Abstract

We have investigated possible collinearity between the genomes of rice and Arabidopsis by comparing 126 annotated and mapped rice BAC sequences (∼20 Mb of sequence) with the annotated and complete Arabidopsis genome (∼115 Mb). Although we were able to identify several regions in which gene order is preserved, they are relatively small, and are interrupted by noncollinear genes. Computer simulation showed that these microscale collinearities are above the expectation for a random process. On the other hand, the order of exons within homologous genes (<2.5 kb) was preserved, as expected.

Comparative genomics can be used to gain knowledge of gene organization, and is particularly helpful in examining genome evolution (Keller and Geuillet 2000). Closely related species have extensive regions of gene collinearity, a phenomenon also known as synteny (Passarge et al. 1999), but as the evolutionary distance between two species increases, the segments of collinearity get shorter. The recent availability of the complete genomes of several model systems has sparked renewed interest in the study of collinearity because of the phenomenon's potential for transferring useful information from well-studied small genomes to larger ones (Rubin et al. 2000).

Arabidopsis thaliana, a member of the mustard family whose genome was completed in 2000, is a popular model system for dicots. Several studies have shown genome collinearity between Arabidopsis and closely related dicots. Acarkan et al. (2000) identified a collinear segment spanning >10 cM (∼10 Mb) between Arabidopsis and Capsella rubella. Over a 60-kb region, gene order and orientation were completely conserved. A syntenic segment for a 30-kb region on Arabidopsis Chromosome 4 was found to contain six genes also found in the same order in Brassica (Sadowski and Quiros 1998). Large segment duplications were identified in the Arabidopsis genome sequence, comprising 65.6 Mb or 58% of the genome (The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative 2000; Vision et al. 2000). A 105-kb tomato BAC clone shows conservation of gene content and order with four different segments of Arabidopsis chromosomes (Ku et al. 2000).

Rice (Oryza sativa), a model system for grasses, has also shown collinearity with other monocots. In a 1.9-cM region of rice, five genes show interrupted collinearity with maize Chromosome 4 (Tarchini et al. 2000). Moreover, three genes in the ∼20-kb Sh2–A1 region show complete collinearity with sorghum (Chen et al. 1997).

Arabidopsis and rice are expected to have great value as models for dicot and monocot genomic studies, respectively (Gale and Devos 1998). Comparative analysis of these two species will not only help in understanding the genomic similarities across the dicot/monocot divide, but also answer the practical question of whether we can use Arabidopsis as a reference to understand and annotate the rice genome (Bevan and Murphy 1999).

Previous studies have investigated collinearity between rice and Arabidopsis at both the genetic and physical map levels. In one study (Dodeweerd et al. 1999), rice EST clones totaling ∼200–300 kb homologous to Arabidopsis genomic DNA sequence were examined across a 194-kb region in Arabidopsis. Out of 24 homologous pairs in this region, 5 have conserved order, with the exception of a single inversion. However, a similar study across a 3-cM region of Arabidopsis Chromosome 1 did not identify conservation of gene order in rice (Devos et al. 1999). The scarcity of rice genomic sequence and the incomplete nature of the database of rice ESTs hampered both these studies.

In this study, we look at the nature and extent of Arabidopsis/rice collinearity by systematically analyzing 126 annotated rice bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) genomic sequences at increasingly fine scales.

RESULTS

We adopted the strategy of identifying rice and Arabidopsis homologs at the protein level and examining the collinearity of the homologous pairs across several length scales, starting at BAC lengths (∼150 kb), going down to sub-BAC level. This avoids artifacts arising from repetitive regions, which are heavily distributed in both rice and Arabidopsis genomes, and allows us to identify homologs that have diverged at the nucleotide level.

Our data sets for this study consist of all the annotated rice BAC genomic sequences available in the Rice Genome Project (RGP) database as of July 2001, and the set of Arabidopsis proteins (predicted and observed), retrieved from the MIPS Arabidopsis thaliana database (MATDB; http://www.mips.biochem.mpg.de/proj/thal/db/). As described in Methods, we removed overlapping segments from the rice BACs, yielding a rice data set of 126 BACs with a total length of about 20 Mb and 3011 annotated genes. Of the rice BACs in this data set, 108 are from Chromosome 1. The corresponding Arabidopsis protein data set consisted of 24,570 annotated proteins derived from 1567 Arabidopsis BACs.

