Abstract

Transcription factor Oct4 is expressed in pluripotent cell lineages during mouse development, namely, in inner cell mass (ICM), primitive ectoderm, and primordial germ cells. Functional studies have revealed that Oct4 is essential for the maintenance of pluripotency in inner cell mass and for the survival of primordial germ cells. However, the function of Oct4 in the primitive ectoderm has not been fully explored. In this study, we investigated the role of Oct4 in mouse P19 embryonal carcinoma (EC) cells, which exhibit molecular and developmental properties similar to the primitive ectoderm, as an in vitro model. Knockdown of Oct4 in P19 EC cells upregulated several early mesoderm-specific genes, such as Wnt3, Sp5, and Fgf8, by activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Overexpression of Oct4 was sufficient to suppress Wnt/β-catenin signaling through its action as a transcriptional activator. However, Brachyury, a key regulator of early mesoderm development and a known direct target of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, was unable to be upregulated in the absence of Oct4, even with additional activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Microarray analysis revealed that Oct4 positively regulated the expression of Tdgf1, a critical component of Nodal signaling, which was required for the upregulation of Brachyury in response to Wnt/β-catenin signaling in P19 EC cells. We propose a model that Oct4 maintains pluripotency of P19 EC cells through 2 counteracting actions: one is to suppress mesoderm-inducing Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and the other is to provide competence to Brachyury gene to respond to Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Introduction

The POU family transcription factor Oct4 (encoded by Pou5f1) is specifically expressed in pluripotent cell lineages during mouse development. Oct4 is first expressed in all blastomeres at early cleavage stages. By the late blastocyst stage, Oct4 expression is restricted to the inner cell mass (ICM) and diminishes in the trophectoderm. Around the time of implantation, Oct4 expression persists in the primitive ectoderm but is downregulated in the primitive endoderm. When the primitive ectoderm differentiates into the 3 germ layers, Oct4 expression remains in the primordial germ cells (PGC), which emerge at the posterior end of the primitive streak [1–4]. Even though Oct4 is continuously expressed in these pluripotent cell lineages from ICM through the primitive ectoderm to PGC, its transcription is controlled by distinct mechanisms depending on the developmental stages. Specifically, the expression in ICM and PGC is activated by the distal enhancer (DE), whereas the expression in the primitive ectoderm is regulated by the proximal enhancer (PE) [5]. Oct4 is strongly expressed in various pluripotent cell lines, such as embryonic stem (ES), epiblast stem (EpiS), and embryonal carcinoma (EC) cells, and their expression levels are also controlled by distinct enhancers: DE drives the expression in ES and F9 EC cells, whereas PE drives the expression in EpiS and P19 EC cells [5–7]. The existence of 2 distinct mechanisms for transcriptional regulation implicates that Oct4 may play different roles depending on cell types or developmental stages.

Roles of Oct4 in ICM and ES cells, which is activated by DE, have been extensively investigated. Blastocysts derived from Oct4-null zygotes produce abnormal ICM that expresses trophectoderm-specific marker [8]. Likewise, the suppression of Oct4 in ES cells results in the differentiation of trophectoderm [9]. Thus, in ICM and ES cells, Oct4 is necessary to maintain pluripotency by preventing the formation of trophectoderm. One mechanism by which Oct4 prevents trophectoderm differentiation is to interfere with Cdx2, which is essential for the maintenance of trophectoderm lineage [10,11]. In ES cells, Oct4 directly binds to enhancer sequences of various pluripotency-associated genes, such as Sox2, Nanog, Utf1, Fbxo15, Lefty1, and Oct4 itself [12–14]. Thus, Oct4 functions as a master regulator of the pluripotency gene transcription network in ES cells, which is likely to be the molecular basis of its capacity to reprogram adult somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells [15].

Function of Oct4 in PGC, which is also driven by DE, has been investigated [16,17]. Conditional knockout of Oct4 in PGC results in apoptosis of PGC [16]. Chimera study shows that Oct4-deprived cells are able to express Ifitm3 (also known as Fragilis) and Prdm1 (also known as Blimp1), markers for PGC precursors, but are unable to express Dppa3 (also known as Stella), a marker for differentiated PGC [17]. Thus, Oct4 is critical for the differentiation and survival of PGC. Importantly, unlike ICM or ES cells, the suppression of Oct4 in PGC does not lead to the differentiation of trophectoderm [16,17], indicating that the roles of Oct4 are different between ICM and PGC.

In the present study, we investigated the role of Oct4 in P19 EC cells, which is driven by PE. P19 EC cells were originally isolated from teratocarcinoma of normal embryo origin, and possess the molecular and developmental characteristics similar to the primitive ectoderm [18,19]. Previously, we showed that in P19 EC cells, the initiation of mesoderm formation is dependent on Wnt3 and β-catenin, and that the activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is sufficient to upregulate the expression of various early mesoderm genes, including Brachyury [20]. Importantly, both Wnt3 and β-catenin are essential for the initiation of mesoderm formation in the primitive ectoderm of normal embryos, as demonstrated by knockout studies [21,22], which corroborates similarities between the primitive ectoderm and P19 EC cells. EpiS cells are pluripotent cell lines that are generated by culturing primitive ectoderm of normal embryos [6,7]. Although the properties of EpiS cells are close to the primitive ectoderm, their maintenance and experimental manipulations appear to be more difficult than many other cell lines, including P19 EC cells. For example, EpiS cells commit massive apoptosis upon cell dissociation [6,7]. In the present study, we take advantage of P19 EC cells, which are more stable and easier to manipulate than EpiS cells, as a model to investigate the function of Oct4 in the primitive ectoderm. Our study suggests that Oct4 regulates the maintenance of pluripotent state through 2 distinct mechanisms: one is to prevent the differentiation of mesoderm by interfering with Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and the other is to provide competence for the induction of Brachyury, a key transcription factor of mesoderm development.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

P19 EC cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were cultured in minimum essential medium (MEM)-α medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 2.5% fetal bovine serum and 7.5% calf serum. HEK293 cells (293-H; Invitrogen) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum. Mouse ES cells (a gift from Dr. Richard Allsopp, University of Hawaii) and ZHBTc4 cells (a gift from Dr. Hitoshi Niwa, RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology, Kobe, Japan) were cultured in ESGRO Complete Clonal Grade Medium (Millipore, Billerica, MA) without feeder cells. Recombinant mouse BMP4, SFRP1, and NOGGIN proteins (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were prepared according to the manufacturer's instruction. BIO ([2′Z,3′E]-6-bromoindirubin-3′-oxime) and SB431542 (EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at 10 and 20 mM as stocks, respectively.

Plasmids and transfection

The plasmids encoding nontarget shRNA, Oct4 shRNA, and β-catenin shRNA correspond to SHC002, TRCN0000009611, and TRCN0000012692, respectively (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). GFP expression construct (pEF/cyto/myc/GFP; Invitrogen), TOPFLASH (Upstate, Charlottesville, VA), FOPFLASH (Upstate), and pRL-TK (Promega, Madison, WI) were obtained commercially. Expression plasmids encoding Lrp5ΔN and β-catenin were described previously [23]. Expression plasmids encoding Oct4, Oct4-glucocorticoid receptor (GR), Oct4[V267P], Oct4ΔPOU, Oct4ΔHOM, EnR-Oct4, VP16-Oct4, Dkk1, and Gsk3b were generated, as described in Supplementary Data (available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd). For transfection, 2 × 104 cells were seeded in each well of 24-well plates, and plasmids were transfected on the following day using Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instruction. For overexpression studies, a total of up to 800 ng plasmid DNA was transfected for each well. For luciferase assays, 50 ng of pRL-TK and 150 ng of TOPFLASH or FOPFLASH together with other plasmids were transfected for each well. For knockdown studies, a total of 400 ng of shRNA-encoding plasmid was transfected for each well.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), washed in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (PBSw), and permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS. After blocking with 5% bovine serum albumin in PBSw, specimens were incubated in anti-OCT4 antibody (1/200, sc-5279; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) overnight at 4°C, washed in PBSw, and incubated in Alexa Fluor 488-anti-mouse antibody (1/500; Invitrogen) for 2 h at ambient room temperature. Actin filament was stained with Alexa Fluor 546-phalloidin (33 nM; Invitrogen). Nucleus was stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Invitrogen).

