Abstract

Riemerella anatipestifer (Hendrickson and Hilbert 1932) Segers et al. 1993 is the type species of the genus Riemerella, which belongs to the family Flavobacteriaceae. The species is of interest because of the position of the genus in the phylogenetic tree and because of its role as a pathogen of commercially important avian species worldwide. This is the first completed genome sequence of a member of the genus Riemerella. The 2,155,121 bp long genome with its 2,001 protein-coding and 51 RNA genes consists of one circular chromosome and is a part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project.

Keywords: capnophilic, non-motile, Gram-negative, poultry pathogen, mesophilic, chemoorganotrophic, Flavobacteriaceae, GEBA

Introduction

No strain designation has been published for the type strain of Riemerella anatipestifer; therefore it will be referred to in this publication as ATCC 11845T, after the earliest known deposit (= DSM 15868 = ATCC 11845 = JCM 9532). Strain ATCC 11845T is the type strain of R. anatipestifer which is the type species of the genus Riemerella. The organism was described for the first time by Hendrickson and Hilbert in 1932 as 'Pfeifferella anatipestifer' [1], was subsequently known as 'Pasteurella anapestifer' [2] and renamed by Bruner and Fabricant in 1954 as Moraxella anatipestifer [3,4]. However, since the organism is closely related to neither the genus Moraxella nor to Pasteurella [5] it was reclassified as a novel genus by Segers et al. in 1993 [6]. The reclassification was confirmed by subsequent 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis [7,8]. The generic name was given in honor to Riemer, who first described R. anatipestifer infections in geese in 1904 and referred to the disease as septicemia anserum exsudativa [9]. The species epithet is derived from the Latin noun 'anas/atis' meaning 'duck', and the Latin adjective 'pestifer' meaning 'pestilence-carrying' referring to the pathogenic effect the species has on water-fowl, especially ducks. The type strain of the species was isolated from blood of ducklings on Long Island, New York, and identified by Bruner in 1954 [3]. Further isolates were obtained from all kinds of avian hosts, however, pigeons and mammals are not infected by this species. R. anatipestifer is distributed worldwide and causes serious problems in agricultural flocks of duck, goose and turkey [10], but it has also been found in the upper respiratory tract of clinically healthy birds [7]. There is no indication that the organism can survive outside of its host. Currently, there are two species in the genus Riemerella. The only other validly published species of the genus is R. columbina which is mainly associated with respiratory disease in pigeons [11]. Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for R. anatipestifer ATCC 11845T, together with the description of the complete genomic sequencing and annotation.

Classification and features

A representative genomic 16S rRNA sequence from strain ATCC 11845T was compared using NCBI BLAST under default settings (e.g., considering only the high-scoring segment pairs (HSPs) from the best 250 hits) with the most recent release of the Greengenes database [12] and the relative frequencies, weighted by BLAST scores, of taxa and keywords (reduced to their stem [13]) were determined. The five most frequent genera were Riemerella (79.2%), Chryseobacterium (17.1%), Bergeyella (2.6%), “Rosa” (0.6%; misnomer) and Cloacibacterium (0.5%) (166 hits in total). Regarding the 124 hits to sequences from members of the species, the average identity within HSPs was 99.5%, whereas the average coverage by HSPs was 95.2%. Among all other species, the one yielding the highest score was “Rosa chinensis”, apparently a severe misannotation, which corresponded to an identity of 99.8% and an HSP coverage of 91.9%. The highest-scoring environmental sequence was EF219033 ('structure and significance Rhizobiales biofouling biofilms on reverse osmosis membrane treating MBR effluent clone RO224'), which showed an identity of 96.0% and a HSP coverage of 97.8%. The five most frequent keywords within the labels of environmental samples which yielded hits were 'skin' (10.3%), 'human' (4.9%), 'biota, cutan, lesion, psoriat' (4.0%) and 'fossa' (4.0%) (84 hits in total). Environmental samples which yielded hits of a higher score than the highest scoring species were not found.

