Abstract

Congenital cataracts (CCs), responsible for about one-third of blindness in infants, are a major cause of vision loss in children worldwide. Autosomal-recessive congenital cataracts (arCC) form a clinically diverse and genetically heterogeneous group of disorders of the crystalline lens. To identify the genetic cause of arCC in consanguineous Pakistani families, we performed genome-wide linkage analysis and fine mapping and identified linkage to 3p21-p22 with a summed LOD score of 33.42. Mutations in the gene encoding FYVE and coiled-coil domain containing 1 (FYCO1), a PI(3)P-binding protein family member that is associated with the exterior of autophagosomes and mediates microtubule plus-end-directed vesicle transport, were identified in 12 Pakistani families and one Arab Israeli family in which arCC had previously been mapped to the overlapping CATC2 region. Nine different mutations were identified, including c.3755 delC (p.Ala1252AspfsX71), c.3858_3862dupGGAAT (p.Leu1288TrpfsX37), c.1045 C>T (p.Gln349X), c.2206C>T (p.Gln736X), c.2761C>T (p.Arg921X), c.2830C>T (p.Arg944X), c.3150+1 G>T, c.4127T>C (p.Leu1376Pro), and c.1546C>T (p.Gln516X). Fyco1 is expressed in the mouse embryonic and adult lens and peaks at P12d. Expressed mutant proteins p.Leu1288TrpfsX37 and p.Gln736X are truncated on immunoblots. Wild-type and p.L1376P FYCO1, the only missense mutant identified, migrate at the expected molecular mass. Both wild-type and p. Leu1376Pro FYCO1 proteins expressed in human lens epithelial cells partially colocalize to microtubules and are found adjacent to Golgi, but they primarily colocalize to autophagosomes. Thus, FYCO1 is involved in lens development and transparency in humans, and mutations in this gene are one of the most common causes of arCC in the Pakistani population.

Main Text

A significant cause of vision loss worldwide, congenital cataracts (CC) cause approximately one-third of the cases of blindness in infants.1 They can occur in an isolated fashion or as one component of a syndrome affecting multiple tissues, although the distinction might be somewhat arbitrary in some cases. In approximately 70% of CC cases, the lens alone is involved.2 Nonsyndromic CCs have an estimated frequency of 1–6 per 10,000 live births,3 and approximately one-third of CC cases are familial.4 Congenital cataracts are very heterogeneous, both clinically and genetically, and approximately 8.3%–25% of nonsyndromic CCs are inherited as an autosomal-recessive (ar), autosomal-dominant (ad), or X-linked trait.5–7 To date, more than 40 loci for human CCs have been identified, and more than 26 of them have been associated with causative mutations in specific genes.8 To date, 14 genetic loci have been implicated in nonsyndromic autosomal-recessive CC (arCC), and most of these account for a few percentage points of CC cases each. Among these loci, mutations in nine genes, eph-receptor type-A2 (EPHA2, MIM 613020), connexin50 (GJA8, MIM 600897), glucosaminyl (N-acetyl) transferase 2 (GCNT2, MIM 600429), heat-shock transcription factor 4 (HSF4, MIM 602438), lens intrinsic membrane protein (LIM2, MIM, 154045), beaded filament structural protein 1 (BFSP1, MIM 603307), αA-crystallin (CRYAA, MIM 123580), βB1-crystallin (CRYBB1, MIM 600929), and βB3-crystallin (CRYBB3, MIM 123630), have been found.9–18 In six of the 14 reported arCC loci, the mutated gene is as yet unknown. The CATC2 (Cataract, Autosomal Recessive Congenital 2, MIM 610019) locus was first mapped to chromosome 3 in three inbred Arab families in 2001, but the disease-associated variants previously had not been identified.19

As part of an ongoing collaboration between the National Eye Institute (NEI, Bethesda, MD, USA), the National Centre of Excellence in Molecular Biology (NCEMB, Lahore, Pakistan), and Allama Iqbal Medical College (Lahore, Pakistan), a locus for arCC in twelve Pakistani families has been mapped to chromosomal region 3p21-p22, overlapping the CATC2 locus.19 Subsequently, homozygous missense, splice site, nonsense, and frameshift mutations have been identified in a positional candidate gene, FYCO1 (FYVE and coiled-coil domain containing 1 [MIM 607182]). In addition, a nonsense mutation was found in an Arab Israeli family in which the CATC2 locus had been mapped. In total, 9 FYCO1 mutations were identified in 13 arCC families, including 44 affected individuals, in which arCC segregates with the mutant FYCO1 allele, underlining the importance of FYCO1 in both lens biology and the pathogenesis of arCC.

