Abstract

Statistical approaches were employed for the optimization of different cultural parameters for the production of laccase by the white rot fungus Fomes fomentarius MUCL 35117 in wheat bran-based solid medium. first, screening of production parameters was performed using an asymmetrical design 2533//16, and the variables with statistically significant effects on laccase production were identified. Second, inoculum size, CaCl2 concentration, CuSO4 concentration, and incubation time were selected for further optimization studies using a Hoke design. The application of the response surface methodology allows us to determine a set of optimal conditions (CaCl2, 5.5 mg/gs, CuSO4, 2.5 mg/gs, inoculum size, 3 fungal discs (6 mm Ø), and 13 days of static cultivation). Experiments carried out under these conditions led to a laccase production yield of 150 U/g dry substrate.

1. Introduction

Laccases (benzenediol : oxygen oxidoreductases [EC 1.10.3.2]) are copper-containing enzymes catalyzing the oxidation of a broad number of phenolic compounds and aromatic amines by using molecular oxygen as the electron acceptor, which is reduced to water. Laccase can also oxidize nonphenolic substrates in the presence of appropriate redox mediators [1].

This group of enzymes has attracted increasing scientific attention in the recent years due to their application in several biotechnological processes. Such applications include the detoxification of industrial effluents, the use as a tool for medical diagnostics, and the use as a bioremediation agent to clean up herbicides, pesticides, and certain explosives in soil [2].

The application of these oxidative enzymes to biotechnological processes requires the production of high amounts of enzyme at low cost. In this context, solid state fermentation (SSF) appeared as an interesting alternative for the enzymes production [3]. SSF offers advantages over liquid cultivation, especially for the fungal cultures, as there is higher productivity per unit volume, reduced energy requirements, lower capital investment, low waste water output, higher concentrations of metabolites obtained, and low downstream processing cost [4].

The selection of an adequate support for performing SSF is essential, since the success of the process depends on it. Various agricultural substrates/byproducts such as banana waste, orange peelings, coconut flesh, chestnut shell, barley bran, and wheat bran have been successfully used in solid-state fermentation for laccase production by white-rot fungi [5–8].

Wheat bran, an abundant byproduct formed during wheat flour preparation, has been selected to perform the present study, because it has the physical integrity to serve as a supporting material and it provides the fungus, an environment similar to its natural habitat which is conducive for the high secretion of lignolytic enzymes. In addition, wheat bran is an abundant source for hydroxycinnamic acids, particularly ferulic and p-coumaric acids, which are known to stimulate laccase production [9]. Indeed, these hydroxycinnamic acids, covalently bound to cell wall polymers (pectins, arabinoxylans, and xyloglucans) through ester linkages, could be released after feruloyl esterase action as described in several white-rot fungi [10].

Production of laccase under SSF is affected by diverse typical fermentation factors such as moisture level, carbon and nitrogen source supplementation, and inoculum size [11–13]. Moreover, different compounds have also been widely used to stimulate laccase production. Among them, the effect of copper on laccase formation is outstanding [9, 14]. For effective laccase expression, it is highly essential to find the critical variables affecting laccase production yield and to establish the optimal set of experimental conditions for the whole solid-state culture process, which further facilitates economic design of the full-scale fermentation operation system.

Conventional optimization method is usually performed by varying the levels of one independent variable while fixing other variables at a certain level. This method is laborious and time consuming, and often interaction effects are overlooked [15]. Statistical experimental designs are powerful tools for searching the key factors rapidly from a multivariable system and to define the optimum settings of these factor levels. Asymmetrical screening design is one such method that has been used for screening multiple factors at a time, taking different level numbers [16–19]. This experimental design is particularly useful for initial screening, as it is used for the estimation of only the main effects. The significant factors obtained from the screening experiments could be further optimized by employing response surface methodology that enables the examination of the combinatory effect of the retained factors and the determination of their optimal levels [20–25]. The application of statistical experimental design techniques in fermentation process development can result in improved product yields, reduced process variability, closer confirmation of the output response to nominal and target requirements, and reduced development time and overall costs [26, 27]. Successful application of RSM to enhance enzyme production in SSF by optimizing the culture media has been reported [28–31]. On the other hand, studies regarding optimization of solid culture medium for the production of laccase are still few in the scientific literature [32].

In this work, laccase production by the white rot fungus F. fomentarius in wheat bran-based solid medium has been optimized using experimental designs [19–25]. In a first step, a screening of the most important factors is carried out with an asymmetrical design 2533//16. In a second step, Hoke design is applied to determine response surfaces as a function of some of the significant parameters and then to choose the optimal solid state conditions for laccase production.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganism

Fomes fomentarius (MUCL 35117) used in this study was obtained from the Belgian Coordinated Collections of Microorganisms/Mycothèque de l'Université Catholique de Louvain (BCCM/MUCL) and maintained at 4°C on 2% malt extract agar (MEA). This strain was maintained on 2% malt extract agar (MEA) slants at 4°C and subcultured every three months.

2.2. Solid Medium Preparation

Wheat bran purchased from a local market was employed as support substrate for SSF. The average particle size of the wheat bran was 1–5 mm. The chemical composition of this substrate was hemicelluloses (notably arabinoxylans, ca. 30%), cellulose (10–15%), starch (10–20%), proteins (15–22%), lignin (4–8%), and other minor components such as cutin and lipids [33, 34].

The experiments were performed in 125-mL flasks with 2.5 g of wheat bran moistened with the required volume of buffer (sodium acetate or citrate phosphate buffer 20 mM, pH 5) containing various nutritional factors according to the experimental designs shown in Tables 1 and 2. The medium was sterilized at 121°C for 20 min. After cooling, the substrate was inoculated with mycelial discs (each 6 mm diameter) obtained from the periphery of 7 days fungal culture grown on MEA plates. The contents were incubated statically in complete darkness at 30°C.

Table 1.

