Abstract

We present the results of a clinical trial that tested the efficacy of using motivational interviewing (MI) in a group format to promote adherence to antiretroviral medications and risk reduction behaviors (RRB) in 203 predominately African American HIV infected women. It was compared to a group health promotion program. Participants were followed for 9 months. Adherence was measured by MEMS®; and RRB by self-report. Controlling for recruitment site and years on ART, no significant group by time effects were observed. Attendance (≥7/8 sessions) modified the effects. Higher MI attendees had better adherence at all follow-ups, a borderline significant group by time effect (p = 0.1) for % Doses Taken on Schedule, a significantly larger proportion who reported abstinence at 2 weeks, 6, and 9 months, and always used protection during sex at 6 and 9 months. Though not conclusive, the findings offer some support for using MI in a group format to promote adherence and some risk reduction behaviors when adequate attendance is maintained.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Motivational interviewing, Antiretroviral adherence, Risk reduction behaviors

Introduction

Antiretroviral medications have transformed HIV to a chronic condition requiring life-long treatment. The effects of antiretroviral medications on prolonging life and preventing opportunistic infections have been well documented, and there is evidence that the resultant lower viral loads are associated with lower risks of HIV transmission to both unborn children and sexual partners [1, 2]. However, near perfect adherence is required to achieve these benefits and prevent drug resistance.

HIV infected women who are taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) have gender-related issues with self-management of their disease that can impact medication adherence and the adoption of risk reduction behaviors (RRB). For example, HIV positive women often have low incomes and consequently may be dependent on men or others for economic support. Women are at least in part, dependent on men for using condoms, an important HIV protective strategy. Women are often the caregivers for both their partners and children and in this role, often put caring for themselves behind caring for others. HIV positive women also have more depression than their HIV negative counterparts, and HIV positive men. Depression can diminish one’s ability to adhere to ART and can affect use of RRB in women [3, 4]. Women may also be grappling with their own or their partner’s substance abuse, which may affect their ability to take antiretroviral medications and cloud their ability to negotiate or use condoms if substance use is associated with sexual activity. Fear of stigma resulting from disclosure of HIV status, may impact medication taking behavior and insistence on condom use. Despite knowledge of the life prolonging effects of ART and the importance of condoms in preventing transmission, the barriers faced by women may affect motivation for adherence to antiretroviral therapy and adoption of RRB. There is also evidence to suggest a relationship exists between adherence to antiretroviral medications and use of risk reduction behaviors in both men and women [4-7]. Higher adherence is associated with fewer risky behaviors [6] and in women lower adherence was associated with inconsistent condom use [4]. Recent reports have demonstrated the importance of ART treatment as a form of HIV prevention. The resultant lower or undectable viral loads is associated with a lower risk of HIV transmission [1, 8]. Thus, an intervention that combines these behaviors could have important clinical and public health implications.

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a client centered counseling method that helps clients resolve ambivalence toward and build motivation for behavior change. MI counseling has been successful in changing many health behaviors including substance use, fruit and vegetable intake, and physical activity [9-12]. More recently MI has been used with HIV positive persons to address substance use, [13, 14] medication adherence, [13, 15, 16] and safer sex preventive behaviors [14, 17-21]. In most prior studies it has been conducted in one-to-one counseling sessions, however, we adapted this method for the group format drawing from the experience of Ingersoll and Wagner [22] who used MI for substance abuse treatment groups and Morrison-Beedy and colleagues [23] who used motivational enhancement for safer sex with adolescents.

The purpose of this study was to determine the efficacy of a group intervention based in MI in promoting both adherence to antiretroviral medications and risk reduction behaviors in women infected with HIV. We hypothesized that the MI group, when compared with a Health Promotion Program (HPP), immediately (2 weeks), and 3, 6, and 9 months post intervention would: have higher mean adherence rates; report more frequent mean use of risk reduction behaviors; have higher mean CD4 lymphocyte counts and lower HIV viral load levels as measured by chart reviews.

Methods

Setting and Design

The KHARMA (Keeping Healthy and Active with Risk Reduction and Medication Adherence) Project took place at five HIV clinical sites in a large southeastern metropolitan city. The primary recruitment site was an infectious disease clinic at a large public hospital system that serves over 4,000 HIV infected men, women, and children annually. About 25% of these clients are women, and 73% are African American. The other sites were an HIV/AIDS non-profit service organization, a hospital based infectious disease clinic, a health department HIV clinic, and a private practice that provided care for HIV infected persons. The study was a randomized controlled behavioral clinical trial in which participants were randomized within sites to the intervention or control condition using a computer generated randomization scheme. After a short pilot study to test the intervention and study procedures, recruitment for the main study began on January 10, 2005. Final assessments were completed in January 2008. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Emory University and research committees at the sites, when required. The Data Safety and Monitoring Board met annually to review data and monitor recruitment and retention. No serious adverse events occurred as a result of this project.

Recruitment

Women were recruited for the KHARMA Project through providers, nurse educators, case managers, and self-referral at the sites. Potential participants were asked to have their providers sign a referral form that stated they were prescribed antiretroviral medications. Eligibility criteria consisted of: (1) HIV infected; (2) female by birth; (3) prescribed antiretroviral therapy; (4) 18 years of age or older; (5) English speaking; (6) mentally stable as determined by a screening assessment; (7) willing to participate by completing computerized assessments, use electronic drug monitoring (EDM) caps, be randomly assigned and participate in group sessions. Interested women signed an informed consent form and completed a screening interview. We did not use low adherence as entry criterion because it has been well documented that medication adherence decreases the longer a patient is on the medication; therefore maintenance of adherence is important for all patients.