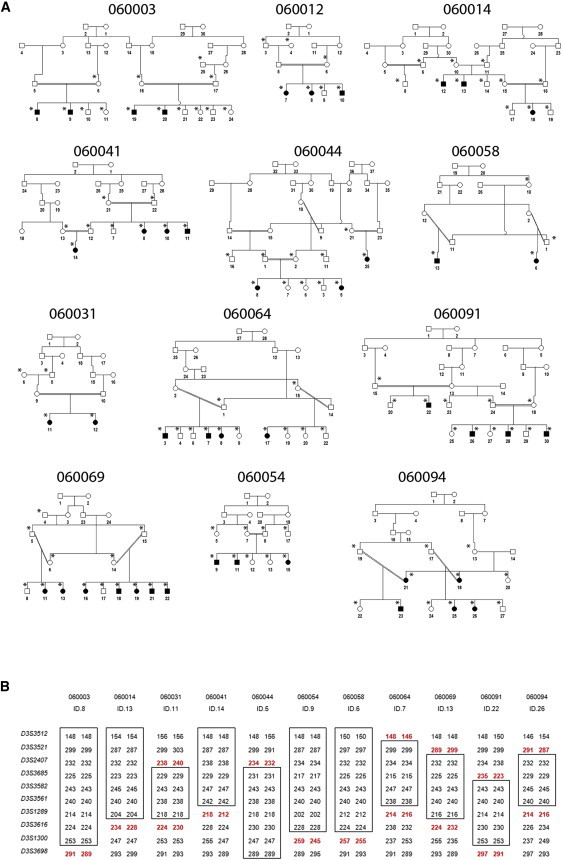

In this study, genome-wide linkage scans and fine mapping were performed in eight unrelated consanguineous arCC families of Pakistani origin, and 63 additional unlinked consanguineous families of Pakistani origin were additionally screened for mutations in FYCO1. Families described in this study include 060003 (also referred to as PKCC003), 060012 (PKCC012), 060014 (PKCC014), 060031 (PKCC031), 060041 (PKCC041), 060044 (PKCC044), 060054 (PKCC054), 060058 (PKCC058), 060064 (PKCC064), 060069 (PKCC069), 060091 (PKCC091), and 060094 (PKCC094). This study was approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the National Centre of Excellence in Molecular Biology and the CNS IRB at the National Institutes of Health. Participating subjects gave informed consent consistent with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ophthalmological examinations were performed at the Layton Rahmatullah Benevolent Trust Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan. A detailed medical history was obtained by interviewing family members. Medical records of clinical exams conducted with slit lamp biomicroscopy reported the types of cataract in affected individuals of the twelve families. We also recruited 150 unrelated, ethnically matched individuals, who provided control DNA samples. Blood samples were obtained from study participants and DNA was extracted using standard inorganic methods as previously described.20 All affected individuals available for examination from twelve consanguineous Pakistani arCC families (060003, 060012, 060014, 060031, 060041, 060044, 060054, 060058, 060064, 060069, 060091, and 060094) displayed bilateral nuclear cataracts that either were present at birth or developed in infancy (Figure 1). Some affected individuals had undergone cataract surgery in the early years of life, and hence no pictures of their lenses were available. Autosomal recessive inheritance of the cataracts was seen in all families (Figure 2A). No other ocular or systemic abnormalities were present in these families.

Figure 1.

Slit-Lamp Photograph of a Cataract Patient with FYCO1 Mutations

A slit-lamp photograph of affected individual 19 of family 060069 shows a nuclear cataract that developed in early infancy.

Figure 2.

Pedigrees and Linkage Intervals for arCC Families

(A) Twelve arCC pedigrees collected from Pakistan. Filled symbols denote affected individuals. Eight pedigrees (060003, 060012, 060041, 060058, 060064, 060069, 060091, and 060094) were used for genome-wide linkage scans and fine mapping of arCC intervals and candidate-gene mutation screenings. Four pedigrees (060014, 060031, 060044, and 060054) were used for fine mapping of arCC intervals and candidate-gene mutation screenings. Individuals who were genotyped are marked with an asterisk.

(B) Refined arCC interval on the basis of haplotype analysis of patients with recombination events. Markers with the homozygous genotype are boxed so that the region without recombination is defined. Alleles for markers D3S3685 and D3S1289 in patients with recombination events are in bold so that the telomeric and centromeric breakpoints, respectively, are shown. The disease interval was placed between markers D3S3685 and D3S1289.

Genome-wide linkage analysis was completed with 382 highly polymorphic microsatellite markers from the ABI PRISM Linkage Mapping Set MD-10 (Figure S2, available online; average spacing 10 cM; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). PCR products were separated on an ABI 3130 DNA Analyzer, and alleles were assigned with GeneMapper Software version 4.0 (Applied Biosystems). Two-point linkage analyses were performed with the FASTLINK version of MLINK from the LINKAGE Program Package.21,22 Maximum LOD scores were calculated with ILINK. Autosomal-recessive cataracts were analyzed as a fully penetrant trait with a disease allele frequency of 0.001, and equal allele frequencies were arbitrarily used for all markers in the genome-wide scan. Marker allele frequencies were calculated from 100 Pakistani control individuals for fine mapping (Table S3). The marker order and distances between the markers were obtained from the Marshfield database and the NCBI chromosome 3 sequence maps (see Table S1). Eight of these families (060003, 060012, 060041, 060058, 060064, 060069, 060091, and 060094) independently showed significant or suggestive linkage to chromosomal region 3p21-p22; LOD scores were 3.85, 2.52, 4.09, 2.36, 3.89, 5.62, 4.88, and 3.82, respectively.

Sequencing of candidate genes (see below) identified FYCO1 mutations in affected members of these eight families and subsequently in four additional arCC families (see below). Two-point linkage analysis in the 12 families with FYCO1 mutations confirms linkage to a 7.4 cM (15.6 Mb) region flanked by D3S3521 and D3S1289 (Table 1). The linked region includes markers D3S3582 (Zmax = 33.4 at θ = 0), D3S3561 (Zmax = 22.4 at θ = 0), D3S3685 (Zmax = 33.5 at θ = 0.01), and D3S2407 (Zmax = 24 at θ = 0.03). Significant LOD scores were also seen with other markers in the region, including D3S3512 (Zmax = 16.75 at θ = 0.08), D3S3521 (Zmax = 18.15 at θ = 0.05), D3S1289 (Zmax = 25.86 at θ = 0.02), D3S3616 (Zmax = 20.14 at θ = 0.05), D3S1300 (Zmax = 14.29 at θ = 0.09), and D3S3698 (Zmax = 2.14 at θ = 0.2), although these markers show obligate recombination events. Haplotype analysis confirmed and narrowed the critical interval (Figure 2B and Figure S1). Key recombination events were detected between markers D3S3582 and the adjacent telomeric marker D3S3685 in affected individuals 22, 26, 28, and 30 of family 060091 (Figure 2B and Figure S1), so that D3S3685 defines the telomeric boundary for the 3.5 cM (12 Mb) disease interval. Similarly, recombination events were detected between marker D3S3561 and its adjacent centromeric marker D3S1289 in individual 14 of family 060041, individuals 3, 7, and 8 of family 060064, and individual 26 of 060094 (Figure 2B and Figure S1), so that D3S1289 is the centromeric flanking marker. Thus, arCC in each of these 12 families cosegregates with a chromosome 3 region that includes FYCO1.

Table 1.

Two-Point LOD Scores of Markers on Chromosomal Region 3p21 in a Total of 12 arCC Families

| Marker | cM | Mb | 0 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | Zmax | θmax |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D3S3512 | 61.52 | 34.59 | - ∞ | 12.29 | 16.28 | 16.64 | 13.85 | 9.42 | 4.56 | 16.75 | 0.08 |

| D3S3521 | 63.12 | 38.87 | - ∞ | 15.69 | 18.15 | 17.21 | 13.1 | 8.2 | 3.5 | 18.15 | 0.05 |

| D3S2407 | 67.94 | 41.39 | 16.94 | 23.58 | 23.63 | 21.72 | 16.55 | 10.74 | 4.98 | 24.02 | 0.03 |

| D3S3685 | 67.94 | 42.47 | 32.7 | 33.5 | 31.4 | 28.09 | 20.87 | 13.32 | 6.07 | 33.5 | 0.01 |

| D3S3582 | 69.19 | 45.39 | 33.42 | 32.77 | 30.14 | 26.74 | 19.63 | 12.36 | 5.54 | 33.42 | 0 |

| D3S3561 | 70.61 | 52.34 | 22.37 | 21.88 | 19.9 | 17.4 | 12.35 | 7.43 | 3.09 | 22.37 | 0 |

| D3S1289∗ | 71.41 | 54.48 | - ∞ | 25.62 | 25.05 | 22.56 | 16.45 | 9.93 | 3.99 | 25.86 | 0.02 |

| D3S3616 | 76.48 | 57.34 | - ∞ | 17.11 | 20.14 | 19.28 | 14.79 | 9.15 | 3.94 | 20.14 | 0.05 |

| D3S1300∗ | 80.32 | 60.51 | - ∞ | 7.01 | 13.46 | 14.25 | 11. 8 | 7.75 | 3.54 | 14.29 | 0.09 |

| D3S3698 | 84.92 | 63.12 | - ∞ | −17.66 | −4.57 | −0.21 | 2.14 | 1.93 | 0.99 | 2.14 | 0.2 |

An asterisk indicates that an STR marker was included in the genome-wide scan.