Chromosome Distribution of Arabidopsis Homologs for Genes on Rice BACs

We first studied the chromosome distribution of rice/Arabidopsis homologs to determine whether rice and Arabidopsis share collinear segments on approximately the same scale as individual BACs (100–170 kb). For each of the annotated proteins on the 126 rice BACs, we performed BLASTP (Altschul et al. 1990) against the Arabidopsis protein data set, and declared a provisional homologous pair if the P value of the match was ≤10−5. This threshold was chosen with the knowledge that it would detect both orthologs and some paralogs, and would, if anything, overestimate the incidence of collinearity. Because the Arabidopsis genome is highly duplicated, some homologs may fall into duplicated blocks. To avoid missing syntenic segments because the high-scoring Arabidopsis homolog was involved in a segmental duplication, we downloaded the duplicated region of the Arabidopsis genome from the MIPS redundancy viewer (http://www.mips.biochem.mpg.de/proj/thal/db/gv/rv/rv_frame.html) and incorporated that information into our analysis. We adopted the rule that if the homolog hit falls into a duplicated block on different chromosomes or a different region on the same chromosome, homologs on the lower-numbered chromosome or earlier-region chromosome were chosen. This procedure effectively collapses duplicated regions into a single region in an unbiased fashion, and maximizes the opportunity to detect synteny. We then used the Arabidopsis physical map to relate the positions of putative rice/Arabidopsis homologs to the Arabidopsis chromosomes on which they were found.

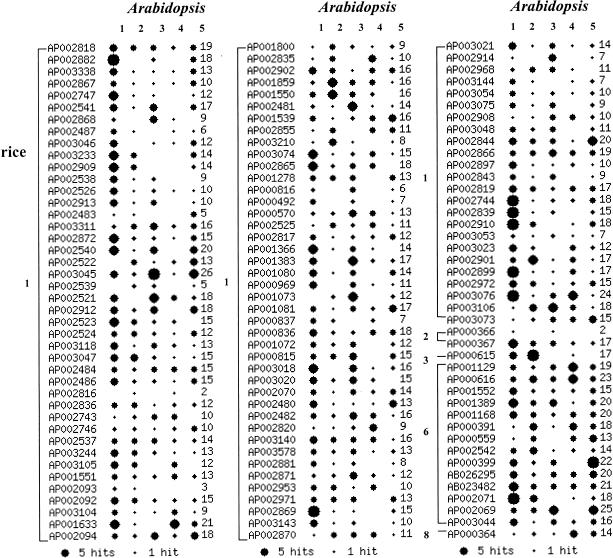

For the 126 rice BACs analyzed, putative homologs were found on 728 Arabidopsis BACs. Of the 3011 annotated rice proteins, 58% (1747) had homologs on Arabidopsis, of which 26% (456) were involved in segmental duplications of the Arabidopsis genome. Following our rule, 191 homologs were reassigned to lower-numbered chromosomes and 38 homologs were reassigned to a lower region of the same chromosome. Figure 1 shows the distribution of these homolog pairs on the Arabidopsis genome. Each row represents an individual rice BAC. The number of homologs found on various chromosomes of Arabidopsis are represented by the size of the star. The number after the star on each row is the total number of Arabidopsis protein homologs on the rice BAC. The striking observation is that at the BAC size scale, there is no obvious bias of rice BACs for particular Arabidopsis chromosomes. In all but three cases, the proteins annotated on rice BACs are distributed evenly across three or more chromosomes. The three exceptions are rice BACs that have homologous proteins represented on two Arabidopsis chromosomes. These BACs are very short and contain just 2–3 Arabidopsis homologs. No rice BAC in the entire data set had its protein homologs confined to a single Arabidopsis chromosome.

Figure 1.

