Summary

Labile memory is thought to be held in the brain as persistent neural network activity [1–4]. However, it is not known how biologically relevant memory circuits are organized and operate. Labile and persistent appetitive memory in Drosophila requires output after training from the α′β′ subset of mushroom body (MB) neurons and from a pair of modulatory Dorsal Paired Medial (DPM) neurons [5–9]. DPM neurons innervate the entire MB lobe region and appear to be pre- and post-synaptic to the MB [7, 8], consistent with a recurrent network model. Here we identify a role after training for synaptic output from the GABAergic Anterior Paired Lateral (APL) neurons [10, 11]. Blocking synaptic output from APL neurons after training disrupts labile memory but does not affect long-term memory. APL neurons contact DPM neurons most densely in the α′β′ lobes although their processes are intertwined and contact throughout all the lobes. Furthermore, APL contacts MB neurons in the α′ lobe but makes little direct contact with those in the distal α lobe. We propose that APL neurons provide widespread inhibition to stabilize and maintain synaptic specificity of a labile memory trace in a recurrent DPM and MB α′β′ neuron circuit.

Results and Discussion

Fruit flies form robust aversive or appetitive olfactory memory following a training session pairing odorant exposure with electric shock punishment or sucrose reward, respectively [12, 13]. Olfactory memories are believed to be stored in the output synapses of third order olfactory system neurons in the MB [5, 14–16], a symmetrical structure comprised of roughly 2500 neurons on each side of the brain that can be structurally and functionally dissected into αβ, α′β′, and γ neuron systems [5, 17].

Similar to aversive memory, appetitive memory measured three hours after training is referred to as middle-term memory and is comprised of a labile anesthesia sensitive memory (ASM) and an anesthesia resistant memory (ARM) component [18–20]. Both of these phases and later long-term memory (LTM) require the action of the DPM neurons [5–9, 21, 22]. DPM neurons exclusively innervate the lobes and base of the peduncle regions of the MB [9, 21] where functional imaging suggests they are pre- and post-synaptic to MB neurons [7]. DPM neuron projections to the α′β′ MB neuron subdivision appear to be of particular importance and blocking output from α′β′ neurons themselves during a similar time period after training phenocopies a DPM neuron block [5, 8, 9]. These data lead us to propose that reverberant activity in a recurrent MB α′β′ to DPM neuron circuit is required to hold labile memory and for consolidation to LTM within αβ neurons [5, 9, 23]; where output is critical for retrieval of LTM [9, 23].

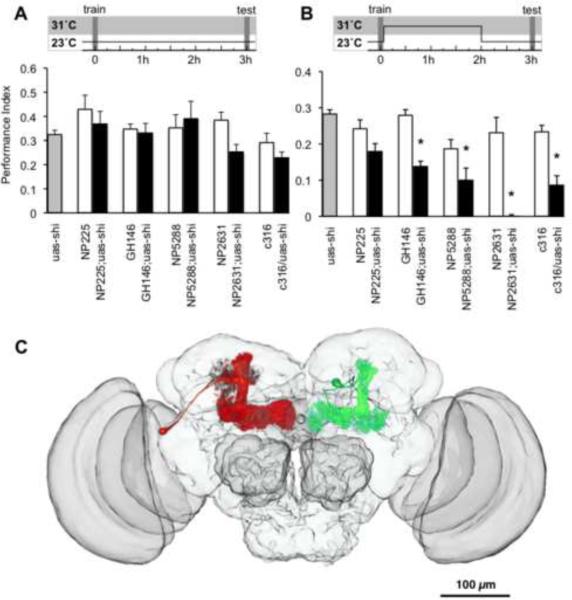

As part of a screen for additional neurons contributing to appetitive memory processing after training, we tested for a role of the second order olfactory projection neurons (PN). We expressed a uas-shibirets1 transgene [25] with the two most frequently utilized PN GAL4 drivers, GH146 and NP225 [26]. The uas-shits1 transgene allows one to temporarily block synaptic transmission from specific neurons by shifting the flies from the permissive temperature of <25°C to the restrictive temperature of >29°C. We tested appetitive olfactory memory in GH146;uas-shits1 and NP225;uas-shits1 flies in parallel with control flies harboring the GAL4 drivers or uas-shits1transgene alone. We also tested c316/uas-shits1 flies, in which the DPM neurons were blocked for comparison. No defects were apparent when the flies were trained and tested at the permissive temperature (Figure 1A). To test for a role after training, all flies were trained at 23°C and immediately after training they were shifted to 31°C for 2 hours to disrupt neurotransmission from PN or DPM neurons. All flies were then returned to 23°C and tested for 3hr memory. Memory was significantly impaired by GH146;uas-shits1 and c316/uas-shits1 manipulation but not by NP225;uas-shits1. The performance of GH146;uas-shits1 and c316/uas-shits1 flies was significantly different from their respective control flies. In contrast, the performance of NP225;uas-shits1 flies was not significantly different from control flies (Figure 1B). GH146 and NP225 label a large number of largely overlapping projection neurons [26]. However, since NP225; uas-shits1 flies did not exhibit a memory defect (n=24) we concluded that other neurons labeled by GH146 that are downstream of PN could be responsible for the observed memory defect. GH146 most obviously differs from NP225 by also expressing in two Anterior Paired Lateral (APL) neurons that innervate the MB [10, 11, 26]. Each APL ramifies throughout the entire ipsilateral MB [10, 11]. This anatomy is similar to the DPM neurons which project ipsilaterally throughout the MB lobes and base of the peduncle [10, 21] (Figure 1C). We therefore further investigated whether the APL neurons were required for memory processing after training.

