Abstract

We describe a case of a delayed liver abscess presenting two years after a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. At exploration, the patient was found to have an unretrieved gallstone as the nidus for the Streptococcus bovis abscess.

Keywords: Liver abscess, Unretrieved gallstone, Streptococcus bovis

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has become the standard procedure of choice for the treatment of gallbladder disease since its introduction in 1987. It has been demonstrated to be safe; it reduces hospital length of stay; it is cost-effective and has relatively few complications. Major complications including bile duct injury, cystic duct leak, bleeding, and bowel perforation have been extensively described in the surgical literature.1,2

Recently, the literature has described multiple complications that are less severe or life threatening; however, these complications are potentially the source of significant morbidity.3,4 Many of the complications originate from gallbladder perforations and spillage of gallstones at the time of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Despite the fact the perforation is relatively common,5 the ultimate fate and management of spilled gallstone has yet to be finalized.

CASE REPORT

The patient is a 66-year-old woman initially admitted to the medical service with fever, chills, jaundice and right upper abdominal pain. She had an ultrasound that demonstrated an enlarged common duct and stones in the gallbladder. The patient had a successful endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), sphincterotomy, and extraction of common duct stones. Gradually, her symptoms of suppurative cholangitis resolved and she underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. At surgery, an acutely inflamed gallbladder with areas of perforation was encountered. The patient was discharged in postoperative day one and was free of all symptoms.

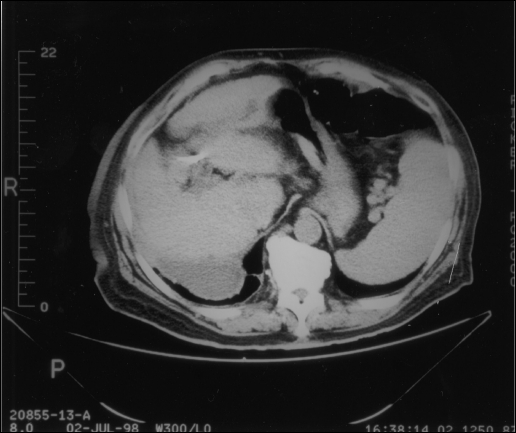

The patient remained asymptomatic for two years until she developed malaise, fever, night sweats and weight loss. She was re-admitted to the medical service, and a CT scan was obtained which showed a liver abscess. CT-guided abscess aspiration was performed that grew out Streptococcus bovis. Consultation was placed with infectious disease service, and the patient was placed on a combination of ciprofloxacin and metronidazole. Despite an eight-week course of antibiotics, the patient's symptoms persisted. A repeat CT scan showed failure of the liver abscess to be resolved (Figure 1). Consultation was also placed with the gastroenterology service. Upper and lower endoscopy was performed and were normal.

Figure 1.

CT scan showing abscess in right lobe of liver.

Six months after the initial liver abscess was diagnosed, a surgical consult was obtained. The patient was advised to have open drainage of the abscess. At laparotomy, the patient had drainage of the liver abscess and evacuation of numerous gallstones and sludge from the central portion of the abscess. She tolerated the procedure well and has remained asymptomatic one year since her laparotomy.

DISCUSSION

Gallbladder perforation is relatively common during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Most commonly, bile is spilled; however, in some cases, actual loss of gallstones occurs. Several authors have recommended that holes in the gallbladder be closed with either a suture or an endoscopic tie to avoid ongoing spillage. Gallstones should also be retrieved.

Gallstone spillage into the peritoneum most commonly occurs either during removal of the gallbladder through the umbilical port or via a hole created during liver bed dissection. Gallstone spillage occurring during gallbladder extraction can easily be prevented by careful aspiration and enlargement of the incision. Gallstone spillage during dissection from the liver bed can be prevented by meticulous dissection and repair of any holes created in the gallbladder.

This reported case is support of the proverb “to a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” Unfortunately, the patient presented to the medical service with a liver abscess and received a long, painful, costly and unsuccessful course of evaluation and treatment. The failure to relate the liver abscess to her prior laparoscopic cholecystectomy for a perforated gallbladder was the starting point of this diagnostic misadventure. The Streptococcus bovis found in the abscess cavity can be a marker for an underlying gastrointestinal malignancy necessitating the performance of colonoscopy and upper endoscopy. When a surgical consultation was finally placed, the true nature of the abscesses were appreciated, and a prompt and cost-effective definitive treatment was accomplished.

The “minor” complications associated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy can have significant major morbidity to the patient. Various delayed complications such as intraperitoneal abscess formation, viscera perforation or erosion, intestinal obstruction, adhesion, hernia and peritoneal-cutaneous sinus from unretrieved gallstones have been described. The actual rate of complications has not been accurately determined, and the fate of unretrieved gallstones is not known.6–8

Retrieval of spilled intraperitoneal gallstones should be attempted to prevent septic complications. If stones are spilled, a prolonged course of antibiotics should be considered. Liberal and early use of plastic containers and pouches can also be of benefit to reduce gallstone spillage. The question whether laparotomies should be performed in patients in whom stones cannot be retrieved or evacuated via laparoscopy has not yet been answered because of the lack of long-term follow-up and scarcity of reported complications. This case report also demonstrated the necessity for early surgical consultation to avoid a lengthy and costly delay in appropriate definitive care.

References:

- 1. Spaw AT, Reddick ES, Olsen DO. Laparoscopic laser cholecystectomy, analysis of 500 procedures. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1991;1:2–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peter JH, Ellison EC, Innes JT, et al. Safety and efficacy of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective analysis of 100 initial patients. Ann Surg. 1998;213:3–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Horton M, Florence MG. Unusual abscess patterns following dropped gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 1998;175:375–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lauffer JM, Krakenbalho L, Baer HU, et al. Clinical manifestation of lost gallstones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a case report with review of the literature. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1997;7:103–112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Soper NS, Dunnegan DL. Does intraoperative perforation influence the early outcome of laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1991;1:156–161 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Van Brunt PH, Lanzafame RJ. Subhepatic inflammatory mass after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Arch Surg. 1994;129:882–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rothlin MA, Schob O, Schlumpf R, et al. Stones spilled during cholecystectomy: a long term liability for the patient. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1997;7:432–434 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Steerman PH. Delayed peritoneal-cutaneous sinus from unretrieved gallstone. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:452–453 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]