Study Procedures

Participants who met the eligibility criteria received a MEMS 6 TrackCap® (Aardex Ltd, Zug, Switzerland) for electronic drug monitoring. Participants began using the MEMS 6 Track Cap® immediately upon enrollment into the study. They then waited with other newly enrolled participants until a group of 16–18 women accrued from the sites. At this time, the new participants were scheduled for a baseline assessment. Following the baseline, each woman was randomly assigned to either the intervention (MI) group or the control (HPP) group. In order to gather baseline adherence information, participants used the MEMS 6 Track Cap® for a minimum of 2 weeks prior to the baseline assessment and randomization. Groups started within 1–2 weeks of baseline and met for 8 weekly sessions. Over the course of the project nineteen MI and HPP groups were formed. Follow-up assessments occurred at 2 weeks (immediate), 3 months, 6 months and 9 months after the final group session. Assessments were conducted using audio computerized assessment self-interview (ACASI) technology. We conducted face-to-face interviews to obtain additional information about medication complexity, and medication taking over previous 1, 3, 4, 14, and 30 day periods. Participants also returned for monthly downloads of the EDM caps and the completion of a short in-person questionnaire on MEMS 6 Track Cap® use. Participants received $25 for each of the five assessments and transportation tokens and snacks for EDM cap downloads. Child care was provided during group sessions and for assessments.

Intervention and Control Conditions

Intervention

The KHARMA intervention consisted of eight group sessions using motivational interviewing delivered in a group format. It was designed to empower women to make decisions and develop strategies about taking ART as prescribed and consistently using risk reduction behaviors, such as condom use and to overcome resistance/ambivalence to both. The sessions lasted about 1.5–2 h, and were led by trained MI nurses. The first and last session focused on both adherence and risk behavior, three sessions were devoted to adherence only and three to risk reduction behaviors only, including a session on disclosure which is important to risk reduction as well as adherence. Each session included a discussion of goals and goal setting related to the topic. MI techniques were incorporated into every session. In keeping with the autonomy support spirit of MI, participants as a group chose which topic they wanted to address first. The majority of groups (n = 14) chose medication adherence as the first topic. Table 1 contains an outline of the session topics and content.

Table 1.

MI group session topics

| Session topic | Content and MI strategies |

|---|---|

| 1. Introduction, group guidelines, exploration of lifestyles |

Group introductions, icebreaker. Explore day-to-day experiences with medication taking, and practicing safer sex RRB. Discuss personal values and how they also fit into one’s life. Introduction to goal setting |

| 2. ART awareness: the good things and the not so good things |

Identify barriers and facilitators for taking ART. Revisit personal values and discuss connections between current medication taking and values. Goal setting |

| 3. ART adherence: change and exploring goals | Explore personal motivation for ART adherence. Problem solve strategies to reduce barriers to adherence. Goal setting |

| 4. Sharing successes and ART strategies | Explore previous successes in lifetime (graduation, etc.); draw from these to enhance medication taking success. Examine self-confidence to maintain strategies. Explore values and relate to current medication taking behavior. Goal setting |

| 5. Risk reduction behavior: knowledge and skills | Discuss ‘truth or lies’ about all risk reduction methods. Male and female condom skill building. Goal setting |

| 6. Risk reduction behavior: balance and negotiation | Decisional balance on the pro/cons of using RRB. Explore personal motivation and self-confidence to use RRB consistently. Team consult with role play safer sex negotiation. Goal setting |

| 7. Disclosure of HIV status: to tell or not to tell | Using a case scenario, discuss the good and not so good things about disclosure, and related to sexual behavior. Explore personal self-confidence to disclose and role play disclosure scenarios. Goal setting |

| 8. Summary and termination: putting it all together with goals and values |

Safer sex behavior continuum. Identify one’s core personal values and link them with current and future medication adherence and use of RRB. Group closure and goodbyes. Certificates of completion. Set long term goals |

Control Condition

The HPP control group sessions were equivalent in length and time to the MI group and were led by trained nurses and a health educator. This group used health education techniques of lecture/discussion/educational games and focused on nutrition, exercise, stress recognition, and women’s health issues tailored to the HIV positive woman. Participants received a manual containing content and supplementary materials for each session. Adherence and RRB were not addressed in the HPP and facilitators were instructed to redirect the group if these issues came up.

To promote retention, participants in both conditions received monetary and non-monetary incentives for attendance at each session. Non-monetary incentives included meals, transportation tokens, toiletry items, childcare, water bottles, and a tote bag received at the first session. In addition, a massage therapist conducted shoulder, neck or chair massages before two sessions and a beauty consultant demonstrated make-up and skin care tips before one session. Participants in the intervention group also received a purse size inspirational calendar, motivational journal, motivational adherence video [15], male and female condoms, dental dams, and lubricants. The intervention and health promotion sessions are described in detail in Holstad et al. [24].

Facilitator Training and Monitoring

Motivational group facilitators received a 24-h training program presented over 1 week by the principal investigator (mmh). The program included motivational interviewing theory and practice, as well as information about HIV, antiretroviral medications, and group facilitation/management skills. There were eight nurses trained throughout the project. All facilitators had extensive role-play practice that culminated in leading two groups made up of standardized patients. Standardized patients (SP) [25] were actresses trained to portray HIV positive women and were also trained to evaluate and provide feedback about the facilitator’s skills in MI and group management. Each session was videotaped and reviewed by the principal investigator who is an experienced MI trainer. She met with each facilitator to discuss the tapes and feedback from the SP. All nurses were deemed ready to facilitate the MI groups after the SP experience. Regular updates and booster training were provided to facilitators throughout the study. In addition, a therapist trained in MI reviewed 20% of both the MI and HPP facilitators tape-recorded group sessions and coded them using a structured coding form. The form measured adherence to both MI skills and the spirit of MI and one form was completed per group session. Overall, the MI facilitators had higher MI consistent scores than the HPP group facilitators indicating consistent use of MI throughout the project and no drift into the control group.