Figure 1. Blocking APL or DPM neurons after training disrupts memory.

The temperature shift protocols are shown pictographically above each graph. (A) The permissive temperature of 23°C does not affect 3hr appetitive odor memory of any of the lines used in this study. All genotypes were trained and tested for 3hr memory at 23°C. (B) Blocking APL or DPM neurons after training impaired 3hr appetitive odor memory. Flies were trained at 23°C and immediately after training were shifted to 31°C for 2hr. Flies were then returned to 23°C and tested for 3hr odor memory. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between the marked groups and the relevant controls (all P<0.05). Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). (C) 3D reconstruction of a fly brain showing a single APL (red) and DPM (green) neuron to illustrate the location of their soma and their ipsilateral projections in the MB.

The NP5288 and NP2631 GAL4 lines have also been reported to label the APL neurons [10]. NP5288 is expressed in a similar subset of PNs to that of NP225 [27], as well as a few other distributed neurons in the brain. NP2631 does not label PNs but labels many other neurons in the brain including labeling in the median bundle, protocerebral bridge and subesophageal ganglion. We tested the consequence on memory of blocking synaptic output after training from the neurons labeled in these additional APL-expressing lines. As before, no apparent defects were observed when the flies were trained and tested at the permissive temperature (Figure 1A). However, flies trained at 23°C, shifted to 31°C for 2hr after training and tested for 3hr memory at 23°C revealed defective memory. Memory performance of NP5288;uas-shits1 and NP2631;uas-shits1 flies was statistically different from the performance of their genetic control groups (Figure 1B). These data are consistent with a role for APL neurons in memory processing after training.

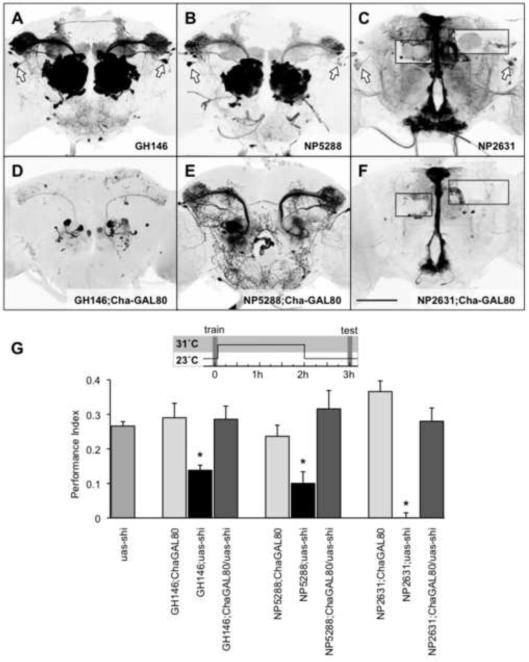

Others have reported that combining a ChaGAL80 transgene with GH146 inhibited expression in the APL neurons but left expression in PNs relatively intact [11]. We utilized this approach to further test the requirement of uas-shits1 expression in APL neurons for our observed memory defects. We combined the ChaGAL80 transgene with the GH146, NP5288 and NP2631 GAL4 drivers and an uas-mCD8∷GFP to visualize the extent of GAL4 inhibition by ChaGAL80 in these flies. As described for GH146;ChaGAL80 flies [11], confocal imaging of the GFP labeled brains revealed that the ChaGAL80 transgene efficiently suppressed APL expression. The APL neurons were evident in all flies lacking ChaGAL80 but were not labeled in any of the three genotypes containing ChaGAL80 (Figure 2A–F). ChaGAL80 affected the expression in other neurons labeled by each GAL4 line to varying degrees. Our analysis revealed a strong inhibition in GFP expression in the PNs labeled by GH146 (Figure 2D) and NP5288 (Figure 2E) although more PNs retained expression in NP5288 than in GH146, consistent with these two GAL4 drivers labeling partially non-overlapping PN populations. ChaGAL80 inhibited APL expression in NP2631 and also removed expression from several other neurons (Figure 2F). Expression was lost in some neurons innervating the subesophageal ganglion whereas robust expression remained in the median bundle and protocerebral bridge of the central complex. Unfortunately several intersectional approaches to create more specific control of APL neurons were unsuccessful (supplemental material).

