vol. 5:249–261. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Downs D. Symons, Hausenblas HA. The theories of reasoned action and planned behavior applied to exercise: A meta-analytic update. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2005;vol. 2:76–97. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. Series in probability and mathematical statistics, Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raykov T, Marcoulides GA. A First Course in Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartz JD, Wang W, Rivera DE. Optimal tuning of process control-based decision policies for inventory management in supply chains. Automatica. 2006;vol. 42:1311–1320. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ljung L. System Identification: Theory for the User. Prentice Hall: Prentice Hall Information and System Sciences Series; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramsay J, Silverman B. Functional Data Analysis. Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]