Abstract

Although an important role for the amygdala in taste aversion learning has been suggested by work in a number of laboratories, results have been inconsistent and interpretations varied. The present series of studies reevaluated the role of the amygdala in taste aversion learning by examining the extent to which conditioning methods, testing methods and lesioning methods, influence whether amygdala lesions dramatically affect conditioned taste aversion (CTA) learning. Results indicated that when animals are conditioned with an intraoral (I/O) taste presentation, lesions of amygdala eliminate evidence of conditioning whether animals are tested intraorally or with a two-bottle solution presentation. Dramatic effects of amygdala lesions on CTA learning were seen whether lesions were made electrolytically or using an excitotoxin. In contrast, when animals were conditioned using bottle presentation of the taste, electrolytic lesions attenuated CTAs but did not eliminate them, and excitotoxic lesions had no effect. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that neural structures critical for CTA learning may differ depending on the extent to which the method of conditioned stimulus delivery incorporates a response component.

Taste aversion learning is a robust form of associative learning in which animals and humans learn to avoid a taste or flavor that has been followed by gastrointestinal malaise (Garcia et al. 1974; Bernstein 1991). In the laboratory, conditioned taste aversions (CTAs) are commonly established in a single trial by exposing animals to a taste conditioned stimulus (CS) followed by administration of a malaise-producing drug, such as LiCl [unconditioned stimulus (US)].

Taste aversion learning has received extensive experimental attention (e.g., see Riley and Clarke 1977). However, unlike other defensive conditioning paradigms, a clear definition of the neural circuitry underlying this unusual type of learning has yet to emerge (Chambers 1990; Yamamoto 1993). Recent studies have pointed to the importance of the pontine parabrachial nucleus (PBN) in acquisition but not expression of CTAs (Reilly et al. 1993; Grigson et al. 1997). However, because the chronic decerebrate rat is unable to acquire a CTA (Grill and Norgren 1978), forebrain structures appear to be necessary for CTA learning. Identification of those structures, however, has remained elusive. Studies examining the effects of amygdala lesions on CTA learning have been particularly inconsistent. Several laboratories report that lesions of the amygdala significantly interfere with CTA learning (Nachman and Ashe 1974; Lasiter and Glanzman 1985; Simbayi et al. 1986; Gallo et al. 1992; Kesner et al. 1992; Yamamoto et al. 1995), whereas others find little or no effect (Bermudez-Rattoni and McGaugh 1991; Hatfield et al. 1992; Galaverna et al. 1993). Of those who do find effects, some point to the importance of the central nucleus (Lasiter and Glanzman 1985), whereas others have implicated the basolateral nucleus (Nachman and Ashe 1974; Simbayi et al. 1986; Yamamoto and Fugimoto 1991; Yamamoto 1993). Finally, a compelling case has been made that when amygdala lesions do interfere with CTA learning, the effect is principally owing to damage to fibers passing from insular cortex through amygdala (Dunn and Everitt 1988).

In contrast to these variable results, our laboratory recently obtained clear and consistent effects of lesions of the amygdala on CTA learning (Schafe and Bernstein 1996). The striking result was the complete elimination of evidence of CTA conditioning in lesioned animals, an observation that contrasts with that of the majority of prior studies that have found attenuation, but not necessarily elimination, of CTA learning after amygdala lesions (Yamamoto and Fujimoto 1991; Gallo et al. 1992; Kesner et al. 1992). One key difference between our amygdala lesion studies and those of other laboratories was that our CTA studies used direct infusion of CS solutions into the oral cavity both during conditioning and testing (see Fig. 1, top), largely because of our interest in a striking cellular correlate of CTA expression, c-Fos induction in the intermediate division of the nucleus of the solitary tract (iNTS) (Swank and Bernstein 1994). This involuntary CS-delivery protocol contrasts with most CTA studies in the literature in which animals initiate CS exposure voluntarily by drinking solution from a bottle (see Fig. 1, bottom) and, as such, could be an important procedural factor in determining whether amygdala lesions significantly affect taste aversion learning.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of different methods used to establish a CTA. Rats are either infused intraorally with a CS taste solution followed by injection with toxic drug, such as LiCl (top), or are allowed to drink the CS taste solution from a bottle followed by the same drug (bottom).

These considerations led us to systematically examine whether conditioning, testing, and/or lesioning methods influence the effects of amygdala lesions on CTA learning. Given the variability in results of past studies evaluating effects of amygdala lesions on CTA, we chose to lesion the entire amygdala rather than evaluate the role of specific subnuclei. Results indicated that when animals were conditioned with an intraoral (I/O) CS presentation, lesions of amygdala eliminated evidence of conditioning whether animals were tested intraorally or with a two-bottle solution presentation. Elimination of aversions was found whether lesions were made electrolytically or using an excitotoxin. In contrast, when animals were conditioned using a more conventional bottle presentation of the CS, electrolytic lesions of amygdala attenuated CTAs but did not eliminate them, whereas excitotoxic lesions had no effect. Thus, the involvement of amygdala in CTA learning appears to depend on the extent to which the delivery of the CS in the conditioning protocol incorporates a response requirement.

General Methods

SUBJECTS

Adult male Long–Evans rats were obtained from the breeding colony maintained at the University of Washington. At the time of surgery, free-feeding body weights ranged from 300 to 400 grams. Rats were housed individually in suspended stainless steel cages and maintained on a 12:12-hr light/dark cycle. Teklad rodent chow and water were provided ad libitum unless otherwise indicated.

