During the first decade of the 21st century, a number of questions regarding the relationship between cardiac dysfunction and cancer treatment have been answered. These questions arose, in part, because the tenet of primum non nocere (first, do no harm) gains special meaning in the treatment of cancer patients: regardless of whether our treatments are physical (as in the case of radiation), chemical (in the form of chemotherapy), or biologic (in the form of biologic response modifiers), they have some capacity to affect our patients adversely. The reality is that we have not yet achieved interventions that pose no risks. Awareness of the need to balance the goals of the oncologist (to maximally kill cancer cells or inhibit tumor cell division, vascularization, and spread) with those of the cardiologist (to protect the heart from damage related to the tumor or its treatment) goes back at least to the classic report by von Hoff and colleagues1 in the mid-1970s, which plotted the relationship between the extent of congestive heart failure and the dosage of doxorubicin. The concept of oncologic cardiology already was an entity by the mid-1980s.2

The recognition of cardiac dysfunction as a consequence of cancer treatment was much simpler when anthracycline cardiotoxicity was the dominant concern. We knew of the cumulative dose relationship as it applied to cardiac dysfunction; we knew that anthracyclines caused cell death; and we knew that, at least at the cellular level, the damage was permanent. We also understood that cardiac damage might well be subclinical and at the forefront only after compensatory mechanisms had been exhausted, which explained why cardiotoxicity might not be evident until years, or in some instances decades, after anthracycline treatment.

As several new anticancer agents with cardiovascular side effects entered the therapeutic armamentarium, a series of enigmas appeared; some have been answered, at least in part. For others, we can speculate, but we recognize that further study and interpretation will be required. Because modern cancer treatment can be “on target” insofar as it inhibits or destroys tumor cells and “off target” insofar as it affects normal cells, the achievement of balance is increasingly a consideration. When trastuzumab was first applied clinically, for example, up to 16% of patients treated with this monoclonal antibody developed significant heart failure.3 In subsequent observations and clinical trials through 2005, most patients who had been noted to have cardiac dysfunction appeared to stabilize and often to fully recover their cardiac reserves. Further clinical observations4 showed that trastuzumab could be used for long periods of time in many of our patients, which suggested that whatever was going on with this agent was clearly different from what had been seen with the anthracyclines. The concept of an alternative form of cardiotoxicity, different in mechanism and clinical course from what had been observed with the anthracyclines, gave rise to the formulation of an alternative or type II treatment-related cardiac dysfunction.5 The lack of anthracycline-typical cardiac structural changes and the presence of recovery potential suggest that some mechanism of myocyte functional impairment, rather than cellular death and consequent myocardial remodeling, is involved.6 This concept appears to be withstanding the test of time: in the 5 major adjuvant breast-cancer trials, there has been only 1 documented cardiac death due to progressive heart failure.7

A related question is that of the reversibility of cardiac dysfunction. While it was observed that the majority of patients regained some or most of their cardiac function after the administration of trastuzumab, and did so even in the absence of specific therapeutic intervention, some patients did not follow that path and retained either depressed cardiac contractility or symptomatic heart failure. How could a reversible injury sometimes not follow the usual path to recovery? One possible explanation is that most patients treated with trastuzumab had prior exposure to an anthracycline, and therefore had irreversible cellular destruction before receiving the monoclonal antibody. It is now known that anthracyclines are more cardiotoxic than had been understood initially, and this holds true even at submaximal cumulative dosages.8 Subsequent cellular dysfunction could place additional strain on the heart, further remodeling it and facilitating the cascade toward permanent cell loss. While this sequence of events is difficult to prove, several facts support such a mechanism: 1) the risk factors for cardiotoxicity associated with anthracyclines are similar to those associated with trastuzumab, 2) the tendency to recover appears to be higher in patients who have greater cardiac reserves, 3) trastuzumab lacks dose-related toxicity, 4) some patients recover even without specific pharmacologic intervention, and 5) deaths were scarce in the adjuvant breast-cancer clinical trials.