Experimental conditions of the asymmetrical screening design.

| Levels | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| M/S ratio (ml/gs) (A) | 3 | 6 | — |

| MgSO4 (mg/gs) (B) | 0.3 | 3 | — |

| CaCl2 (mg/gs) (C) | 0.3 | 3 | — |

| Moisturizing agent* (D) | Sodium acetate buffer (SAB) |

Citrate phosphate buffer (CPB) |

— |

| Inoculum size (discs**) (E) | 4 | 8 | — |

| Glucose (mg/gs) (F) | 0 | 30 | 60 |

| Ammonium tartrate (mg/gs) (G) | 0 | 5.5 | 11 |

| CuSO4 (ml/gs) (H) | 0 | 0.75 | 1.5 |

*20 mM, pH 5; **diameter, 6 mm.

Table 2.

Experimental conditions of the screening design and the corresponding responses.

| Run no. |

M/S ratio (ml/gs) |

MgSO4 (mg/gs) |

CaCl2 (mg/gs) |

Moisturizing —agent |

Inoculum size (discs) |

Glucose (mg/gs) |

Ammonium tartrate (mg/gs) |

CuSO4 (mg/gs) |

Measured and estimated laccase activities (U/gds) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 days |

7 days |

10 days |

13 days |

16 days |

|||||||||

| 1 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | CPB | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.16 1.88 |

37.00 38.68 |

2.88 9.93 |

10.00 9.54 |

6.60 10.26 |

| 2 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | SAB | 4 | 30 | 5.5 | 0.75 | 2.74 2.65 |

19.62 20.09 |

1.56 −0.04 |

1.56 1.37 |

0.52 −0.41 |

| 3 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | CPB | 8 | 60 | 11 | 1.5 | 2.74 2.65 |

39.92 40.39 |

13.60 11.99 |

17.04 16.85 |

5.30 4.37 |

| 4 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | SAB | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.66 4.12 |

45.16 42.52 |

9.16 5.31 |

3.78 4.62 |

3.46 1.66 |

| 5 | 6 | 0.3 | 3 | CPB | 4 | 30 | 11 | 0 | 3.60 3.92 |

61.52 58.14 |

63.48 63.38 |

74.60 73.93 |

85.08 81.99 |

| 6 | 6 | 0.3 | 3 | SAB | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | 4.70 5.04 |

63.48 61.83 |

69.38 78.32 |

96.86 93.51 |

108.64 107.09 |

| 7 | 6 | 0.3 | 3 | CPB | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0.75 | 6.60 6.08 |

64.14 66.74 |

103.40 91.25 |

81.16 84.12 |

101.44 101.13 |

| 8 | 6 | 0.3 | 3 | SAB | 8 | 60 | 5.5 | 0 | 5.16 5.02 |

57.60 60.02 |

61.52 64.82 |

67.40 68.45 |

65.44 70.38 |

| 9 | 3 | 3 | 3 | CPB | 4 | 60 | 0 | 0.75 | 1.50 1.88 |

36.00 34.83 |

7.98 12.98 |

2.34 1.70 |

2.02 3.28 |

| 10 | 3 | 3 | 3 | SAB | 4 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 3.26 2.80 |

37.96 42.77 |

15.96 8.91 |

7.46 10.46 |

0.26 4.29 |

| 11 | 3 | 3 | 3 | CPB | 8 | 0 | 5.5 | 0 | 4.50 4.78 |

51.70 47.84 |

15.44 19.28 |

9.42 6.04 |

9.28 3.39 |

| 12 | 3 | 3 | 3 | SAB | 8 | 30 | 0 | 1.5 | 6.40 6.20 |

40.58 40.80 |

1.56 −0.24 |

1.30 2.31 |

2.16 2.76 |

| 13 | 6 | 3 | 0.3 | CPB | 4 | 0 | 5.5 | 1.5 | 4.90 4.85 |

56.94 57.90 |

99.48 93.93 |

87.70 90.22 |

92.28 94.16 |

| 14 | 6 | 3 | 0.3 | SAB | 4 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 3.60 3.45 |

55.62 53.89 |

70.68 63.98 |

61.52 61.30 |

66.76 61.49 |

| 15 | 6 | 3 | 0.3 | CPB | 8 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 6.60 6.57 |

58.24 60.92 |

64.80 68.30 |

57.60 57.44 |

60.20 63.61 |

| 16 | 6 | 3 | 0.3 | SAB | 8 | 0 | 11 | 0.75 | 5.94 6.17 |

63.48 61.57 |

83.12 91.87 |

82.46 80.32 |

80.50 80.48 |

2.3. Enzyme Extraction

The enzyme was extracted with sodium acetate or citrate-phosphate buffer 20 mM, pH 5 (20 mL buffer/g substrate) by shaking for 1 h at 160 rpm at room temperature. The suspension was filtered and centrifuged at 4°C, 8,000 g for 20 min, and the supernatant was used in enzyme assays.

2.4. Enzyme Assays

The laccase activity was measured by monitoring the oxidation of 5 mM 2,6-dimethoxyphenol (DMP) buffered with 0.1 M tartrate buffer (pH 4.5) at 469 nm for 1 min [35]. To calculate the enzyme activity, an absorption coefficient of 27,500 M−1 cm−1 was used. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to oxidize 1 μM of DMP per minute.

2.5. Asymmetrical Design and Hoke Design

The optimization of laccase production yield in solid-state medium has been carried out in two steps as described below.

2.5.1. Screening of Important Cultural Factors Using Asymmetrical Design

For systems with a great number of variables, different approaches of experimental factorial designs can be applied to achieve a screening of critical variables and to estimate their main effects on the responses [16, 19, 24].

In this study, a 2533//16 experimental design was used to find out the critical medium components for laccase production by F. fomentarius under SSF. It allows the investigation of eight factors in sixteen experiments, five factors A–E each at two levels and three factors F–H each at three levels. Table 1 lists the values given to each factor, the choice was based on previous literature works [5, 11–13] and preliminary experiments. Table 2 shows the 2533//16 experimental design.

From the 16 runs, we can compute, using the least square method [19–24], the ‘‘weight” of each factor level. For each factor, the weight of each level is related to the upper level weight, which becomes the ‘‘reference state” among each factor [24]. The weight describes the factor effects on the response when changing factor levels with respect to the reference state. The weight of glucose amount (factor F) when fixed at level 1 (F1), for example, corresponds to the differential effect of glucose amount on the response when changing its value from level 3 (60 mg/g) to level 1 (0 mg/g). The obtained results are generally presented as histograms, which graphically illustrate the variable differential weights [24]. At the end of this first step, the variables that did not have a significant effect (checked by applying a t-test) on the responses are screened out; the remaining factors affecting the responses are further optimized.