The linked region on chromosome 3 contains 287 genes or potential genes, according to the UCSC database. Candidate genes were prioritized on the basis of their expression in the lens and possible function in lens biology and transparency, as indicated in the NCBI and GeneCard databases. Although no candidate genes were absolutely excluded, pseudogenes, genes of unknown function and without known domain structures, and genes not expressed in the lens were given the lowest priorities. Primer pairs for individual exons in the critical interval were designed with the online primer3 program. The sequences and amplification conditions for FYCO1 primers are available in Table S2. The PCR primers for each exon were used for bidirectional sequencing with Big Dye Terminator Ready reaction mix according to instructions of the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Sequencing was performed on an ABI PRISM 3130 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Sequence traces were analyzed with Mutation Surveyor (Soft Genetics Inc., State College PA) and the Seqman program of DNASTAR Software (DNASTAR Inc, Madison, WI, USA).

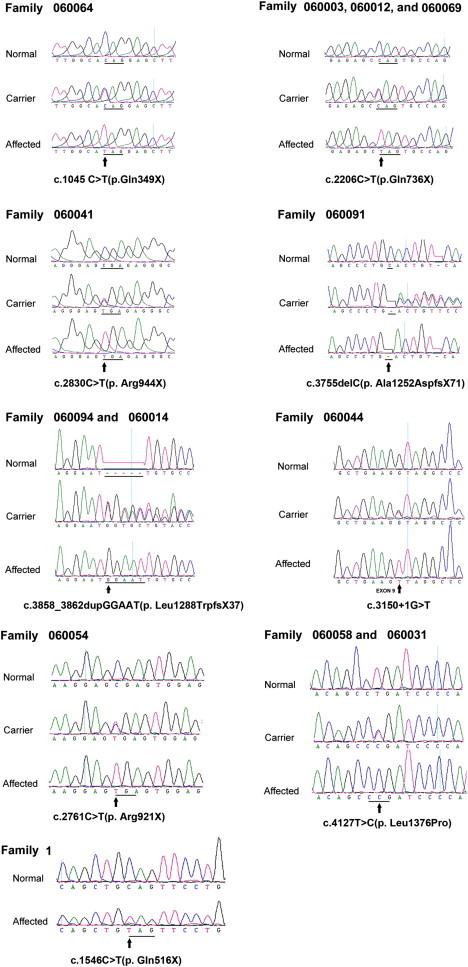

After family 060064 was screened for 35 genes in the linked region (all of these genes were found to lack pathogenic mutations), the FYVE and coiled-coil domain containing 1 (FYCO1) gene was sequenced, and mutations were identified in this family and subsequently in the remaining seven linked families (NM_024513.2, Table 2 and Figure 3). Mutations were confirmed in all available affected family members. In family 060064, the affected individuals carry a homozygous C>T transition (1045 C>T) in exon 8, which results in a premature termination of translation (p.Gln349X). Three families (060003, 060012, and 060069) share a homozygous C>T transition (2206 C>T) in exon 8, and this transition results in a putative premature termination of translation or nonsense-mediated decay (p.Gln736X). These families share a common haplotype of 14 consecutive SNP markers across FYCO1, suggesting that they derive the mutant allele from a common ancestor (Table 3). In family 060041, a homozygous single base change in exon 8 converts an arginine residue to a premature stop codon (c.2830C>T; p.Arg944X). In family 060091, a homozygous single base-pair deletion in exon 13 causes a frameshift (c.3755 delC, p.Ala1252AspfsX71) resulting in a putative stop codon 71 amino acids downstream. In family 060094, affected individuals carry a homozygous 5 bp exon 14 duplication causing a frameshift (c.3858_3862dupGGAAT, p.Leu1288TrpfsX37) and putative stop codon 37 amino acids downstream. In family 060058, affected individuals carry a homozygous single base change converting a leucine to a proline residue in exon 16 (c.4127T>C; p.Leu1376Pro).

Table 2.

FYCO1 Mutations in 13 arCC Families

| Family | Allele Sharing | Maximum LOD Score | Exon | Nucleotide Change | Predicted Amino Acid Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 060064 | no | 3.89 | 8 | c.1045 C>T | p.Gln349X |

| 060003 | yes | 3.85 | 8 | c.2206C>T | p.Gln736X |

| 060012 | yes | 2.52 | 8 | c.2206C>T | p.Gln736X |

| 060069 | yes | 5.62 | 8 | c.2206C>T | p.Gln736X |

| 060054 | no | 2.61 | 8 | c.2761C>Ta | p.Arg921X |

| 060041 | no | 4.09 | 8 | c.2830C>Ta | p.Arg944X |

| 060044 | no | 2.53 | 9 | c.3150+1 G>T | inactivation of splice donor site |

| 060091 | no | 4.88 | 13 | c.3755 delC | p.Ala1252AspfsX71 |

| 060094 | yes | 3.82 | 14 | c.3858_3862dupGGAAT | p.Leu1288TrpfsX37 |

| 060014 | yes | 2.73 | 14 | c.3858_3862dupGGAAT | p.Leu1288TrpfsX37 |

| 060058 | yes | 2.36 | 16 | c.4127T>C | p.Leu1376Pro |

| 060031 | yes | 2.28 | 16 | c.4127T>C | p.Leu1376Pro |

| Family 119 | no | n/a | 8 | c.1546C>T | p.Gln516X |

Nucleotide and amino acid designations are based on Refseq NM_024513.2.

These C>T changes occurred in a CpG dinucleotide.

Figure 3.

Sequence Electropherograms of the Eight Homozygous Mutations Found in FYCO1 and Associated with arCC

Wild-type sequence from normal control individuals is shown in the top panel for comparison. The c.1045C>T (p.Gln349X), c.1546C>T (p.Gln516X)), c.2206C>T (p.Gln736X), c.2761C>T (p. Arg921X), and c.2830C>T (p. Arg944X) mutations result in the generation of a stop codon; the c.3755 delC (Ala1252AspfsX71) and c.3858_3862dupGGAAT (p.Leu1288TrpfsX37) mutations lead to a frameshift and a premature termination of translation; the c. 3150+1 G>T mutation leads to elimination of the intron 9 donor site; and the c.4127T>C (p.Leu1376Pro) mutation results in the change of a leucine residue to a proline residue in exon 16.