LESIONS

Under Equithesin (3.3 mg/kg) anesthesia, rats were first implanted with an I/O cannula and then given either bilateral lesions of the amygdala or SHAM operations. The oral cannula was constructed of 100-gauge polyethylene tubing and was inserted with a 19-gauge sharpened stainless steel probe. The probe was inserted through the roof of the mouth just anterolateral to the first maxillary molar and passed through the cheek, caudal to the eye, to exit the scapular area behind the head. Electrolytic lesions of the amygdala were produced by passage of 20 sec of 2-mA anodal current through an exposed tip of a Teflon-insulated tungsten electrode (0.008 inch, A.M. Systems, Everett, WA). Lesion coordinates, taken from Paxinos and Watson (1986) and adjusted with pilot data, were 1.80–3.30 mm posterior to bregma, 4.4–4.7 mm lateral to the midline, and 8.2–8.8 mm ventral to the skull surface (for a total of four penetrations). For SHAM animals, the skull was opened and the dura penetrated, but no lesion was made. Excitotoxic lesions of the amygdala were produced using ibotenic acid. A single penetration was made on each side of the brain, at the following coordinates: 2.50 mm posterior to bregma, 4.4 mm lateral to the midline, and 8.1 mm ventral to the skull surface. A 23-gauge guide cannula was attached to the manipulator arm of the stereotaxic device. Ibotenic acid (RBI; 10 mg/ml, 0.5 μl) was dissolved in sterile PBS and infused slowly (0.1 μl/min) via infusion pump through a 30-gauge injector cannula. Following infusion, the injector cannula was left in place for an additional 5 min to allow diffusion of the toxin from the cannula tip. At the time of surgery, rats received 0.2 ml of Gentamicin sulfate (40 mg/ml, i.m.) as a prophylaxis against infection. Weights were taken every other day, and animals were given at least 7 days to recover prior to habituation and conditioning.

HISTOLOGY

To verify the location and completeness of the lesions, 50-μm sections were cut in the transverse plane throughout a 3-mm region circumscribing the amygdala. Every other section was mounted onto gelatin-coated glass slides. Sections were air dried, stained for Nissl using Cresyl violet, dehydrated in ethanol, cleared in Histoclear, and coverslipped using Permount. Camera lucida drawings of sections were prepared and examined using a projection light microscope. Sections were air-dried, stained for Nissl using Cresyl violet, dehydrated in ethanol, cleared in Histoclear, and coverslipped using Permount. Camera lucida drawings of sections were prepared and examined using a projection light microscope. Sections were analyzed by comparing them with those found in Swanson (1994).

Experiment 1: Evaluation of Testing Method on the Effects of Electrolytic Amygdala Lesions on CTA Learning

In the first experiment, rats with bilateral electrolytic lesions of amygdala were conditioned using an I/O solution presentation (Fig. 1, top). Previous studies in our laboratory have shown complete elimination of CTA learning in amygdala-lesioned rats conditioned with this method (Schafe and Bernstein 1996). Those studies did not, however, evaluate whether the elimination of CTA learning following I/O conditioning generalizes to other types of testing situations. In this experiment, we therefore used both I/O tests and a more conventional two-bottle test to evaluate this question.

Materials and Methods

HABITUATION AND CONDITIONING

In the 5 days following cannula implantation and electrolytic lesions, the oral cannula was flushed every other day with distilled water to prevent clogging. Two days prior to conditioning, rats were habituated to Plexiglas cylindrical chambers that were to be used during conditioning. On each habituation day, rats were placed in a cylinder for 30 min and infused intraorally by infusion pump with 5 ml of distilled water at a rate of 0.5 ml/min. Rats in each surgical group (SHAM and Lesion) were assigned to experimental groups: SHAM–Paired (n = 5), SHAM–Unpaired (n = 5), Lesion–Paired (n = 7), and Lesion–Unpaired (n = 5).

On the conditioning day, experimental (“paired”) animals recived a single conditioning trial within the chamber consisting of I/O exposure to 5 ml of 0.15% saccharin at a rate of 0.5 ml/min followed immediately by injection of 0.15 m LiCl (20 ml/kg, i.p.). Control (“unpaired”) animals were infused with saccharin followed by injection of an equivalent volume of 0.15 m NaCl. Rats were videotaped during infusions to later assess the latency to which any rejection responses (described below) occurred. On the day following conditioning, paired animals received noncontingent injections of 0.15 m NaCl, whereas unpaired animals received noncontingent injections of 0.15 m LiCl. This was done to ensure equivalent exposure to LiCl (US) and saccharin (CS), with the only difference between groups being whether the two stimuli were paired.

TESTING

Two days following conditioning, rats were subjected to two types of tests to assess CTAs: latency to reject I/O infusion of the taste CS and the more commonly used two-bottle choice test with water. For the I/O test, rats were placed in the chamber and reinfused intraorally with the CS taste (5 ml, 0.5 ml/min). As during conditioning, animals were videotaped for subsequent analysis of rejection responses. Following saccharin infusion, rats were returned to their home cage. For the two-bottle test, rats were given a 12-hr two-bottle preference test between 0.15% saccharin and water. The order of I/O and two-bottle tests was counterbalanced such that half the rats in each group received the I/O test first and half received the two-bottle test first.

QUANTIFICATION OF BEHAVIOR

Videotapes of animals exposed to the CS taste during the I/O test were viewed and scored by an observer blind to experimental condition. For each rat, latency to reject the saccharin was recorded. As in our previous studies, rejection latency was defined in terms of the time elapsing between onset of the I/O infusion and the onset of persistent, passive dripping of the solution from the oral cavity. Mann-Whitney U-tests were used to evaluate differences between groups. For the two-bottle test, solution intake was measured to the nearest gram. Data were analyzed with analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc t-tests.