Clustering of predicted proteins on rice BACs to homologs on different chromosomes of Arabidopsis. Each row is for a rice BAC, and the size of starburst indicates the number of rice proteins on the BAC showing homology with Arabidopsis proteins on a specific chromosome. The number after the starburst is the total number of hits. Following are the number of putative proteins on each BAC. Because of removing overlapping genes on neighboring clones, some of those BACs contain fewer proteins; these are indicated in the following list by an asterisk. The actual number is indicated following the original one. On Chromosome 1: AP002818(25), AP002882(32), AP003338(17), *AP002867(25)(14), *AP002747(30)(18), AP002541(31), *AP002868(23)(21), AP002487(11), AP003046(24), AP003233(27), AP002909(21), AP002538(20), AP002526(27), AP002913(24), *AP002483(26)(9), AP003311(30), AP002872(32), AP002540(34), *AP002522(30)(15), AP003045(32), *AP002539(36)(9), AP002521(31), AP002912(29), AP002523(23), *AP002524(27)(17), AP003118(22), AP003047(23), *AP002484(25)(21), *AP002486(28)(25), *AP002816(24)(7), *AP002836(21)(18), *AP002743(26)(22), *AP002746(34)(21), AP002537(29), AP003244(19), AP003105(27), AP001551(31), *AP002093(27)(7), *AP002092(33)(32), *AP003104(32)(15), AP001633(36), AP002094(25), *AP001800(27)(13), *AP002835(21)(16), AP002902(27), AP001859(23), AP001550(26), *AP002481(26)(19), AP001539(29), *AP002855(23)(19), AP003210(21), AP003074(34), AP002865(28), *AP001278(30)(23), *AP000816(12)(10), *AP000492(33)(9), AP000570(33), *AP002525(25)(21), *AP002817(24)(15), *AP001366(27)(24), AP001383(27), *AP001080(25)(21), *AP000969(23)(17), *AP001073(29)(18), AP001081(31), *AP000837(18)(12), AP000836(24), AP001072(21), AP000815(25), AP003018(25), AP003020(26), AP002070(30), *AP002480(28)(26), AP002482(34), AP002820(12), AP003140(30), AP003578(20), AP002881(15), AP002871(27), AP002953(23), AP002971(25), AP002869(35), AP003143(20), AP002870(21), AP003021(31), AP002914(19), AP002968(21), AP003144(18), AP003054(16), AP003075(18), AP002908(24), AP003048(21), AP002844(27), AP002866(34), AP002897(21), AP002843(27), AP002819(25), AP002744(36), AP002839(32), AP002910(33), AP003053(14), AP003023(25), AP002901(33), AP002899(28), AP002972(22), AP003076(40), AP003106(29), AP003073(33). On Chromosome 2: AP000366(3), AP000367(20). On Chromosome 3: AP000615(28). On Chromosome 6: *AP001129(35)(28), AP000616(28), AP001552(25), AP001389(27), AP001168(27), *AP000391(27)(24), AP000559(28), AP002542(32), AP000399(32), AB026295(35), AB023482(32), AP002071(27), AP002069(29), AP003044(26). On Chromosome 8: AP000364(25).

If there were collinearities at the scale of a rice BAC, we would expect the homologs from a BAC to be concentrated on one or two Arabidopsis chromosomes. The fact that such clustering of homologs is not observed indicates that any collinear segments must be substantially smaller than a BAC.

Microcollinearity at the Sub-BAC Level

Because we were unable to detect collinearity at the BAC scale, we next asked whether detectable microcollinearity exists across shorter lengths. To do this, the same BLASTP search was performed for each rice gene against the Arabidopsis protein database. In this analysis, all hits with P values ≤10−5 were kept. We then performed an exhaustive search for collinear segments. The hits were organized in pairs (each pair consisting of an Arabidopsis protein and a homologous rice protein), and the pairs were grouped according to the Arabidopsis BACs on which they occurred. Within each group we then subgrouped and ordered the pairs according to the rice BACs on which they occurred. This allowed us to identify the collinear regions, as well as genes from one of the genomes that appeared to be duplicated several times on the other genome.

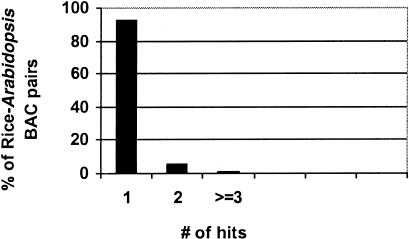

Figure 2 shows the results of this analysis. There are 5957 distinct Arabidopsis and rice BAC pairs that share at least one “hit,” where a hit is defined as a single distinct match between homologous proteins on rice and Arabidopsis BACs. To avoid complications arising from a single Arabidopsis protein with multiple rice homologs or vice versa, such cases were counted as a single hit only. In our analysis, there are 1103 Arabidopsis/rice BAC pairs that have a single Arabidopsis protein with multiple rice homologs, and 520 pairs that have a single rice protein with multiple Arabidopsis homologs. Of the total 5957 BAC pairs we analyzed, almost 93.3% (5555) of the BAC pairs are related by a single hit only; 330 of the BAC pairs (5.5%) are related by two hits, 72 pairs (1.2%) are related by three or more hits, and eight (0.1%) by four or more hits. None of the pairs were related by more than six hits.

Figure 2.

Percentage of hits between rice–Arabidopsis BAC pairs. One hit refers to a distinct match in rice and Arabidopsis. For 126 rice BACs analyzed, there are a total of 5957 rice–Arabidopsis BAC pairs linked by homologs. Among those pairs, 93.3% have one hit, 5.5% have two hits, and 1.2% have more than three hits.