Table 3.

Intragenic FYCO1 Haplotypes of Families Sharing Common Mutations

|

p.Gln736X |

p.Leu1288TrpfsX37 |

p.Leu1376Pro |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR Amplicon | Position | SNP ID | Allele (Frequency) | Family 060003 | Family 060012 | Family 060069 | Family 060094 | Family 060014 | Family 060031 | Family 060058 |

| 4 | 45961218 | rs4682801 | C(.07)/A(.93) | A | A | A | A | A | A | A |

| 5 | 45956851 | rs751552 | T(.71)/A(.29) | T | T | T | A | A | T | T |

| 6 | 45954545 | rs41289622 | A(.61)/C(.39) | C | C | C | A | A | A | A |

| 8A | 45950077 | rs4683158 | G(.07)/A(.93) | A | A | A | A | A | A | A |

| 8A | 45950007 | rs13071283 | A(.61)/G(.39) | G | G | G | A | A | A | A |

| 8B | 45949864 | rs3733100 | G(.56)/C(.44) | C | C | C | C | C | G | G |

| 8C | 45949487 | rs33910087 | C(.67)/T(.33) | T | T | T | C | C | C | C |

| 8E | 45948790 | rs3796375 | C((.73)/T(.27) | C | C | C | T | T | C | C |

| 8G | 45948087 | rs13079869 | C(.7)/T(.3) | T | T | T | C | C | C | C |

| 8H | 45947825 | rs71622515 | AAC(.61)/GAA(.39) | GAA | GAA | GAA | AAC | AAC | AAC | AAC |

| 8H | 45947702 | rs1994490 | A(.39)/G(.61) | G | G | G | G | G | A | A |

| 12 | 45940870 | rs13069079 | C(.61)/T(.39) | T | T | T | C | C | C | C |

| 14 | 45936761 | rs1463680 | C(.18)/T(.82) | T | T | T | T | T | T | T |

| 15 | 45917899 | rs1873002 | A(.16)/G(.84) | G | G | G | G | G | G | G |

| Fia | .00019 | .00019 | .00019 | .000813 | .000813 | .00162 | .00162 | |||

| FHCHMb | 0.019 | 0.019 | 0.019 | 0.026 | 0.026 | 0.037 | 0.037 | |||

The PCR amplicon, as well as the SNP, its position in the Ref_Assembly Build 37.1, SNP ID, and allelic variants are shown. Haplotypes were constructed on the basis of 14 consecutive intragenic single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within FYCO1.

Fi: Frequency of the haplotype calculated on an assumption of independent inheritance of all SNP alleles estimated from 48 unrelated Pakistani controls.

FHCHM: Frequency of the haplotype calculated from 48 unrelated Pakistani controls via the CHM algorithm as implemented in the Golden Helix SVS package.

Linkage analysis in some of the 125 arCC families ascertained had mapped loci to regions other than 3p21-p22. Sequencing FYCO1 in an affected individual from each of the 63 families in whom linkage analysis had not yielded a maximal LOD score of 3 identified mutations in four additional families (Table 2 and Figure 3). In family 060054, a homozygous single base change in exon 8 converts an arginine residue to a premature stop codon (c.2761C>T; p.Arg921X). In family 060044, we identified a homozygous single base change, a G-to-T transversion located in the conserved intron 9 donor splice site (c. 3150+1 G>T), suggesting that it might affect splicing. This is supported by the calculated splice-site scores of 7.6 for the normal splice site and −3.2 for the variant site, predicting that the c. 3150+1 G>T change leads to elimination of the intron 9 donor site. As in family 060094, exon 14 of affected individuals in family 060014 contains a homozygous 5 bp duplication causing a frameshift. The families share a common 14 intragenic FYCO1 SNP haplotype, suggesting that the mutant allele originates from a common ancestor (Table 3). As in family 060058, exon 16 of affected individuals in family 060031 contains a homozygous single base change that converts a leucine residue to a proline residue (c.4127T>C; p.Leu1376Pro). Once more, these two families share a common 14 SNP intragenic FYCO1 haplotype, suggesting that the disease allele originates from a common ancestor (Table 3). Each of the identified mutations segregates with arCC in the families, and none is present in the NCBI or Ensemble SNP databases. In addition, none of these eight mutations was detected in 300 unrelated, ethnically matched control chromosomes or in HapMap samples of any ethnicity. In addition, FYCO1 was sequenced in family 1 from Pras et al.,19 and the finding of a homozygous c.1546C>T sequence change (p.Gln516X) indicates that the FYCO1 mutation causes the autosomal-recessive congenital cataracts in this consanguineous Arabic family (Figure 3) and thus is the gene mutated in CATC2.

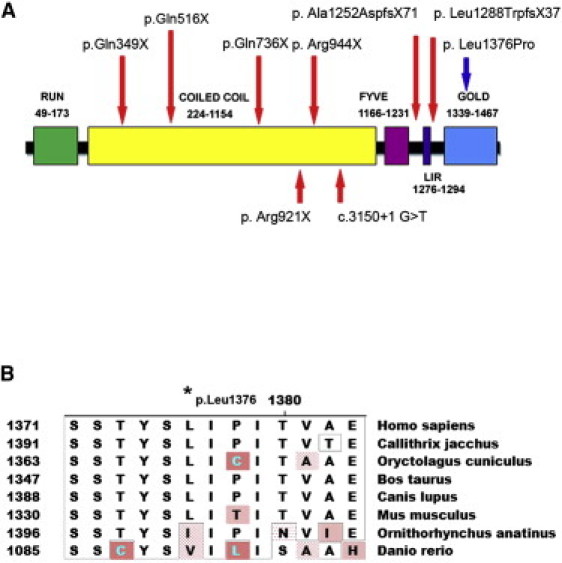

FYCO1 on chromosome 3 contains 18 exons comprising 79 Kb and encoding 1478 amino acids.23,24 The full-length FYCO1 mRNA (NM_024513.2) encodes a 167 kDa protein. FYCO1 has been highly conserved throughout evolution (protein sequence identity between humans and dogs after alignment via the CLUSTALW algorithm is 81%; that between humans and cows is 81%, that between humans and mice is 78%, that between humans and platypuses is 66%, and that between humans and zebrafish is 37%). Analyses using the Conserved Domain Database25 and the COILS web server26 predict that FYCO1 is a long coiled-coil protein similar to members of two families of Rab effector proteins: RUN and FYVE domain-containing proteins (RUFY1–4) and early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1).27 FYCO1 contains a long central coiled-coil region flanked at the N terminus by an α-helical RUN domain or a zinc finger domain and at the C terminus by a FYVE domain (Figure 4A). Unique to FYCO1 is the presence of a C-terminal extension in the form of a GOLD (Golgi dynamics) domain and an unstructured loop region connecting the FYVE and GOLD domains (Figure 4A). Most of the identified mutations truncate the protein and are predicted to cause termination of the peptide chain before the GOLD domain structure is formed and so to result in loss of activity. In addition, these truncation mutations occur in internal exons, making these mRNAs potential targets for nonsense-mediated decay.