2.5.2. Optimization of Selected Factors Using Response Surface Methodology

The screening data revealed four factors (CaCl2 concentration, inoculum size, CuSO4 concentration and incubation time) influencing the SSF production of laccase by F. fomentarius. Optimization of laccase production yield was achieved by using the response surface methodology (RSM). This approach explores the response surfaces covered in the experimental design, thus making the optimization process more efficient and effective [20–23].

The most frequent designs in optimization problems involving three or more factors are central composite designs, Box-Behnken designs, D-optimal designs, and others, such as Hoke designs. [20–25, 36] Central composite designs and Box-Behnken designs are the most appropriate to detect curvatures in a multidimensional space but require a large number of experiments beyond three factors. D-optimal designs are less frequent, but adequate in cases involving linear functions where the factors can only be varied over a restricted area, and thereby creates an irregular experimental domain in which orthogonality cannot be achieved. Hoke designs are economical second-order designs [36] based on irregular fractions of partially balanced type of the 3k factorial for a number of factors k ≥ 3. They require fewer experiments than the central composite designs and Box-Behnken designs.

In this work, we consider that the experimental region is a hypercube, thus, to define the optimum settings of the four active factor levels; we applied a four-factor Hoke D6 design [36] in the experimental domain presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Experimental domain for the Hoke design.

| Variable | Factor | Unit | Center | Step of variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | CaCl2 | mg/gs | 3.0 | 2.5 |

| X2 | Inoculum size | discs | 6.0 | 3.0 |

| X3 | CuSO4 | mg/gs | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| X4 | Incubation time | days | 10 | 6 |

The response (laccase yield) can be described by the following second-order model adequate for predicting the responses in the experimental region:

| (1) |

where, η: the theoretical response function, Xj: coded variables of the system, β0, βj, βjk, and βjj: true model coefficients.

The observed response yi for the ith experiment is

| (2) |

The model coefficients β0, βj,…, and βjj are estimated by a least squares fitting of the model to the experimental results obtained in the 23 design points of the four-variable Hoke D6 design (Table 4). For the estimated values of these coefficients, the symbols b0, bj,…, and bjj will be used. The computed values of the responses are designated by

Table 4.

Experimental conditions of the Hoke design and the corresponding responses.

| Run no. |

X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | CaCl2 (mg/gds) |

Inoculum size (Discs*) |

CuSO4 (mg/gds) |

Incubation time (days) |

Measured and estimated laccase activities (U/gds) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −1.00000 | −1.00000 | −1.00000 | −1.00000 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.5 | 4 | 6.72 | 5.02 |

| 2 | −1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.5 | 6 | 1.5 | 10 | 121.00 | 119.93 |

| 3 | 0.00000 | −1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 3.0 | 3 | 1.5 | 10 | 115.90 | 122.34 |

| 4 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | −1.00000 | 0.00000 | 3.0 | 6 | 0.5 | 10 | 101.12 | 110.96 |

| 5 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | −1.00000 | 3.0 | 6 | 1.5 | 4 | 8.56 | 5.49 |

| 6 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | −1.00000 | 5.5 | 9 | 2.5 | 4 | 11.60 | 14.77 |

| 7 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | −1.00000 | 1.00000 | 5.5 | 9 | 0.5 | 16 | 89.32 | 86.04 |

| 8 | 1.00000 | −1.00000 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | 5.5 | 3 | 2.5 | 16 | 138.24 | 136.66 |

| 9 | −1.00000 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | 0.5 | 9 | 2.5 | 16 | 103.90 | 106.07 |

| 10 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | −1.00000 | −1.00000 | 5.5 | 9 | 0.5 | 4 | 12.50 | 11.84 |

| 11 | 1.00000 | −1.00000 | 1.00000 | −1.00000 | 5.5 | 3 | 2.5 | 4 | 6.28 | 6.47 |

| 12 | 1.00000 | −1.00000 | −1.00000 | 1.00000 | 5.5 | 3 | 0.5 | 16 | 104.16 | 101.12 |

| 13 | −1.00000 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | −1.00000 | 0.5 | 9 | 2.5 | 4 | 8.42 | 10.48 |

| 14 | −1.00000 | 1.00000 | −1.00000 | 1.00000 | 0.5 | 9 | 0.5 | 16 | 80.12 | 78.96 |

| 15 | −1.00000 | −1.00000 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | 0.5 | 3 | 2.5 | 16 | 121.84 | 121.53 |

| 16 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 5.5 | 9 | 2.5 | 10 | 139.20 | 133.46 |

| 17 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 1.00000 | 5.5 | 9 | 1.5 | 16 | 97.26 | 104.42 |

| 18 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | 5.5 | 6 | 2.5 | 16 | 123.88 | 127.65 |

| 19 | 0.00000 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | 3.0 | 9 | 2.5 | 16 | 113.96 | 110.22 |

| 20 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 3.0 | 6 | 1.5 | 10 | 128.18 | 119.84 |

| 21 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 3.0 | 6 | 1.5 | 10 | 120.36 | 119.84 |

| 22 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 3.0 | 6 | 1.5 | 10 | 117.46 | 119.84 |

| 23 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 3.0 | 6 | 1.5 | 10 | 122.82 | 119.84 |

| 24 | −0.39528 | −0.22822 | −0.16137 | 0.00000 | 2.0 | 5 | 1.3 | 10 | 122.28 | 118.35 |

| 25 | 0.39528 | −0.22822 | −0.16137 | 0.00000 | 4.0 | 5 | 1.3 | 10 | 120.42 | 120.51 |

| 26 | 0.00000 | 0.45644 | −0.16137 | 0.00000 | 3.0 | 7 | 1.3 | 10 | 113.70 | 118.07 |

| 27 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.48412 | 0.00000 | 3.0 | 6 | 2.0 | 10 | 129.30 | 123.33 |

| 28 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.50000 | 3.0 | 6 | 1.5 | 13 | 125.42 | 127.66 |

* diameter, 6 mm.