HPP group facilitators received extensive training regarding HIV in women, stress and depression, nutrition, exercise, and women’s health. Four control group facilitators were trained during the project, and each was required to pass a comprehensive test of the content for the groups with a score of at least 80%. In addition, they received group facilitation/management training similar to the MI nurses but it did not contain any MI specific skills. Regular meetings with the HPP facilitators were held to discuss any topical updates and group management issues. There was no crossover between MI and HPP facilitators and groups.

Measures

Electronic Drug Monitoring (EDM)

One medication from the regimen was electronically monitored using the MEMS® cap and an algorithm was used to determine which medication would receive the cap. In general, that medication was the primary protease inhibitor (PI), or the non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) if a PI was not prescribed. A sticker was placed on the monitored medication bottle and the participant was instructed to write dates and times on the sticker when the medication was pocketed, or if the cap was opened by mistake. At each download, information on this sticker was reviewed and an EDM questionnaire was completed. The information collected on the questionnaire included changes in medication regimen, problems with the cap, if someone else had administered the medication, and if the medication had been stopped. If the medication had been stopped, the participant was asked who stopped it and the reason, and if it had been restarted. If the participant was taken off the medication and brought the cap to the study office, it was stored until the participant re-started medication and those days were marked as ‘non-monitored.’ EDM data were adjusted by setting certain days as ‘non-monitored’ on which the following events occurred: cap malfunction, lost cap, medication stopped by healthcare provider, someone else administered the medication (e.g., hospital, group home), incarceration, pocketing pills, reported exclusive use of pill box, and excessive openings (a form of cap malfunction defined as more than twice the dose plus one). The EDM data were captured over time in phases consistent with the five assessment periods. Data from the MEMS report on the Percentage (%) of Prescribed Doses Taken and Percentage (%) of Prescribed Doses Taken on Schedule were used for this analysis. The MEMS Track® caps were used by participants during the entire study period (about 13 months) including 2 weeks prior to the baseline to obtain an estimate of baseline adherence.

CD4 counts and viral loads are indicators of the immune status and HIV viral activity. Both are expected to improve with adherence to ART; however, the intended effect of ART, to prevent viral replication, is more directly assessed by the viral load. Because of their high cost, we used data extracted from participants’ medical records during the time they were enrolled in the study. Dates that the laboratory tests were drawn were grouped according to proximity with the study assessment periods. For example, labs drawn as close as possible and prior to or on the day of the baseline assessment were classified as the baseline CD4 and viral load results. The median was about 27 days prior to the baseline. Participants did not always have both tests performed on the same date and therefore may have only had one test result available during an assessment period. The standard of care is to order these tests every 3–4 months once a patient has stabilized. Consequently, by the end of the follow-up period, participants had fewer labs available that corresponded to study time points. For the analysis, we used the Percent of CD4 cells (<14% is the CDC criteria for AIDS [26]) and we set the level of undectable at <400 copies per milliliter (<2.6 log10). The type of viral load studies did vary at the sites (RNA and bDNA) and the lower limit of detection possible changed over the 3 year study period. This level was used because it was the most inclusive.

Condom use and risk reduction behaviors were measured using our modified version of the Centers for Disease Control Sexual Behavior Questions [27]. This questionnaire contains 58 items about current sexual activity, sexual activity with a main partner and a casual partner, male and female partners. Examples of behaviors addressed are vaginal, oral, and anal sex; use of alcohol, drugs before sex; use of protection (such as male condom, female condom, and dental dam) during sex. Items require a ‘yes/no’ for use of behavior and scaled responses for frequency of behavior. We used the following items for the primary outcome analysis: reasons for sexual inactivity in the past 3 months (no opportunity, broke up with partner, practicing abstinence, other); number of sexual partners in the past 3 months, frequency of use of protection with sexual activity in the past 3 months (always vs. all else). To assess substance use we adapted items from two instruments, the HIVNET Risk Assessment developed with NIH funding by Statistical Center for HIV/AIDS Research and Prevention (ACHARP) for the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) [28] and the Elicitation of Compliance and Adherence Behaviors Survey (ECAB) [29]. The Substance Use Questionnaire contained 35 items regarding use of all types of substances such as alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, including injection drug use. One item was used for the primary analysis about frequency of getting high or having a few drinks immediately before or during sex in the past 3 months (never, occasionally, often, all of the time, don’t know). Because there was virtually no self-reported injection drug use (IDU) (n = range 0–2) and very few women who reported anal sex (n = range 5–10) over the course of the study we did not include these variables in the RRB analyses.

Depression scores were measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [30]. It consists of 20 items that measure current depressive symptoms. A score of 16 or greater is consistent with depression. Mean depression score for the sample was 16.4. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability of this scale for our sample was 0.90.

Data Analyses

We conducted preliminary analyses to identify treatment group differences in mean baseline measures using independent samples t-tests for continuous data and chi-square for categorical data. Linear and generalized linear mixed models were used to test the effect of group, time, and group by time interaction for the outcomes (Stata 10). This method allows the use of all available data at each time point in the analysis of repeated measures data (i.e., intent-to-treat). We analyzed the data for treatment effects (MI vs. HPP) in both the total group and in a subgroup of those with adequate attendance when it was clear from the visual inspection of the patterns that attendance changed the nature of the effect. We defined adequate attendance as attendance in at least seven of the eight sessions.