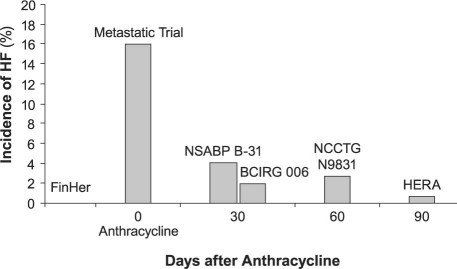

A further intriguing question with regard to trastuzumab is that of why cardiotoxicity was so much more prevalent in the early pivotal trial than was observed later. The pivotal trial reported a rate of severe heart failure of 16%, while the subsequent adjuvant trials noted rates in the 0 to 3.3% range (Fig. 1).7,9–14 Why was there such diversity in expression? Again here, the data are circumstantial and the proposed hypothesis involves the integration of a number of factors. We know, for example, that the doxorubicin-stressed heart exhibits increased human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) expression after doxorubicin exposure, indicating that HER2 (also known as ErbB2) may be a signaling pathway in the myocardium.15 This would explain why concomitant use of anthracycline and trastuzumab is more cardiotoxic than sequential use. Indeed, the differences in incidence, as shown by the data derived from trastuzumab trials, support this hypothesis, in that a longer interval between anthracycline and trastuzumab administration seems to be cardioprotective.

Fig. 1 The relationship between the observed incidence of heart failure (HF) and the time between the administration of doxorubicin and trastuzumab in the pivotal and adjuvant trastuzumab trials.

In the FinHer Trial (Finland Herceptin Study9), trastuzumab preceded the anthracycline; in the metastatic study (a Single Agent in First-Line Treatment of HER2-Overexpressing Metastatic Breast Cancer10), the drugs were given concomitantly; in the NSABP B-31 trial (National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-3111) and the BCIRG 006 (Breast Cancer International Research Group 00612), trastuzumab was given about 30 days after the anthracycline; in the NCCTG N9831 (North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 adjuvant breast cancer trial13) the interval was approximately 60 days; and in the HERA trial (Herceptin Adjuvant Trial14), the interval was approximately 90 days.

Modified from Ewer MS, Ewer SM. Cardiotoxicity of anticancer treatments: what the cardiologist needs to know. Nat Rev Cardiol 2010;7(10):564–75.7

Anthracyclines for Adjuvant Treatment

The change in the incidence of the various cancers over time is dependent on a host of factors: the rise in lung cancer deaths, for example, resulted from increased tobacco exposure, and the decline in gastrointestinal and uterine deaths is due, in large part, to improved screening and early curative intervention. In the case of breast cancer, the decline in deaths is related to several factors, which include earlier diagnosis through improved screening and more effective cure of breast cancer in the adjuvant setting. This hugely important step toward the elimination of the disease did not take place through a single breakthrough, but evolved over time: first with the adoption of adjuvant treatment, later with the addition and broad use of anthracyclines and taxanes, and more recently with the dramatic effect of trastuzumab for those whose cancers overexpress HER2. We now know that breast cancer represents a group of disorders and that its presentation as a clinical syndrome represents a common end-manifestation of a variety of environmental and genetic factors. It is now clear that through better treatments and earlier diagnosis, death is decreasing yearly; and molecular classification has helped us in the selection of therapeutic options for some groups of cancer patients. Especially intriguing is the discovery that a substantial number of patients do not need chemotherapy, due to the genetic profiles of their tumors. The incidence of anthracycline-associated heart failure is a particularly important concern for patients who are being treated in the adjuvant setting. Pinder and colleagues16 have shown a significant difference between patients aged 65 to 75 years who have been treated with anthracycline as part of the regimen, and those in the same age group who received non-anthracycline treatment or no adjuvant therapy. Interestingly, this observation has not held true for patients aged 75 years or older.16 It remains for us now to discover ways to further decrease the toxicity of our current therapies. In fact, one of the cardinal controversies with respect to breast cancer is the question of whether anthracyclines remain truly essential in the management of some forms of the disease. One trial17 reports that a combination of a taxane and cyclophosphamide improved survival, compared with a short course of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide. Future trials, we hope, will provide insight into this question. The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-46 trial has eliminated anthracyclines entirely from 2 of the treatment arms. The Breast Cancer International Research Group (BCIRG) 006 trial, in preliminary reports, has suggested that an alternative to anthracyclines does not compromise survival in patients treated in the adjuvant setting.12