We selected the 72 rice/Arabidopsis BAC pairs with three or more hits for further study of microcollinearity at the sub-BAC level. Of this set, 50 were collinear on both the rice and Arabidopsis genomes. (By chance, we would expect roughly one-third of the triplets, or 20 pairs, to be collinear.) We aligned the genomic sequences using PipMaker (Schwartz et al. 2000) and examined the results.

Table 1 summarizes this analysis. For each putative collinear segment, we list the accession numbers and approximate collinear size for both rice and Arabidopsis BACs, the number of times the collinear triples were interrupted by noncollinear gene pairs, and the brief identification of the Arabidopsis gene as reported in the MATDB database.

Table 1.

Groups of Collinear Segment Pairs Between Rice and Arabidopsis

| Group | Interruptions | Rice | Putative Function | Arabidopsis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAC | ORF | BAC | ORF | |||

| 1 | 3 | AP002882[1] | BAB39868.1 | putative receptor protein | AC011914_F14K14[1] | F14K14.4/AT1G68749 |

| (∼41 kb) | BAB39876.1 | putative phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase | (∼21 kb) | F14K14.1/AT1G68750 | ||

| BAB39877.1 | unknown protein | F14K14.18/AT1G68780 | ||||

| 2 | 2 | AP003338[1] | BAB39434.1 | receptor serine/threonine kinase PR5K | AB005247_MXA21[5] | MXA21_170/AT5G38280 |

| (∼36 kb) | BAB39435.1 | receptor serine/threonine protein kinase-like | (∼19 kb) | MXA21_150/AT5G38260 | ||

| BAB39439.1 | receptor serine/threonine protein kinase-like | MXA21_130/AT5G38240 | ||||

| 3 | 3 | AP003338[1] | BAB39434.1 | receptor serine/threonine kinase PR5K, putative | AC007152_F1O19[1] | F1O19.1/AT1G66930 |

| (∼36 kb) | BAB39435.1 | hypothetical protein | (∼30 kb) | F1O19.6/AT1G66980 | ||

| BAB39439.1 | hypothetical protein | F1O19_4/AT1G67000 | ||||

| 4 | 0 | AP003233[1] | BAB55519.1 | putative protein | AB012241_K18L3[5] | K18L3_30/AT5G37870 |

| (∼10 kb) | BAB55521.1 | putative protein | (∼29 kb) | K18L3_70/AT5G37910 | ||

| BAB55522.1 | putative protein | K18L3_90/AT5G37930 | ||||

| 5 | 0 | AP002483[1] | BAB16455.1 | putative protein | AL137189_F7J8[5] | F7J8_200/AT5G01220 |

| (∼23 kb) | BAB16456.1 | putative protein | (∼29 kb) | F7J8_180/AT5G01200 | ||

| BAB16458.1 | oligopeptide transporter-like protein | F7J8_160/AT5G01180 | ||||

| 6 | 0 | AP003311[1] | BAB40110.1 | putative protein | AL137189_F7J8[5] | F7J8_200/AT5G01220 |

| (∼23 kb) | BAB40111.1 | putative protein | (∼29 kb) | F7J8_180/AT5G01200 | ||

| BAB40113.1 | oligopeptide transporter-like protein | F7J8_160/AT5G01180 | ||||

| 7 | 6 | AP002540[1] | BAB43990.1 | ubiquitin-protein ligase E3-alpha-like protein | AL162874_T1E22[5] | T1E22_60/AT5G02300 |

| (∼103 kb) | BAB43991.1 | eceriferum3 (CEP3) | (∼37 kb) | T1E22_70/AT5G02310 | ||

| BAB44010.1 | metallothionein 2b | T1E22_140/AT5G02380 | ||||

| BAB44011.1 | putative protein | T1E22_150/AT5G02390 | ||||

| 8 | 7 | AP002522[1] | BAB03613.1 | putative protein | AL162971_T22P11[5] | T22P11_70/AT5G02480 |

| (∼20 kb) | BAB03618.1 | putative protein | (∼29 kb) | T22P11_130/AT5G02540 | ||

| BAB03624.1 | putative protein | T22P11_160/AT5G02570 | ||||

| 9 | 4 | AP002522[1] | BAB03613.1 | unknown protein | AC004684_F13M22[2] | F13M22.7/AT2G37570 |

| (∼38 kb) | BAB03618.1 | putative oxidoreductase | (∼12 kb) | F13M22.4/AT2G37540 | ||

| BAB03619.1 | hypothetical protein | F13M22.3/AT2G37530 | ||||

| 10 | 3 | AP003045[1] | BAB44058.1 | hypothetical protein | AC009326_MZB10[3] | MZB10.14/AT3G09110 |