Due to the fact that the study was not powered for three way interactions, i.e. did not anticipate the effects of poor attendance, we were unable to perform a formal assessment of attendance as a moderator of the effect. In addition, we could not expect significant group* time interactions in these subgroup analyses due to the reduced sample size. Thus, we explored time-specific group comparisons, based on the model estimates, in order to further characterize possible treatment effects. Although preliminary, these results are important for future studies of MI in determining the amount/dose of intervention needed to produce the required effect in this population.

Results

Participants

As seen in Fig. 1, 391 women were referred to the KHARMA project, 249 were screened and 207 completed a baseline assessment, and randomized into one of the 19 intervention or control groups. There were 12 withdrawals (two more in the MI than control group), three each were due to deaths, work conflicts, loss of interest; two were due to poor health; one person moved out of state. In general, 118 (58.1%) of the participants in both groups attended seven or more sessions. The MI group sessions had better attendance (totals ranged from 76 [73%] for Session 5–84 [81%] for Session 3) than the control group sessions (range of 67 [65%] for Session 8–77 [75%] for Session 1), however there was one group where no MI participants attended any sessions. Overall, we have baseline data on and at least one follow-up assessment (including EDM data) on 203 of the 207 (98%) participants and all data were included in the final analyses.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of KHARMA project recruitment, allocation, and retention

The characteristics of these 203 participants are displayed in Table 2. They ranged in age from 18 to 68 with a mean of 43.5 years. The majority of the women was African American, unmarried, unemployed, and had very low income. About half the participants reported being sexually active at the time of the baseline assessment. Based on the results of treatment group comparisons, the groups did differ significantly at baseline on two variables. Those in the HPP group had been HIV positive somewhat longer (M = 10.5 years) than those in the MI group (M = 8.4 years) and were on antiretroviral medications longer (6.8 years vs. 5.4 years). Since both of these variables also had mild correlations with various outcomes, we considered them as possible covariates in the analysis. Both variables were also highly correlated, thus we used only years on ART rather than both to avoid multicollinearity. CESD scores were significantly but mildly correlated (r <0.2) with adherence measures, but not significantly different between treatment groups at baseline, thus we chose not to control for depressive symptoms. Adherence was also consistently different by study site, due to the fact that sites varied on the education and preparation given to patients who are on ART. Thus we controlled for a main effect of site using a categorical covariate (main site vs. other).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of KHARMA participants who completed at least one follow-up assessment (n = 203)

| Variable | MI group (n = 101) | HPP group (n = 102) | Total (n = 203) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 43.5 (9.1) | 43.5 (9.2) | 43.5 (9.2) |

| Number of years HIV+ | |||

| Mean (SD)a | 8.4 (5.9) | 10.5 (6.3) | 9.5 (6.2) |

| Number of years on ARVs | |||

| Mean (SD)b | 5.4 (4.5) | 6.8 (5.1) | 6.1 (4.9) |

| Ethnicity n (%) | |||

| African American | 92 (91.1) | 97 (95.1) | 189 (93.1) |

| White | 6 (5.9) | 1 (1.0) | 7 (3.4) |

| Other | 3 (3.0) | 4 (3.9) | 7 (3.4) |

| Education n (%) | |||

| <High school | 17 (16.8) | 22 (21.6) | 39 (19.2) |

| High school | 55 (54.5) | 54 (52.9) | 109 (53.7) |

| >High school | 29 (28.7) | 26 (25.5) | 55 (27.1) |

| Employment n (%) | |||

| Employed | 17 (16.8) | 15(14.7) | 32 (15.8) |

| Marital status n (%) | |||

| Married/committed | 27 (27.0) | 28 (27.5) | 55 (27.2) |

| Never married | 26 (26.0) | 29 (28.4) | 55 (27.2) |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 47 (47.0) | 45 (44.1) | 92 (45.5) |

| Children n (%) | |||

| Yes | 90 (89.1) | 90 (78.4) | 170 (83.7) |

| Median, range | 3 (1–7) | 3 (1–9) | 3 (1–9) |

| Annual Income n (%) | |||

| ≤$10,000 | 65 (67.0) | 67 (67.0) | 132 (67.0) |

| >$10,000 | 32 (33.0) | 33 (33.0) | 65 (33.0) |

| Sexual identity (%) | |||

| Heterosexual | 82 (81.2) | 78 (76.5) | 150 (77.7) |

| Gay, homosexual | 2 (2.0) | 3 (2.9) | 5 (2.6) |

| Bisexual | 5 (5.0) | 3 (2.9) | 8 (4.1) |

| None of above/unsure | 12 (11.9) | 18 (17.6) | 30 (15.5) |

| Sexually active (past 3 months) (%) | |||

| Yes | 50.5 | 56.9 | 53.7 |

| Depression: CES-D total | |||

| Mean (SD) | 15.6 (12.0) | 17.2 (11.5) | 16.4 (11.7) |

| CD 4 percent | |||

| Mean (SD) | 20.1 (9.9) | 22.1 (13.6) | 21.2 (12.0) |

| Viral load (% non-detectable) | 70.9 | 72.3 | 71.6 |

| Percent of prescribed doses taken | |||

| Mean (SD) | 73.5 (33.5) | 74.9 (31.8) | 74.2 (32.6) |

| Percent of prescribed doses taken on schedule | |||

| Mean (SD) | 58.2 (36.9) | 59.5 (36.9) | 58.9 (36.8) |

Groups differ (F = 5.74, df = 1,200, p = 0.017)

Groups differ (F = 4.66, df = 1,200, p = 0.032)

Adherence

Data from the % of Prescribed Doses Taken and the % of Doses Taken on Schedule from the MEMS® report were used in the analysis. When compared to the desired 95% adherence level [31], adherence rates were low; ranging from 75 to 58%. There was a significant decline in adherence in both groups over time in both % Doses Taken (F = 19.04, df = 4,660, p < .0005) and % Doses Taken on Schedule (F = 23.45, df = 4,667, p < 0.0005), however the total group exhibited no significant group*time interaction effects.

