Abstract

The authors report a case of a 29-year-old male patient with a severe lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage in whom a successful laparoscopic diagnosis and resection (assisted) of an ileal gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) was performed. Laparoscopy can be very useful in the diagnosis and treatment of selected cases of lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal bleeding, Laparoscopy, Gastrointestinal stromal tumors

INTRODUCTION

The diagnosis of occult gastrointestinal bleeding of obscure origin is one of the most vexing problems confronting physicians.1 Despite impressive technological advances during the last 30 years, the management of bleeding from the lower gastrointestinal tract remains a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Although a generally accepted treatment protocol for upper gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage has been established, there is no similar consensus for the management of hemorrhage originating distal to the Treitz ligament.2

CASE REPORT

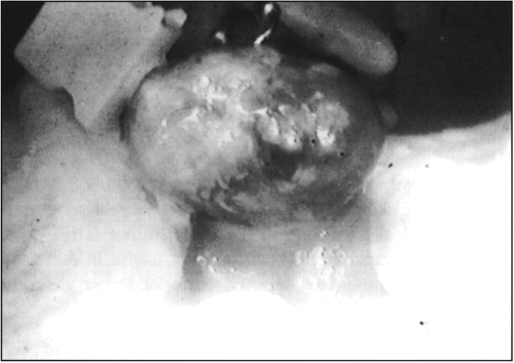

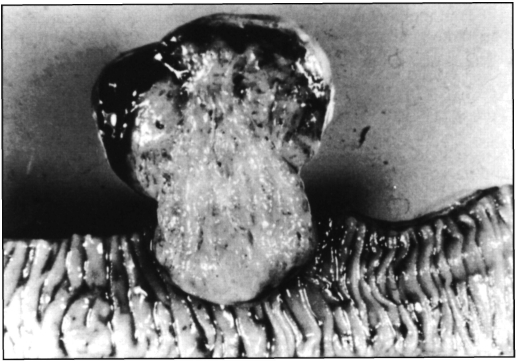

A 29-year-old white male was seen in the emergency room of the American-British Hospital of Mexico City, referred from a rural clinic in one of the neighbor states of Mexico City with a 4-day history of severe gastrointestinal bleeding characterized at first by melena and then hematochezia. Six units of packed red blood cells were transfused to the patient before his admission to the emergency room. Past history was unrewarding except for a laparoscopic fundoplication nine months before for severe gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clinical examination revealed generalized pallor and red blood on rectal digital exam. Blood pressure was 100/60 mm Hg with a pulse of 90 beats per minute. A complete blood count demonstrated a hemoglobin of 8.6 mg/1. An emergency esophagogastroduodenoscopy was negative for bleeding and showed a properly functioning fundoplication; a colonoscopy performed two hours later after bowel preparation showed fresh blood in the large bowel coming from the ileum. The next morning the patient was taken to the operating room, and, under general anesthesia, a 10 mm trocar was placed in the umbilicus. The abdominal cavity was inspected and immediately a 6 × 5 cm ileal cystic dark mass was identified in the pelvic area (Figure 1). Another 10 mm trocar was placed in the right flank and a 5 mm one in the left flank. The whole small bowel was inspected from the ligament of Treitz to the ileocecal valve and the tumor was located at 50 cm proximal to the latter. The umbilical incision was extended 3 cm downwards, the wound protected, the tumor exteriorized (Figure 2), and a 20 cm ileal resection was performed, followed by a termino-terminal stapler anastomosis. The postoperative course was uneventful: a liquid diet was tolerated the following day, a normal bowel movement occurred on postoperative day 2, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 4 and remains asymptomatic 18 months later.

Figure 1.

The cystic mass is identified in the small bowel.

Figure 2.

Exteriorized tumor.