Figure 2. Expression in APL neurons is required for the memory defect.

Projection view of a brain from an (A) GH146;uas-mCD8∷GFP, (B) NP5288;uasmCD8∷GFP (C) NP2631; uas-mCD8∷GFP, (D) GH146;ChaGAL80/uas-mCD8∷GFP, (E) NP5288;ChaGAL80/uas-mCD8∷GFP and (F) NP2631; ChaGAL80/uas-mCD8∷GFP fly. Inserts in (C) and (F) represent single optical sections at the depth of the horizontal lobes or the calyx of the mushroom body. While NP2631 flies (C) show clear APL innervation in the MB calyx and horizontal lobes, this expression is missing in NP2631;ChaGAL80 flies (F). Scale bar represents 50μm. (G) Removing expression from APL neurons with ChaGAL80 reverses the observed memory defects. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between marked groups and the relevant controls (all P<0.05, ANOVA). Data are mean ± SEM.

We next combined ChaGAL80 with each APL-expressing GAL4 driver and the uas-shits1 transgene to test whether APL expression was necessary for the observed memory phenotypes when GH146, NP5288 and NP2631 neurons were blocked after training (Figure 2G). We assayed memory performance of GH146, NP5288 and NP2631 flies expressing uas-shits1 with or without the ChaGAL80 transgene along with GAL4;ChaGAL80 and uas-shits1 control flies for comparison. We again trained flies at 23°C, shifted them to 31°C for 2hr after training and tested 3hr appetitive memory at 23°C. This manipulation significantly impaired memory performance in all flies without the ChaGAL80 transgene but not in flies with the ChaGAL80 transgene. Memory performance of GH146;uas-shits1, NP5288;uas-shits1 and NP2631;uas-shits1 flies was significantly different from uas-shits1 and GAL4;ChaGAL80 flies. In contrast, memory performance of all flies also harboring the ChaGAL80 transgene was not significantly different from the performance of the genetic control flies (Figure 2G). These data suggest that expression in APL neurons is critical to disrupt 3hr memory when blocking neurotransmission after training.

The memory experiments described did not disrupt synaptic transmission during training or testing. Nevertheless to control for possible confounding effects, we tested the olfactory acuity and motivation to seek sucrose in naïve flies following a 2hr disruption of synaptic transmission and 1hr recovery as employed in the memory experiments (Table S1). No olfactory acuity defects were observed in GH146;uas-shits1 or NP5288;uas-shits1 flies. However, NP2631;uas-shits1 flies exhibited a pronounced defect which questions the validity of the memory experiments with this line (Table S1). We therefore rely on the GH146;uas-shits1 and NP5288;uas-shits1 flies and the comparison to NP225;uas-shits1 flies to draw our conclusions. GH146;uas-shits1 and NP5288;uas-shits1 flies also exhibited sucrose acuity that was statistically indistinguishable from uas-shits1 controls. NP5288;uas-shits1 flies performed better than NP5288 which had an apparent defect (Table S1). These data suggest that 3hr appetitive memory requires synaptic output from the APL neurons after training, similar to the requirement for output from DPM [8, 9] and MB α′β′ neurons [5].