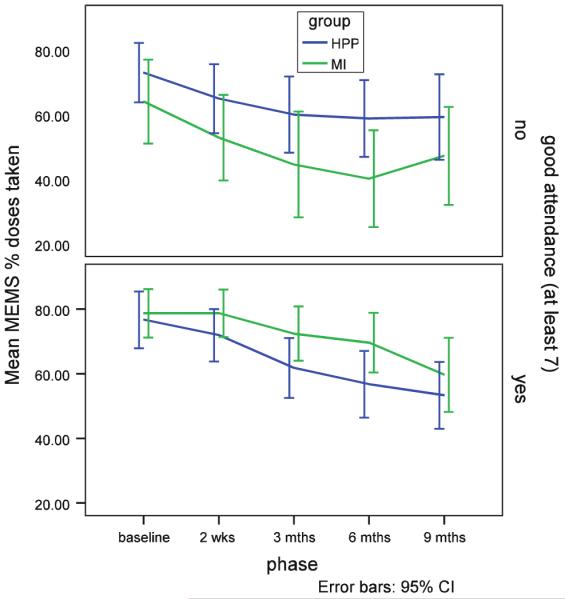

Attendance was visually examined as a possible modifier of the effect for all adherence measures (MEMS, CD4, viral load), but a clear difference in pattern of results was only evident for the MEMs measures, indicating that the benefit of MI was only evident in those with adequate attendance, in fact the effect was reversed in those with less attendance (Figs. 2, 3). Thus we analyzed the treatment group differences in only those subjects with adequate attendance (n = 118) (the lower graph in both figures). In this subgroup, there was a borderline group by time effect for the % of Doses Taken on Schedule (F = 1.84, df = 1,409, p = .12), but no significant interaction effect was observed for % Doses Taken. There were significant declines in adherence for both indicators in both groups, however, the MI group had higher % of Doses Taken and % of Doses Taken on Schedule at all time points; the differences in % Doses Taken on Schedule were significant for the 3 month (59.4% vs. 43.1%; t = 2.05, df = 198, p = .04) and borderline for the 6 month (55.0% vs. 40.1%; t = 1.81, df = 199, p = .072) assessments.

Fig. 2.

Mean percentage of doses taken by attendance for the MI and HPP groups

Fig. 3.

Mean percentage of doses taken on schedule by attendance for the MI and HPP groups

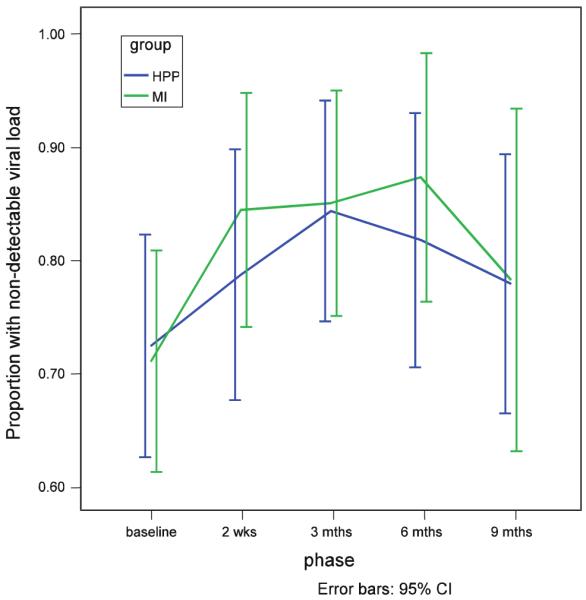

CD4 and Viral Load

As noted above, CD4 and viral load results are expected to improve with high levels of adherence. These provide clinical evidence of adherence and are presented for that reason. The average CD4 Percent for both groups was well above 14%, the criteria for AIDS. The average viral load (log) results were at or below the detectable range of <2.6 log10. Again, no significant group*time interaction effect was observed for the total group for either measure. However, mean percent of CD4 cells was lower in the MI group at all time points, and time specific group comparisons indicated that the difference was marginally significant at 3 months (t = −1.73, df = 317, p = .085) and significant at 9 months (t = −2.10, df = 355, p = .037) (Fig. 4). With respect to viral load (log), a greater proportion of those in the MI group had undetectable viral load (log) at all time points, although none of the time-specific group comparisons were significant (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Mean CD4 percents for MI and HPP groups

Fig. 5.

Proportion of those with an undectable viral load (log) for MI and HPP groups

Risk Reduction Behaviors

For the RRB outcomes of abstinence, use of protection in the past 3 months, and substance use associated with sex in the past 3 months there was no significant group by time effects in the analyses of the total sample. As with the adherence measures, attendance appeared to be a possible modifier by inspection of the patterns for abstinence and protection use, so those items were further explored by analyzing the data in only those with adequate attendance. In this smaller group of subjects (n = 118), there was no significant group by time effects for either abstinence or use of protection. However, the time-specific group comparisons showed the expected effects, with a larger proportion of MI attendees reporting practicing abstinence at all follow-up points. This difference was significant at the 2 weeks (Z = 2.58, p = .010), 6 month (Z = 2.05, p = .041) and 9 month (Z = 2.25, p = .025) follow-ups. Similarly, a greater proportion of MI attendees reported always using protection in the past 3 months at all time points, and the differences were significant at the 6 month (Z = 2.10, p = .036) and 9 month (Z = 1.91, p = .056) time points.