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction analysis

Total RNA was extracted using TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, OH). cDNA was synthesized from total RNA, using oligo dT(18) primer and M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega). Real-time PCR was performed using iCycler Thermal Cycler with MyiQ Single Color Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). cDNA was amplified using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) with the following condition: the initial denaturation at 94°C (5 min) followed by up to 45 cycles of 94°C (15 s), 60°C (20 s), and 72°C (40 s). The primer sequences for reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) are shown in Supplementary Data. Gapdh levels were used to normalize the expression levels of all other genes. Gapdh has been shown to be suitable as an internal standard for measuring RNA levels in ES cells regardless of their differentiation status [24]. Further, our study using the control and Oct4 knockdown P19 EC cells shows that the relative expression levels of other housekeeping genes, namely, EF1α and β-actin, were not different between the 2 sample groups (Table 1). Thus, it is likely that the Gapdh expression is relatively stable in P19 EC cells regardless of their differentiation status. All experiments were conducted using 3 independent sets of samples, and data are presented as average ± standard deviation.

Table 1.

Relative Expression Levels of Cell-Autonomous Negative Regulators of Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in Oct4-Knockdown P19 Cells

| |

|

|

Relative expression level (Oct4 shRNA/control shRNA) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene symbol | Reference | Agilent probe name | Microarray (Exp. 1–2) | qRT-PCRa(mean ± SD) |

| Gapdh | N/A | A_52_P1687 | 0.97–0.94 | N/A |

| A_52_P479958 | 0.96–0.96 | |||

| Eef1a1 | N/A | A_52_P299505 | 0.87–1.04 | 0.97 ± 0.21 |

| (EF1α) | A_51_P118765 | 0.99–1.03 | ||

| Actb | N/A | A_51_P173760 | 0.98–0.92 | 1.27 ± 0.16 |

| (β-actin) | A_51_P251154 | 1.16–1.17 | ||

| Gsk3a | [68] | A_51_P437279 | 1.05–1.23 | 0.97 ± 0.11 |

| Gsk3b | [68] | A_52_P641629 | 1.37–1.66 | 1.42 ± 0.16 |

| A_51_P514412 | 1.14–1.97 | |||

| Axin1 | [69] | A_52_P197007 | 1.21–1.36 | 1.37 ± 0.35 |

| Axin2 | [69] | A_52_P54176 | 1.10–1.18 | 0.80 ± 0.04 |

| Apc | [70] | A_52_P633752 | 1.22–1.20 | 1.33 ± 0.29 |

| A_51_P273378 | 1.89–2.07 | |||

| A_52_P284981 | 1.54–1.80 | |||

| A_52_P675171 | 1.37–1.76 | |||

| A_51_P469822 | 1.29–1.69 | |||

| Apc2 | [70] | A_51_P156708 | 0.99–0.97 | 0.42 ± 0.03 |

| Btrc | [71] | A_52_P98674 | 1.09–1.08 | 1.15 ± 0.11 |

| Ctnnbip1 | [72] | A_51_P335849 | 1.27–1.45 | 1.51 ± 0.29 |

| Cby1 | [73] | A_51_P470311 | 0.80–0.98 | 0.70 ± 0.10 |

| Tax1bp3 | [74] | A_51_P487384 | 1.14–1.29 | 2.34 ± 0.08 |

| Tle1 | [75] | A_52_P328044 | 0.63–0.62 | 0.58 ± 0.09 |

| A_51_P199716 | 0.68–0.80 | |||

| A_52_P330694 | 0.79–0.98 | |||

| Tle2 | [75] | A_51_P175303 | 2.87–1.67 | 2.40 ± 0.86 |

| Tle3 | [75] | A_52_P590740 | 0.78–0.88 | 0.88 ± 0.08 |

| A_51_P151003 | 1.11–0.95 | |||

| Tle4 | [75] | A_51_P346543 | 2.21–2.43 | 2.30 ± 0.39 |

| Tle6 | [75] | A_51_P368591 | 0.74–0.69 | 0.44 ± 0.17 |

| Aes | [75] | A_51_P243342 | 1.39–1.44 | 7.50 ± 1.88 |

Normalized with Gapdh.

qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction.

Dual-luciferase assay

Cells were transfected with TOPFLASH or FOPFLASH (150 ng/well) and pRL-TK (50 ng/well) together with other plasmids, and were lysed 24 h later for reporter analyses using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) with Gene Light 55 Luminometer (Microtech, Chiba, Japan). The total amount of transfected plasmids per well was adjusted to be equal among samples using a control plasmid. All experiments were conducted using 3 independent sets of samples, and data are presented as average ± standard deviation.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA was extracted from P19 EC cells that were transfected with Oct4 shRNA plasmid or control shRNA plasmid for 48 h. Seven hundred nanograms of each sample was used for probe synthesis using Quick-Amp one color labeling kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), which was hybridized to Whole Mouse Genome Microarray (G4122F; Agilent), according to the vendor's protocol. Signals were scanned using DNA 2-Color Microarray Scanner (G2565CA; Agilent), and analyzed with GeneSpring GX 11.0.1 software (Agilent). Data were exported to Microsoft Excel sheet (Supplementary Excel file). Experiment was conducted using 2 independent sets of transfected cells, presented as Experiment 1 and Experiment 2 in the Excel sheet.

Results

Response of P19 EC cells to BMP4 is similar to that of the primitive ectoderm

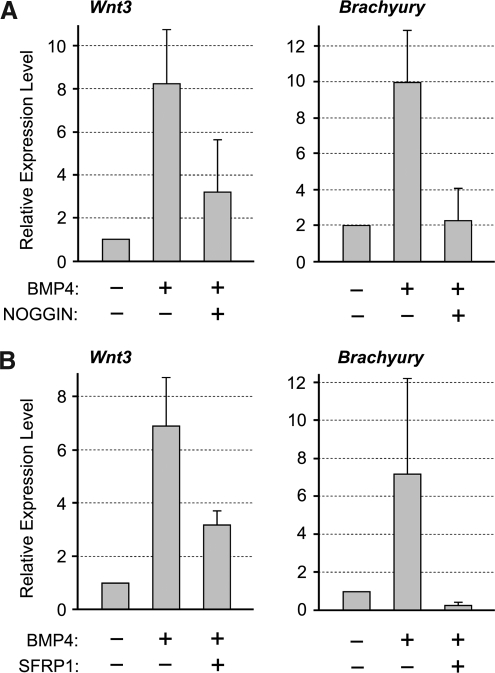

To further substantiate similarities between P19 EC cells and the primitive ectoderm, we examined responses of P19 EC cells to BMP4 treatment. BMP4 can replace serum in the culture medium to maintain self-renewal of mouse ES cells [25]. In contrast, incubation of primitive ectoderm explants with BMP4 results in the activation of primitive streak-specific genes, such as Wnt3 and Brachyury [26]. Thus, BMP4 suppresses differentiation in ES cells, whereas it induces differentiation of mesoderm in the primitive ectoderm. To determine whether P19 EC cells exhibit characteristics of the primitive ectoderm, we cultured them in the medium containing BMP4 for 24 h, and examined the expression levels of Wnt3 and Brachyury.

Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis showed that the expression levels of both Wnt3 and Brachyury were upregulated by BMP4 treatment in P19 EC cells (Fig. 1A). The activation was eliminated by cotreatment with NOGGIN protein, which binds BMP4 and prevents its interaction with the receptors [27], verifying that the activation of Wnt3 and Brachyury was specifically induced by the action of BMP4 (Fig. 1A). This indicates that the response of P19 EC cells to BMP4 treatment is similar to that of the primitive ectoderm rather than to that of ES cells. Our study further showed that the induction of Brachyury expression by BMP4 was mediated by the activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, because the induction was entirely abolished by the presence of SFRP1 protein (Fig. 1B), a secreted inhibitor of Wnt ligand [28]. In contrast, the induction of Wnt3 by BMP4 was only partly inhibited by SFRP1 (Fig. 1B). This suggests that the Wnt3 gene is activated by BMP4 through both Wnt-dependent and Wnt-independent mechanisms, the former of which is consistent with our previous finding that the transcription of Wnt3 is controlled by Wnt/β-catenin signaling through a positive-feedback mechanism [20].