Figure 4.

FYCO1 Domain Structure and Mutations

(A) Schematic diagram of FYCO1, showing the locations and effects of the recessive mutations. Domain structure of FYCO1. FYVE represents the FYVE zinc-finger domain; LIR represents the LC3-interacting region; and GOLD represents the Golgi dynamics domain. Red arrows show the positions of the truncation mutations associated with arCC, and the blue arrow shows the missense mutation p.Leu1376Pro.

(B) Amino acid sequence alignment around the FYCO1 Leu1376 amino acid (asterisk) in eight species, ranging from humans to zebrafish.

A single missense mutation, Leu1376Pro, was observed in two families, 060031 and 060058. Occurrence in two unrelated families, segregation with the disease in these two families, and absence in ethnically matched control samples strongly suggests that p.Leu1376Pro might be causative rather than a benign variant. The p.Leu1376Pro missense mutation disrupts a residue conserved from humans to mouse (L1376) within the GOLD domain, suggesting that it is critical for protein function (Figure 4B). In addition, L1376 is conserved in various mammalian species as divergent as cows, dogs, mice, rabbits, and marmosets and shows only conservative changes to isoleucine and valine in platypuses and zebrafish, respectively (Figure 4B). The p.Leu1376Pro change was scored (1.79) as “possibly damaging” for protein function with PolyPhen and as “not tolerated” by SIFT algorithms. Also, the Blosum80 matrix score for this amino acid change indicates that it is potentially damaging for protein function. However, final confirmation of the causative role of this mutation awaits functional assays.

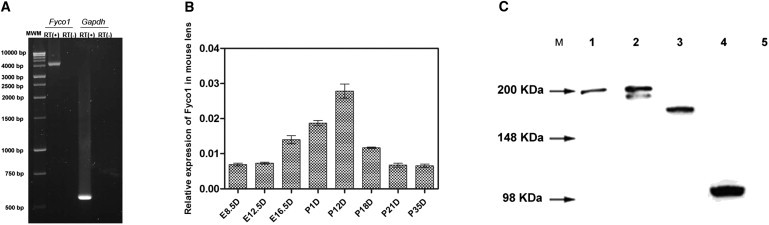

FYCO1 is reported to be widely expressed, especially in heart and skeletal muscle, skin, adipose tissue, and the ovary24 but also in the eye (Unigene). However, the pattern of FYCO1 expression within the eye has not previously been described. To confirm that candidate genes, including Fyco1, are expressed in the lens, RNA was extracted from lenses of wild-type (FVB\N strain) mice at the following stages: E8.5, E12.5, E16.5, P1, P12, P18, P21, and P35. Contamination of dissected lenses with adjacent tissue was estimated to be less than 5% by visual examination. Lens cDNA was made by RT-PCR with the SuperScriptTM III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad), and direct PCR amplification of the cDNA was performed. Expression of Fyco1 was tested by PCR analysis of lens full-length cDNA with the use of one pair of gene-specific primers, which amplify a 4317 bp product. The PCR primers (forward, 5′-ATGGCTTCTAGCAGCACTGAGA-3′; reverse, 5′-CTATGGGAAATCGCTTCCATCG-3′) are located in exons 2 and 18, respectively. PCR Products were then electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The ubiquitously expressed Gapdh was used as an amplification control. No alternative splicing was detected by amplification across adjacent and multiple exons (data not shown).

In order to characterize expression of Fyco1 in the eye lens during development, we assessed levels of Fyco1 transcript expression in the mouse eye lens by quantitative RT-PCR of RNA and generated a 4317 bp product spanning exons 2–18 of the mouse Fyco1 (Figure 5A). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with SYBR Green chemistry in an ABI Prism 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK). The Fyco1 real-time PCR primers were 5′- GCACCAAGAGGCTATGACTTG-3′ and 5′- ACTACTCATGCTGGAGCTTCG-3′, producing a 117 bp PCR amplicon. The Gapdh real-time PCR primers were 5′-GGTCATCCATGACAACTTTGG-3′ and 5′-GGATGCAGGGATGATGTTCT-3′, creating a 145 bp PCR amplicon. Quantitative (q) RT-PCR was performed, and the data were analyzed according to the recommendations of the manufacturer (QIAGEN). We averaged and normalized results by dividing mean values of Fyco1 mRNA by mean values for Gapdh, the endogenous reference gene. Relative quantification analysis was performed with the comparative CT (2−ΔΔCT) method, for which Gapdh was used as an endogenous control gene for PCR normalization concerning the amount of RNA added to the reverse transcription reactions. Standard deviations were calculated from three independent experiments; each real-time PCR reaction was performed four times so that data reproducibility could be assessed. Relative to levels of the internal control Gapdh, FYCO1 mRNA is expressed at E8.5, in the developing lens placode. It remains relatively stable until it doubles between E12.5, at which time the lens vesicle has been formed and the primary lens fibers have elongated from the posterior wall to fill the lens vesicle, and E16.5. During this time the anterior epithelial cells divide and move to the lens equator, where they elongate and differentiate to form the secondary lens fiber cells, whose formation is associated with loss of organelles. Increasing rapidly, FYCO1 expression then roughly doubles between E16.5 and P12 before gradually decreasing to levels similar to those in early embryonic life (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

FYCO1 Expression in the Lens and Human Lens Cell Culture

(A) RT-PCR amplification of Fyco1 mRNA from P3W mouse eye lens. RT (+) and RT (–) denote controls with or without reverse transcription, respectively. Lane 1, full-length Fyco1 transcript; lane 2, negative control for Fyco1 transcript; lane 3, Gapdh transcript; lane 4, negative control for Gapdh transcript. MWM stands for molecular-weight marker.

(B) Relative expression of Fyco1 in mouse eye lens tissues at various ages. Expression of Fyco1 was measured in lens tissues by qRT-PCR at different time points during aging. Data represent the mean (±SD) on an arbitrary scale (y axis) representing expression relative to the housekeeping gene Gapdh.

(C) Characterization of mutant and wild-type GFP-FYCO1 by immunoblot analysis. Lane 1, transfected wild-type FYCO1-GFP lysate; lane 2, lysate transfected with mutant FYCO1-GFP (p.Leu1376Pro); lane 3, lysate transfected with mutant FYCO1-GFP (p.Leu1288TrpfsX37); lane 4, lysate transfected with mutant FYCO1-GFP (p.Gln736X); lane 5, untransfected lysate. “M” indicates molecular-weight positions of the SeeBlue2 Plus molecular-weight marker. Wild-type proteins migrate at the predicted molecular weight of 197 kDa. Missense mutant proteins migrate at the predicted molecular weight of 197 kDa. Duplication mutant proteins migrate at the predicted molecular weight of 165 kDa. Nonsense mutant proteins migrate at the predicted molecular weight of 105 kDa.