Results and Discussion

I/O TEST

Mean latency to reject the I/O infusion of CS saccharin following conditioning is presented in Figure 2. Consistent with our previous findings (Schafe and Bernstein 1996), paired rats with lesions of amygdala showed virtually no evidence of aversion conditioning, ingesting the saccharin throughout most of the 10-min infusion period and appearing indistinguishable from unpaired controls. Mann-Whitney U-tests determined that the effects of both saccharin–drug pairing and lesion on time to reject were significant (Sham–Paired vs. Sham–Unpaired, P < 0.01; Sham–Paired vs. Lesion–Paired, P < 0.01; Sham–Paired vs. Lesion–Unpaired, P < 0.01). No differences were detected between paired and unpaired lesioned animals or Sham–Unpaired animals and the lesioned groups. Thus, when conditioned and tested intraorally, rats with bilateral electrolytic lesions of amygdala show no evidence of aversion conditioning.

Figure 2.

Mean rejection latency (±s.e.) of SHAM and electrolytically lesioned animals during I/O saccharin infusion at the time of testing. Saccharin had either been paired (hatched bars) or unpaired (solid bars) with LiCl using I/O conditioning. (**) P < 0.01 relative to unpaired controls (experiment 1).

TWO-BOTTLE TEST

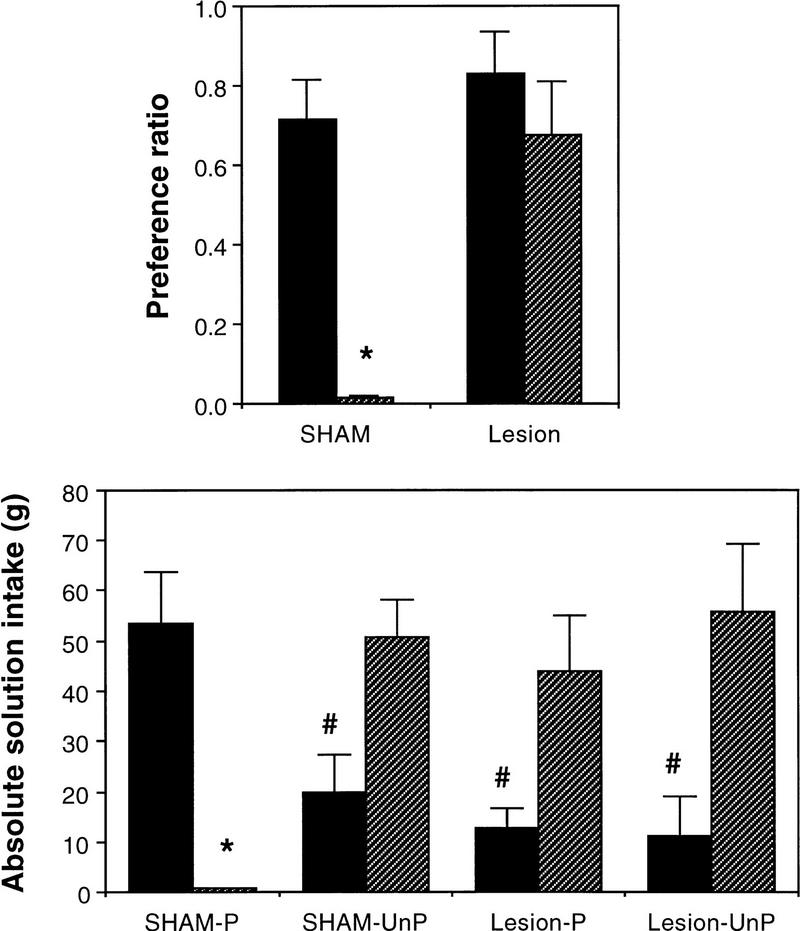

Preference ratios and absolute solution intake of both the saccharin CS and water are presented in Figure 3 (top and bottom, respectively). Consistent with the results of the I/O test, paired rats with lesions of amygdala showed virtually no evidence of aversion conditioning, displaying a clear preference for the saccharin CS over the water and appearing indistinguishable from unpaired controls. Results of the ANOVA revealed a significant main effect for saccharin–drug pairing, [F(1,18) = 14.67, P < 0.01], a significant effect for lesion, [F(1,18) = 12.03, P < 0.01], and a significant drug pairing by lesion interaction [F(1,18) = 6.06, P < 0.05]. These results are also reflected in the absolute solution intakes, in which intake of the saccharin in both lesioned groups (paired and unpaired) was statistically indistinguishable from that of unpaired animals. Thus, when conditioned intraorally, rats with electrolytic lesions of amygdala show no evidence of aversion conditioning in either an involuntary I/O test or a voluntary two-bottle preference test, indicating that the effect of amygdala lesions was independent of the type of test used to assess conditioning.

Figure 3.

(top) Mean (±s.e.) preference ratios for SHAm and electrolytically lesioned animals following 12-hr two-bottle test between saccharin and water. Saccharin had either been paired (hatched bars) or unpaired (solid bars) with LiCl using I/O conditioning. (Bottom) Mean (±s.e.) absolute solution intake of water (solid bars) and saccharin (hatched bars) during the same test. (*) P < 0.01 relative to unpaired controls; (#) P < 0.01 relative to water intake in SHAM–Paired controls (experiment 1).