FIG. 1.

Response of P19 EC cells to BMP4. (A) P19 EC cells are cultured in the presence or absence of BMP4 (0.5 μg/mL) and NOGGIN (1 μg/mL). (B) P19 EC cells are cultured in the presence or absence of BMP4 and SFRP1 (2.5 μg/mL). In both experiments, cells are cultured for 24 h and examined for the expression levels of Wnt3 and Brachyury by qRT-PCR. EC, embryonal carcinoma; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction.

Suppression of Oct4 results in activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in P19 EC cells

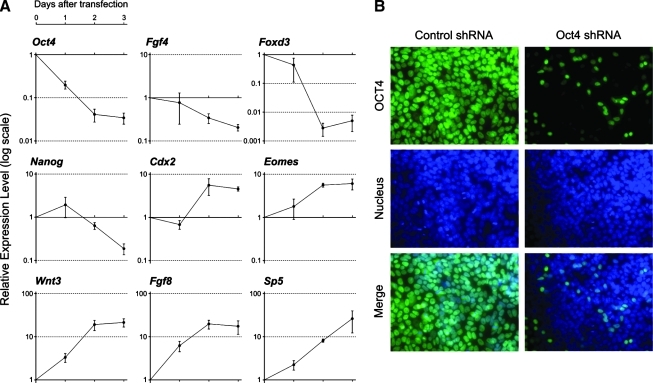

To investigate the roles of Oct4 in P19 EC cells, we suppressed its expression using a specific shRNA plasmid, and examined gene expression levels at 3 different time points, namely, 24, 48, and 72 h after transfection. As a control, the plasmid encoding nontarget shRNA, which does not match to any genes in the mouse genome, was transfected. The knockdown efficiency of Oct4-specific shRNA plasmid, as measured by qRT-PCR analysis of the endogenous Oct4 mRNA level, was about 80%, 96%, and 97% at 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively (Fig. 2A). The endogenous Oct4 protein was also markedly reduced by the transfection of Oct4-specific shRNA plasmid (Fig. 2B). Further, the genes that are known to be direct targets of Oct4, such as Fgf4 [29], Nanog [30], and Foxd3 [31], were downregulated by the knockdown of Oct4 (Fig. 2A), confirming effective suppression of the Oct4 activity.

FIG. 2.

Knockdown of Oct4 results in upregulation of primitive streak-specific genes in P19 EC cells. (A) Relative gene expression levels, as examined by qRT-PCR, in Oct4 shRNA-transfected cells in comparison to control shRNA-transfected cells at each time point. One day after transfection, cells are cultured with puromycin for 1 or 2 additional days. (B) Reduction of Oct4 protein by Oct4 shRNA plasmid 1 day after transfection, as examined immunocytochemically. Cells are fixed 1 day after transfection. Nucleus is observed with DAPI. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd.

We found that the expression of several genes that are normally expressed in the primitive streak, namely, Wnt3 [21], Sp5 [32], Fgf8 [33], Cdx2 [34], and Eomes [35], was upregulated by the knockdown of Oct4. The upregulation of Wnt3, Fgf8, and Sp5 was already evident by 24 h after transfection, whereas the downregulation of Fgf4 and Foxd3 was observed only after 48 h (Fig. 2A). This suggests that the activation of these primitive streak-specific genes occurs earlier than the downregulation of pluripotency-associated genes in response to the knockdown of Oct4 in P19 EC cells.

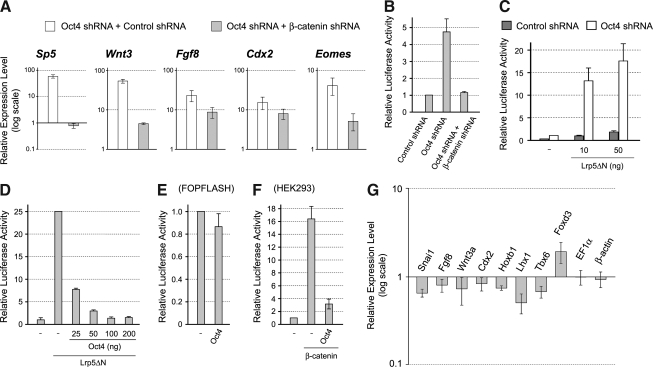

We previously showed that activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is sufficient to upregulate many primitive streak-specific genes, including Wnt3, Sp5, Cdx2, and Fgf8, in P19 EC cells [20]. Thus, we speculated that the knockdown of Oct4 first results in activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, which in turn upregulates the primitive streak-specific genes. To test this possibility, we simultaneously knocked down Oct4 and β-catenin, an essential component of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Activation of Sp5 by Oct4 knockdown was entirely abolished by simultaneous knockdown of β-catenin (Fig. 3A). Also, activation of Wnt3, Fgf8, Cdx2, and Eomes by Oct4 knockdown was partly diminished by simultaneous β-catenin knockdown (Fig. 3A). These results suggest that the activation of primitive streak-specific genes in response to Oct4 knockdown is in part mediated by the activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

FIG. 3.

Oct4 negatively regulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling in P19 EC cells. (A) The relative expression levels of primitive streak-specific genes in Oct4-knockdown cells in the presence or absence of β-catenin, as examined by qRT-PCR. One day after transfection, cells are cultured with puromycin for 1 additional day, followed by RNA extraction. (B) β-catenin-dependent activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling reporter in response to Oct4 knockdown. (C) Enhancement of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by Oct4 knockdown. The basal level of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is elevated by a constitutively active mutant form of Wnt coreceptor Lrp5ΔN. (D) Inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in a dose-dependent manner by overexpression of Oct4. (E) Overexpression of Oct4 does not impair the activity of FOPFLASH reporter. (F) Inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by overexpressing Oct4 in HEK293 cells. Wnt/β-catenin signaling is activated by the transfection of plasmid encoding β-catenin. In (B–F), cells are lysed for luciferase assay 1 day after plasmid transfection. (G) Upregulation of various mesoderm genes in 3-day aggregates is diminished by Oct4 overexpression.

To test whether Wnt/β-catenin signaling is activated in response to Oct4 knockdown, we conducted reporter assay using the TOPFLASH plasmid, which consists of a luciferase gene under the control of lymphocyte enhancer factor (LEF)/T-cell factor (TCF)-response elements [36]. Knockdown of Oct4 resulted in the activation of TOPFLASH signal in 24 h after transfection (Fig. 3B). This activation was abolished when β-catenin was concomitantly knocked down, which confirms that the activation of TOPFLASH signal was mediated by Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Fig. 3B). Even when Wnt/β-catenin signaling was elevated by a constitutively active receptor construct Lrp5ΔN [23,37], TOPFLASH signal was further intensified by concomitant Oct4 knockdown (Fig. 3C). This suggests that Wnt/β-catenin signaling is attenuated by Oct4 in P19 EC cells.

Oct4 inhibits Wnt/β-catenin signaling through its transcriptional activator function

We further conducted gain-of-function experiments to examine the negative effects of Oct4 on Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Overexpression of Oct4 diminished in a dose-dependent manner the TOPFLASH signal that was activated by Lrp5ΔN (Fig. 3D). In contrast, the signal of control FOPFLASH, which contains mutations in the LEF/TCF-response elements, was not significantly reduced by overexpression of Oct4, indicating that the effect of Oct4 on TOPFLASH was due to inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Fig. 3E). Further, overexpression of Oct4 inhibited TOPFLASH signal in human HEK293 cells (Fig. 3F), indicating that Oct4 can also interfere with Wnt/β-catenin signaling in a nonpluripotent cell line.