| (∼34 kb) | BAB44062.1 | hypothetical protein | (∼8 kb) | MZB10.15/AT3G09120 | ||

| BAB44065.1 | hypothetical protein | MZB10.17/AT3G09140 | ||||

| 11 | 1 | AP003045[1] | BAB44060.1 | putative protein | AL137189_F7J8[5] | F7J8_100/AT5G01120 |

| (∼23 kb) | BAB44062.1 | putative protein | (∼9 kb) | F7J8_110/AT5G01130 | ||

| BAB44065.1 | putative protein | F7J8_130/AT5G01150 | ||||

| 12 | 0 | AP002523[1] | BAB17059.1 | putative glucosyl transferase | AC006282_F13K3[2] | F13K3.15/AT2G36750 |

| (∼2 kb) | BAB17060.1 | putative glucosyl transferase | (∼9 kb) | F13K3.17/AT2G36770 | ||

| BAB17061.1 | putative glucosyl transferase | F13K3.18/AT2G36780 | ||||

| 13 | 4 | AP002524[1] | BAB07963.1 | putative protein | AL022537_F4D112[4] | F4D11.180/AT4G32620 |

| (∼26 kb) | BAB07965.1 | putative protein | (∼13 kb) | F4D11.190/AT4G32610 | ||

| BAB07971.1 | putative protein | F4D11.200/AT4G32600 | ||||

| 14 | 4 | AP002482[1] | BAA99514.1 | hypothetical protein | AL078620_F23K16[4] | F23K16_50/AT4G39420 |

| (∼19 kb) | BAA99515.1 | hypothetical protein | (∼27 kb) | F23K16_60/AT4G39430 | ||

| BAA99516.1 | hypothetical protein | F23K16_80/AT4G39450 | ||||

| BAA99522.1 | cytochrome P450-like protein | F23K16_110/AT4G39480 | ||||

| BAA99523.1 | cytochrome P450-like protein | F23K16_120/AT4G39490 | ||||

| 15 | 0 | AP002743[1] | BAA99424.1 | phytochrome-associated protein PAP2 | AL07840_F19B15[4] | F19B15.110/AT4G29080 |

| (∼11 kb) | BAA99425.1 | hexokinase | (∼57 kb) | F19B15.160/AT4G29130 | ||

| BAA99426.1 | hypothetical protein | F19B15.180/AT4G29150 | ||||

For each group, GenBank accession numbers for rice and Arabidopsis BAC are followed by their chromosome location and approximate linkage size. Putative protein function information was retrieved from the MATDB database. Interruptions refer to the number of rice genes having Arabidopsis homologs that do not fall into the collinear region. The complete table can be accessed at http://www.genome.org.

From the perspective of the rice genome, the longest collinear group is 159 kb, and the shortest is 2 kb, with a mean length of 45 kb. For Arabidopsis, the corresponding figures are 61 kb, 6 kb, and 25 kb. However, these figures include regions that are interrupted by noncollinear Arabidopsis/rice homolog pairs. Considering only regions with 2 or fewer interruptions, the longest region of rice collinearity is 63 kb, with a mean length of 25 kb. Among the 10 collinear regions with no interruptions, the corresponding lengths are 26 kb and 16 kb.

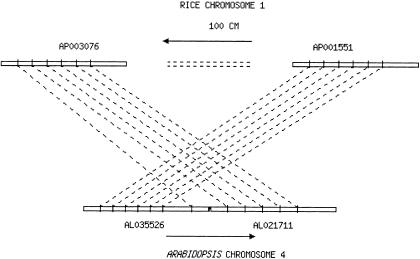

It is interesting to note that rice BAC clone AP001551 in group 21 and clone AP003076 in group 47 are both on Chromosome 1; the corresponding conserved segments on Arabidopsis AL035526 and AL021711 are adjacent on Arabidopsis Chromosome 4. When we combine these two groups, as shown in Figure 3, the conserved region has 11 homologs with conserved order in Arabidopsis and spans >130 kb. However, the rice BACs are thought to be more than 100 cM apart on the genetic map. Similar phenomena were observed between groups 7 and 8, groups 16 and 28, groups 23 and 40/46, and groups 49 and 50. In each case, BACs that are adjacent on Arabidopsis contain collinear segments with rice BACs from the same chromosome. However, in all cases, the homolog pairs are not consecutively linked, but are frequently interrupted by noncollinear pairs.

Figure 3.

Microcollinearity of linked Arabidopsis BAC clones with discontinued rice segments.

