Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Open ventral hernia repair is associated with significant morbidity and high recurrence rates. Recently, the laparoscopic approach has evolved as an attractive alternative. Our objective was to compare open with laparoscopic ventral hernia repairs.

Methods:

Fifty laparoscopic and 22 open ventral hernia repairs were included in the study. All patients underwent a tension-free repair with retromuscular placement of the prosthesis. No significant difference between the 2 groups was noted regarding patient demographics and hernia characteristics except that the population in the open group was relatively older (59.4 vs 47.82, P<0.003).

Results:

We found no significant difference in the operative time between the 2 groups (laparoscopic 132.7 min vs open 152.7 min). Laparoscopic repair was associated with a significant reduction in the postoperative narcotic requirements (27 vs 58.95 mg IV morphine, P<0.002) and the lengths of nothing by mouth (NPO) status (10 vs 55.3 hrs, P<0.001), and hospital stay (1.88 vs 5.38 days, P<0.001). The incidence of major complications (1 vs 4, P<0.028), the hernia recurrence (1 vs 4, P<0.028), and the time required for return to work (25.95 vs 47.8, P<0.036) were significantly reduced in the laparoscopic group.

Conclusions:

Laparoscopic ventral hernioplasty offers significant advantages and should be considered for repair of primary and incisional ventral hernias.

Keywords: Ventral hernia, Incisional hernia, Prosthetic inlay repair, Laparoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Incisional and primary ventral hernias represent a frequently encountered and at times frustrating problem for the general surgeon. Open repair of these hernias can be very challenging with significant associated morbidity (20% to 40%).1–2 They often (3% to 13%) complicate an otherwise uneventful abdominal operation,3 or present as an acute incarceration (6% to 15%) and strangulation (2%) mandating immediate surgical repair.4 Additionally, a significant period of hospitalization is often required for recovery. Furthermore, depending upon whether a simple suture or prosthetic repair is used, open ventral hernia repair is associated with a 46% and 23% recurrence rate, respectively.5

Recently, laparoscopic repair of ventral hernias has infused the field with new interest and enthusiasm. A literature review shows that laparoscopic ventral hernia repair has a short hospital stay (1.8 days) with acceptable complication (20%) and recurrence (4.7%) rates (Table 1).3,6–25 Five previously published studies21–25 compare the results of open and laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. These clearly demonstrate that the latter approach significantly decreases hospital stay. Unfortunately, many inconsistencies exist among these 5 studies with respect to the operative time, associated morbidity, and recurrence rate (Table 2).21–25 Moreover, significant variability exists regarding the surgical techniques in some of these studies.

Table 1.

Laparoscopic Ventral Hernia Repair: Review of 21 papers (1993 through 2000)

| No. of Patients | 10-407* | (45)† |

| Hernia Size (cm2) | 20-155* | (102)† |

| Op Time (min) | 40-210* | (95)† |

| Hospital Stay (days) | 0-4.3* | (1.8)† |

| Complications | ||

| Minor | 4.5-27.2%* | (16.5%)† |

| Major | 0-14.2%* | (2%)† |

| Total | 13-62%* | (20%)† |

| Mesh Type | ||

| Gore-Tex | 70% | |

| Marlex | 25% | |

| Prolene | 4% | |

| 1st Meal (days) | 1.8 | |

| Return to Normal Activity (days) | 15 | |

| Recurrence | 0-13%* | (4.7%)† |

| Follow-up (mos) | 7.5-51* | (21)† |

Range of mean values.

Median of mean values.

Table 2.

Laparoscopic vs Open Repair (L/O): Review of the Literature

| Study | No.(L/O) | Study Type* | Size (cm2) | Op-time (min) | Stay (days) | M&M | Recurrence | Cost ($1,000) | Follow-up (mos) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holzman21 | 21/16 | R | 105/148 | 128/97 | 1.6/4.9† | 5/5 | 2/2 | 4.3/7.2 | 20/19 |

| Park22 | 56/49 | R | 99/105 | 95/78† | 3.4/6.5† | 10/18† | 6/17 | - | 24/53† |

| Carbajo23 | 30/30 | P | 139/142 | 87/111† | 2.2/9† | 6/35 | 0/2 | - | 27/27 |

| Ramshaw24 | 79/174 | R | 73/34 | 58/82 | 1.7/2.8 | 15/26 | 2/34 | - | 21 |

| DeMaria25 | 21/18 | P | - | - | 0.8/4.4† | 13/13 | 1/1 | 8.2/12.4 | 12-24 |

R=retrospective; P=prospective.