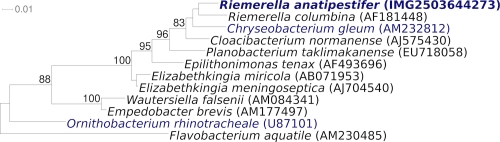

Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of R. anatipestifer in a 16S rRNA based tree. The sequences of the three identical 16S rRNA gene copies in the genome differ by one nucleotide from the previously published 16S rRNA sequence (U60101).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of R. anatipestifer relative to a selection of the other type strains within the family Flavobacteriaceae. The tree was inferred from 1,391 aligned characters [14,15] of the 16S rRNA gene sequence under the maximum likelihood criterion [16] and rooted with the type strain of the family Flavobacteriaceae. The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site. Numbers above branches are support values from 750 bootstrap replicates [17] if larger than 60%. Lineages with type strain genome sequencing projects registered in GOLD [18] are shown in blue, published genomes in bold.

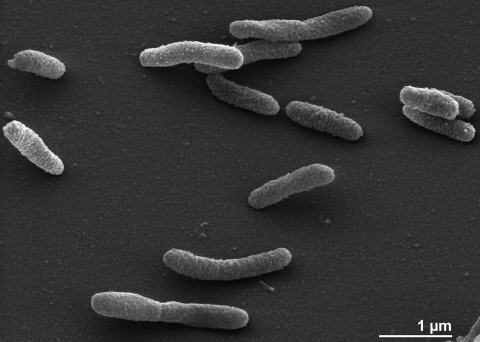

The cells of R. anatipestifer are generally rod-shaped (0.3-0.5 × 1.0-2.5 µm) with round ends (Figure 2) [6]. R. anatipestifer is a Gram-negative, non spore-forming bacterium (Table 1). The organism is described as non-motile. Gliding motility is not observed. Only three genes associated with motility have been found in the genome (see below). The organism is a capnophilic chemoorganotroph which prefers microaerobic conditions for growth. The optimum temperature for growth is 37°C, most strains can grow at 45°C but not at 4°C. Catalase and oxidase are present, thiamine is required for growth [6]. R. anatipestifer is not able to reduce nitrate and does not produce hydrogen sulfide. The organism tolerates 10% bile in serum but no growth occurs on agar containing 40% bile in serum [6]. Many biochemical reactions are negative or strain-dependent: Hinz et al. have stated that “R. anatipestifer is not easy to identify because it is characterized more by the absence than by the presence of specific biochemical properties” [31]. The organism has proteolytic activity but its capacity to utilize carbohydrates is strain-dependent and has been discussed controversially. It has been described that carbohydrates are used oxidatively and that R. anatipestifer is able to produce acid from glucose and maltose, less often from fructose, dextrin, mannose, trehalose, inositol, arabinose and rhamnose [31]. The production of indole is strain-dependent; the type strain does not produce indole [6]. Esculin is not hydrolyzed by most R. anatipestifer strains, a trait useful for distinguishing these strains from R. columbina strains [32]. Strain ATCC 11845T exhibits positive reactions for alkaline and acid phosphatase, ester lipase C8, leucine arylamidase, valine arylamidase, cystine arylamidase, phophoamidase, α-glucosidase and esterase C4. It does not produce α- and β-galactosidases, β-glucuronidase, β-glucosidase, α-mannosidase, β-glucosaminidase, lipase C14, fucosidase, trypsin, ornithine and lysine decarboxylases and phenylalanine deaminase [6].

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of R. anatipestifer ATCC 11845T

Table 1. Classification and general features of R. anatipestifer ATCC 11845T according to the MIGS recommendations [19].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [20] | |

| Phylum Bacteroidetes | TAS [21,22] | ||

| Class 'Flavobacteria' | TAS [21,23] | ||

| Order 'Flavobacteriales' | TAS [21,24] | ||

| Family Flavobacteriaceae | TAS [21,25-28] | ||

| Genus Riemerella | TAS [6,11] | ||

| Species Riemerella anatipestifer | TAS [6] | ||

| Type strain ATCC 11845 | NAS | ||

| Gram stain | negative | TAS [3] | |

| Cell shape | rod-shaped with rounded ends, single or in pairs | TAS [3] | |

| Motility | non-motile | TAS [3] | |

| Sporulation | none | TAS [6] | |

| Temperature range | mesophile | TAS [6] | |

| Optimum temperature | 37°C | TAS [3] | |

| Salinity | normal | NAS | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | microaerobic | TAS [3] |

| Carbon source | proteins | TAS [6] | |

| Energy source | chemoorganotroph | TAS [6] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | waterfowl and other birds | TAS [6] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | symbiotic | TAS [6] |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | septicemia | TAS [6] |

| Biosafety level | 2 | TAS [29] | |

| Isolation | duck blood | TAS [3] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Long Island, New York, USA | TAS [3] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | 1954 | TAS [3] |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | not reported | |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | not reported | |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | not reported | |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | not reported |

Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay (first time in publication); TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from of the Gene Ontology project [30]. If the evidence code is IDA, then the property was directly observed by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements.