Wild-type and mutant human FYCO1-GFP fusion proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting after transient transfection of human lens epithelial cells with wild-type and mutant FYCO1-GFP constructs. The cDNA encoding the full-length wild-type FYCO1 was purchased from Origene (ORF Clones). Full-length wild-type FYCO1 cDNA was cloned into the phCMV6-AC-GFP vector, and a GFP tag was placed at the C-terminal end of the cDNA. Single point mutations were introduced into human FYCO1 with a QuickChangeTM site directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). DNA sequences were verified by sequencing. The cells were harvested 48 hr after transfection. Washed cells were lysed with RIPA buffer. Immunoblot analysis was performed with 10 μg reduced proteins separated on 10% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen). Wild-type and L1376P missense mutant GFP-FYCO1 proteins migrate with an approximate molecular weight of 197 kDa (Figure 5C), consistent with the expected molecular mass, although the doublet below the 197 kDa band in the L1376P mutant transfected lanes might represent a degradation product. Characterization of the mutant proteins, p.Leu1288TrpfsX37 and p.Gln736X, with sizes of 165 and 105 kDa, indicated that they were truncated as predicted, (Figure 5C).

In order to localize normal and mutant human FYCO1 protein within the cell, we transfected cultured human lens epithelial cells with pCMV6-AC-FYCO1-GFP and visualized immunofluorescence with a Zeiss LSM 510 laser scanning confocal microscope. Human lens epithelial cells (FHL12428) were cultured in DMEM, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. They were transfected in triplicate in four-well chamber slides (Glass Chamber Slide System) with the full-length wild-type or mutant FYCO1 constructs (plasmid pCMV6-AC-FYCO1-GFP) via PolyJet (SignaGen Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were analyzed 12 hr post-transfection. They were cultured in four-well chamber slides for 12 hr incubation and then fixed in freshly prepared 4% formaldehyde for 20 min, washed twice with PBS, and incubated in blocking buffer (0.5% Tween-20, 1% bovine serum albumin, and 1% goat serum in 1× PBS) overnight in 4°C. The blocking buffer was removed, and cells were incubated with primary antibodies: mouse monoclonal anti-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich), mouse monoclonal anti-golgin 97 (Invitrogen), and polyclonal rabbit anti-LC3antibody (Thermo Scientific Pierce Antibodies) diluted 1:2000, 1:50, and 1:100, respectively, in blocking buffer for 1 hr at room temperature. After being washed three times with PBS plus 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST), cells were incubated for 1 hr at room temperature with a second antibody, either Alexa Fluor 555 goat-anti rabbit IgG or goat-anti mouse IgG (red) diluted in buffer (0.05% Tween-20, 1% bovine serum albumin in 1× PBS). LysoTracker Red DND-99 antibody (Invitrogen, USA, 1:20000) was incubated with live transfected cells for 20 min according to the manufacturer's instructions. After being washed twice with PBS, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Finally, they were washed three times and covered with Gel-Mount and a coverslip. Immunofluorescence was visualized with a Zeiss LSM 700 laser scanning confocal microscope.

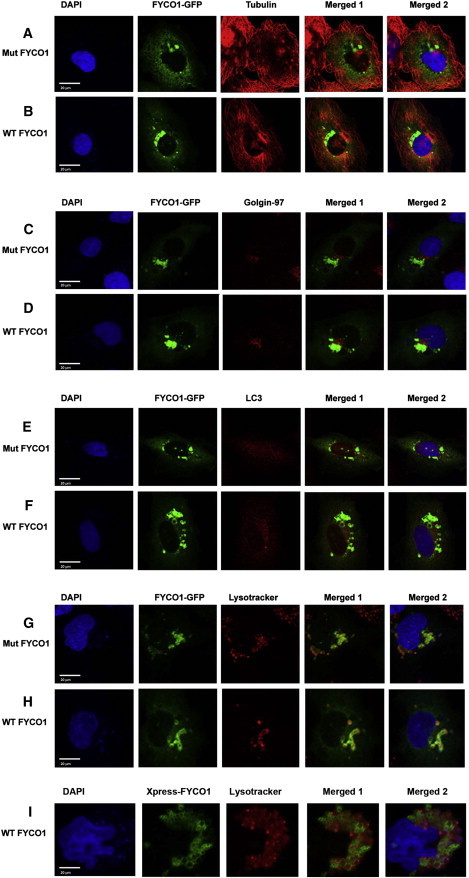

Neither the wild-type nor mutant human FYCO1 colocalizes with tubulin, a microtubule marker (Figures 6A and 6B). The heaviest concentration localizes adjacent to the trans-Golgi compartment, as identified by golgin 97 (Figures 6C and 6D). There is faint colocalization with LC3, a marker for autophagosomes (Figures 6E and 6F) and heavy staining colocalizing with LysoTracker, a marker for endosomes and lysosomes (Figures 6G and 6H). Interestingly, although LysoTracker appears to stain the lysosomes homogeneously, FYCO1-GFP appears to be localized to the outer membranes of the lysosomes and to surround the LysoTracker stained body in a circle, consistent with the results of Pankiv et al.29 This suggests that FYCO1 localizes to the autophagosomes, endosomes, and lysosomes and also suggests that the p.L1376P mutation does not affect localization of FYCO1. To ensure that localization of FYCO1-GFP was not affected by the proximity of the GFP tag to the GOLD domain, we cloned wild-type FYCO1 into into pcDNA4/HisMax C between Kpn1 and Not1, which has an Xpress tag before the FYCO1 sequence, expressed it in human lens epithelial cells, and detected it as above. Localization of the Xpress-tagged FYCO1 was similar to that of the GFP-tagged protein, although there might be a more even distribution of lysosomal staining (Figure 6I).

Figure 6.

Immunofluorescence Images Showing Localization of Mutant and Wild-Type GFP-FYCO1 Proteins in Human Lens Epithelial Cells

Human lens epithelial cells were transfected with pCMV6-AC-FYCO1-GFP in which wild-type (B, D, F, and H) or p.Leu1376Pro mutant FYCO1 (A, C, E, and G) is fused in frame with GFP. Cells were immunostained with organelle-specific antibodies or dyes, including anti-tubulin (red, microtubules) (A and B), anti-golgin 97 (red, Golgi) (C and D), anti-LC3 (red, autophagosomes) (E and F), and LysoTracker Red DND-99 dye (red, endosomes and lysosomes) (G and H). All cells were stained with the nuclear marker DAPI (4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, blue, nucleus). R + G represents overlay of red and green channels. R + G + B depicts red, green, and blue (DAPI) channels. Scale bars represent 20 μm. Both wild-type (WT) and mutant (Mut) proteins partially colocalize adjacent to Golgi, autophagosomes, endosomes, and lysosomes of the cytoplasm of human lens epithelial cells. Wild-type Xpress-tagged FYCO1 shows similar localization (I).