Because Wnt/β-catenin signaling is essential for mesoderm induction in normal development [38], we examined whether the overexpression of Oct4 interferes with the formation of mesoderm in P19 EC cells. The induction of P19 EC cells to give rise to skeletal and cardiac muscle cells can be initiated by culturing as cell aggregates in the presence of 1% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) [39,40]. With this method, various mesoderm-specific genes, such as Snai1 and Fgf8, are upregulated during 3 days of aggregation culture [20]. We transiently transfected P19 EC cells with the Oct4-expression plasmid or the control GFP-expression plasmid, and analyzed gene expression patterns after culturing as aggregates for 3 days in the medium containing 1% DMSO. The expression levels of many genes that are normally involved in mesoderm development, such as Snai1, Fgf8, Wnt3a, Cdx2, Hoxb1, Lhx1, and Tbx6, were diminished in cell aggregates that overexpressed Oct4, whereas a pluripotency regulator Foxd3 was upregulated (Fig. 3G). In contrast, the expression levels of housekeeping genes, EF1α and β-actin, were not different between Oct4-expressing and control aggregates (Fig. 3G). This result suggests that Oct4 overexpression compromises the mesoderm development in P19 EC cells.

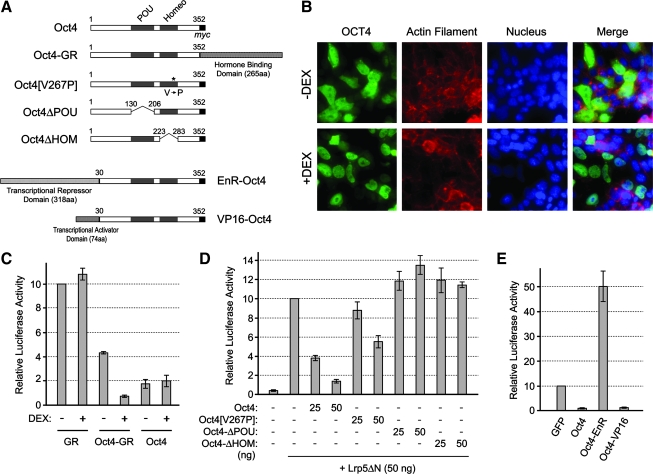

To gain insight into the mechanism of Oct4-mediated inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, we conducted the following 3 types of experiments. First, we examined whether nuclear localization of Oct4 is required for its inhibitory effect on Wnt/β-catenin signaling. By adopting the same strategy that has been employed for various transcription factors [41–43], we generated a chimeric construct, in which Oct4 was fused with the ligand-binding domain of GR (Fig. 4A). In this strategy, a GR-fused transcription factor is sequestered in the cytoplasm in the absence of a ligand, whereas the addition of ligand, such as dexamethasone (DEX), liberates the fusion protein, which can translocate into the nucleus to exert its transcriptional regulatory functions. Consistent with this scheme, overexpressed Oct4-GR distributed throughout in P19 EC cells in the absence of DEX, whereas it was mostly confined in the nucleus in the presence of DEX (Fig. 4B). In the absence of DEX, Oct4-GR only mildly inhibited TOPFLASH signal as compared with normal Oct4 (Fig. 4C). However, DEX treatment enhanced the ability of Oct4-GR to inhibit TOPFLASH signal. In contrast, DEX did not alter the effect of normal Oct4 or GR on TOPFLASH (Fig. 4C). This suggests that nuclear localization of Oct4 is critical for its inhibitory effect on Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

FIG. 4.

Nuclear function of Oct4 is critical for suppression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. (A) Structures of various modified Oct4 constructs. (B) Distribution of Oct4-GR fusion protein in response to DEX treatment (1 μM). The fusion protein is detected immunocytochemically using anti-Oct4 antibody. Actin filament and nucleus are observed with Alexa 546-phalloidin and DAPI, respectively. (C) Effective inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by Oct4-GR in the presence of DEX. (D) Effects of Oct4 deletion and mutation constructs on Wnt/β-catenin signaling. (E) Effects of EnR-Oct4 and VP16-Oct4 on Wnt/β-catenin signaling. In (B-E), cells are fixed for immunostaining or lysed for luciferase assay 1 day after plasmid transfection. DEX, dexamethasone; GR, glucocorticoid receptor. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd.

Second, we investigated whether the DNA-binding domains of Oct4 are required to inhibit Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Deletion of POU or homeodomain abolished the ability of Oct4 to suppress TOPFLASH signal (Fig. 4D). Also, a point mutation (V267P) in the homeodomain, which has been shown to impair the ability of Oct4 to maintain pluripotency in ES cells [44], diminished the inhibitory effect on TOPFLASH signal (Fig. 4D). This suggests that the DNA-binding ability of Oct4 is essential for its inhibitory effect on Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Third, we examined whether Oct4 acts as a transcriptional activator or transcriptional repressor to exert its negative effect on Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Chimeric constructs were generated, in which the N-terminus of Oct4 was fused with the transcriptional activation domain of the herpes simplex virus VP16 [45,46] or with the transcriptional repression domain of Drosophila Engrailed (EnR) [47–49] (Fig. 4A). VP16-Oct4 diminished TOPFLASH signal as effectively as normal Oct4. In contrast, EnR-Oct4 increased TOPFLASH signal (Fig. 4E), which is similar to the situation in the Oct4 knockdown. Therefore, the action of Oct4 as a transcriptional activator is critical for the inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, raising the possibility that Oct4 activates the transcription of its target genes, which in turn interfere with Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

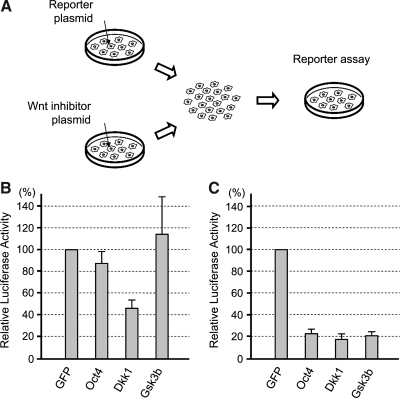

Various molecules have been identified that negatively regulate Wnt/β-catenin signaling [50]. Some negative regulators act in a cell-autonomous manner by inhibiting intracellular signal transduction, whereas others act at the extracellular level by interfering with ligand–receptor interactions. To gain insight into the nature of the inhibitory factors that are transcriptionally activated by Oct4, we examined whether the Oct4 overexpression interferes with Wnt/β-catenin signaling in a cell-autonomous or non-cell-autonomous manner. One group of P19 EC cells was transfected with TOPFLASH reporter plasmid, and another group was transfected with the plasmid encoding an inhibitor of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, namely, Dkk1 (as an example of non-cell-autonomous inhibitors), Gsk3b (as an example of cell-autonomous inhibitors), and Oct4 (Fig. 5A). The 2 groups of cells were mixed together 6 h after transfection, cocultured for another 18 h, and assayed for the TOPFLASH activity. TOPFLASH signal was distinctly reduced when cocultured with Dkk1-expressing cells but not with control (GFP-expressing) cells (Fig. 5B), consistent with Dkk1 being a non-cell-autonomous inhibitor. In contrast, the coculture with Gsk3b-expressing or Oct4-expressing cells did not diminish TOPFLASH signal (Fig. 5B). It is possible, however, that Oct4 may be a less potent inhibitor of Wnt/β-catenin signaling than Dkk1, which could contribute to the lack of TOPFLASH inhibition by Oct4-expressing cells in this experiment. To test this possibility, we conducted cotransfection experiment, in which both TOPFLASH and an inhibitor plasmid were transfected in the same group of cells, and compared their potencies of Wnt/β-catenin signaling inhibition. In the cotransfection experiment, Oct4 was as potent as Dkk1 and Gsk3b in inhibiting TOPFLASH activity (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that Oct4-induced factors are likely to act cell-autonomously to inhibit Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

FIG. 5.