Experiment 2: Evaluation of Conditioning Method on the Effects of Electrolytic Amygdala Lesions on CTA Learning

In the previous experiment, we showed that electrolytic lesions of amygdala eliminate evidence of CTA learning in rats conditioned with the I/O method, regardless of whether they are tested intraorally or with a more conventional two-bottle test. In this experiment, a more conventional conditioning method was used; namely, rats with comparable electrolytic lesions of amygdala were exposed during conditioning to the CS taste by drinking the solution from a bottle (Fig. 1, bottom).

Materials and Methods

HABITUATION AND CONDITIONING

One week following the placement of electrolytic lesions, rats were acclimated to a water deprivation schedule consisting of 1.5 hr of access to water per day, divided into two drinking periods. One-half hour of water access was followed by an additional hour of hydration several hours later. Prior to conditioning, rats were given 3 days of habituation to drinking in the cylindrical chambers by allowing them their initial half hour of water access from a drinking tube attached to the chamber wall. Prior to conditioning, rats in each surgical group (SHAM and Lesion) were assigned to experimental groups: SHAM–Paired (n = 5), SHAM–Unpaired (n = 4), Lesion–Paired (n = 5), and Lesion–Unpaired (n = 4).

On the conditioning day, paired animals received a single conditioning trial within the chamber consisting of half an hour of access to a bottle of 0.15% saccharin followed immediately by injection of 0.15 m LiCl (20 ml/kg, i.p.). Unpaired animals were given access to the saccharin followed by injection of an equivalent volume of 0.15 m NaCl. On the day following conditioning, rats received noncontingent injections as in experiment 1. All rats were returned to ad libitum access to water and given an additional week to recover from conditioning and deprivation prior to testing.

TESTING

On the test day, rats were given a 12-hr two-bottle preference test between 0.15% saccharin solution and water as described in Experiment 1.

Results and Discussion

Preference ratios and absolute solution intake of both the saccharin CS and water are presented in Figure 4 (top and bottom, respectively). Unlike the results of the previous experiment, paired lesioned animals showed evidence of aversion conditioning, although aversions were weaker than those of unlesioned animals. Results of the ANOVA on saccharin preference ratios revealed a significant main effect for saccharin–drug pairing [F(1,14) = 24.46, P <0.01] and a significant effect for lesion [F(1,14) = 8.67, P < 0.01]. The interaction, however, was not found to be significant.

Figure 4.

(Top) Mean (± s.e.) preference ratios for SHAM and electrolytically lesioned animals following 12-hr two-bottle test between sacharin and water. Saccharin had either been paired (hatched bars) or unpaired (solid bars) with LiCl using bottle conditioning. (Bottom) Mean (±s.e.) absolute solution intake of water (solid bars) and saccharin (hatched bars) during the same test. (*) P < 0.01 relative to unpaired controls; (#) P < 0.01 relative to water intake in SHAM–Paired controls (experiment 2).

At first glance, the pattern of results for saccharin preference ratios in Figures 3 (I/O conditioning) and 4 (bottle conditioning) appears similar except that the paired versus unpaired lesion groups achieve significance in the second experiment. However, the difference between the first and second experiment emerges more clearly when absolute intakes are examined. Here, it can be seen that in the first experiment the pattern of saccharin intake of Lesion–Paired and Lesion–Unpaired animals is remarkably similar; both groups drink much more saccharin than water (Fig. 3, bottom). This is contrasted with intakes of animals in the second experiment where Lesion–Unpaired animals markedly prefer saccharin to water, whereas Lesion–Paired animals drink about equal amounts of the two fluids (Fig. 4, bottom). Statistically, this was confirmed; Lesion–Paired animals consumed less saccharin than unpaired controls (P < 0.05), although their intake was still higher than that of SHAM–Paired animals. Thus, unlike results when animals were trained using the I/O method, rats with electrolytic amygdala lesions that were trained using a bottle showed evidence of CTA learning; there was attenuation but not elimination of the learning.

Because Figures 3 and 4 display the same dependent measures after conditioning with two different methods, they allow us to assess whether the strength of conditioning with bottle and I/O presentations are comparable. A comparison of Sham–Paired animals in the two studies provides evidence that the tendency to avoid the LiCl-paired saccharin is comparable despite the use of two different conditioning methods. Thus, differences in the effects of amygdala lesions on CTA learning do not appear to be attributable to differences in the strength of the learning.