Many questions remain with regard to cardiotoxicity in the wake of cancer treatment. The toxicity after anthracycline use is generally thought to cause permanent cell loss, which implies that treatment should follow the general guidelines for other forms of heart failure. The potential benefit of treatment for functional impairment that is reversible, especially when not severe, is less clear, and specific evidence of benefit is lacking. In addition, we do not know how long patients should be monitored, the best methods of monitoring them, or the ways in which newer techniques—such as the use of biomarkers like troponin I—will alter the present consensus that long-term follow-up is essential. Here, as in other matters affecting onco-cardiology, closer integration between the practitioners and the research scientists of both oncology and cardiology will further our understanding of this intriguing and rapidly evolving discipline.

Biomarkers in the Management of Cardiotoxic Cancer Drugs

One very clear fact has emerged in regard to treatment-related cardiac dysfunction: the prevention of damage is far more important than is therapeutic intervention to counteract ongoing damage. Among the more important recent innovations in this regard is our ability to detect troponins I and T as markers of myocyte death. It is now clear that the time elapsed from the end of chemotherapy to the onset of therapy for clinical heart failure is an important determinant of the extent of recovery from anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy. This highlights the need for early and real-time diagnosis of cardiac injury.18 Today, strong data indicate that troponin gives us the ability to detect chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity in its earliest phase, long before any reduction in left ventricular ejection fraction has occurred. Troponin now is the gold-standard biomarker for myocardial injury from any cause. The evaluation of troponin levels during high-dose chemotherapy enables the early identification of patients at risk of developing cardiac dysfunction and enables the stratification of cardiac risk after chemotherapy, thereby allowing for preventive therapy in selected high-risk patients.19–21 More recently, increases in troponin levels have been observed in patients treated with standard doses of anthracyclines, as well as in patients treated with some of the newer antitumor agents. In particular, in trastuzumab-treated patients, troponin can help to identify patients who have experienced cell death (and are therefore at higher risk of failure) to recover from cardiac dysfunction; this might help us to distinguish between reversible and irreversible cardiac damage.22 The possibility of identifying high-risk patients by means of troponin might lead to the targeted prevention of cardiotoxicity. Indeed, a prophylactic treatment with enalapril, in patients with early increases in troponin level after chemotherapy, seems to prevent cardiovascular disease and associated cardiac events, not only in high-dose anthracycline-treated patients, but also in patients treated with regimens that use standard-dose anthracycline and trastuzumab.21

The Symptom Management Gap

The management of debilitating symptoms associated with cancer and heart failure presents a major challenge to patients, families, and healthcare providers throughout the entire trajectory of the disease process. An optimal system of monitoring should alert clinicians to early heart failure, thereby providing the opportunity for intervention before patients become severely ill. Increasing patients' access to healthcare providers in the manner proposed by the Institute of Medicine23—through distance monitoring, not just face-to-face visits—is an approach to care that bridges the “quality chasm.” Multiple randomized clinical trials have shown the benefit of providing additional interactions between heart-failure patients and their healthcare providers; however, these studies have not included cancer patients.24 Optimal management of symptoms is dependent upon accurate symptom evaluation, as well as upon communication between patients and healthcare professionals. At MD Anderson, we evaluated the feasibility of using the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory-Heart Failure (MDASI-HF), a 27-item symptom-assessment instrument, programmed via the interactive voice response system (IVRS), in support of outpatient management of patients with cancer and concurrent heart failure.25 Twenty-six patients who developed heart failure as a complication of cancer therapy were enrolled in the study. Symptoms were monitored on a weekly basis for 3 months, using the MDASI-HF questionnaire via the IVRS. When a patient reported symptoms that reached a critical threshold, the system automatically generated an alert that prompted the nurse to triage the patient's response in accordance with protocol and to initiate interventions as appropriate (with physician approval). Patients could also gain access to the IVRS whenever they experienced worsening of symptoms. Clinical parameters and symptom scores were evaluated at baseline, and once a month thereafter for 3 months. The average usage rate of the IVRS for participants who were able to respond was 71%; the other 29% who developed complications after enrollment were not able to complete the IVRS due to hospitalization or transition to hospice. For this study, 115 critical threshold alerts were generated, which prompted notification of a physician, titration of a medication, and clinic visits of a nonroutine nature. Intensive monitoring during the study resulted in a lower rating of symptom scores at the end of 3 months, in comparison with baseline. Participant response was favorable with regard to the IVRS. This pilot study suggested that symptom monitoring via the IVRS is feasible, has clinical usefulness in patients with cancer and heart failure, and can improve patients' satisfaction and their knowledge of how to care for themselves.