Groups 15 and 17 contain adjacent Arabidopsis BACs on Chromosome 4 that match to the same rice BAC on Chromosome 1. When we merge these groups, it extends the rice collinear segment to 91 kb and the Arabidopsis segment to 97 kb with 2 interruptions in the rice BAC. For other groups in which the matching Arabidopsis and rice BACs are on the same chromosome pairs, the distance between the BACs is at least 1 Mb on the basis of the physical and/or genetic maps. These microcollinear regions cannot be merged.

Because the Arabidopsis genome is highly duplicated, we noticed that the same rice region may correspond to two collinear regions in Arabidopsis, such as groups 2 and 3, groups 8 and 9, groups 10 and 11, groups 15 and 16, groups 20 and 21, and groups 40 and 41. The same phenomena were twice observed in rice as well. Groups 5 and 6, and groups 38 and 39, each involve an Arabidopsis segment that is collinear with two distinct regions on rice chromosomes.

Another interesting finding is that many of the collinear regions involve protein family clusters in both Arabidopsis and rice. For example, groups 38 and 39 show diverged copies of putative cytochrome P450 in both species, groups 22 and 24 show diverged copies of a putative Arabidopsis lipase and copies of a putative rice lipase, and group 12 contains three diverged copies of a putative Arabidopsis glucosyl transferase and three copies of a putative rice glucosyl transferase. Overall, the members of the cytochrome P450 cluster are >82% identical, the lipases are >87% identical, and the glucosyl transferases are >72% identical at the protein level. This finding indicates that clusters of related proteins in Arabidopsis tend to be similarly clustered in rice.

Search for Missing Homologs

It is possible that some of the BAC pairs containing only a single protein hit contain further regions of homology because of incomplete annotation of the rice and/or Arabidopsis genomes. To check whether we missed such regions, we selected 10 pairs of BACs that contained only one hit and aligned them at the nucleotide level using PipMaker. Of the 10 BAC pairs so aligned, 9 showed only the homolog that had been detected earlier, whereas 1 showed an additional region of alignment with a low similarity level of uncertain significance. From the above studies, we conclude that our protein level analysis has not significantly undercounted the number of collinear regions.

Simulation of Microcollinearity in Rice and Arabidopsis

Although we were able to identify small collinear clusters of putative homologous genes among rice and Arabidopsis, it is possible that this finding is the result of chance rather than the evolutionary conservation of gene order. To address this question, we simulated the probability of finding an Arabidopsis BAC homologous to a rice BAC under the model that genes are distributed at random along the genome and that there is no correlation between the position of a gene on the two genomes. We used a genome size of 115 Mb for Arabidopsis and 20 Mb for the corresponding annotated rice genome and assumed a gene density of 1 gene per 4.8 kb for Arabidopsis and 1 gene per 6.25 kb for rice, and that 58% of rice genes have homologs on Arabidopsis (based on the 126 rice BACs we studied). We used an average BAC size of rice of 150 kb and 75 kb for Arabidopsis.

We ran the simulation 10,000 times and sampled the results at each iteration. As shown in Table 2, the simulation predicts that the chance of finding a single rice/Arabidopsis homolog by random chance on a single rice BAC is almost 1, a value similar to our observations. However, for detecting linked clusters of three or more homologs the simulation predicts values 1–2 orders of magnitude lower than we observed, implying that the linked clusters that we detected in this study are the result of the conservation of gene order, and not the result of a random association.

Table 2.

Simulation of the Probability of Finding Hit (Homolog) of a Rice BAC to an Arabidopsis BAC

| 1 hit/BAC | 2 hits/BAC | 3 hits/BAC | 4 hits/BAC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/B/C (std) | A/B (std) | C (std) | A (std) | B (std) | C (std) | A (std) | B (std) | |

| Expected | 0.992 | 0.25 | 0.00099 | 0.00157 | 0.00014 | 0 | 0.00001 | 0 |

| (1.11e-16) | (0.32) | (0.003) | (0.0035) | (0.0011) | (0) | (0.0003) | (0) | |

| Observed | 1 | 0.055 | 5e-3 | 0.012 | 0.007 | 5e-4 | 2.7e-3 | 8.4e-4 |

(A) Number of homologs on BAC; (B) homologs are in order on BAC; (C) homologs are in uninterrupted order on BAC.

Std, standard deviation.