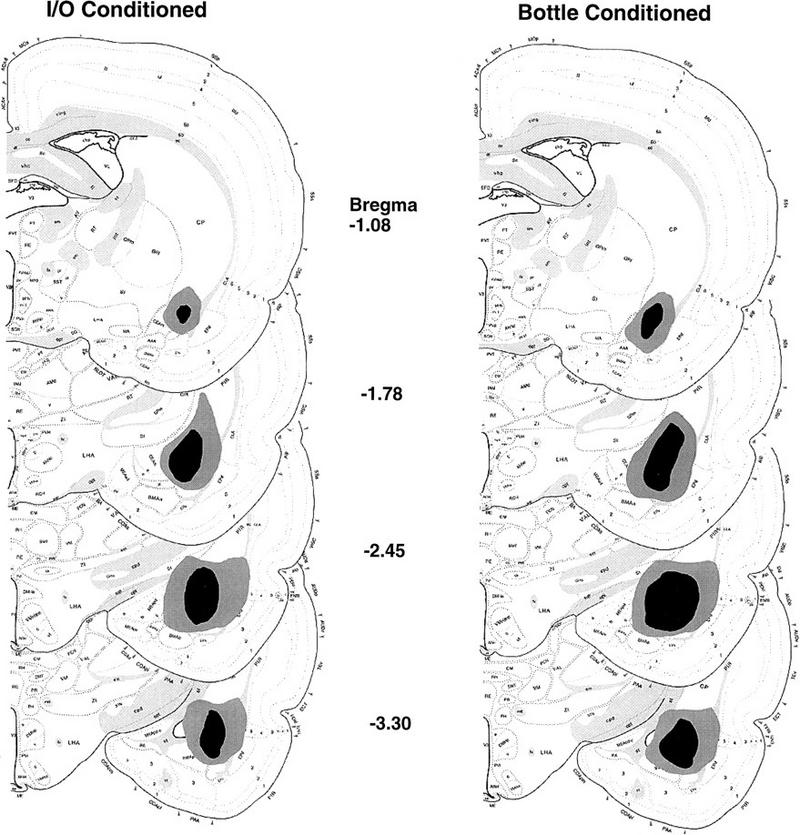

HISTOLOGY

Reconstructions of the rostrocaudal extent of electrolytic amygdala lesions in experiments 1 (I/O conditioning) and 2 (bottle conditioning) are presented on the left and right sides of Figure 5, respectively. Examination of the sections revealed that lesioned animals sustained damage to a variety of subnuclei of the amygdala, including the basolateral, lateral, and central amygdaloid nuclei. In most animals, some damage to the ventral aspect of the globus pallidus and striatum was also noted. A few animals had damage to the lateral aspect of the internal capsule. A careful comparison of lesions in the first and second experiments indicates that the lesions were comparable. If anything, the lesions in the second study were somewhat more extensive. Thus, the observed differences in degree of interference with CTA learning in the two studies cannot be attributed to incomplete or smaller lesions in experiment 2.

Figure 5.

Serial reconstructions of electrolytic amygdala lesions in the transverse plane. (Left) The extent of the lesions in experiment 1, in which animals were conditioned intraorally. (Right) The extent of the lesions in experiment 2, in which rats were conditioned with a bottle. The lightly and darkly shaded regions correspond to the largest and smallest lesions, respectively.

Experiment 3: Evaluation of Lesioning Method on the Effects of Amygdala Lesions on CTA Learning

The previous two experiments used electrolytic lesions of amygdala. Consistent with previous findings, electrolytic lesions eliminated evidence of CTA learning in rats conditioned using the I/O method (Schafe and Bernstein 1996) and attenuated, but did not eliminate, evidence of conditioning in bottle-trained animals (Yamamoto and Fujimoto 1991; Gallo et al. 1992; Kesner et al. 1992). To determine whether one or both of these effects might be attributable to damage to fibers passing through amygdala (Dunn and Everitt 1988), the following set of experiments used excitotoxic lesions, which spare fibers of passage (Jarrard 1991). As before, conditioning methods involved both I/O solution presentation (experiment 3a) and bottle solution presentation (experiment 3b).

Materials and Methods

HABITUATION AND CONDITIONING

For experiment 3a, rats with I/O cannulas and bilateral ibotenic acid lesions of amygdala were habituated to chambers and I/O infusions as described previously and conditioned and tested using the I/O method of experiment 1. There were three groups in this experiment: SHAM–Paired (n= 3), Lesion–Paired (n = 10), and Lesion–Unpaired (n = 3). For experiment 3b, separate groups of similarly lesioned animals were conditioned using the bottle presentation methods of Experiment 2. There were also three groups in this experiment: SHAM–Paired (n = 5), Lesion–Paired (n = 7), and Lesion–Unpaired (n= 5).

TESTING

As in the previous experiments, on the test day rats were tested either by assessing the latency to reject I/O infusion of the taste CS (experiment 3a) or by a 12-hr two-bottle preference test between the CS solution and water (experiment 3b).

Results and Discussion

EXPERIMENT 3a

Mean latency to reject the I/O infusion of CS saccharin during testing is presented in Figure 6. It can be seen that excitotoxic lesions had essentially the same effect on CTA expression as electrolytic lesions; namely, lesioned animals showed little or no evidence of CTA learning. Aversions were evident in SHAM–Paired animals but not in Lesion–Paired animals; Lesion–Paired animals were significantly different from the SHAM–Paired (P < 0.05) but not the lesion–unpaired group. In fact, 8 of 10 animals in the Lesion–Paired group continued to ingest the saccharin throughout the 10-min infusion period, showing no signs of passive dripping.

Figure 6.

Mean rejection latency (±s.e.) of SHAM and excitotoxically lesioned animals during I/O saccharin infusion at the time of testing. Saccharin had either been paired (P) or unpaired (UnP) with LiCl using I/O conditioning. (*) P < 0.01 relative to lesioned groups (experiment 3a).

EXPERIMENT 3b

Preference ratios and absolute solution intake of both the saccharin CS and water are presented in Figure 7 (top and bottom, respectively). Unlike the results of the previous experiment, paired lesioned animals showed strong aversion conditioning (Lesion–Paired vs. Lesion–Unpaired, P < 0.01; Duncan’s test). Results of experiment 3b are in striking contrast with those of experiment 3a; in 3a no evidence of aversion conditioning is seen in lesioned animals, whereas in 3b aversion conditioning appears normal. The lesioning methods were identical, as were the CS and US. The most prominent difference between these two studies was the details of the conditioning method.

Figure 7.