PATHOLOGICAL EXAMINATION

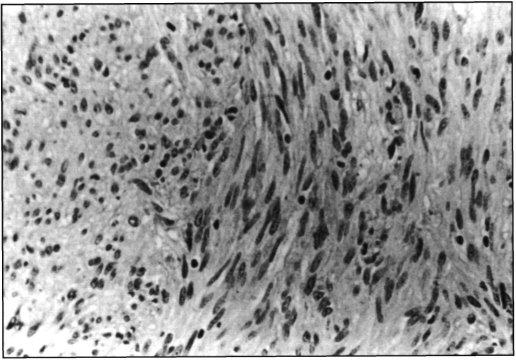

The specimen was a segment of small intestine which measured 17 × 2.5 cm. On its outer surface, a neoplasm was identified pending from the antimesenteric border. It had a reddish-brown hue, bosselated surface with areas of recent hemorrhage and measured 6 × 5.5 × 4 cm. On sectioning, it had a firm consistency, and the surface was trabeculated, gray-pink and with focal hemorrhage at the periphery. The base of implantation was 3 cm wide, and part of the neoplasia protruded through the bowel wall, creating a dumbbell shape (Figure 3). This was associated with an extensive ulcer overlying the mucosa. Microscopically, the tumor was hypercellular and made up of bundles of fusiform cells with bland nuclei, homogeneous chromatin pattern, occasional small, inconspicuous and usually single nucleolus. The cytoplasm was eosinophilic and homogeneous with unapparent cell borders. There were 2 mitotic figures in a 150 hpf count, no necrotic foci, no pleomorphic cells nor “skeinoid” fibers, and only scattered hemorrhagic areas (Figure 4). The immunohistochemical profile showed focal positivity for ps-100, CD34 (QBENd/10); actin antigen (PCNA) was strongly positive in 4.1% of neoplastic cells. DNA analysis (CAS-200) showed a hypodiploid population (DNA index: 0.4, s-phase: 3.3).

Figure 3.

Macroscopic appearance of the tumor.

Figure 4.

Microscopic appearance of the mass.

Final Pathological Diagnosis

Low risk small bowel stromal tumor (GIST), based on size (6 × 5.5 cm), no necrosis, 2 mitotic figures in hpfs and PCNA index lower than 10%.

DISCUSSION

Etiology of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding is closely associated with the patient's age. In adolescents and young adults, Meckel's diverticulum, inflammatory bowel disease and polyps account for the majority of cases. In adult patients up to 60 years of age, diverticulosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and polyps are the most common cause, whereas in patients older than 60 years angiodysplasia, diverticulosis and cancer are the most common etiologies. Most acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding episodes arise from the colon; however, 15% to 20% originate in the small intestine.2,3 It must be mentioned that the yield of small bowel series performed to evaluate patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding is 2% to 3% for small bowel tumors; use of enteroclysis, or double-contrast small bowel series, may increase the yield 6% to 10%. “Push enteroscopy” should be the next step in the evaluation of all cases of gastrointestinal bleeding of obscure origin because diagnostic yield has been reported to be that of 5% to 20% for small bowel masses. Intraoperative enteroscopy increases diagnostic yield by 20% to 30%.1 Other tests such as CT scan and endoscopic ultrasound have occasionally showed good results.3 In this case, the colonoscopy was of great importance because it gave us the information that the bleeding site was located within the limits of the jejunum and the ileum.

Following the endoscopic procedures, it was decided that the patient should be explored in the operative room given the negligible morbidity of a diagnostic laparoscopy. The rationale was that arteriography has a relatively high complication rate (up to 9%) that includes arterial thrombosis, embolization, and renal failure and success rates vary widely (14% to 72%); that radionuclide scanning is time consuming, and several reports in the literature are not encouraging3; that the bleeding site was located somewhere between the proximal jejunum and the ileum and given the patient's age the likelihood of an etiologic factor that could be readily identified by laparoscopy. Provisions were made to perform an intraoperative enteroscopy if the need was present.

Primary benign and malignant as well as metastatic neoplasms of the small bowel are rare entities, comprising less than 5% of all gastrointestinal tumors and 0.35% of all malignancies.1 Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) have been the subject of considerable debate since their earliest descriptions, with controversy centering on the cell of origin, line of cellular differentiation and the prediction of clinical behavior.4–6 It is hard to estimate the exact incidence of GIST from previous reports in the literature.5 Both benign and malignant stromal tumors may occur at any age and either sex.7

Whereas most of them are asymptomatic, the most common presenting symptom is gastrointestinal bleeding; other manifestations are obstruction, intussusception or, rarely, perforation.1,5,7 Despite advances in technology, preoperative diagnosis of GIST - specially of those in the small bowel - is often difficult and usually requires laparotomy.8 Most of these tumors are located in the stomach (47%), small bowel and rectum (11%), colon (7%), duodenum (5%) and esophagus (5%).9 Both benign and malignant tumors can share a similar appearance, even when the latter tend to be bigger than the former. From a microscopic standpoint, these neoplasms have a wide variation regarding growth patterns. There is not, however, a single immunohistochemical profile that allows one to predict the neoplasm's biological behavior. Generally accepted malignancy criteria include a diameter of more than 5 cm, invasion to nearby structures, necrosis, hypercellularity, increased nucleus/cytoplasm ratio, mitotic rate greater than 1-5 per 10 hpf, and infiltration of the overlying mucosa.5 Sometimes, the term “uncertain biological conduct” should be adopted. In these cases, evaluation of proliferative activity by immunohistochemical methods appears to be promising, though inconstant.4,10–12 The greatest value of tests using proliferative markers is the possibility to re-classify with more precision tumors that were considered as “borderline” or of “unknown biological conduct” into high or low-risk groups. Most common sites of metastasis are the liver and the peritoneum.13,14 Lymph nodes are affected in 7%-10% of cases, and rarely are extra-abdominal structures invaded: lung, subcutaneous tissue, brain, thyroid, bone, kidney, adrenals, heart, larynx, skin and spermatic cord.5 As GISTs are usually radio-resistant and insensitive to chemotherapeutic agents, the only curative therapy is surgical excision.8