Statistically significant difference.

The present study represents a retrospective comparative analysis of laparoscopic and open ventral hernia repairs. The 2 groups were carefully selected to match for hernia characteristics, surgical technique, and associated comorbid factors. Differences in the operative time, hospital stay, and complication and recurrence rates were investigated. Lastly, the impact of the laparoscopic approach on postoperative recovery time was evaluated for the first time by comparing the length of nothing by mouth (NPO) status, pain control, and time required to resume regular activities, including the return to work.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Characteristics and Selection Criteria

This is a retrospective review of ventral and incisional hernioplasties that were performed by the senior authors (JK and PL) between 1994 and 2000. Fifty patients underwent a laparoscopic ventral hernia repair and 22 patients an open prosthetic repair. All patients had a tension-free repair with retromuscular (extra- or intraperitoneal) placement of the prosthesis with a 2- to 4-cm overlap (inlay), resembling the Stoppa technique.26 To keep the groups as comparable as possible, all patients who underwent suture repair or prosthetic repair with the onlay, sandwich or edge-to-edge, patch-to-fascia technique were excluded from the study. Furthermore, the patients in the 2 groups were carefully selected to match, as closely as possible, for sex, age, body mass index, associated comorbid factors, and hernia characteristics (Tables 3 and 4). No significant difference between the 2 groups was noted regarding patient demographics and hernia characteristics, other than the fact that the open group consisted of a relatively older population (59.4 vs 47.82, P<0.003).

Table 3.

Patient Demographics

| Lap | Open | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 50 | 22 | |

| Age (yrs) | 47.8 | 59.4 | <0.003 |

| Sex (M/F) | 17/33 | 8/14 | NS |

| BMI (Kg/m2)* | 32.62 | 33.65 | NS |

| Patients with comorbid factors | 29 | 17 | NS |

BMI=Body mass index.

Table 4.

Hernia Characteristics

| Lap | Open | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size (cm2) | 124.6 | 201.6 | NS |

| Location | |||

| Midline | 40 | 17 | NS |

| Lateral | 10 | 5 | |

| Type | |||

| IVH* | 42 | 21 | NS |

| PVH† | 8 | 1 | |

| No. of previous repairs per patient | 1.3 | 1.3 | NS |

IVH=Incisional ventral hernia.

PVH=Primary ventral hernia.

Operative Technique

Laparoscopic access to the abdominal cavity was gained with the Veress needle, the optical trocar (Visiport™, USSC, Norwalk, CT), or the open blunt technique (Hasson type). The camera port (11 mm) and 2 or 3 working ports (5 mm) were placed as far away as possible from the hernia defect. The 0° laparoscope was used in the majority of cases, although the 30° laparoscope was available and used when significant adhesiolysis was required. Adhesiolysis was performed with laparoscopic scissors, electrocautery, or the Harmonic scalpel (USSC, Norwalk, CT). An appropriately sized mesh was placed at the subfascial plane either extraperitoneally or intraperitoneally, extending at least 2 to 4 cm beyond the edges of the defect. The Gore-Tex DualMesh (W. L. Gore & Assoc., Flagstaff, AZ) was most frequently used (62%), followed by the Composix mesh (C. R. Bard, Inc., Cranston, RI) in 28%, and the polypropylene mesh (Atrium Medical Cooperation, Hudson, NH) in 10% of patients. The polypropylene mesh was used only in situations in which we were able to dissect a sufficient flap of peritoneum to allow complete coverage of the implanted mesh, and was secured primarily with tacks (5-mm tacking device, Autosuture, USSC, Norwalk, CT). The DualMesh and the Composix mesh were secured with a minimum of 4 nonabsorbable sutures placed no more than 5 cm apart prior to intraperitoneal introduction. These sutures were then anchored transmurally with the aid of a percutaneous suture passer (reusable Carter-Thomason, Inlet Medical Inc., Eden Prairie, MN or disposable W. L. Gore & Assoc., Flagstaff, AZ). Circumferential fixation of the mesh was completed with tacks placed approximately 1.5 cm apart. All port sites larger than 5 mm were closed with sutures under laparoscopic visualization.