Cell-autonomous inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by Oct4. (A) A diagram depicting the cell-mixing experiment. First, one group of P19 EC cells is transfected with reporter plasmids (TOPFLASH and pRL-TK) and the other group is transfected with plasmid encoding GFP or Wnt inhibitor (Oct4, Gsk3b, or Dkk1). Six hours after transfection, cells are detached from culture dishes, washed, and then mixed together for 18 h of culture, followed by luciferase assay. (B) Reporter assay data of the cell-mixing experiments, showing the reduction in Wnt/β-catenin signaling only when mixed with Dkk1-expressing cells. (C) Reporter assay data of the cotransfection experiment. P19 EC cells are cotransfected with reporter plasmids and Wnt inhibitor plasmid. Cells are lysed for luciferase assay 1 day after transfection. All 3 inhibitor plasmids are equally effective in suppressing Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

To gain insight into the identity of cell-autonomous inhibitors that are downstream of Oct4, we examined the transcriptional profile of Oct4-knockdown cells. P19 EC cells were transfected with the Oct4-specific shRNA plasmid or with nontarget shRNA plasmid, and RNA were extracted after 48 h for microarray analysis. The expression levels for known cell-autonomous inhibitors of Wnt/β-catenin signaling were compared between the 2 groups (Table 1 and Supplementary Data). Three Groucho homologs, Tle1, Tle3, and Tle6, were mildly decreased in Oct4-knockdown cells. However, the extent of reduction of these genes was not >2-fold, raising the possibility that they are not sole transcriptional targets of Oct4 that are responsible for the negative regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

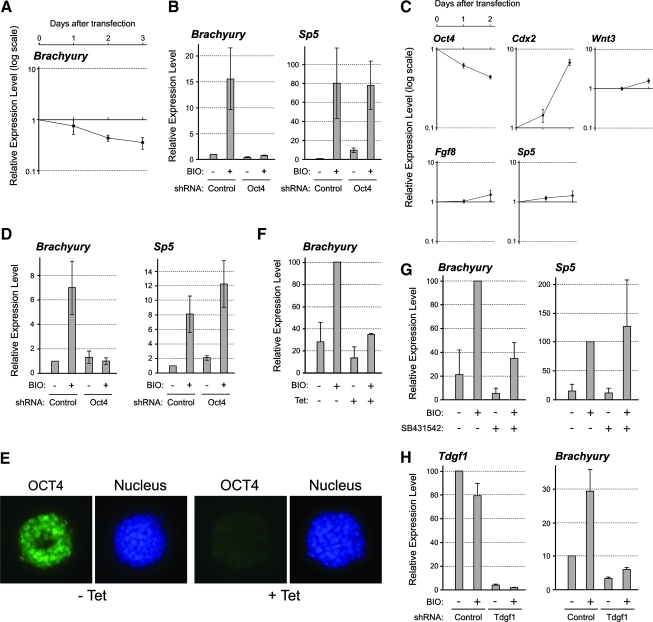

Oct4 is essential for the activation of Brachyury in response to Wnt/β-catenin signaling

Despite that Oct4 knockdown in P19 EC cells resulted in the activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, we found that it did not upregulate the expression of Brachyury (Fig. 6A). Brachyury is a key regulator of mesoderm formation that is specifically expressed in the primitive streak, and is known to be a direct target of Wnt/β-catenin signaling [51,52]. The knockdown of Oct4 by the shRNA plasmid for up to 72 h did not elevate Brachyury expression, as demonstrated by qRT-PCR (Fig. 6A). This was in marked contrast to the distinct upregulation of other primitive streak-specific genes, such as Wnt3, Sp5, and Fgf8 (Fig. 2A). To test whether the lack of Brachyury upregulation was due to insufficient activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, we treated Oct4-knockdown cells with BIO ([2′Z,3′E]-6-bromoindirubin-3′-oxime), a potent inhibitor of Gsk3, to further activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Nonetheless, BIO treatment did not upregulate Brachyury in Oct4-knockdown cells (Fig. 6B). In contrast, BIO treatment further upregulated Sp5, indicating that Wnt/β-catenin signaling was strongly activated by BIO in Oct4-knockdown cells. This suggests that Oct4 is indispensable for Brachyury upregulation in P19 EC cells even when Wnt/β-catenin signaling is active.

FIG. 6.

Oct4 is essential for the induction of Brachyury expression by Wnt/β-catenin signaling. (A) The expression levels of Brachyury in the same Oct4-knockdown P19 EC cells that are used for the experiments shown in Figure 2A. (B) The induction of Brachyury and Sp5 by BIO (2 μM) in the presence or absence of Oct4 in P19 EC cells. P19 EC cells are transfected with control or Oct4 shRNA plasmid for 24 h, and then cultured in the presence of puromycin with or without BIO for another 24 h, followed by qRT-PCR analysis. (C) Gene expression changes in ES cells in response to Oct4 knockdown by shRNA plasmid transfection. The data show gene expression levels in Oct4 shRNA plasmid-transfected relative to control shRNA plasmid-transfected ES cells. After 1 day of transfection, ES cells are cultured for another day in the presence of puromycin to enrich for transfected cells. (D) The induction of Brachyury and Sp5 by BIO in the presence or absence of Oct4 in ES cells. The experiment is conducted in the same manner as the one presented in (B). (E) Reduction of Oct4 protein in ZHBTc4 ES cells in response to tetracycline (Tet; 10 ng/mL) treatment for 24 h. Oct4 protein is detected immunocytochemically and the nucleus is observed with DAPI. (F) The induction of Brachyury by BIO in ZHBTc4 ES cells. ZHBTc4 ES cells are cultured with or without BIO and/or Tet for 24 h, followed by qRT-PCR. (G) The induction of Brachyury and Sp5 by BIO in the presence or absence of Nodal signaling inhibitor SB431542. P19 EC cells are cultured with or without BIO and/or SB431542 (2 μM) for 24 h, followed by qRT-PCR. (H) The induction of Brachyury by BIO in the absence of Tdgf1. P19 cells are transfected with Tdgf1-specific shRNA plasmid, cultured with puromycin for 24 h, and then treated with BIO for 24 h, followed by qRT-PCR. ES, embryonic stem. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd.

Brachyury can also be upregulated by Wnt/β-catenin signaling in ES cells [52]. To test whether Brachyury upregulation is also dependent on Oct4 in ES cells, we knocked down Oct4 in ES cells and concomitantly activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling. We employed 2 methods to knockdown Oct4 expression in ES cells. One is transfection of the Oct4-specific shRNA plasmid. The extent of Oct4 knockdown was 38% and 56% at 24 and 48 h after transfection, respectively, which was milder as compared with the knockdown in P19 EC cells, possibly due to lower transfection efficiency (Fig. 6C). Regardless, significant upregulation of Cdx2 was observed (Fig. 6C), which is consistent with the previous finding that Oct4 negatively regulates the expression of Cdx2 in ES cells [10]. The upregulation of Wnt3, Sp5, and Fgf8 was not evident in Oct4-knockdown ES cells (Fig. 6C), which was in contrast to the situation in P19 EC cells. Consistent with the previous study [52], activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by BIO treatment robustly upregulated Brachyury and Sp5 in ES cells (Fig. 6D). However, when Oct4 expression was knocked down by shRNA, BIO treatment was unable to upregulate Brachyury expression effectively (Fig. 6D).

As another method to knockdown Oct4 in ES cells, we employed ZHBTc4 ES cells, in which Oct4 expression can be conditionally turned off by tetracycline treatment [9] (Fig. 6E). BIO treatment significantly activated Brachyury expression in ZHBTc4 ES cells (Fig. 6F). However, when cotreated with tetracycline, BIO treatment was unable to upregulate Brachyury effectively (Fig. 6F). Thus, the upregulation of Brachyury by Wnt/β-catenin signaling is dependent on Oct4 in both P19 EC and ES cells.