Microcollinearity at the Exon Level

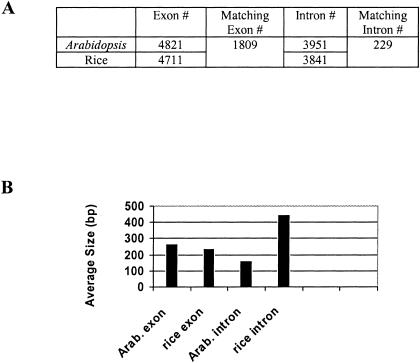

To determine the degree of collinearity between Arabidopsis and rice at the scale of an individual gene, we analyzed 989 putative rice/Arabidopsis homolog pairs identified earlier after removing paralog pairs, and compared the order of their exons based on the annotations in RGP and MATDB.

As shown in Table 3, a total of 7723 exons were examined. Of these, 1809 (23%) were present in both members of the pair, 2902 (38%) were present only in the rice homolog, and 3012 (39%) were present only in the Arabidopsis homolog. On examining the 989 rice/Arabidopsis homolog pairs, we found that 315 (32%) pairs had two or more homologous exons. In all such cases, the exons showed almost perfect collinearity. The exons in the two species were very similar in size, with a mean difference of 28 bp. However, introns tended to be larger in rice than in Arabidopsis, 449 bp for rice versus 164 bp for Arabidopsis, a 1.7-fold difference.

Table 3.

Exon-Intron Analysis of Rice–Arabidopsis Ortholog

We aligned 989 nonredundant rice–Arabidopsis ortholog pairs to reveal the exon-intron structure of each pair. Rice gene models were retrieved from RGP, and Arabidopsis gene models were retrieved from MATDB. (A) The number of exon, intron analyzed; (B) average size of exon, intron in rice and Arabidopsis.

DISCUSSION

We have systematically searched for microcollinearity in the presently available annotated genomic sequence in rice and Arabidopsis. Our strategy has been to identify putative homologs at the protein level, and then to study the order of those homologs on the genome.

Our findings indicate that genomic collinearity is present at the scale of individual genes and occasionally across short uninterrupted clusters of genes up to ∼26 kb in total length. However, longer segments of collinearity can only be found by allowing interruptions from noncollinear homolog pairs. Large-scale collinear regions of BAC size or larger were not found.

There have been extensive studies of duplication in the Arabidopsis genome (The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative 2000), where it has been shown that many regions are present twice in the genome. Our analysis of collinear segments at the sub-BAC level allowed for these duplicated regions. However, in most cases, for the collinear regions we found, the similarity within the Arabidopsis genome was less than the similarity between rice and Arabidopsis. Hence the duplicated regions do not affect our conclusions.

It has been suggested that the organization of the rice and Arabidopsis genomes are substantially different (Barakat et al. 1998). In Arabidopsis genes are fairly evenly distributed, but it is hypothesized that in rice genes are confined to clusters accounting for ∼12%–24% of the genome separated by large gene-poor regions. Our studies neither confirm nor contradict this hypothesis, but we have found that the introns in rice are substantially larger than their Arabidopsis homologs. This could explain part of the difference in size between the two genomes. However, it's worth noting that our assessment of gene structure is based on the third annotation party in RGP for rice and MATDB for Arabidopsis. These annotations may not be independent.

A limitation in this analysis lies in the fact that it is based on third-party annotations. Some of the rice genes were predicted based on similarity to proteins in other species, Arabidopsis among them. This may introduce correlations between the two genomes for which we have not accounted.

Microcollinearity can be used as a tool for annotating one genome based on annotations in another, as well as for positional cloning and mapping studies. Our studies imply that it is not possible to infer the large-scale gene order in the rice genome on the basis of Arabidopsis. Neither genomic assembly of rice based on the Arabidopsis sequence nor attempts to clone rice genes based on comparative mapping in Arabidopsis are likely to succeed.

On a positive note, we find substantial collinearity between the exons of individual rice genes and their Arabidopsis homologs. This validates the strategy of annotating individual genes in the rice genome using predicted and confirmed genes from Arabidopsis.

METHODS

Data Sets

Arabidopsis Annotated Proteins

Arabidopsis annotated proteins were retrieved from MATDB (MIPS Arabidopsis thaliana database, http://mips.gsf.de/proj/thal/db/) in July 2001. There are a total of 24,570 proteins on 1567 BACs.

Rice BAC Sequences

After removing overlapping sequence, 3011 (2543 on Chromosome 1) rice proteins on 126 BAC clones (108 on Chromosome 1) were retrieved based on the annotation of RGP (http://rgp.dna.affrc.go.jp/GenomeSeq.html) in July 2001.

Homology Search

Arabidopsis proteins homologous to rice proteins were identified by BLASTP analysis of rice proteins against Arabidopsis proteins. The Arabidopsis homolog is defined as the Blast hit to a rice protein with P value <10−5 for random chance match.