Summary

Onco-cardiology is an evolving discipline that requires the consideration of cardiotoxicity in preclinical, clinical, and therapeutic aspects of protocol development, treatment, and surveillance of patients who have undergone interventions using cardiotoxic agents. Only then can we foster new ways to maximize survival while keeping cardiac damage within acceptable limits. It is to this end that our working together has brought us to our present understanding. In the future, we may expect onco-cardiology to play an even greater role in the care of cancer patients.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Michael S. Ewer, MD, JD, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd., Houston, TX 77030

E-mail: mewer@mdanderson.org

Presented at the First International Conference on Cancer and the Heart; from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and the Texas Heart Institute at>St. Luke's Episcopal Hospital; Houston, 3–4 November 2010.

References

- 1.Von Hoff DD, Layard MW, Basa P, Davis HL Jr, Von Hoff AL, Rozencweig M, Muggia FM. Risk factors for doxorubicin-induced congestive heart failure. Ann Intern Med 1979; 91(5):710–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Ewer MS, Ali MK, Mackay B, Wallace S, Valdivieso M, Legha SS, et al. A comparison of cardiac biopsy grades and ejection fraction estimations in patients receiving Adriamycin. J Clin Oncol 1984;2(2):112–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med 2001;344(11):783–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Ewer MS, Vooletich MT, Durand JB, Woods ML, Davis JR, Valero V, et al. Reversibility of trastuzumab-related cardiotoxicity: new insights based on clinical course and response to medical treatment. J Clin Oncol 2005;23(31):7820–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Ewer MS, Lippman SM. Type II chemotherapy-related cardiac dysfunction: time to recognize a new entity. J Clin Oncol 2005;23(13):2900–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Sawyer DB, Zuppinger C, Miller TA, Eppenberger HM, Suter TM. Modulation of anthracycline-induced myofibrillar disarray in rat ventricular myocytes by neuregulin-1beta and anti-erbB2: potential mechanism for trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity. Circulation 2002;105(13):1551–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ewer MS, Ewer SM. Cardiotoxicity of anticancer treatments: what the cardiologist needs to know. Nat Rev Cardiol 2010; 7(10):564–75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Swain SM, Whaley FS, Ewer MS. Congestive heart failure in patients treated with doxorubicin: a retrospective analysis of three trials. Cancer 2003;97(11):2869–79. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Joensuu H, Bono P, Kataja V, Alanko T, Kokko R, Asola R, et al. Fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide with either docetaxel or vinorelbine, with or without trastuzumab, as adjuvant treatments of breast cancer: final results of the FinHer Trial. J Clin Oncol 2009;27(34):5685–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Vogel CL, Cobleigh MA, Tripathy D, Gutheil JC, Harris LN, Fehrenbacher L, et al. Efficacy and safety of trastuzumab as a single agent in first-line treatment of HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2002;20(3):719–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Tan-Chiu E, Yothers G, Romond E, Geyer CE Jr, Ewer M, Keefe D, et al. Assessment of cardiac dysfunction in a randomized trial comparing doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel, with or without trastuzumab as adjuvant therapy in node-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-overexpressing breast cancer: NSABP B-31. J Clin Oncol 2005;23(31):7811–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Slamon D, Eiermann W, Robert N, Pienkowski T, Martin M, Rolski J, et al. BCIRG 006 Phase III Trial comparing AC-T with AC-TH and with TCH in the adjuvant treatment of HER2-amplified early breast cancer patients: third planned efficacy analysis [monograph on the Internet]. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, 2009 [cited 2011 Mar 22]. Available at: http://www.bcirg.org/NR/rdonlyres/eno7mvfpseiqi5g3pernz37zzeavin4f7o5hos4zwlu76clvwkfluhskusgcmnqvyqk7ksb4gdimpmt6xcmkxppnqce/945_GS5_02_+abst+62+Jan+10.pdf.