The activation of Brachyury by Wnt/β-catenin signaling is dependent on Nodal signaling

Because transcriptional targets of Oct4 may be involved in the responsiveness of Brachyury gene to Wnt/β-catenin signaling, we examined the microarray data (Supplementary Excel file) for genes that were downregulated by Oct4 knockdown. One of them was Tdgf1 (also known as Cripto), whose reduction in Oct4-knockdown cells was also confirmed by qRT-PCR analysis (24.1% ± 1.6% of control level; n = 3). Tdgf1 encodes a CFC family member of Nodal coreceptor, and is essential for activation of Nodal signaling [53]. Thus, we tested whether active Nodal signaling is essential for the activation of Brachyury expression in response to Wnt/β-catenin signaling. When P19 cells were cotreated with a Nodal inhibitor SB431542, BIO failed to upregulate Brachyury (Fig. 6G). However, Sp5 expression was strongly upregulated by BIO even in the presence of SB431542, indicating that the inhibitor did not interfere with Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Fig. 6G). Further, the knockdown of Tdgf1 expression using a specific shRNA plasmid also abrogated the upregulation of Brachyury in response to BIO treatment (Fig. 6H). This result suggests that active Nodal-Tdgf1 signaling confers the responsiveness of Brachyury to Wnt/β-catenin signaling in P19 EC cells.

Discussion

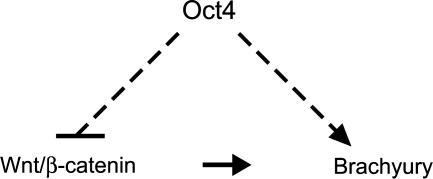

In this study, we investigated the role of Oct4 in the primitive ectoderm using P19 EC cells as an in vitro model. We found that Oct4, through its action as a transcriptional activator, suppresses Wnt/β-catenin signaling, a key inducer of mesoderm in the primitive ectoderm. At the same time, Oct4 is required for the upregulation of Brachyury, a critical transcription factor for mesoderm development, in response to Wnt/β-catenin signaling. We propose that this dual action of Oct4 serves as one of the fundamental mechanisms to establish pluripotency in the primitive ectoderm (Fig. 7). Maintenance of pluripotency requires 2 aspects of regulations: one is to prevent differentiation and the other is to retain competence for differentiation. Oct4 in P19 EC cells exerts these 2 types of regulations by antagonizing mesoderm-inducing signal (ie, suppression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling) and also by conferring competency for mesoderm gene expression (ie, responsiveness of Brachyury to Wnt/β-catenin signaling).

FIG. 7.

A model depicting how Oct4 maintains undifferentiated state in P19 EC cell. Oct4 interferes with Wnt/β-catenin signaling that is responsible for the initiation of mesoderm formation, while it acts as a competence factor for the induction of Brachyury gene in response to Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

We showed that overexpression of Oct4 suppresses Wnt/β-catenin signaling in P19 EC cells as well as in HEK293 cells. However, response of Wnt/β-catenin signaling to excessive Oct4 may vary depending on cell types. For example, ectopic expression of Oct4 in the adult mouse using the doxycycline-inducible system results in dysplastic growth of epithelial tissues accompanied by accumulation of β-catenin protein and activation of TCF-mediated transcription, suggesting that Oct4 overexpression activates, rather than inhibits, Wnt/β-catenin signaling [54]. In the present study, we showed that the inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by Oct4 is dependent on its action as a transcriptional activator. Because genes that are activated by Oct4 overexpression are likely to differ depending on cellular context, its effect on Wnt/β-catenin signaling may also depend on cell types accordingly.

Our present study indicates that the inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by Oct4 is mediated by the activation of its transcriptional targets, although their identity is currently unclear. Our microarray and qRT-PCR studies (Table 1) showed that several known Wnt/β-catenin signaling inhibitors, such as Apc2, Cby1, Tle1, Tle3, and Tle6, were modestly but distinctly downregulated when Oct4 was knocked down. However, we also observed that several other known inhibitors, such as Gsk3b, Axin1, Apc, Ctnnbip1, Tax1bp3, Tle2, and Aes, were upregulated, which appears to be contradictory to our observation that Wnt/β-catenin signaling is activated in response to Oct4 knockdown. Currently, we do not know how much impact down- or upregulation of each inhibitor would exert on Wnt/β-catenin signaling. One speculation is that those inhibitors that were downregulated may impact on Wnt/β-catenin signaling more strongly than those that were upregulated, which may have resulted in the overall activation of signaling.

Although the present study suggests that the inhibitory effect of Oct4 on Wnt/β-catenin signaling is indirect, Oct4 protein has been shown to physically bind to β-catenin protein in ES cells [55], raising the possibility that Oct4 may also exert direct influence on Wnt/β-catenin signaling. In ES cells, the activation of β-catenin promotes long-term proliferation of ES cells by upregulating pluripotency regulator Nanog, which is mediated by the interaction of β-catenin with Oct4 [55–59]. Whether the transcriptional activator function of β-catenin is modulated by the interaction with Oct4 is yet unknown. It is of particular interest to determine the mode of interaction between Oct4 and β-catenin, with respect to whether Oct4 competes with LEF/TCF for binding to β-catenin. Oct25, a Xenopus homolog of Oct4, has been shown to bind to Tcf3 in Xenopus embryos [60], raising the possibility that Oct4 may interfere with Wnt/β-catenin signaling through its interaction with LEF/TCF. For example, LEF/TCF that is bound by Oct4 may act constitutively as a transcriptional repressor even in the presence of β-catenin, whereas in the absence of Oct4, TCF/LEF acts as a transcriptional activator together with β-catenin.

An ∼1 kb-upstream region of Brachyury gene is sufficient to direct the primitive streak-specific expression of transgene [61]. This suggests that the 1 kb-upstream region contains cis-regulatory elements that are sufficient for Brachyury expression in the primitive streak in a temporally and spatially regulated manner. The 1 kb-upstream region also contains functional TCF-binding sites, indicating that it is responsible for the response to Wnt/β-catenin signaling [51,52]. To obtain insight into the mode of interactions between Oct4 protein and the Brachyury cis-regulatory elements, we examined in silico whether the 1 kb-upstream region contains Oct4-binding consensus sequence, ATGC(A/T)AAT [62,63]. However, no Oct4-binding sequence was found in the 1 kb-upstream region. Further, neither the 10 kb-upstream sequence nor the first and second introns of the Brachyury gene contains an Oct4-binding consensus sequence. Thus, it is unlikely that Oct4 protein directly binds to the Brachyury promoter to regulate its responsiveness to Wnt/β-catenin signaling. This notion is consistent with our data in Fig. 6H, which showed that Oct4 regulates the expression of Tdgf1, which in turn controls the responsiveness of the Brachyury gene to Wnt/β-catenin signaling. These results suggest that the action of Oct4 on the Brachyury gene is indirect, although we cannot exclude the possibility that distantly located cis-regulatory elements may interact with Oct4 protein directly and influence the expression of Brachyury gene.

Previous studies have shown that the Brachyury transcriptional promoter contains LEF/TCF binding sites, which indicates that Brachyury is a direct transcriptional target of Wnt/β-catenin signaling [51,52]. Nonetheless, as shown in the present study, Wnt/β-catenin signaling cannot induce Brachyury expression in the absence of Oct4 in P19 EC cells. The dependence of Brachyury expression on Oct4 has also been demonstrated in ES cells [64,65], which we also confirmed in the present study. A potential mechanism by which Oct4 regulates the responsiveness of Brachyury gene to Wnt/β-catenin signaling is the transcriptional activation of Nodal coreceptor Tdgf1. Nodal signaling plays essential roles in mesoderm formation in normal embryos, such that either Nodal-knockout or Tdgf1-knockout embryo is unable to form the primitive streak [66,67]. It is likely that Nodal signaling works together with Wnt/β-catenin signaling to achieve robust expression of Brachyury in the primitive streak. Oct4 in the primitive ectoderm may act as a critical regulator that balances the 2 signaling pathways to maintain pluripotency: on one hand, it inhibits Wnt/β-catenin signaling; on the other hand, it confers competency for Nodal signal transduction through the expression of Tdgf1.