It is likely that this tumor was present during the previous laparoscopic surgery, but a careful review of the video a posteriori did not reveal any abnormality during the abdominal inspection (although an examination of the small bowel was not done), and the patient did not have any evidence of anemia and/or any other gastrointestinal symptoms.

Laparoscopic surgery for small bowel obstruction, perforated diverticulitis, and for benign and malignant tumors of the small and large intestine has produced excellent results in experienced hands, although in some cases may require conversion to laparotomy and/or an assisted procedure.15–18 In the case herein presented, the tumor was localized immediately with the aid of a simple diagnostic laparoscopy, which allowed a successful assisted resection.

CONCLUSION

New applications of minimally invasive surgery are continuously being described. It is recommended that in some selected, well-evaluated patients with lower gastrointestinal bleeding of unknown origin and stable vital signs, laparoscopy may provide a precise diagnosis and adequate treatment within the same procedure, avoiding the need for time-consuming studies with substantial morbidity and expense.

Contributor Information

J. Cueto, Prof. Asist. Adj. of Surgery, LSU Medical Center, New Orleans, USA..

J. Baquera-Heredia, Department of Pathology of The American-British Cowdray Hospital, Mexico City..

References:

- 1. Bashir RM, Al-Kawas RH. Rare causes of occult small intestinal bleeding, including aortoenteric fistulas, small bowel tumors, and small bowel ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc Clin North Am. 1996;6:709–738 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murray JJ. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding. In Mazier WP, Levien DH, Luchtefeld MA, Senagore AJ, eds. Surgery of the Colon, Rectum, and Anus, ed 1. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1995:762–773 [Google Scholar]

- 3. DeMarkles MP, Murphy JR. Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Med Clin North Am. 1993;77:1085–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Franquemont DW. Differentiation and risk assessment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995;103:41–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Suster S. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Semin Diag Pathol. 1996;13:297–313 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brainard JA, Goldblum JR. Stromal tumors of the jejunum andileum. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:407–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Crawford JM. The gastrointestinal tract. In Cotran RS, Kumar V, Robbins SL, eds. Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease, ed 5. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1994:755–829 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ludwig DJ, Traverso LW. Gut stromal tumors and their clinical behavior. Am J Surg. 1997;173:390–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dougherty MJ, Compton C, Talbert M, et al. Sarcomas of the gastrointestinal tract. Separation into favorable and unfavorable prognostic group by mitotic count. Ann Surg. 1991;214:568–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hiruki T, Wolber RA, Owen DA. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen is not a useful prognostic indicator for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Mod Pathol. 1993;6:47A [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sbaschnig RJ, Cunningham RE, Sobin LH. Proliferating-cell nuclear antigen immunocytochemestry in the evaluation of gastrointestinal smooth-muscle tumors. Mod Pathol. 1994;7:7807–7883 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Franquemont DW, Frierson FH. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen immunoreactivity and prognosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Mod Pathol. 1995;8:473–477 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morgan B, Compton C, Taubert M, et al. Benign smooth muscle tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. A 24-year experience. Ann Surg. 1990;211:63–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eng-Hen Ng, Pollock RE, Romsdahl MM. Prognostic implications of patterns of failure for gastrointestinal leiomyosarcomas. Cancer. 1992;69:1334–1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jacobs M, Verdeja JC, Goldstein HS. Minimally invasive colon resection (Laparoscopic colectomy). Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1991;1:143–150 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cueto J, Rojas O, Garteiz D, Rodriguez M, Weber A. The efficacy of laparoscopic surgery in the diagnosis and treatment of peritonitis: experience with 107 cases in Mexico City. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:366–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cueto J, Melgoza C, Rojas O, Serrano F, Weber A. Laparoscopic colectomy for cancer: report of two cases. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 1994;13:409–413 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kok KY, Mathew W, Yapp SKS. Laparoscopic-assisted small bowel resection for a bleeding leiomyoma. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:995–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]