| (3) |

The four replicates at the center point (runs n° 20 to 23) are carried out in order to estimate the pure error variance [22–24]. A statistical test of the model fit is made by comparing the variance due to the lack of fit to the pure error variance using the F-test. The fitted model is considered adequate if the variance due to the lack of fit is not significantly different from the pure error variance [22–24]. The adequacy of the model is further tested using four check points [24, 25]. The fitted model was used to study the relative sensitivity of the responses to the variables in the whole domain and to look for the optimal experimental conditions. In this paper, the canonical analysis is used to find out the best experimental conditions, which permitted the maximization of the laccase production yield. It consists of rewriting the fitted second-degree equation in a form in which it can be more readily understood. This is accomplished by a rotation of axes that remove all cross-product terms bjkXjXk while keeping the initial origin at the centre point. This step is suitable when the stationary point is outside of the experimental domain [37]. The relationship between the response and the experimental variables is illustrated graphically by plotting the response surfaces and the isoresponse curves [23, 24].

In this study, the generation and the data treatment of the 2533//16 screening design and the Hoke design are performed using the experimental design software NemrodW [38].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Screening Design

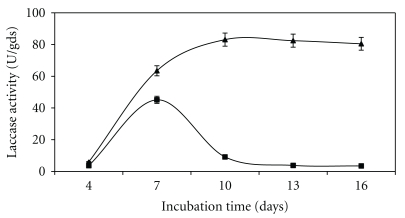

A total of eight variables were analyzed for their effect on laccase production yield using an asymmetrical screening design. Sixteen experiments have been carried out according to the SSF medium preparation method described above and the conditions fixed by the experimental design (Table 2). The obtained responses values related to laccase yields obtained in 4, 7, 10, 13, and 16 days of fungal cultivation are reported in Table 2. As shown in this table, for low moisture to substrate ratios (M/S = 3 : 1 v/w) (experiments N° 1–4 and 9–12), the laccase production increases until 7 days of cultivation, and then, a notable decrease of the enzymatic activity was observed (Figure 1). This result is probably due to reduced solubility of nutrients from the solid substrate, low substrate swelling, and high water tension [39, 40]. On the conterary, for the experiments conducted with high moisture to substrate ratios (M/S = 6 : 1 v/w) (experiments N° 5–8 and 13–16), laccase production exhibited a gradual increase, followed by a stabilization phase, where maximal enzyme production was recorded (Figure 1). This stability could likely be due to the cultures are better aerated and clogging problems are avoided [8]. Thus, we chose to estimate the effect of the eight variables on laccase yields obtained in 7 and 16 days of fungal cultivation.

Figure 1.

Evolution of laccase production by F. fomentarius grown on wheat bran-based solid medium (■) with low moisture to substrate ratio (M/S = 3 : 1 v/w) and (▲) with high moisture to substrate ratio (M/S = 6 : 1 v/w).

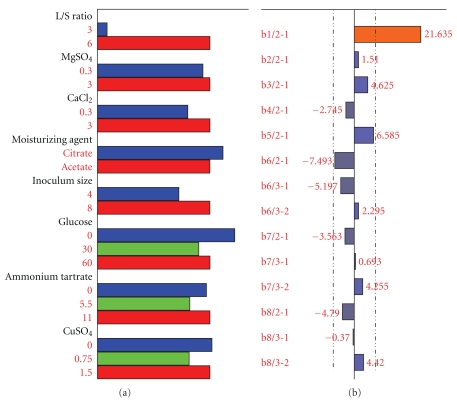

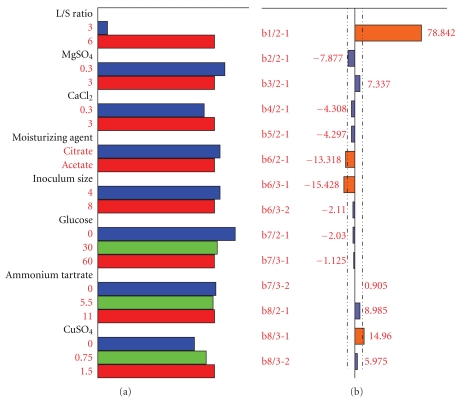

In Table 5 we report coefficient values (the weight associated to each factor level) calculated, as described above, and statistical analyses using t-test. These results are illustrated by the histograms shown in Figures 2 and 3, which represent the differential effects of each factor when considering two different levels taken two by two. b6/2-1, for example, defines the weight of factor F (glucose) on the response when changing its level from 1 to 2.

Table 5.

Estimates of and statistics on the coefficients.

| Name | Coefficient | F. inflation | Standard deviation |

t exp. | Significance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laccase yield on 7th day of fermentation (U/gds) | |||||

| b0 | 65.420 | 4.622 | 14.15 | 0.0145*** | |

| b1A | −21.635 | 1.00 | 2.387 | −9.06 | 0.0821*** |

| b2A | −1.510 | 1.00 | 2.387 | −0.63 | 56.1 |

| b3A | −4.625 | 1.00 | 2.387 | −1.94 | 12.5 |

| b4A | 2.745 | 1.00 | 2.387 | 1.15 | 31.4 |

| b5A | −6.585 | 1.00 | 2.387 | −2.76 | 5.1 |

| b6A | 5.197 | 1.50 | 2.923 | 1.78 | 15.0 |

| b6B | −2.295 | 1.50 | 3.375 | −0.68 | 53.4 |

| b7A | −0.693 | 1.50 | 2.923 | −0.24 | 82.4 |

| b7B | −4.255 | 1.50 | 3.375 | −1.26 | 27.6 |

| b8A | 0.370 | 1.50 | 2.923 | 0.13 | 90.5 |

| b8B | −4.420 | 1.50 | 3.375 | −1.31 | 26.1 |

| Laccase yield on 16th day of fermentation (U/gds) | |||||

| b0 | 78.366 | 5.939 | 13.20 | 0.0191*** | |

| b1A | −78.842 | 1.00 | 3.067 | −25.71 | <0.01*** |

| b2A | 7.877 | 1.00 | 3.067 | 2.57 | 6.2 |

| b3A | −7.337 | 1.00 | 3.067 | −2.39 | 7.5 |

| b4A | 4.308 | 1.00 | 3.067 | 1.40 | 23.3 |

| b5A | 4.297 | 1.00 | 3.067 | 1.40 | 23.4 |

| b6A | 15.428 | 1.50 | 3.756 | 4.11 | 1.48* |

| b6B | 2.110 | 1.50 | 4.337 | 0.49 | 65.2 |

| b7A | 1.125 | 1.50 | 3.756 | 0.30 | 77.9 |

| b7B | −0.905 | 1.50 | 4.337 | −0.21 | 84.5 |

| b8A | −14.960 | 1.50 | 3.756 | −3.98 | 1.64* |

| b8B | −5.975 | 1.50 | 4.337 | −1.38 | 24.0 |

*Significant at the level 95%; **significant at the level 99%; ***significant at the level 99.9%.