Open ventral hernia repair was performed according to Stoppa's technique, as previously described. Gore-Tex DualMesh (W. L. Gore & Assoc., Flagstaff, AZ) was used in 35% of the open repairs followed by Composix mesh (C. R. Bard, Inc., Cranston, RI) in 30%, polypropylene mesh (Atrium Medical Cooperation, Hudson, NH) in 30% and Vicryl mesh (Ethicon Inc., Somerville, NJ) in 5%.

Data Collection and Follow-up

Data were collected from hospital and outpatient office charts, as well as by telephone interviews. Standardized data included patient demographics, postoperative pain control, complications, recurrence, and activities. No statistically significant difference in the length of follow-up existed between the laparoscopic and open groups (20.8 and 26 months, respectively). Sixteen patients (32%) in the laparoscopic group and 6 (27.7%) in the open group were lost to follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of parametric data was performed with the 2-tailed, Student t test for unpaired variables or with the ANOVA test for more than 2 variables. The Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis test were used for categorical data with 2 or more variables, respectively. A P value of .05 or less was considered significant.

RESULTS

Five patients were excluded from the laparoscopic group because conversion to open repair was required due to adhesions (3 patients), inability to establish pneumoperitoneum (1 patient), and an ill-defined defect (1 patient).

No significant difference in the operative time was noted between the 2 groups (laparoscopic 132.7 min vs open 152.7 min). Conversely, patients who underwent open repair required significantly higher doses of narcotics than those in the laparoscopic group (58.95 vs 27 mg IV morphine, P<0.002). Similarly, the lengths of NPO status (55.3 vs 10 hrs, P<0.001) and the hospital stay (5.38 vs 1.88 days, P<0.001) were significantly longer in the patient group that underwent open repair (Table 5).

Table 5.

Postoperative Results

| Lap | Open | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operative time (min) | 132.7 | 152.7 | NS |

| Pain control (mg iv morphine) | 27 | 58.95 | <0.002 |

| Length of NPO status (hrs)* | 10 | 55.38 | <0.001 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 1.88 | 5.38 | <0.001 |

NPO=nothing by mouth.

The incidence of major complications was significantly higher in the open group (4 vs 1, P<0.028). One postoperative death occurred due to respiratory failure in the open repair group. Also occurring in this group were a postoperative small bowel obstruction that resolved with conservative management, a splenic abscess, and a case of pulmonary embolism that responded to heparin therapy. One laparoscopic hernioplasty was complicated by a postoperative complex hematoma that eventually required removal of the prosthesis (Table 6).

Table 6.

Postoperative Complications

| Lap | Open | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minor | 13 | 6 | NS |

| Major | 1 | 4 | <0.028 |

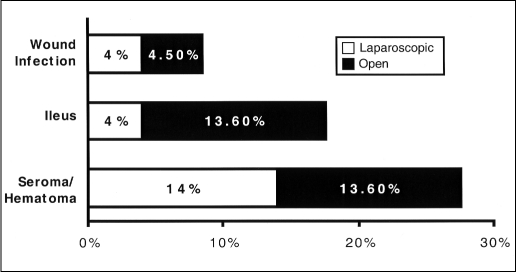

On the contrary, no significant difference between the 2 groups was noted in the incidence of minor complications. It is of interest that the incidence of postoperative ileus was higher in the open group (13.6% vs 4%), even though it did not reach a statistically significant difference. The likelihood of wound infection and seroma formation was similar in the 2 groups (Figure 1). All seromas resolved spontaneously without requiring percutaneous needle aspiration.