R. anatipestifer is generally susceptible to enrofloxacin, amoxicillin, chloramphenicol, novobiocin, spiramycin, lincomycin and tetracyclines. Antibiotic resistance of the organism is steadily increasing: resistance to penicillin G, streptomycin and sulfonamides has been reported and more than 90% of all strains are resistant to polymyxin B, colistin, gentamycin, neomycin and kanamycin [33]. The transmission of R. anatipestifer in ducks occurs vertically through the egg as well as horizontally via the respiratory route. The disease affects primarily young ducks where it typically involves the respiratory tract and nervous system. Ocular and nasal discharge are often typical for the onset of the disease, lameness can be observed at a later state. The mortality ranges between 1 and 10%, surviving animals may be stunted [34,35]. Vaccination of flocks has proven a valuable course of protection, however, immunity is serovar-specific and more than 20 serovars of R. anatipestifer are known [36]. It is remarkable that R. anatipestifer persists post-infection on duck farms; biofilm formation of the organism is discussed as one possible explanation [37].

Chemotaxonomy

Few data are available for R. anatipestifer strain ATCC 11845T. The sole respiratory quinone found in this species is menaquinone [38]. Which specific quinone is present in R. anatipestifer remains unclear from the literature: whereas Segers et al. specify menaquinone 7 as sole respiratory quinone in the type strain [6], Vancanneyt et al. claim menaquinone 6 is the major respiratory quinone of the type species [11]. Typically, representatives of the genus Riemerella contain branched-chain fatty acids in high percentages. Major fatty acids of R. anatipestifer are iso-C15:0 (50-60%), iso-C13:0 (15-20%), 3-hydroxy iso-C17:0 (13-18%), 3-hydroxy anteiso-C15:0 (8-11%) and anteiso-C15:0 (6-8%) [6].

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its phylogenetic position [39], and is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project [40]. The genome project is deposited in the Genomes On Line Database [18] and the complete genome sequence is deposited in GenBank. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Three genomic libraries: one 454 pyrosequence standard library, one 454 PE library (14 kb insert size), one Illumina library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | Illumina GAii, 454 GS FLX Titanium |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 431 × Illumina; 77.6 × pyrosequence |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler version 2.3, Velvet 0.7.63, phrap SPS - 4.24 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal 1.4, GenePRIMP |

| INSDC ID | CP002346 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | December 2, 2010 | |

| GOLD ID | Gc01548 | |

| NCBI project ID | 41989 | |

| Database: IMG-GEBA | 2503538031 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 15868 |

| Project relevance | Tree of Life, GEBA |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

R. anatipestifer ATCC 11845T, DSM 15868, was grown microaerobically in DSMZ medium 535 (Trypticase Soy Broth Medium) [41] at 37°C. DNA was isolated from 0.5-1 g of cell paste using MasterPure Gram-positive DNA purification kit (Epicentre MGP04100) following the standard protocol as recommended by the manufacturer, with modification st/DL for cell lysis as described in Wu et al. [40]. DNA is available through the DNA Bank Network [42].

Genome sequencing and assembly

The draft genome was generated at the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI) using a combination of Illumina and 454 technologies (Roche). For this genome, we constructed and sequenced an Illumina GAii shotgun library which generated 26,937,600 reads totaling 969.8 Mb, a 454 Titanium standard library which generated 238,617 reads and a paired end 454 library with an average insert size of 14.3 kb which generated 112,671 reads totaling 141.8 Mb of 454 data. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing performed at the JGI can be found at [43]. The initial draft assembly contained 28 contigs in one scaffold. The 454 Titanium standard data and the 454 paired end data were assembled together with Newbler, version 2.3. The Newbler consensus sequences were computationally shredded into 2 kb overlapping fake reads (shreds). Illumina sequencing data was assembled with VELVET, version 0.7.63 [44], and the consensus sequences were computationally shredded into 1.5 kb overlapping fake reads (shreds). We integrated the 454 Newbler consensus shreds, the Illumina VELVET consensus shreds and the read pairs in the 454 paired end library using parallel phrap, version SPS - 4.24 (High Performance Software, LLC). The software Consed [45] was used in the following finishing process. Illumina data was used to correct potential base errors and increase consensus quality using the software Polisher developed at JGI [46]. Possible mis-assemblies were corrected using gapResolution [43], Dupfinisher [47], or sequencing cloned bridging PCR fragments with subcloning. Gaps between contigs were closed by editing in Consed, by PCR and by Bubble PCR (J-F Cheng, unpublished) primer walks. A total of 388 additional reactions were necessary to close gaps and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. The error rate of the completed genome sequence is less than 1 in 100,000. Together, the combination of the Illumina and 454 sequencing platforms provided 508.6 × coverage of the genome.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [48] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline, followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePRIMP pipeline [49]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGR-Fam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. Additional gene prediction analysis and functional annotation was performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes - Expert Review (IMG-ER) platform [50].