Figure 2.

Graphical study of the effects of different operational variables on laccase production at 7 days days of cultivation. (a) Graphical study of the total effects and (b) Differences of the weights of the different levels.

Figure 3.

Graphical study of the effects of different operational variables on laccase production at 16 days days of cultivation. (a) Graphical study of the total effects and (b) Differences of the weights of the different levels.

As shown in Table 5 and Figures 2 and 3, moisture to substrate ratio (A) exhibits stronger influence on the laccase production compared to other factors. For SSF, moisture content is a key parameter to control the growth of microorganism and metabolite production [40–42]. In this work, the highest laccase yields were observed for moisture to substrate ratio (v/w) of 6 : 1. A similar effect of moisture to substrate ratio on laccase production, by Trametes hirsuta grown on crushed orange peelings, was reported by Rosales et al. [8]. Supplementary experiments, conducted using higher M/S ratios, lead to a very low laccase yields (data not shown). Consequently, we fixed the ratio M/S at 6 : 1 v/w in the optimization step of this study.

MgSO4 concentration (B), CaCl2 concentration (C) moisturizing agent (D), inoculum size (E), and ammonium tartrate concentration (G) seem to have no significant effect on the response. However, we choose to include the factors C and E in the optimization design for two reasons. First, CaCl2 concentration and inoculum size have a relatively high positive effect on the response (Figure 2). Second, the role of calcium in the maintenance of the protein structures and the stabilization of the activities of several enzymes has been well documented [43, 44]. In the same way, many reports have been given about the effect of inoculum size in fungal growth and productivity [40, 41, 45]. Too high or low inoculum concentration cause low growth and productivity. When the inoculum size is small, longer cultivation time is required. A large inoculum size in culture will lead rapidly to crowded and nutritional deficiency. A mycelium mat will soon cover the culture medium causing poor substrate aeration [40].

Table 5 and Figures 2 and 3 show that glucose (F) as carbon supplement exhibits a negative effect on the response. The production is raised more in absence of glucose that with 30 or 60 mg of glucose/g substrate. Such inhibitory effect of glucose on laccase production has also been described by Galhaup et al. [46].

We already mentioned that the ammonium tartrate concentration has no significant effect on the response. Consequently, it can be used at its low level (0%). Thus, the addition of this nitrogen source is not required.

We can then conclude that wheat bran could be employed without adding any initial amount of carbon and nitrogen supplements in the culture medium. This will help to suppress the overall production cost of culture medium. During cultivation on wheat bran, water soluble cellulose and hemicellulose fractions could serve as carbon source which leads to a carbon: nitrogen ratio sufficient for an effective laccase induction [47, 48].

Finally, the increase in cupper sulphate concentrations (H) (0.75 to 1.5 mg/gds) has resulted in higher laccase production especially at 16 days of cultivation (Figure 3). Many studies have shown that laccase yields in several white-rot species were significantly increased in media containing high concentrations of CuSO4 [46, 49–52].

Results of the screening design pave the way for the next step of the research.

3.2. Hoke D6 Design

Based on the results of asymmetrical design experiments, some factors are fixed at their best levels: A2 B1 D1 F1 G1. In order to look for optimal experimental conditions, a second-order model is built to analyse the relation between the four factors (CaCl2, inoculum size, CuSO4, and incubation time) and the response (laccase yield). Table 4 shows the coded and the real experimental conditions of the Hoke design with the corresponding observed values of the studied response. Results of experiments of the Hoke design are used to estimate the model coefficients (without using the check points). The resulting estimated model, expressed in coded variables is

| (4) |

3.2.1. Statistical Analysis and Validation of the Model

The analysis of variance for the fitted model (Table 6) shows that the regression sum of squares is statistically significant (their P value is less than .05) and the lack of fit is not significant [20–25]. Thus, we can conclude that the models correlate well with the measured data.

Table 6.

Analysis of variance of the Hoke design response.

| Source of variation | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | Ratio |

P-value (significance) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 52728.2 | 14 | 3766.30 | 76.8852 | <.0001 (***) |

| Residuals | 391.889 | 8 | 48.9861 | ||

| Lack of fit | 329.891 | 5 | 65.9781 | 3.1926 | 0.184 (N.S.) |

| Error | 61.9979 | 3 | 20.6660 | ||

| Total | 53120.1 | 22 | |||

***significant at the level 99.9%, N.S.: Non significant at the level 95%.

In addition, Table 7 shows the check point results used to validate the accuracy of the model. The measured values are very close to those calculated using the model equations. Indeed, the differences between calculated and measured responses are not statistically significant when using the t-test as shown in Table 7. We can then conclude that the second-order models are adequate to describe the response surfaces and can be used as prediction equation in the studied domain.

Table 7.

The numerical results for check points.

| Run | Yexp | Ycalc | Yexp − Ycalc | dU | Ecart type |

df | t exp. | Signif % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 122.280 | 118.348 | 3.932 | 0.162 | 7.545 | 8 | 0.521 | 61.6 |

| 25 | 120.420 | 120.512 | −0.092 | 0.194 | 7.647 | 8 | −0.012 | 99.1 |

| 26 | 113.700 | 118.074 | −4.374 | 0.201 | 7.671 | 8 | −0.570 | 58.4 |

| 27 | 129.300 | 123.333 | 5.967 | 0.204 | 7.680 | 8 | 0.777 | 46.0 |

| 28 | 125.420 | 127.661 | −2.241 | 0.209 | 7.695 | 8 | −0.291 | 77.8 |

3.2.2. Interpretation of the Response Surface Model

The second-order polynomial model is a conic function, and it can be analyzed by canonical analysis. This function has a stationary point S, where the partial derivative of predicted response with respect to each of the variables is zero (∂y/∂X1 = 0; ∂y/∂X2 = 0; ∂y/∂X3 = 0; ∂y/∂X4 = 0). This point could be a maximum, a minimum, or a saddle point.