Figure 1.

Minor complications.

During follow-up, 4 (18.2%) patients in the open repair group developed a recurrence compared with only 1 (2%) patient in the laparoscopic group, which had recurred after removal of the prosthesis. Our results revealed a significant reduction in the recovery time for patients in the laparoscopic group. They returned to work earlier and resumed regular activities more rapidly (Table 7).

Table 7.

Follow-up Results

| Lap | Open | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Return to regular activities (days) | 21.1 | 33.75 | NS |

| Return to work (days) | 25.95 | 47.8 | <0.036 |

| Hernia recurrence | 1 | 4 | <0.028 |

DISCUSSION

Obviously, a concern exists about selection bias in our study, because of the retrospective nature of the data analysis. To maintain the validity of our results, certain inclusion criteria were used in patient selection. The technique used for inclusion for all ventral hernioplasties included (laparoscopic and open) resembled the tensionfree, inlay prosthetic repair described by Rives, Stoppa and Wantz. In contrast to 3 previous comparative studies,21,24,25 primary suture repair and onlay mesh placement were excluded from our study because they are dissimilar to the laparoscopic technique and are also associated with higher recurrence rates.5,27

Furthermore, particular attention was given to the demographic profile and the hernia characteristics, which were relatively similar in both groups (Tables 3 and 4). Considering the importance of proper terminology in ventral hernias (primary, incisional, or recurrent incisional), as this reflects upon the outcome and associated morbidity of the repair,6 we discovered no difference in their incidence between the 2 groups (Table 4). Lastly, a special effort was made to include only patients from a specific period (1994 to 2000) to achieve a similar length of follow-up for all patients. We believe that significant differences in the length of follow-up between the 2 groups, as in a previous comparison study by Park et al,22 can reflect differences in the level of the surgeon's experience, choice of repair, and quality of perioperative care, which ultimately may weaken the results and not allow for a statistical comparison of recurrence rates.

Nevertheless, our study confirms previous reports demonstrating that laparoscopic ventral hernia repair significantly shortens hospital stay (Table 2).21–25 On the other hand, we found that the laparoscopic approach does not prolong operative time, as previously suggested.22 Although, in our study the overall complication rate was not different between the 2 groups, interestingly we observed a significant decrease in the incidence of major postoperative complications. Our study is also the first to produce statistically supporting evidence for an existing significant difference in the recurrence rate in favor of the laparoscopic group.

The only published, prospectively randomized study comparing the open and the laparoscopic repair of ventral hernias is that by Carbajo's group.23 Congruent to our results, Carbajo et al demonstrated that the laparoscopic approach decreases the incidence of complications and hernia recurrence. However, other parameters, such as postoperative pain control and length of recovery, were not evaluated in his trial. Our study is the first to validate the presumption that the laparoscopic approach does indeed significantly improve the patient's postoperative comfort and allows faster recovery. Furthermore, we show that laparoscopic repair is associated with earlier return to work and regular activities. Without a doubt, this observation is expected to positively affect the burden on financial and human resources that results from temporary disability, including days off from work, after ventral hernia repair.

Clearly, laparoscopic ventral hernioplasty offers significant advantages over the open approach. It provides better visualization of the hernia defect, leading to a more adequate repair, which probably explains the associated lower recurrence rate. Also, by significantly shortening the hospital stay and to a lesser extent the operative time, it decreases the overall health care costs counterbalancing and most likely offsetting the higher equipment costs. The faster recovery time, the markedly improved postoperative patient comfort and the reduced complication rate observed with the laparoscopic approach will entirely change the concept of the “frustrating problem” and the significant morbidity that surgeons often encounter with ventral hernia repair.

CONCLUSION

Based on these data, the laparoscopic approach is an attractive alternative and should be considered for the repair of primary and incisional ventral hernias.

Contributor Information

Ioannis Raftopoulos, Metropolitan Group Hospitals General Surgery Residency Program at Chicago, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA..

Daniel Vanuno, Department of Surgery, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA..

Jubin Khorsand, Department of Surgery, Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Illinois, USA..