In the present study, we used P19 EC cells as an in vitro model to study the roles of Oct4 in the primitive ectoderm. In future studies, however, it is critical to examine whether Oct4 exhibits the same characteristics in vivo as those that we observed in P19 EC cells. An experimental approach to address this is to remove Oct4 activity specifically in the primitive ectoderm but not in the ICM. This may be achieved by conditional knockout of the Oct4 gene using a primitive ectoderm-specific Cre recombinase transgene. Alternatively, targeted mutation of the PE may be more ideal to assess the primitive ectoderm-specific roles of Oct4, because PE functions to activate the Oct4 expression in the primitive ectoderm but not in ICM or PGC [5].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. H. Niwa for ZHBTc4 cells and pCAG-IP-HA267V/P plasmid, and Dr. R. Allsopp for mouse ES cells. The authors thank Ms. Lina Miyakawa, who participated in the early stage of this project. This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (NIH) Hawaii State Biomedical Research Infrastructural Network (P20RR16467), the Research Centers in Minority Institutions program of the National Center for Research Resources (G12RR003061), and the George F. Straub Trust Fund of the Hawaii Community Foundation Medical Research Grant (20060374) to Y.M., and the NIH Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence (P20RR024206) to V.B.A.

Author Disclosure Statement

There are no conflicts of interest relating to this work for any of the authors.