Discussion

We examined the efficacy of a motivational group intervention based in motivational interviewing and delivered by trained nurses to promote adherence to antiretroviral medications and use of risk reduction behaviors. The sample consisted of primarily African American women who had a low income and had been HIV infected for about 9 years and taking antiretroviral medications for an average of about 6 years. We believe this is one of the first studies to test a group motivational intervention focused on adherence to these two important outcomes for HIV infected women. Medication adherence was measured directly by electronic monitoring and indirectly by means of CD4 and viral load results abstracted from medical records. Overall, medication adherence was well below the 95% rate recommended to maintain health and prevent opportunistic infections [31]. Consistent with others’ findings, adherence in this sample significantly declined in both groups over the 9-month post-intervention follow-up period.

Average CD4 percent counts were well above 14% and average viral load results were at or below the detectable range of <400 copies per ml (<2.6 log10). A greater proportion of the MI group had undectable viral load (log) at all time points, but this was not statistically significant. The HPP group tended to have a higher mean CD4 percent at each assessment point.

In order to determine the efficacy of the MI group intervention if received as intended and the consequent need for dosing or retention strategies in future studies, we examined adequate attendance (≥7 sessions) in a sub-sample from both groups as a possible modifier of the effect of the intervention on adherence and RRB outcomes. With respect to ART adherence, there was a borderline group by time effect for % of Doses Taken on Schedule. High MI attendees had higher % Doses Taken and % Doses Taken on Schedule at all time points, compared to controls, however this difference was only statistically significant at 3 months.

With respect to use of RRB, those with adequate attendance exhibited the expected effects on abstinence and use of protection. Although there was no significant group by time, group, or time effects, most likely due to the reduced sample size in between group comparisons, a significantly larger proportion of high MI attendees reported practicing abstinence, the safest sexual behavior, at all follow-up time points except 3 months. Also a significantly greater proportion of attendees reported always using protection during sex at the 6 and 9 month final follow-up periods. Of note, is that a large subsample was exposed to a mandated “Prevention with Positives” initiative at the primary recruitment site.

Use of MI on a one-to-one basis has been efficacious for promoting ART adherence. DiIorio et al.[15] tested a 5-session MI intervention led by trained nurses and found a significant group by time improvement in adherence at the 8th month, which was sustained to the 12th and final follow-up. Parsons, et al. [13] employed eight individual MI and cognitive behavioral skills training (CBST) sessions led by trained master’s level counselors to promote adherence in hazardous drinkers. They found an improvement in both adherence and clinical indicators of VL and CD4 count at 3 months, however only adherence was sustained at the final 6 month follow-up. Adherence was measured by self-report for a 2-week period prior to the assessment points. Golin and colleagues [16] compared the efficacy of an adherence intervention that included two individual MI sessions versus educational sessions. After 12 weeks of follow-up, they found that the MI group improved adherence and the control group decreased adherence levels (p = .10) but there was no statistically significant differences in adherence rates between the groups at the 12 week final follow-up. When they controlled for ethnicity, those in the MI group had a 2.75 times higher odds of obtaining 95% or greater adherence than the controls. We found a similar pattern of adherence decline, over the 9-month post intervention follow-up period, however the high MI group attendees maintained better adherence levels than their HPP counterparts. Like Golin and colleagues [16] we also found no significant difference between groups in viral load, but more of the MI group had undectable viral load levels at all follow-ups. Both of the above studies included men and women, whereas KHARMA was specific for HIV infected women.

MI has also been used to promote safer sex behaviors in HIV infected men and women. Some studies are ongoing [18, 19, 21] however others report promising results. Fischer, Fisher, Cornman, Amico, Bryan, and Friedland [17] trained health care providers to provide a brief (5–10 min) MI-based counseling session on reducing unprotected sex at each clinical encounter with patients over an 18 month follow-up period. Compared to the standard of care, those who received the intervention significantly reduced unprotected vaginal and anal intercourse and insertive oral sex, while those behaviors significantly increased in the control group. In contrast, an intervention using social workers trained in MI within an existing clinic structure was not effective in promoting preventive behaviors in HIV infected clients. Possible reasons included additional work load for the already busy social workers, poor understanding of the program by patients, reluctance and lack of incentives for patients to stay after the provider appointment for additional counseling [20].

Our findings regarding abstinence were unexpected. Abstinence was included as a behavior for discussion in the groups, and apparently seen as a viable and the safest option by many women. Few studies have reported on abstinence in HIV infected women. Since the mean age of the group was 43.5 years, the peri-menopausal range, perhaps women felt less interest in sex and the effort required for safer sex negotiation and use was not worth it for their level of interest. Or maybe they found courage to say no to their partners related to increased self esteem or peer support from the groups.

The interventions we found that use MI with HIV infected persons have focused on one-to-one counseling and included either men or both men and women. A group component within the SMART/EST Women’s Project for HIV infected women, though not based in MI, was found to improve self-reported adherence when compared to individual based intervention containing the same content [32], thus highlighting the importance of group interventions for HIV positive women. The authors suggest that the group may have exerted effects due to increased emotional expression and support. All women in KHARMA intervention and control groups experienced the emotional support of a group and this support may have contributed to lower group differences in some of the outcomes.