The CATC2 locus was first mapped to chromosome 3 in 2001 by Pras et al.,19 but the disease-associated variant had not been identified. In this study, arCC in twelve unrelated Pakistani families has been mapped to a 3.5 cM (12 Mb) chromosomal region, 3p21, flanked by D3S3685 and D3S1289, which overlaps with the CATC2 locus described by Pras et al.19 arCC in these families and in family 1 from Pras et al.19 has been associated with mutations in FYCO1, the gene encoding a protein important for transport of autophagocytic vesicles. In total, nine different FYCO1 mutations were identified in 13 (12 Pakistani and one Arab Israeli) arCC families including 44 affected individuals, in all of which the disease segregates with the mutant allele. As part of an ongoing collaboration to study arCC in Pakistan, we have studied 125 familial cases of arCC, and FYCO1 is responsible for approximately 10% to the total genetic load of congenital cataracts in our study, and possibly in the Pakistani population as well, which would mean that FYCO1 mutations are among the most common causes of inherited congenital cataracts in the Pakistani population as a whole. In addition, identification of a FYCO1 mutation in an Arab Israeli family indicates that disruption of this gene is a cause of arCC in additional populations as well. This will be further clarified as FYCO1 is screened in other populations.

Autophagy is associated with a variety of disease processes, including tumorigenesis, neurodegenerative diseases, cardiomyopathy, Crohn disease, fatty liver, type II diabetes, defense against intracellular pathogens, antigen-presentation, and longevity.30–33 Among the proteins and multimolecular complexes that contribute to autophagosome formation are PI(3)-binding proteins, PI3-phosphatases, Rabs, the Atg1/ULK1 protein-kinase complex, the Vps34-Atg6/beclin1 class III PI3-kinase complex, and the Atg12 and Atg8/LC3 conjugation systems. Soon after an autophagosome forms, its outer membrane fuses with lysosomes to form autolysosomes, a process requiring Rab7.34,35 FYCO1 was independently identified as a Rab7 effector and a PI(3)P-binding protein and was found to associate with the exterior of autophagosomes via its FYVE domain. Pankiv et al. have recently reported that depletion of FYCO1 leads to perinuclear accumulation of residual autophagosomes, and proposed a role for FYCO1 in tethering autophagosomes to plus-end-directed microtubule motor proteins to explain this phenotype. FYCO1 also interacts preferentially with GTP-bound Rab7, the GTPase implicated in autophagosome-lysosomal fusion, and Rab7 recruits FYCO1 to autophagosomes.29,36 This suggests that FYCO1 mediates microtubule plus-end-directed movement of autophagosomes. In transfected human lens epithelial cells, FYCO1 proteins localize to lysosomes and autophagosomes, particularly near the Golgi complex in the perinuclear area (Figure 6). Behrends et al. found that FYCO1 associates with two microtubule motor proteins, kinesin (KIF) 5B and KIF23.37 Interestingly, depletion of KIF5B leads to perinuclear accumulation of autophagosomes, allowing Behrends et al. to propose that KIF5B links FYCO1-positive autophagosomes to microtubules to maintain cortical localization.38 Behrends et al. also showed that C7orf28A associates with FYCO1. C7orf28A depletion led to an increase in autophagosome number without blocking autophagosomal flux.37 Thus, FYCO1 seems to function as a platform for assembly of vesicle fusion and trafficking factors.

The high frequency of frameshift, splice, and nonsense mutations and the recessive inheritance pattern seen in the families suggest that arCC in these families results from loss of FYCO1 function. Loss of functional FYCO1 could lead to arCC through a variety of mechanisms. Autophagy is important for degradation of aggregated misfolded proteins, and accumulation of protein aggregates is a classic mechanism for light scattering and loss of lens transparency. It is also possible that loss of FYCO1 inhibits transport of autophagosomes from the perinuclear area to the periphery and leads to an accumulation of large numbers of vesicles and hence loss of transparency. Perhaps most intriguing is the possibility that loss of FYCO1 activity inhibits the organelle degradation that is an integral part of differentiation of epithelial cells into lens fiber cells. This would help to explain the specific effect of the absence of functional FYCO1 on the lens even though it is widely expressed in the body. In any event, identification of FYCO1 as a cause of congenital cataracts suggests that autophagy is critically important for lens transparency.

In summary, we report localization of an arCC locus in 12 families of Pakistani origin and one Arab Israeli family to a 3.5 cM (12 Mb) chromosomal region, 3p21-p22, and identification of pathogenic mutations in FYCO1, which has been shown to affect intracellular transport of autophagocytic vesicles. This study provides a new cellular and molecular entry point for understanding lens transparency and human cataracts and because of the frequency of FYCO1 mutations in the Pakistani population might be useful in genetic diagnosis and eventually better cataract treatment or prevention.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to all the family members for their participation in this study and to James Friedman for advice and assistance with the fluorescent localization studies. This study was supported in part by the Higher Education Commission and Ministry of Science and Technology, Islamabad, Pakistan. This work was also supported by the NIH grant ey13022, National Academy of Sciences, and the U.S. Department of State, Washington, DC, USA (Note: All findings and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences or the U.S. Department of State).

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

GeneCards http://www.genecards.org/

Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation, http://www.marshfieldclinic.org/research/pages/index.aspx

Multiple Sequence Alignment Program, http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2/index.html

NCBI UniGene http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/unigene/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.omim.org

PolyPhen program, http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph/

Primer3 program, http://primer3.sourceforge.net/

Splice Site Score Calculation, http://rulai.cshl.edu/new_alt_exon_db2/HTML/score.html