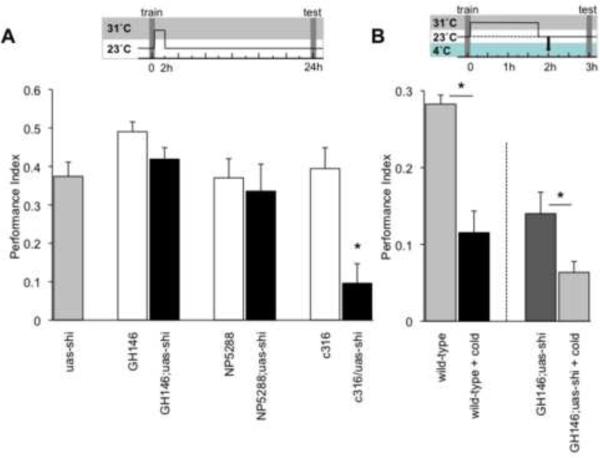

DPM neuron output is also required after training for appetitive LTM [9]. We therefore used GH146 and NP5288 to test whether APL block disrupted LTM. We blocked APL output for 2hr after training and tested 24hr memory. Surprisingly, performance of GH146;uas-shits1 and NP5288;uas-shits1 flies was not significantly different from uas-shits1 or GAL4 flies (Figure 3A) suggesting that APL output is specifically required for an earlier memory phase. Appetitive memory at 3hr has been shown to be sensitive to cold-shock anesthesia delivered 2hr after training [20]. We therefore tested whether APL block affected this labile component by performing experiments with cold-shock (Figure 3B). We trained wild-type flies and 2hr afterwards subjected half of them to a 2min cold-shock, allowed them to recover at room temperature and tested 3hr memory. Performance of these flies was significantly different from those not receiving a cold-shock consistent with previous literature [20]. Interestingly, the performance of GH146;uas-shits1 flies in which APL neurons were blocked for 2hr after training was statistically indistinguishable from cold-shocked wild-type flies. To further test whether APL blocked flies were missing the cold-shock sensitive memory component we combined the shits1 block and cold-shock treatments. We trained GH146;uas-shits1 flies, blocked APL after training by shifting flies to 31°C for 105 minutes, returned them to 25°C for 15 minutes, gave them a 2min cold-shock and tested 3hr memory (Figure 3B). The performance of these flies was statistically different to GH146;uas-shits1 flies that received all treatment except the cold-shock suggesting that some anesthesia sensitive memory was present in GH146;uas-shits1 blocked flies. Importantly, memory performance was not totally abolished. Since significant memory remained following the uas-shits1 block and the cold shock, we conclude that APL neuron block largely affects the labile anesthesia sensitive appetitive memory. However, it is worth noting that APL block and cold-shock cannot be considered to be operationally equivalent because the 2min cold shock at 2hr reduced memory observed at 24hr (Figure S1) whereas blocking APL for 2hr did not impact 24hr memory (Figure 3A). Therefore, blocking GH146 and NP5288 neurons appears to be more specific to labile appetitive memory than cold-shock treatment at this time.

Figure 3. Blocking APL neurons after training does not impair LTM.

The temperature shift protocol is shown pictographically above each graph. (A) Flies were trained at 23°C and immediately after training were shifted to 31°C for 2hr. Flies were then returned to 23°C and tested for 24hr odor memory. Asterisk indicates a significant difference between marked groups and the relevant controls (P<0.05, ANOVA). (B) Cold-shock treatment at 2hr impairs 3hr appetitive memory. Wild-type flies were trained and tested at the permissive temperature or received cold-shock at 2hrs, and were tested for 3hr odor memory. GH146; uas-shits1 flies were trained at 23°C and immediately after training were shifted to 31°C for 105 minutes. Flies were then returned to 23°C and 15min later received a 2min cold-shock and were tested for 3hr odor memory. Asterisk indicates a significant difference between marked groups (P<0.05, ANOVA). GH146;uas-shits1 + cold shock flies were significantly different from zero (P<0.001, Mann-Whitney U). Data are mean ± SEM.

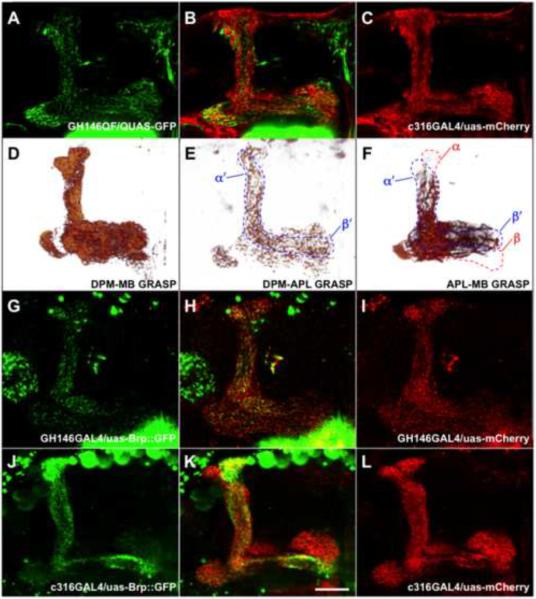

The APL neurons are known to be GABAergic [11] and finding that they are critical for labile memory is consistent with inhibitory input stabilizing the putative MBDPM recurrent network [28]. We therefore examined the anatomy of APL neurons in relation to DPM and MB neurons. Prior work has shown that APL neurons ramify throughout the calyx, peduncle, and all lobes of the MB [10, 11] whereas DPM neuron projections are confined to the lower peduncle and MB lobes [10, 21]. We simultaneously imaged DPM and APL neuron projections onto the MB by expressing uas-mCD8∷mCherry in DPM neurons with the c316-GAL4 driver and QUAS-mCD8∷GFP in APL neurons with an APL-expressing GH146-QF driver [29] (Figure 4A–C). This analysis revealed that APL neurons have a more reticular structure throughout the lobes (Figure 4A) while DPM processes are punctate and are most dense in the α′β′ lobes (Figure 4C). APL processes are interspersed with those of DPM in regions of overlapping innervation (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. APL and DPM processes in the MB are morphologically different.