We did note that those with high MI group attendance demonstrated better outcomes. MI is an interpersonal experience and one must be present to engage in this experience. MI techniques promote collaboration, autonomy, acceptance, and self-confidence to deal with ambivalence regarding a behavior change in a non-confrontational manner. In high attendees, these techniques might have contributed to the overall higher mean adherence levels and greater use of protection during sexual activity. On the converse, in low attendees, the reverse occurred; those with an inadequate dose of the group MI had poorer outcomes than the control group.

Our intervention tested MI in an 8-session group format led by trained nurses. Though not conclusive, the findings provide some support for the efficacy of MI in a group format for both improving adherence, particularly to dose scheduling, and use of abstinence and protection/condoms when consistent attendance is maintained. The incorporation of these two important strategies for HIV-infected women is essential to self-care of this chronic disease. In addition, the control group in this study was a strong health promotion program tailored to the needs of HIV infected women. It is possible that, because it focused on health related variables (nutrition, exercise, stress, women’s health), overall health awareness increased in this group and translated into improved self-care behaviors such as adherence and safer sex. Perhaps the use of EDM and monitoring of medications could also have stimulated adherence in the control group. Thus, improvements were seen for CD4 cells in HPP, and greater differences in outcomes were not seen between groups or over time. In the future, a combination of both group topics into a comprehensive health program for HIV infected women that employs MI seems reasonable, particularly with the increase in morbidity due to cardiovascular and metabolic effects of the antiretroviral medications. Other research might compare use of MI in a group format with traditional individualized MI, to promote both ART adherence and use of risk reduction behaviors and compare costs of the two formats.

Limitations

The main limitation of the current study was that it did not anticipate the effects of attendance, and thus the significance tests we were able to perform in many cases were underpowered. In addition, it did not appear to be adequately powered for binary outcomes such as viral load or most of the risk reduction behaviors, which generally require higher sample sizes than continuous measures such as EDM or CD4. Clearly future studies will need to attempt to accrue larger samples in order to demonstrate the true efficacy of MI over and above the effects of HPP.

In 2006, our main recruitment site implemented an ongoing “Prevention for Positives” initiative where all providers were required to elicit and document discussion about risky behaviors with each patient every 12 months. When indicated, patients were referred for risk reduction education and counseling. Our results may be impacted by the addition of this program. Given this occurred for women in both groups, it might have diluted between group differences. In addition, risk behaviors in this study were measured by self-report, and could be subject to bias from poor recall or social desirability.

Due to cost constraints, laboratory results were extracted from medical records and dates of lab tests did not always correspond in time to follow-up assessments. As the study progressed, there were fewer lab data for the 9 month assessment period. In the future blood draws consistent with the follow-up periods are recommended.

We monitored adherence primarily using the MEMS® Track Cap for electronic drug monitoring. Participants were asked to use this cap during the 13 months while enrolled in the study. The cap is cumbersome to use, and affects the portability of one’s medications. Therefore, participants may have skipped using their caps for periods of time during the study. In addition, caps can malfunction, rendering data unavailable. Since many patients use pill boxes or pill trays to facilitate their adherence, it is difficult to remember to open the cap when removing pills from the pill box. For these reasons, future researchers who choose to use EDM might consider shortening the time for EDM, or using newer more user-friendly technology available to conduct EDM.

The study participants are primarily low-income African American women in their midlife years and though they represent the predominant socio demographics of HIV infected women in the Southeast and the United States, we cannot generalize to other racial, ethnic, or younger age groups. The age may also reflect the nature of the primary recruitment site, which primarily cares for patients with an AIDS diagnosis, typically acquired after being HIV-infected for many years, as well as the now chronic nature of HIV disease.

The limitations of the project are offset by several strengths. The use of ACASI methodology to promote participant privacy and confidentiality in responses, high follow-up retention rates and lack of differential attrition, and attention to monitoring fidelity to the intervention help to strengthen the external validity of the findings. Our findings, though not definitive, offer some support for the efficacy of MI in group format to improve both adherence and some risk reduction behaviors, when good attendance is maintained.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Nursing Research R01 NR008094. We wish to thank the women who participated in this project and the providers and staff of the clinics from which we recruited and conducted the study. We also acknowledge the work of the KHARMA Project staff, including Bridget Jones, Carol Corkran, Sally Carpentier, Versey McLendon, Lisa Weaver, Kate Yeager, Samaha Norris, Ilya Teplinskiy, and Frances McCarty.

Contributor Information

Marcia McDonnell Holstad, Nell Hodgson School of Nursing, Emory University, 1520 Clifton Road, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA.

Colleen DiIorio, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA.

Mary E. Kelley, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA

Kenneth Resnicow, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2029, USA.

Sanjay Sharma, School of Medicine, Emory University, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA.