UCSC Genome Bioinformatics, http://genome.ucsc.edu

Reference

- 1.Robinson G.C., Jan J.E., Kinnis C. Congenital ocular blindness in children, 1945 to 1984. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1987;141:1321–1324. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1987.04460120087041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hejtmancik J.F. Congenital cataracts and their molecular genetics. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2008;19:134–149. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lambert S.R., Drack A.V. Infantile cataracts. Surv. Ophthalmol. 1996;40:427–458. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(96)82011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foster A. Cataract—A global perspective: output, outcome and outlay. Eye (Lond.) 1999;13(Pt 3b):449–453. doi: 10.1038/eye.1999.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.François J. Genetics of cataract. Ophthalmologica. 1982;184:61–71. doi: 10.1159/000309186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haargaard B., Wohlfahrt J., Fledelius H.C., Rosenberg T., Melbye M. A nationwide Danish study of 1027 cases of congenital/infantile cataracts: etiological and clinical classifications. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:2292–2298. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merin S. Inherited Cataracts. In: Merin S., editor. Inherited Eye Diseases. Marcel Dekker,Inc.; New York: 1991. pp. 86–120. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiels A., Bennett T.M., Hejtmancik J.F. Cat-Map: Putting cataract on the map. Mol. Vis. 2010;16:2007–2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen D., Bar-Yosef U., Levy J., Gradstein L., Belfair N., Ofir R., Joshua S., Lifshitz T., Carmi R., Birk O.S. Homozygous CRYBB1 deletion mutation underlies autosomal recessive congenital cataract. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007;48:2208–2213. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaul H., Riazuddin S.A., Shahid M., Kousar S., Butt N.H., Zafar A.U., Khan S.N., Husnain T., Akram J., Hejtmancik J.F., Riazuddin S. Autosomal recessive congenital cataract linked to EPHA2 in a consanguineous Pakistani family. Mol. Vis. 2010;16:511–517. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ponnam S.P., Ramesha K., Tejwani S., Ramamurthy B., Kannabiran C. Mutation of the gap junction protein alpha 8 (GJA8) gene causes autosomal recessive cataract. J. Med. Genet. 2007;44:e85. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.050138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ponnam S.P., Ramesha K., Tejwani S., Matalia J., Kannabiran C. A missense mutation in LIM2 causes autosomal recessive congenital cataract. Mol. Vis. 2008;14:1204–1208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pras E., Frydman M., Levy-Nissenbaum E., Bakhan T., Raz J., Assia E.I., Goldman B., Pras E. A nonsense mutation (W9X) in CRYAA causes autosomal recessive cataract in an inbred Jewish Persian family. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41:3511–3515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pras E., Levy-Nissenbaum E., Bakhan T., Lahat H., Assia E., Geffen-Carmi N., Frydman M., Goldman B., Pras E. A missense mutation in the LIM2 gene is associated with autosomal recessive presenile cataract in an inbred Iraqi Jewish family. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:1363–1367. doi: 10.1086/340318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pras E., Raz J., Yahalom V., Frydman M., Garzozi H.J., Pras E., Hejtmancik J.F. A nonsense mutation in the glucosaminyl (N-acetyl) transferase 2 gene (GCNT2): Association with autosomal recessive congenital cataracts. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45:1940–1945. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramachandran R.D., Perumalsamy V., Hejtmancik J.F. Autosomal recessive juvenile onset cataract associated with mutation in BFSP1. Hum. Genet. 2007;121:475–482. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0319-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riazuddin S.A., Yasmeen A., Yao W., Sergeev Y.V., Zhang Q., Zulfiqar F., Riaz A., Riazuddin S., Hejtmancik J.F. Mutations in betaB3-crystallin associated with autosomal recessive cataract in two Pakistani families. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005;46:2100–2106. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smaoui N., Beltaief O., BenHamed S., M'Rad R., Maazoul F., Ouertani A., Chaabouni H., Hejtmancik J.F. A homozygous splice mutation in the HSF4 gene is associated with an autosomal recessive congenital cataract. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45:2716–2721. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pras E., Pras E., Bakhan T., Levy-Nissenbaum E., Lahat H., Assia E.I., Garzozi H.J., Kastner D.L., Goldman B., Frydman M. A gene causing autosomal recessive cataract maps to the short arm of chromosome 3. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2001;3:559–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grimberg J., Nawoschik S., Belluscio L., McKee R., Turck A., Eisenberg A. A simple and efficient non-organic procedure for the isolation of genomic DNA from blood. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:8390. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.20.8390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cottingham R.W., Jr., Idury R.M., Schäffer A.A. Faster sequential genetic linkage computations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1993;53:252–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lathrop G.M., Lalouel J.M. Easy calculations of lod scores and genetic risks on small computers. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1984;36:460–465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiss H., Darai E., Kiss C., Kost-Alimova M., Klein G., Dumanski J.P., Imreh S. Comparative human/murine sequence analysis of the common eliminated region 1 from human 3p21.3. Mamm. Genome. 2002;13:646–655. doi: 10.1007/s00335-002-3037-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiss H., Yang Y., Kiss C., Andersson K., Klein G., Imreh S., Dumanski J.P. The transcriptional map of the common eliminated region 1 (C3CER1) in 3p21.3. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;10:52–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marchler-Bauer A., Anderson J.B., Chitsaz F., Derbyshire M.K., DeWeese-Scott C., Fong J.H., Geer L.Y., Geer R.C., Gonzales N.R., Gwadz M. CDD: specific functional annotation with the Conserved Domain Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D205–D210. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lupas A., Van D.M., Stock J. Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science. 1991;252:1162–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rose A., Schraegle S.J., Stahlberg E.A., Meier I. Coiled-coil protein composition of 22 proteomes—Differences and common themes in subcellular infrastructure and traffic control. BMC Evol. Biol. 2005;5:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wormstone I.M., Tamiya S., Marcantonio J.M., Reddan J.R. Hepatocyte growth factor function and c-Met expression in human lens epithelial cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41:4216–4222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pankiv S., Alemu E.A., Brech A., Bruun J.A., Lamark T., Overvatn A., Bjørkøy G., Johansen T. FYCO1 is a Rab7 effector that binds to LC3 and PI3P to mediate microtubule plus end-directed vesicle transport. J. Cell Biol. 2010;188:253–269. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200907015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eskelinen E.L., Saftig P. Autophagy: A lysosomal degradation pathway with a central role in health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1793:664–673. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levine B., Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mizushima N., Levine B., Cuervo A.M., Klionsky D.J. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Münz C. Enhancing immunity through autophagy. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2009;27:423–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gutierrez M.G., Munafó D.B., Berón W., Colombo M.I. Rab7 is required for the normal progression of the autophagic pathway in mammalian cells. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:2687–2697. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jäger S., Bucci C., Tanida I., Ueno T., Kominami E., Saftig P., Eskelinen E.L. Role for Rab7 in maturation of late autophagic vacuoles. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:4837–4848. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pankiv S., Johansen T. FYCO1: Linking autophagosomes to microtubule plus end-directing molecular motors. Autophagy. 2010;6:550–552. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.4.11670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Behrends C., Sowa M.E., Gygi S.P., Harper J.W. Network organization of the human autophagy system. Nature. 2010;466:68–76. doi: 10.1038/nature09204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cardoso C.M., Groth-Pedersen L., Høyer-Hansen M., Kirkegaard T., Corcelle E., Andersen J.S., Jäättelä M., Nylandsted J. Depletion of kinesin 5B affects lysosomal distribution and stability and induces peri-nuclear accumulation of autophagosomes in cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.