(A–C) Single confocal sections through a brain from a GH146QF/QUAS-mCD8∷GFP;c316/uas-mCherry fly brain at the level of the horizontal lobes of the MB. (A) APL driven mCD8∷GFP (green) reveals an even reticular network across all MB subdomains and more dense label in the heel region. (B) APL processes intermingle with mCherry marked DPM processes (red). (C) DPM processes are most dense in the α′β′ lobes, and fairly sparse in the αβ core. (D) Voltex projection of the lobe region of DPM-MB GRASP (MBGAL80/lexAop-mCD4∷spGFP11;c316,247-LexA/uas-mCD4∷spGFP1-10). The GRASP signal reveals dense contact between DPM and MB neurons throughout the DPM innervation pattern. (E) A voltex projection of DPM-APL GRASP (NP5288,L0111-LexA/lexAop-mCD4∷spGFP11;uas-mCD4∷spGFP1-10). Sparse contacts are present in all the lobes and particularly evident in the α′β′ lobes (outlined) and the base of the peduncle. (F) Voltex projection of the lobe region of APL-MB GRASP (NP5288/lexAop-mCD4∷spGFP11;247-LexA/uas-mCD4∷spGFP1-10). Contacts between APL and MB neurons are most obvious in the heel and the region of each lobe most proximal to the junction. Unlike the evenly distributed net-like APL innervation pattern, APL-MB contacts diminish towards the tips of the lobes, most obviously in the distal α lobe where no APLMB proximity is apparent. (G–I) Single confocal sections at the level of the MB lobes from a GH146/uas-Brp∷GFP,uas-mCD8∷mCherry fly brain. (G,H) Brp∷GFP labels putative synaptic active zones of APL throughout the MB lobes with more dense labeling in the α′β′ lobes. (I) Co-expressed mCherry reveals normal APL morphology. (J–L) Single confocal sections at the level of MB lobes from a uas-Brp∷GFP,c316/uas-mCD8∷mCherry fly brain. (J,K) Brp∷GFP labels putative synaptic active zones of DPM throughout the MB lobes with most dense labeling in the αβ lobes. (L) Co-expressed mCherry shows normal DPM morphology. Scale bar represents 25μm.

To determine possible sites of cell-cell contact we used GFP Reconstitution Across Synaptic Partners (GRASP) [30, 31]. GRASP is detectable when neurons expressing complementary parts of an extracellular split-GFP are close enough so that functional GFP is reconstituted [30]. We constructed flies that express lexAop-CD4∷spGFP11 [31] in MB with 247-LexA and uas-CD4∷spGFP1-10 [31] in APL or DPM with NP5288 or c316-GAL4. This analysis revealed distinct innervation of the MB by DPM and APL. DPM-MB GRASP was very dense and punctate throughout the MB lobes and peduncle and generally resembled the mCD8∷GFP pattern covering all the major MB lobe regions (Figure 4D and Movie S1). APL-MB GRASP is most notable for structure that is absent (Figure 4F and Movie S2). The regular net-like appearance of APL seen with CD8∷GFP (Figure 4A) is not apparent and label mostly decorates fibers running in parallel with MB neurons in the lobes. APL-MB GRASP in the vertical lobes is particularly revealing. Whereas the APL CD8∷GFP network extends throughout the vertical lobes (Figure 4A and for mCD8∷mCherry in 4I), APL-MB GRASP labels processes extending in the α′ lobe but very little in the α lobe (Figure 4F). Since GRASP is most reliably an indicator of proximity rather than connectivity, these data indicate that much of the APL network is distant to the MB neurons in the α lobe. We also used GRASP to visualize contact between APL and DPM neurons using NP5288-GAL4 for APL and L0111-LexA for DPM (Figure 4E, S2 and Movie S3). APL-DPM GRASP revealed punctate labeling throughout the MB lobes that was most dense in the α′β′ lobes and base of the peduncle region (Figure 4E). We conclude that APL contacts DPM and MB neurons preferentially in the α′ lobe. In the horizontal lobes APL contacts DPM throughout and makes dense contact with proximal portions of the MB β, β′ and γ neurons. The density of contact decreases towards the distal end of each horizontal lobe. It seems plausible that APL contacts other unidentified neurons especially in the areas where they are apparently avoiding MB neurons.

We also labeled pre-synaptic active zones in APL and DPM neurons by expressing a uas-Bruchpilot∷GFP [32] with a mCD8∷mCherry [33] transgene that should label the entire cell surface. Brp∷GFP driven in APL with GH146 revealed presynaptic zones throughout the MB lobes with elevated levels in the α′β′ lobes (Figure 4G–I). In contrast, Brp∷GFP driven in DPM neurons with c316 revealed presynaptic zones throughout the lobes but very pronounced labeling in the αβ lobes (Figure 4J–L).