(Top) Mean (±s.e.) preference ratios for SHAM and excitotoxically lesioned animals following 12-hr two-bottle test between saccharin and water. Saccharin had either been paired (P) or unpaired (UnP) with LiCl using bottle conditioning. (Bottom) Mean (±s.e.) absolute solution intake of water (solid bars) and saccharin (hatched bars) during the same test. (**) P < 0.01 relative to unpaired controls; (#) P < 0.01 relative to water intake in SHAM–Paired controls (experiment 3b).

HISTOLOGY

Reconstruction of the rostrocaudal extent of excitotoxic amygdala lesions in experiments 3a (I/O conditioned) and 3b (bottle conditioned) are presented on the left and right sides of Figure 8, respectively. Examination of the extent of gliosis revealed that lesioned animals sustained comparable damage to those in experiments 1 and 2, including the basolateral, lateral, and central amygdaloid nuclei and, to a lesser degree, the ventral aspect of the globus pallidus and striatum.

Figure 8.

Serial reconstructions of excitotoxic amygdala lesions in the transverse plane (experiment 3). (Left) Lesions in experiment 3a in which rats were conditioned with the I/O method. (Right) Lesions in experiment 3b in which rats were conditioned using a bottle. The lightly and darkly shaded regions correspond to the largest and smallest lesions, respectively.

Experiment 4: Assessment of the Effects of Amygdala Lesions on CTA Learning with the I/O Conditioning Method in Fluid-Deprived Animals

In the previous experiments, rats with bilateral lesions of amygdala were conditioned either intraorally or with a bottle presentation of the CS taste. However, the fluid deprivation status of the two procedures was not held constant across studies; I/O conditioning does not typically necessitate water deprivation, whereas bottle conditioning does. To control for this procedural difference, the following experiment replicated the I/O procedure of experiment 1 in rats with ibotenic acid lesions of amygdala. Before conditioning, however, these rats were placed on a water deprivation schedule so that that fluid deprivation status was equivalent to that of rats in experiment 2 that were trained with a bottle.

Materials and Methods

HABITUATION AND CONDITIONING

Rats with bilateral ibotenic acid lesions of amygdala were assigned to SHAM–paired (n = 6), Lesion–paired (n = 4), and Lesion–unpaired (n = 4) groups and habituated to chambers and I/O infusions as described previously. They were then conditioned and tested using the I/O method of experiment 1. However, these rats were also habituated and conditioned under a water deprivation regimen as in experiment 2. Thus, their fluid deprivation status at the time of conditioning was comparable to animals in experiments 2 and 3b that were conditioned using a bottle.

Results and Discussion

Mean latency to reject the I/O infusion of CS saccharin in fluid deprived rats with excitotoxic lesions is presented in Figure 9. Clearly, fluid deprivation is not a critical variable influencing whether amygdala lesions disrupt CTA learning. As in the first experiment, paired rats showed virtually no evidence of aversion conditioning relative to unpaired controls, whereas SHAM animals rejected the CS taste within 2–3 min (Mann-Whitney U-test, P < 0.01).

Figure 9.

Mean rejection latency (±s.e.) of SHAM and excitotoxically lesioned animals during I/O saccharin infusion at the time of testing. Saccharin had either been paired (P) or unpaired (UnP) with LiCl using I/O conditioning under conditions of fluid deprivation. (**) P < 0.01 relative to lesioned groups (experiment 4).

GENERAL DISCUSSION

The role of amygdala in CTA learning has remained controversial, and this controversy has clouded efforts to define the neural pathways critical to this unusual and robust type of learning. The present studies are the first, of which we are aware, to systematically examine the impact of different conditioning methods on the neural mediation of CTA learning. Results suggest a possible reason for the controversy involving amygdala and CTAs, namely that the involvement of amygdala in CTA learning can vary dramatically with the nature of the conditioning method used. Using an I/O CS infusion procedure, the amygdala appeared necessary for CTA expression. Conditioned animals with lesions of the amygdala were indistinguishable from unconditioned controls in their ingestive response to the CS taste. This was the case whether lesions were made electrolytically or using an axon-sparing excitotoxin. In marked contrast, when animals were conditioned in the more conventional way, by receiving CS exposure while drinking from a bottle, effects of amygdala lesions were less dramatic and were only seen with electrolytic lesions.

Most laboratories that study the impact of amygdala lesions on CTA learning utilize bottle-conditioning methods that require the animal to voluntarily approach and consume the CS solution before administration of the US drug (e.g., see Nachman and Ashe 1974; Lasiter and Glanzman 1982, 1985; Simbayi et al. 1986; Dunn and Everitt 1988; Bermudez-Rattoni and McGaugh 1991; Gallo et al. 1992; Hatfield et al. 1992; Kesner et al. 1992). The acquisition of CTAs under these circumstances is complex and appears to contain elements of both Pavlovian and instrumental learning (e.g., see Chambers 1990). The taste (CS)–illness (US) contingency, for example, may be characterized procedurally as Pavlovian conditioning, whereas the approach–illness (US) contingency may be characterized as instrumental learning. However, because it has no response requirement, the I/O conditioning method used in the present studies is one in which the Pavlovian components of CTA learning can be isolated from the more conventional method involving an approach component. The neural structures and pathways mediating different types of learning and memory have been shown to be dissociable (McDonald and White 1993). The amygdala, for example, has been shown to be essential for Pavlovian conditioning tasks, particularly aversive tasks (Lavond et al. 1993; McDonald and White 1993; Gallagher and Chiba 1996), whereas the dorsal striatum and hippocampus have been shown to be essential for learning tasks involving either a response or spatial requirement, respectively (e.g., see McDonald and White 1993, 1994, 1995). Consistent with these findings, the results of the present studies strongly imply that the importance of the amygdala to CTA learning depends heavily on whether the method of CS delivery is response contingent or not. When the conditioning procedure does not involve a response component (I/O method), amygdala lesions eliminate CTA acquisition. However, if the conditioning protocol does include a response requirement (bottle method), othermemory systems may be capable of acquisition and performance of the learned response in the amygdala-lesioned animal (McDonald and White 1993, 1994, 1995). Thus, procedural differences, which appear quite subtle, nonetheless apparently result in important differences in the neural circuitry that is recruited to mediate the learning.