References

- 1.CDC Effect of antiretroviral therapy on risk of sexual transmission of HIV infection and superinfection: centers for disease control and prevention. 2009 September; [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC Recommendations for use of antiretroviral drugs in pregnant HIV-infected women for maternal health and interventions to reduce perinatal HIV transmission in the United States. 2009 cited 2009 October 18. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Remien RH, Exner T, Kertzner RM, Ehrhardt AA, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Johnson MO, et al. Depressive symptomatology among HIV-positive women in the era of HAART: a stress and coping model. Am J Community Psychol. 2006;38(3–4):275–85. doi: 10.1007/s10464-006-9083-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson TE, Barron Y, Cohen M, Richardson J, Greenblatt R, Sacks HS, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and its association with sexual behavior in a national sample of women with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(4):529–34. doi: 10.1086/338397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalichman S, Rompa D. HIV treatment adherence and unprotected sex practices in people receiving antiretroviral therapy. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:59–61. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diamond C, Richardson JL, Milam J, Stoyanoff S, McCutchan JA, Kemper C, et al. Use of and adherence to antiretroviral therapy is associated with decreased sexual risk behavior in HIV clinic patients. J AIDS. 2005;39(2):211–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Remien RH, Exner TM, Morin SF, Ehrhardt AA, Johnson MO, Correale J, et al. Medication adherence and sexual risk behavior among HIV-infected adults: implications for transmission of resistant virus. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(5):663–75. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnell D, Baeten jM, Kiarie j, Thomas KK, Stevens W, Cohen CR, McIntyre J, Lingappa JR, Celum C. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:2092–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennett JA, Young HM, Nail LM, Winters-Stone K, Hanson G. A telephone-only motivational intervention to increase physical activity in rural adults: a randomized controlled trial. Nurs Res. 2008;57(1):24–32. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000280661.34502.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Resnicow K, Wallace DC, Jackson A, Digirolamo A, Odom E, Wang T, et al. Dietary change through African American churches: baseline results and program description of the eat for life trial. J Cancer Educ. 2000;15(3):156–63. doi: 10.1080/08858190009528685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith DE, Heckemeyer CM, Kratt PP, Mason DA. Motivational interviewing to improve adherence to a behavioral weight-control program for older obese women with NIDDM. A pilot study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(1):52–4. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein MD, Herman DS, Anderson BJ. A motivational intervention trial to reduce cocaine use. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36(1):118–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parsons JT, Golub SA, Rosof E, Holder C. Motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioral intervention to improve HIV medication adherence among hazardous drinkers: a randomized controlled trial. J AIDS. 2007;46(4):443–50. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e318158a461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velasquez MM, von Sternberg K, Johnson DH, Green C, Carbonari JP, Parsons JT. Reducing sexual risk behaviors and alcohol use among HIV-positive men who have sex with men: a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(4):657–67. doi: 10.1037/a0015519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiIorio C, McCarty F, Resnicow K, McDonnell Holstad M, Soet J, Yeager K, et al. Using motivational interviewing to promote adherence to antiretroviral medications: a randomized controlled study. AIDS Care. 2008;20(3):273–83. doi: 10.1080/09540120701593489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golin CE, Earp J, Tien HC, Stewart P, Porter C, Howie L. A 2-arm, randomized, controlled trial of a motivational interviewing-based intervention to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) among patients failing or initiating ART. J AIDS. 2006;42(1):42–51. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000219771.97303.0a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Cornman DH, Amico RK, Bryan A, Friedland GH. Clinician-delivered intervention during routine clinical care reduces unprotected sexual behavior among HIV-infected patients. J AIDS. 2006;41(1):44–52. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000192000.15777.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Callahan EJ, Flynn NM, Kuenneth CA, Enders SR. Strategies to reduce HIV risk behavior in HIV primary care clinics: brief provider messages and specialist intervention. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(5 Suppl):S48–57. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golin CE, Patel S, Tiller K, Quinlivan EB, Grodensky CA, Boland M. Start talking about risks: development of a motivational interviewing-based safer sex program for people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(5 Suppl):S72–83. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9256-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nollen C, Drainoni ML, Sharp V. Designing and delivering a prevention project within an HIV treatment setting: lessons learned from a specialist model. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(5 Suppl):S84–94. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rutledge SE. Single-session motivational enhancement counseling to support change toward reduction of HIV transmission by HIV positive persons. Arch Sex Behav. 2007;36(2):313–9. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ingersoll K, Wagner C. Motivational enhancement groups for the Virginia substance abuse treatment outcome evaluation (SATOE) model: theoretical background and clinical guidelines. Virginia Addiction Technology Transfer Center Virginia Commonwealth University/Medical College of Virginia; Richmond, VA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrison-Beedy D, Carey MP, Kowalski J, Tu X. Group-based HIV risk reduction intervention for adolescent girls: evidence of feasibility and efficacy. Res Nurs Health. 2005;28(1):3–15. doi: 10.1002/nur.20056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holstad MM, DiIorio C, Magowe MK. Motivating HIV positive women to adhere to antiretroviral therapy and risk reduction behavior: the KHARMA Project. Online J Issues Nurs. 2006;11(1):5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ebbert DW, Connors H. Standardized patient experiences: evaluation of clinical performance and nurse practitioner student satisfaction. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2004;25(1):12–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.CDC Revision of the CDC surveillance case definition for acuired immunodeficiency syndrome. MMWR. 1987;36(1S):82–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.CDC Core measures for HIV/STD risk behavior and prevention: Questionnaire-based measurement for surveys and other data systems. Sexual behavior questions version 5.00. 2001 5/27/ 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Metzger DS, Koblin B, Turner C, Navaline H, Valenti F, Holte S, et al. Randomized controlled trial of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing: utility and acceptability in longitudinal studies. HIVNET vaccine preparedness study protocol team. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(2):99–106. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams M, Bowen A, Ross M, Freeman R, Elwood W. Perceived compliance with AZT dosing among a sample of African-American drug users. Int J STD AIDS. 2000;11(1):57–63. doi: 10.1258/0956462001914797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones DL, McPherson-Baker S, Lydston D, Camille J, Brondolo E, Tobin JN, et al. Efficacy of a group medication adherence intervention among HIV positive women: the SMART/EST Women’s Project. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(1):79–86. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9165-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]