The anatomical data are consistent with a model of a recurrent MB α′β′-DPM-APL circuit and flow of activity from the α′β′ lobes through the DPM neurons to the αβ lobes (Figure S3). Importantly, GRASP suggests APL and DPM contact is most dense within the α′β′ lobes and Brp∷GFP indicates strongest APL neurotransmitter release in α′β′. APL-MB GRASP indicates that APL preferentially contacts α′β′ MB neurons (most apparent in the vertical lobes). Interestingly, others found that APL and DPM neurons are electrically coupled via heterotypic gap junctions (A-S. Chiang and G. Turner, personal communication). It will therefore be important to determine if APL-DPM contact in α′β′ is exclusively electrical or a mixture of electrical and chemical.

In conclusion we identify a role after training for synaptic output from the GABAergic APL neurons [10, 11]. APL neurons appear to be specifically required for labile memory and not for consolidation of long-term memory. APL and DPM neurons are functionally connected yet outside of labile memory described here, disrupting either neuron can have different consequences. Firstly, reducing GABA synthesis in APL neurons enhances learning [11] whereas DPM neurons are not required during acquisition [6, 8]. Functional imaging data suggests that learning specifically increases DPM neuron activity but reduces APL activity driven by the conditioned odor [7, 11]. We suspect these differences relate to APL also having processes in the MB calyx, where GRASP suggests APL directly contacts MB neurons (Figure S4). Secondly, APL neurons are only required for earlier labile memory whereas DPM neurons are required for labile and consolidated memory. We suspect this reflects the mode and function of their respective transmitters. We propose that APL provides broad non-selective cross inhibition to maintain synaptic specificity in the recurrent DPM-MB-APL circuit that was originally set by the conditioned odor at acquisition. DPM in contrast might return activity to MB α′β′ neurons and supply consolidating signals to MB αβ neurons (see model in Figure S3). We expect additional neurons will contribute to the network and await identification. It will also be important to gain exclusive control of APL neurons.

Active memory storage is thought of mostly on a seconds to minute time scale in mammals [1, 2]. ASM in Drosophila suggests a prolonged duration active memory system. It will be important to determine the physiological property that is `held' in the putative recurrent network. A step-change in membrane potential accompanies periods of persistent activity in the oculomotor neural integrator of the goldfish [34]. Such a change in the MB neurons coding olfactory memory would render them more easily excited by the conditioned odorant. Physiology will be needed for us to definitively add ASM in Drosophila to goldfish gaze stabilization [34] and head direction [35], and prefrontal cortical circuits [1, 4] in mammals, as models to understand how memory is stored as persistent activity in recurrent neural networks. Nevertheless, the architecture and prolonged requirement for neurotransmission within the MB-DPM-APL neural circuit are suggestive. In addition, a recent gene profiling study of developing vertebrate cortex and annelid MB indicated a common evolutionary origin [36].

Experimental Procedures

Fly strains

Fly stocks were raised on standard cornmeal food at 25°C and 60% relative humidity. The wild-type strain is Canton-S. The c316, GH146, NP225, NP2631 and NP5288 GAL4 and uas-mCD8∷GFP strains are described [10, 21, 26, 37]. The uas-shits1 flies [25] carry an insertion on the third chromosome. The ChaGAL80 strain is that described in [11] and was provided by Ronald Davis (Scripps Florida), GH146QF, QUAS-mCD8∷GFP and uas-mCD8∷mCherry are described [29, 33]. The uas-Brp∷GFP transgene is described [31] and flies harboring uas-Brp∷GFP, and uas-mCD8∷mCherry were provided by Motojiro Yoshihara (UMass Medical School). 247-LexA∷VP16 flies were generated by screening hundreds of P-element transformation lines that carry the 247bp D-Mef2 MB enhancer (a gift from Ronald L. Davis) upstream of LexA∷VP16 [33]. L0111 flies expressing LexA in DPM neurons were a generous gift before publication from Ann-Shyn Chiang (National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan). The GRASP reporters lexAopmCD4∷spGFP11 and uas-mCD4∷spGFP1-10 are described [31] and were provided by Kristen Scott (UC Berkeley).