In the present study, the coordinates of the saddle point S are X1 = −2.032; X2 = 9.876; X3 = 5.419, and X4 = 0.205. It corresponds to a maximum of . This point is situated outside the experimental domain. In this case, the canonical analysis requires only a rotation of the Xj axes in such a way that they become parallel to the principal axes Zj of the contour system. Under these conditions, the canonical model is of the form

| (5) |

The λj (j = 1,2, 3,4) will describe the curvature of the response, while the linear coefficient bj will describe the slope of the ridge in the corresponding direction. The constant ys is the calculated response value at the stationary point. The interpretation is easier by analyzing each the response along every Zj-axis separately. Using the variable transformation equations:

| (6) |

we obtained the following canonical form of the model:

| (7) |

These data allow us to determine the features of the response surface in each direction of the experimental domain. When analyzing the response surface along each of the four directions OZ1, OZ2, OZ3, and OZ4, the equation of the response is reduced to the following equations, respectively:

| (8) |

The corresponding curves are represented in Figure 4. From these curves and the variable transformation equations, we can conclude that the maximization of the laccase yield requires high level of X1 (X1 = 1), low level of X2 (X2 = −1), high level of X3 (X3 = 1), and the relatively high level of X4 (X4 = 0.5). This corresponds to the following settings of the natural variables: CaCl2 = 5.5 mg/gds, inoculum size =3 discs, CuSO4 = 2.5 mg/gds and incubation time = 13 days.

Figure 4.

Curvature of laccase yield response versus Zj (j = 1,2, 3 and 4).

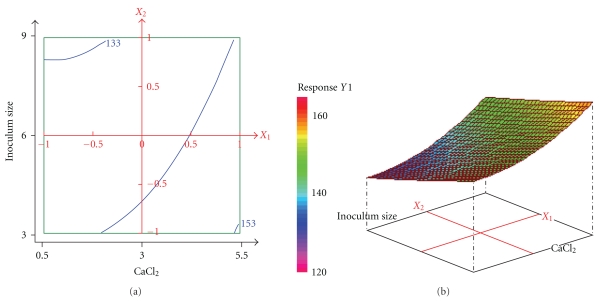

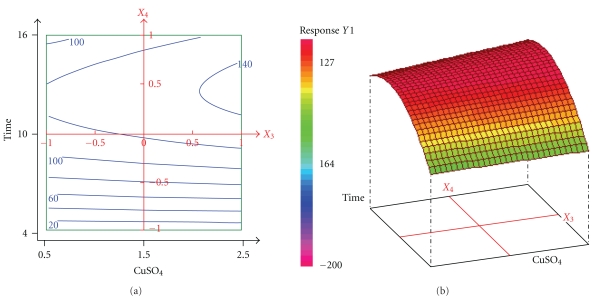

Figures 5 and 6 illustrate graphically the evolution of the laccase yield versus two variables, while the other two variables were held constant.

Figure 5.

Contour plot and response surface plot showing the effect of CaCl2 and inoculum size on the laccase yield with incubation time, CuSO4 fixed, respectively, at 13 days and 2.5 mg/gs. Laccase activity is expressed in U/gds.

Figure 6.

Contour plot and response surface plot showing the effect of incubation time, CuSO4, on the laccase yield with CaCl2 and inoculum size fixed respectively at 3.0 mg/gs and 3 discs. Laccase activity is expressed in U/gds.

Figure 5 shows that with incubation time of 13 days and CuSO4 concentration of 2.5 mg/gs, the laccase yield can be enhanced from 130 to 150 U/gs by the increase of the concentration of CaCl2 and the decrease of the inoculum size. As reported by many researchers [53–56], an increase of the inoculum size ensures a rapid proliferation of biomass and enzyme synthesis. However, after a certain limit, the enzyme production could decrease because of the depletion of nutrients, which results in decrease in metabolic activity.

From Figure 6, we have observed that the enzyme yield enhances essentially by increasing the incubation time. However, extended cultivation time may cause inhibition of enzyme synthesis. This fact was also reported by other investigators during other laccase production studies [57, 58]. It is also clear from Figure 6 that there is a gradual increase in the enzyme yields upon increasing the concentration of copper sulphate. Thus, it was implied that a high concentration of copper sulphate (2.5 mg/gs) was favourable for the production of laccase by F. fomentarius. These results were in agreement with others, for example, Couto and Sanromán [6], who reported an increase in laccase activity by almost 3-fold by adding 2 mM copper sulphate to solid state cultures of Trametes hirsuta. Many studies have shown that laccase mRNA levels in several white-rot species were significantly increased in media containing high concentrations of cupric ions [49–51]. Multiple putative cis-acting elements, termed metal responsive elements, were identified in the promoter region of several laccase genes that are transcriptionally activated by copper [51, 52]. A possible explanation for this stimulatory effect of copper on laccase biosynthesis could be a role for this enzyme activity in melanin synthesis [59].

3.2.3. Optimization

As the results of the canonical analysis agree with those of the contour plot study, we can conclude that there is no a masked optimum: the one predicted by few sections of contour plot analysis represents a real optimum for the whole experimental domain. The NemrodW sofware predicted the maximum laccase yield to be 153.3 ± 11.5 U/gds in optimized conditions (CaCl2, 5.5 mg/gs; CuSO4, 2.5 mg/gs; inoculum size, 3 fungal discs (6 mm Ø), and incubation time, 13 days). A supplementary experiment was carried out under the selected optimal conditions. It led to an experimental yield of laccase equal to 151.1 ± 6.0 U/gds which is very close to the expected value (153.3 U/gds). The optimized yield of laccase obtained in this work was higher than those obtained by other high laccase producer fungi; for example, some of the highest records of laccase production in SSF were obtained by Coriolus rigida (108 U/gs) [5], Trametes hirsuta (68.4 U/gs) [60], and Pleurotus ostreatus (65.4 U/gs) [13].