Gregory Kouraklis, 2nd Department of Surgery, Laiko Hospital, University of Athens, Athens, Greece..

Philip Lasky, Department of Surgery, Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA..

References:

- 1. Leber GE, Garb JL, Alexander AI, Reed WP. Long-term complications associated with prosthetic repair of incisional hernias. Arch Surg. 1998;133:378–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anthony T, Bergen PC, Lawrence TK, et al. Factors affecting recurrence following incisional herniorrhaphy. World J Surg. 2000;24:95–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Costanza MJ, Heniford BT, Arca MJ, Gagner M. Laparoscopic repair of recurrent ventral hernias. Am Surg. 1998;64(12): 1121–1127 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Read RC, Yoder G. Recent trends in the management of incisional herniation. Arch Surg. 1989;124:485–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Luijendijk RW, Hop WCJ, Van Den Tol MP, et al. A comparison of suture repair with mesh repair for incisional hernia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:392–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koehler RH, Voeller G. Recurrences in laparoscopic incisional hernia repairs: A personal series and review of the literature. JSLS. 1999;3:293–304 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heniford BT, Ramshaw BJ. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. A report of 100 consecutive cases. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:419–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heniford BT, Park A, Ramshaw BJ, Voeller G. Laparoscopic ventral and incisional hernia repair of 407 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190(6):645–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Toy FK, Bailey RW, Carey S, et al. Prospective, multicenter study of laparoscopic ventral hernioplasty: preliminary results. Surg Endosc. 1998;12(7):955–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. LeBlanc KA. Current considerations in laparoscopic incisional and ventral herniorrhaphy. JSLS. 2000;4(2):131–139 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Park A, Gagner M, Pomp A. Laparoscopic repair of large incisional hernias. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1996;6:123–128 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Franklin ME, Dorman JP, Glass JL, Balli JE, Gonzalez JJ. Laparoscopic ventral and incisional hernia repair. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1998;8(4):294–299 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tsimoyiannis EC, Tassis A, Glantzounis G, Jabarin M, Siakas P, Tzourou H. Laparoscopic intraperitoneal onlay mesh repair of incisional hernia. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1998;8(5):360–362 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Szymanski J, Voitk A, Joffe J, Alvarez C, Rosenthal G. Technique and early results of outpatient laparoscopic mesh onlay repair of ventral hernias. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:582–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saiz AA, Willis IH, Paul DK, Sivina M. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair: a community hospital experience. Am Surg. 1996;62:336–338 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sanders LM, Flint LM. Initial experience with laparoscopic repair of incisional hernias. Am J Surg. 1999;177:227–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chowbey PK, Sharma A, Khullar R, Mann V, Baijal M, Vashistha A. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2000;10(2):79–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reitter DR, Paulsen JK, Debord JR, Estes NC. Five-year experience with the “Four-before” laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Am Surg. 2000;66:465–469 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kyzer S, Alis M, Aloni Y, Charuzi I. Laparoscopic repair of postoperation ventral hernia. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:928–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Frantzides CT, Carlson MA. Minimally invasive herniorrhaphy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 1997;7(2):117–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Holzman MD, Purut CM, Reintgen K, Eubanks S, Pappas TN. Laparoscopic ventral and incisional hernioplasty. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:32–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Park A, Birch DW, Lovrics P. Laparoscopic and open incisional hernia repair: A comparison study. Surgery. 1998;124(4): 816–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carbajo MA, del Olmo JCM, Blanco JI, et al. Laparoscopic treatment vs open surgery in the solution of major incisional and abdominal wall hernias with mesh. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:250–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ramshaw BJ, Esartia P, Schwab J, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic and open ventral herniorrhaphy. Am Surg. 1999;65:827–832 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. DeMaria EJ, Moss JM, Sugerman HJ. Laparoscopic intraperitoneal polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) prosthetic patch repair of ventral hernia. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:326–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stoppa RE. The treatment of complicated groin and incisional hernias. World J Surg. 1989;13:545–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heniford T, Park A, Voeller G. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Surg Prospectus. 1999;1:1–11 [Google Scholar]