Behavioral analysis

For behavior experiments wild-type and uas-shits1 female flies were crossed to male flies harboring GH146, NP225, c316, NP2631, NP5288 or GH146;ChaGAL80, NP2631;ChaGAL80 or NP5288;ChaGAL80 flies. Mixed sex populations were tested together in all behavior experiments. Flies were food deprived for 18–20hr before training in milk bottles containing a damp filter paper. The olfactory appetitive paradigm was performed as described [22]. Odors were 3-octanol (7μl in 8ml mineral oil) or 4-methylcyclohexanol (15μl in 8ml mineral oil). Following training, flies were transferred into pre-warmed vials containing damp filter paper and stored in a temperature controlled room or incubator at 31°C for 2hr. For 3hr memory experiments, vials were returned to 23°C for 1hr before testing. For permissive temperature experiments flies were kept at 23°C at all times. For permissive temperature experiments incorporating cold-shock, flies were trained and kept at the permissive temperature for 2hr, cold-shocked for 2 min and tested at 3hr or 24hr. For restrictive temperature experiments flies were trained at 23°C, shifted to the restrictive temperature for 105 minutes, returned to permissive temperature, and cold-shocked 15 minutes later. The Performance Index (PI) was calculated as the number of flies in the arm containing the conditioned odor minus the number of flies in that with the unconditioned odor divided by the total number of flies in the experiment. A single PI value is the average score from flies of the identical genotype tested with each odor. Olfactory acuity was performed according to [8]. The odor concentrations used for conditioning are not strongly aversive to naïve wild-type flies. Therefore we increased concentrations 5-fold for acuity experiments. Flies were stored in vials with damp filter paper for 2hr at 31°C and shifted to 23°C for 1 hr prior to testing (Table S1). Sugar seeking motivation was performed using a procotol based on [38]. Flies were stored in vials with damp filter paper for 2hr at 31°C and shifted to 23°C for 1hr prior to testing. Flies were transferred to a t-maze and were allowed 2min to choose between an arm containing dry filter paper and an arm containing dry filter paper soaked with a 3M sucrose solution. Odorless air was pulled through the t-maze. Scores were calculated as for a Performance Index.

Statistical analyses were performed using PRISM (GraphPad Software). Overall analyses of variance (ANOVA) were followed by planned pairwise comparisons between the relevant groups with a Tukey HSD post-hoc test. In Figure 3B, a Mann-Whitney U test was used to evaluate whether the GH146GAL4; uas-shits1 + cold score was statistically different from zero. Unless otherwise stated, all n≥8 trials per genotype.

Imaging

To visualize native GFP or mCherry adult female flies were collected 4–9 days after eclosion (1 day for GRASP flies) and brains were dissected in ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde solution in PBS [1.86 mM NaH2PO4, 8.41 mM Na2HPO4, 175 mM NaCl] and fixed for an additional 60–120min at room temperature under vacuum. Samples were washed 3×10min with PBS containing 0.1% Triton-X100 (PBT), and 2× in PBS before mounting in Vectashield (Vector Labs).