Interestingly, the different effects of electrolytic and excitotoxic lesions on CTAs conditioned with the bottle method replicate the widely cited findings of Dunn and Everitt (1988). Using bottle-training methods, they found that electrolytic, but not excitotoxic, lesions of amygdala attenuated CTA learning. They interpreted their results to indicate that the amygdala is not involved in CTA learning and that when electrolytic lesions do affect CTA acquisition it is because of incidental damage to fibers of passage projecting to or originating in structures anterior to the amygdala, such as insular cortex (IC). This is a particularly relevant concern considering that lesions of IC are among the more consistent at eliminating acquisition and/or retention of CTA learning (Braun et al. 1982; Kiefer et al. 1984; Lasiter and Glanzman 1985; Dunn and Everitt 1988; Bermudez-Rattoni and McGaugh 1991). Consistent with the interpretations of Dunn and Everitt (1988), the present results also suggest a role for fibers of passage in CTA learning but only when the method of CS delivery involves a response requirement.

The strong interpretation of the results of the present studies, particularly the contrast between experiments 3a and 3b, is that when taste aversions are conditioned conventionally, using a bottle, amygdala is not involved. On the other hand, when conditioning is accomplished using an I/O CS presentation, amygdala is indispensable. Our resistance to accepting this strong view stems largely from considering evidence from those laboratories that have found effects on CTA learning using traditional training (bottle) methods and the placement of excitotoxic lesions in amygdala (Yamamoto et al. 1995; S. Frey, R. Morris, and M. Petrides, unpubl.). Recent studies, furthermore, have found significant effects on bottle-trained CTAs following the infusion of protein synthesis inhibitors (Lamprecht and Dudai 1996), CREB antisense (Lamprecht and Dudai 196; Lamprecht et al. 1997) or inhibitors of protein kinase C (Yasoshima and Yamamoto 1997) directly into the amygdala, implicating the amygdala in the experience-dependent plastic changes that underlie CTA acquisition. Collectively, this work provides support for a role for amygdala in CTAs when bottle conditioning methods are used. Thus, it is possible that our failure to find effects of excitotoxic lesions of amygdala on CTAs conditioned with a bottle was attributable ue to insensitivity of our testing methods. The present data certainly provide convincing evidence that the role of amygdala differs markedly depending on the conditioning protocol, but the overall importance of the amygdala in the traditional CTA paradigm remains to be determined.

The clear demonstration that the methods used to condition a taste aversion dramatically affect whether amygdala-lesioned animals are able to demonstrate evidence of CTA learning is important for a number of reasons. Not only does it provide a potential explanation for the long-standing inconsistencies in this literature, but it strongly suggests that the neural circuitry recruited in a CTA learning task, like other learning tasks, varies in its anatomical distribution and complexity depending on key features of the conditioning procedure. These data are consistent with the view that multiple independent memory systems can underlie the acquisition of complex learning tasks (McDonald and White 1993, 1994, 1995). They also provide an interesting parallel to the literature on fear conditioning, another learning task of considerable robustness and adaptive significance, and promise that some of the progress that has been made in understanding the neural basis of fear conditioning can provide a useful model for a similar approach to taste aversion learning. The I/O taste aversion conditioning method has already been shown to have a number of advantages in this regard. We have demonstrated a reliable cellular correlate of a CTA, c-Fos expression in the iNTS, using this method. This cellular correlate has provided a powerful tool for definition of critical pathways (Schafe et al. 1995; Schafe and Bernstein 1996). Furthermore, the present results suggest that the circuitry critical to this learning paradigm is definable, perhaps because it is simpler and involves less redundancy. Whether the present findings imply that the two different conditioning protocols involve quite different neural circuitry or that there is overlap in circuitry but that the amygdala node is critical to the I/O but not the bottle-trained method remains to be determined. Nonetheless, the present findings necessitate more careful definition of CTA paradigms. It may then be possible to unambiguously address critical questions such as whether amygdaa involvement is primarily in acquisition, retention, or expression of a CTA and whether other parts of the circuit differ as markedly as a function of conditioning protocol, as well as which amygdaloid subnuclei are critical to this involvement.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant NS37040.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

Present address: Center for Neural Science, New York, New York 10003 USA.