BAC Sequence Alignment

BAC sequences were compared using PipMaker (Schwartz et al. 2000) for identifying conserved segments. For each Arabidopsis and rice BAC pair, a mask file and an exon position file for Arabidopsis BAC sequences were provided for the analysis. Repetitive sequences were identified by RepeatMasker (http://ftp.genome.washington.edu/cgibin/RepeatMasker), and exon positions were retrieved from MATDB. Results were analyzed by percent identity plot (PIP) and dot plot.

Simulation of the Probability of Finding an Arabidopsis BAC Homolog to a Rice BAC Sequence

An ordered data set numbered from 1 to 24,570 is generated, symbolizing Arabidopsis proteins positioned on the chromosome. A second data set includes 3011 numbers, 1747 (58%) of which were randomly picked up from the Arabidopsis data set (1–24, 570) and the rest (1264) represented by 0. The second data set was randomly positioned in an order symbolizing rice proteins on the chromosome. Sets of 24 consecutive numbers on the first data set (symbolizing a BAC) were compared to their positions on the second data set. Two numbers separated by a distance of 16 or less on the second set were considered to be on the same BAC.

Acknowledgments

We thank Guanming Wu and Steve Schmidt for technical assistance. We are grateful to Dick McCombie, Manpreet Katari, and Harshawardhan Bal for useful discussions. This work was supported with funds from NSF DBI-9872644.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL lstein@cshl.org; FAX (516) 367-8389.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.194501.

REFERENCES

- Acarkan A, Robberg M, Koch M, Schmidt R. Comparative genome analysis reveals extensive conservation of genome organisation for Arabidopsis thaliana and Capsella rubella. Plant J. 2000;23:55–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 2000;408:796–815. doi: 10.1038/35048692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat A, Matassi G, Bernardi G. Distribution of genes in the genome of Arabidopsis thalianaand its implications for the genome organization of plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:10044–10049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan M, Murphy G. The small, the large and the wild: The value of comparison in plant genomics. Trends Genet. 1999;15:211–214. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01744-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, SanMiguel P, de Oliveira AC, Woo SS, Zhang H, Wing RA, Bennetzen JL. Microcollinearity in sh2-homologous regions of the maize, rice, and sorghum genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:3431–3435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos KM, Beales J, Nagamura Y, Sasaki T. Arabidopsis–rice: Will collinearity allow gene prediction across the eudicot–monocot divide? Genome Res. 1999;9:825–829. doi: 10.1101/gr.9.9.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodeweerd AMV, Hall CR, Bent EG, Johnson SJ, Bevan MW, Bancroft I. Identification and analysis of homologous segments of the genomes of rice and Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome. 1999;42:887–892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale MD, Devos KM. Plant comparative genetics after 10 years. Science. 1998;282:656–659. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller B, Feuillet C. Collinearity and gene density in grass genomes. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:246–251. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01629-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku HM, Vision T, Liu J, Tanksley SD. Comparing sequenced segments of the tomato and Arabidopsisgenomics: Large-scale duplication followed by selective gene loss creates a network of synteny. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:9121–9126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160271297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passarge E, Horsthemke B, Farber RA. Incorrect use of the term synteny. Nat Genet. 1999;23:387. doi: 10.1038/70486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin GM, Yandell MD, Wortman JR, Gabor Miklos GR, Nelson CR, Hariharan IK, Fortini ME, Li PW, Apweiler R, Fleischmann W, et al. Comparative genomics of the eukaryotes. Science. 2000;287:2204–2215. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski J, Quiros CF. Organization of an Arabidopsis thaliana gene cluster on chromosome 4 including the RPS2 gene in the Brassica nigragenome. Theor Appl Genet. 1998;96:468–474. doi: 10.1007/s001220050763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R. Synteny: Recent advances and future prospects. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2000;3:97–102. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(99)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Zhang Z, Frazer KA, Smit A, Riemer C, Bouck J, Gibbs R, Hardison R, Miller W. PipMaker—A web server for aligning two genomic DNA sequences. Genome Res. 2000;10:577–586. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.4.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarchini R, Biddle P, Wineland R, Tingey S, Rafalski A. The complete sequence of 340 kb of DNA around the rice Adh1–Adh2region reveals interrupted collinearity with maize chromosome 4. Plant Cell. 2000;12:381–391. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.3.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vision T, Brown DG, Tanksley SD. The origins of genomic duplications in Arabidopsis. Science. 2000;290:2114–2116. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5499.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]