Imaging was performed on a Zeiss LSM 510 Pascal confocal microscope and images were processed in AMIRA 5.2 (Mercury Systems). In some cases, debris on the brain surface and/or antennal and gustatory nerves was manually deleted from the relevant confocal sections to permit construction of a clear projection view of the z-stack. Reconstruction of neurons was performed in AMIRA 5.2, including an add-on described previously [39]. Brain neuropil surfaces were taken and slightly modified from [40].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Monika Chitre for assistance with data collection, and Motojiro Yoshihara, Chris Potter, Ron Davis, Kristin Scott, and the Bloomington Stock Centre for reagents. We are especially grateful to Ann-Shyn Chiang and Glenn Turner for communicating results and reagents prior to publication. This work was supported by an NIH MH09883 grant to S.W.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Goldman-Rakic PS. Cellular basis of working memory. Neuron. 1995;14:477–485. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang XJ. Synaptic reverberation underlying mnemonic persistent activity. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:455–463. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01868-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Compte A. Computational and in vitro studies of persistent activity: edging towards cellular and synaptic mechanisms of working memory. Neuroscience. 2006;139:135–151. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Douglas RJ, Martin KA. Recurrent neuronal circuits in the neocortex. Curr Biol. 2007;17:R496–500. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krashes MJ, Keene AC, Leung B, Armstrong JD, Waddell S. Sequential use of mushroom body neuron subsets during drosophila odor memory processing. Neuron. 2007;53:103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keene AC, Stratmann M, Keller A, Perrat PN, Vosshall LB, Waddell S. Diverse odor-conditioned memories require uniquely timed dorsal paired medial neuron output. Neuron. 2004;44:521–533. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu D, Keene AC, Srivatsan A, Waddell S, Davis RL. Drosophila DPM neurons form a delayed and branch-specific memory trace after olfactory classical conditioning. Cell. 2005;123:945–957. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keene AC, Krashes MJ, Leung B, Bernard JA, Waddell S. Drosophila dorsal paired medial neurons provide a general mechanism for memory consolidation. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1524–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krashes MJ, Waddell S. Rapid consolidation to a radish and protein synthesis-dependent long-term memory after single-session appetitive olfactory conditioning in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3103–3113. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5333-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka NK, Tanimoto H, Ito K. Neuronal assemblies of the Drosophila mushroom body. J Comp Neurol. 2008;508:711–755. doi: 10.1002/cne.21692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu X, Davis RL. The GABAergic anterior paired lateral neuron suppresses and is suppressed by olfactory learning. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:53–59. doi: 10.1038/nn.2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tully T, Quinn WG. Classical conditioning and retention in normal and mutant Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Physiol [A] 1985;157:263–277. doi: 10.1007/BF01350033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tempel BL, Bonini N, Dawson DR, Quinn WG. Reward learning in normal and mutant Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:1482–1486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.5.1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubnau J, Grady L, Kitamoto T, Tully T. Disruption of neurotransmission in Drosophila mushroom body blocks retrieval but not acquisition of memory. Nature. 2001;411:476–480. doi: 10.1038/35078077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGuire SE, Le PT, Davis RL. The role of Drosophila mushroom body signaling in olfactory memory. Science. 2001;293:1330–1333. doi: 10.1126/science.1062622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heisenberg M. Mushroom body memoir: from maps to models. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:266–275. doi: 10.1038/nrn1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crittenden JR, Skoulakis EM, Han KA, Kalderon D, Davis RL. Tripartite mushroom body architecture revealed by antigenic markers. Learn Mem. 1998;5:38–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folkers E, Drain P, Quinn WG. Radish, a Drosophila mutant deficient in consolidated memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8123–8127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tully T, Preat T, Boynton SC, Del VM. Genetic dissection of consolidated memory in Drosophila. Cell. 1994;79:35–47. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwaerzel M, Jaeckel A, Mueller U. Signaling at A-kinase anchoring proteins organizes anesthesia-sensitive memory in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1229–1233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4622-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waddell S, Armstrong JD, Kitamoto T, Kaiser K, Quinn WG. The amnesiac gene product is expressed in two neurons in the Drosophila brain that are critical for memory. Cell. 2000;103:805–813. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00183-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamura T, Chiang AS, Ito N, Liu HP, Horiuchi J, Tully T, Saitoe M. Aging specifically impairs amnesiac-dependent memory in Drosophila. Neuron. 2003;40:1003–1011. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00732-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keene AC, Waddell S. Drosophila olfactory memory: single genes to complex neural circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:341–354. doi: 10.1038/nrn2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu D, Akalal DB, Davis RL. Drosophila alpha/beta mushroom body neurons form a branch-specific, long-term cellular memory trace after spaced olfactory conditioning. Neuron. 2006;52:845–855. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitamoto T. Conditional modification of behavior in Drosophila by targeted expression of a temperature-sensitive shibire allele in defined neurons. J Neurobiol. 2001;47:81–92. doi: 10.1002/neu.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thum AS, Jenett A, Ito K, Heisenberg M, Tanimoto H. Multiple memory traces for olfactory reward learning in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11132–11138. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2712-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okada R, Awasaki T, Ito K. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-mediated neural connections in the Drosophila antennal lobe. J Comp Neurol. 2009;514:74–91. doi: 10.1002/cne.21971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chance FS, Abbott LF. Divisive inhibition in recurrent networks. Network. 2000;11:119–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Potter CJ, Tasic B, Russler EV, Liang L, Luo L. The Q system: a repressible binary system for transgene expression, lineage tracing, and mosaic analysis. Cell. 2010;141:536–548. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feinberg EH, Vanhoven MK, Bendesky A, Wang G, Fetter RD, Shen K, Bargmann CI. GFP Reconstitution Across Synaptic Partners (GRASP) defines cell contacts and synapses in living nervous systems. Neuron. 2008;57:353–363. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordon MD, Scott K. Motor control in a Drosophila taste circuit. Neuron. 2009;61:373–384. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagh DA, Rasse TM, Asan E, Hofbauer A, Schwenkert I, Durrbeck H, Buchner S, Dabauvalle MC, Schmidt M, Qin G, et al. Bruchpilot, a protein with homology to ELKS/CAST, is required for structural integrity and function of synaptic active zones in Drosophila. Neuron. 2006;49:833–844. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lai SL, Lee T. Genetic mosaic with dual binary transcriptional systems in Drosophila. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:703–709. doi: 10.1038/nn1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aksay E, Gamkrelidze G, Seung HS, Baker R, Tank DW. In vivo intracellular recording and perturbation of persistent activity in a neural integrator. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:184–193. doi: 10.1038/84023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taube JS, Bassett JP. Persistent neural activity in head direction cells. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13:1162–1172. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tomer R, Denes AS, Tessmar-Raible K, Arendt D. Profiling by image registration reveals common origin of annelid mushroom bodies and vertebrate pallium. Cell. 2010;142:800–809. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron. 1999;22:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colomb J, Kaiser L, Chabaud MA, Preat T. Parametric and genetic analysis of Drosophila appetitive long-term memory and sugar motivation. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:407–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmitt S, Evers JF, Duch C, Scholz M, Obermayer K. New methods for the computer-assisted 3-D reconstruction of neurons from confocal image stacks. Neuroimage. 2004;23:1283–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rein K, Zockler M, Mader MT, Grubel C, Heisenberg M. The Drosophila standard brain. Curr Biol. 2002;12:227–231. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00656-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.