References

- Bermudez-Rattoni F, McGaugh JL. Insular cortex and amygdala lesions differentially affect acquisition on inhibitory avoidance and conditioned taste aversion. Brain Res. 1991;549:165–170. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90616-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein IL. Flavor aversion. In: Getchell TV, Doty RL, Bartoshuk LM, Snow JB, editors. Smell and taste in health and disease. New York, NY: Raven Press; 1991. pp. 417–428. [Google Scholar]

- Braun JJ, Lasiter PS, Kiefer SW. The gustatory neocortex of the rat. Physiol Psychol. 1982;10:13–45. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers KC. A neural model of conditioned taste aversions. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1990;13:373–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.002105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LT, Everitt BJ. Double dissociations of the effects of amygdala and insular cortex lesions on conditioned taste aversion, passive avoidance, and neophobia in rat using the excitotoxin ibotenic acid. Behav Neurosci. 1988;102:3–23. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.102.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaverna OG, Seeley RJ, Berridge KC, Grill HJ, Epstein AN, Schulkin J. Lesions of the central nucleus of the amygdala. I: Effects on taste reactivity, taste aversion learning and sodium appetite. Behav Brain Res. 1993;59:11–17. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90146-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher M, Chiba AA. The amygdala and emotion. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;6:221–227. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo M, Roldan G, Bures J. Differential involvement of gustatory insular cortex and amygdala in the acquisition and retrieval of conditioned taste aversion in rats. Behav Brain Res. 1992;52:91–97. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(05)80328-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia J, Hankins WG, Rusiniak KW. Behavioral regulation of the milieu interne in man and rat. Science. 1994;185:824–831. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4154.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigson PS, Shimura T, Norgren R. Brainstem lesions and gustatory function: III. The role of the nucleus of the solitary tract and the parabrachial nucleus in retention of a conditioned taste aversion in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111:180–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill HJ, Norgren R. Chronically decerebrate rats demonstrate satiation but not bait shyness. Science. 1978;201:267–269. doi: 10.1126/science.663655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield T, Graham PW, Gallagher M. Taste-potentiated odor aversion learning: Role of amygdaloid basolateral complex and central nucleus. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106:286–293. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrard LE. Use of ibotenic acid to selectively lesion brain structures. Methods Neurosci. 1991;7:58–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP, Berman RF, Tardif R. Place and taste aversion learning: Role of basal forebrain, parietal cortex, and amygdala. Brain ResBull. 1992;29:345–353. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(92)90066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer SW, Leach LR, Braun JJ. Taste agnosia following gustatory neocortex ablation: Dissociation from odor and generality across taste qualities. Behav Neurosci. 1984;98:590–608. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.98.4.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamprecht R, Dudai Y. Transient expression of c-Fos in rat amygdala during training is required for encoding conditioned taste aversion memory. Learn & Mem. 1996;3:31–41. doi: 10.1101/lm.3.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamprecht R, Hazvi S, Dudai Y. cAMP response element-binding protein in the amygdala is required for long- but not short- term conditioned taste aversion memory. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8443–8450. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08443.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasiter PS, Glanzman DL. Cortical substrates of taste aversion learning: Dorsal prepiriform (insular) lesions disrupt taste aversion learning. Brain Res Bull. 1982;29:345–353. doi: 10.1037/h0077894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Cortical substrates of taste aversion learning: Involvement of dorsolateral amygdaloid nuclei and temporal neocortex in taste aversion learning. Behav Neurosci. 1985;99:257–276. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.99.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavond DG, Kim JJ, Thompson RF. Mammalian brain substrates of aversive classical conditioning. Annu Rev Psychol. 1993;44:317–342. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.44.020193.001533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RJ, White NM. A triple dissociation of memory systems: Hippocampus, amygdala, and dorsal striatum. Behav Neurosci. 1993;107:3–22. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Parallel information processing in the water maze: Evidence for independent memory systems involving dorsal striatum and hippocampus. Behav Neural Biol. 1994;61:260–270. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(05)80009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Hippocampal and nonhippocampal contributions to place learning in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1995;109:579–593. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.109.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachman M, Ashe JH. Effects of basolateral amygdala lesions on neophobia, learned taste aversions, and sodium appetite in rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1974;87:622–643. doi: 10.1037/h0036973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 2nd ed. Orlando. FL: Academic Press; 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly S, Grigson PS, Norgren R. Parabrachial nucleus lesions and conditioned taste aversion: Evidence supporting an associative deficeit. Behav Neurosci. 1993;107:1005–1017. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley AL, Clarke CM. Conditioned taste aversions: A bibliography. In: Barker LM, Best MR, Domjan M, editors. Learning mechanisms in food selection. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Schafe GE, Bernstein IL. Forebrain contribution to the induction of a brainstem correlate of conditioned taste aversion: I. The amygdala. Brain Res. 1996;741:109–116. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)00906-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafe GE, Seeley RJ, Bernstein IL. Forebrain contribution to the induction of a cellular correlate of conditioned taste aversion in the nucleus of the solitary tract. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6789–6796. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06789.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simbayi LC, Boakes RA, Burton MJ. Effects of basolateral amygdala lesions on taste aversion produced by lactose and lithium chloride in the rat. Behav Neurosci. 1986;100:455–465. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.100.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swank MW, Bernstein IL. cFos induction in response to a conditioned stimulus after single trial taste aversion learning. Brain Res. 1994;636:202–208. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swank MW, Schafe GE, Bernstein IL. c-Fos induction in response to taste stimuli previously paired with amphetamine or LiCl during taste aversion learning. Brain Res. 1995;673:251–261. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)01421-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T. Neural mechanisms of taste aversion learning. Neurosci Res. 1993;16:181–185. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(93)90122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Fujimoto Y. Brain mechanisms of taste aversion learning in the rat. Brain Res Bull. 1991;27:403–406. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(91)90133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Fujimoto Y, Shimura T, Sakai N. Conditioned taste aversion in rats with excitotoxic brain lesions. Neurosci Res. 1995;1:31–49. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(95)00875-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasoshima Y, Yamamoto T. Rat gustatory memory requires protein kinase C activity in the amygdala and cortical gustatory area. Neuroreport. 1997;8:1363–1367. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199704140-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]