- 13.Perez EA, Suman VJ, Davidson NE, Sledge GW, Kaufman PA, Hudis CA, et al. Cardiac safety analysis of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel with or without trastuzumab in the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 adjuvant breast cancer trial. J Clin Oncol 2008;26(8): 1231–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Suter TM, Procter M, van Veldhuisen DJ, Muscholl M, Bergh J, Carlomango C, et al. Trastuzumab-associated cardiac adverse effects in the herceptin adjuvant trial. J Clin Oncol 2007;25(25):3859–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.de Korte MA, de Vries EG, Lub-de Hooge MN, Jager PL, Gietema JA, van der Graaf WT, et al. 111 Indium-trastuzumab visualises myocardial human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 expression shortly after anthracycline treatment but not during heart failure: a clue to uncover the mechanisms of trastuzumab-related cardiotoxicity. Eur J Cancer 2007;43 (14):2046–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Pinder MC, Duan Z, Goodwin JS, Hortobagyi GN, Giordano SH. Congestive heart failure in older women treated with adjuvant anthracycline chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007;25(25):3808–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Jones S, Holmes FA, O'Shaughnessy J, Blum JL, Vukelja SJ, McIntyre KJ, et al. Docetaxel with cyclophosphamide is associated with an overall survival benefit compared with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide: 7-year follow-up of US Oncology Research Trial 9735. J Clin Oncol 2009;27(8): 1177–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Cardinale D, Colombo A, Lamantia G, Colombo N, Civelli M, De Giacomi G, et al. Anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy: clinical relevance and response to pharmacologic therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55(3):213–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Cardinale D, Sandri MT, Martinoni A, Tricca A, Civelli M, Lamantia G, et al. Left ventricular dysfunction predicted by early troponin I release after high-dose chemotherapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36(2):517–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Cardinale D, Sandri MT, Colombo A, Colombo N, Boeri M, Lamantia G, et al. Prognostic value of troponin I in cardiac risk stratification of cancer patients undergoing high-dose chemotherapy. Circulation 2004;109(22):2749–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Cardinale D, Colombo A, Sandri MT, Lamantia G, Colombo N, Civelli M, et al. Prevention of high-dose chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity in high-risk patients by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition. Circulation 2006; 114(23):2474–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Cardinale D, Colombo A, Torrisi R, Sandri MT, Civelli M, Salvatici M, et al. Trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity: clinical and prognostic implications of troponin I evaluation. J Clin Oncol 2010;28(25):3910–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Stewart WF, Jones JB, Paulus R, Selna N. Personalized health management: a Geisinger view [monograph on the Internet]. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services [cited 2011 Mar 22]. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/myhealthcare/news/commissioned.html.

- 24.Hunt SA, Baker DW, Chin MH, Cinquegrani MP, Feldman AM, Francis GS, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to revise the 1995 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38(7):2101–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Fadol A, Mendoza T, Gning I, Kernicki J, Symes L, Cleeland CS, Lenihan D. Psychometric testing of the MDASI-HF: a symptom assessment instrument for patients with cancer and concurrent heart failure. J Card Fail 2008;14(6):497–507. [DOI] [PubMed]