References

- 1.Okamoto K. Okazawa H. Okuda A. Sakai M. Muramatsu M. Hamada H. A novel octamer binding transcription factor is differentially expressed in mouse embryonic cells. Cell. 1990;60:461–472. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90597-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosner MH. Vigano MA. Ozato K. Timmons PM. Poirier F. Rigby PW. Staudt LM. A POU-domain transcription factor in early stem cells and germ cells of the mammalian embryo. Nature. 1990;345:686–692. doi: 10.1038/345686a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scholer HR. Ruppert S. Suzuki N. Chowdhury K. Gruss P. New type of POU domain in germ line-specific protein Oct-4. Nature. 1990;344:435–439. doi: 10.1038/344435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pesce M. Scholer HR. Oct-4: control of totipotency and germline determination. Mol Reprod Dev. 2000;55:452–457. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(200004)55:4<452::AID-MRD14>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeom YI. Fuhrmann G. Ovitt CE. Brehm A. Ohbo K. Gross M. Hubner K. Scholer HR. Germline regulatory element of Oct-4 specific for the totipotent cycle of embryonal cells. Development. 1996;122:881–894. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.3.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brons IG. Smithers LE. Trotter MW. Rugg-Gunn P. Sun B. Chuva de Sousa Lopes SM. Howlett SK. Clarkson A. Ahrlund-Richter L. Pedersen RA. Vallier L. Derivation of pluripotent epiblast stem cells from mammalian embryos. Nature. 2007;448:191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature05950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tesar PJ. Chenoweth JG. Brook FA. Davies TJ. Evans EP. Mack DL. Gardner RL. McKay RD. New cell lines from mouse epiblast share defining features with human embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2007;448:196–199. doi: 10.1038/nature05972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nichols J. Zevnik B. Anastassiadis K. Niwa H. Klewe-Nebenius D. Chambers I. Scholer H. Smith A. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell. 1998;95:379–391. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niwa H. Miyazaki J. Smith AG. Quantitative expression of Oct-3/4 defines differentiation, dedifferentiation or self-renewal of ES cells. Nat Genet. 2000;24:372–376. doi: 10.1038/74199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niwa H. Toyooka Y. Shimosato D. Strumpf D. Takahashi K. Yagi R. Rossant J. Interaction between Oct3/4 and Cdx2 determines trophectoderm differentiation. Cell. 2005;123:917–929. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strumpf D. Mao CA. Yamanaka Y. Ralston A. Chawengsaksophak K. Beck F. Rossant J. Cdx2 is required for correct cell fate specification and differentiation of trophectoderm in the mouse blastocyst. Development. 2005;132:2093–2102. doi: 10.1242/dev.01801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyer LA. Lee TI. Cole MF. Johnstone SE. Levine SS. Zucker JP. Guenther MG. Kumar RM. Murray HL. Jenner RG. Gifford DK. Melton DA. Jaenisch R. Young RA. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2005;122:947–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loh YH. Wu Q. Chew JL. Vega VB. Zhang W. Chen X. Bourque G. George J. Leong B. Liu J. Wong KY. Sung KW. Lee CW. Zhao XD. Chiu KP. Lipovich L. Kuznetsov VA. Robson P. Stanton LW. Wei CL. Ruan Y. Lim B. Ng HH. The Oct4 and Nanog transcription network regulates pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Genet. 2006;38:431–440. doi: 10.1038/ng1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharov AA. Masui S. Sharova LV. Piao Y. Aiba K. Matoba R. Xin L. Niwa H. Ko MS. Identification of Pou5f1, Sox2, and Nanog downstream target genes with statistical confidence by applying a novel algorithm to time course microarray and genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation data. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:269. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi K. Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kehler J. Tolkunova E. Koschorz B. Pesce M. Gentile L. Boiani M. Lomeli H. Nagy A. McLaughlin KJ. Scholer HR. Tomilin A. Oct4 is required for primordial germ cell survival. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:1078–1083. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okamura D. Tokitake Y. Niwa H. Matsui Y. Requirement of Oct3/4 function for germ cell specification. Dev Biol. 2008;317:576–584. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones-Villeneuve EM. McBurney MW. Rogers KA. Kalnins VI. Retinoic acid induces embryonal carcinoma cells to differentiate into neurons and glial cells. J Cell Biol. 1982;94:253–262. doi: 10.1083/jcb.94.2.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niwa H. How is pluripotency determined and maintained? Development. 2007;134:635–646. doi: 10.1242/dev.02787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marikawa Y. Tamashiro DA. Fujita TC. Alarcon VB. Aggregated P19 mouse embryonal carcinoma cells as a simple in vitro model to study the molecular regulations of mesoderm formation and axial elongation morphogenesis. Genesis. 2009;47:93–106. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu P. Wakamiya M. Shea MJ. Albrecht U. Behringer RR. Bradley A. Requirement for Wnt3 in vertebrate axis formation. Nat Genet. 1999;22:361–365. doi: 10.1038/11932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huelsken J. Vogel R. Brinkmann V. Erdmann B. Birchmeier C. Birchmeier W. Requirement for beta-catenin in anterior-posterior axis formation in mice. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:567–578. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.3.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tamashiro DA. Alarcon VB. Marikawa Y. Ectopic expression of mouse Sry interferes with Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mouse embryonal carcinoma cell lines. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2008;1780:1395–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy CL. Polak JM. Differentiating embryonic stem cells: GAPDH, but neither HPRT nor beta-tubulin is suitable as an internal standard for measuring RNA levels. Tissue Eng. 2002;8:551–559. doi: 10.1089/107632702760240472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ying QL. Nichols J. Chambers I. Smith A. BMP induction of Id proteins suppresses differentiation and sustains embryonic stem cell self-renewal in collaboration with STAT3. Cell. 2003;115:281–292. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00847-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ben-Haim N. Lu C. Guzman-Ayala M. Pescatore L. Mesnard D. Bischofberger M. Naef F. Robertson EJ. Constam DB. The nodal precursor acting via activin receptors induces mesoderm by maintaining a source of its convertases and BMP4. Dev Cell. 2006;11:313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimmerman LB. De Jesus-Escobar JM. Harland RM. The Spemann organizer signal noggin binds and inactivates bone morphogenetic protein 4. Cell. 1996;86:599–606. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawano Y. Kypta R. Secreted antagonists of the Wnt signalling pathway. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2627–2634. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuan H. Corbi N. Basilico C. Dailey L. Developmental-specific activity of the FGF-4 enhancer requires the synergistic action of Sox2 and Oct-3. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2635–2645. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.21.2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodda DJ. Chew JL. Lim LH. Loh YH. Wang B. Ng HH. Robson P. Transcriptional regulation of nanog by OCT4 and SOX2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24731–24737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanna LA. Foreman RK. Tarasenko IA. Kessler DS. Labosky PA. Requirement for Foxd3 in maintaining pluripotent cells of the early mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2650–2661. doi: 10.1101/gad.1020502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrison SM. Houzelstein D. Dunwoodie SL. Beddington RS. Sp5, a new member of the Sp1 family, is dynamically expressed during development and genetically interacts with Brachyury. Dev Biol. 2000;227:358–372. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crossley PH. Martin GR. The mouse Fgf8 gene encodes a family of polypeptides and is expressed in regions that direct outgrowth and patterning in the developing embryo. Development. 1995;121:439–451. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beck F. Erler T. Russell A. James R. Expression of Cdx-2 in the mouse embryo and placenta: possible role in patterning of the extra-embryonic membranes. Dev Dyn. 1995;204:219–227. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002040302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ciruna BG. Rossant J. Expression of the T-box gene Eomesodermin during early mouse development. Mech Dev. 1999;81:199–203. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korinek V. Barker N. Morin PJ. van Wichen D. de Weger R. Kinzler KW. Vogelstein B. Clevers H. Constitutive transcriptional activation by a beta-catenin-Tcf complex in APC-/- colon carcinoma. Science. 1997;275:1784–1787. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamai K. Semenov M. Kato Y. Spokony R. Liu C. Katsuyama Y. Hess F. Saint-Jeannet JP. He X. LDL-receptor-related proteins in Wnt signal transduction. Nature. 2000;407:530–535. doi: 10.1038/35035117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marikawa Y. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and body plan formation in mouse embryos. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2006;17:175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ridgeway AG. Petropoulos H. Wilton S. Skerjanc IS. Wnt signaling regulates the function of MyoD and myogenin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32398–32405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gianakopoulos PJ. Skerjanc IS. Hedgehog signaling induces cardiomyogenesis in P19 Cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;180:21022–21028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502977200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hollenberg SM. Cheng PF. Weintraub H. Use of a conditional MyoD transcription factor in studies of MyoD trans-activation and muscle determination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8028–8032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kolm PJ. Sive HL. Efficient hormone-inducible protein function in Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol. 1995;171:267–272. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brocard J. Feil R. Chambon P. Metzger D. A chimeric Cre recombinase inducible by synthetic, but not by natural ligands of the glucocorticoid receptor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:4086–4090. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.17.4086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niwa H. Masui S. Chambers I. Smith AG. Miyazaki J. Phenotypic complementation establishes requirements for specific POU domain and generic transactivation function of Oct-3/4 in embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1526–1536. doi: 10.1128/mcb.22.5.1526-1536.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sadowski I. Ma J. Triezenberg S. Ptashne M. GAL4-VP16 is an unusually potent transcriptional activator. Nature. 1988;335:563–564. doi: 10.1038/335563a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Triezenberg SJ. Kingsbury RC. McKnight SL. Functional dissection of VP16, the trans-activator of herpes simplex virus immediate early gene expression. Genes Dev. 1988;2:718–729. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.6.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jaynes JB. O'Farrell PH. Active repression of transcription by the engrailed homeodomain protein. EMBO J. 1991;10:1427–1433. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han K. Manley JL. Functional domains of the Drosophila Engrailed protein. EMBO J. 1993;12:2723–2733. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05934.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Badiani P. Corbella P. Kioussis D. Marvel J. Weston K. Dominant interfering alleles define a role for c-Myb in T-cell development. Genes Dev. 1994;8:770–782. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.7.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Amerongen R. Nusse R. Towards an integrated view of Wnt signaling in development. Development. 2009;136:3205–3214. doi: 10.1242/dev.033910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamaguchi TP. Takada S. Yoshikawa Y. Wu N. McMahon AP. T (Brachyury) is a direct target of Wnt3a during paraxial mesoderm specification. Genes Dev. 1999;13:3185–3190. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.24.3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arnold SJ. Stappert J. Bauer A. Kispert A. Herrmann BG. Kemler R. Brachyury is a target gene of the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Mech Dev. 2000;91:249–258. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00309-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strizzi L. Bianco C. Normanno N. Salomon D. Cripto-1: a multifunctional modulator during embryogenesis and oncogenesis. Oncogene. 2005;24:5731–5741. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hochedlinger K. Yamada Y. Beard C. Jaenisch R. Ectopic expression of Oct-4 blocks progenitor-cell differentiation and causes dysplasia in epithelial tissues. Cell. 2005;121:465–477. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takao Y. Yokota T. Koide H. Beta-catenin up-regulates Nanog expression through interaction with Oct-3/4 in embryonic stem cell. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353:699–705. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sato N. Meijer L. Skaltsounis L. Greengard P. Brivanlou AH. Maintenance of pluripotency in human and mouse embryonic stem cells through activation of Wnt signaling by a pharmacological GSK-3-specific inhibitor. Nat Med. 2004;10:55–63. doi: 10.1038/nm979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hao J. Li TG. Qi X. Zhao DF. Zhao GQ. WNT/beta-catenin pathway up-regulates Stat3 and converges on LIF to prevent differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Dev Biol. 2006;290:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ogawa K. Nishinakamura R. Iwamatsu Y. Shimosato D. Niwa H. Synergistic action of Wnt and LIF in maintaining pluripotency of mouse ES cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singla DK. Schneider DJ. LeWinter MM. Sobel BE. wnt3a but not wnt11 supports self-renewal of embryonic stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;345:789–795. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cao Y. Siegel D. Donow C. Knochel S. Yuan L. Knoche E. POU-V factors antagonize maternal VegT activity and b-Catenin signaling in Xenopus embryos. EMBO J. 2007;26:2942–2954. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamaguchi H. Niimi T. Kitagawa Y. Miki K. Brachyury (T) expression in embryonal carcinoma P19 cells resembles its expression in primitive streak and tail-bud but not that in notochord. Dev Growth Differ. 1999;41:253–264. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.1999.413427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pesce M. Scholer HR. Oct-4: gatekeeper in the beginnings of mammalian development. Stem Cells. 2001;19:271–278. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.19-4-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jin VX. O'Geen H. Iyengar S. Green R. Farnham PJ. Identification of an OCT4 and SRY regulatory module using integrated computational and experimental genomics approaches. Genome Res. 2007;17:807–817. doi: 10.1101/gr.6006107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morrison GM. Brickman JM. Conserved roles of Oct4 homologues in maintaining multipotency during early vertebrate development. Development. 2006;133:2011–2022. doi: 10.1242/dev.02362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kong KY. Williamson EA. Rogers JH. Tran T. Hromas R. Dahl R. Expression of Scl in mesoderm rescues hematopoiesis in the absence of Oct-4. Blood. 2009;114:60–63. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-174755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ding J. Yang L. Yan YT. Chen A. Desai N. Wynshaw-Boris A. Shen MM. Cripto is required for correct orientation of the anterior-posterior axis in the mouse embryo. Nature. 1998;395:702–707. doi: 10.1038/27215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brennan J. Lu CC. Norris DP. Rodriguez TA. Beddington RS. Robertson EJ. Nodal signalling in the epiblast patterns the early mouse embryo. Nature. 2001;411:965–969. doi: 10.1038/35082103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu D. Pan W. GSK3: a multifaceted kinase in Wnt signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kikuchi A. Roles of axin in the Wnt signalling pathway. Cell Signal. 1999;11:777–788. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(99)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aoki K. Taketo MM. Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC): a multi-functional tumor suppressor gene. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3327–3335. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Maniatis T. A ubiquitin ligase complex essential for the NF-kappaB, Wnt/Wingless, and Hedgehog signaling pathways. Genes Dev. 1999;13:505–510. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.5.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tago K. Nakamura T. Nishita M. Hyodo J. Nagai S. Murata Y. Adachi S. Ohwada S. Morishita Y. Shibuya H. Akiyama T. Inhibition of Wnt signaling by ICAT, a novel beta-catenin-interacting protein. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1741–1749. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Takemaru K. Yamaguchi S. Lee YS. Zhang Y. Carthew RW. Moon RT. Chibby, a nuclear beta-catenin-associated antagonist of the Wnt/Wingless pathway. Nature. 2003;422:905–909. doi: 10.1038/nature01570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kanamori M. Sandy P. Marzinotto S. Benetti R. Kai C. Hayashizaki Y. Schneider C. Suzuki H. The PDZ protein tax-interacting protein-1 inhibits beta-catenin transcriptional activity and growth of colorectal cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38758–38764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jennings BH. Ish-Horowicz D. The Groucho/TLE/Grg family of transcriptional co-repressors. Genome Biol. 2008;9:205. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.