Genome properties

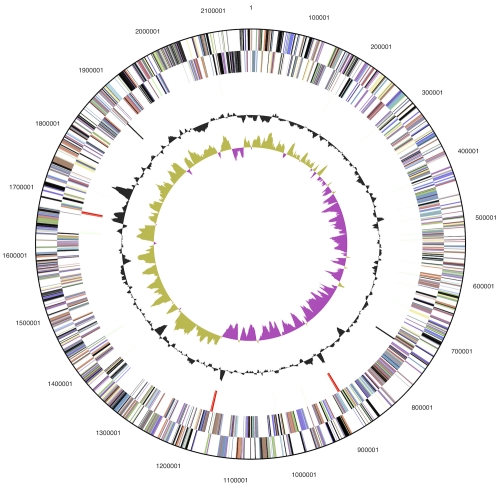

The genome consists of a 2,155,121 bp long chromosome with a G+C content of 35.0% (Table 3 and Figure 3). Of the 2,052 genes predicted, 2,001 were protein-coding genes, and 51 RNAs; 29 pseudogenes were also identified. The majority of the protein-coding genes (64.1%) were assigned with a putative function while the remaining ones were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 2,155,121 | 100.00% |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 1,948,611 | 90.42% |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 754,510 | 35.01% |

| Number of replicons | 1 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 0 | |

| Total genes | 2,052 | 100.00% |

| RNA genes | 51 | 2.49% |

| rRNA operons | 3 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 2,001 | 97.51% |

| Pseudo genes | 29 | 1.41% |

| Genes with function prediction | 1,316 | 64.10% |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 125 | 6.09% |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 1,283 | 64.13% |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 1,411 | 68.76% |

| Genes with signal peptides | 472 | 23.00% |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 414 | 20.18% |

| CRISPR repeats | 2 |

Figure 3.

Graphical circular map of the chromosome. From outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | value | %age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 133 | 9.7 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 0 | 0.0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 70 | 5.1 | Transcription |

| L | 92 | 6.7 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 0 | 0.0 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 19 | 1.4 | Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| Y | 0 | 0.0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 22 | 1.6 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 32 | 2.3 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 139 | 10.2 | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis |

| N | 3 | 0.2 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0.0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 26 | 1.9 | Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport |

| O | 66 | 4.8 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 77 | 5.6 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 39 | 2.9 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 101 | 7.4 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 52 | 3.8 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 83 | 6.1 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 56 | 4.1 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 88 | 6.4 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 20 | 1.5 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 159 | 11.6 | General function prediction only |

| S | 89 | 6.5 | Function unknown |

| - | 769 | 37.5 | Not in COGs |

Acknowledgements

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the help of Sabine Welnitz (DSMZ) for growing R. anatipestifer cultures. This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program, and by the University of California, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344, and Los Alamos National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-06NA25396, UT-Battelle and Oak Ridge National Laboratory under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725, as well as German Research Foundation (DFG) INST 599/1-2.