4. Conclusion

Statistical optimization of solid state fermentation conditions to obtain a high laccase yield by the white-rot fungus Fomes fomentarius has been successfully carried out using asymmetrical and Hoke designs. The optimal conditions for the production of laccase were determined as follows: CaCl2, 5.5 mg/gs, CuSO4, 2.5 mg/gs, inoculum size, 3 fungal discs (6 mm Ø), and incubation time, 13 days. Under these conditions, the experimental yield of laccase was 151.1 U/gds. The strategy adopted in this study was proved to be useful and powerful tool for screening, optimization, and modelling of solid-state fermentation process. Enhanced production of F. fomentarius laccase by using the statistical methodology outlined in this paper will help in various biotechnological applications at industrial levels.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to LPRAI—Marseille Company for the supply of the software package Nemrod W. M. Neifar and A. Kamoun have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Riva S. Laccases: blue enzymes for green chemistry. Trends in Biotechnology. 2006;24(5):219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodríguez Couto S, Toca Herrera JL. Industrial and biotechnological applications of laccases: a review. Biotechnology Advances. 2006;24(5):500–513. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodríguez Couto S, Sanromán MAA. Application of solid-state fermentation to ligninolytic enzyme production. Biochemical Engineering Journal. 2005;22(3):211–219. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hölker U, Höfer M, Lenz J. Biotechnological advantages of laboratory-scale solid-state fermentation with fungi. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2004;64(2):175–186. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1504-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gómez J, Pazos M, Couto SR, Sanromán MA. Chestnut shell and barley bran as potential substrates for laccase production by Coriolopsis rigida under solid-state conditions. Journal of Food Engineering. 2005;68(3):315–319. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Couto SR, Sanromán MA. Coconut flesh: a novel raw material for laccase production by Trametes hirsuta under solid-state conditions.: application to Lissamine Green B decolourization. Journal of Food Engineering. 2005;71(2):208–213. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osma JF, Toca Herrera JL, Rodríguez Couto S. Banana skin: a novel waste for laccase production by Trametes pubescens under solid-state conditions. Application to synthetic dye decolouration. Dyes and Pigments. 2007;75(1):32–37. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosales E, Rodríguez Couto S, Sanromán MAA. Increased laccase production by Trametes hirsuta grown on ground orange peelings. Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 2007;40(5):1286–1290. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neifar M, Jaouani A, Ellouze-Ghorbel R, Ellouze-Chaabouni S, Penninckx MJ. Effect of culturing processes and copper addition on laccase production by the white-rot fungus Fomes fomentarius MUCL 35117. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 2009;49(1):73–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2009.02621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dinis MJ, Bezerra RMF, Nunes F, et al. Modification of wheat straw lignin by solid state fermentation with white-rot fungi. Bioresource Technology. 2009;100(20):4829–4835. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu J, Duvnjak Z. The production of a laccase and the decrease of the phenolic content in canola meal during the growth of the fungus Pleurotus ostreatus in solid state fermentation processes. Engineering in Life Sciences. 2004;4(1):50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stajić M, Persky L, Friesem D, et al. Effect of different carbon and nitrogen sources on laccase and peroxidases production by selected Pleurotus species. Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 2006;38(1-2):65–73. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mishra A, Kumar S. Cyanobacterial biomass as N-supplement to agro-waste for hyper-production of laccase from Pleurotus ostreatus in solid state fermentation. Process Biochemistry. 2007;42(4):681–685. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gnanamani A, Jayaprakashvel M, Arulmani M, Sadulla S. Effect of inducers and culturing processes on laccase synthesis in Phanerochaete chrysosporium NCIM 1197 and the constitutive expression of laccase isozymes. Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 2006;38(7):1017–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beg QK, Sahai V, Gupta R. Statistical media optimization and alkaline protease production from Bacillus mojavensis in a bioreactor. Process Biochemistry. 2003;39(2):203–209. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathieu D, Phan-Tan-Luu R. Plans d’expériences: Application à l’entreprise. Paris, France: Technip; 1997. Approche méthodologique des surfaces de réponse; pp. 211–278. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phan-tan-luu R, Cela R. Comprehensive Chemometrics. chapter 1.09. New York, NY, USA: Elsevier; 2009. Experimental design: introduction. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baati R, Kamoun A, Chaabouni M, Sergent M, Phan-Tan-Luu R. Screening and optimization of the factors of a detergent admixture preparation. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems. 2006;80(2):198–208. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cela R, Claeys-Bruno M, Phan-Tan-Luu R. Comprehensive Chemometrics. Chapter 1.10. New York, NY, USA: Elsevier; 2009. Screening strategies. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Box EP, Hunter WG, Hunter JS. Statistics for Experimenters. New York, NY, USA: Wiley; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlson R. Design and Optimization in Organic Synthesis. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myers RH, Montgomery DC. Response Surface Methodology: Process and Product Optimization Using Designed Experiments. New York, NY, USA: Wiley; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goupy J. Plans d’Expériences Pour Surfaces de Response. Paris, France: Dunod; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis GA, Mathieu D, Phan-Tan-Luu R. Pharmaceutical Experimental Design. New York, NY, USA: Marcel Dekker; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarabia LA, Ortiz MC. Comprehensive Chemometrics. chapter 1.12. New York, NY, USA: Elsevier; 2009. Response surface methodology. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vohra A, Satyanarayana T. Statistical optimization of the medium components by response surface methodology to enhance phytase production by Pichia anomala. Process Biochemistry. 2002;37(9):999–1004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elibol M. Optimization of medium composition for actinorhodin production by Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) with response surface methodology. Process Biochemistry. 2004;39(9):1057–1062. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Francis F, Sabu A, Nampoothiri KM, et al. Use of response surface methodology for optimizing process parameters for the production of α-amylase by Aspergillus oryzae. Biochemical Engineering Journal. 2003;15(2):107–115. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Senthilkumar SR, Ashokkumar B, Chandra Raj K, Gunasekaran P. Optimization of medium composition for alkali-stable xylanase production by Aspergillus fischeri Fxn 1 in solid-state fermentation using central composite rotary design. Bioresource Technology. 2005;96(12):1380–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazutti M, Bender JP, Treichel H, Luccio MD. Optimization of inulinase production by solid-state fermentation using sugarcane bagasse as substrate. Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 2006;39(1):56–59. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Latifian M, Hamidi-Esfahani Z, Barzegar M. Evaluation of culture conditions for cellulase production by two Trichoderma reesei mutants under solid-state fermentation conditions. Bioresource Technology. 2007;98(18):3634–3637. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin L, Herrmann C, Papinutti VL. Optimization of lignocellulolytic enzyme production by the white-rot fungus Trametes trogii in solid-state fermentation using response surface methodology. Biochemical Engineering Journal. 2008;39(1):207–214. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maes C, Delcour JA. Alkaline hydrogen peroxide extraction of wheat bran non-starch polysaccharides. Journal of Cereal Science. 2001;34(1):29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beaugrand J, Reis D, Guillon F, Debeire P, Chabbert B. Xylanase-mediated hydrolysis of wheat bran: evidence for subcellular heterogeneity of cell walls. International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2004;165(4):553–563. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaouani A, Guillén F, Penninckx MJ, Martínez AT, Martínez MJ. Role of Pycnoporus coccineus laccase in the degradation of aromatic compounds in olive oil mill wastewater. Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 2005;36(4):478–486. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoke AT. Economical second-order designs based on irregular fractions of the 3n factorial. Technometrics. 1974;16(3):375–384. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aissa I, Bouaziz M, Ghamgui H, et al. Optimization of lipase-catalyzed synthesis of acetylated tyrosol by response surface methodology. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2007;55(25):10298–10305. doi: 10.1021/jf071685q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathieu D, Nony J, Phan-Tan-Luu R. NEMROD-W Software. Marseille, France: LPRAI; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zadrazil F, Brunnert H. Investigation of physical parameters important for the solid state fermentation of straw by white rot fungi. European Journal of Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 1981;11(3):183–188. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pandey A. Solid-state fermentation. Biochemical Engineering Journal. 2003;13(2-3):81–84. doi: 10.1016/s1369-703x(00)00065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pandey A. Recent process developments in solid-state fermentation. Process Biochemistry. 1992;27(2):109–117. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sabu A, Pandey A, Jaafar Daud M, Szakacs G. Tamarind seed powder and palm kernel cake: two novel agro residues for the production of tannase under solid state fermentation by Aspergillus niger ATCC 16620. Bioresource Technology. 2005;96(11):1223–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sutherland GRJ, Aust SD. The effects of calcium on the thermal stability and activity of manganese peroxidase. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1996;332(1):128–134. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bennamoun L, Meraihi Z, Dakhmouche S. Utilisation de la planification expérimentale pour l’optimisation de la production de l’α-amylase par Aspergillus oryzaeAhlburg (Cohen) 1042.72 cultivé sur milieu à base de déchets d’oranges. Journal of Food Engineering. 2004;64(2):257–264. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pandey A, Soccol CR, Mitchell D. New developments in solid state fermentation: I-bioprocesses and products. Process Biochemistry. 2000;35(10):1153–1169. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galhaup C, Wagner H, Hinterstoisser B, Haltrich D. Increased production of laccase by the wood-degrading basidiomycete Trametes pubescens. Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 2002;30(4):529–536. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schlosser D, Grey R, Fritsche W. Patterns of ligninolytic enzymes in Trametes versicolor. Distribution of extra- and intracellular enzyme activities during cultivation on glucose, wheat straw and beech wood. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 1997;47(4):412–418. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prasad KK, Mohan SV, Rao RS, Pati BR, Sarma PN. Laccase production by Pleurotus ostreatus 1804: optimization of submerged culture conditions by Taguchi DOE methodology. Biochemical Engineering Journal. 2005;24(1):17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Collins PJ, Dobson ADW. Regulation of laccase gene transcription in Trametes versicolor. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1997;63(9):3444–3450. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3444-3450.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palmieri G, Giardina P, Bianco C, Fontanella B, Sannia G. Copper induction of laccase isoenzymes in the ligninolytic fungus Pleurotus ostreatus. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2000;66(3):920–924. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.3.920-924.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soden DM, Dobson ADW. Differential regulation of laccase gene expression in Pleurotus sajor-caju. Microbiology. 2001;147(7):1755–1763. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-7-1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Faraco V, Giardina P, Sannia G. Metal-responsive elements in Pleurotus ostreatus laccase gene promoters. Microbiology. 2003;149(8):2155–2162. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26360-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kashyap P, Sabu A, Pandey A, Szakacs G, Soccol CR. Extra-cellular L-glutaminase production by Zygosaccharomyces rouxii under solid-state fermentation. Process Biochemistry. 2002;38(3):307–312. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramachandran S, Patel AK, Nampoothiri KM, et al. Coconut oil cake—a potential raw material for the production of α-amylase. Bioresource Technology. 2004;93(2):169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2003.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sabu A, Pandey A, Jaafar Daud M, Szakacs G. Tamarind seed powder and palm kernel cake: two novel agro residues for the production of tannase under solid state fermentation by Aspergillus niger ATCC 16620. Bioresource Technology. 2005;96(11):1223–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kareem SO, Akpan I, Oduntan SB. Cowpea waste: a novel substrate for solid state production of amylase by Aspergillus oryzae. African Journal of Microbiology Research. 2009;3(12):974–977. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thiyagarajan A, Kaviyarasan V, Karrunakaran CM. Optimization of process parameters for the production of thermostable laccase by Pleurotus flabellatus ATK-1 using response surface methodology. International Journal of Current Research. 2010;7:058–061. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arora DS, Gill PK. Laccase production by some white rot fungi under different nutritional conditions. Bioresource Technology. 2000;73(3):283–285. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Galhaup C, Haltrich D. Enhanced formation of laccase activity by the white-rot fungus Trametes pubescens in the presence of copper. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2001;56(1-2):225–232. doi: 10.1007/s002530100636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Couto SR, Rosales E, Gundín M, Sanromán MÁ. Exploitation of a waste from the brewing industry for laccase production by two Trametes species. Journal of Food Engineering. 2004;64(4):423–428. [Google Scholar]