References

- 1.Hendrickson JM, Hilbert KF. A new and serious septicemic disease of young ducks with a description of the causative organism, Pfeifferella anatipestifer. Cornell Vet 1932; 22:239-252 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hauduroy, et al Pasteurella anapestifer Dict. d. Bact. Path. 2e ed. 1953, p367 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruner DW, Fabricant J. A strain of Moraxella anatipestifer (Pfeifferella anatipestifer) isolated from ducks. Cornell Vet 1954; 44:461-464 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved Lists of Bacterial Names. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980; 30:225-420 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossau R, Van Landschoot A, Gillis M, De Ley J. Taxonomy of Moraxellaceae fam. nov., a new bacterial family to accommodate the genera Moraxella, Acinetobacter, and Psychrobacter and related organisms. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1991; 41:310-319 10.1099/00207713-41-2-310 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Segers P, Mannheim W, Vancanneyt M, De Brandt K, Hinz KH, Kersters K, Vandamme P. Riemerella anatipestifer gen. nov., comb. nov., the causative agent of septicemia anserum exsudativa, and its phylogenetic affiliation within the Flavobacterium-Cytophaga rRNA homology group. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1993; 43:768-776 10.1099/00207713-43-4-768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryll M, Christensen H, Bisgaard M, Christensen JP, Hinz KH, Köhler B. Studies on the prevalence of Riemerella anatipestifer in the upper respiratory tract of clinically healthy ducklings and characterization of untypable strains. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health 2001; 48:537-546 10.1046/j.1439-0450.2001.00471.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Subramaniam S, Chua KL, Tan HM, Loh H, Kuhnert P, Frey J. Phylogenetic position of Riemerella anatipestifer based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:562-565 10.1099/00207713-47-2-562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riemer O. Kurze Mitteilung über eine bei Gänsen beobachtete exsudative Septikämie und deren Erreger. Zentbl Bakteriol I Abt Orig 1904; 37:641-648 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metzner M, Köhler-Repp D, Köhler B. Riemerella anatipestifer infections in turkey and other poultry. 7th International Symposium on Turkey Diseases 2008. p117-122 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vancanneyt M, Vandamme P, Segers P, Torck U, Coopman R, Kersters K, Hinz KH. Riemerella columbina sp. nov., a bacterium associated with respiratory disease in pigeons. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1999; 49:289-295 10.1099/00207713-49-1-289 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, Huber T, Dalevi D, Hu P, Andersen GL. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006; 72:5069-5072 10.1128/AEM.03006-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porter MF. An algorithm for suffix stripping. Program: electronic library and information systems 1980; 14:130-137 10.1108/eb046814 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee C, Grasso C, Sharlow MF. Multiple sequence alignment using partial order graphs. Bioinformatics 2002; 18:452-464 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 2000; 17:540-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML Web servers. Syst Biol 2008; 57:758-771 10.1080/10635150802429642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pattengale ND, Alipour M, Bininda-Emonds ORP, Moret BME, Stamatakis A. How many bootstrap replicates are necessary? Lect Notes Comput Sci 2009; 5541:184-200 10.1007/978-3-642-02008-7_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liolios K, Chen IM, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Hugenholtz P, Markowitz VM, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2009: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2009; 38:D346-D354 10.1093/nar/gkp848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piechulla K, Pohl S, Mannheim W. Phenotypic and genetic relationships of so-called Moraxella (Pasteurella) anatipestifer to the Flavobacterium/Cytophaga group. Vet Microbiol 1986; 11:261-270 10.1016/0378-1135(86)90028-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garrity GM, Holt JG. The Road Map to the Manual. In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 1, Springer, New York, 2001, p. 119-169. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ludwig W, Euzeby J, Whitman WG. Draft taxonomic outline of the Bacteroidetes, Planctomycetes, Chlamydiae, Spirochaetes, Fibrobacteres, Fusobacteria, Acidobacteria, Verrucomicrobia, Dictyoglomi, and Gemmatimonadetes http://www.bergeys.org/outlines/Bergeys_Vol_4_Outline.pdf Taxonomic Outline 2008.

- 24.Garrity GM, Holt JG. Taxonomic Outline of the Archaea and Bacteria In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 1, Springer, New York, 2001, p. 155-166. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Validation of the publication of new names and new combinations previously effectively published outside the IJSB. List No. 41. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1992; 42:327-328 10.1099/00207713-42-2-327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reichenbach H. Order 1. Cytophagales Leadbetter 1974, 99AL. In: Holt JG (ed), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, First Edition, Volume 3, The Williams and Wilkins Co., Baltimore, 1989, p. 2011-2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernardet JF, Segers P, Vancanneyt M, Berthe F, Kersters K, Vandamme P. Cutting a Gordian knot: emended classification and description of the genus Flavobacterium, emended description of the family Flavobacteriaceae, and proposal of Flavobacterium hydatis nom. nov. (Basonym, Cytophaga aquatilis Strohl and Tait 1978). Int J Syst Bacteriol 1996; 46:128-148 10.1099/00207713-46-1-128 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernardet JF, Nakagawa Y, Holmes B. Proposed minimal standards for describing new taxa of the family Flavobacteriaceae, and emended description of the family. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2002; 52:1049-1070 10.1099/ijs.0.02136-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.BAuA Classification of bacteria and archaea in risk groups. TRBA 2005; 466:84 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hinz KH, Ryll M, Köhler B. Detection of acid production from carbohydrates by Riemerella anatipestifer and related organisms using the buffered single substrate test. Vet Microbiol 1998; 60:277-284 10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00187-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubbenstroth D, Hotzel H, Knobloch J, Teske L, Rautenschlein S, Ryll M. Isolation and characterization of atypical Riemerella columbina strains from pigeons and their differentiation from Riemerella anatipestifer. Vet Microbiol 2011; 147:103-112 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Köhler B, Heiss R, Albrecht K. 1995. Riemerella anatipestifer as pathogen for geese in the northern and central parts of Germany. p. 50-71. In Proceeding of the 49th Symposium on Poultry Diseases of the German Veterinary Medicine Society, Giessen, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vandamme P, Hafez HM, Hinz KH. Capnophilic bird pathogens in the family Flavobacteriaceae: Riemerella, Ornithobacterium and Coenonia, p. 695-708. In M. Dworkin, S. Falkow, E. Rosenberg, K.-H. Schleifer and E. Stackebrandt (ed.), The Prokaryotes, 3rd ed, vol 7. Springer, Singapore 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarver CF, Morishita TY, Nersessian B. The effect of route of inoculation and challenge dosage on Riemerella anatipestifer infection in Pekin ducks (Anas platyrhynchos). Avian Dis 2005; 49:104-107 10.1637/7248-073004R1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pathanasophon P, Sawada T, Pramoolsinsap T, Tanticharoenyos T. Immunogenicity of Riemerella anatipestifer broth culture bacterin and cell-free culture filtrate in ducks. Avian Pathol 1996; 25:705-719 10.1080/03079459608419176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu Q, Han X, Zhou X, Ding S, Ding C, Yu S. Characterization of biofilm formation by Riemerella anatipestifer. Vet Microbiol 2010; 144:429-436 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mannheim W, Pohl S, Holländer R. On the taxonomy of Actinobacillus, Haemophilus, and Pasteurella: DNA base composition, respiratory quinones, and biochemical reactions of representative collection cultures. Zbl Bakt Hyg, I. Abt Orig A 1980; 246:512-540 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klenk HP, Göker M. En route to a genome-based classification of Archaea and Bacteria? Syst Appl Microbiol 2010; 33:175-182 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu D, Hugenholtz P, Mavromatis K, Pukall R, Dalin E, Ivanova NN, Kunin V, Goodwin L, Wu M, Tindall BJ, et al. A phylogeny-driven genomic encyclopaedia of Bacteria and Archaea. Nature 2009; 462:1056-1060 10.1038/nature08656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.List of growth media used at DSMZ: http//www.dsmz.de/microorganisms/media_list.php

- 42.Gemeinholzer B, Dröge G, Zetzsche H, Haszprunar G, Klenk HP, Güntsch A, Berendsohn WG, Wägele JW. The DNA Bank Network: the start from a German initiative. Biopreservation and Biobanking 9: 51-55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.DOE Joint Genome Institute http://www.jgi.doe.gov/

- 44.Zerbino DR, Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res 2008; 18:821-829 10.1101/gr.074492.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phrap and Phred for Windows. MacOS, Linux, and Unix. http://www.phrap.com

- 46.Lapidus A, LaButti K, Foster B, Lowry S, Trong S, Goltsman E. POLISHER: An effective tool for using ultra short reads in microbial genome assembly and finishing. AGBT, Marco Island, FL, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Han C, Chain P. 2006. Finishing repeat regions automatically with Dupfinisher. In: Proceeding of the 2006 international conference on bioinformatics & computational biology. Arabina HR, Valafar H (eds), CSREA Press. June 26-29, 2006: 141-146. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hyatt D, Chen GL, LoCascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:119 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pati A, Ivanova NN, Mikhailova N, Ovchinnikova G, Hooper SD, Lykidis A, Kyrpides NC. GenePRIMP: a gene prediction improvement pipeline for prokaryotic genomes. Nat Methods 2010; 7:455-457 10.1038/nmeth.1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Markowitz VM, Ivanova NN, Chen IMA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]